Abstract

This chapter is based on 90 individual semi-structured interviews asking students about their experiences of assessment for learning in five disciplines: architecture, business, geology, history and law. Four features of assessment valued by students are discussed: assessment mirroring real-life uses of the discipline, flexibility and choice, developing understanding of expectations and productive feedback processes. A striking finding was student cynicism about rubrics or lists of criteria in contrast to their enthusiasm for exposure to exemplars of previous student work. Two challenging modes of assessment are also focal points for analysis: the assessment of participation and group assessment. Assessed participation through verbal and written means was perceived quite positively by student informants. Group assessment attracted mixed student views and might be enhanced by feedback processes involving interim reports of progress to discourage procrastination and free-riding. The chapter concludes with some discussion of how the analysis of exemplars and productive feedback designs could be scaled up and further investigated.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Assessment for learning (AfL) aims to change assessment from something done to students to something done with, and for, them (Brown & Knight, 1994). A repercussion of this goal is that it is vital to investigate students’ perceptions of assessment. There is quite a lot known about the student experience of assessment, but the topic remains relatively sketchily explored, although for an exception, see Jessop (this volume, Chap. 4). It is a trend in the UK National Student Survey, for example, that students perceive concerns about how assessment and feedback are handled (Williams & Kane, 2009), but such relatively broad-brush treatments do not provide much detail of the student reaction to assessment. The aim of this chapter is to investigate how students perceive key aspects of their assessment experience. Understanding the student response is a facilitating factor for the scaling up of AfL because the student perspective lies at its heart.

My recent research investigated the assessment practices of five teacher recipients of awards for excellence. In the book treatment of that research, student perceptions were triangulated with teacher interviews and classroom observational data and weaved within narratives of the courses (Carless, 2015a). In this chapter, I want to bring together students’ responses in a more focused way to analyse their perceptions of the assessment processes which they experienced in the modules under investigation.

Literature Review: Students’ Perspectives on Assessment

Rather than attempting a more wide-ranging review of literature, for the purposes of this chapter, I discuss selected literature which speaks to the issues to be discussed in the Findings. The rationale for this strategy is to provide a coherent treatment of key issues raised by student informants.

The existing knowledge base on students’ responses to assessment suggests a number of themes. Students seem to welcome alternative assessment when it seems fair and relates to real-life application of disciplinary knowledge (McDowell & Sambell, 1999). Students are sometimes reported to be unreceptive to innovative assessment but may also relish some variety compared to what they have done before (Carless & Zhou, 2015). Students’ response to assessment emanates from the totality of their previous experiences of learning and being assessed (Boud, 1995). Accordingly, it is students’ perceptions rather than the actual features of assessment tasks which have most impact on how they respond to assignments (Lizzio & Wilson, 2013).

Students seem to favour assessment designs which involve some choice for them to tailor assignments to their preferences or capabilities (Bevitt, 2015; Lizzio & Wilson, 2013). Personal interest in the task improves performance and enhances persistence in the face of adversity (O’Keefe & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014). Choice also seems to encourage students to adopt deep approaches to learning (Craddock & Mathias, 2009), whereas lack of autonomy may increase anxiety and use of surface learning strategies (Coutts, Gilleard, & Baglin, 2011).

Students are more likely to have positive perceptions of assessment tasks when it is clear what is required. Rubrics bring much-needed transparency to the assessment process, and there is potential for positive impacts on student learning (Jonsson and Panadero, this volume). On-display assignments in which student work is openly visible rather than being private are a useful means of indicating how rubrics are operationalized (Hounsell, McCune, Hounsell, & Litjens, 2008). Exemplars of student work are a further means of illustrating how quality is achieved, and there is plenty of evidence that students are positive about being exposed to exemplars (Hendry, Armstrong, & Bromberger, 2012; Lipnevich, McCallen, Miles, & Smith, 2014). A concern discouraging teachers from using exemplars is that some students may interpret them as model answers to be imitated, and this may reduce student creativity or lead to formulaic unimaginative work (Handley & Williams, 2011). The sensitive handling of the teacher-led discussion phase about the exemplars may be a means of reducing this problem by unpacking the nature of quality work (To & Carless, 2015).

Students’ concerns about the value and usefulness of feedback processes in higher education have been well-rehearsed over the last 15 years or so. For many students, end-of-course comments often seem like a perversely belated revelation of things that should have been made clear earlier (Crook, Gross, & Dymott, 2006). A key strategy to tackle this issue of timeliness is to embed integrated cycles of guidance and feedback within the learning activities for a course (Hounsell et al., 2008). A related line of thinking involves repositioning feedback as a fundamental component of curriculum design rather than a marking and grading routine through which information is delivered by teachers to learners (Boud & Molloy, 2013).

Group assessment is a mode of alternative assessment which often provokes negative reactions amongst students (Flint & Johnson, 2011). Students seem to find it difficult to work effectively in groups and are concerned that assessed group work may negatively impact on their overall grades (Pauli, Mohiyeddini, Bray, Michie, & Street, 2008). Group work is often perceived as unfair because of the free-riding phenomenon (e.g. Davies, 2009). Students may not tackle group work together, instead dividing up the tasks and doing them individually (Brown & McIlroy, 2011). This works against a powerful rationale for working in teams in that the more complex learning is, the less likely that it can be accomplished in isolation from others (Boud, 2000). Students with negative experiences of group assignments express a need for more teacher involvement to support group processes (Volet & Mansfield, 2006).

Another potentially controversial mode of assessment is assessing participation. This should not imply grades being awarded for attendance but could be worthwhile if it involves well-defined intellectual contributions to the course. Assessment of student participation may engender various benefits in terms of student preparation prior to class, development of oral communication skills and regular engagement and involvement (Armstrong & Boud, 1983). Students seem to appreciate course material more when participation is demanded but at the same time report being less likely to enrol in such courses because of the anxiety it provokes (Frisby, Weber, & Beckner, 2014). Probably the biggest challenge for the assessment of participation is that students often have limited understanding of how their participation grade is determined due to its subjectivity and somewhat ill-defined nature (Mello, 2010).

Method

The basis for this chapter is 90 individual semi-structured interviews with 54 undergraduate students at the University of Hong Kong, an English-medium research-intensive university. Some students were interviewed more than once, and they came from the disciplines of architecture, business, geology, history and law. Thirty-nine of the student informants were Hong Kong Chinese, 11 were mainland Chinese, 3 European (all studying business) and 1 South Asian (studying architecture).

Students were interviewed individually for about 30–45 min to ascertain their perceptions of different key issues which related to their experiences in the courses being researched. Aspects investigated were wide-ranging, including students’ perceptions of the assessment tasks in the course, their views about rubrics and exemplars, their opinions of feedback processes and other relevant course-specific issues. Not all of these issues were covered within a single interview because the aim was to elicit students’ views which most resonated with their immediate assessment experiences.

The analysis involves the interpretation of a large corpus of student interviews. In view of the inevitable difficulty of selecting representative student quotations and to avoid repeating quotations appearing in Carless (2015a), I have decided to adopt a somewhat unusual procedure. In what follows, I summarize rather than quote what the students said. Despite limitations that this entails, my hope is that the student views emerge whilst also saving space for bringing out commentary, inferences and implications.

Findings

Students carried out four of the most common modes of assessment in contemporary higher education: examinations; written assignments, such as essays or reports; oral presentations; and group projects. There were also a variety of other tasks. In architecture, students were assessed on a portfolio of designs which they had developed during the semester. In law, students curated over time an analysis of legal cases reported in the local media through a ‘reflective media diary’: an assessment task which combined elements of traditional portfolio and e-portfolio. In business and history, students were assessed on participation comprising both written and verbal participation elements. There were also some discipline-specific assessment tasks. In geology, students carried out laboratory reports on features of rocks which also rehearsed some of the skills needed in the subsequent examination. In law, there was an option of a ‘photo essay’ whereby students photographed a potential tort law issue from daily life and wrote a short legal analysis. In history, students could choose between a fieldwork report on a museum visit and a ‘scavenger hunt’: an Internet-based simulation involving visiting sites of historical significance and scavenging for clues.

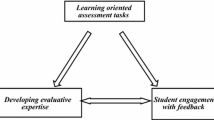

First, I discuss students’ perceptions of four key task features which were centrally evident in the data: assessment mirroring real-life uses of the discipline, flexibility and choice, understanding expectations and productive feedback processes. These relate to the AfL strategies of productive task design, developing student understanding of quality and effective feedback processes (Carless, this volume, Chap. 1,). Second, I focus on two specific challenging modes of assessment: assessing participation and group assessment because from a student perspective, they are at the same time potentially worthwhile, yet often problematic.

Assessment Mirroring Real-Life Uses of the Discipline

Students reacted enthusiastically to assessments which bore a relevance to real-world applications of the discipline. For example, law students made a number of positive comments about the assignments which were related to how law was practised in daily life. These included their reflective media diary about legal cases reported in the media as well as an assessed report of a self-organized visit to a labour tribunal. Their main reservation was the time-consuming nature of some of these activities, particularly if the amount of assessment weighting was relatively low.

History students appreciated the fieldwork report on their museum visit because it helped them to understand how museums are arranged to highlight certain messages and downplay others. The scavenger hunt drew more mixed reactions from students in that for many of them, it was difficult for them to understand and appreciate. Those who participated in it did, however, report finding it rewarding. A related issue was that a wide variety of tasks, including some innovative ones, could be confusing to students, particularly those who are less committed or less able.

In architecture, students expressed appreciation of a number of elements which related to real-life applications of their discipline. Their work was contextualized around the design of houses for a mainland Chinese village a few hours away from the university which underscored the real-life nature of architectural design. Students also compared the processes of developing a design portfolio for assessment with how professional architects work. One of the students viewed his portfolio as representing how designs became real in that the portfolio is a kind of publication which synthesizes ideas. Another student emphasized the importance in a student’s portfolio of showing the procedures used to arrive at the solution in contrast with the professional architect who is more focused on displaying various perspectives. The iterative process of developing designs, presenting them publically for critical review, receiving feedback and then revising was also seen by students as mirroring the way architecture operates in real life.

Flexibility and Choice

Students reported valuing assessments which involved some flexibility and choice. For example, in the history case, students had different options both in relation to the tasks and how they could be approached. For their individual project, they could choose from a long list of possible topics or suggest one of their own (see also Carless, 2015a, Chap. 4). Students could produce conventional written assignments or more innovative ones, such as videos or podcasts. A recurrent theme in the student data was the term ‘flexibility’ which students viewed as offering the chance to work on something which had a personal meaning for them and also provided them with opportunities to produce their best performance or avoid tasks with which they are unfamiliar. Choice also facilitates learner autonomy which a number of students favoured.

In law, there was some choice of assessment tasks and also some flexibility in terms of weighting of assessment. For example, students who were less confident about their exam performance could reduce the exam weighting from 60 to 40 % by doing alternative tasks, such as a research essay. The idea of choice enabling students to diversify risk was particularly attractive to them. A number of students, however, expressed concerns about workload. On the one hand, the coursework options were attractive and a positive learning experience, whereas on the other hand, the processes engendered considerably more overall workload than those courses assessed entirely through examinations.

Although students expressed a wide range of positive views about choice and flexibility, there are some potential disadvantages of choice. Students may need some guidance on what kinds of choice are available and how they relate to the bigger picture of the learning outcomes they are trying to develop. Students might choose easy options, such as something similar to what they have done before. Even worse, there may be concerns that providing choice might make cheating or plagiarism easier.

Developing Understanding of Expectations

Students need to understand the goals of assessment tasks and the standards expected. In all the courses I observed, teachers provided details at the outset of assessment requirements and associated criteria in the form of rubrics. Somewhat to my surprise, the majority of students, reported a rather cynical view of rubrics or lists of criteria, using adjectives, such as ‘vague’, ‘unclear’, ‘all the same’ and ‘inert’ to describe them. Students also commented that they were not convinced that the criteria shown to them fully represented how teachers evaluated student work. Teachers’ impressions and personal judgments were deemed by students to be more significant than what was stated in the criteria: a point also made in the literature (Bloxham, Boyd, & Orr, 2011).

Instead, students particularly valued exposure to exemplars which could help them understand what teachers were looking for in a particular assessment task. Students perceived that exemplars are more effective than rubrics at indicating how assessment requirements are operationalized. They reported them as being valuable in indicating what was required and also as a useful benchmark of the academic standards. Students felt this was particularly necessary in relation to innovative tasks with which they are not familiar. These unfamiliar formats provide a sense of anxiety as students are not sure how to obtain a high grade, and exemplars can relieve some of these concerns.

Students were asked how they used exemplars to inform their own assignments and there were a variety of responses. Some students reported using the exemplars to help them understand the abstract assessment criteria in more concrete terms. Other students stated that they could obtain some ideas and inspiration from the exemplars. Students also reported using exemplars as a template for their own work, for example, by imitating the format and then adding some ideas of their own. Overall students were highly positive about being exposed to exemplars and expressed a wish that more teachers would make this a regular part of their practice.

Productive Feedback Processes

Students frequently expressed the view that they wanted to receive feedback during the process of their work so that they could act on it in a timely way for the teacher who had provided it. Timeliness was thus a key issue from their point of view. They did not perceive much scope for transferring end of module feedback from one course to another: they might not remember feedback; assignment formats and content varied; and they believed that different teachers had different requirements.

There were some feedback design elements in the case studies (see also Carless, 2015a, Chap. 11). In architecture, students presented their design work in progress for ‘critical review’. These processes provided individual feedback for the presenter and also acted as ‘on-display’ assignments which could facilitate wider discussion of architectural issues. Particularly fruitful from the student perspective was the final review when all the student designs were displayed in the studio, and there were ample opportunities for peer feedback, comparison and discussion.

In the history case, a feedback design feature was that for their individual project, the teacher required a draft worth 10 % and final version worth a further 30 %. This was generally popular with students as it provided timely feedback which students could act on. Two drawbacks also emerged. First, there is a danger that feedback on drafts can create student dependency on the teacher and fail to develop self-evaluative capacities. Second, when feedback on a draft does not connect or is misunderstood, this can lead to frustrations: a particular issue for lower-achieving students.

In the business case study, a prominent feedback element was in-class dialogues facilitated by a small class size (see also Carless, 2013a). Students spoke positively of the teacher’s skill in creating an interactive classroom with plentiful verbal feedback which challenged them to raise their thinking to a higher level. The amount of classroom time devoted to interaction also represented some tensions: some students would have preferred more content to be delivered; other students felt that discussions were sometimes tangential to core course content.

A useful feedback design feature in geology was early interaction around student topics for their group project which provided students with timely guidance that they were on the right track. For feedback on the oral presentation for the group project, students perceived some inconsistencies in standards between the different teachers. They generally seemed to prefer the more easy-going encouraging feedback of some tutors, rather than the more critical but perceptive analyses of others.

In the law case, a special feature was immediate interactive verbal feedback after the exam: students were invited to remain in the exam hall to discuss their answers and this was also supplemented by online discussion. Students expressed appreciation of the opportunity for prompt discussion of their exam performance. For some students, however, receiving immediate feedback about the exam was perceived as anxiety-inducing so they preferred not to join the discussion in case it revealed discouraging failings in their performance (Carless, 2015b).

Assessing Participation

Assessing participation was a significant feature of the business and history case studies. Both of these cases involved both oral and written participation: in business, verbal in class and written through a blog, and in history, small-group tutorial participation and written assessment of short in-class responses. The combination of verbal and written involvement represents a positive feature which allows students of different personalities and preferences to participate in alternative ways.

There was an atmosphere in the business case study which was quite different to other university classes I have observed. There was a kind of ‘productive tension’, a feeling that something interesting or provocative might happen and that participants should be well-prepared. The teacher might ask at any point a challenging individual question and may also interrogate the resulting answer. Accordingly, students reported that they were more concentrated and better prepared in this class as opposed to others. This challenging atmosphere was also balanced by warmth, empathy and trust between participants (Carless, 2013b). The participation grade was one of the factors that students reported as encouraging them to maintain their concentration and express their thoughts. They did, however, express the view that they contributed because they wanted to do so and had something to say, not merely to gain marks.

In the history case, an innovative strategy was the weekly assessed written in-class ‘One sentence responses’: concise answers to a question that related to the topic to be addressed in the following session. Students perceived this strategy as being novel and fun and providing a useful entry point to the content of the next session. In the following class, the teacher also carried out some follow-up on the student responses, including displaying examples of good contributions which acted as a form of feedback and clarification of expectations. Overall, the short-written responses seemed to bring a number of benefits as they encouraged student expression of thoughts in a concise form and prompted them to reflect on what was coming next in the course.

Students were generally positive about the impact of assessed participation on their engagement and the classroom atmosphere. Some students even expressed the view that they might not attend class so regularly if participation was not assessed. Students evidenced, however, quite a lot of doubts and confusion as to how participation grades were awarded even though rubrics were made available to them. They generally perceived participation grades as being subjective and hard to judge reliably. As long as the assessment of participation did not count for too high a weighting, students were generally acquiescent of these limitations. A factor supporting their tolerance of assessed participation was their trust in the award-winning teachers.

How does the assessment of participation fare in relation to the four features of assessment valued by students discussed above? There are linkages with real life in that participation in discussion and debates, for example, in meetings, is an important part of the future workplace. The way assessing participation was implemented in the cases also resonates with the concept of choice in that students have some flexibility in devoting more effort to expressing their thoughts verbally or in writing. Clarifying expectations is a challenge because it is difficult to model or exemplify what good participation looks like, and rubrics may fail to do this adequately. Feedback on participation is also challenging and potentially time-consuming but, if carried out effectively, could contribute to clarifying expectations about what good participation entails.

Overall, the assessment of participation seems a somewhat contentious issue in terms of the challenge of reliable assessment of something as potentially vague as participation. What struck me was the positive impact it had on student engagement and classroom atmosphere. Assessing clearly defined contributions, with well-defined criteria, could form part of a worthwhile overall assessment design (Carless, 2015a).

Group Assessment

Group assessment was a core element of both the business and geology cases (see Carless, 2015a, Chap. 6). Here I summarize student perceptions and then conclude with some recommendations. Students expressed mixed reactions and a variety of experiences. Some groups were reported as operating cohesively and a capable coordinator was an important feature of that kind of group. In other teams, the group leader ended up doing most of the work: sometimes they seemed quite happy in that role because they perceived themselves as more capable, more motivated or with a higher intensity of desire for a high grade. On other occasions, there appeared to be simmering resentment at the failure of teammates to attend meetings, respond to electronic communication or produce work in a timely fashion. Procrastination was a regular problem and often resulted in the most responsible team member ending up doing the work left by a free-rider (cf. Davies, 2009).

A key issue is the amount of guidance and support which is offered in relation to the processes of group assessment. In one of the introductory lectures in geology, the teacher explained the guidelines for the group assessment and shared some tips and experiences. He provided guidance on how to narrow down the focus of a topic and spoke about the need for some novelty in what was being investigated with an aim of generating insight. It was evident that some students were not fully concentrated on what the teacher was saying; rather, they were starting to negotiate with classmates on the composition of the groups. At the time, this seemed to me a missed opportunity to pick up on some important cues as to successful execution of the group project. On further reflection from the student perspective, this may be a logical response as the members of your team are a significant factor in completing a group project well and attaining a high grade.

Students perceived a number of benefits accruing from group assessment. These included learning from peers, developing teamwork and interpersonal skills and the social aspects of collaborating with peers. Peer support can provide a sense of safety and the feeling of not being on your own seemed to be particularly reassuring for first year students. In the business class, students generally seemed to relish working in groups. Some of these teams reported spending a lot of time discussing and negotiating and this seemed to be facilitating rich learning experiences.

Relating the assessment of group projects with the previous themes, work in teams mirrors the future workplace. It can involve some flexibility and choice in relation to topics and group membership. There seem to be some challenges for students in understanding expectations, especially in relation to balance between process and product. To what extent are both the processes of working in teams and the final product equally valued and rewarded? A useful strategy to enhance group assessment would be to enhance the integration of guidance and feedback processes. This might involve interim reports of work in progress which could be in the form of online reports or brief in-class progress updates. Requiring students to report on the progress of their projects reduces procrastination, encourages student accountability, discourages free-riding and provides opportunities for timely feedback and guidance, including student self-evaluation.

Discussion

The findings carry some similarities with previous literature and also add some further dimensions. For example, the data reinforce student enthusiasm for assessment mirroring real-life uses of the discipline and reiterate some of the challenges of group assessment. In comparison with these well-worn themes, student choice has been relatively modestly treated in the existing assessment literature. Choice can be a way of providing students with options to cater for their strengths and preferences or perhaps, more fundamentally, a means of generating some student ownership of the assessment process. It is also possible that students may achieve superior outcomes when they have choice because we generally perform better when we possess some form of agency in relation to academic work. The concept of student choice also resonates with emerging recent trends in the development of personalized learning and new technologies where students co-construct their own learning pathways and learning environments.

Relatively few studies have elicited students’ opinions of both rubrics and exemplars. The findings from this study strikingly indicate that students find exemplars more useful than rubrics (cf. Jonsson and Panadero, this volume). Exemplars are perceived as concrete illustrations of how an assignment can be tackled, whereas students perceived rubrics as vague. The findings can be contrasted with Lipnevich et al. (2014) where students welcomed both exposure to exemplars and the rubric, but it was the ‘rubric only’ group who improved more than ‘exemplars only’ or ‘rubric and exemplars’ groups in a quasi-experimental study. Whether and how exemplars support students to develop superior learning outcomes bears further investigation. The data also reinforce previous studies which report student enthusiasm for exemplars (Hendry et al., 2012). Perhaps it is not surprising that students are positive about exemplars because they make the processes of tackling assignments easier and also provide psychological reassurance. Ways in which exemplars can be used to illustrate the nature of quality without reducing student creativity and intellectual challenge require further research.

The findings in relation to feedback processes provide further evidence of key challenges and dilemmas which are also taken up elsewhere in this volume. What is a healthy balance between teacher guidance, peer feedback and the development of student self-evaluative capacities? How might students be enabled to transfer learning from feedback from one task to another or from one course to another? How can timely in-course feedback processes be developed within the structural challenge of assessment mainly coming at ends of semesters? How can feedback be honest and critical without upsetting student emotional equilibrium?

The generally positive student views on the assessment of participation might stimulate further attention to this topic which seems to have been more widely discussed in the North American literature than in analyses from Europe, Asia or Australia. The informants in this study mainly reported that participation grades prompted engagement, encouraged preparation before coming to class and played a role in enlivening classroom atmosphere. An important facilitating feature is for teachers to explain in the course documentation, during the first class meeting, and periodically thereafter, that good participation is not simply attending class or talking a lot, it depends on the quality of the contributions not their quantity (cf. Mello, 2010). A useful feature of the assessment of participation in the study was the use of both assessed verbal participation and assessed written participation: in other words, there was choice in mode of participation which may reduce anxiety and allow students some degree of flexibility.

The use of short in-class written responses in the history case seems to be a useful alternative to other types of personal response tasks, such as contributions posted on learning management systems, blogs or wikis or the use of electronic voting systems. At the first opportunity, I experimented with this form of assessment in my own teaching, also eliciting positive student responses (Carless & Zhou, 2015). Further research into the value of assessing short in-class or online responses could be worthwhile. Specific avenues in relation to Chinese students might involve investigating the extent to which they may benefit from, or appreciate, incentives to participate actively in class and/or whether they may prefer to contribute their thoughts in writing rather than verbally.

A number of key implications for practice are worth summarizing. Effective assessment task design includes the development of participation in the discipline through mirroring real-life elements, permits some degree of student choice and flexibility, raises awareness of quality work through analysing exemplars and promotes various forms of guidance and feedback dialogues with peers and teachers. The scaling up of good practice in AfL could also be enhanced by integration of productive assessment tasks and the development of student understanding of the nature of quality and feedback designs (Carless, 2015b).

Conclusion

This chapter has discussed students’ perspectives on various aspects of their assessment experience. A number of positive student perceptions are reported, including the use of exemplars to clarify expectations and the design of thoughtful feedback processes. As these are both key AfL strategies, I want to conclude by sketching some prospects for wider implementation and suggest some related avenues for further research.

First, there seems to be some lack of teacher appreciation of the value of exemplars in supporting student capacities to make evaluative judgments (Thomson, 2013). Given that exposure to exemplars is popular with students and has a persuasive academic rationale, this state of affairs needs challenging. Teacher concerns about the use of exemplars need to be interrogated and tackled. Larger-scale studies of the use of exemplars going beyond specific individual courses might provide further evidence of their value. The cumulative impact of exemplars on students over the duration of a programme is also worthy of investigation.

Second, effective feedback processes lie at the heart of AfL but are difficult to manage effectively within the structural challenges of modularized systems in which end-loaded assessment predominates. The need for new ways of thinking about feedback has been highlighted in recent literature (Boud & Molloy, 2013) but still has a long way to go to be scaled up (see also Ajjawi et al., this volume, Chap. 9). The development of teacher and student feedback literacy would be a key facilitating factor for more sophisticated approaches to feedback. Research focused on effective feedback designs at scale and the associated development of feedback literacy are sorely needed.

References

Armstrong, M., & Boud, D. (1983). Assessing participation in discussion: An exploration of the issues. Studies in Higher Education, 8(1), 33–44.

Bevitt, S. (2015). Assessment innovation and student experience: A new assessment challenge and call for a multi-perspective approach to assessment research. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(1), 103–119.

Bloxham, S., Boyd, P., & Orr, S. (2011). Mark my words: The role of assessment criteria in UK higher education grading practices. Studies in Higher Education, 36(6), 655–670.

Boud, D. (1995). Assessment and learning: Contradictory or complementary. In P. Knight (Ed.), Assessment and learning in higher education (pp. 35–48). London: Kogan Page.

Boud, D. (2000). Sustainable assessment: Rethinking assessment for the learning society. Studies in Continuing Education, 22(2), 151–167.

Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: The challenge of design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 698–712.

Brown, C., & McIlroy, K. (2011). Group work in healthcare students’ education: What do we think we are doing? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(6), 687–699.

Brown, S., & Knight, P. (1994). Assessing learners in higher education. London: Kogan Page.

Carless, D. (2013a). Sustainable feedback and the development of student self-evaluative capacities. In S. Merry, M. Price, D. Carless, & M. Taras (Eds.), Reconceptualising feedback in higher education: Developing dialogue with students (pp. 113–122). London: Routledge.

Carless, D. (2013b). Trust and its role in facilitating dialogic feedback. In D. Boud & L. Molloy (Eds.), Feedback in higher and professional education: Understanding it and doing it well (pp. 90–103). London: Routledge.

Carless, D. (2015a). Excellence in university assessment: Learning from award-winning practice. London: Routledge.

Carless, D. (2015b). Exploring learning-oriented assessment processes. Higher Education, 69(6), 963–976.

Carless, D., & Zhou, J. (2015). Starting small in assessment change: Short in-class written responses. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1068272.

Coutts, R., Gilleard, W., & Baglin, R. (2011). Evidence for the impact of assessment on mood and motivation in first-year students. Studies in Higher Education, 36(3), 291–300.

Craddock, D., & Mathias, H. (2009). Assessment options in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(2), 127–140.

Crook, C., Gross, H., & Dymott, R. (2006). Assessment relationships in higher education: The tension of process and practice. British Educational Research Journal, 32(1), 95–114.

Davies, W. (2009). Groupwork as a form of assessment: Common problems and recommended solutions. Higher Education, 58, 563–584.

Flint, N., & Johnson, B. (2011). Towards fairer university assessment: Recognizing the concerns of students. London: Routledge.

Frisby, B. N., Weber, K., & Beckner, B. N. (2014). Requiring participation: An instructor strategy to influence student interest and learning. Communication Quarterly, 62(3), 308–322.

Handley, K., & Williams, L. (2011). From copying to learning: Using exemplars to engage students with assessment criteria and feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(1), 95–108.

Hendry, G., Armstrong, S., & Bromberger, N. (2012). Implementing standards-based assessment effectively: Incorporating discussion of exemplars into classroom teaching. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(2), 149–161.

Hounsell, D., McCune, V., Hounsell, J., & Litjens, J. (2008). The quality of guidance and feedback to students. Higher Education Research and Development, 27(1), 55–67.

Lipnevich, A., McCallen, L., Miles, K., & Smith, J. (2014). Mind the gap! Students’ use of exemplars and detailed rubrics as formative assessment. Instructional Science, 42, 539–559.

Lizzio, A., & Wilson, K. (2013). First-year students’ appraisal of assessment tasks: Implications for efficacy, engagement and performance. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(4), 389–406.

McDowell, L., & Sambell, K. (1999). The experience of innovative assessment: Student perspectives. In S. Brown & A. Glasner (Eds.), Assessment matters in higher education (pp. 71–82). Maidenhead, UK: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Mello, J. (2010). The good, the bad and the controversial: The practicalities and pitfalls of the grading of participation. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 14(1), 77–97.

O’Keefe, P., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2014). The role of interest in optimizing performance and self-regulation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 53, 70–78.

Pauli, R., Mohiyeddini, C., Bray, D., Michie, F., & Street, B. (2008). Individual differences in negative group work experiences in collaborative student learning. Educational Psychology, 28(1), 47–58.

Thomson, R. (2013). Implementation of criteria and standards-based assessment: An analysis of first-year learning guides. Higher Education Research and Development, 32(2), 272–286.

To, J., & Carless, D. (2015). Making productive use of exemplars: Peer discussion and teacher guidance for positive transfer of strategies. Journal of Further and Higher Education. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2015.1014317.

Volet, S., & Mansfield, C. (2006). Group work at university: Significance of personal goals in the regulation strategies of students with positive and negative appraisals. Higher Education Research and Development, 25(4), 341–356.

Williams, J., & Kane, D. (2009). Assessment and feedback: Institutional experiences of student feedback, 1996-2007. Higher Education Quarterly, 63(3), 264–286.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Carless, D. (2017). Students’ Experiences of Assessment for Learning. In: Carless, D., Bridges, S., Chan, C., Glofcheski, R. (eds) Scaling up Assessment for Learning in Higher Education. The Enabling Power of Assessment, vol 5. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3045-1_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3045-1_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-3043-7

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-3045-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)