Abstract

As social pressure to adhere to accepted standards recedes, individuals are freer to choose their preferred family arrangement. But their choices do not always follow a strictly rational approach: rather, they appear to be guided by a trial-and-error logic, which implies contradictions, loss of efficiency and, occasionally, low personal satisfaction. Modern welfare states, while supporting freedom of choices (which includes the possibility of change: e.g. divorce, or medically assisted fertility in one’s late years), must combine this with other targets, ranging from the empowerment of women to the protection of the weak (children, especially), to a system of incentives that eventually ensures socially acceptable outcomes, including a sufficient level of fertility. The now undisputed primacy of the individual will not destroy families, but it will deeply transform them, and increase their heterogeneity: relationships will increase in number but decrease in duration and intensity.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Labour Market

- Subjective Expectation

- Labour Market Situation

- Childbearing Intention

- Advanced Industrial Society

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 The “Pursuit of Happyness”

“The Pursuit of Happyness” (yes, misspelt) is a 2006 movie directed by Gabriele Muccino, based on the autobiography of Chris Gardner, once a homeless, now a successful stock broker. It is not totally clear whether the happiness that Gardner eventually achieves depends on his success in economic or in family matters. Both, probably, since both began badly and ended well. Chris, who never knew his father (well, yes, much later: at the age of 28), spent his childhood in poverty with his mother, his older sister, two more stepsiblings and an often drunk and violent stepfather. Chris’s mother was imprisoned twice: first, when his stepfather falsely accused her of cheating on welfare, and then when she took revenge and tried to kill him by burning their house down—with him inside. Chris and his siblings went to foster care, but the beloved uncle they lived with drowned in the Mississippi River when Chris was just 9 years old. As an adult, Chris got married, but then started an affair with a younger girl, who got pregnant and gave birth to his son, Chris Jr. Understandably, his wife divorced him, but his new partner too abandoned him, shortly after, when Chris was imprisoned for debts. Fresh out of jail, he and his son, just a toddler then, lived as homeless for almost a year, with no money and no family support. Scarce prospects indeed for happiness, and yet …

The pursuit of Happiness (but this once spelt correctly) is also listed, after Life and Liberty, among the unalienable rights of all men, according to the Declaration of Independence of the United States. What Thomas Jefferson, composer of the original draft, back in 1776, intended by “Happiness” is not totally clear, but he probably had in mind what Inglehart [1] would later call “materialist” values: basically economic and physical security. In those hard times, these goals required strong associations between individuals, based on hierarchy, and on a set of structures (village, church, …), among which was the family, with its undisputed head, and its formal and rigid rules. Individual values (liberty, autonomy, independence, …) did not matter much, then.

Much later, however, and this holds especially for the cohorts born after World War II, economic security led to the emergence, and eventually the predominance, of “post-materialist” values (Fig. 1). This profound change of priorities did not take place abruptly: it followed the renewal of generations because “people are most likely to adopt those values that are consistent with what they have experienced first-hand during their formative years” [2, p. 132], and those who grew up “with the feeling that survival can be taken for granted” attach more importance to such things as autonomy, self-expression, quality of life, freedom of speech, relevance of original ideas, giving people more say in important government decisions, etc”. It is an “aspect of a […] broader process of cultural change that is reshaping the political outlook, religious orientations, gender roles, and sexual mores of advanced industrial society. The emerging orientations place less emphasis on traditional cultural norms” [2, p. 138], and, for what concerns us here, lead to “gender equality… tolerance of outgroups, including foreigners, gays and lesbians [while] younger cohorts become increasingly permissive in their attitudes toward abortion, divorce, extramarital affairs” [2, pp. 139–140]—with the exception of Gardner’s wife, of course.

Cohort analysis: % post-materialists minus % materialists in six west European societies, 1970–2006. Source: Based on combined weighted sample of Eurobarometer surveys and World Values Surveys in West Germany, France Britain, Italy, the Netherlands and Belgium, in given years, using the four-item materialist/post-materialist values [2, p. 135]

Note that this generation-based approach of shifting preferences is not far from Max Planck’s earlier [3, p. 22] and disenchanted opinion that “a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it”. Indeed, Fig. 1 suggests that values and orientations (including prejudices) do not vary much with age, but do evolve with generations—in the case of Fig. 1, towards post-materialist values.

This is the “Silent Revolution”, in Inglehart’s words, which echoes, both in terminology and substance, the “Quiet Revolution” that had taken place in Quebec (CAN), a few years before, in the 1960s. Its most salient features are rapid secularization and the creation of the modern welfare state, whereby health care and education, previously in the hands of the Roman Catholic Church, passed under the responsibility of the provincial government. Here, too, survival could finally be taken for granted, (religious) authority started to dwindle, and new perspectives opened up for individual preferences, in various domains, including family matters.

2 Between Tradition and Rationality

Under the impulse of Gary Becker [4], the New Household Economics (NHE) appeared on the scene, and started to apply the paradigms of economic logic to demography: fertility and the demand for children (where “quantity” is apparently being traded off for “quality”), altruism in the family, intra-household bargaining and gendered division of labour, partnering and re-partnering, and similar topics have been studied under a different light, since then. Basically, the idea now is that all demographic choices are taken after careful examination of the available information, given constraints (in terms of time and money) and personal orientation, with the aim of maximizing some individual utility function. This, to be sure, still leaves a number of important issues open: for instance, how to reconcile the not necessarily converging preferences of various family members, which is definitely more difficult if all have the same rights and are no longer forced to follow the lead of the “household head”, or how to make sure that rational individual choices do not lead to undesirable aggregate outcomes, typically because of externalities, insufficient information or lack a proper system of incentives and disincentives. Fertility is a good example here: individuals may prefer to have too few children (as in most developed countries) or too many (as in sub-Saharan Africa), and the question then arises of how to induce them to have (roughly) the number that is “right” for society—if this ideal number exists at all.

What does the SDT (Second Demographic Transition) theory add to all this? Not much, in our opinion—but the vast echo that it had, and still has, in the specialized literature reveals that demographers worldwide think differently. It shares with the NHE the idea that choices are taken by individuals, and not by institutions (state, church, family, tradition, etc.). But it insists on the importance of the “cultural shift”: once freed from “authority”, individuals do not simply pursue traditional goals with a new rationality; rather, they start to develop personal goals [5], and this explains the increasing variety of (individual) demographic choices, family forms and living arrangements [6, p. 137].

More generally, however, the contrast between the NHE and the SDT theory implicitly refers to a possible opposition between “economics” and “culture”. What is it that (mainly) drives our demographic decisions: is it our personal advantage, that we coldly calculate, or is it the socio-cultural environment, that in part shapes our preferences, and in part forces us along an “expected”, normative path, from which we would like, but do not dare, to deviate for fear of social disapproval? This may apply to de facto unions [7], out-of-wedlock births, frequency of contacts with one’s elderly parents [8], etc. In part, this may be a false problem: internalizion of norms and formation of desires and goals come first, and this is what the SDT theory is about. Once these targets are defined, the problem arises of how to best achieve them, and this is what the NHE deals with. However, with regard to family processes, there are a few assumptions that the NHE and the SDT theory have in common, that are relevant for family formation and dissolution, and that it might be worthwhile to reconsider, at least in part, because they do not seem to be fully consistent with empirical evidence.

3 What Do We Mean by Rational?

“Dynamic economic models are based on the forward looking behavior of economic agents. In the context of life-cycle models, an individual’s consumption and savings decision depends on her subjective beliefs about future interest rates, wage rates and the likelihood of dying. According to these models, individuals have beliefs about such variables and use these beliefs to make decisions today. Until recently common practice in such studies was to assume rational expectations implying that the individuals’ beliefs are given as objective probability distributions. The use of objective distributions is by now put into question by numerous researchers who suggest to directly measure subjective expectations and to evaluate the consequences of deviations of subjective expectations from their objective counterparts” [9].

In other words, people may take their decisions on the basis of false premises. In part, this happens because they do not have enough information, or do not know how to correctly interpret what they know. For instance, when asked about their own future survival prospects, on average “people under-estimate how long they are likely to live by over 5 years. They tend to ignore expected mortality improvements” [10, p. 31]. At the same time, “people are optimistic: they think they will live longer, on average, than people of their own age and sex: by about by 1.19 years (males) and 0.76 years (females).” [10, p. 32]. This may have huge implications on pension policies, for instance: the idea that people know what is best for them, e.g., in terms of age at retirement, is considered almost a tautology, nowadays. But closer inspection reveals that “policy makers … cannot assume that people share a rationale to prepare for a retirement of a realistic length” [11, p. 198].

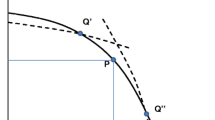

As for couple formation, how else can we interpret the fact the pre-marital cohabitation reduces [12] or, at the very best, does not increase [13] the solidity and the average length of marriages? Partners who have had the opportunity to test each other do not seem to benefit from this experience: why? A possible answer is that interpreting the available information (on the labour market, on the partner, and on a number of other topics) proves too difficult for many, maybe even for the majority of people.

Secondly, people are rarely capable of forecasting the future. If this holds for professional demographers, when they try to anticipate the likely course of populations (i.e., when they do what they should in principle be best equipped to), what else should we expect of common people faced with experiences that are in most cases totally new to them? So, when asked about their pension plans, in a sample of mature Dutch workers, those who think that they will live longer than average also (correctly) state that they intend to retire later. In practice, however, they do not: their age at retirement is just average [14]. The same survey reveals that all the interviewed grossly overestimate their age at retirement, by about 1.6 years, despite the fact that they are all mature workers, aged between 50 and 64, and therefore relatively close to retirement and well aware of the labour market situation, both in general and with reference to their specific case.

It should not come as a surprise, then, that an even greater incapability can be discerned in several other demographic domains, too, closer to our topic of interest. Margolis and Myrskylä [15, p. 48], for instance, conclude that “people seem to poorly predict how children affect their lifestyle and underestimate the costs of children”. On the other hand, assisted reproductive technologies (e.g. artificial insemination, or in-vitro fertilization) are on a spectacular rise, in France (where about 5 % of all births, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, fall in this category) and elsewhere [16]: this happens in part because people are now less prone to accept whatever “God sends” (religious faith is dwindling, remember?), which includes childlessness; in part, because fertility has been delayed so much (age at first birth is now well over 31 years in Italy; [17]) that some women later find it difficult to achieve their desired, even if relatively low, fertility. When it comes to the realization of fertility intentions, less than 50 % of the interviewed, in a Dutch panel, end up exactly with the number of children they had intended to have when they were 26 years old, and this holds especially for women [18].

But incapability of anticipating the future may be only part of the problem. The other part—and this is the third point that we want to make—derives from the fact that people are not consistent in their aspirations, and not on trivial matters only. With regard to childbearing intentions, for instance, Iacovou and Tavares [19, p. 117] agree with Liefbroer that “many people simply change their mind”, typically wanting fewer children later than they did initially, especially after having experienced parenthood, which frequently turns out to be less rewarding than originally imagined (see “incapability of anticipating the future”). Similarly, Testa [20, p. 5] warns that “reproductive ideals and intentions, as well as actual fertility, are developmental by nature and change over the individual’s life course… the adjustments of fertility goals over the life course tend to occur mainly downward in response to different factors and events, one of which is of particular importance, i.e., the transition to a first or a higher birth order child”.

The rise in demand for adopted children that was observed up to a few years ago [21], and that is now being progressively substituted by a demand for medically assisted reproduction (in those countries where this is permitted by law, technology and resources; see again [16]) falls in part in this category, because, up to a certain point at least, it comes from people who had formerly decided not to have children (or had light-heartedly accepted this possibility), but later change their mind.

All the surveys on happiness and life satisfaction consistently show that those who are married are the happiest; then come those who cohabit, then those who are single, and last those who used to live in couple, but are now alone, because of widowhood or marriage breakdown [15,22–25]. Yet, the share of single-person households is everywhere on the rise: in Italy, for instance, up from 9 % in 1901 to almost 30 % now. And it would be even higher, had it not been for immigrants, whose households are typically larger than ours. In part, this depends on a few structural factors, and notably population ageing, but delays in couple formation and increases in divorce and separations, too, play a prominent part. Separations, for instance, are high (almost 30 % of marriages end in a separation, in Italy; between 40 % and 50 % in most of Europe) and on the rise; and couple dissolution is even higher among the cohabiting. Besides, the divorced and the separated, especially when they have children (which happens frequently), also face economic difficulties and time constraints: this increases their stress [26] and is a non-secondary cause of their low levels of happiness. It is not totally clear whether marriage breakdown depends on incapability to interpret the initially available information (on the partner), inability to predict the future (changes in the partner’s traits), or inconsistency (change of preferences). But it is invariably associated with a feeling of failure and loss of confidence (in oneself, in the future, etc.: [23]), which, we contend, is amplified by the fact that the idea that we all proceed by trial and error (error, especially) is not widely accepted, yet. Actually, to the best of our knowledge, it does not even seem to have ever been discussed in the demographic literature.

4 Making and Unmaking Families by “Trial and Error”

If people make mistakes and change their mind, there are all reasons to expect a growing variety of family forms, and strong individual mobility among them—unless, of course, something prevents it: for instance, law provisions, tight social control or lack of economic resources. Indeed, the very notion of marriage has changed over time: the label may be the same, but what was once “until death do us part” is now “until we do us part”. Where is the difference, then, from a simple cohabitation? Everywhere illegitimate children are no longer discriminated (the very term, illegitimate, is now abolished or anyway avoided), and unmarried partners are nowadays entitled to a few (and growing) rights. Breaking a marriage is, of course, more demanding, but the tendency seems to be towards quicker and cheaper solutions, in several (and increasing) cases regulated by prenuptial agreements, where explicit provisions are introduced to regulate the possible termination of marriage.

It is not unlikely that families will eventually become a non-permanent attribute of individuals, with relatively frequent changes in arrangements, partners, houses, etc. Should we worry? Let us rapidly review the potential shortcomings of this evolution. One is that fertility may be (further) depressed by this system of “light” partnering. This is possible, of course, but in the past 25 years fertility has been much lower in southern Europe, with its “strong” families, than in northern Europe, where the system of “modern” families first emerged. Fertility is sustained much more by female empowerment (on the labour market, especially) and active family support (child care facilities, notably) than by prohibition to divorce, or any other constraint.

Children of broken families suffer, and it not easy to guarantee a fair distribution of custodial rights and obligations after couple breakdown. True, but once partners can no longer stand each other, forcing them to remain together may not be the best solution, not even for the children [27]. And if marriage termination is relatively painless for parents (e.g. thanks to prenuptial agreements), why should partners quarrel? This should also ease subsequent cooperation, instead of conflict, in rearing children. Besides, as Leridon [28] suggests, fertility, too, is slowly evolving towards individualization: even without clones, an efficient system of donors (of both sperm and oocytes) will permit individuals to have the children they want, even without partners. If this is indeed the future that awaits us, children of broken couples should not constitute a major problem, especially once they cease to be, and to be considered, an exception. And if Chris Gardner made it, out of his family, why shouldn’t anybody else?

Another possible objection is that families have traditionally been responsible for caring for weak members, e.g. the old and the sick. Who will, if and when families lose their strength? Good question, but let us not forget that this “nurse service” has thus far been provided essentially by women, precisely because of their “lesser” role in society, and in the labour market, and this is no longer going to be the case. It simply means that care costs, thus far largely hidden (and imposed on women) will emerge in full, and will have to be faced, somehow. Not an easy or cheap passage, surely, but so was the abolition of slavery: who would object to it, nowadays?

Finally, and more generally, living in large families generates economies of scale. A future of individuals forming small families, and possibly only for short periods will prove costly. True: but this is already happening. Just as an illustrative example, consider that between 1901 and 2010 the population of Italy almost doubled: the index number is 192 (if 1901 = 100). In terms of equivalence scale, however, costs have increased considerably more: to somewhere between 231, with Carbonaro’s scale [29], and 264, with OECD’s [30] square root scale, precisely because the average family size has shrunk (Figs. 2 and 3). Per capita income has in the meantime increased much more (the index number is close to 2000: see http://www.ggdc.net/MADDISON/oriindex.htm), which simply means that we have decided to use part of our extra riches to buy something that we value (privacy and intimacy), even if it is expensive.

Together with intimacy (see also lines 1–5 of Table 1), we have also bought variety: single parents, unmarried couples and reconstituted families, for instance, are on the rise, although most of these changes can be documented only for the past 20 years or less. There are also indications that constraints, too, and not only choices, play their part: the number of young adults, aged 18–30, who still live with their parents, and are therefore classified as “children” in population surveys (Table 1), and whose growing share depends in large part on the unfavourable labour market conditions of this age group [32].

The family is changing in Italy, and probably also elsewhere, and it has evolved from an institution to an individual attribute. Within the limits imposed by the respect of other’s needs, and by personal resources, and unless major structural changes occur, this “Quiet Revolution”, which has only just begun, will most likely continue. Individuals will thus be left to themselves in their “pursuit of happiness”, but, in the process, mistakes, changes of opinion and direction, disappointments and costs, of all kind, will be the rule rather than the exception.

References

Inglehart, R.: The silent revolution in Europe: intergenerational change in post-industrial societies. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 65(4), 991–1017 (1971)

Inglehart, R.: Changing values among western publics from 1970 to 2006. West Eur. Polit. 31(1–2), 130–146 (2008)

Planck, M.: Scientific Autobiography and Other Papers. New York 1949 (original edition 1948. As cited in T.S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions)

Becker, G.S.: A Treatise on the Family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1981)

Sobotka, T.: The diverse faces of the second demographic transition in Europe. Demogr. Res. 19(8), 171–224 (2008)

De Rose, A., Vignoli, D.: Families “all’italiana”: 150 years of history. Riv. It. Di Econ. Demogr. E Stat. 65(2), 121–144 (2011)

Di Giulio, P., Rosina, A.: Intergenerational family ties and the diffusion of cohabitation in Italy. Demogr. Res. 16(14), 441–468 (2007)

Bordone, V.: Social norms and intergenerational relationships. In: De Santis, G. (ed.) The Family, the Market or the State?, pp. 159–178. Springer, Dordrecht (2012). doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4339-7

Ludwigy, A., Zimperz, A.: A parsimonious model of subjective life expectancy. WP 74, Econ. Res. S. Afr. (2008)

O’Brien, C., Fenn, P., Diacon, S.: How long do people expect to live? Results and implications. Centre for Risk and Insur. Stud. Res. Report 2005–1. Nottingham Un Business School (2005)

O’Connell, A.: How long do we expect to live? Popul. Ageing 4, 185–201 (2011)

Berrington, A., Diamond, I.: Marital dissolution among the 1958 British birth cohort: the role of cohabitation. Popul. Stud. 53(1), 19–38 (1999)

Impicciatore, R., Billari, F.: Secularization, union formation practices, and marital stability: evidence from Italy. Eur. J. Popul. 28(2), online first (2012)

van Solinge, H., Henkens, K.: Living longer, working longer? The impact of subjective life expectancy on retirement intentions and behaviour. Eur. J. Public Health 20(1), 47–51 (2010)

Margolis, R., Myrskylä, M.: A global perspective on happiness and fertility. Popul. Dev. Rev. 37(1), 29–56 (2011)

de La Rochebrochard, É.: Assistance médicale à la procréation (AMP). Dictionnaire de démographie (dir. par F. Meslé, L. Toulemont et J. Véron) (2011)

De Rose, A., Salvini, S.: Rapporto sulla popolazione. Il Mulino, Bologna (2011)

Liefbroer, A.C.: Changes in family size intentions across young adulthood: a life-course perspective. Eur. J. Popul. 25(4), 363–386 (2009)

Iacovou, M., Tavares, L.P.: Yearning, learning and conceding: reasons men and women change their childbearing intentions. Popul. Dev. Rev. 37(1), 89–123 (2011)

Testa, M.R.: Family sizes in Europe: evidence from the 2011 Eurobarometer survey. Eur. Demogr. Res. Paper 2 (2012)

UN: Child Adoptions: Trends and Policies. New York (2009)

Kohler, H.P., Behrman, J.R., Skytthe, A.: Partner + children = happiness? The effects of partnerships and fertility on well-being. Popul. Dev. Rev. 31(3), 407–445 (2005)

Rivellini, G., Rosina, A., Sironi, E.: Marital disruption and subjective well-being: evidence from an Italian panel survey. Paper of the 46th SIS Scientific Meeting, Rome (2012)

Verbakel, E.: Subjective well-being by partnership status and its dependence on the normative climate. Eur. J. Popul. 28(2), online first (2012)

Zimmermann, A.C., Easterlin, R.A.: Happily ever after? Cohabitation, marriage, divorce and happiness in Germany. Popul. Dev. Rev. 32(3), 511–528 (2006)

Aassve, A., Betti, G., Mazzuco, S., Mencarini, L.: Marital disruption and economic well-being: a comparative analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series A 170(3), 781–799 (2007)

Piketty, T.: The impact of divorce on school performance : evidence from France, 1968–2002, CEPR discussion paper series no 4146 (2003)

Leridon, H.: La famille va-t-elle disparaître ? in Dictionnaire de démographie (dir. par F. Meslé, L. Toulemont et J. Véron) 164–166 (2011)

Istat: La povertà in Italia. Anno 2010 (2011)

OECD: What are equivalence scales? Paris (2008)

Istat: La misurazione delle tipologie familiari nelle indagini di popolazione. Metodi e norme 46 (2010)

Schizzerotto, A., Trivellato, U., Sartor, N.(a.c.d.).: Generazioni disuguali. Le condizioni di vita dei giovani di ieri e di oggi: un confronto. Il Mulino, Bologna (2011)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

De Santis, G., Salvini, S. (2016). Do Rational Choices Guide Family Formation and Dissolution in Italy?. In: Alleva, G., Giommi, A. (eds) Topics in Theoretical and Applied Statistics. Studies in Theoretical and Applied Statistics(). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27274-0_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27274-0_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-27272-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-27274-0

eBook Packages: Mathematics and StatisticsMathematics and Statistics (R0)