Abstract

This chapter outlines the rationale, techniques, and benefits of using student-led assessment strategies. Students choose their own assessment contexts by identifying a case and finding a set of problems within the case. Students then conduct a literature review of a theory that applies to the case, followed by a report to the organization with recommendations for better practices.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In this book chapter, I will outline the rationale, techniques, and benefits of using student-led assessmentstrategies. In particular, I discuss one such strategy that I have created and implemented called the noodle bar assessment strategy. I have been using this strategy in my courses for several years. To explain the title, noodle bars are Asian-inspired food outlets that allow customers to choose the combination of ingredients they want in their noodles. Such outlets usually have a set of ingredients, such as noodles, sauces, vegetables, and meat (or meat substitutes). While customers are expected to order a dish that combines the broad categories of ingredients, they are also allowed choices within each category. For example, a customer that dislikes rice noodles but still likes the sauce of a Pad Thai (a popular Thai dish), can mix the Pad Thai sauce with a different variety of noodle (e.g., Soba noodles, usually in Japanese dishes). The end result may not be a traditional Pad Thai but one that is suited to the customer’s palate or diet.

My motivation in creating and using the noddle bar assessment strategy was based on the following pedagogic questions: (1) Should assessments only be evaluations of learning or can assessments incorporate learning onto themselves? and (2) How can I make assessments interesting and useful for students? To answer the first question, assessment strategies that motivate better learning in students are the ones that allow students to explore information relevant to them (Stevens & Levi, 2013). Also, from an identity perspective (an area I work on as a researcher), individuals choose careers, professions, and roles that are related to their core identities, including personal, linguistic, and cultural, to name just a few (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Bordia & Bordia, 2015; Chreim, Williams, & Hinings, 2007; Ely, 1994; Slay & Smith, 2011). We also know that individuals consider the alignment of work, education, family, and values in choosing the right graduate degree or even the right school (Battle & Wigfield, 2003). International students also consider alignment of home and host cultural identities in making choices of graduate destinations (Bordia, Bordia, & Restubog, 2015 Bordia, Bordia, Milkovits, Shen, & Restubog, 2018). Therefore, it stands to reason that students may like to make such choices in terms of learning as well. The response to my second question is also linked with the social identity theory. Individuals engage with activities based on perceived similarities with their identities (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). For example, we may undertake projects at work based on our interests, experiences, and expertise because we perceive similarities between these activities and who we are (i.e., identity). Again, it seemed likely that students would see assessments that have some personal relevance to their lives as interesting and worth putting effort into.

I write this chapter as a course convener (responsible for all aspects of the course, including delivery, assessments, grading, etc.) of a graduate level course on cross-cultural management. This course is part of a suite of courses recommended for all management students but necessary for international business students (the business school offers MBA as well as several master’s degrees, such as Masters of International Business, Masters of Marketing). This course is not recommended during the students’ first year of studies but, in some cases, students will enroll in this course in the second semester of their first year. I have been convening this course for eight years (2010–2018) and have been using the noodle bar assessment strategy for this period of time.

In the rest of the chapter, I briefly discuss the experiential learning literature followed by how a student-led assessment strategy fits within the parameters of experiential learning. Following this, I discuss the learning objectives of the assessment strategy, experiential learning cycle, evaluation of learning effectiveness, benefits, challenges, best practices, and transferability of the assessment strategy, contributions to the literature, limitations and future pedagogic directions, and conclusion.

Review of Experiential Learning Literature and Fit of Student-Led Assessment Strategy

Seminal works on learning mechanisms by psychologists such as Piaget, Dewey, and Lewin collectively propose that knowledge generation is predicated upon individuals’ experiences and the ability to transfer such experiences into a set of theoretical and/or practical information that can guide future experiences (Kolb & Fry, 1975). Influenced by this body of research, Kolb (1984) created a model of learning based on experiences. Given that experiential learning is based on students’ ability to experience, and therefore learn, it is inherently learner-centric and allows students to make some decisions on what they wish to learn (Kolb, 1984). Experiential learning cycles include specific experiences, observation and reflection on these experiences, the formation of abstract constructs based on the experiences and reflections, and finally the testing of these new constructs in future experiences (Kolb, Boyatzis, & Mainemelis, 2001). Experiential learning also includes adaptation and interaction with the environment and allows students to come to a decision on what to learn and how to learn based on active experimentations (Kolb & Kolb, 2005). Such adaptations include the experiences to be internalized by individuals at cognitive, emotional, perceptual, and behavioral levels (Kayes, Kayes, & Kolb, 2005).

The importance and difficulty of creating instructor-led cross-cultural experiential learning is well documented (e.g., Earley & Peterson, 2004; Gonzalez-Perez & Taras, 2014 Taras & Ordeñana, 2014). Instructors, in such courses, create several cross-cultural experiences through examples, cases, current events, and even discussions of humorous anecdotes. However, there is no surety that such activities in a class seem personalized to all students due to the limitation of instructors’ experiences and hence schematic network. Hence more is needed in order to motivate students to internalize experiences to create theoretical perspectives that can be translated to action in the students’ work life.

The application of experiential learning has happened successfully in a variety of learning contexts, both formal and informal. In student contexts, experiential learning has been used in classroom activities (see Carolyn Buie Erdener’s project in Taras et al., 2014), short-term work internships (see Adam Jones and Greta Meszoely’s projects in Taras et al., 2014), study abroad programs (Gonzalez-Perez, 2014), and intercultural and international group work (Crossman & Bordia, 2012 Taras & Ordeñana, 2014). Much of the application of experiential learning has been in learning activities that have subsequently been evaluated for learning effectiveness. To the best of my knowledge, assessments themselves have been a product of learning in the context of experiential learning. Given the importance of assessments in formal learning and degrees, building experiential learning into the assessment process is likely to benefit students in terms of learning during assessment preparations and subsequently internalizing the assessment experience into their knowledge base. Hence, the inclusion of student-led assessments in the spectrum of activities on experiential learning is important.

Student-led assessments can help students to choose topics of assessment that take into account their prior educational, work, and cultural experiences, providing them the motivation to learn more on topics that interest them and may be useful in their future career needs. Individuals learn best when they have some prior knowledge of the context of the learning (Tobias, 1994). Also, motivational research suggests that individuals are motivated to gather knowledge on areas that they find relevant to their life/work experiences or on topics they see as beneficial to their future endeavors (Shepard, 2000). The diversity in the student population in terms of culture (domestic, international, and third/hybrid culture students), careers (managers, physicians, and diplomats), and educational backgrounds (management, social sciences, international relations) means that any one set of assessment is unlikely to be personalized for most of the students in any given year. Hence, allowing students to choose their own assessment context (i.e., a case) and theoretical perspective (mostly cross-cultural theories but sometimes additional theoretical perspectives from management or the social sciences) in implementing effective workplace decision-making is important for a diverse population of students. These features underpin my assessment structure in the graduate level cross-cultural management course. Along with a broad understanding of all areas in the course (see course outline in Appendix), students also have the freedom to develop expertise in areas of personal and professional interests.

Students are provided with a programmatic approach to the course assessments. First, they are asked to identify a real-life case and find a set of cross-cultural problems in it. A real-life case may be one that has occurred in the past (e.g., Toyota’s car-recall and delay in the CEO’s apology statement in the US market). Students may also choose to write about fictitious but realistic cases they have identified from textbooks or other outlets. In such cases, I ask students to show the case to me in the context of the textbook or other publications to make sure that the student does not have direct access to theories that have already been used by academics to explain and recommend actions in relation to the case. Alternatively, if the material suggests that the student will have undue advantage, but the student is very keen on the case, I ask the student to utilize other theoretical perspectives and come up with a new set of actionable recommendations. In some cases (only a few over the years), students will have their own case based on work experiences and will write up a two-page case for me to consider before moving forward with the assessments. The students are asked to discuss their case choice with me. A cross-cultural problem is defined as an action or perception of (including misunderstanding) action based on differences in cultural values (Arnett, 2002). The problem may not be visible to both parties involved in the action or perception. Nevertheless, negative relationships can be a result of cross-cultural problems. Second, for the first assessment, based on students’ identification of the most important cross-cultural problem, they are asked to choose an appropriate cultural theory and conduct an in-depth literature review of the theoretical aspect of their choice. I allow students to identity the most important cross-cultural problem based on their interpretation of the case as the perception of any problem can have negative effects even if others do not agree to the problem (Arnett, 2002). Students once again run their cases and theoretical choices by me to ensure alignment between the two and receive personalized consultation on the geographic, cultural, and political context of the case. Such individualized advice motivates students to develop some regional expertise, which is vital to the success of international business (Taras, Kirkman, & Steel, 2010). Third, the final assessment is a report to the organization (this is not sent to the organization but I assume the role of the CEO of the organization and assess the report in terms of background research, applicability, and professional style of the report). Students are asked to assume the role of a cross-cultural consultant, analyze the case, and provide recommendations for better practices.

Learning Objectives and Experiential Learning Cycle

The assignments provide opportunities for personalized learning for students so they gather knowledge on broad areas of the course and also develop expertise on a chosen topic. As mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, I call this personalized assessment program the noodle bar assessment strategy. Just like at a noodle bar where we choose our own set of ingredients (noodle, sauce, and meat/veg.), my students choose their own ingredients (case, theory, practice) to create a holistic set of assessments that are rich in contextual, theoretical, and practical implications. In week 1 of class, I discuss this strategy with the students and explain the concept of the noodle bar assessment. I discuss how the case is the noodle as it provides context to the rest of the assessment activities. Like the noodles provide bulk to the dish, the case provides a sizable chunk of the information necessary to contextualize and understand student’s theoretical choices and practical recommendations in the assessments. Like the sauce flavors the dish, the theoretical perspectives chosen by the students provide essence to the assessments, providing rationale for the analysis of problems as well as practical recommendations to the organization. Finally, just as the meat/veg provide nutrition to the dish, practical recommendations presented by the students can allow organizations to avoid past mistakes or rectify them in the present time.

In a programmatic approach to the noodle bar assessment strategy, I ask students to consult with me about a case by the end of week 3 of the semester (12 weeks). I meet students individually, ask them to describe their case and provide a rationale as to why this case interests them (e.g., a student from Australia picked Starbuck’s inability to run a profitable business in Australia and having to close down majority of their stores in the country). I then ask them to describe one important cross-cultural problem they see in the case while alerting the students to the fact that they will have to identity others later in the semester (e.g., customer care was perceived as impersonal at Starbucks as Australians are used to neighborhood baristas knowing them personally). Some of these problems are overtly discussed in the case write-up (published or unpublished documentation of the case) while others may be inferred by the students. Following this, I ask students to consider a theoretical perspective that resonates with the problem. For the example above, the student suggested that Australia is a more communitarian society with the government and local members of society taking care of each other and therefore an impersonal coffee shop was not appealing. I allow students to interpret the problem and theoretical connection to some degree but make sure that they are not erroneously analyzing any aspect of the case or theory. The rationale behind this is that individuals are likely to interpret different problems (or no problem at all) based on their schema and life experiences. Whether others evaluate the problem to be authentic or not, a perceived problem can lead to cross-cultural challenges.

In assignment one, which is due end of week 6, students are asked to consider the abovementioned key problems from the case. The end product of the first assignment is a literature review on the theory after a brief description of the case and a rationale for the use of the theory. If the theory is an extensive model of correlated constructs (e.g., Hofstede’s model has five key constructs: individualism and collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity and femininity, and long- and short-term orientation), then I ask students to choose one construct for the first assignment. Students are asked to review the literature for the origins of the theory or construct followed by an in-depth literature review of the research done in international business utilizing the theory or construct and any criticism that may have been discussed by researchers in the literature. Finally, students have to provide examples of how the theory or constructs may be applied in the workplace. In short, through this assignment, I expect students to become experts on the theory or construct of their choice and be able to apply it in the context of the workplace. Through this activity, I hope for my students to achieve the three lower levels of Bloom’s taxonomy: knowledge, comprehension, and application of the theoretical construct.

The first assessment in this scheme requires students to first internalize or experience the case. Because the case may not be a “lived in” experience of the individual (although some students will create a case based on their own work experiences), I encourage students to read media releases or other communications on the case in order to create a holistic understanding of the case. For example, students may look at national or international media discourse on a case (e.g., why IKEA failed the first time in Japan but later succeeded with a revised strategy). For contemporary cases, students also look at social media discourse on the case to understand public opinion. This allows students to experience the case as best as one can without being a part of it (Kolb & Kolb, 2009a). From this experience, students observe cross-cultural problems within the case and reflect on the possible theories or literature that can explain the problems. Once they have developed an understanding of the theories, via their preparation for the in-depth literature review, they are in a position to synthesize their reflections into abstract concepts (Kolb & Kolb, 2009b).

The final assessment, due end of week 12, addresses the three higher order levels of the taxonomy: analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. However, the lower levels are also addressed for other theoretical perspectives. Prior to the assessment, I meet the students again and discuss the requirements of the assessments. Students are asked to further analyze the same case and look at three key problems, one of which is the one they have already looked at in assignment one. After identifying two more problems (sometimes these are associated or hierarchically linked problems), students are asked to link each problem to a short literature review of a theoretical perspective (the first problem and its theoretical link remains). In doing this, the students have to undergo the three lower levels of the taxonomy again. After the choice of three problems and three theoretical constructs have been made, students have to write a report to the organization in which they are expected to collectively synthesize the three literature and associated problems to come up with recommendations for better practice (usually three but numbers can differ). In suggesting recommendations, students are asked to evaluate the recommendations based on available information on various aspects of the organization’s background. For example, suggesting expensive training programs for a small- or medium-size enterprise or practices that stand against local religious or cultural practices may not be viable options.

For the final assignment, based on their experience by reading various narratives in relation to the case (organizational, public and sometimes governmental opinion on the case), students are able to engage in reflective observations. While most students do not contact the organization in question, they consult with other students in the class to check for potential flaws in their reflections. Some students, who write their own cases based on personal experiences, often seek the advice of other stakeholders in the case (often current or former colleagues) to test their assumptions of the case. Coupled with case reflections, the theoretical/literature review helps students develop abstract concepts, and they are able to recommend actions that the organization can take to rectify their problems/mistakes. If the cases chosen by the students are dated and future actions have already been taken by the organizations and are available for students to read, I ask students to make additional recommendations. Such additional recommendations may be novel in nature or provide further details on prior actions. Given that individuals view cross-cultural differences based on their own cultural schema (Arnett, 2002), students often come up with novel recommendations that have the potential to add value to extant problem-solving of the case.

Benefits of the Noodle Bar Assessment Strategy

The noodle bar assessment strategy has several benefits for students. First, students develop different skills through the assessments. Students learn to respond to different types of readership. Any training for managerial roles needs to account for communication to different audiences (Tobias, 1994). By assuming the role of a scholar in evaluating one assessment and that of a CEO in another, I encourage students to present their arguments effectively for different audiences. Related to the above benefit, students also develop effective writing skills in two genres (literature and report writing) and the ability to transfer knowledge from one assessment to another. Both writing skills and transferability of academic knowledge to the workplace are cornerstones of education (Bordia et al., 2018).

Second, students are encouraged to take a holistic approach to a case by engaging with media coverage and other publicly available information. Taking a 360-degree view of a problem is vital for any sustainable and effective solution in the workplace (Shepard, 2000). The current assessment strategy allows students to learn this.

Evaluation of Learning Effectiveness

The assessments are evaluated by me. Students are provided with assessment rubrics at the beginning of the semester (see course outline for rubrics in Appendix). I also explain these rubrics to students in the first seminar and again two weeks before the due date of the assignments. I tell the students that for the first assignment they should expect me to stick to my role as an academic in the field of expertise in marking their assignment. For the final assignment, I tell them that I will assume the role of the CEO of the organization in the case. In doing so, I will be looking for a professionally written report that briefly explains to me the relevant literature used to justify the analysis and recommendations. I remind the students that a CEO may not be cognizant of the literature on cross-cultural management and information has to be appropriately presented to an educated, professional, but not expert audience. In addition, I upload slides on literature review/research essay writing and professional report writing styles on the course website. Students are asked to follow such formats and writing styles for the assignments. While I do offer to read outlines and drafts of assignments before submission, not many students take me up on this offer. The ones that do take me up on the offer usually submit a good final draft.

Some of the common challenges students face in the first assignment are (in order of severity of challenges) as follows: (1) instead of a literature review, students use the literature to write a report to the organization (essentially a weaker version of the final assessment instead of the first), (2) literature review is not in-depth, does not include key citations, or is only specific to a region (e.g., a review of individualism and collectivism only in the Middle-East), and (3) literature reviewed is good but writing is not (often a concern for international students). Students receive comments based on the nature of their challenges on the final draft. I tick the right space on the rubric when I give them back the marked assignments. If the assignments receive ticks from satisfactory to needs more work, there are comments on these issues. For example, for the first challenge above, the comments may be

In essence you have done the final assessments in the first instance. Your job in this assessment was to do an in-depth literature review of the theory/literature you employed to understand the major problem you isolated in the case. This assignment was not about recommending solutions to the organization, but to show that you understand a key theoretical perspective applicable to the case.

I also provide summative assessments of the key challenges and why students have lost marks in this assignment in class.

For the final assignment, some of the key challenges are (in order of severity of challenges) as follows: (1) analysis of problems or recommendations not adequately explained for a professional audience (i.e., not written in a persuasive way, not guided by adequate theoretical or practical justifications), (2) literature review to educate the professional audience and justify the analysis/recommendations not focused enough (e.g., the construct of power distance is explained but not the outcome of this construct on workplace behavior), and (3) report is not professional in nature (e.g., not formatted well, does not have headings/subheadings, long paragraphs, colloquialism in writing). Once again, students receive ticks in the appropriate sections of the rubric and any weaknesses in the assignments receive comments such as

your report had good quality literature review, analysis of the problems, and recommendations, but the format was not appropriate for a professional report. I saw several long paragraphs without thematic subheadings that could parse the content. It is appropriate to have short paragraphs and additional sub-thematic headings. This helps busy/time-poor executives to see a ‘road map’ for the content and allows them to read the report quickly.

Challenges of the Noodle Bar Assessment Strategy

Many students, over the years, have appreciated the noodle bar assessment strategy, including providing qualitative comments in anonymous course evaluations: “I really love the assignments. I thought it brought out what this course was really about”, “The assignment format was good, giving enough scope for postgraduate students to explore areas of interest”, and “The course structure was relevant to the contemporary issue of cross-cultural challenges in corporations. Individual case studyprovided an interesting look into the cultural aspect of the business and its implications.” I have also received very high teaching evaluations (4.25 out of 5). There are, however, several challenges for students and the course convener in relation to this assessment strategy. I outline the challenges for students first.

First, international students, who are non-native English speakers, face some difficulties in the writing of the assignments. Both academic and professional English may be a challenge for such students. However, the assessment strategy also provides such students a platform to improve upon their English writing capabilities. Such students are encouraged to start their assignment drafts well ahead of time, seek additional consultation with the course convener, as well as academic and professional writing services within the university (usually offered free of cost to the students).

Second, short timeframe for students to choose cases (within three weeks) often is a challenge for students with limited workplace or professional engagement. Usually, MBA students are very good with this aspect of the assessment strategy. However, several other master’s degree students may not have mandatory work experience requirements. Such students, especially if they are international and straight out of their undergraduate degrees, struggle to find cases in the short timeframe.

Finally, assignment one appeals to some types of learners. Usually, learners with an academic orientation perform better in assignment one. Such learners are often (but not exclusively) recent graduates of a western style undergraduate degree or PhD students who take the course as an elective. These students have recent experiences in literature reviews, can critique the literature, and are proficient in academic writing. Students who have limited or dated experiences in literature reviews and academic writing (e.g., experienced practitioners who did their earlier university degrees several years back, international students coming from countries where exams are the primary mode of assessments) find assignment one challenging. Assessment two appeals to students who have extensive work experiences and are adept at professional writing.

From a course convener’s perspective, the challenges include, first, a larger than average number of consultation hours with students. Most universities suggest 2–3 hours of consultation per week during the semester. However, the noodle bar assessment strategy, on an average, requires me to consult with students for 5–7 hours. The consultation hours are not the same each week, and usually peak to 10–12 hours, before due dates for assignments. Second, each assessment is unique and takes longer to mark. Once again, universities suggest about 30 minutes for an assessment that is around 30% of the course mark. Given that each assignment is unique, deals with a different case, a variety of literature reviews, different problem analyses and recommendations, assessments take at least 45 minutes to mark, with the more complicated assignments that are likely to get lower marks requiring longer time. While I do not get a lot of assignment outlines or drafts prior to submission, this does take additional time and prospective course conveners wishing to use the noodle bar assessment strategy would be wise to factor this into their timeframe budgeting for the course. Overall, I would not recommend such assessment be used for courses where enrolment is over 60 students unless the course convener has access to additional markers. Also, I would not recommend course conveners undertake this assessment strategy for more than one course each semester.

Transferability of the Noodle Bar Assessment Strategy

The noodle bar assessment strategy is applicable to most graduate courses in international business and management that have the following components associated with its content: literature/theory, real-life/realistic cases, and practical outcomes. While I have not taught courses in international relations, healthcare management, or political sciences, I have had students from these disciplines who have enrolled in my courses and have informally said to me that they liked this assessment strategy. In an unsolicited email, one such student said that he was “grateful for your acceptance of the topic of cultural aspects of indigenous Australians and because it has application in health care, was of interest and value to [me]”.

I have also used this strategy for a qualitative research methods course where the first assignment was based on a literature review and the final one was a proposal for a research project in the student’s chosen discipline. The assessment strategy has worked well for the research methods course. I have received an average of 4.7 out of 5 for this course and some anonymous comments include “I was able to pick lots of important tips from her and I believe that those will help me doing my research and publishing my work. Examples she provided during the course were the most important strength of the course”, and another student wrote “Dr Bordia is a strong proponent of the subject matter. She has worked in the field and is able to teach the subject from experience (both good and bad) but also was able to compare and contrast with quantitative approaches.”

In addition, this assessment will be of value to executive MBA courses where students come with a vast array of practical experience and often undertake the degree as a quest to personalized problems they have encountered in their workplaces. A more extended version of this assessment strategy can also be utilized in Doctorate of Business Administration (DBA) degrees where enrolled research students seek research experiences that resonate with their workplace experiences. Students undertaking individualized industry research or internship experiences can also benefit from this assessment strategy.

This assessment strategy may be applicable to elite or advanced year undergraduate courses. Some undergraduate courses in later years require students to have a high grade point average. I anticipate the students in such courses will have good time management skills and may be able to multitask on such assessments. Such an assessment strategy may be particularly suitable in undergraduate courses that have workplace or research internship components. Also, undergraduate students may need additional consultations and the submission of an outline of the assignments should be made mandatory if the noodle bar assessment strategy is implemented.

Contributions to Experiential Learning Practices

The noodle bar assessment strategy, as all pedagogic activities that require extensive effort, yields several benefits for students. First, students develop theoretical expertise on a section of the cross-cultural management literature by engaging in an in-depth literature review including understanding the origins of the theoretical construct, the identification of research gaps, critical evaluation of the literature, and application of the literature in the workplace context. Given that students will not remember all aspects of a course in years to come, they are likely to remember the aspects that they put focused effort in and choose to understand on their own volition. Second, students develop some regional expertise in relation to the case they choose. Intra-country differences are often neglected in international business literature (Tung, 2008) and geographic, political, linguistic, and religious challenges are often underplayed in the broader international business literature (Bordia & Bordia, 2015 Brannen, 2004 Kostova & Roth, 2003 Luo & Shenkar, 2006). Hence, students’ ability to analyze such challenges stemming from the case adds significant value to learning about the international business context and how some organizational practices that work well in one context may not work in another. Third, by creating, assessing, and recommending action in a professional report format, students gain important skills in terms of activities they have to undertake at the workplace.

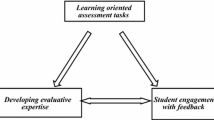

In this chapter, I have introduced a student-led assessment model that has yielded experiential learning for my students. In addition to the noodle bar assessment strategy, I have other assessments that allow for experiential learning in the course. Students are provided with substantial time for group-led problem-solving activities via cases that I introduce in class. Through such activities, students achieve two crucial employability skills—creative problem-solving and teamwork. To enable students’ familiarity with digital learning, the course also includes an assessable online discussion forum. Each week a set of questions based on the topic of the week are presented to students and they are asked to respond to the questions based on their experiences and/or extant knowledge of the literature. This includes a week of no seminar when students are asked to work through two cases of and provide an in-depth analysis of the cases. This week’s activities are a training for the case analysis in the assignments in the noodle bar assessment strategy. Through such a peer-learning platform, students have the opportunity to collaborate, learn from each other, show leadership, and sometimes handle conflict—all of which are identified by industry as important skill gaps among university graduates. Students have responded very positively to this pedagogic structure: “Class discussions and sharing stories really helped make the concepts relevant”, “a very open and engaging style and… very supportive and receptive to all contributions which made the class more willing to contribute and therefore made for very interactive seminars”, and “The group activities… is very useful and interesting… makes the 3-hour seminar feel like one!” Based on my assessment strategies in the cross-cultural management course, I present the following model of experiential learning through innovative assessment practices (Fig. 17.1).

Figure 17.1 illustrates the interconnected elements of the assessment strategy and how they collectively provide experiential learning to students in the course. First, the students’ personal and professional interests are reflected in the student-led assessment choices (i.e., the case). Second, the choice of theoretical perspectives by students lends to theoretical expertise unique to each student. Third, both the abovementioned elements are facilitated by personalized consultation from the course convener. Finally, peer-learning is facilitated through the in-class and online discussions.

Limitations and Future Pedagogic Directions

In my implementation of the noodle bar assessment strategy, I have received positive feedback from students (both quantitative and qualitative). However, I have not taught the discussed courses with any other assessment strategy. Therefore, I am unable to compare student learning or performance with any other assessment strategy. Future pedagogic implications of this strategy may indicate if the application leads to certain specific learning that other strategies would not. Also, the implication of the assessment strategy with undergraduate students may lead to further pedagogic improvements of the strategy. The cases students typically choose have been historic and publicly available in nature. It would be interesting to see how students cope with evolving cases (real life or simulated) and whether this requires further innovation in the assessment strategy. Finally, students have worked by themselves on the assessments and much of the consultation with the course convener has been face-to-face. Further innovation may be needed if the assessment strategy were to be used in group and/or online assessments.

Conclusion

The assessment strategy outlined in this chapter should be of value to any course that requires students to come with some degree of life and or work experiences. It is valuable to courses that require students to analyze information from multiple perspectives. Most importantly, it is valuable in areas of education where there is no one specific way of problem-solving and where contextual information has to be integrated in order to achieve successful outcomes. While I have outlined how the noodle bar assessment strategy can be used in developing experiential learning in international business students, I hope this chapter assists academics in other disciplines to achieve experiential learning for their students.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2002). The psychology of globalization. American Psychologist, 57(10), 774–783.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

Battle, A., & Wigfield, A. (2003). College women’s value orientations toward family, career, and graduate school. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62(1), 56–75.

Bordia, S., & Bordia, P. (2015). Employees’ willingness to adopt a foreign functional language in multi-lingual organizations: The role of linguistic identity. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(4), 415–428.

Bordia, S., Bordia, P., Milkovits, M., Shen, Y., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2018). What do international students really want? An exploration of the content of international students’ psychological contract in business education. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1450853

Bordia, S., Bordia, P., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2015). Promises from afar: A model of international student psychological contracts in management education. Studies in Higher Education, 40(2), 212–232.

Brannen, M. Y. (2004). When Mickey loses face: Recontextualization, semantic fit, and the semiotics of foreignness. Academy of Management Review, 29(4), 593–616.

Chreim, S., Williams, B. E., & Hinings, C. R. (2007). Interlevel influences on the reconstruction of professional role identity. Academy of Management Journal, 50(6), 1515–1539.

Crossman, J., & Bordia, S. (2012). Piecing the puzzle: A framework for developing intercultural online communication projects in business education. Journal of International Education in Business, 5(1), 71–88.

Earley, P. C., & Peterson, R. S. (2004). The elusive cultural Chameleon: Cultural intelligence as a new approach to intercultural training for the global manager. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 3(1), 100–115.

Ely, R. (1994). The power in demography: Women’s social constructions of gender identity at work. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3), 589–634.

Gonzalez-Perez, M. A. (2014). Study tours and the enhancement of knowledge and competences on international business: Experiential learning facilitated by UNCTAD virtual institute. In V. Taras & M. A. Gonzales-Perez (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of experiential learning in international business (pp. 539–549). NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gonzalez-Perez, M. A., & Taras, V. (2014). Conceptual and theoretical foundations: Experiential learning in international business and international management fields. In V. Taras & M. A. Gonzales-Perez (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of experiential learning in international business (pp. 12–16). NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kayes, A. B., Kayes, D. C., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Experiential learning in teams. Simulation & Gaming, 36(3), 330–354.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4, 193–212.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2009a). Experiential learning theory: A dynamic, holistic approach to management learning, education and development. In S. J. Armstrong & C. V. Fukami (Eds.), The Sage handbook of management learning, education and development. London: Sage.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2009b). The learning way: Meta-cognitive aspects of experiential learning. Simulation and Gaming, 40(3), 297–327.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kolb, D. A., Boyatzis, R. E., & Mainemelis, C. (2001). Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. Perspectives on Thinking, Learning, and Cognitive Styles, 1, 227–247.

Kolb, D. A., & Fry, R. E. (1975). Toward an applied theory of experiential learning. In C. Cooper (Ed.), Theories on group process. London: John Wiley.

Kostova, T., & Roth, K. (2003). Social capital in multinational corporations and a micro–macro model of its formation. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 297–317.

Luo, Y., & Shenkar, O. (2006). The multinational corporation as a multilingual community: Language and organization in a global context. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(3), 321–339.

Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29(7), 4–14.

Slay, H. S., & Smith, D. A. (2011). Professional identity construction: Using narrative to understand the negotiation of professional and stigmatized cultural identities. Human relations, 64(1), 85–107.

Stevens, D. D., & Levi, A. J. (2013). Introduction to rubrics: An assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote student learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Taras, V., Berg, D. M., Erdener, C. B., Hagen, J. M., John, A., Meszoely, G., … Smith, R. C. (2014). More food for thought: Other experiential learning projects. In V. Taras & M. A. Gonzales-Perez (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of experiential learning in international business (pp. 131–148). NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Taras, V., Kirkman, B. L., & Steel, P. (2010). Examining the impact of culture’s consequences: A three-decade, multi-level, meta-analytic review of Hofstede’s cultural value dimensions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 405–439.

Taras, V., & Ordeñana, X. (2014). X-culture: Challenges and best practices of large-scale experiential collaborative projects. In V. Taras & M. A. Gonzales-Perez (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of experiential learning in international business (pp. 131–148). NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tobias, S. (1994). Interest, prior knowledge, and learning. Review of Educational Research, 64(1), 37–54.

Tung, R. L. (2008). The cross-cultural research imperative: The need to balance cross-national and intra-national diversity. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(1), 41–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: Course Outline

Appendix: Course Outline

Please note:

-

1.

Name and number of course has been masked as the course is the intellectual property of the university.

-

2.

In the interest of space and word limit, only the rubrics of the two main assignments outlined in the noodle bar assessment strategy have been presented. For further information, please contact the author.

Course Schedule

Week | Summary of activities |

|---|---|

1 | Seminar: Introduction |

2 | Seminar: Models of cross-cultural management |

3 | Seminar: Cross-cultural teams in organizations |

4 | Online case studies (no Seminar): Theory to practice—intercultural case studies |

5 | Seminar: Intercultural communication and multilingualism in organizations |

6 | Seminar: Negotiation and conflict in cross-cultural management |

7 | Seminar: Diversity in the Australian workforce |

8 | Seminar: Global careers—expatiation and repatriation |

9 | Seminar: Leading in a multicultural organization |

10 | Seminar: Global organizations—MNCs and off-shoring |

11 | Seminar: Employee-employer relationships and cross-cultural management |

12 | Seminar: Cross-cultural training: Effectiveness and myths |

Assessment Tasks

For the main assignments in this course, you will have to take a programmatic approach. You will have to take the following steps:

-

1.

Your first task is to identify a case study which has a problem in relation to cross-cultural management. The case may be found in popular media releases, practitioner and/or academic publications, hypothetical cases from books or journal articles other than the ones recommended in this course or from personal experiences (if you take this approach, please maintain confidentiality of all parties involved). Once you have identified a case, please discuss the case with me before you go on to the next steps. This should be done by the end of week 3 so you have enough time to work on the assignments.

-

2.

Identify the key cross-cultural construct in the case (any realistic case will have several issues in relation to culture. You will have to identify the most important one for the given case) and write a research essay for Assignment 1 (2000 words +/− 10%; 30%, to be submitted on Friday week 6 by 4 pm). In this essay, you should outline the emergence of the theoretical construct, further developments based on the research literature, application to contemporary global organizations, and any criticism the construct has encountered from researchers and practitioners in the area. When you submit the essay, please submit a copy of the case as well.

-

3.

For Assignment 2, write a report on the case you have identified (2000 words +/− 10%, 30%, to be submitted on Friday week 12 by 4 pm). In writing the report, you will have to imagine that you are a management consultant with expertise in cross-cultural issues. Your job is to identify what went wrong in the management style or decision-making process in this context. Use the theoretical perspectives you have learned in the course to identify the mistakes that were made. Recommend how these can be rectified based on the research literature.

Assessment Task 1: Research Essay

Details of task: Identify the key cross-cultural constructs in the case (any realistic case will have several issues in relation to culture and write a research essay). In this essay, you should outline the emergence of the theoretical construct, further developments based on the research literature, application to contemporary global organizations, and any criticism the construct has encountered from researchers and practitioners in the area. When you submit the essay, please submit a copy of the case as well.

Assessment Rubric

Excellent | Good | Satisfactory | Needs some more work | Needs much more work | Mark | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Content | /20 | |||||

Detailed discussion of the theoretical perspective. Examples provided to illustrate the theory in an organizational context. Discussion of relevant issues in relation to the question. Inclusion of citations from key research to develop argument. Applications/recommendations for the contemporary global organization. | ||||||

Structure, language, and referencing conventions | /10 | |||||

Structure of essay: Introduction: Thesis statement, definition of key terms and outline of argument. Main Body: Logical discussion, persuasive arguments, and clarity in the author’s ‘voice’. Conclusion: Summary of main argument and no new ideas or references. Language: Appropriate paraphrasing, quoting and summarizing from sources. Appropriate sentence structure, grammar, and word limit. Referencing: All ideas taken from sources are appropriately referenced. Reference list matches in-text references and is written in a consistent style. | ||||||

Total Marks: 30 | ||||||

Assessment Task 2: Report on case study

Details of task: Write a report on the case you have identified. In writing the report, you will have to imagine that you are a management consultant with expertise in cross-cultural issues. Your job is to identify what went wrong in the management style or decision-making process in this context. Use the theoretical perspectives you have learned in the course to identify the mistakes that were made. Recommend how these can be rectified based on the research literature.

You must have the following sections in your report:

Cover page

Executive summary

Introduction

Literature review

Analysis of the problem

Recommendations

Summary

References

Assessment Rubric

Excellent | Good | Satisfactory | Needs some more work | Needs much more work | Mark | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Content | /20 | |||||

Appropriate identification of the problem Detailed discussion of relevant theoretical perspective(s) in relation to the problem Discussion of relevant contextual issues associated with the problem Inclusion of key citations from research to analyze the problem Creative and effective recommendations to rectify the problem Detailed description of the recommendations (including a budget if necessary) Recommendations presented in order of priority Links between the recommendations and existing theories/research Rationale behind the choice of recommendations Suggestions on relevant follow-up activities when necessary | ||||||

Report format | /10 | |||||

Report has all the sections suggested in the case study Each section consists of information relevant to that section (4 marks) Professional format of the report Appropriate sentence structure, grammar, and word limit Appropriate paraphrasing, quoting, and summarizing from sources All ideas taken from sources are appropriately referenced Reference list matches in-text references and is written in a consistent style | ||||||

Total Marks: 30 | ||||||

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bordia, S. (2019). Experiential Learning Through Student-Led Assessments: The Noodle Bar Strategy. In: Gonzalez-Perez, M.A., Lynden, K., Taras, V. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Learning and Teaching International Business and Management. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20415-0_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20415-0_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-20414-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-20415-0

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)