Abstract

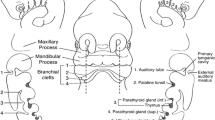

During the fourth to eighth weeks of gestation, four pairs of branchial arches and their intervening clefts and pouches are formed. Congenital branchial cysts and sinuses are remnants of these embryonic structures that have failed to regress completely. Treatment of branchial remnants requires knowledge of the related embryology. The first arch, cleft, and pouch form the mandible, the maxillary process of the upper jaw, the external ear, parts of the Eustachian tube, and the tympanic cavity. Anomalies of the first branchial pouch are rare. Sinuses typically have their external orifice inferior to the ramus of the mandible. They may traverse the parotid gland, and run in close vicinity to the facial nerve in the external auditory canal. Cysts are located anterior or posterior to the ear or in the submandibular region. They must be distinguished from preauricular cysts and sinuses, which are ectodermal remnants from an aberrant development of the auditory tubercles, tend to be bilateral, and are localized anterior to the tragus of the ear. These sinuses are blind, ending in close vicinity of the external auditory meatus.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

During the fourth to eighth weeks of gestation, four pairs of branchial arches and their intervening clefts and pouches are formed. Congenital branchial cysts and sinuses are remnants of these embryonic structures that have failed to regress completely. Treatment of branchial remnants requires knowledge of the related embryology. The first arch, cleft, and pouch form the mandible, the maxillary process of the upper jaw, the external ear, parts of the Eustachian tube, and the tympanic cavity. Anomalies of the first branchial pouch are rare. Sinuses typically have their external orifice inferior to the ramus of the mandible. They may traverse the parotid gland, and run in close vicinity to the facial nerve in the external auditory canal. Cysts are located anterior or posterior to the ear or in the submandibular region. They must be distinguished from preauricular cysts and sinuses, which are ectodermal remnants from an aberrant development of the auditory tubercles, tend to be bilateral, and are localized anterior to the tragus of the ear. These sinuses are blind, ending in close vicinity of the external auditory meatus.

The most common branchial cysts and sinuses derive from the second branchial pouch, which forms the tonsillar fossa and the palatine tonsils. The external orifice of the sinus can be located anywhere along the middle to lower third of the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The sinus penetrates the platysma and runs parallel to the common carotid artery, crosses through its bifurcation, and most commonly exits internally in the posterior tonsillar fossa. A complete sinus may discharge clear saliva. A cyst, as a remnant of the second branchial pouch, presents as a soft mass deep to the upper third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The depth distinguishes it from cystic hygromas, which are located in the subcutaneous plane.

The third arch forms the inferior parathyroid glands and the thymus, whereas the fourth arch migrates less far down and develops into the superior parathyroid glands. Sinuses of the third arch open externally in the same region as those of the second one, but run upward behind the carotid artery to the piriform fossa. Cystic remnants may compress the trachea and cause stridor. Sinuses and cysts of the fourth branchial arch and cleft are extremely rare. Remnants of both the third and fourth arches most commonly present as inflammatory, lateral neck masses, more often on the left side. The cyst may evoke a false impression of acute thyroiditis. CT scans of the neck help to identify the origin of such lesions. In an acute suppurative phase, external pressure onto the mass may result in laryngoscopically visible evacuation of pus into the piriform fossa.

Cystic remnants present commonly in adolescence and adulthood, whereas sinuses and fistulas are usually seen in infancy and early childhood. In principle, regardless of the patient’s age, clinical manifestation should be taken as an indication for elective excision before complications—mainly of an inflammatory nature—supervene (Figs. 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4 and 2.5).

For excision of the most common second branchial pouch remnant, the patient is placed in a supine position. Following induction of general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation, the head is turned to the side. A sandbag is placed beneath the shoulders to expose the affected side. Instillation of methylene blue into the orifice aids identification of the sinus during dissection. Some surgeons introduce a lacrimal duct probe into the orifice to guide dissection of the tract

Subcutaneous tissue and platysma are divided until the sinus tract is reached; the tract is easily palpable when the traction suture is gently tensed. Mobilization of the sinus continues in a cephalad direction as far as possible with gentle traction. The operation can usually be done through a single elliptical incision by keeping traction on the sinus tract; the anaesthetist places a gloved finger to push the tonsillar fossa downwards. Dissection then continues through the carotid bifurcation to the tonsillar fossa. Close contact with the sinus is obligatory to avoid any injury to the arteries or the hypoglossal nerve. Close to the tonsillar fossa, the sinus is ligated with a 5/0 absorbable transfixation suture and is divided

For first branchial pouch remnants, the opening of the fistula is circumcised with an elliptical skin incision. Careful dissection liberates the subcutaneous layer of the embryological remnant, which is now transfixed with a stay suture. This suture is used for traction on the duct, which facilitates its identification on subsequent dissection into the depth towards the auditory canal. Because the tract is in intimate contact with the parotid gland and may be very close to the facial nerve, dissection must stay close to the tract, and electrocoagulation—exclusively bipolar—must be used sparingly. A neurosurgical nerve stimulator may be employed to identify and preserve fine nerve fibers. The opening of the fistula to the external ear canal should be included into the resection to avoid recurrence. The subcutaneous tissue is approximated using 5/0 absorbable sutures, followed by interrupted subcuticular absorbable 6/0 sutures

2.1 Results and Conclusions

Recurrences are most likely due to proliferation of residual epithelium from cysts or sinuses. The surgical procedure should thus be performed electively soon after diagnosis. Infected cysts and sinuses are treated with antibiotics until the inflammatory signs subside, unless abscess formation mandates incision and drainage. Repeated infections render identification of the tissue layers much more difficult. Surgery after infections of remnants of the first branchial pouch carries an increased risk of facial nerve injury. To avoid damage to vital vascular and nerve structures, it is important to keep dissection close to the sinus tract.

Suggested Reading

El Gohary Y, Gittes G. Congenital cysts and sinuses of the neck. In: Puri P, editor. Newborn Surgery. 3rd ed. London: Hodder Arnold; 2011.

Magdy EA, Ashram YA. First branchial cleft anomalies: presentation, variability and safe surgical management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:1917–25.

Nicoucar K, Giger R, Jaecklin T, Pope HG Jr, Dulguerov P. Management of congenital third branchial arch anomalies: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142:21–28.e2.

Nicoucar K, Giger R, Pope HG Jr, Jaecklin T, Dulguerov P, et al. Management of congenital fourth branchial arch anomalies: a review and analysis of published cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1432–9.

Sadler TW. Langman’s medical embryology. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

Waldhausen JHT. Branchial cleft and arch anomalies in children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15:64–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Höllwarth, M.E. (2019). Branchial Cysts and Sinuses. In: Puri, P., Höllwarth, M. (eds) Pediatric Surgery. Springer Surgery Atlas Series. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56282-6_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56282-6_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-662-56280-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-662-56282-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)