Abstract

We investigated long-term outcomes (education, employment, marriage, fertility, multiple primary cancers, and psychosocial outcomes) and quality of life (QOL) in survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma. In a limb-sparing group, the proportion of survivors who graduated from a university was significantly higher. There were few problems regarding employment. The marital rates were slightly lower in male survivors and in an amputation group. Recent chemotherapy affected male survivors’ fertility. Of 162 patients, 13 had multiple primary cancers. When reviewing psychosocial outcomes, the incidence of posttraumatic stress symptom was low, and posttraumatic growth was marked. The QOL was satisfactory, excluding “physical functioning.” The limb-sparing group was more adaptable to social life activities than the amputation group.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Advances in multidisciplinary treatment for osteosarcoma have markedly improved treatment results, increasing the number of long-term survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma. In osteosarcoma treatment, an era when the purpose of treatment was to cure the disease ended, and the postcure quality of life (QOL) has been emphasized. However, few studies have examined the psychosocial outcome or QOL of long-term survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma [1].

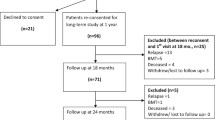

We conducted a study to comprehensively evaluate the QOL of long-term survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma. As shown in Fig. 20.1, various factors are involved. To evaluate the QOL, individual factors must be investigated.

In this chapter, we introduce long-term outcomes (education, employment, marriage, fertility, multiple primary cancers, and psychosocial outcomes) and QOL in survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma based on our study results [2–8].

2 Education and Employment

2.1 Our Report on Education [2]

In 41 survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma who were treated in our hospital between 1976 and 1995, a questionnaire survey regarding education (returning to school, educational background) was conducted. In addition, they were divided into two groups based on affected limb conditions at the time of the survey: amputation (including rotationplasty) and limb-sparing groups. The results were compared between the two groups.

Of the 41 subjects, responses were obtained from 27 (response rate, 65.9 %). These consisted of 11 males and 16 females. The mean age at the initial presentation was 13.6 years. That at the time of the survey was 34 years. The amputation group consisted of 18 subjects, and the limb-sparing group consisted of 9. The mean interval from the completion of treatment was 218 months.

Of the 27 subjects, 19 could return to school, whereas 7 could not return. There was no description in 1. In 73.1 % (19/26), it was possible to return to the former school. The educational background was senior high school in 12 subjects and university in 13. There was no description in 2. Of these subjects, 52 % (13/25) graduated from a university, being similar to the proportion of Japanese who graduate from a university (45 %). In the limb-sparing group, the proportion of survivors who graduated from university was significantly higher, suggesting that affected limb conditions influence education (Table 20.1, published from Reference [2] based on approval).

2.2 Other Reports on Education

Nagarajan et al. reported that the education level was lower in an amputation group [9]. Novakovic et al. indicated that there was no difference in the education level between survivors and their siblings [10]. These results were similar to those of our study.

2.3 Our Report on Employment [2]

We investigated employment (occupation, annual income) in the above 27 survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma. There were 18 clerical workers, four technicians, one sales worker, and two housewives. There was no description in 2. Of these, 72 % (18/25) had clerical jobs. The mean annual income was 4,010,000 yen, being similar to that of Japanese businessmen (4,280,000 yen). There was no difference in the mean annual income between the amputation and limb-sparing groups. In Japan, laws for the handicapped have been implemented, and there were few problems regarding survivors’ employment.

2.4 Other Reports on Employment

Nagarajan et al. reported that the employment rates were higher in survivors who had received high-level education and male survivors, and that there was no difference in the employment rate between amputation and limb-sparing groups [9]. Hays et al. indicated that there were few financial problems in pediatric cancer patients [11]. In our study, there were also few problems regarding survivors’ employment. Nicholson et al. reported that there was no difference in the employment rate between survivors and their siblings [12]. On the other hand, Novakovic et al. emphasized that the employment rate in survivors was significantly lower [10].

3 Marriage and Fertility

3.1 Our Report on Marriage [3, 4]

In 62 survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma who were treated in our hospital between 1976 and 2002, a questionnaire survey regarding marriage was conducted. Of these, responses were obtained from 46 (response rate, 74.2 %). We investigated the marital rate (number of married survivors/total number of survivors) in the 46 survivors. In addition, they were divided into two groups: amputation and limb-sparing groups. The marital rate was examined in each group. As controls, it was investigated in 52 siblings.

Overall, the marital rate was 63.0 % (29/46). In the siblings, it was 63.5 % (33/52) (Table 20.2, Reference [4]). The marital rates were slightly lower in male survivors and in the amputation group, although there were no significant differences.

3.2 Other Reports on Marriage

Nagarajan et al. reported that the marital rate in female survivors was higher than in male survivors, and that the marital rate in survivors was lower than in their siblings. In addition, they indicated that there was no difference in the marital rate between amputation and limb-sparing groups [9]. Our study also showed that the marital rate was lower in male survivors. Novakovic et al. reported that in survivors, the marital rate was lower than in their siblings, and that the number of divorces was greater [10]. On the other hand, Nicholson et al. indicated that there was no difference in the marital rate between survivors and their siblings [12]. In our study, there was also no difference in the marital rate between survivors and their siblings.

3.3 Our Report on Fertility [3, 4]

In 29 survivors who were married, we investigated the fertility rate (number of survivors raising a child/number of married survivors). They were divided into two groups: MC group in which moderate-dose chemotherapy was performed between 1976 and 1986 and IC group in which intensive-dose chemotherapy was performed between 1987 and 2002. The fertility rate was examined in each group. As controls, it was investigated in 33 siblings.

Overall, the fertility rate was 58.6 % (17/29). In the siblings, it was 81.8 % (27/33). In male survivors, the fertility rate was slightly lower (Table 20.3, Reference [4]). In particular, the fertility rate in male survivors in the IC group was significantly lower than in male siblings (p = 0.018), suggesting that recent intensified chemotherapy for osteosarcoma affects male survivors’ fertility.

3.4 Other Reports on Fertility

Williams et al. reported that ifosfamide influenced fertility [13]. Longhi et al. indicated that ifosfamide-related infertility was more frequent in males [14]. The influence of chemotherapy on fertility is an important issue for long-term survivors; this should be further reviewed in the future.

4 Multiple Primary Cancers

4.1 Our Report on Multiple Primary Cancers

We investigated the incidence of multiple primary cancers in 162 patients with osteosarcoma who were treated in our department between 1976 and 2009, with an age of 30 years or younger on initial presentation. Nine patients with second malignant neoplasms following osteosarcoma were assigned to Group A. Four patients with osteosarcoma as a second malignant neoplasm were assigned to Group B. We examined the clinical features of these 13 patients.

In Group A, second malignant neoplasms were diagnosed as breast carcinoma in four patients, acute myelogenous leukemia in two, a malignant phyllodes tumor in one, ovarian carcinoma in one, and small intestine carcinoma in one. Ages at the development of second malignant neoplasms ranged from 14 to 34 years (mean, 25.9 years). Intervals from the development of osteosarcoma until that of second malignant neoplasms ranged from 3 to 16 years (mean, 9.6 years) (Table 20.4).

In Group B, first malignant neoplasms were diagnosed as adrenocortical cancer in one patient, malignant teratoma in one, Ewing’s sarcoma in one, and retinoblastoma in one. Ages at the time of the development of the first malignant neoplasms ranged from 0 to 10 years (mean, 3 years). Intervals from the development of the first malignant neoplasms until that of osteosarcoma ranged from 5 to 34 years (mean, 15.3 years) (Table 20.4).

In most patients in Groups A and B, high-dose anticancer drugs were used to treat the first malignant neoplasms. Anticancer treatment may have been involved in the development of the second malignant neoplasms. Li-Fraumeni syndrome is known to be in the same cancer family as osteosarcoma. Of our 13 patients, two had Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

4.2 Other Reports on Multiple Primary Cancers

Malkin et al. reported that germ cell mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene were etiologically involved in the pathogenesis of Li-Fraumeni syndrome and that the incidence of breast cancer was high [15]. According to Turaka et al.. osteosarcoma was observed in three patients in a chart review of 245 patients with retinoblastoma [16]. Goldsby et al. indicated that the incidence of second malignant neoplasms increased with the follow-up period [17]. In the future, the incidence of multiple primary cancers in osteosarcoma patients may further increase. Strict long-term follow-up may be necessary.

5 Psychosocial Outcomes

5.1 Our Report on Psychosocial Outcomes [6]

In 55 survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma who were treated in our hospital, a questionnaire survey regarding psychosocial outcomes was conducted. To evaluate psychosocial outcomes, the following questionnaires were used: For family function assessment, the Family APGAR [18] was used. For social support assessment, the SSQ-S and SSQ-N [19] were used. For posttraumatic stress symptom assessment, the IES-R [20] was used. For posttraumatic growth assessment, the PTGI [21, 22] was used. Subsequently, multiple regression analysis was performed using the IES-R and PTGI as dependent variables. Independent variables included the sex, age at diagnosis, affected limb condition (amputation/preservation), Family APGAR, SSQ-S, and SSQ-N.

Of the 55 survivors, responses were obtained from 30 (response rate, 54.5 %). They consisted of 16 in whom amputation was performed and 14 in whom the affected limb was spared. The mean Family APGAR score was 7.97, suggesting high-level family function. The mean SSQ-N and SSQ-S scores were 4.03 and 5.02, respectively, being similar to those in healthy adults. The mean IES-R score was 9.70; posttraumatic stress symptom was not frequent. The mean PTGI score was 51.8, being markedly higher than in Japanese university students (33.9). Posttraumatic growth was marked (Table 20.5, Reference [6]). In the survivors of osteosarcoma, the incidence of posttraumatic stress symptom was low, and posttraumatic growth was marked.

Multiple regression analysis with the IES-R as a dependent variable showed that only the Family APGAR was a significant independent variable. High-level family function reduced the survivors’ posttraumatic stress symptom.

Multiple regression analysis with PTGI as a dependent variable showed that the age at diagnosis, affected limb condition, and SSQ-N were significant independent variables. In patients of an advanced age and those after amputation, posttraumatic growth was marked. Social support led to the survivors’ posttraumatic growth.

5.2 Other Reports on Psychosocial Outcomes

Bressound et al. reported that a low-level family function was associated with posttraumatic stress symptom [23]. Nicholson et al. indicated that survivors’ psychosocial outcomes were favorable [12]. Michel et al. suggested that a prospective outcome occurs after pediatric cancer and that it is promoted by appropriate counseling [24]. We reported that not only survivors but also their parents showed posttraumatic stress disorder or posttraumatic growth [7]. In the future, psychosocial care for survivors may be important.

6 Evaluation of Quality of Life (QOL)

6.1 Evaluation Methods of QOL

To evaluate the affected limb function of survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma, the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society score (MSTS score) [25], Toronto Extremity Salvage Score (TESS) [26], Functional Mobility Assessment (FMA) [27], and Reintegration to Normal Living Index (RNLI) [28] are used. For QOL assessment, the Short Form-36 (SF-36) [29], TNO-AZL Questionnaire for Adult’s Quality of Life (TAAQOL) [30], TNO-AZL Child Quality of Life (TACQOL) [31], Bt-DUX [32], and Utrecht Coping List for Adolescents (UCL-A) [33] are used. For the details of respective evaluation methods, refer to the references.

6.2 Our Report on QOL [8]

In 59 survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma who were treated in our department between 1976 and 2000, a questionnaire survey regarding QOL was conducted. Of these survivors, responses were obtained from 33 (response rate, 55.9 %).

We evaluated the survivors’ QOL using the SF-36 consisting of eight subscales [29]. On global QOL assessment, the “physical functioning” score was markedly lower than the national standard value. However, the scores for the other seven subscales were higher than national standard values (Fig. 20.2, Reference [8]). The survivors’ QOL was satisfactory, excluding “physical functioning.”

QOL evaluated using SF-36. The “physical functioning (PF)” score was lower than the national standard value, but the scores for the other seven subscales were higher than the standard values. PF physical functioning, RP physical role, BP bodily pain, GH general health perceptions, VT vitality, SF social functioning, RE emotional role, MH mental health

We compared the QOL between limb-sparing and amputation groups (n = 14 and 19, respectively). In the former, the “social functioning” score was significantly higher (p = 0.023). There were no significant differences in the other seven subscales. In our study, the limb-sparing group was more adaptable to social life activities than the amputation group; the QOL was higher.

6.3 Relationship Between Affected Limb Function and QOL

We examined the relationship between the affected limb function and QOL in long-term survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma. We evaluated the survivors’ limb function using a Musculoskeletal Tumor Society score (MSTS score) [25] and investigated the correlation between the MSTS score and SF-36.

There were positive correlations among three subscales: “physical functioning,” “bodily pain,” and “social functioning.” However, there were no correlations among the other five subscales. Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between the MSTS score and “physical component summary” of SF-36. However, there was no correlation between this score and “mental component summary” of SF-36, suggesting that the QOL cannot be evaluated based on the affected limb function only. It was shown that a favorable affected limb function did not always lead to a good QOL.

6.4 Other Reports on QOL

Nagarajan et al. reported that most survivors of bone tumors were adaptable to their environments using the RNL [34]. Koopman et al. also examined the QOL using the TAAQOL, TACQOL, and UCL-A and indicated that survivors were adaptable after treatment, and that there were no long-term emotional or social problems [33]. On the other hand, Ness et al. emphasized that survivors of osteosarcoma were less active than their siblings, requiring positive support [35].

Zahlten-Hinguranage et al. reported that the long-term QOL was similar between limb-sparing and amputation groups [36]. In our study, the limb-sparing group was more adaptable to social life activities than the amputation group; the QOL was higher. Forni et al. and Veenstra et al. indicated that the QOL of patients who underwent rotationplasty was high using the SF-36 [37, 38].

Thus, many studies have suggested that survivors’ QOL is relatively favorable. However, the survivor-supporting system is not sufficient, as reported by Ness et al. [35]. In the future, it may be necessary to positively support survivors.

7 Epilogue

It is difficult to standardize the results of our study for the following reasons: This was a retrospective study; the number of patients was small; and the data were obtained from a single institution. However, our study may provide clues to QOL improvement in survivors of pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma. Lastly, issues to be improved in the future are presented.

7.1 Issue 1

Recent intensified treatment for osteosarcoma showed good results, but raised a new issue, male infertility. Strategies to resolve this issue must be established.

7.2 Issue 2

It is expected that the incidence of second malignant neoplasms in survivors of osteosarcoma will increase. Strict long-term follow-up is necessary.

7.3 Issue 3

Survivors of osteosarcoma show mental growth after treatment. The survivors’ QOL was satisfactory, excluding “physical functioning.” However, social support is still insufficient; total care must be intensified.

References

Nagarajan R, Clohisy DR, Neglia JP, et al. Function and quality-of-life of survivors of pelvic and lower extremity osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma: the childhood cancer survivor study. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1858–65.

Yonemoto T, Ishii T, Takeuchi Y, et al. Education and employment in long-term survivors of high-grade osteosaroma: a Japanese single center experience. Oncology. 2007;72:274–8.

Yonemoto T, Tatezaki S, Ishii T, et al. Marriage and fertility in long-term survivors of high grade osteosarcoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26:513–6.

Yonemoto T, Ishii T, Takeuchi Y, et al. Recently intensified chemotherapy for high-grade osteosarcoma may affect fertility in long-term male survivors. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:763–7.

Yonemoto T, Tatezaki S, Ishii T, et al. Multiple primary cancers in patients with osteosarcoma: the influence of anticancer drugs and genetic factors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:220–4.

Yonemoto T, Kamibeppu K, Ishii T, et al. Psychosocial outcomes in long-term survivors of high-grade osteosaroma: a Japanese single-center experience. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:4287–90.

Yonemoto T, Kamibeppu K, Ishii T, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptom (PTSS) and posttraumatic growth (PTG) in parents of childhood, adolescent and young adult patients with high-grade osteosarcoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2012;17:272–5.

Yonemoto T, Ishii T, Takeuchi Y, et al. Evaluation of quality of life (QOL) in long-term survivors of high-grade osteosaroma: a Japanese single center experience. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:3621–4.

Nagarajan R, Neglia JP, Clohisy DR, et al. Education, employment, insurance, and marital status among 694 survivors of pediatric lower extremity bone tumors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer. 2003;97:2554–64.

Novakovic B, Fears TR, Horowitz ME, et al. Late effects of therapy in survivors of Ewing’s sarcoma family tumors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;19:220–5.

Hays DM, Landsverk J, Sallan SE, et al. Educational, occupational, and insurance status of childhood cancer survivors in their fourth and fifth decades of life. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1397–406.

Nicholson HS, Mulvihill JJ, Byrne J. Late effects of therapy in adult survivors of osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1992;20:6–12.

Williams D, Crofton PM, Levitt G. Does ifosfamide affect gonadal function? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:347–51.

Longhi A, Macchiagodena M, Vitali G, et al. Fertility in male patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy for osteosarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:292–6.

Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, et al. Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science. 1990;250:1233–8.

Turaka K, Shields CL, Meadows AT, et al. Second malignant neoplasms following chemoreduction with carboplatin, etoposide, and vincristine in 245 patients with intraocular retinoblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:121–5.

Goldsby R, Burke C, Nagarajan R, et al. Second solid malignancies among children, adolescents, and young adults diagnosed with malignant bone tumors after 1976: follow-up of a Children’s Oncology Group cohort. Cancer. 2008;113:2597–604.

Smilkstein G, Ashworth C, Montano D. Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J Fam Pract. 1982;15:303–11.

Furukawa TA, Harai H, Hirai T, et al. Social support questionnaire among psychiatric patients with various diagnoses and normal controls. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:216–22.

Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–18.

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9:455–71.

Taku K, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, et al. Examining posttraumatic growth among Japanese university students. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2007;20:353–67.

Bressoud A, Real del Sarte O, Stiefel S, et al. Impact of family structure on long-term survivors of osteosarcoma. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:525–31.

Michel G, Taylor N, Absolom K, et al. Benefit finding in survivors of childhood cancer and their parents: further empirical support for the benefit finding scale for children. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36:123–9.

Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, et al. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;286:241–6.

Davis AM, Wright JG, Williams JI, et al. Development of a measure of physical function for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:508–16.

Marchese VG, Rai SN, Carlson CA, et al. Assessing functional mobility in survivors of lower-extremity sarcoma: reliability and validity of a new assessment tool. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:183–9.

Wood-Dauphinee SL, Opzoomer MA, Williams JI, et al. Assessment of global function: the reintegration to normal living index. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69:583–90.

Fukuhara S, Ware JE, Kosinski M, et al. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity of the Japanese SF-36 health survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1045–53.

Fekkes M, Kamphuis RP, Ottenkamp J, et al. Health-related quality of life in young adults with minor congenital heart disease. Psychol Health. 2001;16:239–50.

Theunissen NC, Vogels TG, Koopman HM, et al. The proxy problem: child report versus parent report in health-related quality of life research. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:387–97.

Bekkering WP, Billing L, Grimer RJ, et al. Translation and preliminary validation of the English version of the DUX questionnaire for lower extremity bone tumor patients (Bt-DUX): a disease-specific measure for quality of life. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:353–9.

Koopman HM, Koetsier JA, Taminiau AH, et al. Health-related quality of life and coping strategies of children after treatment of a malignant bone tumor: a 5-year follow-up study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:694–9.

Nagarajan R, Mogil R, Neglia JP, et al. Self-reported global function among adult survivors of childhood lower-extremity bone tumors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:59–65.

Ness KK, Leisenring WM, Huang S, et al. Predictors of inactive lifestyle among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer. 2009;115:1984–94.

Zahlten-Hinguranage A, Bernd L, Ewerbeck V, et al. Equal quality of life after limb-sparing or ablative surgery for lower extremity sarcomas. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1012–4.

Forni C, Gaudenzi N, Zoli M, et al. Living with rotationplasty–quality of life in rotationplasty patients from childhood to adulthood. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:331–6.

Veenstra KM, Sprangers MA, van der Eyken JW, et al. Quality of life in survivors with a Van Ness-Borggreve rotationplasty after bone tumour resection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;73:192–7.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Shin-ichiro Tatezaki and Dr. Kiyoko Kamibeppu, for their invaluable advice. The authors also thank the members of the Chiba Cancer Center and the Chiba Pediatric Orthopaedic Group (CPOG), for their encouragement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer Japan

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Yonemoto, T., Iwata, S., Kamoda, H., Ishii, T. (2016). Long-Term Outcomes and Quality of Life (QOL) in Survivors of Pediatric and Adolescent Osteosarcoma. In: Ueda, T., Kawai, A. (eds) Osteosarcoma. Springer, Tokyo. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55696-1_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55696-1_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Tokyo

Print ISBN: 978-4-431-55695-4

Online ISBN: 978-4-431-55696-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)