Abstract

Indonesia is one of the most diverse and multicultural countries in the world. The country’s two presidential regimes between 1945 and 1998, however, forbade the use of ethnicity in censuses, as part of an attempt to develop a common national identity. This chapter provides a historical overview of numerous ethnolinguistic groups in the country using data from the 1930 census. These data are subsequently compared with data from the 2000 census to examine changes in the size of the major ethnolinguistic groups. The analysis shows that variations across groups in fertility and geographic mobility account for differences in growth across the groups during the 70-year period. Furthermore, the chapter focuses on the complexity of conflicts that exist among ethnolinguistic groups. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the important role that ethnicity will play as Indonesia is potentially entering a new era of increasing economic prosperity.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Indonesia is the fourth largest country in the world and is also one of the most multicultural of nations as Hildred Geertz (1963, 24) summarises:

There are over three hundred different ethnic groups in Indonesia, each with its own cultural identity, and more than two hundred and fifty distinct languages are spoken … nearly all the important world religions are represented, in addition to a wide range of indigenous ones.

Within ethnic groups, too, Indonesians have loyalties to kinship, regional and local groupings and frequently their behaviour is influenced by group norms formalised into a body of customary law (adat). Such groupings are of significance when studying demographic behaviour.

One of the major tasks which has confronted successive Indonesian governments since gaining Independence from the Dutch in 1945 has been to overcome the divisiveness of this diversity. The national motto of ‘unity in diversity’ captures this imperative. Some of the greatest challenges faced by Indonesia has been conflicts which have had a significant ethnic dimension. This chapter seeks to analyse the changing nature of diversity in Indonesia, some of the challenges it has presented and examine some of its demographic implications.

The Indonesian Context

Indonesia’s cultural and ethnic diversity is matched by enormous geographical diversity. It is an archipelago of more than 13,000 islands extending over 40° of latitude. A contrast is frequently drawn between ‘inner’ Indonesia (the islands of Java, Madura and Bali) and ‘outer’ Indonesia (Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, West Papua and many other smaller islands). The dichotomy is usually expressed in terms of an uneven distribution of the population with 59.1 % in 2010Footnote 1 living in Inner Indonesia which had only 6.9 % of the national land area. In inner Indonesia rural population densities exceed 500 persons per square kilometre, more than five times the density in the Outer Islands. Indonesia’s ‘uneven’ distribution of population largely reflects geographical differences in soil quality, rainfall and the capacity of the land to support sustained intensive cultivation. Population is concentrated in a number of favourable ‘ecological niches’, especially coastal plains, alluvial valleys and volcanic slopes (Williams and Guest 2012).

Indonesia has experienced a significant structural change in its economy. At the time of Independence, Indonesia was emphatically a rural, geographical country. Even by 1971, only 17.2 % of Indonesians lived in towns and cities and 67.2 % of workers were engaged in agriculture. However, the subsequent four decades have seen significant economic development and social change. By the 2010 population census 49.8 % of Indonesians were enumerated in urban areas and only 40.5 % worked in agriculture. Although there have been fluctuations, there has been significant economic growth in most years with a growth of 6.1 % in 2010. There has been a significant reduction in the proportion of the population living in poverty although Indonesia remains within the ranks, albeit in the upper echelons, of low income countries.

Some Data Issues

The importance of the ethnic dimension in Indonesia was recognised at the last colonial census undertaken by the Dutch in 1930. This high quality census (Volkstelling 1933–1936) included a question on ethnicity and it still provides the most comprehensive picture of Indonesian cultural diversity since it adopted detailed coding by ethnic group and information down to subdistrict level.

Although ethnicity is one of the most salient population dimensions in Indonesia it was not until the 2000 Census of Population that a question was included which sought to capture this characteristic. The potential divisiveness of ethnic identity in Indonesia was such that the regimes of President Soekarno (1945–1968) and Suharto (1968–1998) forbade the inclusion of an ethnicity question in the 1961, 1971, 1980 and 1990 censuses. This decision was influenced in the early years of Independence by a number of ethnic and religious based rebellions as is demonstrated in a later section.

There was some relaxation of concern with the divisiveness of ethnic diversity in the 1980 population census when a question on language spoken at home was included. However, by that time efforts by the government to encourage the use of Bahasa Indonesia saw 11.9 % of the population reporting speaking Indonesian at home. Indonesian is a lingua franca which developed as a trading language throughout the Malay archipelago. Indonesia’s post-Independence encouraged its use to encourage unity and reduce identity with separate ethnolinguistic groups. They gradually introduced it into schools where local languages were previously used, especially in the early years. Nevertheless, the formal and informal sensitivity regarding the Chinese in Indonesia is reflected in the fact that no separate language category was allocated to them at the 1980 census.

In 2000, however, for the first time in the post-Independence period a question on sukubangsa (ethnic group) was asked. Suryadinata et al. (2003, 6) have made a thorough analysis of that data and point out that there is no explicit definition of sukubangsa in the census questionnaire and that respondents were asked to self-identify as belonging to a particular ethnic group. They argue, however, that this may not always be the real ethnic identity of the individual (Suryadinanta et al. 2003, 9). It is complicated by intermarriage between ethnic groups which is very common in contemporary Indonesia but also has a ‘situational’ dimension where some groups, especially the Arabs and Chinese, may report the dominant ethnicity in the area where they are living. This is reflected in the fact that at the 2000 census only 0.86 % of the population (1.74 million) self-identified as ethnic Chinese although most commentators suggest that the Chinese make up between 2 and 3 % of Indonesia’s population (Coppel 1980, 792). Accordingly, as is the case in most countries, the responses to questions on ancestry and ethnicity need to be interpreted with caution.

At the time of writing the 2010 census had been completed and much of the data published, however that on sukubangsa had not been released. This reflects the sensitivity of such information in Indonesia. The results were being checked with a large number of potential and actual stakeholders who could respond negatively to the findings. This is an indication of the fact that even after 65 years of Independence, concern about the potential divisiveness of ethnicity remains.

Indonesia’s Ethnolinguistic Mosaic in 1930

The first time that a question on ethnicity was included in an Indonesian census was in the colonial Dutch East Indies enumeration of 1930 (Volkstelling 1933–1936, 36) and this has been used here to construct an ethnic map of Indonesia at the time. The cultural diversity is reflected in the complexity of this map; indeed, it has been necessary to construct two maps to indicate the distribution of the major ethnolinguistic groups by province. In the maps, the dark circle represents the size of the total population and the shaded wedges indicate the proportions of that population made up of particular ethnic groups. The problems of vast differences in total numbers has meant that, in provinces with comparatively small populations, a light, larger, standard-sized circle was superimposed to effectively show the proportional representation of each ethnic group.

The first map (Fig. 13.1) shows the distribution of the dominant Java-origin groups. In 1930, 47 % of the indigenous population were ethnic Javanese. Figure 13.1 shows their dominance in their central Java heartland and in East Java. Significant numbers have moved into the eastern and northern parts of West Java, to the plantation areas on the northeast coast of Sumatra as ‘contract coolies’ in the first three decades of this century, and in the land settlement areas of southern Sumatra. Post-Independence transmigration programs and transfer of government employees have increased the representation of Javanese outside Java and in Jakarta, but the broad pattern depicted in the map still generally holds.

Indonesia: distribution of java-origin and foreign ethnic groups, 1930 (Source: Hugo et al. 1987, 19). Note: In this map the dark circles are proportional to the size of the population of provinces. Where these are very small, a standard-sized light-edged circle has been superimposed and this circle has been divided up to show the proportional representation of the various ethnic groups

The second largest ethnolinguistic group are the Sundanese (14.5 % in 1930) who are largely confined to their West Java heartland with small numbers in Central Java and South Sumatra. Again it is striking that a significant number of Sumatran residents are Sundanese due to colonial migration. The third largest ethnic group, the Madurese (7.3 %), have spread out from their small island home area to settle in East Java. In 1930, some 11.7 % of indigenous residents were reported as being ‘Batavians’. This group, now referred to as the ‘Jakarta Asli’ or ‘Betawi’, emerged as a distinct ethnolinguistic group during the colonial period through the intermarriage in Jakarta (then called Batavia) of indigenous groups (especially Balinese) with Chinese, Arabs and Europeans. They are confined mainly to Java in and near Jakarta. The Balinese in 1930 were concentrated almost entirely on Bali and Lombok (in Fig. 13.1 Sassaks from Lombok are included with the Balinese).

Figure 13.1 also shows the distribution of non-indigenous groups in 1930, of which the Chinese were, and still are, the most significant. Ethnic Chinese make up around 2–3 % of Indonesia’s population (Coppel 1980, 792), although their dominance in some sectors of the economy is perceived by some to give them a significance out of proportion to their numbers. The map shows that, in 1930, the Chinese were significantly represented in most areas, mainly in the urban sectors of those provinces. However, they were especially strong proportionately in areas where they had been brought in by the Dutch to work as coolies on plantations and in mines (northern and eastern Sumatra and West Kalimantan).

Figure 13.2 shows the distribution of the major outer island-origin groups recognised at the 1930 census. The situation here is much more complex than in Java since there are many small groups which have their own distinctive language and culture. In 1930, 71 % of Indonesians belonged to Java-origin groups. The largest single outer island group was the Minangkabau (3.4 % of all indigenous people) whose heartland is West Sumatra, but whose peripatetic nature has ensured that they have spread widely throughout the archipelago. They have spread widely through Sumatra and make up the largest single Sumatran-origin group. The Bataks comprise a number of distinct groups which together, in 1930, accounted for 2 % of the native population. Their concentration in North Sumatra is readily apparent in Fig. 13.2. Another significant group are the ‘coastal Malays’ who make up 7.5 % of the total indigenous population in 1930, but who comprise a number of subgroups. Their distribution along the east coast of Sumatra and the Kalimantan coast is evident.

Indonesia: distribution of outer island-origin ethnic groups, 1930 (Source: Hugo et al. 1987, 23). Note: In this map the dark circles are proportional to the size of the population of provinces. Where these are very small, a standard-sized light-edged circle has been superimposed and this circle has been divided up to show the proportional representation of the various ethnic groups

Figure 13.2 shows that, in Kalimantan in 1930, three indigenous groups dominated – the coastal Malays referred to above, the Dayaks (1.1 % of the total) who lived in the interior, and the Banjarese of the southern coastal area. The Banjarese made up 1.5 % of the total indigenous population in 1930.

In Sulawesi, the southern half is dominated by the Bugis who make up 2.6 % of the total Indonesian indigenous population in 1930. In South Sulawesi, however, there are also other distinct and significant ethnic groups like the Makassarese (1.1 % in 1930), Torajanese (0.9 % in 1930) and Mandarese (0.3 %) and these – together with the Minahassans who dominate the northern part of the island (0.9 % in 1930) – are the largest ethnic groups in Sulawesi. Figure 13.2 shows that, in the remaining islands, the largest groups are the Moluccans, Timorese and Papuans, although a host of other (albeit smaller) distinct ethnic groups live in those areas. In eastern Indonesia, there are groups who are ethnically and culturally much more similar to the Melanesian groups further east than to the Malay groups in the rest of Indonesia.

In pre-Independence, and indeed the Indonesia of the 1950s and 1960s, each area of the nation was overwhelmingly dominated by particular ethnolinguistic groups – the Sundanese in West Java, Javanese in Central Java and East Java, Minahassans in North Sulawesi, Batak groups in North Sumatra, Banjarese in South Kalimantan, the BBM (Bugis-Butonese-Makassarese) in South Sulawesi, Minangkabau in West Sumatra, among others. This is evident in the ethnic data collected at the 1930 census (Hugo et al. 1987, 18–24). Only in Jakarta was there substantial mixing of the ethnolinguistic groups as Castles (1967, 153) points out:

… it is paradoxically the most – even the only – Indonesian city … (the) metaphor of the melting pot comes to mind – into the crucible, Sundanese, Javanese, Chinese and Batak: God is making the Indonesian.

In other provinces particular ethnolinguistic groups dominated, and this continued in the early years of Independence.

Processes of Change

Before examining the contemporary ethnic profile of Indonesia it is important to briefly mention some of the processes which have impinged upon the picture presented in the previous section. Intermarriage between ethnic groups has been a feature of post-Independence Indonesia where greater personal mobility has resulted in increased migration and travel beyond the ethnic heartlands evident in Figs. 13.1 and 13.2. However, Suryadinata et al. (2003, 6) argue that:

Even if the person has a multiple ethnic identity, there is always a major or dominant ethnic identity.

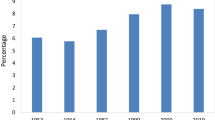

Another difference relates to fertility. The growth of an ethnic group since 1930 will be influenced by the fertility rate of women in that group. While there are no data on the fertility levels of different sukubangsa in Indonesia, there are significant variations between provinces and since several provinces represent the heartlands of particular ethnic groups these data give some useful indications. Figure 13.3 shows the Total Fertility Rates of provinces in 2007 and some striking differences are apparent. Provinces in which the Javanese, Madurese and Balinese are dominant have very low fertility levels and this has been a consistent pattern over a long period (Hugo et al. 1987). On the other hand several Outer Island provinces have, in East Indonesia and North Sumatra, significantly higher fertility levels reflecting higher rates of fertility among such groups as the Batak in North Sumatra and several Sulawesi, East Nusatenggara and Papua based ethnic groups.

Indonesia: total fertility rate by province (Source: Statistics Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik – BPS) and Macro International 2008, 50)

Just as there are differences between ethnic groups in fertility, there are differences in their propensity to move. Ethnographic studies have shown that migration has become institutionalised within some ethnic groups in Indonesia, such that it has become the norm for particular people within those groups to spend at least part of their life span outside their village of birth. This explanation has been particularly invoked in the case of the highly peripatetic Minangkabau people of West Sumatra (Naim 1973; Murad 1980).

Similar sociocultural influences have been observed to be a factor in causing high levels of population mobility among several other ethnic groups, including the Acehnese (Siegel 1969) and several Batak groups from the northern part of Sumatra (Bruner 1972), the Rotinese people of East Nusatenggara (Fox 1977, 56), the Banjarese of South Kalimantan (Rambe 1977, 25) and the Bugis of South Sulawesi (Lineton 1975, 190–191). The institutionalisation of migration operates in Indonesia, not only at the scale of the ethnic group but also on regional and local levels. Naim (1979) examined 1930 and 1961 census data to produce a typology of ethnic groups according to their propensity to move and this is shown in Table 13.1.

Increased levels of interprovincial movement in the Suharto era considerably reduced the dominance of single ethnolinguistic groups in individual provinces. This was assisted by a determination of the central government to enhance the feeling of unity across the Indonesian archipelago and downplay the separatist tendencies associated with individual ethnic groups and their cultures. This was evident in such policies as the replacement of local languages with Indonesian as the medium of instruction in schools, the refusal to ask questions on ethnicity in censuses so that the relative size of ethnic groups could not be determined, encouraging the use of the Indonesian language over local languages in all media, government etc. and the exclusive use of the national language in mass media.

The improvement of interprovincial transport (Hugo 1981), the transmigration program (the insertion of Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese and Balinese in Outer Island communities), the transfer of government employees and centralisation of financial, policy making and decision making issues in Jakarta all downplayed the strength of dominant ethnic groups in the provinces. Moreover, the Suharto regime repressed all aspects of ethnicity and religion in what has been referred to as burying them ‘under a rhetoric of forced tolerance’ (Dhume 2001, 56).

The Contemporary Situation

The difference in fertility levels between groups also has influenced their relative representation. The changes which have occurred in the ethnic profile of Indonesia since Independence will be demonstrated here with reference to data derived from the 2000 population census since, as was indicated earlier, the 2010 data had not been released at the time of writing. The 2000 census ethnicity data has been extensively analysed by Suryadinata et al. (2003). Figure 13.4, drawn from this work, compares the ethnic composition of Indonesia at the 1930 and 2000 census enumerations. It is important to note that the 1930 diagram excludes groups like the Chinese, Arabs and Indians who were differentiated from the ‘native’ population by the Dutch colonial regime.

Indonesia: ethnic group compositions, 1930 and 2000 (Source: Suryadinanta et al. 2003, 13)

At the 2000 census, 1,072 separate ethnic groups were coded (Suryadinanta et al. 2003, 10) but information was published only on 101 groups which represented 93.1 % of the total population. Moreover, of these there were 15 groups with more than one million representations making up 84.1 % of the total population.

Comparing the 2000 and 1930 census data it is interesting that the Javanese population proportion, while increasing from 27.8 to 83.9 million, its proportion of the national population fell from 47 to 41.7 %. This reduction may be in part due to the very low fertility over an extended period among the Javanese, at least as it is represented in their heartland in Central Java, Yogyakarta and East Java (Fig. 13.3).

One of the most interesting trends over the 1920–2000 period, however, has been the dispersal of Javanese throughout the archipelago. This was partly associated with the Transmigration Program which has been a consistent feature of Indonesian governments for over one hundred years. This program has relocated around ten million people from Inner Indonesia to Outer Indonesia over the last century with the majority being Javanese. In addition there has been substantial spontaneous migration of Javanese to other islands, often by transfer of government and private employers. Accordingly, Fig. 13.5 shows the distribution of Javanese across Indonesian provinces in 2000. The largest numbers are in the heartland provinces of Central Java (30.3 m) and East Java (27.2 m) where they make up 98 and 78 % of the provincial populations. However, they also make up more than half of the population in the provinces of Yogyakarta (96.8 %), which is also a heartland area, and Lampung (61.9 %). The latter is especially interesting because it was a major destination of transmigrants over much of the twentieth century (Hugo 2012). In fact, 4.1 million of the 6.6 million inhabitants of Lampung are Javanese. There are also large numbers in Jakarta (2.9 million) where they are over a third of the residents and in North Sumatra (3.8 million – 32.6 %) which was a major destination of Javanese to work on rubber plantations going back to colonial times. There is also a large Javanese population in West Java (3.9 m) but they are only 11 % of the total provincial population.

The remaining provinces with large Javanese populations tend to be those targeted in the Transmigration Program – South Sumatra (1.8 m – 27 %), Riau (1.2 m – 25.05 %), East Kalimantan (721,351 – 29.6 %), Jambi (664,931 – 27.6 %), West Kalimantan (341,173 – 9.1 %) and South Sulawesi (212,273 – 2.7 %). In fact, Javanese make up more than 10 % of the resident population in 17 of Indonesia’s 30 provinces. The Javanese are the largest ethnic group in the provinces of Central Java, Jakarta, East Java, Lampung, Bengkulu, Jakarta, East Kalimantan and Banten.

The diffusion of the Javanese throughout the archipelago of Indonesia thus has been an important post-Independence trend in both ethnicity and migration. The second largest ethnic group in Indonesia are the Sundanese whose heartland is in West Java, especially the inner Priangan upland areas (Hugo 1975). They have a different language and culture to the Javanese who are dominant in East and Central Java. Their proportion of the national population increased slightly from 14.5 to 15.4 % between 1920 and 2000 and their numbers more than trebled from 8.6 to 31 million. They grew more rapidly than the Javanese and this is a function of them having higher fertility levels traditionally (Hugo et al. 1987). Figure 13.3 shows that in 2007 the Total Fertility Rate in West Java and Banten was 2.6 slightly more than Central (2.3) and East (2.1) Java. If we were to go back to 1961–1971 the TFR in West Java was 5.5. Fertility was higher among the Sundanese and slower to decline and accounts for the faster growth rate. Some 85 % of all Sundanese in Indonesia live in West Java where they make up 73.7 % of the total population. Most of the rest live in adjoining provinces in Java – Banten (5.9 %), Jakarta (4.1 %) and Central Java (1.9 %). Figure 13.6 shows that there has not been the extent of dispersion outside of Java that has characterised the Javanese with less than 4 % living outside Java and almost half of these (1.88 %) being in the transmigration province of Lampung which is separated from West Java only by the Sunda Strait.

Indonesia: distribution of Sundanese population, 2000 (Source: Drawn from Suryadinata et al. 2004, 38)

The third largest ethnic group was the Malay population which is the largest of the ‘Outer Island’ ethnic groups and is comprised of a number of subgroups (Suryadinata et al. 2004, 41). They made up 3.45 % of the national population and are mainly found in Sumatra, especially South Sumatra. The Madurese whose heartland is on the island of Madura in East Java province are, like the Javanese and Sundanese, an ‘Inner Indonesian’ ethnic group. They had a low rate of growth between 1930 and 2000 increasing from 4.3 to 6.7 million and their proportion of the national population declining from 7.3 to 3.4 %. Like the Javanese they have low levels of fertility. Most Madurese are in East Java (92.8 %) but there has been some diffusion, especially to West Kalimantan where a strong migration connection has developed. Accordingly, 3 % of Indonesia’s Madurese population in 2000 lived in West Kalimantan (203,612) where they made up 5.5 % of the local population. The other provinces of Kalimantan account for 2 % of the Madurese population and there is a large community in Jakarta (47,055).

The fifth largest group are the Bataks whose heartland is in North Sumatra and are made up of a number of subgroups – Karo, Toba, Mandailing, Tapanuli etc. Their numbers increased fivefold between 1930 and 2000 to reach 6.1 million and their share of the national population increased from 2 to 3 %. They are well known as a group with relatively high fertility (Hugo et al. 1987) and this is evident in Fig. 13.3 which shows that North Sumatra has the third highest fertility in Indonesia. The Bataks have been well known (Bruner 1974) as a relatively mobile group and in 2000 slightly more than a fifth lived outside the homeland of North Sumatra where Bataks made up 42 % of the total population. Some 8.8 % are found in the neighbouring provinces of Riau and West Sumatra but they have been an important group moving to Jakarta where 5 % of Bataks live and they make up 3.6 % of the resident population.

The sixth largest group – the Minangkabau – are one of the most interesting (and studied). As indicated earlier, they are well known as the most mobile of Indonesian sukubangsa (Naim 1979). This has been partly associated with the matrilineal inheritance system of the Minangkabau (Murad 1980). The numbers of Minangkabau increased from two million in 1930 to 5.5 million in 2000 but they fell from the fourth to the sixth largest group over this time and their share of the national population from 3.4 to 2.7 %.

The distribution of the Minangkabau population is shown in Fig. 13.7. Their heartland in West Sumatra is immediately apparent but only 68.4 % of the Minangkabau live in this province – the lowest for any of the major ethnic group heartland. This reflects the strong tradition of merantau. However, Fig. 13.7 does not give a full picture of their extent of dispersal across Indonesia and perhaps reflects that those who move do so to the urban centres of the province and the fact that many in fact return to West Sumatra after living for an extended period in another province. They also have traditionally moved in large numbers to neighbouring Malaysia. The diagram shows that the bulk of movement has been to neighbouring provinces in Sumatra and to Western Java, especially Jakarta where they make up more than 3 % of the population.

Indonesia: distribution of the Minangkabau population, 2000 (Source: Drawn from Suryadinata et al. 2004, 54)

The next largest group, accounting for 2.5 % of the population is Betawi that made up 1.7 % in 1920. The Betawi are a group which has evolved from the mixing of a number of Indonesian and foreign groups in Jakarta over several centuries (Castles 1967). The regional growth of the group is undoubtedly associated with the expansion of Jakarta into neighbouring provinces. While only 45.7 % of the Betawi live in Jakarta, another 37.7 % live in West Java and 9.6 % in Banten. This reflects the ‘suburbanisation’ of Jakarta which has seen continuous megalopolis development overspilling the official provincial boundaries so that much of the Jakarta functional urban area is in Banten and West Java provinces (Jones 2004). These three provinces have 98.8 % of the Betawi population.

The Bugis, the fifth largest group in 1930, had fallen to eighth in 2000 although their numbers increased from 1.5 to 5 million. Their distribution is shown in Fig. 13.8 and it will be noted that there is a concentration in the heartland of South Sulawesi. However, only 65.2 % of Bugis live in this province reflecting the peripatetic nature of this group (Lineton 1975). They have been very active in moving to other parts of the archipelago, especially Eastern Indonesia. They have not only moved into other parts of Sulawesi but have been important colonisers in East Kalimantan, Papua and Riau in Sumatra.

Indonesia: distribution of the Buginese population, 2000 (Source: Drawn from Suryadinata et al. 2004, 61)

The Bantenese are the ninth largest group in Indonesia with 4.1 million in 2000 and 2.1 % of the Indonesian population. They are strongly concentrated in the province of Banten in the far west of Java where 92 % live. Most of the rest live in adjoining provinces of Lampung, West Java and Jakarta. They are an interesting group speaking a language which is closer to Javanese than Sundanese and tracing their origins to colonisation by Javanese in the western margins of Java in the sixteenth century. It was invaded by the Islamic Acehnese Faletehan in 1527 who was acting in the name of the sultan of Demak (Central Java). Even today there are linkages with North Sumatra which has the fourth largest Bantenese population in Indonesia.

The Banjarese are the tenth largest ethnic group in Indonesia and the largest within its heartland in Kalimantan. They increased their share of the national population from 1.5 to 1.7 % between 1930 and 2000. Their distribution is shown in Fig. 13.9 and the concentration in Kalimantan, especially South Kalimantan, is apparent. Nevertheless they too traditionally have been one of Indonesia’s most mobile sukubangsa with less than two thirds (65 %) living in South Kalimantan and important communities being established not only elsewhere in Kalimantan but also in East Sumatra (Naim 1973).

Indonesia: distribution of the Banjarese population, 2000 (Source: Drawn from Suryadinata et al. 2004, 67)

The Balinese are the next largest group with 1.5 % of the national population. They are a distinctive group not only because of their own language and rich culture but because most are Hindu. Figure 13.3 shows that Bali has one of the lowest fertility rates of all provinces reflecting the low fertility of the Balinese. Some 92.3 % of the Balinese live on the island of Bali where they account for 88.9 % of the population. There are small but significant numbers of Balinese in Central and Southwest Sulawesi where they moved under transmigration schemes.

The Sasaks in 2000 numbered 2.6 million making up 1.3 % of the national population. They are mainly concentrated in the province of West Nusatenggara, especially on the island of Lombok. The next largest group are the Makassarese (two million) who are concentrated in their heartland in the south of South Sulawesi. They have, like the Bugis who they share their heartland with, been quite mobile in Eastern Indonesia and Malaysia. In fact, the term BBM (Bugis-Butonese-Makassarese) is used to designate the three groups of Sulawesi origins who have become dominant in the informal sector in Eastern Indonesia, especially in urban areas. The Butonese heartland is in Southwest Sulawesi and they numbered 578,231 in 2000 – the 21st largest ethnic group.

The next largest group were the Cirebon sukubangsa. They, like the Bantenese, are a distinct group resident in West Java, in this case the north coastal eastern margins of the province. Their language is close to Javanese and reflects earlier colonisation by the Javanese. They numbered 1.9 million in 2000. They were followed by the Gorontolo from North Sulawesi (974,175), Acehnese from North Sumatra (871,994), Toraja from South Sulawesi (750,828), Nias from Eastern Indonesia (731,620) and Minahassa from North Sulawesi (659,209).

The ethnic Chinese in Indonesia are a significant group but as Suryadinata et al. (2004, 74) point out, there is considerable difficulty in estimating the size of the population because the self identification methodology in the 2000 census would have resulted in significant numbers of those with an ethnic Chinese origin not identifying themselves. There has been a history in post-Independence Indonesia of governments acting to suppress expression of Chinese ethnicity. These have included:

-

During the Sukarno era there was a substantial repatriation of Chinese to China and in some provinces they were restricted to living in urban areas.

-

The Suharto regime adopted an assimilationist policy which banned three pillars of Chinese culture – Chinese organisation, Chinese media and Chinese schools.

-

Chinese were strongly encouraged from the 1960s onward to adopt Indonesian names and discard their Chinese names.

-

There were periodic anti-Chinese riots in cities, most recently in May 1998.

This operated so as to encourage some Chinese to hide their Chineseness so that the number identifying as Chinese in 2000, 1.74 million, is undoubtedly an underestimate.Footnote 2

In 1930 the ethnic Chinese in Indonesia numbered 1.23 million. It is likely that their growth over the 1930–2000 period was slower than for the Indonesian population as a whole. This is due to them having lower fertility than the total Indonesian population but also significant emigration including a repatriation of over 100,000 in 1960 (Hugo et al. 1987). Nevertheless, it is apparent that there has been significant underenumeration of ethnic Chinese. Suryadinata et al. (2004, 78) have produced a number of estimates of the ethnic Chinese population of Indonesia using assumptions about their representation in the 19 provinces for which there is no data available and for the extent of non-identification. These are presented in Table 13.2 and range between the 11 province census figure of 1.74 million up to 6 million. Their best estimate is 2.92 million, representing more than a doubling since 1930.

The 2000 data is only available for the 11 provinces with the largest ethnic Chinese population enumerated at the 2000 census and the numbers are depicted in Fig. 13.10. Recognising that these underestimate the strength of the ethnic Chinese population they show that a quarter of Indonesia’s Chinese population lives in Jakarta where they make up 5.5 % of the population. The second largest group is in West Kalimantan which has long been recognised as having one of Indonesia’s largest Chinese communities (Ward and Ward 1974) and census data indicate about 1 in 10 residents are Chinese. The only larger representation is in Bangka–Belitung in Eastern Sumatra where they make up 11.5 % of the population. In addition the province of Riau has the fourth largest Chinese community in Indonesia. Other large numbers are in Inner Indonesia in East Java, Central Java, Banten and West Java.

Indonesia: distribution of the ethnic Chinese population, 2000 (Source: Drawn from Suryadinata et al. 2004, 81)

Ethnic Related Conflict in Indonesia

The post-colonial era in Southeast Asia has seen significant conflict within and between countries and several of these conflicts have had an ethnic dimension (McNicoll 1968). In Indonesia the first two decades following Independence there were a number of conflicts as the government sought to bring together the many different groups into a single nation. Indeed, the only two things which all groups had in common when the new nation was formed were geographical propensity and a common Dutch colonial heritage. Inevitably the early years of nation building saw conflict between groups, some of which had an ethnic dimension.

The Javanese made up between 50 and 60 % of the new nation’s population and assumed many of the elite positions in the new government. There were a number of challenges to the new government in regions of the nation where the Javanese were not dominant. Figure 13.11 shows the location of the main areas of conflict during the first twenty years of Independence in Indonesia. The forced movements that resulted from this have been discussed in detail elsewhere (McNicoll 1968; Hugo 1975, 1987, 2002; Goantiang 1965; Naim 1973) but the major conflicts were as follows and, as will be seen, several have an ethnic aspect:

Conflicts creating outmigrations in Indonesia, 1950–65 (Source: Hugo 2002, 304)

-

The struggle for Independence from the Dutch saw substantial movements such as the evacuation of virtually the entire Indonesian population (approximately half a million people) from Bandung in 1946–1948 (Hugo 1975, 254). Naim (1973, 135) reported a large scale evacuation in West Sumatra from Dutch occupied coastal areas to the republican areas of the interior. In addition, there was an attempt to set up a Republic of the South Moluccas in Maluku where many were fiercely loyal to the Dutch and indeed several followed their colonial masters back to the Netherlands where they settled and established a strong ‘Free Moluccas’ Movement (Kraak 1957, 350).

-

Religion based conflicts such as Darul Islam in West Java (1948–1962), South/Southeast Sulawesi (1955–1965), Aceh (1953–1957, 1959–1961) and South Kalimantan (1950–1960) aimed at making Indonesia an Islamic state and initiated substantial movement (McNicoll 1968, 43–48; Hugo 1975, 1987; Harvey 1974; Castles 1967, 191). While these rebellions were ostensibly to make Indonesia an Islamic state, they had a strong regional focus and tended to be dominated by particular ethnic groups.

-

Internal ethnic conflicts not related to autonomy/separatist dimensions emerged in the 1960s and earlier. In 1967, some 60,000 ethnic Chinese were forced out of the interior areas of West Kalimantan due to longstanding hostility against the Chinese (Ward and Ward 1974, 28). Similarly, displacement of Chinese occurred in West Java in the 1950s (Hugo 1975, 245).

-

Inter-elite power struggles in the 1950s were marked by the PRRI-Permesta Rebellions in Central Sumatra and North Sulawesi. These struggles were against the authority of Jakarta and were supported mainly by the educated elite. It caused substantial movements, both during the rebellions and after authority was restored (McNicoll 1968, 44; Naim 1973, 139).

-

Ethnic conflicts with autonomy/separatist dimensions such as those in Irian Jaya/West Papua at times initiated refugee flows (Roosman 1980) as did the 1970s conflict in East Timor (1979, 1981) which involved the displacement of about half of the population.

Each of these rebellions was put down and for much of the 1970s and 1980s there was little ethnic related conflict apart from occasional anti-Chinese riots such as occurred in the city of Bandung in 1973. However, the period following the onset of the financial crisis in Indonesia in 1997 and the collapse of the long serving Suharto regime in 1998 saw dramatic political as well as economic and social change. Instability was created by the economic crisis which saw the loss of around three million jobs in urban areas and a devaluation of the currency making many key imported goods very expensive (Hugo 1999). Moreover, Indonesia moved away from several decades of highly centralised and controlled government to a system based on regional autonomy. Since more power and decision making went to the regions and there was less control from the centre, this inflamed any simmering regional tensions between natives and newcomers, different ethnic groups, different economic groups and Muslims and Christians. Nevertheless, such resentments have had more complex origins than simply being due to ethnicity. They have been of long standing in many Outer Island areas and events have been the trigger rather than the underlying causes of conflict. In the first year following the ousting of Suharto there was a substantial displacement of IDPs so that by August 1999 there were around 350,000 (United Nations 2002, 3). However, separatist, inter-ethnic and religious based conflicts resulted in 1,107,193 persons (277,836 households) in 2002 (Hugo 2002).

Figure 13.12 indicates that at the time, 20 of Indonesia’s 26 provinces had people classified as IDPs. While the reasons for that displacement are complex, there was an ethnic element involved in that particular ethnolinguistic groups were influenced more than others. It does not include the several large physical disasters which have displaced large numbers of Indonesians over the last decade like the 2004 tsunami and the Pandang earthquake of 2008. All of the 20 provinces shown in Fig. 13.12 have not experienced conflict but some have become the destination of people displaced from other provinces which have seen conflict. The main sources of IDPs associated with bloodshed have been Aceh, Maluku, East Timor (now the independent nation of Timor Leste), Central Sulawesi, Central Kalimantan, Irian Jaya and West Kalimantan. Some refugees remained in the areas of conflict. Many of those who were displaced were former migrants, or more often, the descendants of former migrants, and some have returned to their areas of origin or usually the case, the origin of their parents or grandparents. Hugo (2002, 308) found that many of these migrants have not retained linkages with their areas of origin so they have not been able to seek refuge in the homes of family members in their origin areas. Accordingly, many were forced to enter government-run camps in their destination province or in their origin areas. The major conflicts are as follows:

Total numbers of IDPs throughout Indonesia (as of 31 March 2002) (Source: Hugo 2002, 307)

-

In Northern Sumatra the Acehnese have been seeking independence from Indonesia from the earliest days of the republic. In the 1950s there was a major campaign to turn Aceh into an independent Islamic state and in 1976 the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) was formed. As the United Nations (2002, 27) points out:

Foremost among grievances has been that the revenues generated by the province’s resources have gone to the Central Government rather than benefiting Aceh, resulting in a slow pace of development. Other issues include the continued presence of the Indonesian Armed Forces (TNI) in the province, the violence against civilians and the GORI (Government of the Republic of Indonesia) shortcomings in bringing to justice the perpetrators of human rights violations.

The post-1998 situation saw several hundred people killed, arbitrary arrest, torture, hundreds of public buildings burned down and more than 200,000 displaced by fighting. The tsunami of 2004 devastated much of the province and displaced many more.

-

In West Kalimantan there has been a history of clashes between local Dyaks (or Dayaks) and Madurese who came from their island home near East Java as official transmigrants or spontaneous settlers throughout the twentieth century. The United Nations (2002, 48) summarised the situation as follows:

Ethnic Madurese families have been migrating to West Kalimantan for the past 100 years in search of economic opportunities. The indigenous ethnic Dyaks and Malays have typically viewed the Madurese as invaders, given their different language, cultural norms and unwillingness to conform with, and participate in, the routine of established society. Misunderstandings and anger between these populations has simmered for decades until the late 1990s when the rage was unleashed, resulting in hundreds of brutal deaths and the displacement of 60,000 Madurese into the capital city of Pontianak.

Similar conflicts have occurred in Central Kalimantan.

-

Maluku in Eastern Indonesia has a history of being a flashpoint. Both the island of Ambon in the south and the northern islands have been subject to violence and movement of displaced persons. There is a long history of conflict between Christians and Muslims in the province including when Christian separatists sought to break away from the new Indonesian republic in 1949. However, for most of the subsequent period there has been a local tradition of pela gambong (non-violence) although over this period consistent inmigration of Muslims from Southern Sulawesi has reduced the Christians’ demographic dominance (McBeth and Djalal 1999). While the conflict in Maluku is usually depicted as a Muslim-Christian conflict, the situation is in fact more complex. As the United Nations (2002, 39) has pointed out:

The root cause of the conflict has never been determined or agreed upon, although it is believed that a mixture of religious and ethnic differences, shifting economic position, political struggles and a general downturn in the financial fortune of the region following the Asian financial crisis contributed to the fighting. Overall instability and political struggles in Indonesia have certainly also played their part in preventing a quick resolution to the conflict. In addition, outside influences in the form of militias and support of religious and independence struggles have contributed to prolonging the tension and the fighting.

-

In Far Eastern Indonesia there is a distinct ethnic difference with the indigenous populations being Melanesian compared with the Malay groups which are dominant west of Wallace’s Line. In West Papua there has been a separatist movement (the OPM) ever since the former Dutch colony became part of Indonesia in 1963. This was quite weak through much of the 1980s and early 1990s but there has since been an upsurge of opposition to Indonesian sovereignty (Murphy 1999; Dolven 2000). There has been violence directed at inmigrants from other parts of Indonesia (Far Eastern Economic Review, 12 October 2000, 14) and reported displacement of local populations by military activity.

-

Ethnic and sectarian violence has occurred also in Central Sulawesi. The United Nations (2002, 33) explained this as follows:

… a consequence of communal violence between Christians and Muslims. However, this is only part of the explanation. Tensions between different ethnic groups involving the local or indigenous population and migrants from other parts of Sulawesi or other islands in Indonesia, turf wars between criminal gangs, as well as political rivalries involving different parties, and longstanding historic animosity between coastal traders and upland farmers constitute the major causes of the conflict. Central Sulawesi is a “complex emergency”, causes and complicated by civil strife. The violence has led to rising tensions between Christians and Muslims, irrespective of the original trigger.

It is common in the media for these conflicts to be attributed to differences between ethnic groups in Indonesia but their causes are much more complex and especially to perceptions of differences in access to resources. These inequalities often result in tensions between ethnic and religious groups which usually have an element of newcomers versus longer established residents in them. The ‘newcomers’ in many cases are not first generation inmigrants but are descendants of earlier generations of inmigrants who are of a different ethnicity and/or religion of the local population. Accordingly, an interesting dimension of the forced movements associated with conflict is that in many cases they represent a reversal of earlier flows, although many of those involved may never have lived in their area of origin and may not retain linkages with family in that area.

The most discussed group among the ‘newcomers’ who have been made IDPs are former transmigrants from Java and their descendants that have been forced to leave and enter local refugee camps or return to the area that they or their ancestors had left several decades ago. The government transmigration program which aimed at resettling farm population from Java-Bali in less crowded outer island areas relocated up to ten million people in more than a century of operation (Tirtosudarmo 2001). The distribution of transmigrant settlers in the Outer Islands is shown in Fig. 13.13 but it is apparent that there is by no means a correlation between location of transmigrants and of the outbreak of conflict inducing forced outmigration. Indeed, the largest concentration of transmigrants located in Southern and Central Sumatra have been free of such conflict.

Destination of transmigrants, 1968–2000 (Source: Hugo 2002, 315)

The areas where transmigrants have come into conflict with local populations have been in West and Central Kalimantan, Central Sulawesi and West Papua. These are areas where a predominantly Muslim transmigrant population from Java has come into contact with a local Christian or animist local population. However, in all cases it is far too simplistic to portray the conflict as a Muslim-Christian confrontation. There have been elements of the newcomers being seen as intruders and given privileges denied longstanding residents, coastal dwellers versus inlanders, ethnolinguistic differences mixed with long simmering local resentments released with the national political transformations and the activities of criminal groups. The transmigrant:local clashes have perhaps been greatest in Kalimantan where the predominantly Madurese newcomers have been settling in West and Central Kalimantan, both under the auspices of the transmigration program and spontaneously, for a century.

While the Java-Outer Island movements associated with transmigration have dominated discussions of settlement in the Outer Islands, in fact there has been another diaspora which has been of greater scale in the eastern part of Indonesia. This has involved the so-called BBM representing the Bugis, Butonese, Makassarese – the three main ethnic groups originating in Southern Sulawesi. This group has a long history of seafaring and movement (Naim 1979), and for several centuries they have migrated westward to Eastern Kalimantan and Eastern Sumatra (Lineton 1975). In the post-Independence period, however, the bulk of the outflow from Southern Sulawesi has been toward the east. Figure 13.14 shows that these predominantly Muslim migrants have settled in areas dominated by Christian local populations in Maluku, East Nusatenggara, West Papua and, formerly, in East Timor. The movements have not only involved settlement but also long term circular migration. Hence like many of the transmigration flows it involved the insertion of a Muslim population into a Christian local community. However, the resentments which have grown among the BBM and local populations in some parts of Eastern Indonesia are not just religion based. Unlike the transmigrants, the BBM have not engaged in agriculture in their Eastern Indonesia destinations but have been involved in fishing, trading and small scale business, especially the latter. Their domination of local economies, shopkeeping, trading etc. has created some resentment among the longstanding populations (e.g. see Adicondro 1986).

BBM (Bugis-Butonese-Makassarese) migrations from South Sulawesi (Source: Hugo 2002, 317)

Hence while the conflicts are often depicted as an example of the effects of clashes between Islam and Christianity or Malay and Melanesian, this is greatly oversimplifying a complex situation.

Conclusion

As an independent nation, Indonesia has confronted and continues to face many challenges. It is one of the world’s most diverse nations not only in terms of ethnicity but geographically, culturally and economically. Ethnicity will remain an important dimension and is an important element in understanding differences in demographic behaviour. However, too often the complexity of the role of ethnicity and its linkages with economic and social processes are ignored or understated. The inherent difficulties in measuring ethnicity in a population census are exacerbated in Indonesia by political sensitivity, intermarriage and extensive mobility beyond the heartland of different ethnic groups. However, the inclusion of an ethnicity question in the censuses of 2000 and 2010 reflects an increasing maturity in Indonesia about its multicultural population. Although there has been considerable dispersal of different ethnic groups, there remains concentrations of particular groups in particular areas. Several of the smaller groups are concentrated in more peripheral parts of the archipelago and there are perceptions of neglect from the centre – Jakarta and Inner Indonesia, Java, Bali. It is easy for such resentments to gain an ethnic dimension. Accordingly, ethnic issues and sensitivities remain strong in Indonesia. However, the founders of the Indonesian state were emphatic in their insistence of equality between sukubangsa in the newly independent nation. There remains a relationship between ethnicity and political behaviour in Indonesia (Suryadinanta et al. 2003, 179) but it is not the only factor involved.

Indonesia is potentially entering a new era of increasing economic prosperity which could see it move from being the 16th largest economy in the world to the 7th by 2030 (Oberman et al. 2012, 1). Whether or not this is achieved will rely heavily on the maintenance of the political stability which has characterised it over the last decade. Ethnicity is one of the elements in the mix of potential threats to harmony. Maintenance of the vision of Indonesia’s founders to maintain ‘Unity in Diversity’ must be an important imperative of contemporary political leadership.

Notes

- 1.

Indonesian Population Census data used here is obtained from the Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics, website – http://www.bps.go.id/eng/

- 2.

Data on ethnic Chinese were only reported in 11 out of Indonesia’s 30 provinces where they are most strongly represented.

References

Adicondro, G. J. (1986). Datang Dengan Kapal, Tidur Di Pasar, Buang Air Di Kali, Pulang Naik Pesawat [Arrive by boat, sleep in the market, urinate in the river, return home in an aeroplane]. Jayapura: Yayasan Pengembangan Masyarakat Desa Irian Jaya.

Bruner, E. M. (1972). Batak ethnic associations in three Indonesian cities. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 28(3), 207–229.

Bruner, E. M. (1974). The expression of ethnicity in Indonesia. In A. Cohen (Ed.), Urban ethnicity. London: Tavistock.

Castles, L. (1967). The ethnic profile of Djakarta. Indonesia, 3, 153–204.

Coppel, C. A. (1980). China and the ethnic Chinese. In J. J. Fox, R. Garnaut, P. McCawley, & J. A. C. Mackie (Eds.), Indonesia: Australian perspectives. Canberra: Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University.

Dhume, S. (2001, April 26). Islam’s holy warriors. Far Eastern Economic Review, pp. 54–57.

Dolven, B. (2000, November 18). A rising drumbeat. Far Eastern Economic Review, pp. 72–75.

Fox, J. J. (1977). Harvest of the palm: Ecological change in eastern Indonesia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Geertz, C. (1963). Agricultural involution: The processes of ecological change in Indonesia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Goantiang, T. (1965). Growth of cities in Indonesia 1930–1961. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 56, 103–108.

Harvey, B. (1974). Tradition, Islam and Rebellion: South Sulawesi 1950–1965. PhD thesis, Cornell University, University Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

Hugo, G. J. (1975). Population mobility in West Java, Indonesia. PhD thesis, Department of Demography, Australian National University, Canberra.

Hugo, G. J. (1981). Road transport, population mobility and development in Indonesia. In G. W. Jones & H. V. Richter (Eds.), Population mobility and development: Southeast Asia and the pacific (Development Studies Centre Monograph No. 27, pp. 355–386). Canberra: Australian National University.

Hugo, G. J. (1987). Forgotten refugees: Postwar forced migration within Southeast Asian countries. In J. R. Rogge (Ed.), Refugees: A third world dilemma (pp. 282–298). Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield.

Hugo, G. J. (1999). Coping with the crisis through population movement. In International Labour Organisation (Ed.), Indonesia: Strategies for employment-led recovery and reconstruction (pp. 329–364). Jakarta: ILO.

Hugo, G. J. (2002). Pengungsi – Indonesia’s internally displaced persons. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 11(3), 297–331.

Hugo, G. J. (2012). Changing patterns of population mobility in Southeast Asia. In L. Williams & P. Guest (Eds.), Southeast Asia demography (pp. 121–164). New York: Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University.

Hugo, G. J., Hull, T. H., Hull, V. J., & Jones, G. W. (1987). The demographic dimension in Indonesian development. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Jones, G. W. (2004). Urbanization trends in Asia: The conceptual and definitional challenges. In A. Champion & G. Hugo (Eds.), New forms of urbanization. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Kraak, J. H. (1957). The repatriation of Netherlands citizens and Ambonese soldiers from Indonesia. Integration, 4(4), 348–355.

Lineton, J. A. (1975). Pasompe Ugi: Bugis migrants and wanderers. Archipel, 10, 173–204.

McBeth, J., & Djalal, D. (1999, March 25). Tragic island. Far Eastern Economic Review, pp. 28–30.

McNicoll, G. (1968). Internal migration in Indonesia: Descriptive notes. Indonesia, 5, 29–92.

Murad, A. (1980). Merantau: Outmigration in a matrilineal society of West Sumatra (Indonesian Population Monograph Series No. 3). Canberra: Department of Demography, Australian National University.

Murphy, D. (1999, April 29). The next headache. Far Eastern Economic Review, pp. 20-21.

Naim, M. (1973). Merantau, Minangkabau Voluntary Migration. PhD dissertation, University of Singapore, Singapore.

Naim, M. (1979). Merantau: Pola Migrasi Suku Minangkabau. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press.

Oberman, R., Dobbs, R., Budiman, A., Thompson, F., & Rossé, M. (2012). The archipelago economy: Unleashing Indonesia’s potential. Washington, D.C.: McKinsey Global Institute, McKinsey and Company.

Rambe, A. (1977). Urbanisasi Orang Alabio Di Banjarmasin [Urbanization of People from Alabio in Banjarmasin]. Banjarmasin: Faculty of Economics, Lambung Mankurat University.

Roosman, R. S. (1980). Irian Jaya refugees: The problem of shared responsibility. Indonesian Quarterly, 8(2), 83–89.

Siegel, J. T. (1969). The rope of god. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Statistics Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik – BPS) and Macro International. (2008). Indonesia demographic and health survey 2007. Calverton: BPS and Macro International.

Suryadinanta, L., Arifin, E. N., & Ananta, A. (2003). Indonesia’s population: Ethnicity and religion in a changing political landscape. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Suryadinata, L., Arifin, E. N., & Ananta, A. (2004). Indonesian electoral behaviour: A statistical perspective. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Tirtosudarmo, R. (2001). Demography and security: Transmigration policy in Indonesia. In M. Weiner & S. Russell (Eds.), Demography and national security (pp. 199–227). New York: Berghahn Books.

United Nations. (2002). Consolidated inter-agency appeal 2002 for internally displaced persons in Indonesia. New York/Geneva: United Nations.

Volkstelling (Population Census). (1933–1936). Definitieve Uitkomsten Van de Volkstelling 1930 (8 volumes). Batavia: Department van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel.

Ward, M. W., & Ward, R. G. (1974). An economic survey of West Kalimantan. Bulletin of Indonesia Economic Studies, X(3), 26–53.

Williams, L., & Guest, M. P. (2012). Demographic change in Southeast Asia: Recent histories and future directions. New York: Cornell University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hugo, G. (2015). Demography of Race and Ethnicity in Indonesia. In: Sáenz, R., Embrick, D., Rodríguez, N. (eds) The International Handbook of the Demography of Race and Ethnicity. International Handbooks of Population, vol 4. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8891-8_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8891-8_13

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-90-481-8890-1

Online ISBN: 978-90-481-8891-8

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)