Abstract

This chapter describes the concepts of entrepreneurship and institutions and reviews and categorizes the different types of institutions and entrepreneurship. After this, the factors influencing entrepreneurship are identified and classified into two categories—institutional and non-institutional. It is also known that economic, legal, managerial, educational, social, cultural, and political environments affect entrepreneurship. In this chapter, only institutional factors are taken into account, and their theoretical relationship is examined. The conclusion is that institutions are important in the entrepreneurial process. Entrepreneurs can also play an important role in the process of institutional change; thus, a bidirectional causal relationship is found between institutions and entrepreneurship. In the empirical section, the status of institutional quality, the entrepreneurial environment, and the relationship between them in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries are analysed. It is concluded that the status of these variables is inadequate and opportunity-driven entrepreneurs can create institutional changes in these countries.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In the literature on economic growth, the question has always been present: why are some countries poorer than other countries? To answer this question, several theories have been presented. In these theories, the causes, forms, and effects of economic growth are taken into consideration. In the analysis of economic growth causes, two kinds of factors are considered—proximate causes (such as the accumulation of physical and human capital etc.) and ultimate causes (such as social capital, culture, property rights, entrepreneurship etc.) [Rodrick et al. (2004), pp. 131–136; and Acemoglu (2006), pp. 83–96, Samadi (2008), pp. 11–12]. Accordingly, the attention paid to the thoughts of institutional economists grew.

Moreover, in the literature on entrepreneurship economics, the question has been present: why do some countries benefit from entrepreneurial interests while others lose? To answer this question, several theories have also been proposed in regard to the causes and effects of entrepreneurship. Accordingly, especially since the release of Baumol’s seminal paper (Baumol 1990), special attention has been paid to entrepreneurship economics. Baumol—by introducing various forms of entrepreneurship—shows that institutions are important determinants of the level and types of entrepreneurship.

Institutions and entrepreneurship are the two ultimate causes of economic growth. On the other hand institutions affect both entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs, which are considered to be the cause of institutional change. Economic growth is also considered as one of the causes of the growth of entrepreneurship. Thus, it can be stated that the triangle of institutions–entrepreneurship–economic growth is a more appropriate answer to the two questions posed in this introduction. The purpose of this chapter is to pay particular attention to the side of institutions–entrepreneurship. Also, in the present chapter, we try to answer the question: What factors influence entrepreneurial activities? What is the effect of formal and informal institutions on entrepreneurial activities? Are institutions also important in the formation of the entrepreneurial activities?

Given the special status of the MENA countries (high potential for growth and at the same time poor condition, the existence of poor institutional quality, especially state of corruption control, and the poor status of protection of property rights as well as the poor condition of entrepreneurship and poor governmental support etc.), it is very important to examine the relationship between institutions and entrepreneurship. There are many studies (e.g. Schumpeter 1934; Baumol 1990; Kozul-Wright and Rayment 1997; Busenitz et al. 2000; Yu 2001; Baez and Abolafia 2002; Westland and Bolton 2003; Spencer and Gómez 2004; Stephen et al. 2005; Li et al. 2006; Greenwood and Suddaby 2006; Lee et al. 2007; Sobel 2008; Bowen and De Clercq 2008; Aidis et al. 2009; Nyström 2008; Otahal 2012; Greener 2009; Mitchell and Campbell 2009; El Harbi and Anderson 2010; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2011; Kalantaridis and Fletcher 2012; Stenholm et al. 2013; Valdez and Richardson 2013; Dau and Cuervo-Cazurra 2014; Sambharya and Musteen 2014; Urbano and Alvarez 2014; Castaño et al. 2015; Williams and Vorley 2015; Kuchar 2016; Muralidharan and Pathak 2016; Lucas and Fuller 2017) in this field, which cover the effect of different types of institutions on the level and types of entrepreneurship.

But there are few studies (e.g. Simon-Moya et al. 2013; Fuentelsaz et al. 2015; Aparicio et al. 2016; Angulo-Guerrero et al. 2017; Brixiova and Egert 2017) on the effect of institutional factors on opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship. These studies have been conducted, respectively, for 68 countries, 63 countries over the period of 2005–2012, 43 Latin American countries during the period of 2004–2012, OECD countries over the period of 2001–2012, and 100 countries selected cross-sectionally. Aparicio et al. (2016) considers only opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, but in the other studies, both opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship types have been noted. The first contribution of this study is to consider MENA countries.

Moreover, in all studies, the effect of physical property rights (as a sub-index of economic freedom index) on opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship has been examined. Accordingly, the second contribution in the present chapter is to examine the relationship between intellectual property rights and opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship.

The results of this study show that in the MENA countries and factor-driven countries, opportunity-driven entrepreneurs are able to provide an institutional change context, at least in the short run.

The rest of the chapter is organized as follows. The theoretical background—including institutional and non-institutional factors influencing entrepreneurship—is discussed in Sect. 2. Moreover, we discuss the causal link between institutions and entrepreneurship in this section. Section 3 is devoted to the research methodology. In Sect. 4, we analysis the status of entrepreneurship and its relationship with institutional quality in MENA countries. Section 5 is devoted to discussion, while Sect. 6 presents the conclusion.

2 Theoretical Background

There is no clear and single definition for certain terms. Institution and entrepreneurship are no exception. There are several definitions for institutions and entrepreneurship. Moreover, several indices and criteria have been proposed to measure them. Before examining the factors affecting the level and types of entrepreneurship (Sect. 2.2) and the relationship between entrepreneurship and institutions (Sect. 2.3), the terminology and typology of institutions and entrepreneurship are discussed in the first sub-section. The purpose of the second sub-section is to identify all the factors affecting the level and types of entrepreneurship. The main purpose of this section is to address with greater depth the relationship between institutional factors and entrepreneurship. In the third sub-section, this relationship is discussed in terms of the causal relationship. After describing the relationship between institutions and entrepreneurship, the research hypotheses are expressed.

2.1 Institutions and Entrepreneurship: Terminology and Typology

2.1.1 Institutions

Important developments occurred in the theories of economic development after World War II. Development economists in different decades have given different recommendations for developing countries:

-

1970s: Getting prices right

-

1980s: Getting macro-polices right

-

1990s: Getting Institutions right

But what is an institution? What are the types of institutions? What are different schools of thought of institutional economics? These are the questions that are briefly answered in this sub-section.

The term institution was used by Batista in 1725 for the first time. This term in recent years has entered sociology, political science, management, psychology, history, geography, philosophy, and anthropology. But the first attention of economists to institutions can be attributed to the members of the German historical school—especially Schmöller (1840). The spark of the formation of institutional economics was also given in 1898 by Veblen. About the concept of institutions in the literature on institutional economics, there is a lack of clarity and no consensus. Institutional economists such as Veblen, Commons, Hamilton, Ruttan and Hayami (1984), Williamson (2000), North (1990, 2005), Dopfer (1991), Nelson and Sampat (2001), Acemoglu et al. (2003), Rodrik et al. (2004), Chong and Zanforlin (2004), Searle (2005), Brown (2005), Hodgson (2006), Aoki (2007), and Mitchel have addressed the terminology of the concept of institution and have provided a definition for it.

The definitions provided by the researchers have certain similarities and differences. The researchers’ attention in most definitions (e.g. Ruttan and Hayami 1984; North 1990, 2005; Dopfer 1991; Chong and Zanforlin 2004; Aoki 2007) is focused on social interaction. The second similarity in most definitions (such as North 1990) is the focus on uncertainty and the role of institutions in reducing it.

But the disagreement between the authors can be found in their main definition ground. Some economists (e.g., Williamson 2000; Ruttan and Hayami 1984; North 1990) consider the transactions between economic agents, while others consider the authority and control of economic agents. Some economists consider reaching an agreement and coordination on issues of interest.

Some institutional economists use the term institution to refer to ‘standardized behaviour pattern’, while others use it to refer to the factors and forces (such as belief norms and systems, rules of the game, and governance structure) that support or restrict customary patterns. Some authors define institutions in terms of the broader social and cultural fields and others in terms of the factors related to certain behaviour patternsFootnote 1 (Nelson and Sampt 2001).

Scholars like North (1990) consider institutions as norms or rules (of the game), while others like Aoki (2007) consider them as the result of the balance of a game. Also, Yu (2001, p. 225) define institutions as ‘the economy’s total stock of knowledge’.

To avoid some mistakes in the terminology of the term institution, Lin and Nugent (1995, p. 1307) believes that a distinction should be made between institutional arrangement (a set of structural rules that govern the behaviour of individuals in a certain range) and the institutional structure (the totality of institutional arrangements, including organizations, regulations, customs, and ideology).Footnote 2 These researchers believe that the term, considered by economists, is mainly related to institutional arrangements. From their point of view, when the term institutional change is used, it mainly refers to a change in the institutional arrangement rather than in the institutional structure.

North considers institutions as ‘rules of the game in society’ (1990, p. 19), composed of ‘informal constraints such as fines, sanctions, customs, traditions and code of conducts, and formal rules such as constitution, rules, and property rights. Also, he defines institutions as restrictions imposed by human beings on the interaction among them. In this definition, he uses restrictions instead of rules, while in 1997 (North 1997, p. 6), he used the rules of the game.

Nelson and Sampt (2001, p. 3) also defines institutions as social technologies in the operation of productive activities. These two definitions (North 1990; Nelson and Sampat 2001) are considered in this chapter.

There are several categories of institutions. In a general classification, institutions can be divided into three categories—social institutions (such as family institutions, governmental institutions, religious institutions, and educational institutions), economic institutions (such as property rights and contracts), and political institutions including the government form (such as democracy, dictatorship, monarchy, republic, aristocracy, theocracy, and oligarchy) and the restrictions imposed on politicians, the political elite, etc. (Acemoglu et al. 2005, p. 391).

Another category is given by Manger. He classifies institutions as designed and un-designed (Yu 2001). From the perspective of Longloise, institutions can also be pragmatic or organic (ibid., p. 233). But Bowen and De Clercq (2008) classifies institutions as proximate (or formal) and background (or informal). The conventional classification in institutional economics—formal and informal institutions—is considered in this chapter. These classifications and some examples are given in Table 1.

There are several classifications of institutionalism. Conventional classifications are original (old) institutionalism (including the works of Veblen, Commons, Mitchel, Ayres, etc.) and New Institutionalism (including historical, rational choice, and sociological or organizational institutionalism). Some researchers have also mentioned New Old, cognitive, and discursive institutionalism.

From the above, it is clear that in any institutional analysis, the intellectual concepts, types, and schools should be considered.

2.1.2 Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is a multidimensional, multilevel, and interdisciplinary concept and phenomenon. The term entrepreneurship was introduced for the first time by Cantillon in 1775. The use of this concept in economics has a long history and dates back to J. B. Say. After economics, it has been taken into consideration in other disciplines as well, such as history, psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Entrepreneurship in economic literature was forgotten for a long time.Footnote 3 But with the pioneering work of Schumpeter (1934), it once again became the centre of economic analyses. Baumol (1990) wrote his seminal paper focussing on types (rather than levels) of entrepreneurship and presented discussions on the factors influencing it.

For a detailed understanding of the concept and factors influencing entrepreneurship, the following criteria should be considered:

-

1.

The level of analysis: macro or micro (individuals and firms)

-

2.

The level and type (or nature) of entrepreneurship

-

3.

The environment of entrepreneurial activity (public or private sectors, formal or informal sectors)

-

4.

The role and behaviour of entrepreneurs in the development process

-

5.

The framework of the study

-

6.

Modelling approaches

When an entrepreneur is seen at the micro level, his/its (individual’s or firm’s) cognitive ability and performance is emphasized. But at the macro level, people’s decisions about investing in the venture are considered. Also, in terms of the nature or types, there are a variety of entrepreneurship. There are several types of entrepreneurship, as mentioned in Table 1.Footnote 4 The fact that an entrepreneur works in the public sector or the private sector, or that he has economic activities in the formal sector or in the informal sector, leads to several functions and tasks and different definition. Entrepreneurs play several roles in economic development process and have several positions. Wennekers and Thurik (1999) points out the roles that the entrepreneur plays in economic theory. Naudé (2010) classifies all types and definitions in three groups: behavioural, occupational, and outcomes. Footnote 5 Some important classifications and types of entrepreneurship are given in Table 1. Entrepreneurship can also be studied in the frameworks of Evolution, Development, and Population Models. Footnote 6 Also, entrepreneurial behaviours can be modelled through several approaches, such as Equilibrium, Entry/Exit, and Unified.Footnote 7

But is what entrepreneurship and who is an entrepreneurFootnote 8? It is clear from the above that no certain, united, and identical definition of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial talents and efforts can be presented. But the common aspect of definitions can be found. Entrepreneurship is an economic activity in which the entrepreneur searches for ‘discovery, creation, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities based on his motivation and ability. All these activities lead to the introduction of new products and services and organizing markets, processes, and raw materials’ (Nelson 1984; Cuervo et al. 2007; Parker 2004).

Here, brief definitions of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship and necessity-driven entrepreneurship are presented. From the perspective of Naudé (2010), these two types of entrepreneurship fall in the occupational category. Baumol (1990)‘s conventional categories of entrepreneurs (i.e. productive, unproductive, and destructive) fall in the outcome category. The definition given by Schumpeter (1934) is related to the behavioural category.

Opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is based on recognizing and exploiting good business opportunities. But necessity-driven entrepreneurship is formed due to the lack of proper job opportunities. Thus, opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is productive entrepreneurship while necessity-driven entrepreneurship is unproductive entrepreneurship (Veciana and Urbano 2008; Veciana 2007; McMullen et al. 2007).

It should be noted that there is no certain boundary between the presented definitions and different types of entrepreneurship. For example, Van der Steen and Groeneweger (2009) distinguishes between institutional, policy, and political types of entrepreneurship, but Henrekson and Sanandaji (2011) considers them as identical.

Some proxy variables for institutions and entrepreneurship are presented in Table 2.

2.2 Determinants of Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is found in all communities, races, colours, religions, and economic and social conditions; it is not related to the resources available in the country. So, we are not talking about its presence or absence. The important thing is that the level and types (or nature) of entrepreneurship are not identical across societies or even within a society across time. Therefore, the speed and intensity of its growth and its effect on social performance and welfare are presented. However, to the question of which factors affect the level and types of entrepreneurship, there is no clear answer in the literature. These factors are different, depending on the level of analysis, the nature and types of entrepreneurship, and different environments.

The level (potential and actual) and type of entrepreneurship at each of these levels are influenced by various factors. The factors affecting the possibility of potential entrepreneurs to become actual entrepreneurs (changes in levels of entrepreneurship) are different from the factors affecting the choice of various activities by potential entrepreneurs (changes in the type of entrepreneurship). Some people—regardless of the choice of entrepreneurship type—attempt to describe the factors affecting the level of entrepreneurship. Many others (such as Baumol 1990)—given the level of entrepreneurship—analyse factors affecting the choice of entrepreneurship type (productive, unproductive, and destructive, or other classifications mentioned in Table 1). A more complicated mode is that we are seeking to analyse the factors that simultaneously influence the level and type of entrepreneurship. This involves determining whether new people are added to the group of actual entrepreneurs or not, and if added to this group, what type of entrepreneurship is followed.

There are several classifications in the literature. Some of the most important classifications are:

-

1.

Economic, technological, demographic, cultural, and institutional variables

-

2.

Economic, technological, demographic, social/cultural, and policy determinants (e.g., Bosma et al. 2005)

-

3.

Economic, sociological, and psychological factors (Djankov et al. 2005; Ngunjiri 2010)

-

4.

Economic, social, and cultural factors (Castaño et al. 2015)

-

5.

Supply-side, demand-side, governance quality, and culture (Thai and Turkina 2014)

-

6.

The regulatory, normative, and cognitive/cultural pillars of institutionalization) [introduced by and adapted by: Busentiz et al. (2000), Spencer and Gómez (2004), Eunni (2010), Simon-Moya et al. (2013), Valdez and Richardson (2013), Urbano and Alvarez (2014), Sambharya and Musteen (2014)], the conducive dimension—a “fourth institutional pillar” [− introduced by: Stenholm et al. 2013]

-

7.

Macro- or national environment (economic, institutional, regulation, culture, social) and Micro-environment (social capital, ….)– Krzyzanowska (2008).

Another classification is given in Fig. 1. According to Fig. 1, the types of entrepreneurship are affected by different environments such as the legal environment (including property rights, rule of law, independence of the judiciary, etc.), economic environment (such as transaction costs, unemployment, inflation, etc.), political environment (e.g. the quality of governance, corruption, rent-seeking, etc.), social and cultural environment (such as social capital at the macro-and micro-level etc.), educational environment (such as the level of education and training in entrepreneurial skills and in general the country’s educational system), and managerial environment (such as knowledge and technology management, etc.).

In Table 3, these environments have been placed in two categories—economic and institutional factors. These variables are the ones used in most studies. There is no possibility to explain the effects of all environments on all types of entrepreneurial efforts (Table 1) at all levels. Accordingly, in the next section, based on the purpose of the present chapter, only the effect of the legal environment on entrepreneurship is described.

2.3 The Causal Link Between Institutions and Entrepreneurship

2.3.1 The Effect of Institutions on Level and Types of Entrepreneurship

Every society is faced with a series of institutional opportunities. Institutions are points on the set of opportunities, and this is the history that forms a set of individuals’ social choices. Social choices, in turn, form institutional opportunities. The politics and political institutions of a society are involved in these choices. Thus, we can say that political and social institutions—in addition to economic institutions—play a major role in the choices of individuals. One of these choices is related to the issue of entrepreneurship and individuals’ choice of entering or not entering entrepreneurial activities. If they choose to enter, it is related to productive or unproductive activities. Therefore, the institutional environment (from entrepreneurship perspective) is important (Amoros Espinosa, 2009; Estrin et al. 2013; Acs et al. 2008). The environments are shown in Fig. 1. These environments—in the form of formal and informal institutions respectively—directly and indirectly affect the economic behaviour of entrepreneurs. There is no possibility to explain the effect of all environments on all types of entrepreneurship at all levels. Accordingly, in the present chapter, only the effect of the legal environment on entrepreneurship is considered.

The effect of institutions on the level and types of entrepreneurship can be described through four channels—reducing uncertainty, reducing transaction costs, legitimizing entrepreneurial activities, and supporting against expropriation of rents. According to North, institutions are rules of the game in the society. The rules of the game have created practical limits on individuals and reduced their behaviour complexity. Due to the reduced complexity, the risk of opportunistic behaviour, uncertainty, and transaction costs are reduced.

On the other hand, institutional setup affects the structure of the individuals’ incentives. Entrepreneurs and other individuals in a society face an incentive structure. They are looking to make a profit. Also, one of the duties of entrepreneurs is discovery. The discovery process also relies on profits. The rules of the game in the field (institutions) are like the social structure of rewarding. If the rules of the game are such that profits are possible via unproductive activities, it is natural that entrepreneurs will have less incentive to enter productive activities, and vice versa. Accordingly, Baumol (1990) divides entrepreneurship into three types—productive, unproductive, and destructive.

Lucas and Fuller (2017) believes that under certain conditions, Bamoul’s idea can be true. These researchers suggest that social value creation occurs when the best future option for entrepreneurs is known and institutions limit the options.

Discovering and exploiting opportunities and the entrepreneurship development depend on the quality of institutions and not the presence of resources in country. Poor formal and informal institutions in the society will strengthen opportunistic behaviours. The lack of clear rules of the game and the resulting uncertainty will incentivize people to use all opportunities in their benefit in every possible way. In such an institutional space, rent-seeking and corruption (unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship) will prevail over productive activities (productive entrepreneurship). In a poor institutional environment, the transfer of wealth (unproductive entrepreneurship) takes precedence. In most factor-driven countries like MENA countries, there are many economic and natural resources. But institutional quality and structure of governing institutions are so poor that the countries cannot take advantage of the benefits of entrepreneurship.

One of institutional environments affecting the individuals’ incentive structure is the legal environment. Institutions such as property rights, the rule of law, the type of legal system, independence of the judiciary and the courts, contracting procedures, and regulatory burden are important institutions affecting entrepreneurship in such an environment. Then, this section shows that the good quality of these institutions reduces the profitability in activities related to the transfer and destruction of wealth (unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship) and increases it in activities related to the creation of new wealth (productive entrepreneurship).

Entrepreneurs try to discover new opportunities. This is done with the profit motive. This should be done through long-term planning. When entrepreneurs enter entrepreneurial activities, they expect to benefit from the results of their own efforts and not by being expropriate. Also in the event of disputes and quarrels with others, they expect their disputes to be resolved through a strong and righteous legal system. Entrepreneurs in the process of opportunity discovery need spiritual and mental tranquillity (rule of law). They need easy laws and regulations, without any complexity. Easy administrative processes are a business-running requirement. All these indicate that the legal environment can be supportive of entrepreneurs.

In countries with weak and insecure property rights structure, there is no guarantee that benefits of investment and transactions or the results of the entrepreneurial activity are enjoyed by the entrepreneur. In such an environment, there is the possibility of vertical expropriation. So, the entrepreneur is not likely to enter entrepreneurial activities and will spend his time and energy in unproductive activities.

If there is no clear and trustworthy solution to resolve conflicts and disputes of the parties (lack of rule of law), or by weak institutions and widespread impartial corruption, are not resolved objectively (lack of judicial independence and the courts and the inadequate legal system with the structure of society), then the individual is unlikely to engage in entrepreneurial activities. In such an environment, horizontal expropriation will be occur.

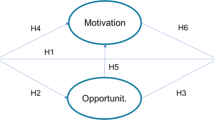

Another important point that prevents the vertical expropriation, facilitates doing business, and accelerates engagement in entrepreneurial activities is the government support of entrepreneurs in the form of regulations such as property rights and reduced regulatory complexity, and in general the regulatory burden. So, it is clear that the strong property rights institution (that prevents the vertical expropriation) and contracts institution (prevention of horizontal expropriation) prevent rent expropriation and enable the entrepreneur to gain profits in the process of discovering opportunities. In such a case, profitability of productive activities (activities related to the creation of new wealth) increases and profitability of unproductive activities (activities related to the transfer and destruction of wealth) reduces. Opportunity entrepreneurship has the greatest influence in this field. Generally, it can be pointed out that (weak and good) institutions affect the level and nature (or types) of entrepreneurship. Weak institutions change the combination of entrepreneurship in favour of unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship, while good institutions change it in favour of productive entrepreneurship. So, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1a

Weak institutional environment has a negative effect on the level of entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 1b

Weak institutional environment has a negative effect on types of entrepreneurship (opportunity and necessity).

2.3.2 The Role of the Entrepreneurs in Institutional Change

In the previous section, it has been explained that institutions are important. If institutions want to perform the explained tasks well, they should have two features—stability and predictability. But the question is whether institutions change and evolve over time. The answer is that they certainly do. Thus, institutions also evolve and are changing. This section shows that entrepreneurs are also important.

Various theories have been proposed for the different institutions and institutional changes (Bjerregaard and Lauring, 2012; Henrekson and Sanandaji, 2011; Yu, 2001; Li et al., 2006; Kuchar, 2015; Henrekson, 2007). These theories can be categorized into six groups:

1. Efficient institutions view or political Coase theorem (PCT).

2. Ideology or the generalized PCT.

3. The incidental institutions view.

4. The social conflict view.

5. Transaction cost theory of institutional change.

6. Entrepreneurial view of institutional change.

According to the theory of efficient institutions (North and the path dependency hypothesis), socially efficient societies select good (economic, etc.) institutions; if there is a need to change, they apply changes in them. In the theory of ideological difference, institutional differences among countries and their ability to change institutions are due to ideological differences among countries. Society leaders decide which institution is good and which is not, and which institutions should be changed. The cause of institutional change from the view of the theory of incidental institutions is attributed to historical events in critical situations.

The political control of a country is held by powerful political groups. So, according to the social conflicts view, economic institutions are selected and changed in a way that maximizes the expected rent of powerful political groups. Usually, institutions that maximize the total surplus of wealth and/or income of the society are not selected. If necessary, institutional changes are applied in favour of these groups.Footnote 9

Mancer Olson, by presenting the theory of collective action, challenges the Coasian ideas to create an institutional change and present a new theory. North and Williamson are also among new institutional economists who seek to explain the causes of an institutional change. North presents the effect of the ideas and the theory of mental patterns and learning process, while Williamson considers this from the perspective of transaction cost economics. Also, discursive theories and discursive institutionalism theories seek to explain the causes of an institutional change. In addition to institutional economics, this topic has also been considered in the Austrian school of economics. Schumpeter is one of the pioneers of the Austrian School. By presenting the concept of novelty, he tries to present the role of entrepreneurs in radical changes. He introduces the entrepreneur as the agent of a change and considers him as equilibrium-disturbing.

Yu (2001) and Henrekson and Sanandaji (2011), with different attitudes, have presented an entrepreneurial theory of an institutional change.Footnote 10 The general view of the theory is that entrepreneurs are institutional change agents. Yu (2001) provides a new theory of the causes of an institutional change by entrepreneurs, by focusing on coordinating the role of human institutions (the theory of Schultz’s human agency), incorporating Schumpeter’s theory of economic responses (adaptive and creative responses) and the theory of entrepreneurial discovery of Kirzner (Kirzner’s entrepreneurship), and utilizing the theory of some Austrian school economists, like Manger and Hayek. He argues that ordinary and extraordinary discoveries of entrepreneurs have different effects. Ordinary discoveries improve production methods and adjust rules (adaptive response), while extraordinary discoveries damage the stability of institutions and thus create uncertainty in the market (creative response). When the stability of the institutions is lost, coordinating economic activities by institutions (one of their main tasks) becomes difficult. Under such conditions, some actions are made in the society. Successful actions in the society are imitated, repeated, and gradually manifested in new institutions. In fact, this institutional change, occurs due to the discovery of entrepreneurs. New institutions created (or modified) again will bear the role of coordinating economic activities of the society.

From the perspective of Li et al. (2006), institutional entrepreneurs are involved in the process of economic activities by resorting to various strategies; in addition to playing the role of Schumpeterian entrepreneurs, they create pro-market institutions. The researchers believe that entrepreneurs—through explicit advocacy of changes in rules and regulations such as lobbying—suggest that their activity is an exception to the existing rules and regulations, and finally facilitate an institutional change (escaping from existing rules and regulations, doing their business, and—if successful—reporting to the government and persuading it to change the laws and rules of the game, i.e. institutions). Thus, they can effectively eliminate institutional obstacles and create better market-oriented institutions.Footnote 11 In fact, Li et al. (2006) and others like Kuchar (2016) and Henrekson and Sanandaji (2011) believe in market-making entrepreneurship. They consider entrepreneurs (through political processes) in accordance with the theory of new institutional economists, as an institutional change agent. This aspect of institutional change has a long history and corresponds to the discussion of political entrepreneurship in political science literature.Footnote 12

Henrekson and Sanandaji (2011) believes that entrepreneurs affect institutions in at least three ways—abiding, evading and altering. The researchers have accordingly presented a new classification of entrepreneurship—abiding entrepreneurship, evading entrepreneurship, and altering entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurs can accept existing institutions and challenge existing institutional basis (abide), evade them (evade), or change and create new institutions with more effectiveness and/or through innovative political activities directly change existing institutions (alter).

In general, entrepreneurs can initiate the process of an institutional change because of confusing rules of the game and inefficient institutions. Also, any institutional change created by entrepreneurs will not necessarily be productive. Because, according to Baumol’s classification of from productive entrepreneurship and unproductive/destructive entrepreneurship, it can be expected that an institutional change created by entrepreneurs is productive or unproductive. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2a

Opportunity-driven entrepreneurs make institutional change.

Hypothesis 2b

Necessity-driven entrepreneurs do not have an effective role in the process of institutional change.

2.3.3 Bidirectional Causality Between Institutions and Entrepreneurship

In Sect. 2.3.1, it is described that institutional arrangements in the economy that affect the profit and motivation of entrepreneurs also determine the level and types (or nature) of entrepreneurship. In other words, there is a causal relationship of (types of) institutions to (types of) entrepreneurs and it is concluded that institutions are important. Also, in Sect. 2.3.2, it is concluded that entrepreneurs can affect existing institutions in many ways, by changing and improving institutions ruling the market and other institutions. Therefore, entrepreneurs are also important in the process of an institutional change and there is a causal relationship of (types of) entrepreneurs to (types of) institutions. Accordingly, there is a feedback relationship and therefore a bidirectional causality between (types of) institutions and (types of) entrepreneurship.

The roots of this bidirectional causality lie in the advocates of public choice school—in particular, the ideas of Buchanan. He believes that the undesirable policies of governments make individuals and entrepreneurs lobby or encourage them to pass laws against the government. This is done through political processes and lobbying. In this environment, entrepreneurs affect existing unfavourable economic and political institutions. Meanwhile, the efforts of individuals and entrepreneurs are affected by the institutional framework and conditions.

In general, it can be concluded that if the quality of institutions is better in the society, productive entrepreneurship is increased. Productive entrepreneurs, by creating new opportunities, provide new conditions for political, policy, and institutional entrepreneurs. These entrepreneurs, depending on the quality of institutions, can strengthen or weaken the institutional quality. If there are institutions with high (low) quality, political entrepreneurs move to productive (unproductive) activities and strengthen (weaken) the quality of existing institutions.

Hypothesis 3

There is a bidirectional causality between opportunity entrepreneurs and institutional quality.

3 Research Methodology

The main purpose of the present chapter is to identify and examine the effect of entrepreneurship factors on MENA member countries. To achieve this purpose, all the factors affecting the level and types of entrepreneurship theoretically were first identified. Given the diversity of institutional factors and their classification variety (Sects. 2.1 and 2.2) the effect of formal (such as property rights) and informal (such as corruption) institutions on the level and types of entrepreneurship (opportunity-driven and necessity-driven) was examined. On the other hand, it was found that entrepreneurs can be the agent of institutional change, so overall five hypotheses were formulated.

To test the research hypotheses, depending on the type of data available (cross-section, time series, panel, spatial, and spatial-panel data), different econometric methods such as path analysis models, structural equations, single equation regression models, system of simultaneous equation model, and causality and co-integration tests can be used.

One of the features of MENA member countries is weak institutional quality and the poor status of entrepreneurship. Apart from systems of simultaneous equation models and causality tests, default by other modelling indicates that the direction of causality relationship is given. In many empirical studies, it is assumed that there is a unidirectional causality from institutions to entrepreneurship. Accordingly, single equation regression models, path analysis, etc. have been used. But based on theoretical section discussions, it is clear that a bidirectional causality is present between entrepreneurship and institutions. Accordingly, in the present chapter panel causality tests have been used.

It is necessary to perform tests of cross-sectional (in-) dependency on the panel to carry out any work in panel data econometrics. Confirming or rejecting the null and alternative hypotheses in these test types (presence or absence of cross-sectional dependence) will determine the type of unit root test and consequently the type of cointegration and causality tests. Also, selection of a test among the tests available depends on available data volume.

In the present chapter, before performing panel causality tests, cross-sectional dependency tests are first performed, based on Breusch–Pagan LM, Pesaran Scale LM, Bias-corrected Scaled LM, and Pesaran CD tests. Then, by panel unit root tests (Levin-Lin-Chu (LLC), Im-Pesaran-shin (IPS), ADF-Fischer, and PP-Fisher), the stationarity of variables is checked. Also, Kao cointegration test and Granger causality test are used.

4 Institutions and Entrepreneurship in MENA Countries

The purpose of this section is to examine the status of entrepreneurship, institutional quality, and the relationship between them in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries. To analyse this relationship, detailed data and information are needed. But one of the limitations in these countries is the lack of sufficient and complete data. In the first part of this section, Entrepreneurial Framework Condition (EFC) data of the entrepreneurial environment in some MENA countries, as reported by Global Entrepreneurship Monitoring (GEM), have been analysed. In the second part, the institutional quality, and in the third part, the relationship between (opportunity-driven and necessity-driven) entrepreneurship and the institutional quality in some MENA countries have been analysed.

4.1 Entrepreneurial Framework Condition (EFC)

EFC data reported by GEM for the period 2008–2015 (including 12 items as described below) have been given to identify the most important factors and major obstacles of the entrepreneurial environment in MENA countries in Fig. 2a–h.

1. entrepreneurial finance

2a. government policies: support and relevance,

2b. government policies: taxes and bureaucracy

government entrepreneurship programmes

4a. entrepreneurship education at school stage

4b. entrepreneurship education at post-school stage,

5. R&D transfer

6. commercial and legal infrastructure

7a. internal market dynamics

7b. internal market burdens or entry regulation

8. physical infrastructure

9. cultural and social norms

In these figures, we can see that the factors internal market dynamics and physical infrastructure have a relatively good status in all years. In 2009 and 2011, in addition to these factors, entrepreneurship education at post-school stage also had a good status. In 2009, commercial and legal infrastructure was also added. But the rest of factors’ status is assessed to be undesired. However, Tunisia in 2009–2012 and Qatar in 2014 had a better status.

Then, Iran’s status is examined in the period 2008–2015. In Iran (Fig. 2i), like other MENA countries, physical infrastructure status is very strong and internal market dynamics are assessed well, but other factors do not have desirable status. Also in 2012, all index statuses were relatively better than other years, while 2011 can be assessed with a relatively not-good status for all 12 indices.

The overall assessment of EFC status in some MENA countries is that there are major obstacles to support entrepreneurship, including educational (entrepreneurship education at school stage and at post school stage), cultural (cultural and social norms), legal (commercial and legal infrastructure), supportive (government policies: support and relevance, government policies: taxes and bureaucracy, and government entrepreneurship programmes), and financial (entrepreneurial finance) obstacles. The countries only have relatively good status in terms of physical infrastructure and the dynamics of internal markets.

4.2 Institutional Quality

In Fig. 3, the status of indices of the institutional quality (property rights as a proxy for formal institutions and control of corruption as a proxy for informal institutions) is given. As can be seen, although the status of property rights is improving in recent years in most MENA countries, it is still undesired (except for UAE and Kuwait). This status can also be seen in the corruption control index. So, it can be concluded that MENA countries do not have a good institutional quality status.

4.3 Causality

To empirically examine the relationship between the quality of institutions and (opportunity-driven and necessity-driven) entrepreneurship, long-term data are needed. Due to the lack of data, causality test has been done between these two variables for factor-driven countries (data available for Angola, Guatemala, Iran, Jamaica, Uganda, and Algeria). The cause for choosing these countries is that Iran and Algeria are among MENA countries. Meanwhile, the characteristics of most MENA countries are almost identical with those of factor-driven countries.

The results of the aforementioned tests in the methodology section indicate cross-sectional independence between variables and countries. Accordingly, the results of the unit root tests show that given variables have a unit root. Cointegration and causality test results are presented in Table 4.

The results presented in Table 4 show that short-run causality only runs from entrepreneurship to institutional quality (IPRI and IPR). This means that (opportunity) entrepreneurs can be a factor for changing the institutional quality in these countries.

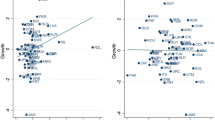

Analysis of the relationship details with indices of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is given in Fig. 4a–c, while indices of necessity-driven entrepreneurship are given in Fig. 4d–f. In Fig. 4a and b, the relationship between opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, international property rights index (4a), and physical property rights index (4b) is positive for Iran and negative for Algeria. But this relationship is still negative for Algeria with intellectual property rights’ index, as shown in Fig. 4c. With necessity-driven entrepreneurship index, this relationship is the inverse of the previous state. For Iran, the relationship is negative, while for Algeria it is positive. In Fig. 5, the relationship is drawn between corruption control index and opportunity and necessity-driven entrepreneurship for Iran and Algeria. The relationship between control of corruption and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship index in Iran is positive and in Algeria is negative. But with necessity-driven entrepreneurship index, the relationship is negative in both countries.

Link between property rights and entrepreneurship in some factor-driven (and MENA) Countries: (2008–2014). (a) Opportunity Entre. and IPRI. 1: Angola, 2: Guatemala, 3: Iran, 4: Jamaica, 5: Uganda, 6: Algeria. (b) Opportunity Entre. and PPR. 1: Angola, 2: Guatemala, 3: Iran, 4: Jamaica, 5: Uganda, 6: Algeria. (c) Opportunity Entre. and IPR. 1: Angola, 2: Guatemala, 3: Iran, 4: Jamaica, 5: Uganda, 6: Algeria. (d) Necessity Entre. and IPRI. 1: Angola, 2: Guatemala, 3: Iran, 4: Jamaica, 5: Uganda, 6: Algeria. (e) Necessity Entre. and PPR in Factor-driven Countries. 1: Angola, 2: Guatemala, 3: Iran, 4: Jamaica, 5: Uganda, 6: Algeria. (f) Necessity Entre. and IPR in Factor-driven Countries. 1: Angola, 2: Guatemala, 3: Iran, 4: Jamaica, 5: Uganda, 6: Algeria

5 Discussion

MENA countries have a great capacity for economic growth (Bakhshi-Dastjerdi and Dallali-Isfahani 2011), but their current development status is very bad (Bhattacharya and Wolde 2010) and a great difference is found in terms of economic and social development between them (Milenkovic et al. 2014; Saha and Ben Ali 2017; Naqvi 2011). These countries have different structures. They can be divided into three categories—countries that are natural resource-rich and importing labour force, countries rich in natural resources and with a labour surplus, and countries poor in terms of natural resources (Saha and Ben Ali 2017). Most of these are developing countries and face many problems, such as high rates of youth unemployment and widespread poverty, especially in natural resource-rich countries. Accordingly, Cho and Honorati (2014) believed that demographic pressure in this area has doubled the need for job creation and entrepreneurship development. On the other hand, the capacity and potential of economic growth of the countries are limited at the moment because of some issues, such as Arab Spring (Saha and Ben Ali 2017), and poor institutional structure (low quality of governance, high level of corruption, the inability of governments to control corruption, property rights not guaranteed, etc.) and entrepreneurship development has become difficult.

EFC data analysis over the period of 2008–2015 for MENA countries showed that only economic environment (internal market dynamics and physical infrastructure) state is appropriate for promoting entrepreneurship. The reason for this can be high population of the countries in the area, demand pressure, and the focus of most governments to provide physical infrastructure. However, the lack of serious governmental support from the entrepreneurs and the problem of firms’ finances (the administrative and financial environment) are serious obstacles faced by entrepreneurs in this area. Microfinance programmes in many countries of this area are inefficient and the banking system does not provide proper support for starting entrepreneurial activities. The risk of entrepreneurial activities in these countries is high because of low quality of institutions, and hence the banking system is reluctant to support them. Also, entrepreneurship education cannot be serious in these countries (because of the weakness of the education system in most countries in the area). Naqvi (2011) also considers entrepreneurship education necessary to improve the entrepreneurial ecosystem function in the countries of the area. Legal and social environments (internal market burdens or entry regulation, commercial and legal infrastructure, and cultural and social norms) are another obstacle to the development of entrepreneurship. The results of Bastian et al. (2015), based on cross-sectional data of entrepreneurial firms in MENA area, also show that national and local governments do not perform their tasks well in terms of creating legal and commercial infrastructure, and are inefficient in this field. Also, in this area, individuals’ views are affected by the values ruling the family and community, which increases the possibility and desirability of the self-employment.

As can be seen in Fig. 3b, during the period of 1995–2016, the status of the control of corruption index in many countries of the region is also below 50 and undesirable. In most of the countries, not only is the state of corruption in recent years inappropriate, but also no effective control is there and the corruption trend is growing. Also, the corruption in MENA is below the median global level, but still quite high (Saha and Ben Ali 2017). According to 2016 information, most people in the area believe that the corruption trend is increasing, governments are not fighting the corruption, and governmental institutions and policy-makers are corrupt and accepting bribes in public services (Pring 2016). In several studies (e.g. Anokhin and Schulze 2009; D’Agostino et al. 2016; Aparicio et al. 2016), it is concluded that corruption had a negative impact on economic growth and entrepreneurship in the countries of MENA as well as in other countries, because the corruption leads to weak foundations of institutional trust, increased investment risk, increased transaction costs, and thus reduced incentive for entrepreneurial activities.

Also, the protection of property rights in the countries of MENA has no good status similar to the corruption control. Except for a few countries, during the period of 1995–2016, property rights index was below 50 in most years and countries. According to the information of MENA countries in the period 1990–2013, Apergis and Payne (2014) examined the effect of institutional quality improvement (such as property rights, judicial independence, and business freedom) in countries with rich natural resources and abundant labour force and countries importing labour force in terms of economic growth and emphasized the importance of institutional quality in these countries.

The analysis of the relationship between the quality of institutions (property rights and control of corruption) and the types of entrepreneurship (opportunity-driven and necessity-driven) in the countries of MENA suggests that the effect of controlling corruption on opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is positive in some countries (such as Iran) and negative in others (such as Algeria), but the relationship with necessity-driven entrepreneurship in the given countries is negative.

The different effects of physical property rights and international property rights index on opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship in these countries is another point. A general presumption in this field cannot be true for the countries of MENA. This is because the programmes supporting property rights and innovation are different among the countries. Also, Bastian et al. (2015) concludes that the incentive of entrepreneurs is strongly correlated with institutional factors in MENA countries.

Another important point about the relationship between institutions and entrepreneurship in MENA countries is that in the short term, a unidirectional causality is found from opportunity-driven entrepreneurship to institutions (property rights). This suggests an important role of opportunity-driven entrepreneurs in changing the economic and institutional structure to improve property rights status and economic growth in MENA countries. The suggestion of using people to fight the corruption as given by Pring (2016), the suggestion to use the private sector in entrepreneurship programmes as given by Cho and Honorati (2014), and the suggestion to consider opportunity-driven entrepreneurs to increase the economic growth and entrepreneurship development as given by Aparicio et al. (2016), are consistent in this regard.

6 Summery and Conclusion

The level and types (or nature) of entrepreneurship among societies and even in a single society are not identical in the same time. Entrepreneurship is found in all societies, races, colours, religions, etc. and it is not a function of resources available in the countries if the speed and intensity of its growth (not its presence or absence) are considered. However, for the question of what factors influence the level and types of entrepreneurship, there is no clear answer. These factors depend on the level of analysis and the nature (or types) of entrepreneurship. The factors affecting the possibility of potential entrepreneurs to become actual entrepreneurs (changes in the levels of entrepreneurship) are different from the factors affecting the choice of various activities by potential entrepreneurs (changes in entrepreneurship). In general, these factors can be categorized into two categories—economic and institutional factors.

The types of entrepreneurship are affected by different environments such as legal, economic, social and cultural, educational, and managerial environments. There is no possibility to explain the effect of all environments and given variables on all types of entrepreneurship at all levels. Therefore, in this chapter, only the effect of the legal environment on entrepreneurship has been theoretically described. The good quality of institutions such as property rights, the rule of law, legal system, independence of the judiciary and the courts, contracting procedures, and regulatory burden (and in general legal environment), reduces profitability of activities related to the transfer and destruction of wealth (unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship) and an increase in activities related to the creation of new wealth (productive entrepreneurship).

The overall assessment of EFC status in some MENA countries shows that there are major obstacles in the path of supporting entrepreneurship, including educational, cultural, legal, supportive, and financial obstacles. These countries only have relatively good status of physical infrastructure and the dynamics of domestic markets. Also, examining the status of indices of the institutional quality (property rights as a formal institutions and control of corruption as an informal institutions) in MENA countries shows that the status of the institutional quality in these countries is weak. Also, the empirical analysis of the relationship between the quality of institutions and (opportunity-driven and necessity-driven) entrepreneurship shows that (opportunity) entrepreneurs can be a factor for changing the institutional quality in these countries.

Notes

- 1.

To further study the differences, see Nelson and Sampat (2001) p. 31ff.

- 2.

To further study this area, see Lin and Nugent (1995).

- 3.

For causes of this forgetfulness, see Ripsas (1998).

- 4.

To read more about these concept and types, see the references listed in Table 2.

- 5.

To read more, see Naudé (2010, p. 87–90).

- 6.

See Greenfield and Strickon (1981).

- 7.

See Bosma et al. (2005).

- 8.

- 9.

To further study the four theories, see Acemoglu et al. (2003).

- 10.

- 11.

Li et al. (2006) believe that facilitating an institutional change is the most attractive practice that can be pursued by an entrepreneur. But it should be noted that the entrepreneur in this case, in addition to market risk, is also facing institutional risk (the risk of failure of institutional change) and thus needs political understanding and skills.

- 12.

Some researchers like Van der Steen and Groenewegen (2009) distinguish between Institutional, Policy, and Political entrepreneurship, but others like Henrekson and Sanandaji (2011) consider them to be the same. Some researchers also like Henrekson and Sanandaji (2011) consider business and market entrepreneurship equivalent to Schumpeterian entrepreneurship, which is different from political entrepreneurship.

References

Acemoglu D (2006) Introduction to economic growth. MIT Press, Cambridge

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson J, Thaicharoen Y (2003) Institutional causes, macroeconomic symptoms: volatility, crises and growth. J Monet Econ 50:49–123

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson J (2005) Institution as the fundamental cause of long-run growth. In: Aghion P, Durlauf S (eds) Handbook of economic growth. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Acs ZJ, Desai S, Hessels J (2008) Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small Bus Econ 31:219–234

Aidis R, Estrin S, Mickiewicz T (2009) Entrepreneurial entry: which institutions matter? IZA Discussion Paper 4123, 2–45

Amoros Espinosa J (2009) Entrepreneurship and Quality of Institutions. United Nations University, World Institute for Development Economics Research, 1–23

Angulo-Guerrero M-J, Perez-Moreno S, Abad-Guerrero I-M (2017) How economic freedom affect opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship in the OECD countries. J Bus Res 73:30–37

Anokhin S, Schulze WS (2009) Entrepreneurship, innovation, and corruption. J Bus Ventur 24:465–476

Aoki M (2007) Endogenizing institutions and institutional changes. J Inst Econ 3(1):1–31

Aparicio S, Urbano D, Audretsch D (2016) Institutional factors, opportunity entrepreneurship and economic growth: panel data evidence. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 102:45–61

Apergis N, Payne JE (2014) The oil curse, institutional quality, and growth in MENA countries: evidence from time-varying cointegration. Energy Econ 46:1–9

Auplat CA, Zucker LG (2014) Institutional entrepreneurship dynamics: evidence from the development of nanotechnologies. Ann Econ Stat, No. 115–116 (Special issue on Knowledge capital in nanotechnology and other high technology industries), 197–220

Azmat A, Samaratunge R (2009) Responsible entrepreneurship in developing countries: understanding the realities and complexities. J Bus Ethics 90(3):437–452

Baez B, Abolafia MY (2002) Bureaucratic entrepreneurship and institutional change: a sense-making approach. J Public Adm Res Theory 12(4):525–552

Baker T, Gedajlovic E, Lubatkin M (2005) A framework for comparing entrepreneurship processes across nations. J Int Bus Stud 36(5):492–504

Bakhshi-Dastjerdi R, Dallali-Isfahani R (2011) Equity and economic growth, a theoretical and empirical study: MENA zone. Econ Model 28:694–700

Bastian B, Zali MR, Mirzaei M (2015) Institutional framework conditions and entrepreneurial attitudes and motivations. In: Nicoló D (ed) Start-ups and start-up ecosystems: theories, models and case studies in the mediterranean area. ASERS Publishing, Craiova, Romania. https://doi.org/10.14505/sse.2015.ch2

Baumol WJ (1990) Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive, and destructive. J Polit Econ 98(5):893–921

Bhattacharya R, Wolde H (2010). Constraints on growth in the MENA region. IMF Working Paper, WP/10/30. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Bjerregaard T, Lauring J (2012) Entrepreneurship as institutional change: strategies of bridging institutional contradictions. Eur Manag Rev 9(1):31–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-4762.2012.01026.x

Bosma N, De Wit G, Carree M (2005) Modelling entrepreneurship: unifying the equilibrium and entry/exit approach. Small Bus Econ 25(1, Special Issue on, Organizational Determinants of Small Business Performance):35–48

Bowen HP, De Clercq D (2008) Institutional context and the allocation of entrepreneurial effort. J Int Bus Stud 39(4):747–767

Brixiova Z, Egert B (2017) Entrepreneurship, institutions and skills in low-income countries. Econ Model 67:381–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2017.02.020.S

Brown C (2005) Is there an Institutional theory of distribution? J Econ Issues 39(4):515–931

Bruton GD, Ahlstrom D, Li H-L (2010) Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Enterp Theory Pract 34(3):421–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x

Busenitz LW, Gómez C, Spencer JW (2000) Country institutional profiles: unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Acad Manag J 43(5):994–1003

Castaño M-S, Mendez MT, Galindo MA (2015) The effect of social, cultural, and economic factors on entrepreneurship. J Bus Res 68(7):1496–1500

Chan S, Clark C, Davis DR (1990) State entrepreneurship, foreign investment, export expansion, and economic growth: Granger causality in Taiwan’s development. J Conflict Resolut 34(1):102–129

Cheah H-B (1990) Schumpeterian and Austrian entrepreneurship: unity within duality. J Bus Ventur 5:341–347

Cho Y, Honorati M (2014) Entrepreneurship programs in developing countries: a meta regression analysis. Labour Econ 28:110–130

Chong A, Zanforlin L (2004) Inward-looking policies, institutions autocrats, and economic growth in Latin American: an empirical exploration. Public Choice 121:335–361

Cuervo A, Ribeiro D, Roig S (2007) Entrepreneurship: concepts, theory and perspective. Springer, Berlin

D’Agostino G, Dunne JP, Pieroni L (2016) Corruption and growth in Africa. Eur J Polit Econ 43:71–88

Dau LA, Cuervo-Cazurra A (2014) To formalize or not to formalize: entrepreneurship and pro-market institutions. J Bus Ventur 29(5):668–686

Djankov S, Miguel E, Qian Y, Roland G, Zhuravskaya E (2005) Who are Russia’s entrepreneurs? J Eur Econ Assoc 3(2/3), Papers and proceedings of the nineteenth annual congress of the European economic association, 587–597

Dopfer K (1991) Toward a theory of economic institutions: synergy and path dependency. J Econ Issues 25(2):535–555

Dutta S (2012) Entrepreneurship & global competitiveness: a study on India. Indian J Ind Rel 47(4):617–633

El Harbi S, Anderson AR (2010) Institutions and the shaping of different forms of entrepreneurship. J Socio-Econ 39(3):436–444

Ellis PD (2011) Social ties and international entrepreneurship: opportunities and constraints affecting firm internationalization. J Int Bus Stud 42(1):99–127

Estrin S, Korosteleva J, Mickiewicz T (2013) Which institutions encourage entrepreneurial growth aspirations? J Bus Ventur 28(4):564–580

Etemad H, Lee Y (2003) The knowledge network of international entrepreneurship: theory and evidence. Small Bus Econ, Special Issue: Internationalizing SMEs 20(1):5–23

Etemad H (2014) The institutional environment and international entrepreneurship interactions. J Int Entrep 12:309–313

Eunni RV (2010) Institutional environments for entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Brazil Vs. Mexico. World J Manag 2(1):1–18

Folta TB, Delmar F, Wennberg K (2010) Hybrid entrepreneurship. Manag Sci 56(2):253–269

Freeman JR (1982) State entrepreneurship and dependent development. Am J Polit Sci 26(1):90–112

Fuentelsaz L, Gonzalez C, Maicas JP, Montero J (2015) How different formal institutions affect opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship. Bus Res Q 18(4):246–258

Greener I (2009) Entrepreneurship and institution-building in the case of childminding. Work Employ Soc 23(2):305–322

Greenfield M, Strickon A (1981) A new paradigm for the study of entrepreneurship and social change. Econ Dev Cult Chang 29(3):467–499

Greenwood R, Suddaby R (2006) Institutional entrepreneurship in mature fields: the big five accounting firms. Acad Manag J 49(1):27–48

Hechavarria DM, Renko M, Matthews CH (2012) The nascent entrepreneurship hub: goals, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and start-up outcomes. Small Bus Econ 39(3):685–701

Henrekson M (2007) Entrepreneurship and institutions. Res Inst Ind Econ (IFN) 707:1–28

Henrekson M, Sanandaji T (2011) The interaction of entrepreneurship and institutions. J Inst Econ 7:47–75

Hitt MA, Ireland RD, Camp SM, Sexton DL (2001) Guest editors’ introduction to the special issue strategic entrepreneurship: entrepreneurial strategies for wealth creation. Strateg Manag J, Special Issue: Strategic Entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial Strategies for Wealth Creation 22(6/7):479–491

Hjerm M (2004) Immigrant entrepreneurship in the Swedish welfare state. Sociology 38(4):739–756

Hodgson GM (2006) What are institutions? J Econ Issues 40(1):1–25

Kalantaridis C, Fletcher D (2012) Entrepreneurship and institutional change: a research agenda. Entrep Reg Dev 24(3–4):199–214

Kent CA, Rushing FW (1999) Coverage of entrepreneurship in principles of economics textbooks: an update. J Econ Educ 30(2):184–188

Kirchheimer DW (1989) Public entrepreneurship and subnational government. Polity 22(1):119–142

Kozul-Wright R, Reyment P (1997) The institutional hiatus in economies in transition and its policy consequences. Camb J Econ 21(5):641–661

Krzyzanowska O (2008) Patterns of self-employment: an empirical comparison of Young People’s Entrepreneurial Pursuits in Poland and Ireland. Polish Sociol Rev 164:417–435

Kuchar P (2015) Entrepreneurship and institutional change: the case of surrogate motherhood. J Evol Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-015-0433-5

Kuchar P (2016) Entrepreneurship and institutional change: the case of surrogate motherhood. J Evol Econ 26(2):349–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-015-0433-5

Levie J, Autio E, Acs Z, Hart M (2014) Global entrepreneurship and institutions: an introduction. Small Bus Econ 42:437–444

Li DD, Feng F, Jiang H (2006) Institutional entrepreneurs. Am Econ Rev 96(2):358–362

Lin JY, Nugent JB (1995) Institution and economic development. Handb Dev Econ 3(38):2301–2370

Lacetera N (2009) Academic entrepreneurship. Manag Decis Econ 30(7):443–464

Lee SH, Peng MW, Barney JB (2007) Bankruptcy law and entrepreneurship development: a real option perspective. Acad Manag Rev 32(1):257–272

Lucas DS, Fuller CS (2017) Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive, and destructive—relative to what? J Bus Ventur Insights 7:45–49

Mair J, Battilana J, Cardenas J (2012) Organizing for society: a typology of social entrepreneuring models. J Bus Ethics 111(3, Social Entrepreneurship in Theory and Practice):353–373

Marinov M, Marinova S (1996) Characteristics and conditions of entrepreneurship in Eastern Europe. J East Eur Manag Stud 1(4):7–24

Marmor TR (1986) Entrepreneurship in Government: an American study. J Publ Policy 6(3):225–253

McDougall PP, Oviatt BM (2000) International entrepreneurship: the intersection of two research paths. Acad Manag J 43(5):902–906

McMullen JS, Plummer LA, Acs ZJ (2007) What is an entrepreneurial opportunity? Small Bus Econ 28:273–283

Meir A, Baskind A (2006) Ethnic business entrepreneurship among urbanizing Bedouin in the Negev, Israel. Nomad People, New Series 10(1):71–100

Milenkovic N, Vukmirovic J, Bulajic M, Radojicic Z (2014) A multivariate approach in measuring socio-economic development of MENA countries. Econ Model 38:604–608

Mitchell DT, Campbell ND (2009) Corruption’s effect on business venturing within the United States. Am J Econ Sociol 68(5):1135–1152

Montgomery AW, Dakin PA, Dacin MT (2012) Collective social entrepreneurship: collaboratively shaping social good. J Bus Ethics 111(3, Social Entrepreneurship in Theory and Practice):375–388

Montiel I, Husted BW (2009) The adoption of voluntary environmental management programs in Mexico: first movers as institutional entrepreneurs. J Bus Ethics 88(Supplement 2: Central America and Mexico: Efforts and Obstacles in Creating Ethical Organizations and an Ethical Economy):349–363

Muralidharan E, Pathak S (2016) Informal institutions and international entrepreneurship. Int Bus Rev 26(2):288–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.07.006

Murphy PJ, Coombes SM (2009) A model of social entrepreneurial discovery. J Bus Ethics 87(3):325–336

Naqvi O (2011) Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: opening the floodgates. Innovations 7(2):11–17

Naudé W (2010) Entrepreneurship in the field of development economics. In: Urban B (ed) Frontiers in entrepreneurship, perspectives in entrepreneurship (Chap. 4). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 85–114

Nelson RR (1984) Incentives for entrepreneurship and supporting institutions. Weltwirtschaftliches Arch 120(4):646–661

Nelson RR, Sampat BN (2001) Making sense of institutions as a factor shaping economic performance. J Econ Behav Organ 44:31–54

Ngunjiri I (2010) Corruption and entrepreneurship in Kenya. J Lang Technol Entrep Africa 2(1):93

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

North DC (2005) Understanding the process of economic change. University Press, Princeton

Nystrom K (2008) The institutions of economic freedom and entrepreneurship: evidence from panel data. Public Choice 136(3–4):269–282

Otahal T (2012) Institutional entrepreneurship: productive or destructive? Available at SSRN 2003747, 1–30

Özcan S, Reichstein T (2009) Transition to entrepreneurship from the public sector: predispositional and contextual effects. Manag Sci 55(4):604–618

Parker SC (2004) The economics of self-employment and entrepreneurship. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pring C (2016) People and corruption: MENA survey 2016. Global Corruption Barometer, www.transparency.org

Rath J, Kloosterman R (2000) Outsiders’ business: a critical review of research on immigrant entrepreneurship. Int Migr Rev 34(3):657–681

Ripsas S (1998) Toward an interdisciplinary theory of entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 10(2):103–115

Rodrik D, Subramanian A, Trebbi F (2004) Institutions rule: the primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. J Econ Growth 9:131–165

Ruttan V, Hayami Y (1984) Toward a theory of induced institutional innovation. J Dev Stud 20(4):203–223

Saha S, Ben Ali MS (2017) Corruption and economic development: new evidence from the middle Eastern and North African countries. Econ Anal Policy 54:83–95

Samadi AH (2008) Property rights and economic growth: an endogenous growth model. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Isfahan University, Isfahan

Sambharya R, Musteen M (2014) Institutional environment and entrepreneurship: an empirical study across countries. J Inst Entrep 12(4):314–330

Sautet F (2005) The role of institutions in entrepreneurship: implications for development policy. Mercatus Center

Schneider M, Teske P (1992) Toward a theory of the political entrepreneur: evidence from local government. Am Polit Sci Rev 86(3):737–747

Schumpeter JA (1934) The theory of economic development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Searle JR (2005) What is an institution? J Inst Econ 1(1):1–22

Shibayama S, Walsh JP, Baba Y (2012) Academic entrepreneurship and exchange of scientific resources: material transfer in life and materials sciences in Japanese universities. Am Sociol Rev 77(5):804–830

Simon-Moya V, Revuelto-Taboada L, Guerrero RF (2013) Institutional and economic drivers of entrepreneurship: an international perspective. J Bus Res 67(5):715–721

Smith E (2012) Explaining public entrepreneurship in local government organizations. State Local Gov Rev 44(3):171–184

Sobel RS (2008) Testing Baumol: institutional quality and the productivity of entrepreneurship. J Bus Ventur 23(6):641–655

Spencer JW, Gómez C (2004) The relationship among national institutional structures, economic factors, and domestic entrepreneurial activity: a multicounty study. J Bus Res 57:1098–11071100

Stenholm P, Acs ZJ, Wuebker R (2013) Exploring country-level institutional arrangements on the rate and type of entrepreneurial activity. J Bus Ventur 28:176–193

Stephen FH, Urbano D, Van Hemmed S (2005) The impact of institutions on entrepreneurial activity. Manag Decis Econ 26(7, Corporate Governance: An International Perspective):413–419

Sud M, VanSandt CV, Baugous AM (2009) Social entrepreneurship: the role of institutions. J Bus Ethics 85(Supplement 1: 14th Annual Vincentian International Conference on Justice for the Poor: A Global Business Ethics):201–216

Szivas E (2001) Entrance into tourism entrepreneurship: a UK case study. Tour Hosp Res 3(2):163–172

Tanimoto K (2008) A conceptual framework of social entrepreneurship and social innovation cluster: a preliminary study, Hitotsubashi. J Commerce Manag 42(1):1–16

Thai MTT, Turkina E (2014) Macro-level determinants of formal entrepreneurship versus informal entrepreneurship. J Bus Ventur 29(4):490–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.005

Thomas AS, Mueller SL (2000) A case for comparative entrepreneurship: assessing the relevance of culture. J Int Bus Stud 31(2):287–301

Troilo M (2011) Legal institutions and high-growth aspiration entrepreneurship. Econ Syst 35(2):158–175

Urbano D, Alvarez C (2014) Institutional dimensions and entrepreneurial activity: an international study. Small Bus Econ 42:703–716

Urbano D, Toledano N, Soriano DR (2010) Analyzing social entrepreneurship from an institutional perspective: evidence from Spain. J Soc Entrep 1(1):54–69

Valdez ME, Richardson J (2013) Institutional determinants of macro-level entrepreneurship. Enterp Theory Pract 37(5):1149–1175

Van der Steen M, Groenewegen J (2009) Policy entrepreneurship: Empirical inquiry into policy agents and institutional structures. J Innov Econ 2(4):41–61

Veciana JM (2007) Entrepreneurship as a scientific research program. In: Cuervo Á, Ribeiro D, Roig S (eds) Entrepreneurship. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 23–71

Veciana JM, Urbano D (2008) The institutional approach to entrepreneurship research. Introduction. Int Entrep Manag J 4(4):365–379

Webb JW, Tihanyi L, Ireland RD, Sirmon DG (2009) You say illegal, i say legitimate: entrepreneurship in the informal economy. Acad Manag Rev 34(3):492–510

Welter F, Smallbone D (2008) Women’s entrepreneurship from an institutional perspective: the case of Uzbekistan. Int Entrep Manag J 4:505–520

Wennekers S, Thurik R (1999) Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Bus Econ 13(1):27–55

Wennekers S, Van Wennekers A, Thurik R, Reynolds P (2005) Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Bus Econ 24(3):293–309

Westland H, Bolton R (2003) Local social capital and entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 21(2):77–113

Williams N, Vorley T (2015) Institutional asymmetry: how formal and informal institutions affect entrepreneurship in Bulgaria. Int Small Bus J 33(8):840–861

Williamson OE (2000) The new institutional economics: taking stock, looking ahead. J Econ Lit 38(3):595–613

Yu YT (2001) An entrepreneurship perspective of institutional change. J Constit Polit Econ 12:217–236

Zahra SA (1996) Governance, ownership, and corporate entrepreneurship: the moderating impact of industry technological opportunities. Acad Manag J 39(6):1713–1735

Zhou M (2004) Revisiting ethnic entrepreneurship: convergences, controversies, and conceptual advancements. Int Migr Rev 38(3: Conceptual and Methodological Developments in the Study of International Migration):1040–1074

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter