Abstract

Consumers regularly make decisions. Some of these decisions are relatively simple, such as a selecting a jam or a coffee, where the choice is entirely subjective. Others, such as investment decision-making, are risky, complex, consequential and there is a normatively optimal choice. Seeking advice from an expert is a reasonable solution in these circumstances and yet a minority of investors turn to a professional for advice. As an alternative to human advisors, technology is increasingly being harnessed to provide effective and low-cost advice to assist consumers in making decisions. In a retail context, these are shop bots and search engines often used on a mobile phone while shopping. In an investment context, these are frequently referred to as “robo-advisors”. Examining consumer intention to seek advice in an investment context, the current study demonstrates that, among numerous factors examined, unfounded confidence was the best indicator of consumer reluctance to seek advice. Robo-advisors, as artificial intelligence agents providing financial literacy instruction and impartial expert advice, may offer a solution.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Consumer decision-making regarding investments is an exemplary empirical context to study computer-based advice since investing is a complex, risky and consequential decision. These types of decisions cause uncertainty [1] and anxiety [2] and advice is a reasonable solution. An additional characteristic recommending investment decision-making as a context for studying advice is the fact that there is an objective and normatively optimal decision that maximizes investment returns for any given level of risk [3] in contrast with a low-risk inconsequential decision, (e.g. a subjective preference regarding jam or coffee) where it is difficult to argue that one decision is superior to another. With a normative ideal, the ability of an advisor to enhance decision-making outcomes can be evaluated objectively.

Investment decisions are clearly important since worries over money are the primary cause of stress in America [4]. Investing has become more relevant for a larger segment of society with accumulation of wealth in financial assets and increased participation in pension plans [5]. At the same time, the proliferation of investment products and financial innovation makes investment decision-making more difficult [6]. Seeking advice from an expert is one means of coping. When shopping, consumers often turn to store employees for assistance [7] and subsequently feel increased loyalty and choice satisfaction [8]. In an investment context, consumers enjoy benefits from expert advice by making more normatively optimal decisions that deliver superior investment returns with lower risk [9] and reduced stress [10]. Surprisingly, only 23% of working Americans and just 28% of retired Americans sought investment advice from a professional. Unfortunately, fewer still subsequently followed the advice [11]. Those most in need of advice were also those least likely to seek advice [12]. This pattern is puzzling. Despite the apparent benefits of advice in general and the curious hesitance to seek advice, understanding the decision to seek advice has not been studied and is an important gap in theory regarding consumer behavior [13].

A recent development in retail investment advisory services is the introduction of artificial intelligence to provide investment advice. Robo-advisors are computer applications that offer investment advice. Whereas human financial advisors are perceived as being expensive and subject to conflict of interest since their advice is influenced by own their compensation, robo-advisors are less expensive and less subject to conflict of interest since their compensation is product-neutral. As such, robo-advisors are likely to be very useful in assisting investors in making superior investment decisions [14].

Given the importance of investment decision-making to consumers’ emotional and financial well-being and given the reluctance of consumers to seek financial advice from a human advisor, the question arises as to how investors will respond to offers of advice from a computer. Investment decision-making is an ideal context to study advice-seeking since there is a normatively optimal choice as opposed to merely a subjective preference and therefore the benefits of advice can be clearly identified. Understanding investment advice-seeking goes beyond intellectual curiosity and theory-building to addresses a serious risk to the wealth and happiness of large segments of society. The question of interest is: What factors are more or less likely to influence a consumer decision to seek advice from a robo-advisor?

2 Theoretical Background

The general consensus within the behavioral finance literature is that investors are subject to numerous emotional and cognitive biases (e.g. overconfidence) as well as limitations in cognitive ability [15]. Professional financial advisors offer a solution to the challenges of investment decision-making. When advice is sought and followed, the result is improved financial outcomes [16]. In examining how advice improves outcomes, Bluethgen et al. [17] attribute the results to improved preference identification, enhanced information search, and correction of cognitive errors and biases by the expert advisor.

In consideration of the apparent benefits, consumer reluctance to seek advice needs to be understood. Milner and Rosenstreich [18] identify a need for more research into financial decision-making and the factors affecting decisions regarding advice-seeking in particular. While research regarding the antecedents to advice-seeking is limited, there are some indications of likely factors that may influence the decision. As a complex, risky and consequential decision, there is an opportunity for advice to enhance decision-making. Morrin et al. [19] observed that some decisions, such as investing for retirement, are inherently more difficult due to the consequential nature of the decision. Leonard-Chambers and Bogdan [20] found that advice is perceived as a solution to the difficulty of the decision, therefore perceived difficulty is likely a factor influencing the decision regarding advice. Kimiyaghalam et al. [21] found that risk tolerance is associated with advice-seeking. While advice assists choosers facing difficult decisions, there are also indications that advice can be seen as a loss of control and a threat to self-esteem [22]. Countering this loss of personal agency, self-determination theory [23] suggests feelings of self-determination may not be compromised since individuals may recognize the positive benefits and choose to exercise their personal agency through a proxy (i.e. their advisor). Although there are conflicting perspectives, self-determination is likely to affect a decision regarding advice. Chooser expertise is also a likely factor but, contrary to the tempting notion that only novices need advice, Robb et al. [24] suggest that financial literacy and expertise are associated with more rather than less advice-seeking. Similarly, a study by Van Rooij et al. [25] suggests a role for confidence with more-confident rather than less-confident investors seeking advice. Bluethgen et al. [17] found that advice is associated with increased ability to identify preferences with those more able to identify preferences also more likely to seek advice. Finally, satisfaction with prior financial decisions will likely have an effect on the decision to seek advice. Grable and Joo [26] found that those with higher levels of satisfaction with prior financial decisions are also more likely to seek advice.

Extant research therefore suggests a number of potential factors that should be examined as possible factors affecting the decision to seek investment advice. The current study considers decision difficulty, perceived risk, self-determination, financial literacy, subjective expertise (hereafter referred to as expertise for brevity), ability to identify investment preferences, and decision-making satisfaction.

Of particular interest in the current study is the relationship between financial literacy, expertise and confidence. With investment decision-making being relatively infrequent and since the results of investment decisions are only known at some future point, individuals have few opportunities to receive an objective assessment of their own financial literacy. It is therefore entirely possible that subjective self-assessment of expertise and objective measures of financial literacy may diverge. Lusardi and Mitchell [27] found that individuals are likely to over-estimate their level of financial knowledge. The implications for risky, complex, consequential decisions are that consumers may be ill-equipped to make these decisions and unaware of their own need for advice. In what has been termed the Dunning-Kruger effect, Pennycook et al. [28] demonstrate that individuals who score lowest on the Cognitive Reflection Test tended to over-estimate their performance in advance. Individuals who scored highest, tended to underestimate their performance in advance. The proposed explanation is that those individuals who hold overly-favorable views of their decision-making ability also lack meta-cognitive awareness of their own limitations.

In the context of investment decision-making, individuals with lower financial literacy would benefit most from advice but may also be less likely to seek advice since they may over-estimate their own expertise. This divergence between financial literacy and expertise is conceptualized as overconfidence or under-confidence. Hypothesizing that confidence will make investors less likely to seek advice from a robo-advisor, the current study considers multiple factors as independent variables affecting the decision to seek advice and examines whether overconfidence leads individuals to refuse advice.

3 Method

Participants were tasked with allocating a hypothetical investment portfolio over a highly representative list of fifty equity and fixed income mutual funds drawn from the Morningstar mutual fund database. One hundred and seventy-one participants who were enrolled in a four-year Bachelor of Commerce program at a Canadian University volunteered for a student research pool experiment on investment decision-making. The respondents were not aware of the purpose of the study. Information regarding the investment choices included 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year returns for investment performance as well as standard deviation as a measure of risk. Fund names were disguised to avoid confounds resulting from brand awareness. Instead, fund names reflected the type of fund. For example, “Global Equity Fund” or “Short Term Bond Fund”. The respondents considered the list of fifty funds and allocated their investment over the funds they selected. They were then offered advice in reviewing their investment decisions.

Respondents subsequently answered questions regarding their decision-making. From their responses, indexes were created for each of the factors and reliability was assessed with exploratory factor analysis using SPSS version 25. A perceived risk index was created from four items adapted from Cooper et al. [29] (Cronbach’s alpha (α) = .71). Five items creating an index for decision difficulty (α = .75), four items creating an index for self-determination (α = .80), three items creating an index for self-assessed expertise (α = .81), three items creating an index for confidence (α = .87), and three items creating an index for preference identification (α = .90) were adapted from Lewis and Gill [30]. A single item measured satisfaction with the decision-making process.

In addition to self-assessed subjective expertise in investment decision-making above, respondents were also administered an objective test of their actual investment expertise or ‘financial literacy’. The financial literacy questions were typical of basic financial literacy questions from the Rand American Life panel [31]. The questions were relatively simple such as, “Investments that are riskier tend to have lower returns over the long run.” and required an answer of “True”, “False” or “I Don’t Know”; the latter which was considered an incorrect response. The objective measure of expertise was the number of correct answers out of 10.

4 Analysis and Results

Preliminary assessment comparing Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient found a positive correlation between subjective expertise and confidence (rs = .62, p < .001). Financial literacy shows very weak correlation to confidence (rs = .06, p = .452). In turn, subjective expertise is only weakly correlated with financial literacy (rs = .32, p < .001). It is apparent that subjective assessment of one’s own expertise regarding investment decision-making is positively correlated with confidence in one’s ability to make investment decisions. In turn, financial literacy, the objective measure of investment expertise was only weakly related to both confidence and subjective expertise. These results suggest that, if respondents believed that they had expertise, they were confident even if the confidence was unfounded as indicated by low financial literacy. The confidence index noted above directly measured the extent of overconfidence. The index was created from the following questions, “I believe that I can earn above average returns compared to the overall market.”, “I believe that I can earn above average returns compared to the average financial advisor.”, and “I believe that I can earn above average returns compared to the average of my friends and family.”

A mean split divided low and high subjective expertise as well as low and high financial literacy. Cross tabulation reveals the number of cases in one of two conditions: those whose subjective self-assessment of expertise is corroborated by their objective expertise in the form of their financial literacy score; and those whose self-assessment is at odds with their financial literacy score. Table 1 below shows how the sample of N = 171 is distributed among these cases.

Those whose subjective assessment of their own expertise is at odds with their actual financial literacy are perhaps the most interesting. Those who believe they know less than they actually do have low subjective expertise and high financial literacy. Those who actually know less than they believe they do have low financial literacy and high subjective expertise. For the latter group, this “failure to recognize incompetence” [28, p. 1] manifests as unfounded confidence. These results are not atypical. A 2015 study of financial literacy found that two-thirds of global investors considered themselves to have advanced investment expertise and yet their average score on a financial literacy test was just 61% [15]. Similarly, Lusardi and Mitchell [32] found that only half of respondents were able to correctly answer simple financial literacy questions.

Hypothesizing that those with unfounded confidence will find a robo-advisor unappealing, binomial logistic regression was performed using SPSS version 25 to assess the relationship between advice-seeking behavior and confidence (M = 3.20, SD = 1.35, min = 1.00, max = 7.00) after controlling for a variety of other factors including perceived risk (M = 3.92, SD = 1.08, min = 1.00, max = 6.75), difficulty (M = 3.55, SD = .95, min = 1.00, max = 6.20), self-determination (M = 5.25, SD = 1.14, min = 2.25, max = 7.00), financial literacy (M = 5.40, SD = 1.77, min = 1.00, max = 10.00), subjective expertise (M = 3.32, SD = 1.36, min = 1.00, max = 6.33), preference identification (M = 3.75, SD = 1.25, min = 1.00, max = 7.00) and choice satisfaction (M = 4.60, SD = 1.32, min = 1.00, max = 7.00). The Box-Tidwell [33] procedure verified that the logit of the dependent variable (declining advice) is linearly related to each of the continuous independent variables. Using Bonferroni correction with testing at p < .003 [34], all 17 variables were accepted in the model.

The Hosmer Lemeshow test of goodness of fit is significant (p = .53) thus indicating that the model is not a poor fit. The logistic regression model is statistically significant χ2(9) = 27.51, p = .001. The model explains 22.0% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in accepting or refusing advice and correctly classifies 78.4% of cases. As shown in Table 2, of all the model variables, only confidence predicts whether a respondent will refuse advice (Exp(B) = 1.98, p = .002). Each unit increase in confidence makes a respondent 1.98 times more likely to refuse advice.

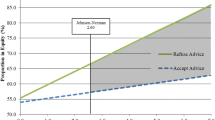

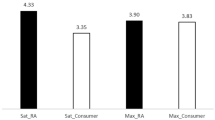

Additional analysis considered the impact of refusing advice on the quality of decision-making measured by the extent to which the resultant portfolio allocation between equities and fixed income is normatively optimal. With floodlight analysis [35], regressing the ratio invested in equities on advice decision (accepted, refused), confidence, and their interaction reveals a significant effect for confidence (t (171) = 1.98, p = .05), and no significant interaction (t (171) = −1.15, p = .25). To decompose the results, we used the Johnson-Neyman technique to identify the range(s) of confidence for which the simple effect of refusing advice is significant. Figure 1 shows the results graphically.

This analysis reveals that there is a significant increase in the proportion invested in equities by those who refuse advice versus those who accept advice for levels of confidence above 2.60. Selecting the appropriate allocation between equities and fixed income is a critical determinant of long-term success when investing. Brinson et al. [36] found that 93.6% of the differences in investment returns for individual investors can be explained by allocation between asset classes (i.e. equity, fixed income, and un-invested cash). As confidence increases, the proportion invested in equities by those refusing advice rises to 85.9% thereby creating substantial excessive risk relative to the more optimal 58.9% mean ratio of equity to fixed income of the 100 top performing pension funds in the United States [37]. With confidence, individuals are more likely to refuse advice. Furthermore, as overconfidence increased, and respondents refuse advice, the result is increasingly sub-optimal investment decision-making. Overconfident investors are taking much more risk than prudent experts recommend.

5 Discussion and Implications

Using a realistic investment decision-making scenario, the current study investigates investor reactions to the offer of advice and considers factors associated with refusing advice. Whereas low financial literacy and low expertise should ideally be associated with accepting advice, confidence, often unfounded, was the only significant factor affecting the decision to seek advice. This study demonstrates that overconfidence significantly reduces the likelihood of consumers seeking investment advice and the result is normatively sub-optimal investment decision-making with real potential for a negative impact on their long-term financial well-being.

The implications are that positioning a robo-advisor as delivering enhanced decision-making with lower cost and reduced conflict of interest substantially misses the mark among the target population. Robo-advisors would be more appealing and more effective at supporting financial well-being if they first addressed overconfidence. Willis identifies the need for personalized financial literacy training to reduce overconfidence and improve financial decision making but also describes the invasion of privacy in revealing details of “financial and emotional lives” [38, p. 431]. Colby et al. [39] identified a link between financial literacy training and shame as well as negative affect.

The private and impersonal interaction between a computer robo-advisor and a human offers an opportunity for investors to realistically assess their level of financial literacy in a comfortable setting without the embarrassment of revealing details to a human advisor. In this respect, robo-advisors have an advantage over human advisors. The financial literacy training and advice can occur at a time when they are likely to be the most beneficial – the moment when consumers are making complex, risky, and consequential investment decisions. With overconfidence addressed, investors would be more likely to avail themselves of the expert advice offered.

There are likely implications for other risky, complex, consequential decisions where advice is offered as a service. These contexts might include small business advice, legal advice, other types of financial advice such as tax planning, or advice on major purchases such a home, an automobile, or any other high-cost item. In each of these cases, it is possible that overconfidence rather than more intuitively appealing factors such as decision difficulty, complexity, or difficulty of identifying preferences will determine the decision regarding advice.

Unfounded confidence is a key factor in the inability of consumers to see value in advice. As one philosopher stated, “A little knowledge is apt to puff up and make men giddy, but a greater share of it will set them right, and bring them to low and humble thoughts of themselves” [40]. Before touting expertise, computer-based advice should first offer education to counteract overconfidence. In a private setting, after being given a better appreciation of their true level of expertise by a robo-advisor, consumers will be more willing to embrace computer-based advice and will then be more likely to make better decisions.

6 Limitations and Future Research

One potential limitation of this study is the reliance on a single respondent survey which introduces the potential for common method variance [41]. The study employs numerous procedural remedies to eliminate response cues and item context effects and also includes variation in response formats as a mitigant. It is also noted that refusing advice is a moderator of the effect of confidence on proportion invested in equites and common method variance would actually suppress any moderator effects [42] therefore the effect reported is actually, if anything, understated.

This research demonstrates the need to correct overconfidence in investment decision-making. It is also apparent that admitting the need for advice may result in feelings of shame for many consumers. It is suggested that a robo-advisor, as an inanimate artificial intelligence, may have an advantage over human advisors in providing financial literacy training to reduce overconfidence without the associated shame and negative affect. This intriguing potential benefit of human-computer interaction is worthy of future research. A future study might directly measure differences in shame, negative affect, and other outcomes within subjects and between conditions of an artificial intelligence advisor and a human advisor to establish the significance and magnitude of effects.

References

Markus, H.R., Schwartz, B.: Does choice mean freedom and well-being? J. Consum. Res. 37(2), 344–355 (2010)

Song, H., Schwarz, N.: If it’s difficult to pronounce, it must be risky: fluency, familiarity, and risk perception. Psychol. Sci. 20(2), 135–138 (2009)

Benartzi, S., Thaler, R.H.: Heuristics and biases in retirement savings behavior. J. Econ. Perspect. 21(3), 81–104 (2007)

American Psychological Association: Stress in America, Paying with our Health: American Psychological Association (2014). https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2014/stress-report.pdf

Bernheim, B.D., Garrett, D.M.: The effects of financial education in the workplace: evidence from a survey of households. J. Public Econ. 87(7), 1487–1519 (2003)

Ryan, A., Trumbull, G., Tufano, P.: a brief postwar history of US consumer finance. Bus. Hist. Rev. 85(03), 461–498 (2011)

Beatty, S.E., Mayer, M., Coleman, J.E., Reynolds, K.E., Lee, J.: Customer-sales associate retail relationships. J. Retail. 72(3), 223–247 (1996)

Reynolds, K.E., Arnold, M.J.: Customer loyalty to the salesperson and the store: examining relationship customers in an upscale retail context. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 20(2), 89–98 (2000)

Bluethgen, R., Meyer, S., Hackethal, A.: High-quality financial advice wanted! SSRN 1102445 (2008)

Financial Planning Standards Council: The Value of Financial Planning, Toronto (2013). http://www.fpsc.ca/value-financial-planning

Helman, R., Adams, N.E., Copeland, C., Van Derhei, J.: 2013 retirement confidence survey: perceived savings needs outpace reality for many. In: E. B. R. Institute (eds.) EBRI Issue Brief, no. 384 (2013)

Bhattacharya, U., Hackethal, A., Kaesler, S., Loos, B., Meyer, S.: Is unbiased financial advice to retail investors sufficient? Answers from a large field study. Rev. Financ. Stud. 25(4), 975–1032 (2012)

Brooks, A.W., Gino, F., Schweitzer, M.E.: Smart people ask for (my) advice: seeking advice boosts perceptions of competence. Manag. Sci. 61(6), 1421–1435 (2015)

Kaya, O., Schildbach, J., Deutsche Bank AG, Schneider, S.: Robo-advice–a true innovation in asset management. Deutsche Bank Research (2017). https://www.dbresearch.com/prod/dbr_internet_en-prod/prod0000000000449010/Robo-advice_-_a_true_innovation_in_asset_managemen.pdf

Centre for Applied Research: The folklore of finance. Center for Applied Research Reports, State Street Corporation (2015). http://www.statestreet.com/ideas/articles/folklore-of-finance.html

Hilgert, M.A., Hogarth, J.M., Beverly, S.G.: Household financial management: the connection between knowledge and behavior. Fed. Reserve Bull. 89, 309 (2003)

Bluethgen, R., Gintschel, A., Hackethal, A., Mueller, A.: Financial Advice and Individual Investors’ Portfolios (2008). SSRN 968197

Milner, T., Rosenstreich, D.: A review of consumer decision-making models and development of a new model for financial services. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 18(2), 106–120 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1057/fsm.2013.7

Morrin, M., Inman, J.J., Broniarczyk, S.M., Nenkov, G.Y., Reuter, J.: Investing for retirement: the moderating effect of fund assortment size on the 1/N Heuristic. J. Mark. Res. (JMR) 49(4), 537–550 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.08.0355

Leonard-Chambers, V., Bogdan, M.: Why do mutual fund investors use professional financial advisers? In: Investment Company Institute Fundamentals, vol. 16 (2007)

Kimiyaghalam, F., Safari, M., Mansori, S.: Who seeks a financial planner? A review of literature. J. Stud. Manag. Plan. 2(7), 170–189 (2016)

Usta, M., Häubl, G.: Self-regulatory strength and consumers’ relinquishment of decision control: when less effortful decisions are more resource depleting. J. Mark. Res. 48(2), 403–412 (2011)

Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M.: Self-determination theory: a macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 49(3), 182–185 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801

Robb, C.A., Babiarz, P., Woodyard, A.: The demand for financial professionals’ advice: the role of financial knowledge, satisfaction, and confidence. Financ. Serv. Rev. 21(4), 291 (2012)

Van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., Alessie, R.: Financial literacy and stock market participation. J. Financ. Econ. 101(2), 449–472 (2011)

Grable, J.E., Joo, S.-H.: A further examination of financial help-seeking behavior. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 12(1), 55 (2001)

Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O.S.: The economic importance of financial literacy: theory and evidence. J. Econ. Lit. 52(1), 5–44 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.52.1.5

Pennycook, G., Ross, R.M., Koehler, D.J., Fugelsang, J.A.: Dunning–Kruger effects in reasoning: theoretical implications of the failure to recognize incompetence. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 24(6), 1774–1784 (2017)

Cooper, W.W., Kingyens, A.T., Paradi, J.C.: Two-stage financial risk tolerance assessment using data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 233(1), 273–280 (2014)

Lewis, D., Gill, T.: Is there a mere categorization effect in investment decisions? Int. J. Res. Mark. 33(1), 232–235 (2016)

Hung, A., Parker, A., Yoong, J.K.: Defining and Measuring Financial Literacy. RAND Corporation Publications Department, Santa Monica (2009)

Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O.S.: Financial Literacy and Planning: Implications for Retirement Wellbeing: National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper No. 1078 (2011)

Box, G.E., Tidwell, P.W.: Transformation of the independent variables. Technometrics 4(4), 531–550 (1962)

Tabachnick, B.G., Fidell, L.S.: Using multivariate statistics, 6th edn. Pearson/Allyn & Bacon, Boston/Toronto (2012)

Spiller, S.A., Fitzsimons, G.J., Lynch Jr., J.G., McClelland, G.H.: Spotlights, floodlights, and the magic number zero: simple effects tests in moderated regression. J. Mark. Res. 50(2), 277–288 (2013)

Brinson, G.P., Hood, L.R., Beebower, G.L.: Determinants of portfolio performance. Financ. Anal. J. 51(1), 133–138 (1995)

Dyck, A., Lins, K.V., Pomorski, L.: Does active management pay? New international evidence. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 3(2), 200–228 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1093/rapstu/rat005

Willis, L.E.: The financial education fallacy. Am. Econ. Rev. 101(3), 429–434 (2011)

Colby, H., Erner, C., Trepel, C., Fox, C.R.: Financial Literacy Training Increases Implicit Preference for Spending 2014 Boulder Conference on Consumer Financial Decision-making (2014). https://www.encoreccri.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Financial-Literacy-poster-Boulder-2014.pdf

Taylor, A.B., William: London: printed for T. Leigh, at the Peacock in Fleetstreet; and R. Knaplock, at the Angel and Crown in St. Paul’s Church-Yard (1698)

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.-Y., Podsakoff, N.P.: Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88(5), 879 (2003)

Siemsen, E., Roth, A., Oliveira, P.: Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organ. Res. Methods 13(3), 456–476 (2010)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this paper

Cite this paper

Lewis, D. (2018). Computers May Not Make Mistakes but Many Consumers Do. In: Nah, FH., Xiao, B. (eds) HCI in Business, Government, and Organizations. HCIBGO 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10923. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91716-0_28

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91716-0_28

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-91715-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-91716-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)