Abstract

Small-, medium-, and micro-sized enterprises (SMMEs) constitute a vast majority of businesses in Cameroon and are a vital source of its economic growth, dynamism, and flexibility. SMMEs as economic agents are not only built on their intrinsic qualities, but also rely on information from the business environment. This chapter assesses the impact of entrepreneurial characteristics on the performance of SMMEs. The data used for this study are ‘the General Census of Companies in Cameroon,’ conducted with 93,969 companies by the National Institute of Statistics (INS). The study uses multiple regressions to assess the direct effects of entrepreneurs’ characteristics on the performance of their SMMEs. A statistical analysis of the data reveals that men (60 %) are more entrepreneurially active than women and are mostly less than 50 years old (80 %). Econometric analyses show that characteristics such as gender, age, training, level of education, country of origin, and the share of capital of an entrepreneur significantly influence a SMME’s performance. Further, the social networking capacity of entrepreneurs facilitates economic action and allows them to expand the scope of their businesses by saving resources and leveraging exclusive resources and opportunities. These relationships help the entrepreneurs transform human and financial resources into profit. The level of education feeds into a persistent entrepreneurial logic, and vocational training received by Cameroonian entrepreneurs determines their career opportunities and the performance of their ventures.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Small-, medium-, and micro-sized enterprises (SMMEs) are the backbone of all economies and are a vital source of economic growth, dynamism, and flexibility in both industrialized countries and emerging economies and developing countries. SMMEs played an important role in innovation, job creation, and the development of industrialized countries during the twentieth century (Quiles 1997). In developing countries, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) , SMMEs are the dominant form of business, representing between 95 and 99 % of the business depending on the country: about 99 % in Cameroon with a strong representation (89 %) of individual companies (INS 2009), 93 % in Morocco, 90 % in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and 95 % of manufacturing activity in Nigeria (OECD 2006). Despite this weight, the contribution of SMMEs to the gross domestic product (GDP) is estimated at less than 20 % in most African countries, while it is up to 60 and 70 % in OECD countries (Admassu 2009). In addition, SMMEs operating in sub-Saharan African countries, on average, employ less than 30 % of the workforce in the manufacturing sector, while this proportion is 74.4 % in Asian countries, 62.1 % in the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, and 73.1 % in OECD countries (Ondel’ansek 2010). In Cameroon, SMMEs employ 61 % of the workforce and their contribution to GDP is estimated at 31 % (INS 2009).

Given this contrast, the various elements that contribute to the development of SMMEs, such as improved financial conditions through the creation of a bank for SMMEs, are not enough to boost the growth, development, and sustainability of these companies. This is due to the business environment characterized by, for example, technological breakoffs; profound changes in consumer habits; national and global economic crises; and sudden changes in national economies. In such a turbulent environment characterized by complexity, uncertainty, and dynamism, the mortality rate of these companies in the start-up and growth phases is still important (according to OECD 2001, 60 % of operational SMMEs do not pass the milestone of 40 years). One of the main factors behind the bankruptcy or death of emerging African SMMEs (Capiez and Hernandez 1998) is the lack of skills by entrepreneurs and/or corporate leaders to penetrate new markets (Kamdem 2011). Thus, we might actually invoke the fact that some key skills derive directly from an entrepreneur’s characteristics such as experience and training . An entrepreneur’s characteristics are thus considered as a factor that comes into play for the success, development, and sustainability of the business. Given the important role of entrepreneurs in the functioning of SMMEs (with strong representation of individual companies at 89 %), many published works highlight the significant impact of an entrepreneur’s characteristics on the performance of the business he/she manages (INS 2009). This effect is explained in relation to certain demographic, psychological, and behavioral characteristics of the entrepreneur as well as in relation to his/her management abilities and technical expertise. According to the Cameroon National Institute of Statistics (INS 2009), the characteristics of a Cameroonian entrepreneur are defined by his/her background (age, sex, level of study, nationality, and creation nature); triggering effects (region, professional training, belonging to a group, and religion); and environmental factors (the source of social capital, the legal form of the firm, technological innovations, and ICT usage).

A study by Lorrain et al. (2002) on entrepreneurs’ characteristics concludes that entrepreneurs who are most successful tend to be older, more experienced, more motivated, and more competent. Similarly, Aldrich and Davis (2000) in their study on the organizational advantage of social capital conclude that social capital, the social and relational environment of an enterprise, and an entrepreneur’s networking activities significantly influence the performance of his/her business. In addition, studies also show that the acquisition or development of skills, knowledge, and qualifications by an entrepreneur during the early years of the company (Gartner et al. 1999) through various forms of learning (Chabaud et al. 2010) has an influence on the growth of the company. Morris (1998) in his studies in entrepreneurship concluded that most SMMEs remain small and non-performing after several years of operations due to lack of experience of entrepreneurs. Thus, entrepreneurs’ characteristics are central to the performance of SMMEs and therefore constitute a management issue from the perspective of an increasingly strong cross-fertilization of research in entrepreneurship and human resource management (Chabaud et al. 2008). Entrepreneurship, being a dynamic process of creating and developing an organization in which the creator mobilizes and combines resources (human, information, material, and financial) to increase opportunities for a structured project, an entrepreneur would be both an actor of wealth creation and a subject of the value creation. Based on different paradigms of entrepreneurship (innovation, creation of organization, organizational emergence, value creation), an entrepreneur is the initiator of performance; that is, he/she is an economic agent and an engine of technological progress. He/she organizes, plans production, and bears all risks (Schumpeter 1935). Entrepreneurs have a special and indispensable role in the evolution of a liberal economic system. They are often at the source of destructive creative innovations (Schumpeter 1939). They create businesses and jobs, and contribute to the renewal and the restructuring of the economy.

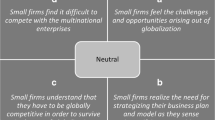

Schumpeter’s analysis (1935) emphasizes the place of an entrepreneur in the creation, growth, and corporate development processes. This place is all the more essential in the case of SMMEs, as an entrepreneur is a heroic figure in these types of businesses (Capiez and Hernandez 1998; Julien and Marchesnay 1988). In addition, the process of creating a new Cameroon social system through speedy business creation in 72 h (a decree signed by the Prime Minister of Cameroon in 2010 to alleviate the business creation process and thus ease start-up procedures for companies) puts an emphasis not only on the role of supporting organizations and following-up structures for entrepreneurs, but also takes into account the characteristics of entrepreneurs in ‘tying up’ their opportunities. In recognizing that the process of creating and developing SMMEs involves not only the characteristics of an entrepreneur, but also different features of an incubator organization and an entrepreneur’s socioeconomic environment, this chapter answers the question: What is the impact of entrepreneurial characteristics on the performance of newly created SMMEs in Cameroon?

Given the scarcity of publications on the impact of individual characteristics and qualities of an entrepreneur on the performance of SMMEs in Cameroon, this work attempts to fill this gap by assessing the impact of entrepreneurs’ characteristics on the performance of SMMEs. Analyzing and evaluating the effects of entrepreneurial characteristics on the performance of SMMEs can help us provide policy recommendations that can create a favorable environment for entrepreneurship in Cameroon. The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows: The following section reviews literature related to the theoretical foundations of entrepreneurial characteristics that influence the creation, development, and performance of SMMEs. Section 2.3 presents the methodology and data used in this work. The results are discussed in Sect. 2.4.

2 Literature Review

A big stream of literature highlights the significant impact of an entrepreneur on business performance (Cooper 1993; Allemand and Schatt 2010). As a majority of the SMMEs in Cameroon are individual enterprises (Alizadeh 2000) (having only one shareholder who also manages the company), their performance can be explained in relation to certain demographic, psychological, and behavioral characteristics of entrepreneurs as well as in relation to their abilities in management and their technical know-how. Entrepreneurs’ characteristics such as experience, education level, age, sex, and networking are used to explain the success or failure of a newly created company. Lorrain et al. (2002), studying the characteristics of SMME entrepreneurs, conclude that entrepreneurs who are most successful tend to be those who are older, more experienced, more motivated, and more competent. Cooper (1982) concludes that experience in creating or managing a business is a prerequisite for an entrepreneur’s success and contributes in one way or another to the performance of the created company. Yet, Van Beest et al. (2009) refute this assertion by stipulating that previous work experience has no influence on the success or performance of a newly created company. Smallbone (1990) also pays considerable attention to the influence that qualifications have on an entrepreneur’s sustainability or cession of a newly created company.

According to human capital theory, knowledge increases individuals’ abilities and contributes to the management of activities (Becker 1964), and some authors establish relationships between education, entrepreneurship, and success in economic activities and value creation (Davidsson 2002). Therefore, authors believe that (formal or informal) education and various individual experiences are factors that favor entrepreneurial activities. They suggest, for one, the influence of human capital on performance . Marvel et al. (2007), studying the experience, education, and original knowledge in technology of high-tech entrepreneurs, conclude that the human capital of ‘technological entrepreneurs’ gives them unique advantages. From the same point of view, Wright et al. (2007) show the positive influence of human capital characteristics on the success of technological entrepreneurship and business performance. Hambrick (2007), in a study on the growth of SMME start-ups, concludes that business performance depends on the leaders’ characteristics, including their training and experience. In the same vein, Allemand and Schatt (2010) analyze the impact of entrepreneurs’ training while simultaneously taking into account their experience and the ownership structure which determines both the incentives of the entrepreneurs and their constraints in decision making. They conclude that training reflects the cognitive base of executives, thus acting in the same way as other idiosyncrasies over their perceptions and interpretations of the situations that they face. Similarly, focusing their interest on training as part of managerial human capital, Castanias and Helfat (2001) state that this indicator is a source of value creation and corporate managerial rents. That is, training in colleges and universities pursued by some Cameroonian leaders should be synonymous with higher performance of the companies that they lead. Human capital is thus an essential characteristic of entrepreneurs.

Following criticism of individual characteristics, many authors have focused on the social and relational environment of a company and an entrepreneur’s networking activities (Aldrich et al. 1987; Aldrich and Dubini 1991). For Mizruchi (1996), the influence of an entrepreneur’s characteristics on a firm’s performance can also be explained by the fact of belonging to networks. That is, social relations and personal contacts that entrepreneurs develop throughout their lives can be very useful because they allow access to various benefits and advantages. In their study on access to social networks, Lin and Dumin (1986) conclude that contacts from entrepreneurs’ social networks are used to improve the performance of their businesses. The relationships which result from these are a valuable resource for conducting businesses as they facilitate economic action and allow entrepreneurs to expand their scope, to save their resources, and have access to exclusive resources and opportunities. According to Burt (1992), these networks help an entrepreneur to provide three categories of resources to the business: financial resources (such as cash, bank deposits, and credit lines), human resources (skills, charisma and intelligence, competences, and education), and information resources (recognition of opportunities). Neergaard and Madsen (2004) and Burt (2000) show that large networks with a high number of contacts are quite important for the development of entrepreneurial projects as they enable them to access resources held by other actors in the network. Similarly, having an extensive network of contacts could help a company’s performance (Baron 2007). Indeed, entrepreneurs having extended contacts should have less difficulty in finding, selecting, and retaining partners (customers, suppliers, distributors, etc.) and also in reducing their dependency on them. Similarly, maintaining more social ties will allow entrepreneurs to better market their products and reduce certain costs including those related to information search, decision making, fees paid to intermediaries, and trading activities (Plociniczak 2001). Certainly, many works highlight the importance of an entrepreneur’s social networking on the performance of his/her company (Batjargal 2001). However, only a few studies have been carried out in Cameroon on this issue.

In summary, this discussion leads to the following hypotheses:

-

(a)

The cognitive characteristics of an entrepreneur (training, level of education, experience) positively affect the performance of a firm.

-

(b)

Social networking abilities of an entrepreneur (quality of social capital) favor an improvement in a firm’s performance.

3 Methodology

For the purpose of our study, econometric modeling proves to be essential. The characteristics of an entrepreneur analyzed in this work are devoted to measuring the output of an entrepreneur in terms of the performance of the firm. Many authors (Gauzente 2011; Ananga et al. 2013) have focused on measuring the performance of a firm. However, they did not use the same measuring instruments. These countable indicators of a company are calculated from an assessment of the earning reports of a company and are associated with its economic and financial performance . Among other things we find: growth in sales turnover, production, added value, rough operating surplus, rough operating results, and net operating profits.

Based on Cooper’s model (1979), adapted by Lacasse (1990), which has proved to be a promising research approach to study the reality prevailing in Cameroon (INS 2009), this study assesses the impact of entrepreneurs’ characteristics on the performance of SMMEs. Next, we present our data source, the specification of the model, the choice of variables, and statistical analyses.

3.1 Data Source

Data used for this research are from the General Census of Enterprises (RGE) realized in 2009 by the National Institute of Statistics (INS). This census involved 93,969 companies and institutions operating in Cameroon. The survey represented 86.5 % of the tertiary sector, 13.1 % of the secondary sector, and only 0.4 % of the primary sector. The main objective of the census was to have a better understanding of the current situation of enterprises and institutions in order to develop strategies for public authorities, economic operators, and other analysts to effectively play their roles. In general, information in this survey is related to companies, managers, and employees; the business environment; technological innovations; and use of ICT and production stock. For the present study, we had to extract data relative to firms, their managers (entrepreneurs), and the business environment. This led us to specifically focus on an entrepreneur’s characteristics (age, sex, level of education, professional experience, social networking capacity, etc.) and the link with a firm’s performance . As control variables, we took information relative to companies (age, industry, the size, value added), employees (age, sex, level of education, professional experience), business environment (state of corruption, opportunities, and competition), technological innovations, use of ITC, and production stock. The RGE survey covers the entire country by targeting all economic units spotted on the field. We focused our interest only on SMMEs operating in professional fixed and permanent locations. From the 93,969 companies and institutions surveyed, we extracted 36,976 that integrated our study requirements. The classification used here is that of the National Institute of Statistics (INS 2009), which considers businesses with not more than five employees and a turnover less than US$ 27,275 as micro-businesses; small businesses are companies with the number of employees between six and 20 and a turnover of between US$ 27,275 and US$ 180,820; and medium-sized enterprises are companies with between 21 and 100 employees and a turnover between US$ 180,820 and US$ 1,818,182.

3.2 Specification of the Econometric Model

To estimate the performance of firm i, one can postulate a relation binding its gross margin Y i to its inputs, K i , capital, and L i , labor (see for example King and Park 2004).

where factor θ i collects the productivity of the company.

By supposing a functional form of the Cobb–Douglas equation type, we can therefore obtain a log linear relation as:

The measurement of the performance used in this study can be the sales turnover, the profit or the added value. Each measurement integrates at least one of three shutters: the quantity and the set of market products, selling prices of goods and the cost of acquisition of goods. Each of these shutters can be affected by characteristics of the entrepreneur , characteristics of the company, and related commercial practices. In this analysis, we consider two main inputs: the capital which we approximate by investments carried out by a company since its creation. The second component is the labor factor which includes the total number of permanent and temporary workers, which is a fraction of the annual total number of working hours carried out by permanent and temporary employees.

Productivity θ i is unobservable by the econometer. We make the assumption that this depends on the characteristics of an entrepreneur (like Paulson et al. 2006) and on the characteristics of a company and the market (see King and Park 2004). Based on this clarification, we suppose that productivity depends, beyond the business climate, on the intrinsic characteristics of an entrepreneur. We can thus express the logarithm of productivity θ i of company i as:

where X i is a vector of variables controlling characteristics specific to an entrepreneur such as the level of education , experience, gender, age, and social networking abilities and mainly takes into account his/her managing capacities; Z i is the vector of characteristics specific to the company such as the age, the branch of industry, and the geographical situation; C i is the vector of variables related to environmental factors and the triggering events for an entrepreneur . Ɛ i can be seen like errors of measurement or shocks on the productivity of the company. By combining Eqs. 2.3.2 and 2.3.3, we obtain a reduced form of the model, which can then be written as:

Taking into account the broad variance in the size and type of company, and the heterogeneity of the firm’s activities, the traditional assumption of the constant variance of the stochastic term of error in this model is likely to be violated. We thus suppose heteroscedasticity by expressing the variance of errors like a multiplicative function of all explanatory variables of the model (see, for example, Harvey 1976 or Greene 2003: 232–235). The parameters of the model are estimated by the maximum likelihood method which minimizes the sum of the squares of errors. Given the size of our sample, standard deviations might not be correctly estimated if one uses the asymptotic matrix of variance–covariance.

3.3 Choice of Variables

The development of an entrepreneurial culture in Cameroon relies as much on factors related to the entrepreneurs themselves, their families, their motivations, and the business environment and to the actual location of a company. In the hope that the factors explaining entrepreneurs’ characteristics affect entrepreneurship and thereby boost the performance of SMMEs, we describe the variables related to the characteristics of an entrepreneur, variables related to triggering events for an entrepreneur, and variables related to the environmental factors of an entrepreneur (Table 2.1).

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive Statistics and an Econometric Estimation of the Model

Table 4.2 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables used in different tests depending on the company size. It shows that more men (60 %) than women (29 %) were entrepreneurs regardless of the type of business. This suggests that gender influences the decision to create a business or not. This is explained by the fact that women in Cameroon spend more time taking care of family issues and domestic tasks. Dominique (2008) shows in his book that 80 % of domestic tasks are done by women who spend 33 h per week on these tasks, against 16.30 h per week spent by men. Cameroonians of all ages create businesses. An analysis by age shows that 80 % of SMME entrepreneurs were less than 50 years. The youngest were eager to become entrepreneurs, but they usually had neither the money nor the experience to do it. In addition, the older may have the capital and experience required, but they have families to support and are reluctant to leave their careers to become entrepreneurs.

Nearly 92 % of the entrepreneurs were Cameroonians and had at least FSLCFootnote 1 (70 %). The nature of training completed was a determining criterion for Cameroonian entrepreneurs’ characteristics : 19 % had no training , 52 % had not received proper training to help them exercise their profession, but rather had opted for ‘learning by doing’ as against 20 % and 9 %, respectively, who had received a diploma in vocational training and continuous education. The latter are more dynamic in business relations and tend to have the knowledge and know-how to run their businesses in a rational and healthy way. They might have multiple business opportunities, especially with the ongoing digital revolution, particularly the further development of ICTs. A new company is based on the knowledge and expertise of its founder and these often depend on the skills acquired by an individual within the incubator organization and on experiences acquired while learning on the job.

Approximately 79 % of the entrepreneurs incubated in individual enterprises (IE), against 4 % of businesses housed in the form of private limited companies (PLCs) and 1 % entrepreneurs who had created anonymous societies (AS). In fact, the legal form of a business is best known as the corporate status of people, not of capital. The low proportion of capital corporations in general and anonymous corporations in particular is due to the fact that anonymous corporations require an opening capital of at least US$ 18,185 and they are usually assessed by an auditor registered in the auditor’s order. Other forms of companies account for just 15 % of all Cameroonian companies. A statistical analysis shows that there is a significant relationship between the gender of an entrepreneur and the company’s performance.

4.2 Econometric Estimation Results

Entrepreneurs act on the basis of the personal interpretations that they make of the strategic situations that they face. These interpretations are based on their experiences, cognitive patterns, values, and behavioral biases. The models clearly express a relationship between an entrepreneur’s characteristics and performance since the null hypothesis of the absence of overall influence of independent variables on the dependent is rejected (use Fisher’s test: Global F test). Even if they explain 22, 12, and 36 % of the variation, respectively, in the performance of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (adjusted R2), the explanatory variables are statistically significant in the regression with p values below 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1, respectively (Table 3.3).

Variables related to capital and labor are significant at a 1 % risk for all types of SMMEs. These results establish that the growth of added value remunerates capital up to 82.74, 26.36, and 34.37 % for micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises , respectively, and labor for about 19, 30 and 74 % for micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises, respectively (Tables 2.2 and 2.3).

4.2.1 Age

Regarding the age of an entrepreneur, the nonsignificance of age for young entrepreneurs (under 30 years) is justified by the fact that the category of companies which features a majority of young entrepreneurs (such as taxis, call boxes, outdoor activities on the shelves, street merchants) is excluded from the sample. Rather, Cameroonian entrepreneurs aged more than 30 have a negative influence (statistically significant at the 1 % level) on a firm’s performance . These results can be explained in two ways: either the entrepreneur has no training or experience in the field and thus fails to adapt to the changing socioeconomic environment leading to decreasing performance, or the rooting of the entrepreneur (family, religion) has a negative influence over time on the company’s performance. These results confirm previous studies on the rooting of an entrepreneur in the business (Jorissen et al. 2002). Yet, one would expect a positive influence given that the entrepreneur has more experience in the market. This may underline the presence of deviations related to the altruism of owner-managers who take decisions alone and may be tempted to take them in order to enrich themselves (excessive private withdrawals), which could be detrimental to the firm’s performance. Our results confirm previous studies that discuss the fact that the company’s owner-manager is enrooted and established over his/her firm (Gallo 1995, for Spanish enterprises; Cromie et al. 1995, for Northern Ireland; and Jorissen et al. 2002, for Flemish companies). There should be more stimuli to incite young entrepreneurs to create more firms and in their performance. Most young entrepreneurs (less than 30 years of age) manage informal and outdoor activities that are not much appreciated. But these young entrepreneurs are highly skilled, well trained (most of them have a degree), easily integrate ICT in their daily practice, and are oriented toward innovations. But most of them have difficulties in obtaining funds from creditors to launch their own start-ups given market uncertainties and lack of credibility that they show due to their inexperience and a lack of tangible assets that could serve as safeguards in the eyes of creditors (their liquidation value being important). The Cameroon government should therefore help younger entrepreneurs in launching and developing start-ups by tutoring their projects and assisting them in obtaining financial means for their projects.

4.2.2 Gender

In terms of gender, the sex of an entrepreneur negatively influences (statistically significant at 5 %) the performance of very small businesses . This result suggests that there is a gender-biased, heterogeneous distribution of entrepreneurial opportunities. This can at least partly explain the fact that in Cameroon only a few women are embarking on entrepreneurial careers. Even when they start their own businesses (often within the informal sectors), they have to deal with the local culture which posits that women should stay in their marital home. This result is consistent with earlier research proposing that societal expectations restrict women’s entrepreneurial activities. In the context of Cameroon , the weak participation of women in entrepreneurship can be explained by a complex combination of reasons such as (frequent) maternity, lack of motivation (for example, as a result of societal expectations and pressure, as well as a lack of inspiring role models), and the absence of entrepreneurial training . All these hinder the creation of firms on the one side and the development of women’s entrepreneurship on the other.

The negative performance impact of women can also be partly explained by the relationship that a female entrepreneur might have with other employees at the job which is linked to gender roles ascribed by society. As gender roles in Cameroon do not encourage women heading men, female leaders can make the (male) working environment hostile and sometimes aggressive toward them. This may even lead to a conscious sabotage of a firm’s performance by some employees in order to get rid of a female manager. The Cameroon government has put in place different initiatives to encourage women to embark on entrepreneurial activities through entrepreneurial capacity-building training for different women’s groups in urban and rural areas in various domains (agriculture, buying and selling, sewing, etc.). These types of initiatives should be extended to other activities given the high demand for entrepreneurial capacity building, but they also need to focus on changing the societal image of women as entrepreneurs, for example, by promoting successful women as inspiring role models. In addition, networking between women entrepreneurs should be encouraged to provide a platform for like-minded individuals and for reducing negative feelings such as envy between women.

4.2.3 Training Perspective

Reflecting the cognitive bases of entrepreneurs, training acts just like other idiosyncrasies on their perceptions and interpretations of the situations that they face. Our study shows that vocational training has a positive influence on the performance of SMMEs. This positive effect is statistically significant at a 1 % threshold for small businesses. Vocational training, while determining career opportunities and the mileage of entrepreneurs, allows business value creation and managerial rents. This type of technical and vocational education allows acquiring immediate employable skills in the labor market. Considering that the Cameroonian education system allows continuous and vocational training , it is likely that entrepreneurs with training are more pragmatic and take better decisions than those who were not able to follow the same kind of training. That is, a vocational college promotes better business performance than continued training. Although it is not possible to prove a causal relationship in this study, training seems to be an accelerator in performance as confirmed by the new education system in Cameroon (LMD system). The influence of entrepreneurs’ vocational training appears to be a source of competitive advantage, mainly residing in the managerial human capital as scarce resource, which is imperfectly imitable by competitors. In effect, this reflects the new orientation being followed by Cameroon’s higher institutions with the LMD system, focusing more on training (professional) and lowering the place occupied by general training. In fact, the latter favored unemployment and unskilled employment. It is important to note that from 2000 onward, with a multiplication of professional training schools in engineering, Cameroon’s education system is emphasizing the development of entrepreneurial characteristics and the intent of enterprise through focused programs and curricula. The new system develops entrepreneurial characteristics in learners and leads to an expression of enterprising intents. It also focuses on stimulating entrepreneurial skills (anticipation, creativity, strategic planning, and initiative to take charge). Our result is consistent with that of Castanias and Helfat (2001) according to whom the business performance of entrepreneurs who have professional training is higher than that of those with continued training. Thus, public and private training institutions should expand vocational training relating to the job market.

Learning in a work situation allows acquiring knowledge that plays a key role in managing new situations, but it has a nonsignificant positive effect on the performance of micro- and medium-sized enterprises and a nonsignificant negative effect on the performance of small firms. This nonsignificance justifies the ease of integration and accumulation of knowledge that entrepreneurs acquire informally. Entrepreneurs with no formal education have a positive influence (statistically significant at the 1 % level) on the performance of micro-firms. This result is justified by the fact that the micro-firm sector excels at socio-professional integration of young people animated by the spirit of enterprise, that is, becoming entrepreneurially active out of a necessity of being unemployed.

4.2.4 Education

The education levels of an entrepreneur play a key role in increasing a firm’s productivity. The statistical nonsignificance of primary education in our results can be explained by the fact that entrepreneurs who have acquired basic knowledge only (that is, reading, writing and counting) lack the ability to adapt easily to changes related to a restless socioeconomic environment and this is a major handicap for the productivity of their businesses. This low level of education might be one of the main reasons for bad management (or inexperienced management) of owner-managers and bankruptcy of (small) businesses in Cameroon . Entrepreneurs with higher levels of education (of the second cycle) positively influence (statistically significant at the 1 % for small and 10 % for medium-sized firms) firms’ performance. This is because the higher education system provides training of the mind that makes adopting knowledge and new technologies easier, which are sources of productivity growth. Study levels of entrepreneurs are thus a factor of persistent entrepreneurial logic that maintains an individual in a process of creative change.

Entrepreneurs are becoming more educated. The Cameroon National Employment Fund (NEF) directs most of its funding to projects headed by entrepreneurs having at least Advance Level Certificate of Education (GCE A level). Among different eligible criteria, an entrepreneur searching for funds to start or enhance his/her business must present concrete entrepreneurial skills or present an advanced level of education to enter the Graduate Employment Program or the Micro-Enterprise Sponsorship Program (NEF Promote Expo leaflet 2014). This points out the importance of education among an entrepreneur’s characteristics in Cameroon’s context .

4.2.5 Social Networking

Concerning social networking abilities, a Cameroonian entrepreneur’s entry into a business group positively influences (significant at the 1 % for micro- and small-, and 5 % for medium-sized firms) the performance of SMMEs. This strong statistical significance is explained by the fact that social networks are a valuable resource for doing business. These networks facilitate economic action and allow entrepreneurs to expand their scope, to save resources, and to access exclusive resources and opportunities. By his/her social capital, an entrepreneur leverages financial resources (such as cash and credit lines) and human resources (such as skills, legitimacy, experience, and know-how) to the business. Through contacts with friends, colleagues, and customers, opportunities emerge to transform network resources into better performance . This result confirms the central proposition of the theory of social capital which stipulates that social networks facilitate economic action (Aldrich and Davis 2000; Burt 1992; Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). Thus, in addition to established institutional networks (such as the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Chamber of Trades and Crafts, and trade unions), a Cameroonian entrepreneur can turn to various firm support networks (GICAM, ECAM, GIC, etc.) to benefit from the externalities provided by government supported structures or develop any type of network ties capable of allowing him/her to transform resources (human, financial, information, advice, etc.) into profit. Also, maintaining good relations with public authorities in Cameroon can promote businesses in the sense that they can ease access to bank credits, position the business in a lower tax regime, and allow a firm to access certain ‘favors’ through social influence. Similarly, joining an informal social group in Cameroon (based on ethnic solidarity or extension of family solidarity) plays a key role in the development of SMMEs, as this group could form a bulk of customers for a company and provide a labor source for the owner of a small business.

4.2.6 Nationality

The nationality of an entrepreneur does not seem to influence his/her behavior to any great degree because a majority of the firms headed by expatriates are multinationals or subsidiaries of international companies. Regarding sectors of activity, the commercial sector and the transport and services sectors have a positive influence (statistically significant at the 1 and 5 % levels) on the performance of micro- and small enterprises. In these profitable and growing industries, the performance of SMMEs in Cameroon tends to increase.

5 Conclusions

This chapter set out to map entrepreneurial characteristics and performance of SMMEs in Cameroon. An entrepreneur’s characteristics as presented in literature are an important factor in performance to the extent that creating a firm requires a coherent management of various parameters. Also, an entrepreneur is at the origin of the idea of creation. Our study sought to demonstrate empirically the relationship between entrepreneurial characteristics and performances of SMMEs. The performance of these companies depends not only on their strategies or the quality of their products, but also on the characteristics of entrepreneurs. Some of the other factors which influence an entrepreneur’s performance in terms of major variables and dimensions include his/her professional training, level of education, sex, age, a strategic partnership-oriented approach, and knowledge of the business environment. These features require access to rich information, to sufficient funding , and to ICT skills and the ability of entrepreneurs to seize the opportunities necessary for better functioning of their businesses.

Existing literature lacks research on the role that the characteristics of an entrepreneur play in Cameroon, while Cameroonian SMMEs are facing intense competition in the both local and international markets. This chapter aimed to fill this gap in research. To increase the robustness of our mapping of entrepreneurial characteristics, they were measured with indicators recommended by Cooper (1982). Our econometric results confirm that in Cameroon if an entrepreneur belongs to a social network, it influences his/her performance in that it facilitates economic action and enables entrepreneurs to expand their scope, save their means, and access exclusive resources and opportunities. An entrepreneur brings financial resources (cash, credit lines) and human resources (skills, charisma and intelligence, skills acquired through experience, and education) to his/her business and leverages network links for further access to resources. In addition, the training followed by an entrepreneur strongly influences his/her firm’s performance in that it provides career opportunities. The type of course of study that an entrepreneur has done leads to the creation of business values and managerial rents. This permits an entrepreneur to acquire skills that are immediately employable in the labor market. Entrepreneurs with professional training are more pragmatic and take better decisions than those who have not been able to follow the same training path. Thus, public and private training institutions should expand vocational training related to the job market. Such orientation is currently being taken up by Cameroonian higher institutions with the LMD system, focusing more on professional training and lowering the place occupied by general training.

An entrepreneur’s nationality does not seem to influence his/her behavior, but age appears to have an effect on performance. Contrary to prior research, we find that the higher age of a Cameroonian entrepreneur (over 30 years) adversely affects the performance of his/her firm. Older entrepreneurs are altruistic, take decisions alone, and make excessive private withdrawals, which could be detrimental to a firm’s performance. Thus, there should be more stimuli for younger entrepreneurs to create firms and also be more involved in their performance. Most young entrepreneurs are highly skilled, well trained (most of them have a degree), easily integrate ICT in their daily practices, and are oriented toward innovation. But many of them have difficulties in obtaining funds from creditors to launch their start-ups given market uncertainties and their lack of legitimacy. This is due to their inexperience and a lack of tangible assets that could serve as safeguards in the eyes of creditors (their liquidation value being important) and facilitate SMMEs’ access to bank credit. Thus, the Cameroon government should help younger entrepreneurs in start-ups and venture development by tutoring their projects and assisting them in obtaining financial means for their projects. This is being done by the National Employment Fund through the Integrated Information Center for Youth Entrepreneurship and its 12 programs integrated in the Pact for Youth Employment (PYE). But these steps are very limited when taking into account the high demand for training and orientation in job creation and entrepreneurship. More efforts should be made and youth-oriented policies formed in order to reach a large number of potential entrepreneurs.

Notes

- 1.

FSLC: First School Leaving Certificate is the very first certificate obtained after completing primary and elementary education.

References

Admassu T (2009) Quelles perspectives de financement pour les PME en Afrique? La revue de PROPARCO

Aldrich H, Davis A (2000) The organizational advantage? Social capital, gender, and access to resources. http://www.unc.edu/~healdric/workpapers/wp132.pdf. Accessed Sept 2011

Aldrich H, Dubini P (1991) Personal and extended networks are central to the entrepreneurial process. J Bus Venturing 6:305–313

Aldrich H, Rosen B, Woodward W (1987) The impact of social networks on business foundings and profit: a longitudinal study. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Babson Collège, pp. 154–168

Alizadeh Y (2000) Unravelling small business owner/manager’s networking activities. http://www.sbaer.uca.edu/research/2000/icsb/pt1/056ali.pdf. Accessed Sept 2001

Allemand I, Schatt A (2010) Quelle est la performance à long terme des entreprises dirigées par les élites? Le cas français. Cahier du FARGO n° 1100604, Juin 2010

Ananga Onana Anaclet, Bikay Bi Batoum Joseph, Wanda Robert, « Les déterminants de la compétitivité des franchises internationales : une analyse empirique du cas du Cameroun. », Revue Congolaise de Gestion 2/2013 (Numéro 18), pp. 9–44

Baron DP (2007) Corporate social responsibility and social entrepreneurship. J Econ Manag Strat 16(3):683–717

Batjargal B (2001) Social capital and entrepreneurial performance in Russia: a panel study. http://eres.bus.umich.edu/docs/workpap-dav/wp352.pdf. Accessed 22 Oct 2001

Becker G (1964) Human capital, a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. NBER-Columbia University Press

Burt R (1992) Structural holes, the social structure of competition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Burt RS (2000) The network structure of social capital. Res Organ Behav 22:345–423

Capiez A, Hernandez EM (1998) Vers un modèle d’émergence de la petite enterprise. Revue Internationale PME 11(4):11–43

Castanias RP, Helfat CE (2001) The managerial rents model: theory and empirical analysis. J Manag 27:661–678

Chabaud D, Estay C, Louart P (2008) Editorial. Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat 7(1):I–XVIII

Chabaud D, Messeghem K, Sammut S (2010) L’accompagnement entrepreneurial ou l’émergence d’un nouveau champ de recherche. Gestion n° 3

Cooper RG (1979) The dimensions of industrial new product success and failure. J Market 43(3):93–103

Cooper AC (1982) The entrepreneurship-small business interface. In: Kent CA, Sexton DL, Vesper KH (eds) Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NY, pp 193–208

Cooper AC (1993) Challenges in predicting new firm performance. J Bus Ventur 8:241–253

Cromie S, Stephenson B, Monteith D (1995) The management of family firms: an empirical investigation. Int Small Bus J 13(4):11–34

Davidsson P (2002) What entrepreneurship research can do for business and policy practice. Int J Entrep Educ 1(1):1–20

Dominique M (2008) Le temps des femmes. Pour un nouveau partage des rôles. Coll. Essais, éd. Flammarion, 199 p

Gallo M (1995) The role of family business and its distinctive characteristic behavior in industrial activity. Family Bus Rev 8(2):83–97

Gartner WB, Starr JA, Bhat S (1999) Predicting new venture survival: an analysis of “anatomy of a start-up”. “Cases from Inc magazine. J Bus Ventur 14(2):215–235

Gauzente C (2011) Mesurer la performance des entreprises en l’absence d’indicateurs objectifs: quelle validité? Analyse de la pertinence de certains indicateurs. Université d’Angers. Finance Contrôle Stratégie 3(2):145–165

Greene William H (2003) Econometric Analysis, 4th edn. Pearson Education Inc., Prentice Hall

Hambrick DC (2007) Upper echelons theory: an update. Acad Manag Rev 32:334–343

Harvey AC (1976) Estimating regression models with multiplicative heteroscedasticity. Econometrica 44(3):461–465

INS (2009) Rapport général sur le recensement des entreprises au Cameroun, Institut national de la statistique

Jorissen A, Laveren E, Martens R, Reheul AM (2002) Differences between family and nonfamily firms: the impact of different research samples with increasing elimination of demographic sample differences. In: Conference proceedings, RENT XVI, 16th workshop, 21–22 November, Barcelona

Julien PA, Marchesnay M (1988) La petite enterprise: principes d’économie et de gestion. Vuibert, Paris

Kamdem ES (2011) Accompagnement des entrepreneurs: genre et performance des très petites et petites entreprises en phase de démarrage dans les villes de Douala et Yaoundé (Cameroun). Edition du Codesia

King RP, Park TA (2004) Modeling productivity in supermarket operations. J Food Distrib Res 35(2):42–55

Lacasse RM (1990) La petite entreprise au canada: le cas particulier de l’entrepreneuriat feminin dans le secteur manufacturier. Thèse de doctorat en Sciences de gestion

Lin N, Dumin M (1986) Access to occupations through social ties. Social Netw 8:365–385

Lorrain J, Belley A, Dussault (2002) Les compétences des entrepreneurs. 4ème Congrès International Francophone sur la PME Université de Metz-Université de Nancy. http://www.airepme.univ-metz.fr/comm/lorbeldu.pdf. Accessed March 2005

Marvel MR, Griffin A, Hebda J, Vojak B (2007) Examining the technical corporate entrepreneurs’ motivation: voices from the field. Entrep Theory Pract 31(5):753–768

Mizruchi MS (1996) What do interlocks do? An analysis, critique, and assessment of research on interlocking directorates. Annu Rev Sociol 22:271–298

Morris MH (1998) Entrepreneurial intensity: sustainable advantages for individuals, organizations and societies. West port, ct: Quorum

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad Manag Rev 23:242–266

Neergaard H, Madsen H (2004) Knowledge Intensive Entrepreneurship in a social capital perspective. J Enterp Culture 12 105(02)

OECD (2001) Encourager les jeunes à entreprendre. OECD, Paris

OECD (2006) OECD Annual Report

Ondel’ansek K (2010) Les contraintes de financement des PME en Afrique: le rôle des registres de crédit. Thèse de Doctorat, HEC Montreal

Paulson AL, Townsend RM, Karaivanov A (2006) Distinguishing limited liability from moral hazard in a model of entrepreneurship. J Polit Econ 114(1):100–144

Plociniczak S (2001) La coordination des relations inter-organisationnelles: une approche dynamique en termes de réseaux. 8ème journée du CLERSE. http://www.helsinki.fi/~jengestr/papers/sizing-up-social-capital/sizing-up-social-capital/htm. Accessed Sept 2002

Quiles JJ (1997) Schumpeter et l’évolution économique: circuit, entrepreneur, capitalisme. Nathan, Paris

Schumpeter JA (1935) The analysis of economic change. Rev Econ Stat 17(4):2–10

Schumpeter JA (1939) Business cycles: a theoretical, historical and statistical analysis of the capitalist process. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 461 pp

Smallbone D (1990) Success and failure in new business start-ups. Int Small Bus J 8(2):34–35

Van Beest F, Braam G, Boelens S (2009) Quality of financial reporting: measuring qualitative characteristics. NiCE Working Paper 09-108

Wright M, Hmeleski MK, Siegel DS, Ensley MD (2007) The role of human capital in technological entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Practice 31(6):791–812

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Tsambou, A.D., 1er Ndokang Esone, L. (2016). Cameroon: Characteristics of Entrepreneurs and SMME Performance. In: Achtenhagen, L., Brundin, E. (eds) Entrepreneurship and SME Management Across Africa. Frontiers in African Business Research. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1727-8_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1727-8_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-1725-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-1727-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)