Abstract

Seagrass seascapes are 100s m2 to 1000s of km2 coastal regions in nearshore, sandy to muddy benthic environments that are characterized by the presence of seagrasses. Here we explore the development of seagrass seascape research in Australia. Determining the distribution of seagrasses started with mapping their extent, but improvements in remote sensing and statistical modelling has allowed us assess the large scale spatial distribution and temporal dynamics of seagrass seascapes. We use a case study from Moreton Bay, near Brisbane, Queensland to demonstrate changes in seagrass meadows over time. Terrestrial landscape indices and their use in seagrass studies is reviewed. Some indices perform better to summarize patch to meadow scale changes in the distribution and structure of seagrasses. A case-study is then presented, comparing landscape indices calculated from observed changes in seagrass patches and meadows to a spatially-explicit model simulation, to explore the drivers for changes in the seagrass seascape’s demographic processes, clonal growth and recruitment from seeds. The role of landscape structure in the movement and abundance of associated fauna in seagrass seascapes using landscape approaches is then reviewed. This is followed by a summary outlining directions for future research that combine landscape ecology and remote sensing techniques with population and community biology.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

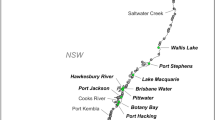

Seascape ecology is the application of landscape ecology to the marine environment, and is based on concepts and techniques developed for terrestrial systems (Robbins and Bell 1994). It is an area of study that broadly looks at spatial variation in landscapes across a range of habitat elements and space and time scales. A landscape is larger than an individual’s immediately observable area and landscape studies typically address heterogeneity across landscape elements at very large spatial scales relative to the organism or process of interest (Bell et al. 2006). Landscape ecology includes understanding patterns and interactions among ecosystems within a defined area, and the way these patterns and interactions affect ecological processes. Of particular interest is the unique effects of spatial heterogeneity on biotic interactions. Spatial dynamics, or patch dynamics in marine systems has been extensively studied for many decades (e.g. Hutchinson 1953; Steele 1978; Pickett and White 1985; Levin and Paine 1974) and these studies have been a major influence in the theoretical development of terrestrial landscape ecology. More recently since the seminal paper of Robbins and Bell (1994) the explicit examination of spatial arrangement, patchiness, edge effects, movement and connectivity across landscape elements, been applied to the study of seagrasses in the marine environment, where it is now commonly referred to as seascape ecology. Our intentions for this chapter are to summarize seagrass seascape studies in Australia by describing pattern through mapping, characterizing the landscape features through indices, modelling seagrass growth across landscapes and by summarizing the association and movement of mobile fauna in seagrass seascapes (Fig. 9.1).

Understanding the spatial relationships between seagrass species and their environment at a seascape scale is required to effectively manage seagrass ecosystems under increased anthropogenic pressures (Orth et al. 2006a; Kilminster et al. 2015). The issues of scaling processes that determine the survival and growth of seagrasses and associated biota to the dynamics of seagrasses in shallow nearshore coastal and estuarine environments are only just being treated systematically by marine researchers (e.g. Kendrick et al. 2008), yet large gaps remain in our knowledge of seagrass seascapes, limiting our ability to predict trends for sustainable management and conservation. This Chapter will address our present knowledge of seagrass seascapes, focusing on scales of influence both in time and space, describing seascape dynamics, determining scaling of physical and biological drivers of seascape pattern, and drivers of the movement and abundance of seagrass associated biota through seagrass seascapes.

Most studies on seagrass spatial dynamics have been conducted on relatively small scales, many focus on describing the growth rates of seagrass rhizomes measured exclusively at the scale of shoots (e.g. Brouns 1987; Williams 1990; Olesen and Sand-Jensen 1994). These results have been scaled upwards directly to the functioning of the patch and meadow (Kendrick et al. 1999, 2005a; Sintes et al. 2005; Renton et al. 2011), but there is growing evidence that seagrass seascapes are not solely driven by shoot scale interactions and scaling shoot dynamics to the seascape only accounts for a small proportion of the broad scale dynamics in seagrass meadows (e.g. Kendrick et al. 2008).

Seagrass mapping of historical changes in seagrass distributions (Kendrick et al. 1999, 2000, 2002; Roelfsema et al. 2014) have demonstrated that the rate of colonization exhibited by some seagrasses is too fast for vegetative spread from the edge of existing meadows and is more likely a multi-stage process of short distance dispersal, patch establishment, patch expansion and coalescence, all working below the grain or resolution of imagery used in mapping. The relationship between broad-scale decadal changes in seagrass distributions and plant-related processes proposed as the drivers (colonization, growth, and competition between seagrass species at the shoot and meadow scale) has yet to be satisfactorily resolved (Kendrick et al. 2005a, 2008), since only a few of these mapping exercises attempted to correlate the spatial changes in seagrass landscapes to underlying processes generating that change (Fonseca and Bell 1998; Robbins and Bell 2000; Fredericksen et al. 2004a).

It is difficult to infer process from pattern (Wagner and Fortin 2005; van Teeffelen and Ovaskainen 2007) and, unlike most terrestrial systems, the missing link between pattern and process is pattern at broader scales (Kendrick et al. 2008; Ooi et al. 2014). Seagrass landscapes, even when composed of large and slow-growing seagrasses, can be highly dynamic over time scales of decades (e.g. Larkum and West 1990; Quammen and Onuf 1993; Short and Burdick 1996; Kendrick et al. 2000, 2002; Seddon et al. 2000; Fredericksen et al. 2004b), contrary to the general statement for most of the temperate Australian seagrasses, thought to be unable to colonize at measurable rates and once disturbed rarely recover (Clarke and Kirkman 1989; Kirkman 1985).

Habitat fragmentation is increasingly common in both terrestrial landscapes and marine seascapes. The subtidal temperate regions of southern Australia support extensive seagrass seascapes that are characterized by mosaics of multi-species seagrass patches and meadows that are interspersed in sand (Walker et al. 2001; Carruthers et al. 2007). Long-term mapping studies have indicated that these seagrass seascapes exhibit spatial changes in seagrass cover and distribution (Kendrick et al. 2000, 2002) that can be defined along a continuum from many small seagrass patches interspersed in sand, to a single continuous seagrass meadow. The process of fragmentation has been described by a range of ecological, physical and anthropogenic processes, including the influence of different species of seagrass an their specific life history traits, growth and recruitment rates (Carruthers et al. 2007; Hastings et al. 2007; Kendrick et al. 2008).

Different seagrass assemblages possess unique sets of physiological and morphological characteristics, that provide them with the mechanisms necessary for persistence in particular environments and may also influence differences in the spatial organization of seagrass assemblages. As clonal organisms, seagrasses are capable of reproducing without sexual interactions. Lateral expansion and architecture of seagrass relies heavily on elongation of rhizomes (i.e. the rate of addition and size of rhizome internodes), branching pattern (i.e. the branching frequency and branching angle), and length of the rhizomes between consecutive shoots (Marba and Duarte 1998; Kendrick et al. 2005b; Sintes et al. 2005; Renton et al. 2011). Seagrass are also capable of reproducing through sexual means but, as with other clonal plant populations, seedling establishment appears to be infrequent (Inglis 2000a; Kirkman 1998 but also see Kendrick et al. 2012, 2017). The reproductive characteristics (i.e. the number of seeds released per year), dispersal and recruitment of reproductive and vegetative propagules can influence the spatial pattern of seagrass assemblages (Inglis 2000b; Hovey et al. 2015; Kendrick et al. 2012, 2017; McMahon et al. 2014), yet it is uncertain about the magnitude of the role seagrass recruitment plays in the spatial structuring of seagrass seascapes.

Mapping of seagrasses in Australia started in the 1970s but improvements in remote sensing and statistical modelling of species distributions has led to great advances in our detection of seagrasses and our understanding of the large scale spatial distribution and spatial dynamics of seagrass seascapes. We demonstrate the capacity of modern remote sensing to assess change in seagrass seascapes over time through a case study from Moreton Bay, near Brisbane, Queensland (also see the remote sensing chapter). In the 1990s and through the 2000s landscape indices were increasingly used to describe the structure and fragmentation of seagrass meadows (Fig. 9.1). Landscape indices are introduced with specific focus on their use in seagrass studies. They are also utilized in the landscape modelling case study that follows the indices section. Modelling was first used in seagrass research in the 1990s and early 2000s to assess the contributions of demographic processes (clonal growth and recruitment from seed) on emergence of pattern across seagrass seascapes. A case study is presented as a demonstration of the use of landscape modelling to demonstrate potential contributions of clonal growth and seed recruitment to observed changes to seagrass seascapes on Success and Parmelia Banks , near Perth Western Australia. Finally, we summarize a large body of Australian and international literature on the role of landscape structure in the movement and abundance of associated fauna in seagrass seascapes using landscape approaches . This is followed by a summary outlining directions for future research.

2 Mapping Change in Seagrass Seascapes

The development of seabed-mapping technologies in the last two decades (Kenny et al. 2003) has enabled the generation of accurate maps of landscape classes within coastal seascapes, like seagrass meadows , reefs and un-vegetated sand. These seabed mapping methods are useful for assessing the state of living resources, similar to that which occurs for terrestrial resources, and are increasingly in demand for a variety of applications, including: marine park placement and zoning (Friedlander et al. 2003); marine resource management (Bax et al. 1999); environmental monitoring (Kendrick et al. 2000, 2002); holistic catchment management; and integrative ecological research (Durako et al. 2002; Fonseca et al. 2002). Mapping the extent of seagrass seascapes has traditionally served as a general indicator of coastal ecosystem health (Kilminster et al. 2015) and more recently has served the analysis of spatial patterns using landscape metrics. However, an understanding of the spatial heterogeneity within meadow dynamics such as composition, density and productivity (biomass) is also important.

In the last two decades, effort has focused on developing efficient marine survey equipment and data acquisition systems to map a wide range of abiotic and biotic features on the seafloor (Kenny et al. 2003; McRea Jr. et al. 1999; Solan et al. 2003; Chap. 15). This has been augmented by the application of sophisticated statistical modeling methods to benthic datasets (e.g. multivariate analysis: Freitas et al. 2003; CARTS: Holmes et al. 2008; Hovey et al. 2012; generalized additive models: Garza-Perez et al. 2004; geostatistics: Kendrick et al. 2008; Ooi et al. 2014). However, as seagrasses are commonly found in shallow clear water, an appropriate approach to mapping seagrass extent involves using remotely sensed image data such as airborne or satellite multispectral or hyperspectral imagery.

More recently, composition and structure of seagrass meadows have been mapped as a direct function of remotely sensed image data. Historical maps of seagrass seascapes that provide composition and structure information were typically visually estimated (Young and Kirkman 1975; Hyland et al. 1989). Time series of seagrass structure may be derived from some historical aerial image data, but it was not until the 1980s that moderate spatial resolution (5–30 m pixel size ) satellite image data (e.g. Landsat satellites) were available to create true time series of seagrass structure using directly comparable images which allows quantitative assessment over time (e.g. Lyons et al. 2013) (Fig. 9.2). In the 2000s, high spatial resolution (1–5 m pixel size) satellite image data (e.g. IKONOS, Quickbird, Worldview) became available to create time series that allows quantitative assessment of seagrass composition (e.g. Fig. 9.3, Roelfsema et al. 2014), although some rare exceptions exist for moderate resolution data (Dekker et al. 2005).

Annual (lower panel) versus monthly (upper panel) monitoring of the area covered by three classes of seagrass percentage cover, high (100–60%), moderate (60–40%) and low (40–0%) for Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia (Lyons et al. 2013)

Annual mapping of seagrass species (composition) for Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia (Roelfsema et al. 2014)

Examples of seagrass biomass mapping for one or two image dates have been common since the 1990s (Phinn et al. 2008), but time series that allow quantitative assessment of the spatial distribution and absolute weights of above ground biomass (Fig. 9.4) have only recently been demonstrated (Roelfsema et al. 2014; Lyons et al. 2015). These methods have been driven by the increased interest in inventory and dynamics of coastal Blue Carbon (the carbon sequestered by seagrass, mangrove and saltmarsh ecosystems), and globally and publicly available satellite image data archives.

Annual time-series of above ground biomass for Moreton Bay, Queensland , Australia (Lyons et al. 2015)

3 Seagrass Landscape Indices

Metrics and indices that quantify ecologically important spatial patterns are necessary for linking spatial patterns to ecological processes (Turner 1989). Real landscapes contain complex spatial patterns in the distribution of resources that vary over time; so the ability to quantifying these patterns and their dynamics is the core of landscape pattern analysis. Once an area of interest has been mapped, the seascapes are often represented visually using several different conceptual models with varying cartographic properties (i.e. spatial and thematic resolution; Wedding et al. 2011). A common representation of seascape structure is the ‘patch-matrix’ model, where the map classification is binary with focal ‘high quality’ patches embedded in a matrix of ‘lower quality’ habitat and is based conceptually upon island biogeography theory (Wedding et al. 2011). The focus of this patch-matrix model has been on patch attributes such as area (i.e. species–area relationships), biotic response to patch edges, perimeter: area ratios, patch shape, and inter-patch distances and/or isolation. From these attributes the quantifiable metric or indices used to characterize the spatial structure of seascapes were developed, stemming from the original need to quantify the complex spatial heterogeneity represented in remotely sensed images (both aerial photography and satellite imagery).

No individual index can capture the full complexity of spatial patterns, and in most cases multiple indices are required for analysing landscape configuration (Saura 2002). A set of metrics are often considered useful when they are selected for a particular objective, measured values are well-distributed over a range of scales and metrics are relatively independent. These concepts and analytical techniques in landscape ecology are well developed in terrestrial systems and provide a framework that can be readily applied to assess broad-scale seagrass patterns and disturbances (Wedding et al. 2011).

Landscape indices have been shown to be a useful tool for characterizing marine benthic communities (Garrabou et al. 1998). In most seagrass seascape studies, spatial properties relating to fragmentation or animal-habitat associations have been described with simple measures like average patch size and the numbers of seagrass patches per unit of area (Bell and Hicks 1991; Irlandi 1994; Irlandi et al. 1995; Pittman et al. 2004). More complex indices have occasionally been used such as Connectivity, Patch Dispersion (cumulative variation of Nearest Neighbour Distance), Patch Adjacency (Interspersion and Juxtaposition) and Contagion to measure various spatial attributes of seagrass seascapes (Robbins and Bell 2000; Hovel and Lipcius 2001; Santos et al 2015).

The requirements of choosing indices in fragmented landscapes were explicitly stated by Jaeger (2000). He suggested that the selection of indices should be based on: (i) the extent to which they measure fragmentation; (ii) mathematical homogeneity with increasing extent; (iii) intuitive interpretation; (iv) detection of important structural features of fragmentation; (v) comparison of regions of different grain and extent ; (vi) mathematical simplicity; (vii) modest data requirements; (viii) low sensitivity to small patches; and (ix) monotonous reaction to different fragmentation phases. In 2005 Sleeman et al. reviewed the literature relating to the implementation and testing of indices specifically for the analysis of fragmented seagrass landscapes , identifying a total of 24 indices (Gustafson and Parker 1992; Riiters et al. 1995; Haines-Young and Chopping 1996; Reed et al. 1996; Schumaker 1996; Jorge and Garcia 1997; Li and Archer 1997; Gustafson 1998; Hargis et al. 1998; Kendrick et al. 1999; O’Neill et al. 1999; D’Eon and Glen 2000; Jaeger 2000; Robbins and Bell 2000; Hovel and Lipcius 2001). These 24 indices were reduced to 11; grouped according to the principle aspects of spatial pattern they measure as defined by McGarigal (2002): Area/density/edge, Shape, Dispersion, Subdivision and Connectivity.

Within these groups, individual indices were examined against the following eight criteria:

-

(1)

Can be defined at a class-level (e.g. seagrass or sand in a shallow subtidal landscape);

-

(2)

Specifically relate to fragmentation;

-

(3)

Are relatively insensitive to scaling issues such as grain and extent ;

-

(4)

Have low correlation with other indices;

-

(5)

Relate to ecological processes;

-

(6)

Are sensitive to important structural properties;

-

(7)

Are applicable for comparing landscapes of different areas; and

-

(8)

Can be calculated in a raster data format.

Sleeman et al.’s (2005) analysis concluded that no single index can be used to comprehensively quantifying the complex spatial aspects of fragmentation and that multiple indices should be used which are not strongly correlated and are easily interpretable. Based on the overall performance of indices and index compatibility, Area Weighted Mean Perimeter to Area Ratio , and Landscape Division, were found to be preferred indices for providing a comprehensive assessment of spatial structure while avoiding strong correlation among indices.

Area Weighted Mean Perimeter to Area Ratio generally measures the complexity of patch shapes in terms of whether they are simple and compact or irregular and convoluted, with a perfect square patch having a value of 0.01, and specifically looks at the overall perimeter and area of a class rather than individual patches (McGarigal and Marks 1995). Landscape Division is the area weighted mean of area and is given as a probability that two randomly chosen pixels in a landscape are not situated in the same patch (Jaeger 2000). LD = 0 when the landscape consists of a single patch and increases to one as patches become more maximally subdivided, (when every cell is a separate patch). The Landscape Division index is probably the most useful on its own as it can discriminate between a greater range of habitat patchiness in the landscape. These recommendations by Sleeman et al. (2005) have been used recently to document seagrass loss and fragmentation from a dataset spanning 71 years in Florida (USA), providing evidence that coastal developments have transformative impacts on vegetated habitats, with undetermined consequences for the provisioning of ecosystem goods and services (Santos et al. 2015).

4 Modelling Seagrass Seascape Processes

Spatially-explicit modelling is a very useful approach for investigating how interactions between organisms and their environment influences distribution of seascape classes, like seagrass patches and meadows . Such models can be used to describe processes as simple as linear relations between a couple of variables or as complex as projecting the interaction between different organisms and their environment over time (Pastor 2011). Despite the variety of modelling techniques currently available, all aim to simulate a process and its responses based on maximum simplicity, thus restricting the variables to only the ones that, are of interest or that produce greater effect while obtaining meaningful and realistic results. It is therefore imperative for any kind of modelling exercise to describe the capabilities and limitations of the simulations undertaken as well as their real use or application. The models can then add complexity depending on the number of variables as the input and the relations among these variables. The increase in computer power has allowed us to expand and assess more complex interactions, increasing the number of factors in the system while reducing the solving time.

Seagrass seascapes inhabit certain environments over a determined area, where the current environmental conditions are often used in models to define the suitable habitat or the fundamental niche. If biological factors such as competition are included in models, then the model represents the realised niche of an organism. The geographical expression of its realised niche at a particular time is the potential distribution of a species, denoting areas where there is fulfilment of both abiotic and biotic requirements (Soberón and Peterson 2005). Modelling suitable habitat for seagrasses aids in understanding contemporary seascape patterns, particularly in determining if gaps are edaphic in nature or a result of disturbance driven mortality (Bell et al. 1999). Understanding the evolution of seascapes however, depends on numerous factors affecting the system at different timescales. . Shifts can result from geological processes (millennia), cyclical events (decadal), rapid events (days) and lastly to biological responses within the organisms (minutes to seconds). It is therefore important to consider the timescale in question to properly address the processes influencing the dynamics of seagrass seascapes and the spatial extent and frequency at which responses are measurable or relevant (Zhang et al. 2013). Some of the major limitations on spatial modelling are the heterogeneity of the environment and our inability to work with the inherent complexity. Instead, we tend group all the spatial information into units that average information into a homogenous cell. The resolution of that spatial unit is a key factor when trying to explain specific processes. To properly address the dynamics of the environment to model, we need to determine the correct resolution and time-scale in order to work with the best amount of data with real implications for the time scale in question.

Spatially–explicit, individual-, or agent-based models , have been developed for research into seagrasses and the utilization of seagrass seascapes by mobile marine animals. These models simulate populations and communities by following individuals and their properties through space and time, taking into account attributes such as spatial location and physiological traits, behaviours and interactions among individuals (DeAngelis and Grimm 2014). As these models can incorporate any number of individual level mechanisms, they vary in their complexity and their purpose. For example, agent-based modelling and has been employed to assess fairy rings in sedges; a process of central dieback with regeneration within patches, and a structure recently observed in seagrasses (Wong et al. 2011). Agent-based models were also used to demonstrate that similar rates of horizontal and vertical rhizome growth in Posidonia oceanica was a source of the vertical structure in meadows in the Mediterranean, creating biotic reefs 1–3 m above the sediment (SWARM: Kendrick et al. 2005a). Spatial and temporal movement of drifting macro-algae was modelled to assess their influence on re-establishment of eelgrass in a Danish Fjord using an agent-based modelling framework (MIKE 3 FM ECOlab: Canal-Vergés et al. 2014). An individual-based model was used to explore the effect of seagrass fragmentation on the predator-prey relations of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus (NETLOGO: Hovel and Regan 2008). Below, as an example of the value of landscape modelling , we describe in detail the application of an agent-based model that tests the nested hypotheses that clonal growth alone or clonal growth with recruitment from seeds could account for decadal changes in spatial arrangement in seagrass seascapes.

4.1 Case Study: Influence of Clonal Growth and Sexual Recruitment on Landscape Structure of Seagrass Assemblages

Seagrass ecosystems occur over broad spatial scales (seascapes) where they are characterised by a continuum from fragmented patches to continuous meadows. Seagrasses within these seascapes can contain one or multiple species of seagrasses with different rates of clonal growth and sexual recruitment . This study models the roles of clonal growth and sexual recruitment of Posidonia spp. and Amphibolis griffithii in accounting for changes in landscape fragmentation over decades.

Interactions between seagrass life-history processes and landscape patterns are complex, occur over large spatial and temporal scales and are difficult to explore through empirical experiments. Models of clonal growth (i.e. rhizome extension rates and branching angles) of different seagrass species have indicated that they influence spatial arrangement of seagrass patches (Marba and Duarte 1998; Sintes et al. 2005; Renton et al. 2011) and differences in clonal growth between seagrass species have been scaled-up to explain spatial patterns of seagrasses at seascape-levels (Vidondo et al. 1997; Bell et al. 1999; Kendrick et al. 1999, 2005a, b). Linking clonal growth and sexual recruitment to seascape-level patterns may be possible through the use of agent-based modelling techniques. In this study, we utilize the application of a spatially explicit , agent-based model , specifically developed to simulate clonal growth and sexual reproduction of seagrasses and other marine clonal organisms (seagrasses: Kendrick et al. 2005b; corals: Sleeman et al. 2005).

4.2 Methods

4.2.1 Study Region and Seagrass Assemblages

Maps of historical seagrass cover derived from geo-referenced aerial photography captured at a scale of 1:25,000 in 1972 and 1999 from the Success and Parmelia Bank regions, of Western Australia (32° 02′S, 115° 42′E: Fig. 9.5a and classified to species from towed video (see Kendrick et al. 2000 for methods). The 1972 and 1999 maps of seagrass distributions were saved as raster images with a 2 × 2 m-pixel resolution (Fig. 9.5b). Two seagrass genera, Posidonia spp. and Amphibolis grifithii, covered much of the study area (Kendrick et al. 2000, 2008; Holmes et al. 2007) and were the focus for this modelling exercise (Fig. 9.5a).

a On top, the study area in the South-west of Australia with the seagrass cover of 1972. b An example of a spactial unit consisting of 12.96 ha. c the grid of that spatial unit into cells of 4 m2 and the assemblage Kernel of growth for the model, where the bold numbers in parenthesis represent the directional prioritation based on the study by Cambridge et al. (2002)

4.2.2 Analysing Changes in Fragmentation of Seagrass Assemblages Between 1972 and 1999

The 1972 and 1999 distribution maps for Posidonia spp. and Amphibolis grifithii were divided into 12.96-ha square regions (landscape units) (Fig. 9.5b). The resolution (grain) and size (extent) of the landscape units was representative of the size distribution of seagrass patches within the entire study area, where grain and extent were 2–5 times smaller and 2–5 times larger than the smallest and largest patch sizes, respectively (O’Neill et al. 1999). Only 12.96 ha units that exclusively contained either Posidonia spp. or Amphibolis grifithii in both 1972 and 1999 were extracted and used in the analysis.

4.2.3 Modelling Clonal Growth and Clonal Growth with Sexual Recruitment of Seagrass Assemblages

Swarm is a spatially explicit , agent-based simulation model that was developed by researchers at the Santa Fe Institute as a tool to investigate spatial behaviour of interactive biological systems (Kreft et al. 1998; Luna and Stefannson 2000; Villa and Costanza 2000). In this study, Swarm was customized to specifically simulate clonal growth and sexual recruitment of seagrasses and details of the model can be found in Kendrick et al. (2005b). The seagrass model used in this study relies on the following assumptions: environmental conditions, such as nutrient availability, light and wave energy are considered to be uniform across the extent of the modelled space, and; the model is spatially unrestricted (modelled as a torus) such that boundaries do not inhibit growth.

The model adopts an agent-based approach whereby seagrasses are represented as a collection of units or agents within a grid (the species world), which interact via discrete events. The characteristics and behaviour of agents are defined by the implementation and interaction between three input files: (i) the assemblage kernel file, that determines the directional neighbourhood of clonal growth ; (ii) the assemblage parameter file, that contains specific parameters including rhizome growth rate, life-span and sexual recruitment from the literature (Chap. 8), and; (iii) the initial map (specifying the starting location of the seagrass agents (180 × 180 cells ≅ 2 m2 pixels) Fig. 9.5b, c).

Patch growth data of Posidonia australis seagrass patches from Oyster Harbour (Cambridge et al. 2002), near Albany in Western Australia was utilised as a conservative standard from which the directional growth (kernel files) of both Amphibolis griffithii and Posidonia spp. were defined. The average annual patch expansion in the eight cardinal directions was calculated from patch growth data and plotted in a compass rose diagram (Fig. 9.6c).

Rhizome growth rate in the model (growth probability factors) was the only parameter that was varied between the two genera and all other parameters were kept constant between both species. The growth probability factors for Amphibolis griffithii and Posidonia spp. were 0.22 and 0.11 or approximately 18 and 9 cm of radial growth per year, respectively.

The same parameter values for recruitment from seeds (seed probabilities, seedling survival, seedling interval, maximimum and minimum number of seeds per agent, and maximum number of seedlings allowed in the landscape) and minimum and maximum life span were used for both Amphibolis griffithii and Posidonia spp. There is little published information available for sexual recruitment of Amphibolis griffithii and Posidonia spp. (but see Rivers et al. 2011; Kendrick et al. 2017). Since seagrass seedlings occupy considerably smaller areas than 2 × 2 m patches (the minimum cell size), the seed interval was extended from once a year to once every 4 years, as it would take at least that amount of time before a cell could be partly occupied by a seedling growing between 6.5 and 19 cm per year. In addition to extending the seedling interval, the seed minimum and seed maximum values of individual agents was adjusted so that a single 2 × 2 m patch was only capable of producing either a single recruit (2 × 2 m patch) or no recruits. To ensure that recruitment did occur annually, the seed probabilities for the two assemblages were set at 0.9. The maximum number of seedlings allowed within the landscape at any one time step was set at 5,000 recruits or 6.5% of the total area (180 × 180 = 32,400 grid cells). Seedling survival for the first year was set as 1 in 10 (10%) to correspond with the high rates of recruitment mortality observed in the field (Kirkman 1998) although from unpublished recent studies this may be high. Posidonia australis had a recorded rhizome lifespan (ranging between 8 and 18 years) this was applied as the minimum and maximum life-spans for both Amphibolis griffithii and Posidonia spp (Marba and Walker 1999) within the model.

Twenty landscape units from 1972 were selected randomly as the initial maps for each species. Clonal growth , with and without sexual recruitment, were modelled for each landscape unit for the 27 year period (1972–1999).

Following the completion of the modelling, the output maps were exported into a GIS and ran through the landscape indices software Fragstats 3.3 (McGarigal and Marks 1995) to calculate Area Weighted Mean Perimeter to Area Ratio , Landscape Division and total seagrass area , median patch area and number of patches. One-tailed paired t-tests were carried out to compare the differences between landscape structure among modelled outputs after 27 years (1972–1999) and measured structure from aerial photographs in 1999.

4.3 Results

4.3.1 Comparing Model Outputs to Actual Seagrass Landscapes in 1999

Modelled reduction in fragmentation of Amphibolis griffithii and Posidonia spp. between 1972 and 1999 could be explained by clonal growth processes in the absence of sexual recruitment . Fragmentation for both modelled seagrass assemblages, measured as Landscape Division, was statistically significantly less than that observed in 1999 (Table 9.1 and Fig. 9.6).

4.3.2 Amphibolis griffithii

Modelling clonal growth alone produced similar spatial distributions to the actual observed spatial distributions of Amphibolis griffithii in 1999. Total seagrass area, median patch sizes , number of patches and seagrass fragmentation were not significantly different when comparing clonal growth from the model to the observed 1999 coverage (Table 9.1). The outputs produced from simulating 27 years of clonal growth and sexual recruitment for Amphibolis griffithii, had statistically significant less fragmentation (LD index) compared to observed distributions in 1999 (Table 9.1). Similar total seagrass areas , numbers of patches, median patch sizes, patch perimeter to area ratios (AWMPAR values) were observed between the model and 1999 aerial photographs.

4.3.3 Posidonia spp.

The spatial distribution (i.e. total seagrass area , median patch size, number of patches and fragmentation) produced by simulating clonal growth of Posidonia spp. was not significantly different from measured Posidonia landscapes in 1999 (Table 9.1). When clonal growth was combined with sexual recruitment , modelled landscape units had significantly greater total seagrass area and significantly lower Landscape Division (fragmentation) than observed from aerial photographs in 1999 (Table 9.1 and Fig. 9.6).

4.4 Discussion

The most parsimonious interpretation from modelling is that clonal growth of seagrass patches and meadows existing in 1972 were responsible for the observed decrease in seagrass fragmentation and increase in seagrass cover between 1972 and 1999. Similarly, clonal growth was found to be the main mechanism for recolonisation and gap closure of seagrass meadows for Cymodocea nodosa, Enhalus acoroides, Halodule wrightii, Syringodium filiforme, Thallassia hemprichii, Thallassia testudinum and Zostera caprocornii (Duarte and Sand-Jensen 1990, Williams 1990, Duarte et al. 1997, Rasheed 1999, Rollon et al. 1998, Almela et al. 2008). Infilling and coalescence of seagrass patches increased when we included sexual recruitment in the agent-based model.

Faster rates of meadow cohesion in modelled Amphibolis griffithii was solely driven by faster rhizome spreading rates, as this was the only parameter we varied between taxa in the agent-based model. Horizontal rhizome growth rates of Amphibolis griffithii are 2–5 times faster (22.6 cm year-1: Marba and Duarte 1998, Marba and Walker 1999) than the Posidonia spp. (4–9.3 cm year−1: Marba and Duarte 1998, Marba and Walker 1999).

Studies on Posidonia australis , P. coriacea, P. sinuosa, and Amphibolis griffithi have speculated that sexual reproduction has some importance in the recovery and maintenance of meadows, yet few studies have endeavoured to quantify this relative influence (Cambridge et al. 2002; Campey et al. 2002, 1999, 2000, 2012; Marba and Walker 1999) Posidonia coriacea contributes as little as 15 ± 3 seeds m−2 year−1 on Success Bank (Campey et al. 2002). Even if reproductive propagation appears to be occurring, seedling mortality is high, due to processes such as predation (Orth et al. 2006b and loss associated with storms and wave action (Kirkman 1998). Genetic studies of Amphibolis species in Western Australia suggest that sexual reproduction may be of limited importance to the maintenance of populations since they comprise few or single genotypes (Waycott et al. 1996).

In this modelling exercise we have not incorporated stochastic disturbance , and clonal growth and sexual recruitment are explored where disturbance through biological and physical mechanisms is a small-scale spatially random process expressed as mortality of the agents in the model (an agent is a 2 m × 2 m patch of seagrass). Persistent hydrodynamic disturbances such as wave forcing are known to affect patch and meadow configuration; examples for temperate Australia include linear bed forms in Posidonia spp. in Cockburn and Warnbro Sound and Rottnest Island , Western Australia (Marba and Duarte 1995; Cambridge 1999; Smith and Walker 2002; Kendrick et al. 2000). The influence of physical processes on the spatial configuration of seagrass landscapes has been considered in recent seascape modelling (Suykerbuyk et al. 2016) and is a valuable area of future research.

4.5 Conclusion

In conclusion, agent-based modelling is a heuristic tool for developing hypotheses to test the links between seascape pattern and biological processes. In this case study the outputs from an agent-based model indicated that clonal growth alone appears to explain the increases in seagrass area (Kendrick et al. 2000) and cohesion of seagrass patches and meadows observed on Success and Parmelia Banks between 1972 and 1999. Also, increases in seagrass area and decreases in fragmentation of seagrass landscapes occur over decadal time scales for seagrass assemblages that exhibit slow rhizome growth. In our landscape simulation, this is a product of increases in size of seagrass patches resulting in coalescence into meadows.

5 Seagrass Seascapes and Faunal Community Structure and Abundance

This section reviews our present knowledge on the effects of seagrass lanscape patern on the fauna found in these shallow subtidal seascapes. The main messages from this research is that the importance of seagrass patchiness, patch size , leading edges and patch isolation in the distribution and abundance of faunal communities is highly variable in time and space and is highly species-specific (Bell et al. 2001; Connolly and Hindell 2006; Bostrom et al. 2006, 2010). Research in this area have suffered from experimental and sampling designs that confound effects of the landscape, habitat complexity, location, depth with time and spatial extent of sampling (Connolly and Hindell 2006). The species specific nature of responses to landscape pattern suggest an understanding of life history, dispersal and recruitment (Bostrom et al. 2010), behavior and predator-prey relations (Hovel and Regan 2008), and the matrix of landscape classes (e.g. seagrass species, reef and sand) within the seascape (Tanner 2006) are required for an effective landscape analysis. Species-specific studies have been the most effective in describing a landscape-organism relationship, for example between the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) and eelgrass (Zostera marina) landscapes (Hovel and Lipcius 2001, 2002; Hovel 2003) and assessing the feedbacks between the organism and the landscape (Hovel and Regan 2008; Mizerek et al. 2011).

The most common method of investigation into the effect of seagrass landscape continuity and fragmentation on faunal communities and populations was to divide the natural seagrass environment into broad categories. For example Fernández et al. (2005) investigated three seagrass patch classes around Capo Feto in the Mediterranean; continuous, large patches (diameter of 3–6 m) and small patches (diameter of 0.5–1.5 m) and found significant differences in the fish assemblage between fragmentation categories with higher species richness in fragmented beds versus continuous meadows. However, fish abundance remained the same across fragmentation classes with smaller individuals found in continuous beds. Interestingly the effect of fragmentation category was found to have a stronger influence on the fish assemblage than the effect of depth. Frost et al. (1999) examined the effects of two levels of seagrass heterogeneity, a continuous seagrass meadow versus a highly fragmented seagrass landscape, on infaunal macroinvertebrate abundance and diversity in Devon in the United Kingdom. Significant multivariate differences in infaunal macroinvertebrate abundances were detected, however, these could not solely be attributed to levels of fragmentation due to the confounding effect of location. Bowden et al. (2001) undertook a similar investigation comparing infaunal macroinvertebrate abundance and diversity in seagrass landscapes with two patch size categories, one comprising patches <10 m in diameter and one patches >30 m in diameter in the Isles of Scilly, south-west England. They reported a significant difference in the macroinvertebrate community structure between sites, patch sizes and in-patch location, and significantly more taxa in large patches than in small, however they did not control for seagrass area. Murphey and Fonseca (1995) in their comparison of low energy continuous seagrass landscapes with higher energy, patchy landscapes in Black Sound in North Carolina, found significantly more pink shrimp, Penaeus duorarum, in the continuous seagrass landscapes. They did control for differences in seagrass area but could not control for differences in location.

Ensuring that seagrass area and the effect of location is accounted for in analyses is a significant, yet common, problem encountered in research into fragmentation of seagrass using natural seagrass beds. One way to control for this is to use artificial seagrass units to create seagrass landscapes that may be manipulated to test for seagrass fragmentation while controlling for area, location and structural complexity. Healey and Hovel (2004) used artificial seagrass units in San Diego Bay, California to examine seagrass heterogeneity while experimentally controlling for seagrass area . Epifaunal abundance and diversity found to be highly variable among the continuous to highly patchy seagrass, among sampling periods and among individual species. However, for two out of three sampling dates, epifaunal diversity was highest and community composition was most dissimilar in patchy or very patchy beds, demonstrating that seagrass patch configuration influenced epifaunal communities independent of seagrass bed area or structural complexity, but was limited by the small scale of treatments where their extent was ≤1 m2.

5.1 Faunal Studies Utilizing Landscape Metrics

In Australia, New Zealand and SE Asia, we have led the way in studies that assess influences of seagrass seascapes on community structure, abundance and movement of seagrass associated fish and invertebrates (Table 9.2).

5.2 Landscape Scale Indices

Adjacency with other classes in the seascape, like mangroves or the mouth of estuaries, were found to be very important for fish and decapod crustaceans (Pittman et al. 2004; Skilleter et al. 2005). The adjacency of mangroves to seagrass meadows was positively related to fish and penaeid prawn abundances and more influential than density of seagrass meadows in Morton Bay. . Similarly, Hannan and Williams (1998) found distance from the mouth of an estuary in NSW was directly correlated to the toatl fish abundance within the estuary.

Generally, most faunal studies have tested correlations among fauna and multiple landscape indices . Pittman et al. (2004) tested patterns in fish and and decapod crustacean community structure and abundance against 15 landscape metrics representing 8 key metric categories: area, patch, edge, core, shape, nearest neighbour, diversity, contagion and interspersion, Similarly, Jackson et al. (2006) tested on fish communities a suit of 12 and Salita et al. (2003) six landscape indices. Those indices that were most influential included landscape composition, landscape heterogeneity (seagrass % cover, number of patches, average patch size , average perimeter:area ratio fractal dimension and the total number of halos within seagrass meadows) , and landscape fragmentation (total edge, interspersion and juxtaposition of patches, patch richness and Shannon diversity) (Table 9.2). Interestingly, their results show that multiple landscape indices account for small to moderate amounts of percent variation, and that in combination rarely account for more than 65% of total variation in fish diversity and abundance.

5.3 Patch Scale Metrics

A number of papers were found to link changes in seagrass associated fauna to patch scale and within patch scale variables, particularly those describing patch size, shape, % seagrass cover and edge effects (Table 9.2). Of these, most found that the responses were quite variable between species and through time and that patch metrics only explained small portions of faunal population or community response.

Strong relationships were found in some studies. For example, Pittman et al. (2004) found fish and penaeid prawn diversity and abundance declined abruptly when seagrass cover in meadows was less than 20% in Moreton Bay. Similarly, Turner et al. (1999) found a significant edge effect effect (within patch, leeward edge and windward edge) on benthic community composition in seagrass meadows in northern New Zealand. Similarly, edge effects were described for fish predation in Shark Bay (Statton et al. 2015) and fish abundance in Indonesia (Vonk et al. 2010).

5.4 Conclusion

The pattern of seagrass distribution and abundance in seagrass landscapes affects associated faunal populations and communities at the seascape, patch and within patch scale , but many of the significant interactions are location and taxon specific making generalizations difficult. Much of the present research has been correlative in nature and points to a need to understand both the specificity of scales in time and space for both the fauna and the seagrass within shallow subtidal seascapes. Hydrodynamic setting and adjacency of other major habitats have been shown to be important in determining faunal utilization of seagrass seascpaes and need further detailed investigation.

6 Summary

A seascape approach is essential to comprehend how the spatial properties of seagrass influence their growth and survivorship, as well as ecological interactions with other marine species e.g. the quality of nursery functions and fisheries productivity of seagrass ecosystems. . In Australia, we have traditionally focused on mapping extensive seagrass habitats and quantifying change in aerial extent, biomass and species composition. Through our extensive mapping efforts, we have been able to perform in depth analysis of spatial structure using landscape indices, which has revealed that no single index can be used to comprehensively quantifying the complex spatial aspects of seagrass seascapes. However, using a combination of Area Weighted Mean Perimeter to Area Ratio and Landscape Division indices provides a comprehensive assessment of spatial structure while avoiding strong correlation among indices. We are at the forefront of modelling landscape level changes, determining the underlying processes responsible for spatio-temporal patterns for some systems (e.g. Owen Anchorage, Moreton Bay). It is clear, however, that the spatial ecology of seagrass remains a critical area. Information on how growth patterns of rhizomes and patterns of seed recruitment contribute to the spatial heterogeneity of seagrass landscapes is sorely lacking, with only one example from Western Australia demonstrating the contribution of asexual and sexual recruitment to patterns in the seascape.

More effort needs to go towards combining remote sensing techniques with landscape ecology and conventional marine ecology, particularly in understanding the processes that influence the flow of energy and material across seascapes and the resulting patterns (Fig. 9.1). This can be achieved through studies of movement ecology, seascape genetics and meta-population modelling , where a combination of approaches will ultimately lead to a more integrating understanding of contemporary as well as evolutionary patterns in seagrass structure (Kendrick et al. 2017). Additionally, a better ecological understanding of the relationships between the indices used to quantify spatial structure and ecological processes must evolve. Future research should specifically aim to clarify (1) The role of structural and functional connectivity at different spatial scales and (2) To what extent can refined indices improve the understanding of habitat connectivity for fisheries or marine zoning. One of the greatest challenges in marine conservation management remains the definition and establishment of habitat protection zones at appropriate scales for local, regional to biogeographic scales.

References

Almela ED, Marbà N, Álvarez E, Santiago R, Martínez R, Duarte CM (2008) Patch dynamics of the Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica: implications for recolonisation process. Aq Bot 89:397–403

Bax N, Kloser R, Williams A, Gowlett-Holmes K, Ryan T (1999) Seafloor habitat definition for spatial management in fisheries: a case study on the continental shelf of southeast Australia. Oceanol Acta 22:705–720

Bell SS, Hicks GRF (1991) Marine landscapes and faunal recruitment a field test with seagrasses and copepods. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 73:61–68

Bell SB, Robbins BD, Jensen SL (1999) Gap dynamics in a seagrass landscape. Ecosystems 2:493–504

Bell SS, Brooks RA, Robbins BD, Fonseca MS, Hall MO (2001) Faunal response to fragmentation in seagrass habitats: implications for seagrass conservation. Biol Cons 100:115–123

Bell SS, Fonseca MS, Stafford NB (2006) Seagrass ecology: new contributions from a landscape perspective. In: Larkum AWD, Robert JO, Duarte CM (eds) Seagrasses: biology, ecology and conservation. Dordrecht, Springer, Netherlands, pp 625–645

Boström C, Jackson EL, Simenstad CA (2006) Seagrass landscapes and their effects on associated fauna: a review. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 68:383–403

Boström C, Törnroos A, Bonsdorff E (2010) Invertebrate dispersal and habitat heterogeneity: expression of biological traits in a seagrass landscape. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 390:106–117

Bowden DA, Rowden AA, Attrill MJ (2001) Effect of patch size and in-patch location on the infaunal macroinvertebrate assemblages of Zostera marina seagrass beds. JExp Mar Biol Ecol 259:133–154

Brouns JJ (1987) Growth patterns in some Indo-West-Pacific seagrasses. Aq Bot 28:39–61

Cambridge ML (1999) Growth strategies of Rottnest Island seagrasses. In DI Walker and FE Wells (eds) The Seagrass Flora and Fauna of Rottnest Island, Western Australia. Western Australia Museum pp 1–24

Cambridge ML, Bastyan GR, Walker DI (2002) Recovery of Posidonia meadows in Oyster Harbour Southwestern Australia. Bull Mar Sci 71:1279–1289

Campey ML, Kendrick GA, Walker DI (2002) Interannual and small-scale spatial variability in sexual reproduction of the seagrasses Posidonia coriacea and Heterozostera tasmanica, southwestern Australia. Aq Bot 74:287–297

Canal-Vergés P, Potthoff M, Hansen FT, Holmboe N, Rasmussen EK, Flindt MR (2014) Eelgrass re-establishment in shallow estuaries is affected by drifting macroalgae—evaluated by agent-based modeling. Ecol Model 272:116–128

Carruthers TJB, Dennison WC, Kendrick GA, Waycott M, Walker DI, Cambridge ML (2007) Seagrasses of south–west Australia: a conceptual synthesis of the world’s most diverse and extensive seagrass meadows. JExp Mar Biol Ecol 350:21–45

Clarke SM, Kirkman H (1989) Seagrass dynamics. In: Larkum AWD, McComb AJ, Shepherd SA (eds) Biology of the seagrasses: a treatise on the biology of seagrasses with special reference to the Australian region. Elsevier/North Holland, Amsterdam, pp 304–345

Connolly RM, Hindell JS (2006) Review of nekton patterns and ecological processes in seagrass landscapes. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 68:433–444

D’Eon R, Glen SM (2000) Perceptions of landscape patterns: do the numbers count? Forest Chronicle 76:475–480

DeAngelis DL, Grimm V (2014) Individual-based models in ecology after four decades. F1000Prime Reports, vol 6, p 39

Dekker AG, Brando VE, Anstee JM (2005) Retrospective seagrass change detection in a shallow coastal tidal Australian lake. Remote Sens Environ 97:415–433

Duarte CM, Sand-Jensen K (1990) Seagrass colonization: patch formation and patch growth of Cymodocea nodosa. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 65:193–200

Duarte CM, Terrados J, Agawin NSR, Fortes MD, Bach S, Kenworthy WJ (1997) Response of a mixed Phillippine seagrass meadow to experimental burial. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 147:285–294

Durako MJ, Hall MO, Merello M (2002) Patterns of change in the seagrass dominated Florida Bay hydroscape. In: Porter JW, Porter KG (eds) The Everglades, Florida Bay, and coral reefs of the Florida Keys: an ecosystem sourcebook. CRC Press, Washington DC, pp 523–537

Fernández TV, Milazzo M, Badalamenti F, D’Anna G (2005) Comparison of the fish assemblages associated with Posidonia oceanica after the partial loss and consequent fragmentation of the meadow. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 65:645–653

Fonseca MS, Bell SS (1998) Influence of physical setting on seagrass landscapes near Beaufort, North Carolina. USA. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 171:109

Fonseca M, Whitfield PE, Kelly NM, Bell SS (2002) Modelling seagrass landscape pattern and associated ecological attributes. EcolAppl 12:218–237

Frederiksen M, Krause-Jensen D, Holmer M, Laursen JS (2004a) Spatial and temporal variation in eelgrass (Zostera marina) landscapes: influence of physical setting. Aquat Bot 78:147–165

Frederiksen M, Krause-Jensen D, Holmer M, Laursen JS (2004b) Long-term changes in area distribution of eelgrass (Zostera marina) in Danish coastal waters. Aquat Bot 78:167–181

Freitas R, Rodrigues AM, Quintino V (2003) Benthic biotopes remote sensing using acoustics. J Exp Marine Biol Ecol 285–286:339–353

Friedlander A, Nowlis JS, Sanchez JA, Appeldoorn R, Usseglio P, McCormick C, Bejarano S, Mitchell-Chui A (2003) Designing effective marine protected areas in Seaflower Biosphere Reserve, Colombia, based on biological and sociological information. Conserv Biol 17:1769–1784

Frost MT, Rowden AA, Attrill MJ (1999) Effect of habitat fragmentation on the macroinvertebrate infaunal communities associated with the seagrass Zostera marina L. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 9:255–263

Garrabou J, Riera J, Zabala M (1998) Landscape pattern indices applied to Mediterranean subtidal rocky benthic communities. Landscape Ecol 13:225–247

Garza-Perez JR, Lehmann A, Arias-Gonzalez JE (2004) Spatial prediction of coral reef habitats: integrating ecology with spatial modelling and remote sensing. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 269:141–152

Gustafson EJ (1998) Quantifying landscape spatial pattern: what is the state of the art? Ecosystems 1:143–156

Gustafson EJ, Parker GR (1992) Relationships between landcover proportion and indices of landscape spatial pattern. Landscape Ecol 7:101–110

Haines-Young R, Chopping M (1996) Quantifying landscape structure: a review of landscape indices and their application to forested landscapes. Prog Phys Geogr 20:418–445

Hannan JC, Williams RJ (1998) Recruitment of juvenile marine fishes to seagrass habitat in a temperate Australian estuary. Estuaries 21:29–51

Hargis CD, Bissonette JA, David JL (1998) The behaviour of landscape metrics commonly used in the study of habitat fragmentation. Landscape Ecol 13:167–186

Hastings A, Byers JE, Crooks JA, Cuddington K, Jones CG, Lambrinos JG, Talley TS, Wilson WG (2007) Ecosystem engineering in space and time. Ecol Lett 10:153–164

Healey D, Hovel KA (2004) Seagrass bed patchiness: effects on epifaunal communities in San Diego Bay, USA. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 313:155–174

Holmes KW, Van Niel KP, Kendrick GA, Radford B (2007) Probabilistic large-area mapping of seagrass species distributions. Aquat Conserv: Mar Freshw Ecosyst 17:385–407

Holmes KW, Van Niel KP, Radford B, Kendrick GA, Grove SL (2008) Modelling distribution of marine benthos from hydroacoustics and underwater video. Cont Shelf Res 28:1800–1810

Hovel KA (2003) Habitat fragmentation in marine landscapes: relative effects of habitat cover and configuration on juvenile crab survival in California and North Carolina seagrass beds. Biol Cons 110:401–412

Hovel KA, Lipcius RN (2001) Habitat fragmentation in a seagrass landscape: patch size and complexity control blue crab survival. Ecology 82:1814–1829

Hovel KA, Lipcius RN (2002) Effects of seagrass habitat fragmentation on juvenile blue crab survival and abundance. J Exp Marine Biol Ecol 271:75–98

Hovel KA, Regan H (2008) Using an individual-based model to examine the roles of habitat fragmentation and behavior on predator–prey relationships in seagrass landscapes. Landscape Ecol 23:75–89

Hovey RK, Van Niel KP, Bellchambers LM, Pember MB (2012) Modelling deep water habitats to develop a spatially explicit, fine scale understanding of the distribution of the western rock lobster Panulirus cygnus. PLoS ONE 7(4):e34476. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034476

Hovey RK, Zavala Perez A, Statton J, Fraser MW, Ruiz Montoya L, Rees M, Stoddart J, Kendrick GA (2015) Strategy for assessing impacts in highly seasonal tropical seagrasses. Mar Pollut Bull 101:594–599

Hutchinson GE (1953) The concept of pattern in ecology. Proc Acad Nat Sci Philadelphia 104:1–12

Hyland SJ, Courtney AJ, Butler CT (1989) Distribution of seagrass in the Moreton region from Coolangatta to Noosa. Queensland Government Department of Primary Industries, Information Series Q189010. Queensland Government, Brisbane, Australia

Inglis GJ (2000a) Variation in the recruitment behaviour of seagrass seeds: implications for population dynamics and resource management. Pac Conserv Biol 5:251–259

Inglis GJ (2000b) Disturbance-related heterogeneity in the seed banks of a marine angiosperm. J Ecol 88:88–99

Irlandi EA (1994) Large- and small-scale effects of habitat structure on rates of predation: how percent coverage of seagrass affects rates of predation and siphon nipping on an infaunal bivalve. Oecologia 98:176–183

Irlandi EA, Ambrose WG, Orlando BA (1995) Landscape ecology and the marine environment—how spatial configuration of seagrass habitat influences growth and survival of the bay scallop. Oikos 72:307–313

Jackson EL, Attrill MJ, Rowden AA, Jones MB (2006) Seagrass complexity hierarchies: influence on fish groups around the coast of Jersey (English Channel). J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 330:38–54

Jaeger JAG (2000) Landscape division, splitting index, and effective mesh size: new measures of landscape fragmentation. Landscape Ecol 15:115–130

Jelbart JE, Ross PM, Connolly RM (2006) Edge effects in seagrass landscapes: an experimental test using fish. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 319:93–102

Jorge LAB, Garcia GJ (1997) A study of habitat fragmentation in Southeastern Brazil using remote sensing and geographic information systems (GIS). For Ecol Manage 98:35–47

Kendrick GA, Eckersley J, Walker DI (1999) Landscape-scale changes in seagrass distribution over time: a case study from Success Bank, Western Australia. Aquat Bot 65:293–309

Kendrick GA, Hegge BJ, Wyllie A, Davidson A, Lord DA (2000) Changes in seagrass cover on Success and Parmelia Banks, Western Australia between 1965 and 1995. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 50:341–353

Kendrick GA, Aylward M, Hegge BJ, Cambridge ML, Hillman KA, Wyllie A, Lord DA (2002) Changes in seagrass coverage in Cockburn Sound, Western Australia between 1967 and 1999. Aquat Bot 73:75–87

Kendrick GA, Marba N, Duarte CM (2005a) Modelling formation of complex topography by the seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 65:717–725

Kendrick GA, Duarte CM, Marba N (2005b) Clonality in seagrasses, emergent properties and seagrass landscapes. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 290:291–296

Kendrick GA, Holmes KW, Van Niel KP (2008) Multi-scale spatial patterns of three seagrass species with different growth dynamics. Ecography 31:191–200

Kendrick GA, Waycott M, Carruthers T, Cambridge ML, Hovey R, Krauss S, Lavery P, Les D, Lowe R, Mascaró O, Ooi Lean Sim J, Orth RJ, Rivers D, Ruiz-Montoya L, Sinclair EA, Statton J, van Dijk JK, Verduin J (2012) The central role of dispersal in the maintenance and persistence of seagrass populations. Bioscience 62:56–65

Kendrick GA, Orth RJ, Statton J, Hovey R, Ruiz-Montoya L, Lowe R, Krauss S, Sinclair EA (2017) Demographic and genetic connectivity: the role and consequences of reproduction, dispersal and recruitment in seagrasses. Biol Rev 92:921–938

Kenny AJ, Cato I, Desprez M, Fader G, Schu¨ttenhelm RTE, Side J (2003) An overview of seabed-mapping technologies in the context of marine habitat classification. ICES J Mar Sci 60:411–418

Kilminster K, McMahon K, Waycott M, Kendrick GA, Scanes P, McKenzie L, O’Brien KR, Lyons M, Ferguson A, Maxwell P, Glasby T, Udy J (2015) Unraveling complexity in seagrass systems for management: Australia as a microcosm. Sci Total Environ 534:97–109

Kirkman H (1985) Community structure in seagrasses in southern Western Australia. Aquat Bot 21:363–375

Kirkman H (1998) Pilot experiments on planting seedlings and small seagrass propagules in Western Australia. Marine Poll Bull 37:460–467

Kreft JU, Booth G, Wimpenny JWT (1998) Bacsim, a simulator for individual-based modelling of bacterial colony growth. Microbiology 144:3275–3287

Larkum AWD, West RJ (1990) Long-term changes of seagrass meadows in Botany Bay, Australia. Aquat Bot 37:55–70

Levin SA, Paine RT (1974) Disturbance, patch formation, and community structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 71:2744–2747

Li BL, Archer S (1997) Weighted mean patch size: a robust index for quantifying landscape structure. Ecol Model 102:353–361

Luna F, Stefannson B (2000) Economic simulations in SWARM: agent-based modelling and object oriented programming, vol 14. Kluwer Academic Publishers

Lyons MB, Roelfsema CM, Phinn SR (2013) Towards understanding temporal and spatial dynamics of seagrass land—scapes using time-series remote sensing. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 120:42–53

Lyons MB, Roelfsema CM, Kovacs E, Samper-Villarreal J, Saunders M, Maxwell P, Phinn SR (2015) Rapid monitoring of seagrass biomass using a simple linear modelling approach, in the field and from space. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 530:1–14

Marba N, Duarte CM (1995) Coupling of seagrass (Cymodocea nodosa) patch dynamics to subaqueous dune migration. J Ecol 83:381–389

Marba N, Duarte CM (1998) Rhizome elogation and seagrass clonal growth. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 174:269–280

Marba N, Walker DI (1999) Growth, flowering, and population dynamics of temperate Western Australian seagrasses. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 184:105–118

McGarigal K (2002) Landscape pattern metrics. In AH El-Shaarawi and WW Piegorsch (eds) Encyclopedia of Environmentrics, vol 2, Wiley, Sussex, pp 1135–1142

McGarigal K, Marks BJ (1995) FRAGSTATS: Spatial pattern analysis program for quantifying landscape structure. US Forest Service General Technical Report PNW p 122

McMahon K, van Dijk K-J, Ruiz-Montoya L, Kendrick G, Krauss SL, Waycott M, Verduin J, Lowe R, Statton J, Brown E, Duarte C (2014) The movement ecology of seagrasses. Proc R Soc B 281. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.0878

McRea JE Jr, Greene HG, O’Connell VM, Wakefield WW (1999) Mapping marine habitats with high resolution sidescan sonar. Oceanol Acta 22:679–686

Mizerek T, Regan HM, Hovel KA (2011) Seagrass habitat loss and fragmentation influence management strategies for a blue crab Callinectes sapidus fishery. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 427:247–257

Murphey PL, Fonseca MS (1995) Role of high and low energy seagrass beds as nursery areas for Penaeus duorarum in North Carolina. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 121:91–98

Olesen B, Sand-Jensen K (1994) Patch dynamics of eelgrass Zostera marina. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 106:147

O’Neill RV, Riitters KH, Wickham JD, Jones KB (1999) Landscape pattern metrics and regional assessment. Ecosys Health 5:225–233

Ooi JLS, Van Niel KP, Kendrick GA, Holmes KW (2014) Spatial structure of seagrass suggests that size-dependent plant traits have a strong influence on the distribution and maintenance of tropical multispecies meadows. PLoS ONE 9:e86782. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086782

Orth RJ, Carruthers TJB, Dennison WC, Duarte CM, Fourqurean JW, Heck KL, Hughes AR, Kendrick GA, Kenworthy WJ, Olyarnik S, Short FT, Waycott M, Williams SL (2006a) A global crisis for seagrass ecosystems. Bioscience 56:987–996

Orth RJ, Kendrick GA, Marion SR (2006b) Predation on Posidonia australis seeds in seagrass habitats of Rottnest Island, Western Australia: patterns and predators. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 313:105–114

Pastor J (2011) Mathematical ecology of populations and ecosystems. Wiley

Phinn SR, Roelfsema CM, Dekker AG, Brando V, Anstee J (2008) Mapping seagrass species, cover and biomass in shallow waters: an assessment of satellite multi-spectral and airborne hyper-spectral imaging systems in Moreton Bay (Australia). Remote Sens Environ 112:3413–3425

Pickett STA, White PS (1985) The ecology of natural disturbance and patch dynamics. Academic Press, New York

Pittman SJ, McAlpine CA, Pittman KM (2004) Linking fish and prawns to their environment: a hierarchical landscape approach. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 283:233–254

Quammen ML, Onuf CP (1993) Laguna Madre: seagrass changes continue decades after salinity reduction. Estuaries 16:302–310

Rasheed MA (1999) Recovery of experimentally created gaps within a tropical Zostera capricorini (Aschers) seagrass meadow, Queensland Australia. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 235:183–200

Reed RA, Johnson-Barnard J, Baker W (1996) Fragmentation of a forested rocky mountain landscape, 1950–1993. Biol Cons 75:267–277

Renton M, Airey M, Cambridge ML, Kendrick GA (2011) Modelling seagrass growth and development to evaluate transplanting strategies for restoration. Ann Botany 108:1213–1223

Riitters KH, O’Neill RV, Hunsaker CT, Wickham JD, Yankee DH, Timmins SP (1995) A factor analysis of landscape pattern and structure metrics. Landscape Ecol 10:23–39

Rivers DO, Kendrick GA, Walker DI (2011) Microsites play an important role for seedling survival in the seagrass Amphibolis antarctica. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 401:29–35

Robbins BD, Bell SS (2000) Dynamics of a subtidal seagrass landscape: seasonal and annual change in relation to water depth. Ecology 81:1193–1205

Robins BD, Bell SS (1994) Seagrass landscapes: a terrestrial approach to the marine subtidal environment. Trends Ecol Evolut 9:301–304

Roelfsema C, Lyons M, Kovacs E, Maxwell P, Saunders M, Samper-Villarreal J, Phinn S (2014) Multi-temporal mapping of seagrass cover, species and biomass: a semiautomated object based image analysis approach. Remote Sens Environ 150:172–187

Rollon RN, De Ruyter Van Steveninck ED, Van Vierssen W, Fortes MD (1998) Contrasting recolonization strategies in multi-species seagrass meadows. Marine Poll Bull 37:450–459

Salita JT, Ekau W, Saint-Paul U (2003) Field evidence on the influence of seagrass landscapes on fish abundance in Bolinao, northern Philippines. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 247:183–195

Santos RO, Lirman D, Pittman SJ (2015) Long-term spatial dynamics in vegetated seascapes: fragmentation and habitat loss in a human-impacted subtropical lagoon. Mar Ecol 36:1–15

Saura S (2002) Effects of minimum mapping unit on land cover data spatial configuration and composition. Int J Remote Sens 23:4853–4880

Schumaker NH (1996) Using landscape indices to predict habitat connectivity. Ecology 77:1210–1225

Seddon S, Connolly RM, Edyvane KS (2000) Large-scale seagrass dieback in northern Spencer Gulf, South Australia. Aquat Bot 66:297–310

Short FT, Burdick DM (1996) Quantifying eelgrass habitat loss in relation to housing development and nitrogen loading in Waquoit Bay, Massachusetts. Estuaries 19:730–739

Sintes T, Marba N, Duarte CM, Kendrick G (2005) Non-linear processes in seagrass colonization explained by simple clonal growth rules. Oikos 108:165–175

Skilleter GA, Olds A, Loneragan NR, Zharikov Y (2005) The value of patches of intertidal seagrass to prawns depends on their proximity to mangroves. Mar Biol 147(2):353–365

Sleeman JC, Boggs GS, Radford BC, Kendrick GA (2005) Using agent-based models to aid reef restoration: enhancing coral cover and topographic complexity through the spatial arrangement of coral transplants. Restoration Ecol 13:685–694

Smith NM, Walker DI (2002) Canopy structure and pollination biology of the seagrasses Posidonia australis and P. sinuosa (Posidoneaceae). Aquat Bot 74:57–70

Smith TM, Hindell JS, Jenkins GP, Connolly RM, Keough MJ (2011) Edge effects in patchy seagrass landscapes: the role of predation in determining fish distribution. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 399:8–16

Soberón J, Peterson AT (2005) Interpretation of models of fundamental ecological niches and species’ distributional areas. Biodiversity Informatics 2:1–10

Solan M, Germano JD, Rhoads DC, Smtih C, Michaud E, Patty D, Wenzhöfer F, Kennedy B, Henriques C, Battle E, Carey D, Iocco L, Valente R, Watson J, Rodenberg R (2003) Towards a greater understanding of pattern, scale, and process in marine benthic systems: a picture is worth a thousand worms. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 285–286:313–338

Statton J, Gustin-Craig S, Dixon K, Kendrick GA (2015) Edge effects along a seagrass margin result in an increased grazing risk on Posidonia australis transplants. PLoS ONE 10:e0137778. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137778

Steele JH (1978) Spatial pattern in plankton communities. Plenum, New York

Suykerbuyk W, Bouma TJ, Govers LL, Giesen K, de Jong DJ, Herman P, van Katwijk MM (2016) Surviving in changing seascapes: sediment dynamics as bottleneck for long-term seagrass presence. Ecosystems 19(2):296–310

Tanner JE (2005) Edge effects on fauna in fragmented seagrass meadows. Austral Ecol 30:210–218

Tanner JE (2006) Landscape ecology of interactions between seagrass and mobile epifauna: the matrix matters. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 68:404–412

Turner MG (1989) Landscape ecology: the effect of pattern on process. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 20:171–197

Turner SJ, Hewitt JE, Wilkinson MR, Morrisey DJ, Thrush SF, Cummings VJ, Funnell G (1999) Seagrass patches and landscapes: the influence of wind-wave dynamics and hierarchical arrangements of spatial structure on macrofaunal seagrass communities. Estuaries 22:1016–1032

van Teeffelen AJA, Ovaskainen O (2007) Can the cause of aggregation be inferred from species distributions? Oikos 116:4–16

Vidondo B, Duarte CM, Middelboe AL, Stefansen K, Luetzen T, Nielsen SL (1997) Dynamics of a landscape mosaic: Size and age distributions, growth and demography of seagrass Cymodocea nodosa patches. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 158:131–138

Villa F, Costanza R (2000) Design of multi-paradigm integrating modelling tools for ecological research. Environ Model Softw 15:169–177

Vonk JA, Christianen MJA, Stapel J (2010) Abundance, edge effect, and seasonality of fauna in mixed-species seagrass meadows in southwest Sulawesi, Indonesia. Marine Biology Research 6:282–291

Wagner HH, Fortin MJ (2005) Spatial analysis of landscapes: concepts and statistics. Ecology 86:1975–1987

Walker DI, Hillman KA, Kendrick GA, Lavery P (2001) Ecological significance of seagrasses: assessment for management of environmental impact in Western Australia. Ecol Eng 16:323–330

Waycott MW, Walker DI, James SH (1996) Genetic uniformity in Amphibolis antarctica, a dioecious seagrass. Heredity 76:578–585

Wedding LM, Lepczyk CA, Pittman SJ, Friedlander AM, Jorgensen S (2011) Quantifying seascape structure: extending terrestrial spatial pattern metrics to the marine realm. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 427:219–232

Williams SL (1990) Experimental studies of Caribbean seagrass bed development. Ecol Monograph 60:449–469

Wong S, Anand M, Bauch CT (2011) Agent-based modelling of clonal plant propagation across space: recapturing fairy rings, power laws and other phenomena. Ecological Informatics 6:127–135

Young PC, Kirkman H (1975) The seagrass communities of Moreton Bay, Queensland. Aquat Bot 1:191–202

Zhang X, Drake NA, and Wainwright J (2013) Spatial modelling and scaling issues. In: Environmental Modelling. Wiley, Ltd pp 69–90

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kendrick, G.A., Hovey, R.K., Lyons, M., Roelfsema, C., Montoya, L.R., Phinn, S. (2018). Australian Seagrass Seascapes: Present Understanding and Future Research Directions. In: Larkum, A., Kendrick, G., Ralph, P. (eds) Seagrasses of Australia. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71354-0_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71354-0_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-71352-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-71354-0

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)