Abstract

Subspecialty surgery, the provision of surgical care by trained subspecialists which typically requires advanced technology, materials, and infrastructure, is an emerging field on a global scale. Worldwide, there is a large burden of disease correctable by subspecialty surgery despite insufficient personnel and inadequate access to care for the majority of patients. Historically, subspecialty surgery in resource-limited settings has slowly progressed along a continuum of care. Numerous models and methods of delivery, each with notable advantages and disadvantages, have been utilized to provide care along this continuum. Based on these, providers and those they partner with can apply a model to further the provision of care. When done well, this delivery of subspecialty surgical care benefits not only the individual patient, but the community as a whole. Tenwek Hospital, a faith-based mission hospital that utilizes multiple methods of delivery, represents one example of how the continuum of the delivery of care can be used to promote cardiac surgery for individual patients while improving infrastructure and capacity to care for a community. This chapter illustrates some of the potential models available to enhance the subspecialist in global surgery.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction and Overview

The Essentials

-

Subspecialty care should be readily accessible, safe, financially feasible, and allow exchange of ideas for continued quality improvement.

-

Expanding upon essential surgery, subspecialty surgery consists of the provision of care by trained subspecialists and typically requires advanced technology, materials, and infrastructure related to the services provided.

-

The history of how subspecialty surgery has developed in resource-limited settings can contribute to an understanding of how to advance its provision.

Globally, subspecialty surgical care should be readily accessible, safe, financially feasible, and allow exchange of ideas for continued quality improvement. This ideal is not the current situation for millions of people worldwide. In low-resource settings, availability of care is sporadic, outcomes are often subpar, costs are prohibitive, and the skilled personnel and appropriate infrastructure to accomplish this task are lacking. In this chapter, we will discuss the history of subspecialty surgical care, the current models used to deliver it, and how the individual provider may fit into this continuum with the hope of advancing access and improving quality of subspecialty care to low-resource communities.

Definitions

The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery recently detailed the appalling lack of surgical care for billions of people [1]. The report focused mainly on the lack of essential surgical care, defined as “any and all procedures, contextually and culturally dependent, that are deemed by that region, society, or culture to promote individual and public health, wellbeing, and economic prosperity.” In some settings, this essential surgery is performed by those with medical degrees and further training. In other locations, it is performed by those with apprenticeships and procedural training only. Within low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) that have accredited specialists in surgery, these specialists may provide both essential surgical care and subspecialty surgical care. These divisions of labor will be further explored in the different models available for subspecialty surgery.

In most resource-limited settings, subspecialty surgical care is rarely or sporadically available. Expanding upon essential surgery, subspecialty surgical care consists of the provision of care by trained specialists and includes various subspecialty disciplines such as ophthalmology, ENT, plastic and reconstructive surgery, pediatric surgery, urology, neurosurgery, advanced laparoscopy, and cardiothoracic surgery. Typically, subspecialty care requires advanced technology, materials, and infrastructure related to the services provided. Although some straightforward subspecialty care could be provided at the district hospital level, advanced care is generally suited for a referral center serving a larger population [2, 3].

History of Subspecialty Care in Developing Countries

To better understand the way forward for global subspecialty surgery, it is imperative to understand past successes, failures, and the many factors historically that have contributed to a shortage of healthcare workers, a myriad of health disparities, and a lack of subspecialist surgical care [4]. Global surgery was perhaps founded decades ago during an era defined by highly dedicated expatriates. Funding was often supplied through the generosity of nongovernmental organizations, such as churches and charities. In these early years, expatriates dedicated their careers and lives to the cause of bringing surgical care to people without such access. For example, Peter Parker, who introduced anesthesia to China, was among the first missionary surgeons [5]. Lucille Teasdale practiced surgery in Uganda for years until finally contracting and dying from HIV/AIDS. With a higher purpose of caring for individuals and communities, missionary surgeons invested not only their careers but their lives to the cause. As mission hospitals expanded, general and subspecialty surgical care for community-identified problems also grew. Throughout this era, the surrounding communities of these hospitals were significantly impacted and enjoyed the benefits of considerable investment in infrastructure, workforce development, and provision of healthcare. But hospitals were dependent upon the missionary to stay and invest his or her life into the cause. Furthermore, the effect was localized, and national healthcare systems were rarely influenced [6].

The Alma Ata Declaration, in 1978, signaled a change in the delivery of healthcare worldwide [7]. In an inadequately supported attempt to achieve “healthcare for all,” funding was directed toward community health initiatives such as breastfeeding, oral rehydration, and immunization, while structural adjustment programs limited investment in medical personnel and infrastructure [8–10]. Although worthy goals, this resulted in disturbingly preferential investments at the great expense of surgical capacity [11]. Consequently, scores of capable, educated physicians and nurses left home for brighter futures elsewhere [12]. Some workers moved to private, urban hospitals within their own countries. Tragically, many were actively recruited by resource-rich nations to fill an increasing need for healthcare workers in those countries [13, 14], depriving LMICs of healthcare workforces and potential leaders [15–17]. In this way, the Alma Ata agreement contributed to the current health disparities, where worldwide, over five billion people lack access to surgical care which the workforce is not yet capable of delivering [1, 18].

The current era is one of increased focus on global provision of surgical care but with an unfortunate lack of focus, organization, and accountability. Globalization has increased awareness of the problem and made travel easier and more affordable. A relatively recent understanding of global surgery as a population-based, cost-effective avenue to restoring health and improving infrastructure has enabled a new-found interest in its promotion. As a result, healthcare providers from resource-rich nations have flocked to resource-poor areas, mostly with good intent, but regrettably too often with mixed results. Hundreds of short-term surgical camps have materialized [19]. In 2004, the American College of Surgeons created a database of volunteer opportunities and facilitated short-term involvement calling the campaign, “Operation Giving Back” [20]. Short-term surgical trips (STSTs) have been a significant yet unquantified source of subspecialist surgical care in resource-constrained settings. Given the abundance of STSTs and the inconsistency in accountability, it is impossible to accurately detail the impact of STSTs on subspecialty surgical care. Both global organizations and academia are beginning to understand the necessity of promoting surgical access in order to further the health and success of communities and have attempted to correct the incongruity of STSTs by establishing partnerships, cultivating educational efforts, and aspiring to longitudinal collaboration [21, 22]. National governments and Ministries of Health have occasionally recognized subspecialty care, although budgets are often constrained by other priorities. And finally, local institutions, including mission hospitals, have tried to adapt subspecialty surgical care appropriate to their settings, but this access is only sporadically available.

Current Overview of Subspecialty Surgical Care in Low-Resource Settings

The Essentials

-

Although data is sparse, evidence suggests there is a large burden of disease globally that could be correctable by subspecialty surgery.

-

Sufficient personnel for subspecialty surgical care is lacking in low-resource settings.

-

Access to subspecialty care is challenging and often limited to urban areas.

The availability of subspecialty surgical care is varied throughout the world, but in LMICs access is especially limited. Few studies exist regarding subspecialty surgical care in LMICs, and extensive data is not yet available to draw conclusions. Current qualitative research shows that there exists great potential for improvement. Outcome reports for various models and experiences are sparse (Table 5.1). The data currently available to draw conclusions may not accurately reflect the ongoing efforts of those working within low-resource settings because many hospitals and surgeons have provided subspecialty care but have never published their experiences. There are many reasons that specialist availability in LMICs is limited including the lack of infrastructure, resources, and trained personnel. Subspecialty care, where available, is often focused on a specific condition and provided by a fragmented group of outside specialists, urban academic institutions, nongovernmental organizations, faith-based hospitals, and various combinations thereof.

Need for Subspecialty Surgical Care

Attempts at quantification of the burden of surgical disease as well as its contribution to disability and premature death of a population have been of recent interest. There is a particular interest in essential and emergency surgery given its role in immediate reversal of health disparities. However, little data exist about the burden of subspecialty surgical disease. Specific surgical conditions, those which typically require subspecialty training, have been addressed in various reports of their cost-effectiveness, availability of services, occurrence of disease, and the related disability and mortality caused by the condition. For example, congenital conditions are a leading cause of pediatric mortality and morbidity. An estimated 93 million children and 7% of all births are impacted with some form of moderate or severe deformity [46, 47] which would benefit from surgical intervention. Surgically correctable conditions may significantly negatively impact quality of life. Reports exist on the burden of cataracts [48], otitis media [49], osteomyelitis [50, 51], hypospadias [52], urological conditions [53, 54], and congenital conditions such as cleft lip or palate and clubfoot [55, 56]. As a whole, subspecialty surgical care has not been as emphasized as emergency and essential care, which in of itself has not been as emphasized as many other public health priorities.

Number of Subspecialist Surgeons

Quantifying the number of surgeons serving a population is a difficult task [57]. Variations of definitions between those who perform operations, general surgeons, surgeon specialist, and surgical subspecialist prevent a complete understanding of the number. Furthermore, surveys of Ministries of Health may not capture the substantial contributions of NGOs and faith-based hospitals. As an example, in southwestern Uganda, a survey of hospitals revealed 43 consultant specialist surgeons (0.7 accredited surgeons per 100,000 population) including all of the specialties of general surgery, obstetrics, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, dental surgery, neurosurgery, ENT, and urology. The survey, which reviewed mandatory logbooks maintained at each of the 27 hospitals, observed that 55% of procedures were performed in mission/NGO hospitals, 45% in government hospitals, and <1% in a private hospital. Cleft lip and palate repair was predominately undertaken by plastic surgery teams, with external funding, who performed 80% of 140 operations [58]. Notably the number of operations performed in southwestern Uganda was higher than previous estimates [59]. Walker et al. postulate that the inclusion of NGO and mission hospitals which performed the majority of the procedures accounted for this finding and estimates do not reflect current services available.

As examples of subspecialty surgery, there are only six plastic and reconstructive surgeons in Ghana for a population of 22 million and three in Uganda with a population of 28 million, and in Zambia with a population of 10 million, there is only one [60]. Similarly, there are only six neurosurgeons in Uganda [61]. For urology, Zambia has one trained urologist per 2.3 million people, and most conditions are managed by either general surgeons or nonphysician providers [53]. Though accurate and complete measurements are not yet available, it remains apparent that sufficient personnel for subspecialty surgical care is sorely lacking [62].

Access to Subspecialty Care

Access to subspecialty surgical care is limited in low-resource settings. At least 4.8 billion people do not have access to surgery, including greater than 95% of the population of South Asia and central, eastern, and western sub-Saharan Africa. This compares to the less than 5% of high-income North America, Western Europe, and Australia who lack access to surgery, highlighting the inequitable distribution of healthcare [63].

In most low-income countries, specialty-trained surgeons and anesthesiologists, if available, work exclusively in referral hospitals [64–66]. As a result, district hospitals are staffed by general practitioners and nurses [67]. Even when hospitals are able to provide emergency and essential surgery, their capacity to deliver subspecialty surgical care is often hindered [66, 68]. In a review of hospitals within Haiti, 93% claimed the ability to perform hernia repairs, while more specialized care was limited: operative repair of fractures (51%), clubfoot (42%), cleft repairs (31%), and cataract surgery (27%) [69].

As anyone who has practiced in a LMIC has experienced, patients travel long distances [70–72], often delay seeking treatment [73, 74], and consequently, present with advanced disease. This becomes particularly true with subspecialty surgical care and is true for the authors’ experience with esophageal cancer in western Kenya [75, 76]. A review of the burden of waiting by Poenaru et al. demonstrated significant delays in surgical care and resultant increased burden of disease. They demonstrated prolonged average wait times for pediatric orchidopexy (72 months) and anorectoplasty (74 months) [77] and compared these to much lower wait times in resource-rich Canada.

Millions of people worldwide face catastrophic expenditures from the costs of surgical care and conditions requiring surgery. These prohibitive costs fall mostly upon LMICs and on poor patients within any country [78].

Finances of Subspecialty Surgery

The days of thinking subspecialty surgery is too expensive or a bad investment in low-resource settings are over. Available data and experience point toward massive benefits of life-changing care for individual patients and the resultant improved capacity and infrastructure for communities [21, 79]. Multiple reports suggest the cost-effectiveness of subspecialty surgery: pediatric inguinal hernia repair [80], pediatric neurosurgery [81], orthopedics [82, 83], ophthalmology (cataract [84–88] glaucoma [89] and trachoma [90, 91]), cleft repair [92–95], hand surgery [96], and cardiothoracic surgery [97]. When comparing subspecialty surgery to other public health interventions, the cost-effectiveness profiles are competitive: cleft repair ($47.74 per disability-adjusted life year (DALY), hydrocephalus ($108.74 per DALY), ophthalmic surgery ($136 per DALY), orthopedic surgery ($381.15 per DALY) as compared to BCG vaccine ($51.86–$220.39), and antiretroviral therapy ($453.74–$648.20 per DALY) [98]. High complexity care can reduce costly disabilities while maintaining a cost-effective profile. Pediatric neurosurgery for infant hydrocephalus has been demonstrated to be cost-effective at the permanent referral center of CURE Children’s Hospital of Uganda [99]. Provision of care by local surgeons could be most cost-effective; however, in an era where services are not available, even short-term trips, such as a pediatric neurosurgical brigade to Guatemala, are still more cost-effective than no care at all [81]. These reports are encouraging as they reflect the experience of first-line providers who understand the important role that subspecialty surgical care plays in improving public health.

Various Models for the Provision of Subspecialty Care

The Essentials

-

Numerous models, platforms, or methods of delivery for subspecialty surgical care exists.

-

These models include short-term surgical trips, university and academic partnerships, telemedicine, task shifting/sharing, government initiatives, private health facilities, nongovernmental organizations, and faith-based mission hospitals.

-

Each of these models has various advantages and disadvantages.

-

Delivery of subspecialty care could best be viewed as a continuum with various combinations of these models.

Categorizing each effort into a specific defined platform presents a problem in understanding complex methods of delivery. Although such classification into platforms can greatly inform our understanding of advantages and disadvantages [100], delivery of subspecialty care could perhaps more easily be viewed as a continuum. Often, providers utilize a number of delivery methods to achieve their desired goal. As an example, subspecialists may briefly visit a permanent NGO clinic that partners with faith-based organizations and the local government to address either a specific condition or subspecialty need. Over time, by building on the foundation of short-term service trips, important development can occur, progressing even to a community-owned hospital capable of subspecialty surgery. Trying to describe each method of delivery independently may not be possible, but recognizing the assorted nuances of each variable may facilitate the understanding of the best methods and models available for the needs of a specific community. These findings can then be scaled to the national and global levels. Understanding this continuum of care provision, as seen by first-line providers of subspecialty care, enables appropriate implementation.

There are a number of models for provision of subspecialty surgical care, each with its own advantages and disadvantages (Table 5.2 ). The range includes short-term surgical trips, academic partnerships, government initiatives, nongovernmental organizations, faith-based mission hospitals, and various combinations of these models. We can crudely break these down and describe approaches. The acknowledgment of the methods, personnel, location, and investment of time of each model may delineate how to best provide subspecialty care to a community.

Short-Term Surgical Trips

Historically, the traditional STST is an outsider approach where a group of skilled individuals bring resources, both human and material, to provide medical services. In scientific literature, there are myriad reports of “mission” or “service” trips, which often focus on the volume of patients served. The concept of providing care to a high volume of patients over a brief period of time has been described in numerous terms: surgery camps, brigades, safaris, blitzes, and teams. Since the nineteenth century, faith-based groups have organized, partaken, and advocated for short-term mission trips [19], and surgical groups are among the most represented participants in short-term service [101]. Despite the fact that these groups often share a common goal of encouraging development of the local community, reports and studies are almost uniformly from the perspective of the outsider providers of care and training rather than the receivers [24, 25, 27, 31, 38, 102–105]. This has led to questions about the relevance of such groups from the view of the local community [106].

Advantages of this model include a large volume of patients cared for by an ideally well-trained and capable subspecialist surgeon. The patients with problems that no one has been able to care for in years may have their lives drastically changed. Perhaps, the most dramatic STSTs include quick solutions such as ophthalmology care where sight is immediately restored. These STSTs are attractive to volunteers and are typically reported as positive experiences for the healthcare provider [107]. On the positive side, a short-term trip may be the experience necessary to pique the awareness of an individual so that he or she invests long term in a community [108, 109]. Yet, the long-term impact on patients and communities is rarely reported or understood. Many camps have been successful in developing longstanding commitments to providing care where care would otherwise be unavailable. An example in the ENT subspecialty is the work of BRINOS, Britain Nepal Otology Service, with years of experience sending Nepalese and British ENT surgeons into remote areas lacking ear care [110]. Organizations, such as Resurge International, that have involved plastic and reconstructive surgeons in short-term service trips have also grown to understand the need for long-term partnerships. The group of subspecialist surgeons reported their needs for cooperation with local physicians, predictable presence, emphasis on teaching, and links with structured organizations [111].

STSTs have their drawbacks as well, especially if conducted poorly. While beneficial for the healthcare provider, this model may have the potential to do the most damage to a community. If not done correctly, an STST may amount to “voluntourism” – a perverted form of altruism where providers enjoy the benefits of travel, overstep their qualifications, limit opportunities for local physicians to flourish, are not conducive to health system strengthening, and damage relationships between local healthcare providers and communities in need [112, 113]. During subspecialty camps, a decreased number of elective operations outside the subspecialty offerings are able to be completed at the hospital. Thus, at these times, there are surgeons who could be offering their services, but are unable to do so because of the lack of operating space, an extremely valuable commodity in a resource-constrained hospital [106, 114]. When a large number of visitors descend upon the hospital community, it can be a stressful time with misunderstandings of the local culture. Although these misunderstandings can be partially alleviated by partnerships of the visiting team with local personnel, this must be considered in planning each STST. Typically, there is a considerable amount of logistical work that is required for visitors, which has the potential to overwhelm local staffing. When specialists are already present and actively caring for patients, these brief surgical camps can create more of a burden on the existing infrastructure than necessary [30, 106]. There are examples of relatively poor outcomes during STSTs that could urge caution in their application to deliver surgical care or at least warrant further exploration in causality [29]. It should be recognized that reports of good outcomes or those equivalent to high-resource settings may be the result of poor follow-up and thus a lack of awareness of complications [115]. Although STSTs may eventually advance to longer partnerships and collaboration among organizations, it remains unknown how many of these efforts fall apart as personnel change or lose enthusiasm.

In response to these questions, the academic surgical community and others have responded to STSTs with ample guidelines, warnings, and lessons [116–121] (Table 5.3). With these suggestions, there is now a trend toward discouragement of these STSTs unless there exists no other possible surgical care alternatives [106, 122, 123]. These attitudes of “first do no harm” must not regress into “first do nothing” [124]. Successful surgical camps are particularly relevant for the provision of specialized surgery in low-resource settings where services are otherwise not available. Short-term teams may be necessary to fill these gaps, provide the necessary resources, and build the capacity and infrastructure necessary to advance the project along the continuum of the delivery of subspecialty care.

University and Academic Partnerships

Numerous, important publications describe how universities and resource-rich organizations have developed partnerships, improved educational efforts, and aspired to longitudinal collaboration [21, 22, 125–128]; yet, there is a paucity of descriptions of the organizational efforts from institutions within resource-limited settings. It is important to note that universities, academic institutions, and professional societies in LMICs have been training and supporting surgeons for years before such partnerships. The College of Surgeons of East, Central, and Southern Africa (COSECSA) is an independent, academic organization that encourages postgraduate training in surgery and accredits surgeons [129]. Some university partnerships are based upon short-term care delivery [130], while others focus on developing long-term partnerships, research, and education [131–134]. Advantages of the university partnership are the acknowledgement of common interests and a collaboration toward furthering service, education, and research. A disadvantage is that the resource-rich university often takes the credit for the partnership, while the institution in the resource-poor setting accepts the funding without being invited to the table to make decisions [135]. Hospitals and universities in low-resource settings may take whatever help might be offered, in the hope of acquiring needed resources, from numerous partnerships that may lack the depth or desire to invest in a community. These high-resource partners may benefit from a distinguished, yet shallow, partnership through publications, increased interest among applicants to their program, and recognition. It is still early to discern if recent partnerships between surgical departments will persist despite changing personnel.

Telemedicine

Telehealth is the use of electronic information and telecommunications technology to enable clinical healthcare, education, and administration over long distances [136]. As the availability of technology advances and feasibility improves [137], telemedicine may help with more thorough preoperative workup and evaluation for STSTs [138, 139], remote screening [140], and postoperative follow-up [141]. Telemedicine may also improve educational collaboration and be relevant to continued training, mentoring, and skills development [142–144]. Telesimulation, linking trainees and instructors in simulation through the Internet, has been shown to be promising, teaching laparoscopic skills to surgeons in Botswana and Colombia [145, 146]. As surgeons practicing in a low-resource environment with limited subspecialists available, the authors can personally attest to the importance of discussing complex cases via phone, email, or video conferencing with colleagues trained in subspecialty disciplines.

Task Shifting Versus Task Sharing

Many LMICs and organizations have attempted to overcome surgical disparities by training nonphysicians to perform procedures [147]. Task shifting, the delivery of surgical care by nonphysician providers, has been shown to be a viable solution in some low-resource settings with limited workforces [148]. Nonphysician providers have been advocated in essential surgery [149, 150], obstetrical care [151–153], and even subspecialty surgical care: orthopedics [154], pediatric surgery [155], and select urological and neurosurgical procedures [156]. The advantages of task shifting include the provision of healthcare to communities that would otherwise have no reliable access to care and the reduced cost and time of training physician providers. Disadvantages include the lack of adequate supervision and quality control and the concern that care may be compromised in a low percentage of situations where further training and expertise are necessary. Most advocates for task shifting acknowledge these limitations and recommend a restricted number of procedures be carried out by such providers. Certain subspecialty procedures, such as cataracts, could be adopted by nonphysician providers if appropriate oversight is in place [157]. To help address the lack of access, some subspecialty care such as basic and emergency neurosurgery in Tanzania has been taught by neurosurgeons to nonphysician clinicians. In that model, the trained healthcare workers then taught other healthcare workers to perform basic and emergency neurosurgery independently [158]. Clear definitions of the scope of practice, high standards for accreditation, and shared responsibility and oversight with specialist providers are necessary to ensure safe and quality care by the nonphysician provider [159, 160].

While task-shifting seems like a necessary stop-gap measure in the current era of significant disease burden, we advocate for a task-sharing approach with adequate training of physicians to oversee nonphysician providers [161]. This training model requires the long-term presence of highly trained personnel which results in a remarkable investment of human potential [162]. There are many challenges in training subspecialty surgeons in low-resource settings including a lack of standardization [163–165]. The authors do not advocate for sending personnel to high-resource institutions for further subspecialty training due to their propensity to stay and work in these high-resource settings. Training models appropriate to the resource-level and context should be developed and maintained to provide adequately trained personnel [166].

Government Health Facilities

Within LMICs, government hospitals, or the public sector, provide a variable amount of subspecialty care, and district or county hospitals do not typically offer subspecialty surgery [3, 66, 68, 150, 167, 168]. A review of district government hospitals in Mozambique, Tanzania, and Uganda demonstrated that no general surgeons were present. With essential surgery lacking priority in administration of these hospitals, subspecialty surgical care is not possible [67].

Generalized comparisons of public vs. “private” (including for-profit, nonprofit, faith-based) sectors show that the public sector is perceived to lack the hospitality and timeliness of the private sector [169]. Arguments exist that the public sector may offer expanded coverage to poor patients and is the path toward universal coverage. However, there is no data to guide the debate in subspecialty surgery. Governments often lack commitment to funding subspecialty care and training [170] and sometimes send patients abroad for subspecialty care [33, 171]. Yet, there are encouraging examples of how governments have partnered with institutions to expand and strengthen their specialist workforce [133, 172].

The facilitation of cataract surgery in India during the 1990s is one example of a government-identified need in which subspecialist surgical care was subsidized, expanded, and improved. Each district was allowed to finance providers to accomplish the goal of reducing blindness. Government mobile camps, state medical hospitals, and nongovernmental hospitals had an average cost for each individual patient of $97, $176, and $54, respectively, and resulted in patient satisfaction at 51%, 82%, and 85%, respectively [88].

Where specialists are not locally available within the public sector, there is certainly a role for short-term surgical camps. Though when specialists are already present and actively caring for patients, these brief surgical camps may create more of a burden on the existing infrastructure than necessary [30, 113].

Private, For-Profit Hospitals

Due to perceived problems in the public sector, private for-profit clinics and hospitals are quickly increasing their market share in LMICs, particularly in urban centers [173, 174]. Physicians often have a “dual practice” in a public hospital, such as a university, with a private clinic to supplement income [175]. Fifty-five percent of physicians working in three capital cities in Africa subscribed to this dual practice [176]. Private health facilities have often been small operations, owned by individual practitioners, which then grow over time into larger hospitals [177]. If dual-practice providers have patients in both private and public institutions, the private patients may receive preferential treatment at the expense of patients in public hospitals.

The Muhimbili Orthopedic Institute in Tanzania attempted to overcome the perception that specialty care could only be done at private or NGO facilities. They reported on their acceptance of and recruitment of private patients to maintain a private/public mix. During a 5-year period, private patients accounted for only 30% of outpatient visits and 5% of inpatients, yet generated 77% of the hospital’s income from patient fees and 35% of all hospital income including government subsidies. With their experience, they found that patients prefer the private sector due to poor accommodations and the perceived poor worker-patient relationships in the public sector [178].

Nongovernmental Organizations

Numerous nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or charitable organizations provide surgical care in low-resource settings. It is difficult to quantify the number of NGOs involved in care and equally impossible to estimate their impact. NGOs can be involved in a range of projects, from community-based programs to global efforts based on a surgically correctable condition, and vary widely in their models for delivery [179]. In a review by Ng-Kamstra et al., 313 NGOs were identified delivering surgical care in all 139 LMICs. Subspecialty surgery is performed and supported by numerous NGOs. Of all the NGOs surveyed, a number contributed to some form of subspecialty services including 22% of NGOs which perform cleft repair and 28% of NGOs which provide ophthalmology care [180].

Some NGOs are devoted to a specific condition, while others focus on a specific subspecialty. Smile Train is the largest charity group aimed at the subspecialty surgery of cleft repair. As a condition recognized to cause significant morbidity without operative repair, Smile Train has funded thousands of operations through local institutions and trained scores of local providers [181]. Throughout the last 20 years, a nonprofit organization, IVUMed, has supported educational programs for urology through numerous partnerships. In over 30 countries, IVUMed has worked in conjunction with a network of providers, institutions, societies, and industry to create collaboration built on training the subspecialty surgical discipline of urology [182]. Each NGO has a role in reducing the surgical burden of disease within its own area of strength.

NGOs are often involved in multiple delivery models even within their own organizations; 66% utilize STSTs and 68% claim to have long-term partnerships [180]. This allows us to draw comparisons between models within an NGO. One interesting example comparing the STST to a permanent center was done by Nagengast et al. in India [183]. They reviewed the costs associated with providing cleft repair during surgical missions, or short-term trips, to a center developed and staffed in an area found to have a high burden of disease from clefts. They found a 40% decrease in cost per surgery for the center as compared to the mission and a different distribution of expenses. Within the STST, air travel (52%) and hotel expenses (22%) were the largest expenses. In contrast, the center’s budget expenses were attributed to salaries (46%) and infrastructure costs (20%). This finding reflects a goal of rewarding institutions that shift aid dollars toward the local economy and should encourage the movement of partnerships along the continuum of care delivery.

Faith-Based Mission Hospitals

The aforementioned era of physicians and surgeons motivated by faith, who first recognized the importance of providing surgical care to a low-resource community, consequently helped to build mission hospitals, and devoted lifetimes to service, did not disappear entirely. They, along with their local counterparts, have continued to invest in their surrounding communities with access to hard-to-reach populations and a priority on serving poor and marginalized people [184]. Faith-based organizations still account for a significant percentage of global healthcare provision, estimated at 20–70% of the health infrastructure in Africa [185–188]. However, these estimates are markedly different for individual countries and communities and cannot be generalized to all low-resource settings [189, 190]. Currently, there are numerous faith-based hospitals operating in resource-limited areas throughout the world, and there is a growing awareness that faith-based organizations play an important role in the delivery of global healthcare [191]. These mission hospitals and the surgeons that help staff them have long been and continue to be an incredible asset to the communities in which they serve [192, 193]. Within their communities, they are typically among the best choices for care, with high patient satisfaction rates [194], and in some areas the only choice that exists. Mission hospitals tend to adapt to the desired needs of the community, and subspecialist care is provided for the given need [39, 42, 75]. There is great potential for academic surgery to partner with faith-based organizations that offer cross-cultural experience and context-appropriate surgical knowledge, which is essential for a successful training model [161, 191]. Nevertheless, disadvantages of this model have been noted. There can be the perception of weak governance at the administrative level [195], but when compared to teaching and district hospitals, a mission hospital had the highest management ratings [196]. Any management issues are contrasted by a motivated staff providing service exceeding expectation [197, 198]. A possible lack of collaboration with government institutions could reduce the achievement of universal health access as mission hospitals are often not accounted for within the organization and implementation of health planning and policy [190].

The Continuum of Delivery of Subspecialty Surgery

While in some situations, the delivery of healthcare is achieved through a pure form of one of the above models, the most successful and “sustainable” programs usually employ some combination. By recognizing that the delivery of healthcare to low-resource settings is a continuum, it enables stakeholders to realize that no model, in of itself, is wrong; rather, all are working toward the same goal: universal, affordable access to subspecialty surgical care.

Within this continuum, partnerships are instrumental to success [199]. Collaboration and networking have a role among surgical subspecialists who have similar interests in reducing health disparities. A unique collaborative effort among subspecialists exists within the pediatric surgery community, with surgeons delivering care through multiple platforms and models. With an emphasis on networking, educational efforts, research, and advocacy, this global network of surgeons helps to encourage and advance the cause of pediatric surgical care in low-resource settings [200]. Learning from others’ experiences in the provision of care within similar resource-limited settings can help to overcome challenges and provide encouragement.

Until access to subspecialty surgical care is universally available, there will be a need for outside personnel and resources. The key to providing the best possible care is to balance each of the advantages and disadvantages of different models to create the ideal template for the individual region, nation, and community.

Classification of Models

The Essentials

-

Models can be understood through time, personnel, and location.

-

Long-term investment in a community is a goal. Where this is not possible, shorter duration of care, but only if conducted effectively, is better than no care at all.

-

There is a balance of personnel providing subspecialty care where “outsiders” offer expertise while “insiders” offer effective provision of care that is culturally relevant.

-

The benefits from the referral of subspecialty care must be balanced with appropriate access to care.

These various models can be understood through different means. The investment of time, the location, and the personnel delivering care help to inform the advantages and disadvantages of each model. With this understanding, one can draw conclusions for the appropriateness of the model to a community.

Classification by Time Investment

Perhaps the most notable distinction in the various care delivery models is the amount of time the individual or team providing subspecialty surgery invests in a particular community. The time invested can vary from a few days of an STST to decades of development by a community-owned hospital offering specialty services (Table 5.4). Although difficult to generalize, it can still be informative to evaluate the type of delivery platform and the time desired to attain the goals of providing subspecialty surgical care to a community. The duration of partnership between hospitals and Smile Train, a large international NGO, showed improvement in surgical care, patient follow-up, increased number of trainees, and additional ancillary services [201]. As STSTs develop over time, outcomes improve [28, 202].

It is our view that long-term investment in a community is a goal during the provision of subspecialty surgical care. Where this is not possible, shorter duration of care, but only if conducted effectively, is better than no care at all.

Classification by Personnel

Some models rely on the presence of “outsider” personnel with the necessary skills to provide specialist care. Others focus on local or “insider” providers trained to do specific operations. Most care providers acknowledge some balance in this spectrum in order to deliver optimal care to a population (Table 5.5).

A sometimes contentious issue of who should be providing subspecialty care allows us to classify these models of delivery by the personnel’s understanding of the local culture and community. This understanding is a key to success in the delivery of quality care and is closely tied to the time invested by an outsider subspecialist. Time learning language, culture, and investing in relationships [203] may result in an “outsider” having a more complete understanding of a local community than a national government. The transfer of skills through training can also accomplish this aim. We should be clear that the reciprocal benefits of cross-cultural collaboration exceed the pure transfer of skills and resources [108]. So, the goal is not for complete transition from the cultural outsider to the insider, but for long-term exchange of ideas, skills, and ingenuity. Rewarding cross-cultural experiences can be fulfilling to both partners as demonstrated by collaborative neurosurgical training in Ethiopia [204]. There is too much to gain from both sides working alongside one another to unbalance the scale toward one side or another.

Classification by Location

Similar to resource-rich countries, outcomes for subspecialist care are better at referral centers with high volumes of specific conditions [205, 206] and when performed by experienced subspecialty surgeons [207–209]. This acceptable referral benefit must be balanced with appropriate access, especially due to the burden of travel expenses on poor patients [70] (Table 5.6).

Comparisons of models for subspecialty surgery are limited. But a study from Peru examined surgical outcomes after cleft lip and palate repair. When comparing location of operation, whether a mission model or a private referral center, and while controlling for surgeon and technique, the authors found that the mission model showed an increased complication rate [210]. An Ecuadorian study found similar results with the complication of palatal fistula ten times more likely in the mission model than the private center [30]. Moving along the continuum from surgical camp to referral center seems to also have cost-savings implications as well. Hackenberg et al. compares 17 STSTs and a comprehensive care center for cleft lip and palate surgery in Guwahati, India. The researchers found that the cost/disability-adjusted life year ranged from $247/DALY through medical missions to $190/DALY at the center [95].

The Tenwek Hospital Experience

The Essentials

-

Tenwek Hospital, a faith-based mission hospital, utilizes a number of models to provide subspecialty surgical care.

-

To meet a significant need, a successful cardiac surgery program has developed through the investment of time, training of personnel, and improvements in infrastructure.

-

The Tenwek Hospital experience demonstrates that the progression from temporary, short-term teams to self-sustaining independent care is truly a continuum.

The particular experience of Tenwek Hospital is an example in several areas of moving along this continuum from very short-term isolated advancement to sustainable programs providing capacity building and training of local healthcare providers in an independent setting. Tenwek Hospital is a 300-bed mission hospital in southwestern Kenya. It began as a small clinic in the late 1930s staffed by American missionary nurses. A full-time American missionary doctor joined the staff in 1959, and the hospital began to grow rapidly throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1980s, a nurse training school was begun with a goal of providing higher-level training for local nurses, and providing a reliable source of nurses for the hospital, thus making it less reliant on outside resources. In the late 1990s, the hospital began cooperating with the national Ministry of Health in providing internship training for new graduates of Kenyan medical schools. In the early 2000s, a program of residency training was established in family medicine, followed by a general surgical residency in 2008 and an orthopedic surgery residency in 2014. Currently, there are more than 35 African doctors training at Tenwek Hospital in postgraduate medical programs. In addition to this, Tenwek serves as a clinical rotation site for many Kenyan medical students from a variety of medical schools around the country. Graduates from these programs are taking up posts around the country, and throughout other African countries, providing reliable, cost-effective healthcare to large areas of the region.

Development of subspecialty care was also occurring during these years at Tenwek Hospital. With the arrival of a full-time American thoracic surgeon in 1997 (R. White), Tenwek began to be able to offer more advanced pulmonary and esophageal surgery. Given the very high incidence of esophageal cancer in the region [76, 211], Tenwek soon became the regional referral center for thoracic surgery. When the general surgical residency became fully functional, residents were exposed to thoracic surgical training in a more extensive way than in most general surgical residency programs. By the completion of 5 years of general surgical training, graduates of the Tenwek General Surgical Residency Program usually feel quite comfortable with esophagectomy and basic pulmonary resection techniques.

Different types of subspecialty surgery require different investments of time and infrastructure. Some areas of subspecialty surgery require relatively short, prescribed times of training and limited changes in infrastructure and equipment. Examples of this include cleft lip repair and pedicled soft tissue transfers in the area of plastic surgery. Other areas, such as advanced laparoscopy [212, 213], require more careful planning and outlay of capital investment and infrastructure. Then there are other areas, such as cardiac surgery, which have extensive requirements for training, infrastructure, and physical facilities [33, 44, 214–216]. In these areas, it often requires a “quantum leap” to move into them, rather than a gradual introduction of new procedures and techniques.

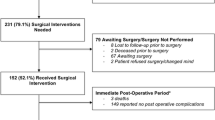

Rheumatic heart disease is endemic in the area around Tenwek Hospital. Most patients present with advanced valvular disease at a stage when valve replacement is the only reasonable option. In fact, many present when myocardial function has suffered so severely that any surgical intervention is extremely dangerous. Although the need was clear, it initially seemed that the training, technology, and infrastructure requirements were so monumental that it would not be wise to embark upon a program of cardiac surgery at Tenwek Hospital. Cardiac surgery made its first appearance at Tenwek Hospital in 2007 through an unusual circumstance. A personal friend of one of the authors (R. White) is an American cardiac surgeon who visited Kenya that year with a view toward starting a cardiac program at one of the government facilities in the country. After visiting several facilities, he became convinced that those particular institutions lacked the necessary infrastructure to begin such a program. With several days of extra time remaining in his planned trip, he visited Tenwek Hospital. Seeing the burden of disease and the existing infrastructure, he challenged us at Tenwek to consider beginning a cardiac program. This began with several cases of mitral commissurotomies for severe mitral stenosis performed with no cardiopulmonary bypass. Success in these cases encouraged us to plan for acquisition of all the necessary equipment to prepare for open heart cases requiring cardiopulmonary bypass. The open heart program began very clearly with short-term surgical trips, with teams coming regularly from Brown University, Vanderbilt University, Maine Medical Center, and the Ocala Heart Institute. These teams would consist of surgeons, perfusionists, cardiologists, anesthesiologists, and critical care physicians and nurses. During the first few STSTs, the visiting team members carried out virtually all of the direct patient care. However, within a short time, a very purposeful transference of knowledge and skills began to occur. Through specific times of didactic and hands-on-learning, the Tenwek staff began to take over areas of critical care medicine and nursing, cardiac anesthesia, and perfusion, while the author (R. White) resurrected cardiac skills not practiced for many years. It was very gratifying for the STSTs to find themselves less required for direct care and spending more and more time perfecting the skills in the Tenwek staff. Likewise, the local staff found that their ability to care for other critical, noncardiac patients improved considerably during this time. After 4 years of visiting teams, it seemed an appropriate time for the Tenwek team to begin open heart cases in the absence of visiting teams. To date, we have completed nearly 300 open heart cases at Tenwek Hospital, with about 2/3 of these performed with visiting teams present and 1/3 done solo. This has been achieved with a perioperative mortality rate of less than 1%. Currently, straightforward cases are handled by the Tenwek staff, while riskier cases and small pediatric cases are saved for the STSTs.

From this example, it is clear that this progression from temporary, short-term teams to self-sustaining independent care is truly a continuum. Tenwek Hospital has made significant progress along this continuum; yet, there remains much to accomplish. Tenwek continues to depend on outside help for some areas of equipment procurement and in management of complex cases. However, it seems inevitable that this progress will continue.

Role of Subspecialty Care in Reducing Disparities in Global Surgery

The Essentials

-

Subspecialty surgical care provides benefits not only to the individual patient but also to the community at large.

-

Since subspecialty care requires certain infrastructure and training, other healthcare priorities can benefit from its implementation.

-

Enhanced ability to care for patients improves acceptance of primary care.

Over time, the care of the individual benefits the community at large by improving its access to healthcare, infrastructure, skilled personnel, and microeconomics [217]. Through the examples of Tenwek Hospital and others, the associated improvements surrounding the implementation of subspecialty surgical care become apparent.

Building Infrastructure and Capacity

Considerable infrastructure is often required for subspecialist surgery. With this infrastructure, other departments reap the benefits as well [218–220]. Improvements in anesthesia care benefit all surgical patients. The laboratory and blood banking capabilities [221] are able to withstand the shock of the subspecialty care and are thus better prepared for both challenges and routine care. The screening program has both stemmed from and advanced the community health and primary care programs at Tenwek Hospital [222]. Radiology [223] benefits from enhancements in echocardiography and ultrasound. Donated equipment is provided, but biomedical engineers work together with the hospital maintenance department to ensure equipment does not fall into disrepair and abandonment [224, 225]. The potential for curative intervention improves outpatient relationships. The hospital administration [196, 226] fosters the growth and development of a program to help build a major referral center [227].

Improving Personnel Skills and Retention

As departments improve, it is only through the personnel that guide them. At Tenwek, the nursing staff and operating room technicians have been involved in the cardiac camps, and the eagerness to strive for excellent cardiac care helps in the care of all patients. Personnel have readily participated in improvement of critical care [228]. And, there is a greater willingness and ability to take care of patients who are critically ill.

Improving Community Access and Care

In communities with a distrust of modern medicine, the successful treatment of an individual should not be disparaged as a lack of investment into community. Inspirational stories of recovery and treatment can encourage a community to seek care at that hospital and surrounding healthcare facilities. It is difficult to quantify the impact on a community from the care of an individual. Anecdotal experience from Tenwek Hospital demonstrates increased participation in screening programs and public health ventures among communities with direct knowledge of previous patients’ treatments and recovery. The Tenwek cardiac program has improved the lives of a number of individuals. Yet, it has also improved the care that the hospital provides to the community. The excellent care of an individual patient is evidence that inspires that patient’s community.

As the cardiac program has progressed, numerous referrals for cardiac care from outside institutions have occurred, and reciprocal referrals from Tenwek to outside institutions for other specialty services have improved. This advantage has improved not only the perception of the local community but awareness in the national healthcare system. Additionally, these referrals improve communication and connect providers, all trying to deliver optimal healthcare to a large population in need.

Role of the Individual Subspecialty Surgical Provider

The Essentials

-

The key question is not related to where along this continuum the individual provider finds himself or herself, but rather that he or she is moving in the right direction.

-

It is helpful to consider strategic questions prior to becoming involved in subspecialty surgical care.

-

Involvement in subspecialty surgical care and its advancement within low-resource settings can be extremely rewarding for all involved.

Understanding the Model of Care and Making Progress on the Continuum

The role of the individual provider in delivering subspecialty surgical care in low-resource settings is often described as a dichotomous choice between two extremes that is phrased something like this: “is the goal of the surgeon to directly care for a handful of individual patients, and in so doing provide himself/herself with the self-satisfaction of having reached out to those of a lower socioeconomic status, or is it to selflessly empower local caregivers to develop independence and skill in caring for complex cases and situations to the extent that eventually the external provider’s presence will no longer be required?” Common to many situations in life in which a multileveled process is reduced to a dichotomous decision, the appropriate answer to the question as phrased here is probably simply “Yes.” Of course the individual provider will hopefully be changing the lives of a small group of actual patients during his or her time in a given situation. And of course, this should reasonably bring satisfaction to the provider who is reaching out to a group of people who may not enjoy all the privileges that the individual provider has available. But this does not need to be exclusive of the goals of developing sustainable programs which empower local caregivers to provide this care in the future as well. As has been described in this chapter, providing subspecialty care in low-resource communities represents a continuum of development. The key question is not related to where along this continuum one finds himself or herself, but rather that he/she is moving in the right direction.

In this same train of thought, subspecialty surgical programs are in a unique position to contribute to the research literature in their endeavors within LMICs. However, this also needs to be done with the same thoughtful consideration of developing local capacity and infrastructure. Academic affiliations with STSTs and longer-term teams can be very effective in fostering an environment of inquiry and research [229–231]. Both institutional and individual partnerships can be sought to benefit both the visiting teams and the local providers, in addition to the population being served. Once again, this is often not a simple dichotomous question of “either/or,” but rather “both/and,” as long as care is taken in planning to truly achieve a “both/and” result.

There are also a variety of very practical issues which should be considered by any individual subspecialty provider engaged in this type of work. Particularly in the area of STSTs, these relevant questions (by no means an exhaustive list!) should be considered (Table 5.7).

Words of Caution

Programs offering subspecialty surgical care often fail to achieve long-term stability and independence for a variety of reasons. Frequently, the driving force behind the initiation of the program is the interest of the individual or group dedicated to that specialty, rather than a real need within the community. In some cases, communities will accept outside input in areas with minimal need, with the hope that the providers will eventually bring something of more benefit to the community. This can lead to disappointment in the minds of the providers and a feeling of being “used” for ulterior motives. When subspecialty surgical care requires significant physical materials (as in the case of cardiac surgery), there is often little thought about the long-term supply of these materials. When local staff are given inappropriate or incomplete training, there can easily develop a feeling among the staff that they have been “used and abused.” Finally, introduction of subspecialty care will necessarily have some effect on the provision of other care within the institution (either in a positive or negative fashion). It is therefore wise to consider the ramifications for the existing infrastructure. With these thoughts in mind, it is helpful to consider the questions in Table 5.8 when considering involvement in a program of subspecialty surgical care.

Words of Encouragement

Despite such warnings, involvement in subspecialty surgical care and its advancement within low-resource settings can be extremely rewarding. Regardless of the model, participation in delivering surgical care to people in need can be immensely satisfying to all involved. The cross-cultural experience and collaboration to solve difficult problems are fulfilling. Providers, including the most specialized surgeon, should be quick to learn from their colleagues. Practicing in resource-limited settings can foster innovation [232–239] and benefit not only the recipients of care but the providers.

Conclusion

Surgery has only recently been considered a global health priority, and subspecialty surgery remains an even newer area of consideration. Yet, more and more data are emerging that support the cost-effectiveness, practicality, and numerous benefits of prioritizing the provision of many subspecialty surgical services to communities in need. Models for delivering subspecialty care are numerous, and the most efficacious method of delivery is variable region to region and country to country, likely requiring a combination of multiple models. As the proponents of global surgical care, and specifically subspecialty surgery, continue to work toward a goal of quality surgical care for all, it must be with an awareness of past mistakes and shortcomings. We must also recognize the successes of particular organizations and programs as examples and standards of how such care can be offered capably, responsibly, and successfully, even in the most resource-constrained setting. We believe excellent, compassionate care of patients through subspecialty surgery can not only significantly impact the lives of the individual patients but will also improve the care of the community and as such should be a global health priority.

References

Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, et al. Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 2015;386(9993):569–624.

Galukande M, von Schreeb J, Wladis A, et al. Essential surgery at the district hospital: a retrospective descriptive analysis in three African countries. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000243. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000243.

Grimes CE, Law RS, Borgstein ES, Mkandawire NC, Lavy CB. Systematic review of met and unmet need of surgical disease in rural sub-Saharan Africa. World J Surg. 2012;36(1):8–23.

Lett R. International surgery: definition, principles, and Canadian practice. Can J Surg. 2003;46(5):365–72.

Gulick EV. Peter Parker and the opening of China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Harvard Studies in American-East Asian Relations; 1973.

Johnson WD. Surgery as a global health issue. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4:47. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.110030.

Rohde J, Cousens S, Chopra M, et al. 30 years after Alma-Ata: has primary health care worked in countries? Lancet. 2008;372(9642):950–61.

Lowenson R. Structural adjustments and health policy in Africa. Int J Health Serv. 1995;23:717–30.

Turshen M. Privatizing health services in Africa. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 1999.

Kuehn BM. Global shortage of health workers, brain drain stress developing countries. JAMA. 2007;298:1853–5.

McQueen KA, Casey KM. The impact of global anesthesia and surgery: professional partnerships and humanitarian outreach. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2010;48(2):79–90.

Mullan F. Health, equity, and political economy: a conversation with Paul Farmer. Health Aff. 2007;26:1062–8. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.1062.

Jack A. ‘Brain drain’ puts Africa’s hospitals on the critical list. In: Cole F, editor. U.S. national debate topic, 2007–2008: healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa. The Reference shelf, (Volume 79, No. 3). H.W. Wilson, Bronx, NY: 2007. p. 104–8.

Tankwanchi ABS, Ozden C, Vermund SH. Physician emigration from sub-Saharan Africa to the United States: analysis of the 2011 AMA physician masterfile. PLoS Med. 2013;10(9):e1001513.

Boratyñski J, Chajewski L, Hermelin’ski P, Szymborska A, Tokarz B. Visa policies of European Union member states, monitoring report. Stefan Batory Foundation; 2006.

Shinn D. African migration and brain drain. Paper presented at the Institute for African Studies and Slovenia Global Action, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 20 June, 2008.

Kalipeni E. The brain drain of health care professionals from sub-Saharan Africa: a geographic perspective. Prog Dev Stud. 2012;12:153–71.

Crisp N, Chen L. Global supply of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:950–7.

Sykes KJ. Short-term medical service trips: a systematic review of the evidence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):e38–48.

Casey KM. The global impact of surgical volunteerism. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87(4):949–60.

Chao TE, Riesel JN, Anderson GA, et al. Building a global surgery initiative through evaluation, collaboration, and training: the Massachusetts General Hospital experience. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(4):e21–8. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.12.018.

Lipnick M, Mijumbi C, Dubowitz G, et al. Surgery and anesthesia capacity-building in resource-poor settings: description of an ongoing academic partnership in Uganda. World J Surg. 2013;37(3):488–97.

Rumstadt B, Klein B, Kirr H, et al. Thyroid surgery in Burkina Faso, West Africa: experience from a surgical help program. World J Surg. 2008;32(12):2627–30.

Cheng LH, McColl L, Parker G. Thyroid surgery in the UK and on board the Mercy Ships. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50(7):592–6.

Sykes KJ, Le PT, Sale KA, Nicklaus PJ. A 7-year review of the safety of tonsillectomy during short-term medical mission trips. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(5):752–6.

Snidvongs K, Vatanasapt P, Thanaviratananicha S, Pothaporna M, Sannikorna P, Supiyaphuna P. Outcome of mobile ear surgery units in Thailand. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;124(4):382–6.

Horlbeck D, Boston M, Balough B, et al. Humanitarian otologic missions: long-term surgical results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(4):559–65.

Barrs DM, Muller SP, Worndell DB, Weidmann EW. Results of a humanitarian otologic and audiologic project performed outside of the United States: lessons learned from the “Oye, Amigos!” project. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(6):722–7.

Huijing MA, Marck KW, Combes J, et al. Facial reconstruction in the developing world: a complicated matter. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;49(4):292–6.

Maine RG, Hoffman WY, Palacios-Martinez JH, et al. Comparison of fistula rates after palatoplasty for international and local surgeons on surgical missions in Ecuador with rates at a craniofacial center in the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(2):319e–26e.

Cousins GR, Obolensky L, McAllen C, Acharya V, Beebeejaun A. The Kenya orthopedic project. Surgical outcomes of a traveling multidisciplinary team. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94-B(12):1591–4.

Adams C, Kiefer P, Ryan K, et al. Humanitarian cardiac care in Arequipa, Peru: experiences of a multidisciplinary Canadian cardiovascular team. Can J Surg. 2012;55(3):171–6.

Falese B, Sanusi M, Majekodunmi A, et al. Open heart surgery in Nigeria; a work in progress. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;8:6.

Swain JD, Pugilese DN, Mucumbitsi J, et al. Partnership for sustainability in cardiac surgery to address critical rheumatic heart disease in sub-Saharan Africa: the experience from Rwanda. World J Surg. 2014;38(9):2205–11.

Tefuarani N, Vince J, Hawker R, et al. Operation open heart in PNG, 1993–2006. Heart Lung Circ. 2007;16(5):373–7.

Young S, Lie SA, Hallan G, et al. Risk factors for infection after 46,113 intramedullary nail operations in low – and middle-income countries. World J Surg. 2013;37(2):349–55.

Jenkins KJ, Castaneda AR, Cherian KM, et al. Reducing mortality and infections after congenital heart surgery in the developing world. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1422–30. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0356.

Novick WM, Stidham GL, Karl TR, et al. Are we improving after 10 years of humanitarian paediatric cardiac assistance? Cardiol Young. 2005;15(4):379–84.

Gathura E, Poenaru D, Bransford R, Albright AL. Outcomes of ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion in sub-Saharan Africa. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(5):329–35.

Kulkrani AV, Warf BC, Drake JM, et al. Surgery for hydrocephalus in sub-Saharan Africa versus developed nations: a risk-adjusted comparison of outcome. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1711–7.

Meier DE, Tarpley JL, Imediegwu OO, et al. The outcome of suprapubic prostatectomy: a contemporary series in the developing world. Urology. 1995;46(1):40–4.

Stephens KR, Shahab F, Galat D, et al. Management of distal tibial metaphyseal fractures with the SIGN intramedullary nail in 3 developing countries. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(12):e469–75. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000396.

Leon-Wyss JR, Veshti A, Veras O. Pediatric cardiac surgery: a challenge and outcome analysis of the Guatemala effort. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2009:8–11. doi:10.1053/j.pcsu.2009.01.003.

Gnanappa GK, Ganigara M, Prabhu A, et al. Outcome of complex adult congenital heart surgery in the developing world. Congenit Heart Dis. 2011;6(1):2–8.

Schönmeyr B, Wendby L, Campbell A. Early surgical complications after primary cleft lip repair: a report of 3108 consecutive cases. Cleft Palate-Craniofac J. 2015;52(6):706–10.

Mathers C, Fat DM, Boerma JT. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. World Health Organization; Geneva; 2008.

UNICEF. The state of the world’s children 2009. UNICEF; New York, NY; 2009.

Rao GN, Khanna R, Payal A. The global burden of cataract. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(1):4–9.

Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, Montico M, Brumatti LV, Bavcar A, Grasso D, Barbiero C, Tamburlini G. Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36226.

Bickler SW, Rode H. Surgical services for children in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2002 Oct;80(10):829–35.

Stanley CM, Rutherford GW, Morshed S, Coughlin RR, Beyeza T. Estimating the healthcare burden of osteomyelitis in Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104(2):139–42.

Metzler IS, Nguyen HT, Hagander L, et al. Surgical outcomes and cultural perceptions in international hypospadias care. J Urol. 2014;192(2):524–9. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.101.

Campain NJ, MacDonagh RP, Mteta KA, McGrath JS, BAUS Urolink. Global surgery – how much of the burden is urological? BJU Int. 2015;116(3):314–6. doi:10.1111/bju.13170.

Manganiello M, Hughes CD, Hagander L, et al. Urologic disease in a resource-poor country. World J Surg. 2013;37(2):344–8.

Mossey PA, Modell B. Epidemiology of oral clefts 2012: an international perspective. In: Cobourne MT, editor. Cleft lip and palate. Epidemiology, aetiology and treatment. Front oral biol. Basel: Karger; 2012. p. 1–18. doi:10.1159/000337464.

Wu VK, Poenaru D, Poley MJ. Burden of surgical congenital anomalies in Kenya: a population-based study. J Trop Pediatr. 2013;59(3):195–202.

Hoyler M, Finlayson SR, McClain CD, et al. Shortage of doctors, shortage of data: a review of the global surgery, obstetrics, and anesthesia workforce literature. World J Surg. 2014;38(2):269–80.

Walker IA, Obua AD, Mouton F, Ttendo S, Wilson IH. Paediatric surgery and anaesthesia in south-western Uganda: a cross sectional survey. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(12):897–906.

Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008;372(9633):139–44. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60878-8.

Semer NB, Sullivan SR, Meara JG. Plastic surgery and global health: how plastic surgery impacts the global burden of surgical disease. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(8):1244–8.

Fuller A, Tran T, Muhumuza M, Haglund MM. Building neurosurgical capacity in low and middle income countries. Neurol Sci. 2016;3:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ensci.2015.10.003.

Krishnaswami S, Nwomeh BC, Ameh EA. The pediatric surgery workforce in low and middle income countries: problems, and priorities. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 2016;25(1):32–42.

Alkire BC, Raykar NP, Shrime MG, et al. Global access to surgical care: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(6):e316–23.

Dorman SL, Graham SM, Paniker J, Phalira S, Harrison WJ. Establishing a children’s orthopaedic hospital for Malawi: a review after 10 years. Malawi Med J. 2014;26(4):119–23.

Lavy C, Tindall A, Steinlechner C, Mkandawire N, Chimangeni S. Surgery in Malawi – a national survey of activity in rural and urban hospitals. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(7):722–4.

Notrica MR, Evans FM, Knowlton LM, McQueen KA. Rwandan surgical and anesthesia infrastructure: a survey of district hospitals. World J Surg. 2011;35(8):1770–80.

Kruk ME, Wladis A, Mbembati N, et al. Human resource and funding constraints for essential surgery in district hospitals in Africa: a retrospective cross-sectional survey. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000242. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000242.

Knowlton LM, Chackungal S, Dahn B, et al. Liberian surgical and anesthesia infrastructure: a survey of county hospitals. World J Surg. 2013;37(4):721–9. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-1903-2.

Tran TM, Saint-Fort M, Jose MD, et al. Estimation of surgery capacity in Haiti: nationwide survey of hospitals. World J Surg. 2015;39(9):2182–90.

Faierman ML, Anderson JE, Assane A, et al. Surgical patients travel longer distances than non-surgical patients to receive care at a rural hospital in Mozambique. Int Health. 2014; doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihu059.

Melese M, Alemayehu W, Friedlander E, Courtright P. Indirect costs associated with accessing eye care services as a barrier to service use in Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9(3):426–31.

Zafar SN, Fatmi Z, Igbal A, Channa R, Haider AH. Disparities in access to surgical care within a low income country: an alarming inequity. World J Surg. 2013;37(7):1470–7.

Cadotte DW, Viswanathan A, Cadotte A, et al. The consequence of delayed neurosurgical care at Tikur Anbessa Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. World Neurosurg. 2010;73(4):270–5.

Chao TE, Burdic M, Ganjawalla K, et al. Survey of surgery and anesthesia in Ethiopia. World J Surg. 2012;36(11):2545–53.

White RE, Parker RK, Fitzwater JW, Kasepoi Z, Topazian M. Stents as sole therapy for oesophageal cancer: a prospective analysis of outcomes after placement. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(3):240–6.

Parker RK, Dawsey SM, Abnet CC, White RE. Frequent occurrence of esophageal cancer in young people in western Kenya. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23(2):128–35.

Poenaru D, Pemberton J, Cameron BH. The burden of waiting: DALYs accrued from delayed access to pediatric surgery in Kenya and Canada. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(5):765–70.

Shrime MG, Dare AJ, Alkire BC, O’Neill K, Meara JG. Catastrophic expenditure to pay for surgery: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:S38–44.

Hughes CD, Babigian A, McCormack S, et al. The clinical and economic impact of a sustained program in global plastic surgery: valuing cleft care in resource-poor settings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(1):87e–94e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e318254b2a2.

Eeson G, Birabwa-Male D, Pennington M, Blair GK. Costs and cost-effectiveness of Pediatric Inguinal Hernia Repair. World J Surg. 2015;39:343–9.

Davis MC, Than KD, Garton HJ. Cost effectiveness of a short-term pediatric neurosurgical brigade to Guatemala. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(6):974–9.

Chen AT, Pedtke A, Kobs JK, et al. Volunteer orthopedic surgical trips in Nicaragua: a cost-effectiveness evaluation. World J Surg. 2012;36(12):2802–8.

Gosselin RA, Gialamas G, Atkin DM. Comparing the cost-effectiveness of short orthopedic mission in elective and humanitarian situations in developing countries. World J Surg. 2011;35:951–5.

Marseille E. Cost effectiveness of cataract surgery in a public health eye care programme in Nepal. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:319–24.

Baltussen R, Sylla M, Mariotti SP. Cost-effectiveness analysis of cataract surgery: a global and regional analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:338–45.

Lansingh VC, Carter MJ, Martens M. Global cost-effectiveness of cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1670–8.

Kuper H, Polack S, Mathenge W, et al. Does cataract surgery alleviate poverty? Evidence from a multi-centre intervention study conducted in Kenya, the Philippines and Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e15431. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015431.

Singh AJ, Garner P, Floyd K. Cost–effectiveness of public-funded options for cataract surgery in Mysore, India. Lancet. 2000;355:180–4.

Wittenborn JS, Rein DB. Cost-effectiveness of glaucoma interventions in Barbados and Ghana. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88:155–63.

Evans TG, Ranson MK, Kyaw TA, Ko CK. Cost effectiveness and cost utility of preventing trachomatous visual impairment: lessons from 30 years of trachoma control in Burma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:880–9.

Baltussen RM, Sylla M, Frick KD, Mariotti SP. Cost-effectiveness of trachoma control in seven world regions. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2005;12:91–101.

Corlew DS. Estimation of impact of surgical disease through economic modeling of cleft lip and palate care. World J Surg. 2010;34:391–6.

Magee WP, Vander Burg R, Hatcher KW. Cleft lip and palate as a cost-effective health care treatment in the developing world. World J Surg. 2010;34:420–7.