Abstract

The ASSIST-ME project has a dual aim: (1) to provide a research base on the effective uptake of formative and summative assessment for inquiry-based, competence-oriented Science, Technology and Mathematics (STM) education and (2) to use this research base to give policy-makers and other stakeholders guidelines for ensuring that assessment enhances learning in STM education. This chapter describes how the second aim, the policy-oriented aspects, was dealt with in ASSIST-ME. It describes the establishment of National Stakeholder Panels (NSP) through the use of social network analysis as well as the work and outcomes of the national NSPs. In a wider perspective, it analyses how research results have and can influence STM education, both the educational practices and the political climate and decisions framing education. At this point, the chapter goes beyond ASSIST-ME and draws upon other project experiences across Europe. Finally, the policy recommendations for the transformation process based on the ASSIST-ME experiences will be put forward.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

When it was set up in 2012, the ASSIST-ME project was responding to a perceived need within education in Europe to reform evaluation and assessment practices. Some years earlier, in 2009, the OECD had launched the programme ‘Review on Evaluation and Assessment Frameworks for Improving School Outcomes’ (www.oecd.org/edu/evaluationpolicy) ‘designed to respond to the strong interest in evaluation and assessment issues evident at national and international levels’ (ibid.). As stated in the final report, one of the key issues dealt with was: ‘How can assessment and evaluation policies work together more effectively to improve student outcomes in primary and secondary schools?’ (OECD 2013). The reports expressed a growing understanding among the OECD countries that evaluation and assessment systems are key components in improving school systems. Together with a number of other reports aimed at education policy-makers, the need for a greater focus on formative assessment and its integration with summative assessment became more and more obvious (Looney 2011; OECD/CERI 2005). A report ‘emphasise[d] the importance of seeing evaluation and assessment not as ends in themselves, but instead as important tools for achieving improved student outcomes’ (OECD 2011, p.1). This position suggests an emerging awareness among policy-makers that evaluation for accountability reasons has, to a large degree, hindered formative processes.

The importance of assessment for learning has, at the same time, become widely known in education circles, thanks, to some degree, to John Hattie’s meta-analysis Visible Learning (Hattie 2008), which showed that formative assessment is one of the most effective ways to enhance student learning.

Especially within science education, both researchers and teachers have for a long time been complaining over the many tests often testing only rote learning and simple knowledge (Harlen 2007), and reports have pointed at solutions:

Tests are dominated by questions that require recall – a relatively undemanding cognitive task and, in addition, often have limited validity and reliability. … Transforming this situation requires the development of assessment items that are more challenging; cover a wider range of skills and competencies; and make use of a greater variety of approaches – in particular, diagnostic and formative assessment. (Osborne and Dillon 2008, p. 8)

This growing imbalance between a dominating test system assessing relatively simple skills and the need for introducing formative assessments able to capture more advanced competences has been a focus for EU projects such as SAILS (http://sails-project.eu/). The ASSIST-ME project responded to a call from the European Union’s research and innovation funding programme for 2007–2013, the so-called FP7 programme. The call recognised that merely developing new assessment items was not sufficient; it also had to be a political priority to reform the educational system to give room for formative processes in a system with strong emphasis on summative assessments. The FP7 call contained an explicit demand to enter into the political world, and some of the expected outcomes were identified:

The research should be ‘use-inspired’ and lead to identification of the factors (including cultural) that undermine the effective uptake of formative assessment appropriately combined with summative assessment in different contexts […] The actions should include policy recommendations and appropriate dissemination activities […] the project will provide policy makers with data and guidelines for an informed decision making.

The ASSIST-ME project has taken up these challenges. The project partners defined dual aims: (1) to provide a research base on the effective uptake of formative and summative assessment for inquiry-based, competence-oriented Science, Technology and Mathematics education in primary and secondary education in different educational contexts in Europe and (2) to use this research base to give policy-makers and other stakeholders guidelines for ensuring that assessment enhances learning in STM education (Dolin 2013, p. 5).

This chapter describes how the second aim, the policy-oriented aspects, was dealt with in ASSIST-ME. It will put the project experiences into a wider European perspective by referring to other initiatives. A key focus is on how educational policies may encourage or restrict the contribution that assessment might make to students’ learning. In many countries, the formative-summative dichotomy has, to a large degree, been created by the national use of externally based summative assessments. We know that such tests often distort the learning agenda while being inadequate in validity and even often in reliability (see Chap. 3 in this volume). Various examples will be given from different national contexts of the barriers to introducing more formative assessment, and also examples of national policies given more emphasis to the formative aspects, and maybe combining them with summative assessments.

In accordance with the dual goals of the ASSIST-ME project, it was organised as two parallel strands. In one strand ASSIST-ME teachers and researchers worked together in teacher action research processes designing and implementing formative assessment processes. This work was organised in local working groups (LWGs) which met regularly to prepare and discuss the implementation. Researchers analysed data to answer the research questions. This work is presented in Chapters. 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 in this volume. The other strand dealt with the policy aspects of the project. In each participating country, National Stakeholder Panels (NSPs) were established involving representatives from different stakeholder groups influencing educational decisions in the country. In this chapter, we will describe how the project used social network analysis (Scott and Carrington 2011) for identifying and selecting NSP members as well as the work and outcomes of the national NSPs. We will also show how the NSPs have given feedback to, and informed, the ASSIST-ME project. In a wider perspective, we will analyse how research results have and can influence STM education, both the educational practices and the political climate and decisions framing education. At this point, we will go beyond ASSIST-ME and draw upon other project experiences across Europe. Finally, the policy recommendations for the transformation process based on the ASSIST-ME experiences will be put forward.

Linking Teachers, Researchers and Policy-Makers

Despite the increased focus in the last decade on using research as an evidence base for educational decisions, it is not the norm for educational research projects to explicitly address policy issues. Most researchers see it as a virtue to separate research, seen as objective and independent, from policy, which is interwoven with interests and weakly underpinned opinions. Of course, the reality is far more complicated. Most research is financed by foundations, companies, interest groups or a public programme – with specific aims and specific expectations in terms of the product – and researchers are therefore becoming more aware of the impact of their findings and of the necessity of engaging in dialogue with policy.

Research tells us, however, that it is not easy for research to affect policy due to different logics and different discourses (Fensham 2009). In his article ‘Speaking Truth to Power with Powerful Results: Impacting Public Awareness and Public Policy’, Mack Shelley II (2009) underlines the need for eclecticism in research and its interface with expertise and policy. The point is that to communicate research findings to decision-makers, you need to break down the barriers between the research world and the policy world through better communication and an understandable and usable message. This can only be achieved if the two sides meet to exchange ideas and understandings and accept each other’s respective capacities and influence.

Education researchers primarily report their results to the research community which is most often isolated from the political processes, not because researchers have little knowledge about their national policy matters but to ensure their academic independence. This dissociation between research and policy goes back to the building of the independent universities and their insistence on academic freedom.

One of the consequences of this approach has been the development of different logics and discourses within these separated areas of activity – with the result that educational research sometimes has little influence on policy. To change this situation, it is necessary to understand how policy is made and how it is implemented. It is also important to know the discourse of policy and to communicate results in a way politicians can understand and use. If you want influence on educational policy, you need to engage directly with the relevant policy-makers in a language they can understand – it is of no use to stand outside talking to each other in your own jargon.

In broad terms, both educational research and education policy development aim to contribute towards improved teacher effectiveness as well as enhanced student learning, creativity and emergent autonomy. Educational research is constrained by methodology and the reliability of evidence. Policy-making is constrained, additionally, by convention, existing practices, finite resources, administrative structures, professional capacities and stakeholder interests.

Improving student learning in STM is an immensely challenging goal. As they grow, children develop their own perspectives, styles and interests. The extent to which they purposefully engage with science learning has a crucial influence on their progress. Meeting the aim of attaining a minimum level of science literacy for all requires concerted effort on behalf of teachers and families over extensive periods of time. Many things can and often do go wrong. Systemic constraints add an extra level of complexity to this inherently challenging task.

The Science Education Expert Group brought together by the European Commission sought to critically analyse prior efforts to promote reform in STEM education and to utilise diverse perspectives in using existing evidence to formulate recommendations and priorities for renewed efforts. This dual emphasis on diversity of participation and evidence-informed policy development is valuable in providing a bridge between science education research and an informed approach to formulating future priorities.

European policy-making has a natural ally in international research activities and communities such as European Science Education Research Association that promote these activities. Collaboration across different educational systems adds value and thoughtfulness to reform efforts, especially if that collaboration takes the available research into account. In addition, it has the potential to promote learning from best practices. Even so, the divergent priorities of research and policy reform sustain widely differing cultures in the communities that promote them sometimes with deep mistrust between them. In this sense, it is not surprising that the gap between research and practice appears to be widening.

The subsidiarity principle places responsibility for European education at the level of Member States. This tends to severely limit the power of European policy-making to influence classroom practices. At local level, the divergence between science education research and policy tends to be even greater. At this level, administrative constraints, conventions and stakeholder interests tend to be more pronounced with a correspondingly stronger influence in the majority of educational systems.

Where does all this leave us?

The need for evidence-informed policy development is stronger than ever. To respond to this, there needs to be a concerted effort to strengthen capacities and promote structures that enhance bilateral communication between policy-makers and educational researchers. Formulating measurable objectives and committing to them over extensive periods of different politicians is equally important for this shift to happen.

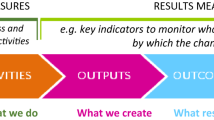

The same situation of discursive misunderstanding and deeply rooted mistrust also applies to the relationship between teachers and policy-makers and to a lesser extent to the relationship between researchers and teachers. One model for these relationships is a triangle with research, policy and practice at the corners (see Fig. 10.1).

In the model, researchers and teachers work together to define and carry out research that both parties find useful. The work is mediated by policy input. Researchers and policy-makers exchange research findings and policy demands for new research, with teachers being involved in the communication process. Teachers and policy-makers build a mutual respect for each other’s profession and recognise each other’s distinct roles, while researchers can deliver knowledge to the process. For each of the agents, it is a question of changing their respective areas of practice with due respect to the legitimate interest and expertise of the other two agents. Researchers need to pursue research questions relevant to teachers and policy-makers. Teachers need to change teaching practices in the light of research and policy demands based on societal decisions. Policy-makers need to change educational policy in accordance with research and with teacher requirements for fulfilling their job.

The ASSIST-ME project has mainly worked on the research-teacher and the research-policy relations. The first relation was practised in the LWGs, and the links from teachers to policy were managed by the researchers, although teachers participated in some NSP meetings. But the fact that teachers’ voices were reported to policy-makers by researchers did put the onus on the researchers to get it right. The research-policy relation was practised in the NSPs, and in this chapter, we will mainly deal with the work of the NSPs and refer to some of the policy-related discussions in the LWGs.

The ASSIST-ME Approach to Policy Issues

The NSPs played a pivotal role in including policy-makers in the project and in giving them influence and co-ownership of the research findings. The starting point was an acknowledgement that policy-makers were looking for solutions to problems they realise were important. We also knew from our experience that there were no quick fixes; one piece of evidence wouldn’t do the trick – we needed sustained lobbying, which required consistent involvement from the selected representatives from the different stakeholders. We believed that most stakeholders want to influence policy not for their own self-interest but for what they saw as higher motives, often coloured by their organisational background. The challenge was how do you systematically identify the people who represent key stakeholders, how do you make them interested in getting involved and how do you sustain their interest throughout the project’s lifetime?

Selecting Key Stakeholders Through Network Analysis

The identification of key people influencing STM education was managed through a social network analysis process. The method is described in detail in ASSIST-ME Deliverable D5.1, downloadable from www.assistme.ku.dk, and Fig. 10.2 illustrates the steps in the method. The first list of Danish stakeholder candidates was drawn up by selected national researchers. They were told that the stakeholder network should map out the people in different organisations – not the organisations themselves – who were influential in making educational changes.

Based on this first list, we identified the following groups of key stakeholders in the project who it was crucial to involve in any project aimed at influencing STM education:

-

Government and municipalities (central as well as local levels): Governments drive policy development in the area of innovative science strategies at a general level, such as the role of assessment, the introduction of new assessment methods, the overall curriculum goals, the framing conditions for teacher education and in-service training, etc. Depending on the educational system and culture, municipalities and local authorities can be crucial in facilitating cultural change in STM education.

-

Media: Journalists in the leading print media and broadcasting corporations have substantial influence on policy and decision-makers, especially with respect to agenda setting. Close communication with media representatives is crucial in order to facilitate the public discussions of how assessment strategies influence the outcomes of teaching. This approach will support policy-makers in working with cultural change in STM education.

-

Business and industry: With the key role STM education plays in the economic development of all EU countries, organisations representing business interests have a strong incentive to be involved in the project. In some countries, such as Denmark, private foundations, often with strong connections to private companies, also have a major influence in deciding which areas and development trends they give funding for development and research.

-

Teachers: Teachers are primary agents for implementing real changes in the classroom. It is vitally important that they are directly or indirectly involved in any education research projects. This involvement may be via those teachers well known for their contributions to public discourse, or, more importantly, those who are involved in teacher organisations. In Denmark, teachers are organised in two teacher unions, one for compulsory school teachers (primary and lower secondary level) and one for upper secondary school levels. Both have significant influence on educational policy. As well as being members of unions, most teachers are also members of a subject teacher association, which are involved in curriculum changes.

-

School leaders and school owners: School leaders are usually responsible for organising and supporting implementation of most educational changes. Their involvement is essential in any project leading to policy recommendations. Depending on national conditions, school owners are equally important. In Denmark, compulsory schools are mostly ‘owned’ (meaning financed and steered on major issues) by the municipalities, while some compulsory schools are private, and nearly all upper secondary schools (gymnasiums) are independent units under national legislation.

-

Teacher trainers and professional development providers: Teacher trainers and professional development providers should be conversant and fully aware of the project objectives and findings. They will then be able to adopt and adapt those aspects that will encourage more widespread uptake of the project ideas and findings.

-

Research communities of STM education: The results of the project have been disseminated in conference presentations and by publishing in journal papers. Feedback from the research community is crucial in validating the project’s findings in a wider context.

These groupings were communicated to the ASSIST-ME partners, and they guided the partners in their selection of NSP members so as to have as broad a representation as possible.

In each country, an iterative process was carried through. The ideal process is illustrated in Fig. 10.3, and due to unforeseen obstacles in the partner countries, the process varied a bit from country to country. The ideal process has these phases:

-

A.

The researchers made up a list of stakeholders covering the above groupings, including the name, email address and to which organisation the stakeholder belonged. In a country like Denmark, we expected the list to be comprised of approximately 500 persons.

-

B.

Each person on the list was sent a SurveyXact questionnaire (in the national language) asking: ‘Which persons do you consider to have impact on changing assessment practices at the school, local and national level?’ For each person they named, they gave an email address (if possible) and organisation affiliation. They were also asked to indicate whether the person had impact on changing assessment practices at the school level, local level or national level.

-

C.

Based on the survey data, the Danish group produced a network of stakeholder candidates and gave it a first analysis in collaboration with the national researchers.

-

D.

Stakeholders who held central positions in the network of stakeholder candidates were listed, i.e. persons with many incoming connections but also with a large diversity in types of stakeholder candidates to which they were connected. The selection was based on a dialogue between the ASSIST-ME partners and the Danish team. If the ASSIST-ME partner believed that an important stakeholder candidate was missing from the network, the stakeholder could be included in the new list of stakeholders. The number of stakeholders was expected to be between 50 and 100 persons.

-

E.

Each stakeholder was presented the list of stakeholders (i.e. the list mentioned in ‘D’) and was asked to choose the persons they believed were important. They could select between the names on the list, and they could also supply names they believed were missing.

-

F.

Based on the stakeholder connections found in step E, the Danish team refined the network of stakeholders to those individuals who were identified as having impact on changes in assessment practices. This final network was analysed in detail by the Danish team in collaboration with each ASSIST-ME partner to select key stakeholders relevant for inviting to the National Stakeholder Panels.

The next phase was to recruit the members from the refined list of stakeholders (determined in F). This was very much a question of finding the right balance between choosing the most influential individuals who, at the same time, would find the membership of a NSP important enough to give priority to attend the meetings. Some potential members were contacted personally. The final list of selected stakeholders was mailed to all on the list, so they could see the optimal composition of the NSP.

The resulting composition of the NSPs varied from country to country, depending on country size, the status of the researchers and the national policy culture (Bruun et al. 2015). All the researcher teams had high-profile researchers. In small countries like Denmark, it was easier to get access to relevant key persons, whereas in larger countries or in countries with a decentralised administration, it seemed more difficult to find policy-makers willing to represent a sector. In large, centralised countries, it was possible to pinpoint key persons and to have them accept membership in the NSP.

Once this NSP network was established, it was essential to deliver concrete and relevant input to them in order to keep the enthusiasm and interest alive. If not, members only attended meetings irregularly or they substituted their own attendance a less influential person from the organisation.

How Did the NSPs Work? Agendas, Successes and Problems

At the beginning of the project, the Danish partner published National Stakeholder Panel Guidelines for the NSP meetings beginning in month 12 of ASSIST-ME to provide goals and suggestions for the first meeting. The guidelines were one of the planned outputs (‘deliverables’) of the project. The NSPs were expected to have face-to-face work meetings three times during the project:

-

Early December 2013 (Month 12)

-

March 2015 (Month 27)

-

January 2016 (Month 36)

The Danish group sent out draft agendas before every NSP meeting. The agenda reflected the current project needs for members’ input and guidance and asked for their reflections on the problems currently dealt with that could contribute to answering our research questions. Each partner could supplement the common agenda with local issues, and the partner was responsible for taking minutes of the meeting and sending them (in English) to the Danish group, which was responsible for this part of the project, and uploading them on the common communication platform. The outcome of the NSP meetings will be presented in the next section in a thematic form.

First NSP Meeting (Month 12)

The first meeting settled the role of the NSP. It outlined the project research question and the problems that the researchers wanted to address. Members were asked to consider how the project could be managed for co-ownership. The following questions were asked:

How could you secure a meaningful communication between researchers, teachers and stakeholders, including policy-makers?

How could relevant stakeholders be invited to take co-ownership of the research results and how could a partnership between researchers, policy-makers and teachers be established in order to secure relevant actions following implementation guidelines?

Second NSP Meeting (Month 27)

The second meeting addressed the assessment issues at the focus of ASSIST-ME: It posed the following questions:

-

1.

Do you see any reason to change the assessment/examination culture in your country?

-

2.

If not – why not? If yes – why, and in which way?

-

3.

What will be the best strategy for changing the assessments in a direction that takes the ASSIST-ME results into consideration?

-

4.

In which ways can you – as a NSP – help the changing process?

-

5.

If we should apply for a successor, a follow-up for ASSIST-ME, which research questions should we then pursue?

Third NSP Meeting (Month 36)

The third and last meeting was held after the final implementation round. In this meeting, the common questions, arising from the previous meetings, were discussed in the light of the preliminary findings. The questions were discussed at an ASSIST-ME Management Board meeting, and the following list was agreed upon:

-

1.

What position/role describes you best?

-

2.

From your perspective, describe how students’ learning is assessed in your country. Please describe both formative assessment for learning (e.g. teachers’ feedback to students in the daily teaching) and summative assessment of learning (e.g. exams). Please indicate if these practices differ across educational levels from grade 1 to 12 (baccalaureate).

-

3.

Is learning about formative and summative assessment an important aspect of teacher education and teacher professional development TPD?

-

4.

Is it desirable to try to combine formative and summative assessment?

-

5.

Are there any nationwide (or regional-wide) high-stakes assessments in your country?

If yes: At which level(s)?

-

6.

Do you see any reason to change the assessment/examination culture in your country?

-

7.

What changes, if any, do you find necessary in the examinations at different levels to make it reflect the competence goals (both subject specific and generic) in the curriculum?

-

8.

Do you have any influence on the change of the assessment system in your country?

-

9.

If so, will you use your influence in any change process – and in what direction? How can you best change the assessments/examinations in the desired direction?

NSP Discussions

The following is a summary of some of the discussions that took place in the national NSPs. Common agreements are discussed first, and then specific country points of view are provided.

Learning About Formative and Summative Assessment in Teacher Education and Teacher Professional Development (TPD)

All panels agreed that assessment is an important aspect of teacher education and TPD. There was substantial agreement that the weight assigned to formative assessment in teacher education in TPD programmes is contingent on conceptualising the assessment of inquiry and process competences. The panels identified a range of needs that informed the project:

-

Instruments, tools, guidelines and examples of good assessment practice. However, it is not sufficient to provide teachers with diagnostic instruments – they also have to understand the underlying principles of these instruments.

-

Teachers need to be convinced that they can handle competence-oriented formative assessment.

-

Teachers need clear competence descriptions that can be used as a basis for formative assessment.

-

Regarding in-service teachers, there is a need for teaching innovation projects that integrate teaching institutions (e.g. schools) and education research groups.

It was also stressed that it is not sufficient to provide teachers with materials and discuss these in short (e.g. one day) TPD activities. The implementation has to be accompanied in practice by long-term TPD. This is in accordance with the vast amount of TPD research that indicates that one-shot workshops do not work (Goldenberg and Gallimore 1991; Lieberman and Pointer Mace 2008; Scott 2010).

The Desirability of Combining Formative and Summative Assessment

The NSPs reported a number of ways in which summative and formative assessment are combined in practice, for example, students’ work on projects is assessed formatively during lessons and is assessed summatively at the end of the course (the summative assessment is then provided as oral or written feedback). Alternatively, several summative tests can be used during a teaching unit/course and serve formative functions. However, it was generally agreed that consistency is important and there needs to be an alignment between teaching and assessment, whether it is for formative or summative purposes, there needs to be the same visible criteria. In terms of alignment of formative and summative assessment, it was mentioned in one of the panels ‘that there is lack of systematic implementation of the two types of assessment. Hence, combining the two types becomes an ever more difficult task’.

Throughout the discussion, it emerged that at some points, and for some purposes, assessment can (and should) only be formative. It is important to consider that formative and summative assessment serve different functions. In one of the panels, it was argued that the only way to combine formative and summative assessment is by evaluating student portfolios to monitor students’ learning progress.

Do You See Any Reason to Change the Assessment/Examination Culture in Your Country?

There was a strong feeling among all groups that changes in assessment culture should be adapted to the relevant contexts – not just in terms of national or cultural context but also educational level, subject, etc. All countries highlighted areas needing some kind of attention or change, but it was also stressed that assessment is a sensitive topic and, as such, quick fixes should be avoided.

In this section, we will look at points that emerged from the NSPs which are not common across countries and which reflect particular cultural or systemic issues.

There was a discussion among some panels about how the focus on formative assessment should not detract from the role of summative assessment, especially since parents are used to, and expect summative assessment:

-

‘We are not in the stage where the formative assessment could be part of everyday teaching. There is still prevailing demand for grading – the teachers need them to make final certificate and parents are used to work with them too’. (Czech minutes)

-

‘Also, regarding marking, there’s a long history in France concerning this tradition of marking that is not easy to change. One participant mentioned that the society is quite competitive and we should educate students about it as well’. (French minutes)

-

‘The panel speaks clearly in favour of a strict separation of formative and summative assessment to avoid a confusion of learning and achievement situations. In addition, it stresses that summative assessment cannot (and should not) be completely abolished’. (German minutes)

-

‘Also, many parents still advocate summative testing (grades)’. (Finnish minutes)

-

‘Stronger involvement of parents: the parents want formative assessment on the one hand, but at the other hand also want to know the “worth of any artefact” (summative assessment)’. (Swiss minutes)

There was a general consensus across the partner nations that something needs to be changed in the assessment culture to enhance the status of formative assessment, albeit there were different opinions about what should be changed and how this could be done:

-

‘The reason for the change: The school assessment doesn’t support quality of students’ learning with respect to understanding of content. The assessment should help student to “learn with understanding” and achieve better understanding of the content’. (Czech minutes)

-

‘Even if teachers often will promote formative assessment, the overall discourse in the school system is on summative assessment. The focus on figures in the school has exploded and students have high attention on their marks. More formative assessment could be a useful reflection tool for students’. (Danish minutes)

-

‘In general the NSP indicated that, on one hand, there’s a need to engage teachers in an attitude that foster more assessments for learning. On the other hand, they indicated that the (official) educational system position is quite heterogenic regarding assessment’. (French minutes)

-

‘The panel feels that there had been an assessment culture at schools once but it has gotten lost to a huge extent. If it would be possible to reimplement it, this would have positive influence on school development, teaching and learning. In this context, the school leaders are crucial’. (German minutes)

-

‘Large-scale assessments with innovative assessment formats could initiate more innovative teaching in the classrooms (positive teaching to the tests). So far, the existing regional-wide assessments are rather traditional. So one could also fear that more such tests kill innovative and creative teaching’. (Swiss minutes)

-

‘… the majority of existing diagnostic tests are devoted to measuring students’ content knowledge, without placing any emphasis to on their attitudes and or skills. In addition, it would be more productive to base students’ assessment on a wide variety of tools and methods, such as portfolio, individual and cooperative work’. (Cypriot minutes)

-

‘More emphasis should be put on feedback and focus more on learning (what is learnt instead of what is not learnt). Generally, people should be more aware about the diversity of assessment methods and practices’. (Finnish minutes)

What Changes, If Any, Do You Find Necessary in the Examinations at Different Levels to Make Them Reflect the Competence Goals (Both Subject Specific and Generic) in the Curriculum?

The role and the validity of the examinations were central issues for most NSPs, and across countries, there was an awareness that changes were needed:

-

‘The panel admits that changes in the final examinations do have a steering influence. Changes in final examinations thus always have to be preceded by changes in instruction. The examination tasks should then be changed carefully, for example, by introducing tasks that cover the concepts introduced by the educational standards. Science is part of the final examinations almost exclusively in the ‘Abitur’. Here, these new tasks could be related to experimental methods, modelling or scientific ways of thinking’. (German minutes)

-

‘Assessment could be more diverse than it is nowadays, is the impression. It should be based on diverse evidence of learning. The new core curriculum emphasizes more competences than previous one, so assessment must chance as well’. (Finnish minutes)

-

‘There is a need to engage students in assessment in a way that focuses on assessment for learning. Students work in a different way with peers than with the teacher. There is a need to change the assessment culture so that the way in which students work with the teacher resembles the way they work with peers. Teachers need to change their teaching practices to integrate formative assessment’.… ‘there is [however] a tradition for summative assessment and grading, which is not easy to change. The French NSP suggests collaborations with teaching institutions and research collaborative groups in establishing teaching innovation projects’. (French minutes)

-

‘There is a need to change the assessment culture because the used assessment strengthens only the external motivation […] students and teachers don’t think enough about the learning goals, characteristics of quality performance and products [and since] the school assessment doesn’t support quality of students’ learning with respect to understanding of content … teachers are mainly focused on the fact whether the students have learnt the topic or not […] teachers don’t discuss the mistakes with students very often. However, there is still a demand for grades, the teacher needs them to make final certificates, and parents are used to work with them too’. (Czech minutes)

What Will Be the Best Strategy for Changing the Assessments in a Direction That Takes the ASSIST-ME Results into Consideration? And in Which Ways Can You, as a NSP, Help the Changing Process?

-

‘Examples of tasks with the described competencies as well as guidance for assessment and examples of students’ work. These materials will help future teachers and in-practice teachers with formative assessment. In addition, there is a need to expand the understanding of school assessment (…) as it should not be seen only as a tool, but also as an (educational) goal (…) we could use some results from this project to promote this change’. (Czech minutes)

-

‘You need to combine initiatives on a local level with centrally decided changes in the examination system. Start experiments with no-marking classes (within the given regulations), increased emphasis on formative assessment etc, and evaluate the results. At the same time design new examination forms and concrete strategies for assessment, research on the implementation and present the results for the Ministry of Education’. (Danish minutes)

-

‘There is a call for integrating formative assessment into pre-service teacher training. Another strategy is to generate projects by the local institutions that integrate formative assessment practices in their projects’. (…) All the NSP members support actively the French ASSIST-ME Conference in Grenoble in October 2016. They will take part in some panel discussions during the conference. Each NSP member can help the changing process in its own level:

Research associations (ARDIST, ARDM) can help for dissemination and the sharing of research results (theoretical and experimental) within the research network that include a lot of teacher educators. They can also share results with teachers’ associations in order to reach teachers.

The DEGESCO (General Direction of School) can present information on the national site EDUSCOL (An official site for school educators and teachers that aim at informing and supporting teachers). DEGESCO can also pass information onto National Education school inspectors.

National Education school inspectors can support our action in the National Plan of Formation for in-service teachers’ professional development. They said that we need to invest in pre-service teacher’s education. Collaborative research groups (in-service teachers, teacher educators and researchers) can develop specific training actions about formative assessment in in-service teachers’ training’. (French minutes)

Summing Up the NSP Discussions and Work

All NSPs had very engaged discussions, reflecting the importance that all stakeholder representatives attributed to assessment. Despite quite different foci and nuances, as illustrated by the excerpts above, it was possible to extract some common agreements and recommendations which will be outlined in the following ‘general recommendations’ section.

On reflection on the importance of having a forum for dialogue across political interests and power relations in order to establish mutual trust and understanding, it was clear that the NSP constituted a free space for exchange of ideas and points of view. It was also clear that many controversial questions were openly discussed. The discussions often revolved around the accountability purposes of assessment versus the learning purposes and the potential contradictions between the two purposes.

Laveault (2015) refers to two accountability orientations proposed by Blackmore (1988):

-

Policy targeted at improving the management of the school system: Economic-Bureaucratic Accountability (EBA)

-

Policy targeted at improving students’ learning: Ethical-Professional Accountability (EPA).

An EBA orientation will increase students’ performance and achievement levels through enhanced efficiency in the use of human and material resources. ‘Teachers are directly held responsible for students’ achievement results and therefore, should use AfL [Assessment for Learning] to improve them. Hence, in such a context, “The results are what matters, and the processes are validated only by performance” (Jaafar and Anderson 2007, p. 211)’ (Laveault (2015), p. 23f). This approach has as the only purpose a clear accountability use. An EPA orientation will be based on a shared responsibility, and ‘Emphasis is put on teachers working together as a professional learning community and on students’ improved learning skills and sustained achievement levels (Jaafar and Anderson 2007)’ (Laveault 2015, p. 23f). This approach attempts to combine a learning purpose with an accountability policy. A more expanded discussion of the problems involved in such an approach can be found in Chap. 3.

The tension between these two orientations was clearly articulated in the NSPs, and it became clear to all stakeholder representatives that a solution was necessary and that it could only be developed through strengthening the cooperation between teachers, researchers and key stakeholders, especially from official bodies like the Ministries of Education.

General Recommendations

The ASSIST-ME Lyon meeting in February 2016 had as a main theme the summing up the findings and formulating the project’s general recommendations, which was reported to the EU as Deliverable D7.3. All partners brought with them the minutes from the NSPs and also minutes from the last meeting in their LWGs where teachers had discussed questions very much in line with the questions for the third NSP meeting.

Thematic groups were formed with members from all partner institutions. The groups wrote down statements everyone could agree upon based on the different national statements and conclusions. These statements were then edited together into five broad recommendations for policy-makers and other key stakeholders on how formative assessment of inquiry-based teaching and learning might be done more effectively across a range of countries. This process builds on the trial implementation of the four ASSIST-ME assessment methods (i.e. marking (grading and written comments), self and peer feedback, on the fly interaction and structured assessment dialogue) and recommends how these approaches can be strengthened and how existing assessment systems might be modified to enable formative assessment to function effectively in STM classrooms. Many of the recommendations are neither new nor ground breaking to a researcher in the field of STM education, but they have been carefully discussed among stakeholders from the partner countries involved in educational issues, and for many policy-makers they constituted rather strong statements.

Recommendation 1: A Competence-Oriented, Inquiry-Based Pedagogy Is Important

An inquiry-based teaching and learning approach helps young people develop critical thinking and scientific reasoning that are important in creating citizens who can make sense of the world they live in and make informed decisions. Inquiry-based teaching and learning has proved its efficacy at both primary and secondary levels in increasing interest and attainments levels in STM subjects, while at the same time stimulating teacher motivation. The ASSIST-ME project confirms this understanding and goes further, in defining and operationalising key competencies within STM subjects that help students utilise and develop scientific knowledge and processes.

The project points at ways to implement such a competence approach in different educational cultures and recommends adjusting educational policies to make this possible.

Recommendation 2: Focus on Formative Assessment to Support Competence-Based Inquiry Learning

Formative assessment provides both the time-frames and opportunities to look at how students develop competencies. ASSIST-ME has collected solid evidence of the huge learning potential of formative assessment methods via student goal orientation, making the learning journey visible and explicit. It has also supported teachers to identify the best next steps in student learning. However, the project has also revealed that formative assessment is not an integrated part of current STM teaching and that, for many teachers and students, it is difficult to implement in a structured form.

-

It is therefore necessary to promote a teaching approach integrating formative assessment into the classroom culture and to frame the educational condition, resources and the curriculum to make it happen.

Recommendation 3: Reduce the Emphasis on Summative Assessment to Give Room for Formative Assessment

ASSIST-ME found that the summative assessment load needs to be reduced to allow teachers time to focus more on formative aspects, on assessment for learning, and to highlight and emphasise those aspects of learning that we value within the STM community. Curricular material, textbooks and resources need to include specific and detailed reference to their formative potential and to their use in the classroom so that both teachers and students are focused on how assessment can support learning.

-

It is recommended to develop national assessment policies that recognise the different purposes and potential involved in the interactions between formative and summative assessment and that makes it possible to realise the full potential of formative assessment processes.

Recommendation 4: Develop New Forms of Examination Able to Capture STM Competencies

The ASSIST-ME implementations have made it clear that a big gap exists in many countries, between the examinations at the end of a course and the learning processes during the course. While the teaching-learning processes are aiming at developing the learners’ STM competences, the examinations often fail to assess these properly. To bridge this gap, summative assessments should be more in alignment with the formative processes in everyday teaching and should be designed to assess the STM competences in a valid and reliable way. There is evidence from the project that classroom practice is heavily influenced by the well-recognised backwash from summative examinations. The development of examination forms that assess a broader range of STM competences will have a positive impact on the teaching of these competencies.

-

It is necessary to develop new types of examination that are able to capture the central STM competencies and also be aligned to the formative approaches in the classroom.

Recommendation 5: Teachers Need Support in Implementing and Enacting Classroom Assessment of STM Competencies

ASSIST-ME has developed formative assessment tools able to support teachers in defining and articulating appropriate feedback comments for students, thereby strengthening the assessment literacy of both teachers and students. Assessment tools alone are insufficient, though, teachers need to adapt the tools to the educational contexts that exist in the local environment. This requires support from peers and educators in translating tools for specific contexts. The ASSIST-ME model may provide an effective format for these programmes: three meetings per year, involving a team of teachers and researchers or teacher educators in designing and testing new teaching units in an iterative process dedicated to the ongoing improvement of the inquiry activities and their assessment tools.

-

ASSIST-ME has identified a strong need for professional development programmes (pre-service, induction and in-service) that support teacher understanding of formative assessment and inquiry-based teaching and learning and facilitate the implementation and enactment of formative assessment processes in STM classrooms at both primary and secondary level.

The Impact from ASSIST-ME on Education and Educational Policy

It is difficult to measure the long-term impact of an educational research project such as ASSIST-ME. Education is a complex interplay between the teachers in the classroom and school leaders; both framed and conditioned by educational policy. Research can influence how some teachers teach their classes and how some school leaders support and promote new teaching approaches – within the given frame. It can also affect the policy system to change the conditions for teaching, thus from a top-down position steer or support teachers’ work. The ASSIST-ME project intended to do both.

Through the work in the LWGs teachers have been supported in changing their assessment practice. They have been introduced to various assessment methods and their implementation in the classroom as described in Chaps. 4, 5, 6 and 7. This work has been disseminated through national channels such as national conferences, teacher journals, teacher networks, in-service teacher training, etc.

The national policy level has been influenced in various ways from country to country.

In Denmark, a new Act for upper secondary education was passed through the parliament in 2016 with the intention of implementing new assessment forms and formats inspired by ASSIST-ME. An in-service programme for teachers and school leaders focusing on increasing student feedback is running in the spring 2017 with participation of ASSIST-ME researchers. The Danish Ministry of Education is launching a school experiment programme allowing schools to minimise summative assessments and to put more emphasis on formative assessments. A new Danish strategy for science education K-12 is formulated during spring 2017 – and ASSIST-ME knowledge is used and influencing the strategic goals and the initiatives adopted to realise the goals.

Each ASSIST-ME partner has their own story about influence, depending on the relations they have been able to establish to policy-makers. But besides these direct effects on policy, the project has had impact on the research field associated with formative assessment through documentation of features that seem to enhance or impede the enactment of the assessment methods.

A Wider European Perspective

To put ASSIST-ME in a wider European perspective, this section will review some of the different projects that sought to influence educational policy in Europe. The first is the ‘mother’ of all the inquiry-based science education projects within EUs Seventh Framework Programme in Science in Society. The programme rolled out in 2016, and ASSIST-ME was one of the last funded projects in this initiative. The following three country-specific cases are discussed in the next section: The Norwegian assessment for learning project illustrates a strong state controlled TPD programme, the New Standards and Curricula in Switzerland is an example of a curriculum project in alignment with many of the ideas in ASSIST-ME, and, finally, the English case incorporates reflections on the impact – or lack of impact – of a well-known science education policy initiative.

The cases together with the ASSIST-ME experiences provide a background for the perspectives of the chapter.

The Rocard Report

The publication Science Education Now: A renewed pedagogy for the future of Europe (European Commission 2007) – the so-called Rocard report – is an example of how science education policy was formed within the EU’s Seventh Framework Programme in Science in Society. In response to a report from the OECD in 2006 (Evolution of Student Interest in Science and Technology Studies – Policy Report; Global Science Forum), a high level expert group on science education was formed to make recommendations based on a review of projects that seemed to be having a positive impact on recruitment to the sciences, and the report identified the necessary preconditions for increased implementation throughout Europe. The estimated level of support within the Science and Society (SIS) programme at that time was estimated to be 60 million euros over a 6-year period. The leader of this committee was Michel Rocard who was a member of the European Parliament and former Prime Minister of France. The other five members were leading scientists in Europe with only one science educator, Doris Jorde, on the committee. Policy was made by looking at existing documentation on what was working in science education, particularly with inquiry-based science teaching (IBST), as well as the identification of successful projects (wherein Sinus plus and Pollen were recognised as good examples for scaling-up). Michel Rocard gave the committee the authority required to prioritise science education within the EU.

What followed was the release of project funding to IBST projects involving science educators and informal science learning environments throughout Europe. The number of projects, number of participants from every country in Europe and number of ideas for promoting IBST are daunting in retrospect. An overview of the projects can be seen at www.scientix.eu.

A Norwegian Case

The Norwegian National Curriculum (2006) is written in the form of competency goals for all subjects in grades 1–13 (1–7, 8–10, 11–13). Competency goals in the integrated science subject (naturfag) occur in grades 2, 4, 7, 10 and 11. Biology, Chemistry, Physics, and Earth Science have competency goals for grades 12 and 13. National exams are administered after grade 10 (pupils may be selected for an oral examination) and at the end of grade 13 (students may be chosen for either oral or written examination). All children have the ‘right’ to formative evaluation in all subjects according to the national rules and regulations governing schools.

Based on the information above, one could say that Norway has very little testing compared to many other countries. Norway participates in TIMSS and PISA, but these tests are designed to identify trends at the national level. The Department of Education places trust in local school evaluation, supporting these efforts through national programmes for TPD in evaluation and the development of web pages (http://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/vurdering). These help explain and provide tools for evaluation (both formative and summative).

In 2010, the Department of Education launched a national TPD programme in ‘Vurdering for læring’ (assessment for learning) to improve school practice and thereby improve student learning outcomes. As of 2016, seven groups of teachers (representing over 300 municipalities) have participated in the programme in which schools build up communities of practice. Four principles guide the TPD programme.

Students learn best when they:

1. Understand what they are to learn and what is expected of them

2. Receive information on the quality of their work

3. Receive information on how to improve their work

4. Are involved in their own learning processes (through evaluation of own work and evaluation of progress)

The focus of the professional development programme is to move thinking away from concentrating on the learning activities students are doing to a focus on what students are learning.

As entire schools participate in these programmes, it is important to ask if the information is improving the way science teachers work in their own classrooms with assessment. Are the ideas presented above applicable for the practices employed in teaching science?

Do we know how to assess student progression in science lessons? Do we have a good ‘tool box’ in science for helping teacher to make student thinking visible?

Perhaps what is more important for us to think about when working with general ideas of assessment in schools is whether we, as science educators, have taken this type of pedagogical language into our own way of thinking about assessment in science classrooms. In science TPD and pre-service teacher education programmes, science educators often use their own language of assessment ideas and language, not necessarily corresponding with the literature presented in the ‘assessment for learning’ national TPD programmes.

Combining the four points above with how we work with science teachers (pre-service and in-service), the following questions are pertinent:

Conducting laboratory exercises is common in science lessons. When science teachers decide that students will conduct a lab: Are students clear about why they are doing the lab? Do teachers let students know what will be expected of them? Are clear goals for the lab articulated to students before they begin, rather than simply providing recipes for a procedure? Are students allowed to engage in the process of designing the lab?

Do teachers let students know how the lab will be assessed? Is it only the final lab report that is important or is the entire process of doing the lab also assessed? If the whole process is important, how will it be documented? Are students given the opportunity to discuss their results with others? Are students given the opportunity to use modern technology when collecting data in the lab (smart phones for example? and in their laboratory reports?

Are students given feedback on their lab reports? Are students given the opportunity to wonder about outcomes from the lab, including alternative interpretations? Are students asked to place the lab into an historical context or perhaps wonder about the importance of the outcomes in a modern science perspective?

The assessment for learning project in the Norwegian curriculum places a focus on what students are learning, not just on what students are doing. In science lessons, it is easy for science teachers to see activity and assume that learning is happening. However, it is not until we look for evidence of learning, through formative assessment tools, that we improve student outcomes.

New Standards and Curricula in Switzerland: A Focus on Inquiry-Based Learning and Assessment

In the last 15 years, Switzerland has begun to implement new standards and curricula which will lead to substantial changes in the Swiss educational system. In science, inquiry-based learning and formative and summative assessment play an important role in both standards and curricula.

National Standards

Triggered by PISA results, the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Education (EDK 2011; Labudde 2007; Labudde et al. 2012) initiated the project HarmoS (Harmonisierung obligatorische Schule Schweiz: Harmonisation of the Compulsory School Switzerland). Switzerland has a federal political system, that is, each of the 26 cantons has its own educational system. The mobility of the population demands for more harmonisation in education. HarmoS intends to establish comprehensive competency levels and standards in specific core areas for compulsory schools in Switzerland including science. The standards are defined for the end of grades 2, 6 and 9, that is, they are based on a progression model. The national standards in science include six skills: (1) asking questions and investigating; (2) exploiting information sources; (3) organising, structuring and modelling; (4) assessing and judging; (5) developing and realising; and (6) communicating and exchanging views. As an overall skill ‘working self-reliantly and reflecting on one’s own work’ is added. Each of the skills – and their subskills – has been described meticulously and with a degree of sophistication. Many of them are related to inquiry-based learning. The following examples belong to the skill ‘asking questions and investigating’: (a) at the end of grade 6, that is, 12-year-old students, and (b) at the end of grade 9, i.e. 15-year-old students:

-

(a)

Grade 6: ‘Students can perceive simple situations and phenomenon with different senses; they can observe and describe them. In regard to the situations and phenomenon, they are able to ask questions and formulate problems. Guided by the teacher, students can perform investigations and experiments; they can carry out estimations and measurements, collect and interpret data’.

-

(b)

Grade 9: ‘Students can perceive situations and phenomenon with different senses; they can observe and describe them. In regard to the situations and phenomenon, they are able to ask different questions and to formulate problems and simple hypotheses, and to determine variables in order to check them. They can plan and perform investigations and experiments. Doing so, they are able to carry out specific estimations and experiments, to collect and interpret data, and to answer their questions and to give their view on the hypotheses’.

Curriculum 21

The national standards and competences, as defined by HarmoS, were the frame for the development of the new curricula, one for each of the three linguistic regions of Switzerland, that is, German, French and Italian. For the German speaking part of Switzerland, that is, 21 cantons out of 26 cantons, the curriculum was named ‘Curriculum 21’ (Lehrplan 21). The subjects ‘Nature-People-Society’ (grades K-6, i.e. age 4–12) and ‘Nature and Technology’ (grades 7–9, i.e. age 12–15) focus on both inquiry-based learning and formative assessment.

-

The curriculum defines hundreds of so-called competences; dozens of them are related to inquiry-based learning. For example: ‘Students can investigate, reflect, and present information about nature and technology on their own. […] Students can plan, implement and interpret investigations in regard of the interaction of plants and soils’ (D-EDK 2014a, NT 1.3NT 9.3c).

-

The so-called basics of Curriculum 21 describe formative and summative assessment: ‘Formative assessment: During the lessons, the students receive encouraging and constructive feedback, which they can use developing competences and which supports their learning process. This feedback is adapted to the individual learner, it integrates aspects of self-assessment. […] Summative assessment focuses on the actual performance level of students. Primarily, it is based on the objectives of the curriculum […]’ (D-EDK 2014b, p. 9–10).

The quotes are paradigmatic examples showing how inquiry-based learning and formative assessment as two different instructional strategies are integrated in Curriculum 21. Both have already played an important role in previous curricula, but they are enforced by the new curriculum which will be implemented gradually in the next few years. Each canton has its own schedule for the implementation; the first two cantons already started in August 2015 and the last ones will start in 2020.

Teacher Training Programmes and Continuous Professional Development (CPD)

Teacher training colleges and institutions of CPD play an important role in the cantonal educational systems; CPD is well developed and well recognised by teachers and other stakeholders. For more than 20 years, these institutions offer modules and courses that promote Inquiry Based Learning (IBL). However formative assessment has seldom been an explicit part of programmes or CPD. This situation will change, though; with the implementation of Curriculum 21, there will be large programmes of CPD in all cantons. Teachers should learn about the objectives and content of the new curriculum. In science, a main emphasis will be on both IBL and formative assessment. The same is true for teacher training programmes across Switzerland.

Politics and Administration

In general, both politicians and administrators support the ideas of IBL and formative assessment. In a small country like Switzerland, with a population of only 8 million people, there are many relationships between cantonal ministries of education, teacher training colleges, teacher unions and associations and teachers. Therefore, a new development or a new concept that is well accepted by different kinds of stakeholders, like the concept of IBL, will also be accepted by other stakeholders. In addition to formative assessment, the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers is implementing national monitoring that includes nationwide tests in the main subjects, that is, mathematics, first and second language, and science. The monitoring will be based on a representative sample; it should yield results with regard to the implementation of standards and curricula: Which competence levels do the students achieve by the end of grades 2, 6 and 9? This monitoring is a form of low-stakes assessment. Furthermore and in contrast to the national monitoring, some cantons are planning and implementing high-stakes assessments at the end of grade 6 and 9. The results of these assessments will be part of the final certificate that the students get at the end of primary and secondary school.

The Role of ASSIST-ME

The project ASSIST-ME only started in 2013, that is, it could not have had an influence on the established national standards and only a marginal influence on Curriculum 2014. However, it has had and will continue to have effects on the implementation of the new curriculum, on teacher programmes and CPD and on formative and summative assessment. The Centre for Science and Technology Education (CSTE), which is the Swiss partner in ASSIST-ME, and its members are responsible – in most cases together with other institutions – for the following activities and projects:

-

1.

Educating pre-service teachers at our university as well as being engaged in CPD, for example, in the big programme SWiSE (2017, Swiss Science Education, customers: Teachers, ministries of education, universities, and foundations; since 2011).

-

2.

Planning and developing checks in science for the end of grade 8 and 9; IBL and experiments play an important role in these checks (customers: ministries of education of the four cantons of Northwestern Switzerland; annually since 2014).

-

3.

Organisation of a 1-day conference on formative and summative assessment in science for cantonal ministries (about 30 specialists of cantonal ministries; November 15, 2016).

-

4.

Part of the advisory board for the national monitoring (customer: Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers, since 2016).

-

5.

Writing science school books for grades 7–9 with an emphasis on IBL and with hints for formative and summative assessment in the teacher edition (customer: a Swiss publishing company; 2014–2020).

-

6.

Helping to implement Curriculum 21, in particular the ideas of IBL and formative assessment.

These activities and projects show that ASSIST-ME has had and will continue to have an impact in Switzerland. Thus, there are a lot of synergistic effects between the European project and several Swiss projects.

An English Case

Over a decade ago the Nuffield Foundation sponsored two seminars which resulted in a report entitled ‘Science Education in Europe: Critical Reflections’ (Osborne and Dillon 2008). Although the majority of the attendees were science education researchers, there were a scientist and a policy-maker from the EU at each seminar. The overall approach was inspired by the series of Nuffield Foundation seminars that led to the seminal UK science education report, Beyond 2000 (Millar and Osborne 1998), which has been cited (according to Google Scholar) almost 1500 times.

‘Science Education in Europe’ examined three aspects of science learning: curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. The report was highly critical of many aspects of the then current policy and practice. In terms of assessment, the report’s authors concluded that:

For too long, assessment has received minimal attention. Tests are dominated by questions that require recall – a relatively undemanding cognitive task and, in addition, often having limited validity and reliability. Yet, in many countries, the results of a range of tests, both national and international, are regarded as valid and reliable measures of the effectiveness of school science education. Teachers naturally, therefore, teach to the test, restricting and fragmenting the content and using a limited pedagogy. (Osborne and Dillon 2008, p. 9)

Those comments still hold true today in many, if not all, of the ASSIST-ME partner countries. The report went on to identify a possible course of action:

Transforming this situation requires the development of assessment items that are more challenging; cover a wider range of skills and competencies; and make use of a greater variety of approaches – in particular, diagnostic and formative assessment. (p.9)

A number of individuals and institutions have done just that although implementing new assessment strategies across educational systems has proved problematic.

The report made a number of recommendations including:

EU governments should invest significantly in research and development in assessment in science education. The aim should be to develop items and methods that assess the skills, knowledge and competencies expected of a scientifically literate citizen. (p.9)

The EU did invest in research and development in assessment in science education but how far have we come and where are we going? If anything, the dominance of large-scale international testing such as PISA has grown over the last decade. While some have argued that such comparisons have been used to lever up standards in a number of countries, others argue that such tests distort policy and thus classroom practice.

Reflecting on the impact of ‘Science Education in Europe’ one could argue that while the European Commission was sympathetic to its messages, systemic change has foundered on the way that politicians interpret the results of the OECD PISA assessments together with a natural inertia in education systems to any radical change in student assessment.

Nowhere in the world is student assessment as much of a political football as in England. With its long history of practical work in school science and its concern for science for all, one might expect that England might have the answers to many of the questions that drove the ASSIST-ME project. The pioneering work of Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam is well known to anyone interested in formative assessment, and it was a starting point for many of the ASSIST-ME developments. But how far has England come?

In February 2017, the Wellcome Trust in collaboration with the Gatsby Charitable Foundation announced a new scheme which focused on ‘Assessing Practical Science Skills in Schools and Colleges’. The scheme ‘supports researchers who want to explore the best ways to assess students’ practical science skills’. Funding would be made available to support researchers who wanted to address ‘the challenge of assessing students’ practical science skills in a way that is valid, reliable and feasible. Rather oddly Wellcome added ‘We might also consider other ideas that don’t meet these criteria, but develop new ways to assess students’ practical science skills’. There does seem to be an element of wheel reinvention here. Surely in 2017 enough is known about how to assess students’ practical skills in science? Should not the priority be transforming science education as the Nuffield report recommended through ‘making use of a greater variety of approaches – in particular, diagnostic and formative assessment’ (Osborne and Dillon 2008, p. 9).

Discussion of science education policy in England tends to be dominated by the learned societies and by the Association for Science Education, the leading professional organisation for those involved with the teaching of science. Despite the many working parties, committees and conferences that have been devoted to assessment in science in England, the level of thinking does not seem that advanced. Furthermore, the impact that these discussions, pontifications and reports have on policy-makers seems limited. Some measure of where the debate is now in England is indicated by this quote from SCORE – the Science Community Representing Education.

Assessment largely determines what students are taught, and has an enormous influence on the style and emphasis of teaching and learning. Therefore, it is essential that awarding organisations, Ofqual and the Department for Education work together across organisations, and with others, to ensure that an effective, evidence-based mechanism for assessing practical work is developed alongside content. (SCORE n.d.)

It might be ‘essential’ that the Department for Education works with other organisations but the mechanism for making this happen is not clear. All too often in science education in England, the rhetoric and the reality are far apart.

Conclusions and Perspectives

So, what can we conclude? The science education research community seems to have accepted that changing classroom assessment practices towards more emphasis on formative processes is a key dimension of raising attainment in school science. But the dominating political power still favours the summative elements.

The ASSIST-ME project has demonstrated that bringing researchers and teachers and policy-makers in close dialogue about concrete issues regarding assessment gives an enhanced awareness and understanding of the role of formative and summative use of assessment. This has influenced the attitude of the individual policy-maker and given him or her a more nuanced view on problems related to assessment and an informed openness for debating solutions.

It is also evident that ASSIST-ME has had influence on the educational policy in the participating countries. The extent of influence differs, of course, from country to country, and many effects will only be visible after a longer period of time. But all partners report of impact on the educational and political scene in their country. Many have arranged national conferences including policy-makers, and all partners give various examples on how their researchers have been invited to participate in curriculum development, teacher professional development workshops, expert groups on assessment, etc. Through such activities and through the NSPs, the results from ASSIST-ME have been spread and have affected the public discourse.

It has been crucial that dissemination of information and the debates in the NSPs were based on research results originated from collaboration between researchers and teachers. The research foundation gave the background for the debate a high degree of legitimacy, both among teachers and policy-makers, and thus some seriousness and credibility to the outcome. It has also been fruitful that NSP members were involved indirectly in the research process. It gave them insight into the complexity of educational research and a certain humbleness towards quick solutions.

This has not necessarily led to consensus, which is a rare thing in policy, and it has not eliminated all resistance to change. Much resistance to change has legitimate reasons seen from the point of view of the actor. Teachers have limited capacity for change if not giving the necessary supports. Professionals need time and training for professional development. Policy-makers are often restricted in their actions by the point of views they normally represent, talking on behalf of their policy or interest organisation. But the ASSIST-ME approach has pointed at some ways forward for affecting educational policy.

What needs attention in the future is whether the lack of profound changes in the assessment systems can be tracked down to inertia in the educational environment or to resistance to change among policy-makers. It is necessary to pose the question: Is the lack of change in the directions indicated by research such as ASSIST-ME due to lack of knowledge among policy-makers – or is it rooted in values among the same policy-makers opposing the research findings?

Maybe it is about time to realise the political character of educational policy issues, especially issues related to assessment. When things don’t change, it could be because strong economic and political powers don’t want them to change. Some policy actors might simply find a change in the fundamental ways the educational system is currently functioning a threat to their basic values. In this respect, change in the assessment system is a question of value clarification and value change. This approach is, perhaps, key to understanding where we go next.

References