Abstract

This chapter consists of two broader parts. The first discusses the macro-level demographic processes affecting the Hungarian community of Romania over the past century, including assimilation, ethnic differences in fertility and mortality, respectively, migratory processes, arguing that the negative trends in these domains are a consequence of the power asymmetries inherent in the nation-state. The second part starts from the assumption that censuses are inevitably political tools in the battle over the legitimate representation of social realities and provides an analysis of the processes of ethnic classification employed at the censuses, also discussing two important situations where census identification and everyday ethnic categorization do not necessarily fit, namely the case of Hungarian-speaking Roma and Csángós (Catholics of Hungarian origin) in the Moldova region of Romania.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

This chapter is an introduction to the last section of the book, which deals with societal and demographic macro-processes. The first broad part of the chapter (consisting of five subsections) provides an outline of the major demographic processes affecting Transylvanian Hungarians. This part relies mainly on census data and tries to synthesize some of the major conclusions of the ethno-demographic research focusing on Transylvanian Hungarians carried out in the last one and half decades. First, I discuss changes to the ethnic landscape in Transylvania, particularly the demographic evolution of the Hungarian community. As we will see, the number of Transylvanian Hungarians dropped significantly during the last 35 years. The next three subsections discuss factors contributing to this population decline: natural growth, migratory flows, and assimilatory processes. The fifth subsection of this part deals with the significant regional differences in the dynamics of the demographic and ethno-cultural reproduction of the Hungarian community.

While the first broad part of the chapter is mainly a positivist quantitative analysis of demographic processes, the second part undertakes a constructivist perspective and discusses the techniques of ethnic classification on different levels. First, I discuss census classification. I rely on Wimmer (2013) and on Rallu et al. (2006) and argue that a shift from a Herderian discursive order toward an integrationist one has occurred following the collapse of state socialism, altering/questioning the existing “regime of counting”. However, this shift was gradual and inconclusive. Consequently, both official and everyday ethnic classification remained attached to the Herderian paradigm, treating ethnic categories as bounded groups with mutually exclusive membership. Following these more general considerations, I discuss two groups connected to the Hungarian population in Romania, Hungarian-speaking Roma and the Csángós (Catholics of Hungarian origin) in Moldova. I will argue that in their case, standard census techniques of measuring ethno-national identity are highly problematic.

1 Demographic Processes. An Outline

1.1 The Dynamics of the Hungarian Population According to Census Data: 1910–2011

Censuses constitute the most important data sources concerning the changes in the ethnic structure of the territory under investigation. The last census carried out by the Hungarian Central Statistical Office was in 1910; thus, the results of this census can be compared to later Romanian census data (Table 1).Footnote 1

Census data show significant changes in the territory’s ethnic structure. The proportion of the titular category has increased sharply under Romanian sovereignty. According to the last Hungarian census in 1910, Romanians comprised 54% of the population. By 2011, they constituted almost 75%. The number and proportion of Germans fell drastically during the same period: While in 1910 they made up 10% of the total population, in 2011 their proportion barely reached 0.5%. The number and proportion of Hungarians also decreased, albeit less dramatically. In 2011, about 1.2 million persons declared themselves as Hungarian, representing 19% of the total population of Transylvania.Footnote 2 The number and proportion of Roma have been rising continuously since 1966. In 1966, less than 50,000 people identified themselves as such, while in 2011, their number exceeded 270,000.

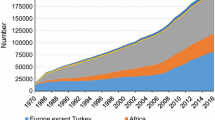

Based on demographic investigations, it is also possible to present the changes of the annual number of the Hungarian population for the 1964–2017 period (Fig. 1).Footnote 3

One can observe that (in the context of the repressive population politics of the Ceaușescu regime Footnote 4) the number of Hungarians increased until 1982, when according to our estimates, their number reached 1.732 million. A slow decrease already began during the mid-late 1980s, while following the regime change a more drastic drop in the number of Hungarians occurred. According to the 2011 census, there were 1.227 million Hungarians in Romania, meaning a 28% decrease compared to the early 1980s. This drastic demographic decline was caused by several factors, namely mass emigration, negative natural growth, and to a lesser degree, the assimilation process toward the majority.

1.2 The Natural Growth of the Transylvanian Hungarian Population

The natural growth of the Hungarian population is relatively well documented. The annual number of live-births can be estimated based on the age structure of the Hungarian ethnics, and additionally, the National Institute of Statistics registers the “nationality”Footnote 5 of the newborns and the deceased. According to the demographic calculations, the crude birth and death rates of the Hungarian population differ significantly from the national average, in spite of the fact that today there is no significant difference in the fertility (TFR) and mortality (life expectancy at birth) rates between the Hungarians and the national majority (Gyurgyík and Kiss 2010, pp. 70–87).

In Romania as a whole, natural growth was positive until 1992, and as a consequence, the country’s population also grew up to this year. Regarding Transylvanian Hungarians, the annual number of deaths surpassed the number of births for the first time in 1983. Between 1983 and 1989, there was practically zero natural growth rate, which meant that in the context of the intensifying out-migration of Hungarians, the population numbers were already declining. Following 1989, births numbers dropped,Footnote 6 while the number of deaths increased, bringing about a drastic negative natural growth rate and an annual population loss of 6–8 per thousand caused only by this factor (Fig. 2).

During the 1980s, the total fertility rate (TFR) of Hungarian women was below the national average. However, following the regime change, the differences compared to the national average diminished. Hungarians’ life expectancy at birth was also quite similar to that of the majority. In sum, one should emphasize that following the regime change, the negative natural growth of the Hungarian population was more drastic compared to Romania as a whole; however, this was not caused by lower fertility rates or lower life expectancy at birth, but by a less favorable age structure and an earlier process of aging caused primarily by previous migratory flows (Table 2).

1.3 Migratory Processes

Following World War II, Romania became a sending country without any significant influx of immigrants. According to the 2011 census results, the foreign-born population was below 150,000; the most numerous group within this population consisted of persons born in the Republic of Moldova, though their number did not exceed 37,000. The majority of those born abroad were the children of Romanian returnees.

On the contrary, emigration was quite significant even during state socialism. The number of emigrants officially registered between 1948 and 1989 exceeded 783,578 (Muntele 2003, p. 36). The real number of those leaving the country was certainly significantly higher than this figure.Footnote 7 One could highlight that the real goal of the former regime’s migration policy was not to keep out-migration at a minimum, but to select who should be allowed to leave (Horváth and Kiss 2015, pp. 108–110). The bulk of emigrants of this period belonged to various minorities: Jews (Bines 1998; Ioanid 2005), Germans (Fassmann and Münz 1994; Münz and Ohliger 2001), and Hungarians (Horváth 2005). In the case of the Jewish and German communities, a mass exodus took place in the context of the ethnically selective emigration policy of Romania and the ethnically selective immigration policies of Western Germany and Israel.Footnote 8 According to official statistics, Hungarians were not overrepresented among emigrants until the mid-1980s. Nevertheless, the number of irregular migrants began to rise sharply starting in 1986. Initially, Hungary was mostly a transit country for refugees who tried to reach Western European destinations. However, many refugees came to a halt in Hungary. Following 1987, it had become a common practice for Hungarian authorities not to return refugees to Romania, even if the legal codification of the question did not occur until 1989 (see Regényi and Törzsök 1988 for details). Hungarian authorities registered 47,771 immigrants from Romania between 1986 and 1989. The outflows did not stop after the collapse of Romania’s Communist regime and the proportion of ethnic Hungarians among irregular migrants reached 97% in March 1990, following the violent interethnic clashes in Târgu Mureș/Marosvásárhely Footnote 9 (Szoke 1992, p. 312). Meanwhile, the number of regular migrants also increased. As a consequence, the number of former Romanian citizens naturalized in Hungary grew from 866 in 1980 to 6499 in 1987 (Szoke 1992, p. 308). The increasing proportion of Hungarian ethnics among the total number of emigrants could be seen in the official Romanian statistics too, and if both irregular and regular forms of migration were taken into account, a huge wave of emigrants and refugees was observable. According to the estimates, the negative net migration of the Hungarian population in Transylvania was of 132,000 in the period between 1964 and 1992, while between 1987 and 1992 approximately 85,000 Hungarian ethnics left Romania (Table 3).

The collapse of the Communist regime profoundly altered the position of Romania in the European migratory system. As a consequence, the outflows have grown considerably and new forms of migration—e.g., temporary (Sandu 2006), circular (Sandu 2005), and educational migration (Brǎdǎţan and Kulcsár 2014)—have become widespread. However, Hungarians—due to their intensive out-migration toward HungaryFootnote 10—have remained clearly overrepresented among those leaving the country. According to demographic estimates, the negative net migration for Romania as a whole was 825,000 between 1992 and 2002, meaning an annual migratory loss of 3.6 per thousand. In the case of the Hungarian population, the population loss caused by migratory flows can be estimated to have been 106,000, meaning an annual net migration rate of −6.6 per thousand. In other words, 13% of the migratory loss of Romania was “suffered” by the Hungarian community, comprising 7.2% of the country’s population.

Following the turn of the millennium (in the pre-accession period and after the country’s EU accession), the migratory regimeFootnote 11 in Romania changed again drastically. While during the 1990s the Western European states had tried to limit the number of Eastern Europeans entering their labor market, the restrictions were gradually lifted before and after EU accession. Next to Poland, Romania became the major sending country of Eastern European emigrants. According the World Bank’s bilateral migration matrix, more than 3.4 million Romanian citizens lived abroad in 2013. According to (preliminaryFootnote 12) census results, the migratory loss of Romania was 2.4 million between 2002 and 2011, meaning an annual net migration rate of −11.4 per thousand. In the case of the Hungarian population, the migratory loss can be estimated to be 110,000, meaning an annual net migration rate of −8.3 per thousand. In other words, in the context of the country’s massive depopulation, Hungarians are no longer overrepresented.

1.4 Assimilation: Operative Definition and Processes

The notion of assimilation is a much debated issue in the literature of ethnic relations. The problem that demographers face is that in order to be able to analyze its demographic dynamics, they need a Hungarian “population” defined as a bounded entity. Further, they also need to define input and output values, which in case of a spatially defined population are the numbers of births, immigrants, deaths, and emigrants.Footnote 13 However, the Hungarian population of Transylvania is not territorially defined, but ethno-nationally or ethno-linguistically. As a consequence, demographers also have to take into account linguistic or identity shifts as input/output variables. The majority of demographic investigations used ethno-national self-identification as the criteria for delimiting the Hungarian population. As a consequence, assimilation was treated as a shift in self-identification from the minority category toward the majority.

In the following section, I discuss to what extent the shift in self-identification affected the dynamics of the Hungarian population. I also introduce the concept of assimilation as it was used in ethno-demographic research focusing on Transylvanian Hungarians. In a later part of this chapter, I will compare the techniques of classification used in censuses and in everyday practices, while in the next chapter (dealing with assimilation and boundary reinforcement) I will present a more theoretically informed and detailed analysis of ethnic boundary making and boundary crossing in Transylvania.

One should emphasize at the very beginning that compared to negative natural growth and massive emigration, assimilation has been a factor of secondary importance in what concerns the decrease in the Hungarian population. The demographic literature focusing on Transylvanian Hungarians distinguished three forms of assimilation when analyzing census data (Szilágyi 2002, 2004):

-

1.

The change of one’s (census) self-identification, or the case in which someone who was registered as Hungarian in the previous census identifies as Romanian in the next census.

-

2.

Difference between self-identification and pervious hetero-identification, or the case when a person becoming an adult identifies as Romanian despite being previously classified by her or his parents as Hungarian.Footnote 14

-

3.

The decrease in the capacity of intergenerational ethno-cultural reproduction, or the case in which Hungarian parents are unable to transmit their ethno-cultural traits (identification, language, etc.) to their children.

This typology was used as an operational definition of assimilation in investigations relying on census data. These investigations highlighted that the direction and the channels of the identity shift are relatively obvious. Changes in census self-identification are relatively rare,Footnote 15 while the decrease in capacity of intergenerational ethno-cultural reproduction is connected to ethnically mixed marriages.Footnote 16 While in the vast majority of ethnically homogenous families the identification (classification) of children is taken for granted, in ethnically mixed families parents have to choose between different alternatives of ethnic socialization. And if in a society the relation between ethnic categories is hierarchical, these choices will prioritize more prestigious categories over less prestigious ones (Laitin 1995; Finnäs and O’Leary 2003). While 12–13% of Transylvanian Hungarians were living in ethnically mixed marriages in 2011, less than one-third of the children of mixed ancestry were registered as Hungarian in censuses following the regime change. These imbalances of the models of ethnic socialization in mixed families affect primarily the reproductive capacities of dispersed Hungarian communities, where the proportion of mixed marriages is higher, while the probability of identity choices leading toward the minority category is lower.Footnote 17 Next to (ethnically mixed) families, another institutional channel of assimilation is Romanian-language education. In some areas (where the proportion of Hungarians is rather low), the majority of Hungarian children (even of those growing up in homogenous families) are educated in the majority language. Under these circumstances, the intergenerational ethno-cultural reproduction in ethnically homogenous families cannot be taken for granted either.

1.5 Regional Differences of Demographic Dynamics

One should emphasize that the demographic prospects of the Hungarian community are highly diverse. As a rule, the higher the proportion of Hungarians, the better the chance of demographic and ethno-cultural reproduction of the Hungarian community in the given region. In what follows, I will analyze the difference in the demographic dynamics of the four regions defined in the introductory chapter of the volume. These regions are the ethnic block area of Székely Land, Partium, an ethnically mixed region next to Hungarian border, Central Transylvania, comprising the major towns of Cluj/Kolozsvár and Târgu Mureș/Marosváráshely, and the rest of Transylvania, where dispersed Hungarian communities live among a large Romanian majority.

The regional differences of the demographic dynamics are synthesized in Table 4. It should be noted that in the Székely Land the population decline was slower compared to Romania as a whole, while the proportion of Hungarians in the region has not decreased at all. On the contrary, in 1992 almost 350,000 Hungarians had still lived in dispersed communities but their number has dropped to 200,000 by 2011.

2 Ethnic Categorization: Official and Everyday Practices

The study of demographic and societal macro-processes affecting Transylvanian Hungarians is impossible without analyzing census data. However, their use raises some severe methodological and epistemological problems. First, each census is per definition a political act (Kertzer and Arel 2002). The aim of the state administrations conducting censuses is not only to obtain information about social realities but also to form and change them (Scott 1998). As a consequence, censuses can be perceived as powerful tools of the classificatory struggles over the legitimate representation of social reality. Second, the census is the most widespread and common form of official categorization. However, official categories do not necessarily match the categories used in everyday settings. Consequently, censuses sometimes obscure rather than reveal complex social realities.

2.1 Changing Techniques of Official Classification

Census classification should be understood in its discursive and political context (Kertzer and Arel 2002). In this regard, changes to the political utilization of official categories and the broader discursive order shaping ethnic classification are of primal importance. In what follows, I will rely on two complementary conceptual frameworks. The first is that of Rallu et al. (2006) who outline a typology of the “regimes of counting”. The second was outlined by Wimmer (2013) and focuses on the shift between the Herderian and integrationist discursive orders concerning ethnic relations.

“Regimes of counting” refers to official classification not only at a technical/methodological level but also includes policies aimed at managing ethno-cultural differences that lie behind the different techniques of counting. The typology distinguishes between four regimes of counting: (1) counting to dominate; (2) not counting in the name of the republican idea of national unity and integration; (3) counting or not counting in the name of multiculturalism; and (4) counting to eliminate discrimination (Rallu et al. 2006, pp. 534–536). I will use only the first two, although I recognize that the other two might become of central importance in Romania too.Footnote 18

The first regime of counting, namely counting to dominate, is typical in colonial situations. Many authors have argued that colonial administrations classified people in distinct and well-distinguishable categories in order to administer them and to sustain the hierarchical order of ethnic or racial categories (Anderson 2006; Scott 1998). Importantly, Rallu et al. argue that Eastern European regimes of counting can also be classified as such (2006, pp. 534–535). Indeed, the very legitimacy of the state’s sovereignty over a territory is based on the fact that the titular group constitutes a statistical majority. This is why there is a necessity to (re)produce this majority through statistical means. Actually, ethnic demography has been central to debates over census classification in Eastern Europe throughout the last one and a half century.

The major aspects of Romanian census classification took shape in the interwar period, the 1930 census being a constitutive act in this respect. On the one hand, the emerging census classification was in line with the tendencies in other Eastern European states (Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and also the Soviet Union). On the other hand, the classification techniques of the 1930 Romanian census can be perceived as the antithesis of the previous techniques of classification employed by the statistical offices of the Hapsburg, Hohenzollern, and Romanov Empires.Footnote 19 In these empires, techniques of counting were quite similar to those used in the second half of the nineteenth century, ethnic classification based on mother tongue, or private language use being of central importance. Language was considered by German, Russian, Austrian, and Hungarian census takers as an “objective” indicator of a culturally defined nationality and, as such, was put in opposition with self-identification, characterized as too “subjective” to define one’s real belonging (Arel 2002). The Hungarian censuses carried out between 1880 and 1910 categorized the population according to mother tongue, defined as the language best spoken by the respondent at the moment of the census. This interpretation of the national belonging was inspired by the contemporary liberal concept of the Hungarian nation, which accepted persons of allogeneic origin as members of the national community if they had been able and willing to speak Hungarian. This technique (sharply criticized by the contemporary Romanian public opinion and statisticians) obviously reflected the effects of linguistic Magyarization too.

The successor states of the Hapsburg and Romanov empires altered the classification by mother tongue and put stronger emphasis on both ethnic origin (ancestry) and self-identification.Footnote 20 The main purpose was to diminish the proportion of formerly dominant groups. In Romania, the 1930 censusFootnote 21 introduced nationality (naționalitate) as a self-declared ethno-national belonging; however, according to the instructions for enumerators, nationality was also linked to ethnic origin (neam). Further, the definition of mother tongue (which was asked next to nationality) was altered, pushing classification again toward ancestral language: While in the Hungarian census “mother tongue” had been defined as the language best spoken, the 1930 Romanian definition referred to the language used in one’s family during early childhood. This change in counting methodology was of paramount importance regarding the categorization of Hungarian-speaking groups of allogeneic origin, most importantly that of Magyarized Jews and Swabians. The (mostly Hungarian-speaking) Jewish population of Transylvania numbered 170,000 when the 1930 census was taken.Footnote 22

The Romanian regime of ethnic classification can be characterized by a high level of inertia: The techniques of ethnic classification have changed little since the 1930 census. Nevertheless, one could witness a (potentially) radical but yet inconclusive change of the Romanian regime of counting in the last decade. Kukutai and Thompson (2015) argued that the politics of ethnic classification and counting are affected not only by national historical legacies but also by the international environment. In this respect, it is of central importance that Romania (among other Eastern European states) has joined the EU. As Simon (2012, 2017) argued, regimes of counting developed differently in the Western and Eastern part of Europe. On the one hand, counting by mother tongue and (culturally defined) ethno-nationality was widespread in Eastern Europe. On the other hand, Western European states (even if they practiced a detailed ethnic classification in their colonies) were reluctant to classify their metropolitan subjects by ethnicity mainly in the name of the national unity. Following World War II, ethnic classification was often associated with state-committed atrocities against minorities, especially those committed by the Nazi regime. Consequently, a regime of “not counting” in the name of integration has evolved and it is still dominant in Western Europe (even if it was questioned by those urging for counting ethnicity in order to combat discrimination).Footnote 23 The dominance of the integrationist framework and of the regime of “not counting” put pressureFootnote 24 on the “ethnicist” regimes of counting in Eastern Europe. This pressure (combined with the national legacies and the inertia of the statistical offices) has led to a yet inconclusive, but potentially radical, shift of the regime of counting.

In a broader sense, the Romanian regime of counting was deeply embedded in what was called by Wimmer the Herderian discursive order concerning ethnic relations (2013, pp. 16–44). According to Herder, the social world is composed of people (ethnic groups or nationalities) who are bounded groups sharing a specific cultural heritage embodied in their language, characterized by internal solidarity and a common sense of identity. This Herderian discursive order used to be in a hegemonic position until recently and had rarely been questioned by those using official statistics. It is important that Transylvanian Hungarian elites were (and are) also attached to the Herderian paradigm and used the same language of counting in their claims making. This is why they engaged in intensive identity campaigns during each census following the regime change but have not questioned the very logic and the political significance of counting (Varga 1998, pp. 220–240, for the 1992 census campaign; Brubaker et al. 2006, pp. 151–160, for the 2002 one). Nevertheless, the dominance of the Herderian paradigm has been eroded by the integrationist discourse that gained ground during the last one and a half decade.Footnote 25 According to this integrationist discursive order, the social world is no more made up by people, ethnic groups, or nationalities but is composed by an ethnically unmarked “social mainstream” on the one hand and by some ethnically marked and particular groups on the other hand. From this perspective, ethnicity is not an attribute that all people have, but it is a quality that characterizes people belonging to ethnically marked minority categories in particular situations.Footnote 26

One can argue that today in Eastern Europe the integrationist and the Herderian discursive orders overlap. This is sometimes conducive to chaotic and in-between techniques of counting. Eastern European states are no longer unequivocally determined to count their populations ethnically or to classify people in bounded and mutually exclusive categories. This hypothesis can be underpinned by the several arguments. (1) First, in some cases even not counting was considered. In Hungary, for instance, initially there was a decision of the government to omit questions concerning ethno-cultural traits in the 2011 census. This was supported by the majority of social scientists engaged in the research of ethnicity. The questions concerning (ethno-)nationality, mother tongue, and spoken languages were reintroduced following the electoral victory of right-wing parties in 2010. In other Eastern European countries, the option of not counting was not seriously considered. However, the communication campaigns of the censuses markedly facilitated non-response to questions concerning ethnicity by stressing that answering them (contrarily to other questions) was not obligatory. The proportion of non-responses was of 14.7% in Hungary, 9% in Bulgaria, 7.1% in Slovakia, and 2.1% in Serbia. In Romania, there was a unique situation. In 2011, a traditional paper-and-pencil-based census was carried out, which counted 19 million people and registered a less than 0.3% non-response rate to the question concerning ethnicity. However, eventually data about 1.2 million persons were added to the census database from the population register. As the population register does not contain data concerning ethnic identification, the ethnic background of these people (6.2% of the population) is “unknown”. (2) Second, the classification of people into mutually exclusive categories also came under attack. Hungary was the first state introducing the possibility of multiple census identifications both for “nationality” and for mother tongue (Kapitány 2013). In Romania, the option of multiple identifications was considered for the first time in 2011. However, initiatives toward this direction (proposed by the Romanian Institute for Research on National Minorities and by some Roma NGOs) were rejected by the Central Census Committee of the Romanian Government.

Before discussing the match between census classification and everyday ethnic categories, I would like to emphasize that from the perspective of minority groups, the shift toward an integrationist discursive order and a statistical regime of not counting is not an unequivocally positive development. First, politically active minorities usually advocate for the official recognition of ethnic diversity. Counting is a precondition of institutionalized power-sharing and autonomy. Authors inclined toward the integrationist perspective emphasize the dangers of empowering minority elites and delimiting the ethnic groups. They tend to discuss “official ethnicity” focusing on non-democratic regimes and on violent ethnic conflicts, with perhaps the Soviet Union (Hirsch 2004) and Rwanda (Uvin 2002; Longman 2001) being the most frequently discussed cases. Nevertheless, ethnic registers exist also in other cases where power-sharing and forms of autonomy led to peaceful ethnic coexistence under the conditions of democratic regimes, such as in Slovenia, Finland, post-Milošević Serbia, or South Tyrol. Second, the asymmetry between minority and majority categories could be even more accentuated in the integrationist discursive order and in the regimes of not counting. The “ethnicist” regimes of counting were aimed at underpinning the legitimacy of state sovereignty and to reproduce the dominance of the titular majority. However, from an epistemological point of view, the majority remained only one of the ethnic groups, even if the most numerous and dominant one. In the integrationist discursive order, the very epistemological status of the majority and minority becomes different, as “majority” is redefined as an ethnically unmarked “mainstream”. In this new logic of markedness,Footnote 27 the national majority loses its well-bounded contour and becomes hidden by the discursive order. However, this only means that belonging to the majority becomes even at the very conceptual level taken for granted (unmarked), while belonging to the minority becomes an unusual attachment to something defined as particular (the marked ethnicity). Third, it is also obvious that in Eastern Europe nationalizing states often use an ambivalent discourse alternating between an ethnically marked and an ethnically unmarked definition of the national majority. In previous chapters of this volume, we emphasized the duality of the Romanian minority policy regime. One may argue that the continuous back and forth between the integrationist perspective and ethnic democracy is an inherent characteristic of this regime.

2.2 Informal Classification and Identification in Everyday Settings

The next question is to what extent census classification (which remained actually connected to a Herderian definition of people) fits relevant identities and ethnic categories used in everyday settings. Generally speaking, ethnic classification happens in quite different contexts or settings. Jenkins places these contexts of classification on a continuum between formal and informal (2008, pp. 65–74). Official classification (the most obvious example being the census) takes place in the most formal setting. Informal everyday interactions are at the opposite end of the continuum and between these ends one can find more or less formal contexts, such as political representation (the question is whether ethnicity is politically salient), the labor market (where ethnic belonging may have severe consequences), or the marriage market. It is important to note that ethnic identification or categorization can be inconsistent among contexts and can change from one setting to another.

One can argue that in the case of Transylvanian Hungarians, census classification fits relatively well with the categories used in everyday settings and the identities of those in question. First, the two attributes used by Romanian censuses—namely self-identification with the Hungarian ethnic category and Hungarian as the mother tongue—are the major components defining membership in the Hungarian category in everyday interactions too. Furthermore, these elements, called the two major constitutive rules of identity by Abdelal et al. (2009), overlap in the case of Hungarians in the vast majority of times. According to the 2011 census results, the number of persons declaring Hungarian as their ethnicity or mother tongue was 1.24 million; 97.1% of them were classified as Hungarians in both dimensions. Second, in the majority of cases, Hungarian identification is relatively consistent across different contexts. This can be related to the psychological aspects of ethnic socialization. According to Fenton (2003, p. 88) and Jenkins (2008, p. 48), under certain social and institutional circumstances, especially when ethnic cleavages appear in well-defined forms in everyday life, people deeply internalize group membership and ethnic belonging during early childhood. In these cases, the internalization of ethnic belonging may go hand in hand with the internalization of its markers, such as language use. When this is the case, ethnicity is inscribed in the deepest layers of personal identity, like gender, for example. In such cases, ethnic identification is not independent from psychological, emotional, and cognitive constructs of personality, nor is it separate from notions of personal integrity, security, and safety. Under these circumstances, identities are less contextual and less fluid and the psychological price of leaving the group can be quite high.

Obviously, this is not to say that identification is not context dependent among Transylvanian Hungarians and that they would perceive each situation through ethnic lenses and act accordingly.Footnote 28 In a representative survey carried out in 2016, 1200 randomly selected self-identified Hungarians were asked whether there were situations in their lives in which they felt Romanian. Then, if the answer was affirmative, respondents were asked to describe the situation in an open-ended question. The first important result was that 17% responded affirmatively, while 83% declared that they never felt Romanian. The second important result refers to the contexts in which Hungarians reported having felt Romanians. People living in ethnically mixed families answered more frequently in the affirmative, showing that Hungarians consider this a setting where one can “become a Romanian”. Situations abroad were also frequently mentioned. These situations can be connected to official/passport identity or to a feeling of solidarity with their fellow citizens while abroad. Some mentioned that they felt Romanian when they succeeded to behave in a relaxed manner in informal settings among Romanians. Others mentioned that they have a kind of double identity and feel as though they belong to the country. Institutional settings, such as workplaces, the (Romanian-language) school, and the army, were also mentioned (Table 5).

In sum, in the case of an average Transylvanian Hungarian (if such a person would exist), census classification matches relatively well the categories used in everyday settings, as linguistic competences and subjective self-identification are the most important constitutive rules of Hungarian identity. Further, ethnic identity is relatively consistent across different settings. Nevertheless, there are some contexts in which identification with the national majority is more likely. These are first of all in ethnically mixed families, abroad, and in institutional settings external to the parallel Hungarian pillar.

3 Outlier Categories: Hungarian-Speaking Roma and Csángós in Moldova

It is also important that there are several well-distinguishable categories connected to Hungarians in Romania for which census classification is an inadequate tool of measuring identity. Historically, Hungarian-speaking Jews and other allogeneic groups could be considered as such. Today, the three most important categories for which census classifications are not adequate are ethnically mixed (Hungarian–Romanian) families, Hungarian-speaking Roma, and Csángós (Catholics of Hungarian origin) in Moldova. In what follows, I discuss the two latter categories, while ethnically mixed marriages will be discussed in a separate chapter.

3.1 Hungarian-Speaking Roma

The contested character of the Roma identity in Eastern Europe, as well as the intensive classificatory struggles to define the location and the consequences of ethnic boundaries between Roma and non-Roma, has been well explored in the literature (Emigh and Szelényi 2000; Ladányi and Szelényi 2006). The first important aspect emphasized by researchers is that in many cases external categorization as Roma does not always align with self-identification. This is why censuses and quantitative investigations have difficulties measuring and treating Roma identity as a clear-cut variable (Rughiniş, 2010, 2011). Previously, I argued that in the Transylvanian Hungarian case, attributes measured by censuses fit relatively well with the constitutive norms of Hungarian identity used in everyday settings. If someone speaks Hungarian fluently and declares himself or herself Hungarian, he or she is usually recognized as a category member. However, this is not the case for Hungarian-speaking Roma. Even if Hungarian is their sole spoken language and they declare themselves as Hungarians, Roma are barely recognized as members of the minority community. While in the maintenance of the Romanian–Hungarian boundary “groupness” and the institutions underpinning this groupness have a decisive role, for the boundaries between Roma and non-Roma social closure and exclusion are far more important. Ladányi and Szelényi (2006) argued along this line and highlighted that in the social construction of Roma ethnicity external classification is rather important. Moreover, this external classification is in many cases completely independent of linguistic skills and self-labeling. When external observers construct the category of Roma, the most important criteria are racial markers (skin color) and a way of life perceived as Roma. Ladányi and Szelényi carried out an interesting experiment (2006, p. 140). First, they asked field operators to classify the respondents of their survey as either Roma or non-Roma. Then, they asked the operators to fill in another questionnaire concerning the criteria used in the process of ethnic classification. 42% of the Romanian field operators reported that skin color was very important, while another 32% said that it was an important criterion when classifying the respondents. The (“Gypsy”) way of life was very important for 47% and important for further 33%. It should be mentioned that self-identification was less important than considering racial elements and way of life; 40% mentioned that it was very important, and another 14% said that it was important, while 46% of the operators reported that self-identification of the respondents was not important at all when classifying them as either Roma or non-Roma.

The Romanian Institute for Research on National Minorities carried out an exhaustive survey of Roma communities in Romania, contacting local administrations and asking them to estimate the number of Roma living on their territory. Data concerning segregated Roma neighborhoods within the given administrative unit were also requested. According to the survey, the estimated number of those classified as Roma in Romania was of 1,215,846,Footnote 29 with an estimated 724,844 living in compact Roma neighborhoods or the so-called colonies. In these “colonies”, Hungarian was one of the three most frequently used languages (alongside Romanian and Romani). Hungarian speakers are clearly overrepresented among Roma living in segregated neighborhoods: Almost 11% of them most frequently utilize Hungarian in their daily communication (Horváth and Kiss 2017). The estimated number of all Hungarian-speaking Roma (living in segregated neighborhoods or among non-Roma) is around 110,000. The vast majority of Roma in the Székely Land, Satu Mare/Szatmár county, and northern Bihor/Bihar are Hungarian speakers.

3.2 Csángós of Moldova

The Csángós of Moldova constitute a particular population connected to but also distinguishable from Hungarians in Romania. The notion of national minority may be misleading in their case. While there is a clear sense of ethno-cultural distinctiveness vis-á-vis the dominant group among them, in the historical process of their identity formation, no national movement played any significant role (or only the national movement of the dominant majority played such a role leading to pronounced assimilation). It is also important that this minority community lacks institutional channels of social mobility controlled by their own elites.Footnote 30 Consequently, social mobility and the exit from traditional rural communities also imply assimilation into the dominant group.

In the case of the Csángós of Moldova, the most important element of ethno-cultural distinctiveness is their Roman Catholic faith in a predominantly Romanian Orthodox environment. In some of their rural communities, this is completed by the use of an archaic Hungarian dialect (strongly influenced by the Romanian language). However, in the history of the Csángós, one cannot find the phases of Eastern European national awakening described by Hroch (1985). “Indigenous” (Csángó) intellectuals have never been, for instance, preoccupied in mapping and canonizing traditional Csángó folk culture in spite of the fact that Csángós have become a powerful symbol of the authentic Hungarian folk culture among Hungarian intellectuals beginning with the last decades of the nineteenth century. This discourse and the intensive research carried out by Hungarian ethnographers were less relevant for the Csángó community and had little impact on their identity formation. Nevertheless, their sense of belonging was powerfully shaped by the emerging institutional infrastructure of the Romanian state. It is important to note that the “indigenous” Csángó intelligentsia, most importantly the Roman Catholic clergy of Csángó origin, successfully propagated a sense of Romanian national belonging and origin.Footnote 31

In Moldova, there was no institutional background for a Hungarian (or at least non-Romanian) identity project. In a historical perspective, two relatively short periods can be perceived as an exception. First, following World War II, the Hungarian Popular Alliance (Magyar Népi Szövetség), a mass organization dominated by Communists, established Hungarian-language schools in almost one hundred Csángó villages. However, this experiment was neither long lasting nor particularly successful.Footnote 32 The second institutional experiment took place after the collapse of communism, when the Csángó Educational Program was launched. In the 2011/2012 educational year, there was facultative Hungarian-language education in 39 Csángó villages with more than 2500 children enrolled. In 21 villages, the program was part of the official educational curriculum, while in 17 locations it was organized outside of schools. According to Papp and Márton (2014), the results of the program were quite modest in terms of both increasing the Hungarian-language proficiency of children and establishing channels of educational mobility toward the Hungarian-language schools.

As for the number of Csángós, census data are of limited use. According to 2011 census results, slightly more than 181,000 Roman Catholics lived in Bacău, Iași, Neamț, and Vrancea counties. This could be considered the maximum possible number of Roman Catholics of partial Hungarian origin. However, only a minority of this group speaks the Csángó-Hungarian dialect and their vast majority can be characterized through a Romanian national identity. Vilmos Tánczos, a Transylvanian Hungarian ethnographer (employed as a census enumerator in one of the Csángó villages in 2011), argued that census classification was not a proper tool to reveal the distinctiveness of the Csángós vis-á-vis the Romanian majority (Tánczos 2012). In the official context of census classification, the majority of Csángós declare Romanian as their ethnicity and mother tongue. Nevertheless (ethnic or quasi-ethnic), distinctions in everyday life between Orthodox Romanians and Catholic Csángós exist. According to a study carried out between 1994 and 1996, approximately 62,000 persons spoke the Csángó-Hungarian dialect. One and a half decades later (between 2008 and 2009), this number was estimated to slightly more than 48,000, which is indicative of a rapid linguistic shift being underway (Tánczos 2010).

Notes

- 1.

The methodological problems of such a comparison are multiple. In a later subsection of this chapter, I will discuss the changes of the techniques of census ethnic classification. Next to this problem, the results of both the Hungarian and Romanian censuses were contested. As for an analysis of the (defensive) reactions of the Romanian public opinion to Hungarian censuses between 1880 and 1910, see Botoş et al. (2016). Blomqvist discussed in detail the role of censuses in the nationalizing policies of Hungary and Romania between 1880 and 1941 (2014, pp. 75–85; 222–224; 278–280; 333–334). Brubaker et al. highlighted that struggles over census results were an immanent part of ethnic politics after the collapse of communism too (2006, pp. 151–160). Our starting point is that censuses are not simple bureaucratic exercises but are part of the political struggle over the legitimate representation of social reality (Kertzer and Arel 2002). As a consequence, one cannot omit census data but should be careful when using it in the analysis of ethno-demographic processes.

- 2.

From an administrative point of view, the 2011 census was quite chaotic. It was designed as a traditional census with enumerators and face-to-face interviews with paper-based questionnaires. Slightly more than 19 million persons were registered with this methodology on the entire territory of Romania. However, following the census, the government decided to supplement the census database using the population register. Due to this exercise, the population of Romania rose above 20 million, which is obviously an overestimation of the country’s resident population. As the population register does not contain information about ethnic belonging, we lack this information for 1.2 million people. Similarly to the method of the National Institute of Statistics, we calculated the proportion of ethnic categories from the number of people whose ethnic identification was known. On the methodological problems of the 2011 census, see Ghețău (2013).

- 3.

These estimations were based on retrospective inverse projections. This method is used in historical demographic research (Lee 2004) to estimate missing data on vital statistics, and it is an inverse of demographic projections using the cohort-component method. See the detailed analysis and the methodology in Gyurgyík and Kiss (2010, pp. 66–70).

- 4.

In 1966, a drastic ban on abortion came into force. While in other Eastern Bloc countries positive incentives were the main tools of population policy, in Romania the emphasis was on punitive measures. On this, see Kligman (1998).

- 5.

The parents are asked to classify their newborn by nationality (naționalitate), meaning in this case ethno-national background. As mentioned already, a similar terminology was used in censuses until 2002, when it was replaced by ethnicity (etnie). In the vital statistics, the terminology has not been changed, leading to more and more confusion, as naționalitate today can be interpreted as both ethno-national belonging and citizenship. I will discuss these aspects later.

- 6.

There were 22,000 Hungarian births in 1989 and only 14,000 in 1992.

- 7.

- 8.

Brubaker (1998) called this process migration of ethnic unmixing.

- 9.

- 10.

The migration of Hungarians also took various forms. Many Transylvanian Hungarians found employment in the secondary labor market of Hungary (Bodó and Bartha 1996). However, the emigration of highly skilled segments (Gödri and Tóth 2005) and the educational migration (Szentannai 2001; Horváth 2004) of the Hungarian youth has also been significant.

- 11.

The migratory regime is the totality of legal norms and institutions regulating the possibility of exit (in the sending country) and of the entrance and integration (in the receiving country).

- 12.

As mentioned already, the enumerators had registered slightly more than 19 million persons and this number was completed eventually from the population register. The migratory loss calculated based on preliminary figures is more or less in line with the mirror statistics of major receiving countries concerning immigrants from Romania.

- 13.

Now, we omit the problem that the spatially bounded character of populations (societies) cannot be anymore taken for granted. In an era of transnational migration, people can be part simultaneously of more than one society. In other words, the demographic model taking migration as an output and input variable is an oversimplification. See Faist (2010).

- 14.

- 15.

Of course, identification with ethnic categories in everyday settings is highly contextual in Transylvania too. See Brubaker et al. (2006, pp. 207–239). However, probably due to identity campaigns and ethno-political struggles, census identification is relatively rigid and reflected.

- 16.

One should emphasize that ethno-cultural reproduction and assimilation in this framework are macro-level phenomena characterizing a population and not individual biographies. See also Brubaker (2001).

- 17.

In Timiș/Temes, Hunediara/Hunyad, Sibiu/Szeben, and Caraș Severin/Krassó-Szörény counties, the majority of younger generation Hungarians engage in ethnically mixed marriages. In the Hungarian-majority region of Székely Land, the proportion of mixed marriages is below 5%, while the majority of children growing up in mixed marriages will have Hungarian as their first language.

- 18.

The outlines of a regime of counting to avoid discrimination can be observed in connection with the issue of Roma integration. For instance, applicants for (nationally administered) EU funds for combating poverty and marginality are explicitly asked to annex detailed descriptions of Roma communities they would like to deal with. Local authorities can also apply for (substantial) funds following a careful mapping of Roma communities of their administrative units. See http://www.fonduri-structurale.ro/stiri/16699/pocu-ghidul-solicitantului-pentru-implementarea-strategiilor-de-dezvoltare-locala-in-comunitatile-marginalizate-publicat-spre-consultare.

- 19.

There was a discontinuity compared to the censuses of the pre-World War I period in the Old Romanian Kingdom, which did not gather information about cultural belonging but asked only about the citizenship of the residents.

- 20.

This has happened both in the successor states of the Hapsburg monarchy (among them in Romania) and in the Soviet Union. As for the Soviet “regime of counting”, see Hirsch (2004).

- 21.

Several authors emphasize the “objectivity” of the 1930 census, highlighting that it met international standards of the era (Varga 1999; Blomqvist 2014, p. 278). The latter may be true; however, meeting international standards does not mean that the 1930 census was independent of political considerations or that it can be interpreted without taking into account classificatory struggles.

- 22.

On the Hungarian reception of the 1930 Romanian census, see Seres and Egry (2011). It was frequently mentioned by Hungarian commentators that in many cases census enumerators in fact hetero-identified Hungarian-speaking Jews, Swabians, Armenians, or Hungarian Greek Catholics of allegedly Ruthenian or Romanian origin.

- 23.

See on this topic Simon (2008), who analyzes the struggles over official ethnic classification in France, which is most strongly attached among the European states to the republican idea of national unity and ethnic blindness.

- 24.

It is better to conceptualize this pressure as indirect, as Eurostat or other EU-level institutions do not formulate direct requests to Eastern European national statistical offices to alter their techniques of ethnic counting. However, many Eastern European social scientists and statisticians have become fascinated by the integrationist ideal of not counting and many find the actual regimes of counting in Eastern Europe inadequate or immoral. They might push toward an integrationist regime of not counting, as it happened in Hungary before the 2011 census, when the Census Committee of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences formulated such a recommendation (which was ultimately rejected by the newly elected right-wing government in 2011).

- 25.

- 26.

- 27.

The notion of markedness denotes the asymmetries exiting in linguistic and cognitive structures. Most importantly, it emphasizes that the relation between categories is not symmetrical, a dominant, and a subordinated category exists. Initially, this terminology had been used in structuralist linguistics but ultimately it was borrowed by social scientists to describe the cognitive mechanisms beyond social categorization. Waugh (1982) used it to describe the relation between categories of man and woman, white and black, sighted and blind, heterosexual and homosexual, fertility and barrenness. It is also important that the relation between categories is context dependent. A category that is marked in one social context could be the unmarked one in another context. Brubaker et al. (2006) gave us examples of everyday contexts where the usually marked category of Hungarian becomes unmarked, while the usually unmarked Romanian becomes marked.

- 28.

- 29.

The response rate was 98.1% for the total number of 3284 municipalities of Romania.

- 30.

This is one of the characteristics of ranked systems of groups described by Horowitz (1985).

- 31.

On the problems of being simultaneously Roman Catholic and Romanian, see Diaconescu (2008).

- 32.

Communists tried to use the Hungarian identity project to reduce the influence of the Roman Catholic clergy. The Hungarian schools functioned between 1950 and 1955 (Nagy 2011, pp. 121–122).

References

Abdelal, R., Herrera, Y. M., Johnston, A. I., & McDermott, R. (2009). Measuring identity: A guide for social scientists. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Rev. ed.). London and New York: Verso.

Arel, D. (2002). Language categories: Backward or forward looking. In D. I. Kertzer & D. Arel (Eds.), Census and identity: The politics of race, ethnicity, and language in national census (pp. 92–121). Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bines, C. (1998). Din istoria imigrărilor în Israel. București: Hasefer.

Blomqvist, A. (2014). Economic nationalizing in the ethnic borderlands of Hungary and Romania: Inclusion, exclusion and annihilation in Szatmár/Satu-Mare 1867–1944. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

Bodó, J., & Bartha, G. (1996). Elvándorlók? Vendégmunka és életforma a Székelyföldön. Csíkszereda: Pro-Print.

Botoş, R., Mârza, D., & Popovici, V. (2016). Censuses between population statistics and politics. The Romanian press from Hungary and the censuses between 1869 and 1910. Romanian Journal of Population Studies, 10(1), 5–18.

Brǎdǎţan, C., & Kulcsár, L. J. (2014). When the educated leave the east: Romanian and Hungarian skilled immigration to the USA. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 15(3), 509–524.

Brubaker, R. (1998). Migrations of ethnic unmixing in the “new Europe”. International Migration Review, 32(4), 1047.

Brubaker, R. (2001). The return of assimilation? Changing perspectives on immigration and its sequels in France, Germany, and the United States. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 24(4), 531–548.

Brubaker, R. (2004). Ethnicity without groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brubaker, R., Feischmidt, M., Fox, J., & Grancea, L. (2006). Nationalist politics and everyday ethnicity in a Transylvanian town. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cernat, V. (2012). Ethnic conflict and reconciliation in post-Communist Romania. In O. Simić, Z. Volčič, & C. R. Philpot (Eds.), Peace psychology in the Balkans. Dealing with a violent past while building peace (pp. 17–34). New York: Springer.

Csergő, Z., & Regelmann, A.-C. (2017). Europeanization and collective rationality in minority voting. Problems of Post-Communism, 64(5), 291–310.

Diaconescu, M. (2008). The identity crisis of Moldavian Catholics—Between politics and and historic myths. A case study: The myths of Romanian origin. In S. Ilyés, L. Peti, & F. Pozsony (Eds.), Local and transnational Csángó lifeworlds (pp. 81–93). Cluj-Napoca: Kriza János Ethnographical Society.

Emigh, R. J., & Szelényi, I. (Eds.). (2000). Poverty, ethnicity, and gender in eastern Europe during the market transition. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Faist, T. (2010). Diaspora and transnationalism: What kind of dance partners? In R. Bauböck & T. Faist (Eds.), Diaspora and transnationalism: Concepts, theories and methods (pp. 9–35). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Fassmann, H., & Münz, R. (1994). European east-west migration, 1945–1992. International Migration Review, 28(3), 520.

Fenton, S. (2003). Ethnicity. Key concepts. Cambridge and Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Finnäs, F., & O’Leary, B. (2003). Choosing for the children: The affiliation of the children of minority-majority group intermarriages. European Sociological Review, 19(5), 483–499.

Ghețău, V. (2013). Recensământul și aventure INS cu datele finale. cursdeguvernare.ro, 7 August. Available at: http://cursdeguvernare.ro/recensamantul-si-aventura-ins-prin-datele-finale.html.

Gödri, I. (2004). A magyarországra bevándorolt népesség jellemzői, különös tekintettel a Romániából bevándorlókra. In T. Kiss (Ed.), Népesedési folyamatok az ezredfordulón Erdélyben (pp. 126–147). Kolozsvár: Kriterion and RMDSZ Ügyvezető Elnökség.

Gödri, I., & Tóth, P. P. (2005). Bevándorlás és beilleszkedés. Budapest: KSH Népességkutató Intézet.

Gyurgyík, L., & Kiss, T. (2010). Párhuzamok és különbségek. A második világháború utáni erdélyi és szlovákiai magyar népességfejlődés összehasonlító elemzése. Budapest: EÖKIK.

Hirsch, F. (2004). Towards a Soviet order of things: The 1926 census and the making of the Soviet Union. In S. Szreter, H. Sholkamy, & A. Dharmalingam (Eds.), Categories and contexts: Anthropological and historical studies in critical demography (pp. 126–147). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horowitz, D. L. (1985). Ethnic groups in conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Horváth, I. (2004). Az erdélyi magyar fiatalok Magyarország irányú tanulási migrációja 1990–2000. Erdélyi Társadalom, 2(2), 59–84.

Horváth, I. (2005). Erdély és Magyarország közötti migrációs folyamatok. Kolozsvár: Scientia.

Horváth, I., & Kiss, T. (2015). Depopulating semi-periphery? Longer term dynamics of migration and socioeconomic development in Romania. Demográfia English Edition, 58(5), 91–132.

Horváth, I., & Kiss, T. (2017). Ancheta experților locali privind situația romilor pe unități administrativ-teritoriale. In I. Horváth (Ed.), Raport de cercetare – SocioRoMap. O cartografiere a comunităţilor de romi din România (pp. 9–190). Cluj-Napoca: Editura Institutului pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităţilor Naţionale.

Hroch, M. (1985). Social preconditions of national revival in Europe: A comparative analysis of the social composition of patriotic groups among the smaller European nations. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ioanid, R. (2005). The ransom of the Jews: The story of the extraordinary secret bargain between Romania and Israel. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee.

Jenkins, R. (2008). Rethinking ethnicity (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kapitány, B. (2013). Kárpát-medencei népszámlálási körkép. Demográfia, 56(1), 25–64.

Kertzer, D. I., & Arel, D. (Eds.). (2002). Census and identity: The politics of race, ethnicity, and language in national census. Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kligman, G. (1998). The politics of duplicity: Controlling reproduction in Ceausescu’s Romania. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kukutai, T., & Thompson, V. (2015). ‘Inside out’: The politics of enumerating the nation by ethnicity. In P. Simon, V. Piché, & A. A. Gagnon (Eds.), Social statistics and ethnic diversity. Cross-national perspectives in classifications and identity politics (pp. 39–61). Cham: Springer.

Ladányi, J., & Szelényi, I. (2006). Patterns of exclusion: Constructing Gypsy ethnicity and the making of an underclass in transitional societies of Europe. New York: Columbia University Press.

Laitin, D. D. (1995). Marginality: A microperspective. Rationality and Society, 7(1), 31–57.

László, M., & Novák, C. Z. (2012). A szabadság terhe. Marosvásárhely, március 16–21, 1990. Csíkszereda: Pro-Print.

Lee, R. (2004). Reflections on inverse projection. Its origins, development, extensions and relation to forecast. In E. Barbi, S. Bertino, & E. Sonnino (Eds.), Inverse projection techniques: Old and new approaches (pp. 11–27). Berlin and New York: Springer.

Longman, T. (2001). Church politics and the genocide in Rwanda. Journal of Religion in Africa, 31(2), 163–186.

McGarry, J., O’Leary, B., & Simeon, R. (2008). Integration or accommodation? In S. Choudhry (Ed.), Constitutional design for divided societies: Integration or accommodation? (pp. 41–88). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Muntele, I. (2003). Migrations internationales dans la Roumanie moderne et contemporaine. In D. Diminescu (Ed.), Visibles mais peu nombreux–: les circulations migratoires roumaines (pp. 33–51). Paris: Maison des sciences de l’homme.

Münz, R., & Ohliger, R. (2001). Migrations of German people to Germany: A light on the German concept of identity. The International Scope Review, 3(6), 60–74.

Nagy, M. Z. (2011). Kisebbségi érdekképviselet vagy pártpolitika? A Romániai Magyar Népi Szövetség története 1944–1953. Pécsi Tudományegyetem: Doktori disszertáció.

Papp, A. Z., & Márton, J. (2014). Peremoktatásról varázstalanítva. A Csángó Oktatási Program értékelésének tapasztalatai. Magyar Kisebbség, 19(2), 7–32.

Rallu, J.-L., Piché, V., & Simon, P. (2006). Demography and ethnicity: An ambiguous relationship. In G. Caselli, J. Vallin, & G. J. Wunsch (Eds.), Demography: Analysis and synthesis; A treatise in population studies (pp. 531–549). Amsterdam and Boston: Elsevier.

Regényi, E., & Törzsök, E. (1988). Romániai menekültek Magyarországon 1988. In Medvetánc. Jelentések a határokon túli magyar kisebbségek helyzetéről. Csehszlovákia, Szovjetunió, Románia, Jugoszlávia (pp. 187–241). Budapest: Elite.

Rughiniş, C. (2010). The forest behind the bar charts: Bridging quantitative and qualitative research on Roma/Tigani in contemporary Romania. Patterns Prejudice, 44(4), 337–367.

Rughiniş, C. (2011). Quantitative tales of ethnic differentiation: Measuring and using Roma/Gypsy ethnicity in statistical analyses. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(4), 594–619.

Sandu, D. (2005). Comunităţile de Romi din România. O hartă a sărăciei comunitare prin sondajul PROROMI. București: Banca Mondială.

Sandu, D. (2006). Locuirea temporară în străinătate: Migrația economică a românilor: 1990–2006. București: Fundația pentru o Societate Deschisă.

Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Seres, A., & Egry, G. B. (2011). Magyar levéltári források az 1930. évi Romániai népszámlálás nemzetiségi adatsorainak értékeléséhez. Kolozsvár: ISPMN and Kriterion.

Simon, P. (2008). The choice of ignorance: The debate on ethnic and racial statistics in France. French Politics, Culture & Society, 26(1), 7–31.

Simon, P. (2012). Collecting ethnic statistics in Europe: A review. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35(8), 1366–1391.

Simon, P. (2017). The failure of the importation of ethno-racial statistics in Europe: Debates and controversies. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(13), 2326–2332.

Stroschein, S. (2012). Ethnic struggle, coexistence, and democratization in eastern Europe. Cambridge studies in contentious politics. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Szentannai, Á. (2001). A Magyarországon tanult fiatalok karrierkövetése. Regio, 12(4), 113–131.

Szilágyi, N. S. (2002). Észrevételek a romániai magyar népesség fogyásáról, különös tekintettel az asszimilációra. Magyar Kisebbség, 7(4), 64–96.

Szilágyi, N. S. (2004). Az asszimiláció és hatása a népesedési folyamatokra. In T. Kiss (Ed.), Népesedési folyamatok az ezredfordulón Erdélyben (pp. 157–235). Kolozsvár: Kriterion and RMDSZ Ügyvezető Elnökség.

Szoke, L. (1992). Hungarian perspectives on emigration and immigration in the new European architecture. International Migration Review, 26(2), 305–323.

Tánczos, V. (2010). A moldvai csángók magyar nyelvismerete 2008–2010-ben. Magyar Kisebbség, 25(3–4), 62–156.

Tánczos, V. (2012). “Hát mondja meg kend, hogy én mi vagyok!” A csángó nyelvi identitás tényezői: helyzetjelentés a 2011-es népszámlálás kapcsán. Pro Minoritate, 16(3), 80–112.

Tompea, A., & Năstuță, S. (2009). Romania. In H. Fassmann, U. Reeger, & W. Sievers (Eds.), Statistics and reality: Concepts and measurements of migration in Europe (pp. 217–230). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Uvin, P. (2002). On counting, categorizing, and violence in Burundi and Rwanda. In D. I. Kertzer & D. Arel (Eds.), Census and identity: The politics of race, ethnicity, and language in national census (pp. 148–175). Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Varga, E. Á. (1998). Fejezetek a jelenkori Erdély népesedéstörténetéből. Budapest: Püski.

Varga, E. Á. (1999). Erdély etnikai és felekezeti statisztikája (1850–1992). Il Kötet. Csíkszereda: Pro-Print.

Waugh, L. R. (1982). Marked and unmarked: A choice between unequals in semiotic structure. Semiotica, 38(3–4), 299–318.

Wimmer, A. (2013). Ethnic boundary making: Institutions, power, networks. Oxford studies in culture and politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kiss, T. (2018). Demographic Dynamics and Ethnic Classification: An Introduction to Societal Macro-Processes. In: Kiss, T., Székely, I., Toró , T., Bárdi, N., Horváth, I. (eds) Unequal Accommodation of Minority Rights. Palgrave Politics of Identity and Citizenship Series. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78893-7_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78893-7_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-78892-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-78893-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)