Abstract

There is currently a great deal of variation in the assessment terminology used by researchers and educators alike. Consistency of vocabulary is necessary for productive dialogue to occur between professionals. Well-defined assessment terminology contributes significantly to how educators and researchers conceptualise, and subsequently implement assessment processes. A brief history of assessment terminology is explored to provide a clearer comprehension of how our current understanding of assessment has been influenced. Using a cyclical model of assessment modified from previous work by Wiliam and Black, Harlen, and the Alberta Assessment Consortium, the authors define both assessment and evaluation and then proceed to further explore the various purposes and functions of assessment. Bidirectionality of feedback between external organisational-driven assessment and internal student-driven assessment is discussed as being essential to maintaining the formative intent of assessment while simultaneously meeting accountability needs. Other assessment terms are finally explored in the framework of these discussions.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Assessment

- Evaluation

- Nature of assessment

- Nature of evaluation

- Educational terminology

- Purpose of assessment

- Purpose of evaluation

- Function of assessment

- Function of evaluation

- Formative assessment

- Summative assessment

- Assessment for learning

- Assessment of learning

- Assessment as learning

- Defining assessment and evaluation

1 Educational Renovations: Nailing Down Terminology in Assessment

Over the past two decades there has been a radical shift in educators’ views of assessment and evaluation . At first glance it seems as though assessment and evaluation concepts ought to be straightforward, and yet when examined microscopically the intricate interconnectedness of sustaining systems becomes readily apparent. The 1990s saw a profound shift in focus from summative to formative assessment, and both theorists and practitioners became more concerned with validity and authenticity issues in the classroom (Black, 1993; Dassa, Vazquez-Abad, & Ajar, 1993; Daws & Singh, 1996; Haney, 1991; Maeroff, 1991; Meyer, 1992; Newmann, Secada, & Wehlage, 1995; Perrenoud, 1991; Rothman, 1990; Sadler, 1989; Sutton, 1995; Wiggins, 1993; Wiliam & Black, 1996; Willis, 1990). Shifting conceptualisations of assessment have caused the educational equivalent of the demolition phase of a renovation, yet current frameworks designed to replace their predecessors “perpetuate an understanding which is confused and illogical” (Taras, 2008b, p. 175). Indeed, running the term “assessment” through the ERIC database alone revealed tens of thousands of articles to review, with each scholar choosing to focus on a different aspect of evaluation or assessment and disagreement on the theoretical frameworks of assessment proliferating. Although the segmentation of assessment into differing purposes has provided helpful information and could contribute significantly to a strong, cohesive model, such a coherent theoretical framework remains to be established. Unless the different segments begin to coalesce into a unified picture of what evaluation and assessment are, educational dialogue will continue to be confused and progress towards better classroom practice will be inhibited.

Consistent definitions of terminology pertaining to classroom assessment are lacking (Frey & Schmitt, 2007). Taras (2008b) concurred with this conclusion, noting the lack of alignment in formative and summative definitions and their relationship to each other, as well as theoretical gaps resulting in a divergence between theory and practice (2008a). In 2008, Gallagher and Worth (2008) certainly observed differences in definition and interpretation among merely five states in the United States of America that were examined in their research. Understanding assessment terminology and its framework is essential not only for intelligent dialogue among researchers and teachers (Frey & Schmitt, 2007), but also it is important for discourse with educational leadership and policy makers (Broadfoot & Black, 2004; Taras, 2008b) and for the research quality and subsequent empirical evidence outlining best practices in formative assessment (Dunn & Mulvenon, 2009). Consequently, the intent of this article is to dissect the concepts of assessment and evaluation in an attempt to create both an educational understanding of related terminology and a framework of the interconnected system we call assessment.

2 History of Assessment

Warmington and Rouse (1956) cite the earliest known recorded assessment term as “test”, provided by Socrates as he explained the need for testing to Glaucon in order to establish the highest echelon of Guardians:

[W]e must examine who are best guardians of their resolution that they must do whatever they think from time to time to be best for the city. They must be watched from childhood up; we must set them tests in which a man would be most likely to forget such a resolution or to be deceived, and we must choose the one who remembers well and is not easily deceived, and reject the rest. (p. 213)

This example is the first documented indication of humans making the assumption that knowledge and ability are measurable attributes. Uninfluenced by Socrates’ philosophies, the Chinese had similar ideas somewhat later and what would now be termed “performance assessment” (see later in this article for further discussion) formed the basis of Chinese civil examinations possibly as early as approximately 200 years BCE (Frey & Schmitt, 2007). In 1200 AD, the first doctoral examination was conducted in Italy at the University of Bologna, and marked the first instance of academic measurement in Western civilization (Linden & Linden, 1968). Five hundred years later this practice reached the Master degree level at Cambridge University in England. It was not until the early 1800s that performance-based methods of examination were used in common schooling practices at lower educational levels (Frey & Schmitt, 2007).

Although tests of performance have been used for centuries, Francis Galton was the first to attempt the scientific development of mental tests in the 1870s, and Binet carried out similar research in the early 1900s (Berlak et al., 1992; Eisner, 1985). Even though the Thorndike Handwriting Scale was successfully produced and implemented in 1909 specifically for school use, and was followed by a number of achievement and aptitude tests (Perrone, 1991), World War I provided the perfect opportunity to capitalize on the research by Galton and Binet by testing potential soldiers’ mental skill and aptitude. As a result of military drafts, Robert Yerkes found himself chairing a committee intended to devise a group intelligence test (Yoakum & Yerkes, 1920). After much debate, persuasion, and tireless research the Army Alpha and Army Beta tests were spawned – largely based on the research of Binet and A.S. Otis from Stanford University. The objective of examination procedures was initially to increase efficiency of military operations; however, the impact these tests had on both military operations and later educational uses (such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test [SAT]) forever changed the face of assessment (Black, 2001). With the adaptation of standardised testing for educational purposes, large-scale summative assessments and multiple-choice response formats became the testing methods of choice – chiefly because they were highly efficient and cost-effective when assessing large groups of people from a diversity of geographical regions.

Despite the negative consequences and drawbacks of this form of testing (often called traditional assessment), the time-efficient ease of the tests’ administration, scoring, and interpretation minimised financial costs and thus caused it to survive in the face of heavy criticism.

In the late 1960s Scriven (1967) began writing about what he termed “formative” and “summative evaluation”. Originally Scriven shared his thoughts about formative and summative evaluation with the intention that these terms be applied to programme evaluation ; however, he quickly broadened his focus to include educational practices as well. Wiliam and Black (1996) noted that Bloom, Hastings, and Madaus (1971) were the first to extend the terms “formative” and “summative” to the currently understood and accepted educational uses of the terms. As Wiliam and Black (2003) carefully relayed, the purposes behind the forms of assessment were most important.

Madaus and Dwyer (1999) noted the return of performance assessment in the early 1980s, around the same time as authentic assessment was possibly first referenced (likely by Archbald and Newman (1988) according to Frey and Schmitt 2007). Similarly, the term “alternative assessment” was also brandished in the 1980s possibly first by Murphy and Torrance in 1988 (Buhagiar, 2007). As a method of authentic evaluation, portfolio assessment was later detailed by Sulzby (1990) and then further elaborated by Bauer (1993). Most recently Perie, Marion, and Gong (2009) have added to Wiliam and Black’s (1996) concept of formative and summative assessment by detailing a third intermediary that they label “interim assessment”, and in addition to this there appears to be a resurgence in the study and application of “dynamic assessment” (e.g., Crick, 2007; Poehner & Lantolf, 2005, 2010; Yeomans, 2008). Somewhere along the way many of the aforementioned terms began to be used interchangeably and connoted different meanings to different people. The intent of the next three sections is therefore to explore the often-confused terms of assessment and evaluation in the hope of clarifying discrepancies.

3 Assessment Versus Evaluation

Quite often when reading articles on assessment and/or evaluation, it seemed as if the terms assessment and evaluation were used either interchangeably or were distinctly defined and separated from one another. For example, Scriven (1967) described what most educators and researchers today would call assessment, yet he refers to it as evaluation. Savickiene (2011) uses the term “evaluation” in much the same way as Scriven; however, she refers to evaluation as the process of making a decision based on assessment data, while assessment is the “collection, classification, and analysis of data on student learning achievements” (p. 75). Taras (2005) noted the common use of the terms assessment and evaluation; however, she distinguished between the two concepts by using “‘assessment’ … to refer to judgements of students’ work, and ‘evaluation’ to refer to judgements regarding courses or course delivery, or the process of making such judgements” (p. 467). Hosp and Ardoin (2008) utilise much the same definitions of assessment and evaluation as Taras. Similarly, Harlen (2007) used assessment in a manner that focused on students while evaluation was used to refer to the aspects of education that did not directly affect or refer to student achievement. In contrast to Taras and Harlen, Trevisan (2007) used the terms differently by referring to the purpose of “evaluability assessment” as assessing readiness for evaluation whereas “evaluation” (specifically programme evaluation ) was portrayed as having a greater sense of finality. More recently Dunn and Mulvenon (2009) have suggested that it is most helpful to separate formative assessment and formative evaluation by an object-use paradigm where a formative assessment is the test and an evaluation speaks to the use of data. The aforementioned articles highlight the terminology confusion that results largely from semantic discrepancies and confusion of method, use, and purpose. With such disparity, how do we create a common consensus on terminology that is both straightforward and practical? Although arriving at such unanimity is no small feat, perhaps it is most helpful to turn to Paul Black and his various associated counterparts for further clarification. As one of the leading authorities in assessment with at least 49 publications in the field, his contributions arguably reframed the way we view assessment today.

In educational circles the concepts that Trevisan (2007) discussed as assessment and evaluation are often referred to as formative and summative assessment respectively – terminology brought to prominence by Black (1993). According to Black and Wiliam (2003), the distinction between formative and summative assessment lies primarily in the function of the assessment, with formative assessments narrowing the gap between a student’s current versus expected knowledge (also referred to as assessment for learning ), and summative assessments providing a description of a student’s performance without providing opportunity for further learning (referred to also as assessment of learning) . Wiliam and Black (1996) conceptualised summative and formative assessment as being linked and simply on opposite ends of a continuum; however, significantly the process of assessment itself was viewed as cyclical in nature. Irving, Harris, and Peterson (2011) attribute this cycle to an interplay between what they term “assessment and feedback” (p. 415); however, in the context of this article the terminology we apply to the same concepts would be evaluation and communication as being the two key propellants in the assessment cycle.

Although copious numbers of articles have been written surrounding formative assessment and its distinction from summative assessment, Taras (2005) pointed out that researchers may have lost Scriven’s original vision of bringing the dimension of formative assessment to educators’ attention in their haste to distinguish between formative and summative assessment. Indeed Taras noted that the separation between formative and summative assessment “has been self-destructive and self-defeating” (p. 476). Despite her strong position about separating formative and summative assessment completely, Taras (2007) later points out difficulties that arise because formative and summative assessments lack differentiation in the assessment literature, yet what if the two were never intended to be separated? Perhaps the following argument oversimplifies the issue; however, if researchers return to the fundamental nature and purposes of assessment and of evaluation it is possible that the issue may be clarified further.

4 Nature of Assessment and Evaluation

The Oxford English Dictionary defined evaluation as “the making of a judgement about the amount, number, or value of something; assessment”. When reading this description, two concepts that arose were: (a) a sense of exacting a judgment (possibly numerical and value laden), and (b) an atmosphere of finality to the verdict reached. A process to reach such a judgment is implicated; however, the focus appears to be on a conclusive outcome. Interestingly, the finality of what is termed “evaluation” parallels common conceptions of what is labelled summative assessment. For example, Taras (2005) described summative assessment as “a judgment which encapsulates all the evidence up to a given point” (p. 468). It seems that the terms “evaluation” (Trevisan, 2007) and “summative assessment” (Taras, 2005; Wiliam & Black, 1996) are both referring to a similar concept and have been used interchangeably. Even the perceptions of educators were that summative assessment had an air of finality or an end point (Taras, 2008b).

Illustrating the difficulty in distinguishing between assessment and evaluation, the Oxford Dictionary defines assessment as: “the evaluation or estimation of the nature, quality, or ability of someone or something”. Confusion arises largely from the interchangeability of the terms and their use to define one another, yet definitions and descriptions of assessment in educational research describe assessment in a manner altered from the Oxford Dictionary definition. Harlen (2006) described assessment as “deciding, collecting and making judgments about evidence relating to the goals of the learning being assessed” (p. 103). This explanation fits with Wiliam and Black’s (1996) portrayal of the assessment cycle, which consists of (a) eliciting evidence (deciding what evidence is desired and how it can best be obtained and observed), and (b) interpretation (decoding the information that has been obtained as a result of elicitation, and taking action based on this understanding). More recently, Taras (2008b) affirmed perceptions that assessment is more than making a judgment, and involves a cyclical process with “formative and summative assessment feed[ing] into each other” (p. 183). Based on the work of Wiliam and Black, Harlen, and a cyclical model of assessment put forth by the Alberta Assessment Consortium (2005), we would like to suggest the following cyclical stages of assessment:

-

deciding what information is desired, how best to obtain such information, and what will indicate learning has taken place (planning);

-

actively eliciting desired information (elicitation);

-

interpreting the data (interpretation);

-

making a judgment based on one’s interpretation (evaluation);

-

communicating this interpretation (communication); and

-

deciding what the next steps in learning should be (reflection).

Evaluation still involves judgment; however, it implies action to improve learning by providing feedback and opportunity for reflection, which both influence the planning phase of the next revolution in the cycle (see Fig. 2.1).

Inherently cyclical (Harlen, 2000; Wiliam & Black, 1996), it is the nature of assessment that clarifies the relationship between assessment and evaluation. If assessment is viewed as a cyclical process and evaluation is viewed merely as a stage in this sequence, then the philosophical implication is that learning is continuous, lifelong, and does not have a definitive endpoint. For example, Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall, and Wiliam (2004), Stiggins and Chappuis (2005), and Taras (2009) highlight a shift in educational practices to use summative assessments in formative ways – illustrating a desire for all assessment to contain some formative aspects despite alternate purposes. Kealey (2010) uses the term “feedback loop” to describe this concept in her review for social work education and assessment, and Segers, Dochy, and Gijbels (2010) describe it as a feedback and feedforward loop that ultimately results in what they term “pure assessment”. An advantage to viewing the relationship between assessment and evaluation in this manner is that the neutrality of the oft-disparaged summative assessment has the potential to be restored as it would no longer be viewed with the same finality; rather, summative assessment could be viewed as a higher order cyclical process that feeds both educational administration and student learning needs. Wehlburg (2007) captures the spirit of continuity in assessment by describing an “assessment spiral” (p. 1) in which each cycle of assessment is monitored and increased in its quality. Cyclical models have already been suggested for use with students on Individual Education Programs (IEPs) (Thomson, Bachor, & Thomson, 2002), implemented in engineering education programs (Christoforou & Yigit, 2008), and are recommended when applied to regular classroom assessment as well (Alberta Assessment Consortium, 2005). Viewing assessment and evaluation in a cyclical framework removes the need for distinction between assessment and evaluation: there is simply assessment albeit assessment with varying purposes.

5 Definitions of Assessment and Evaluation

Having addressed the nature of assessment, we now move on to developing concise definitions of assessment and evaluation. For the purposes of this chapter, assessment is defined as: a cyclical learning process of planning, elicitation, interpretation, evaluation, communication, and reflection. Notice that this definition is not specific to student achievement as this definition can be used not only for students, but also for teachers, schools, and even workplace assessments. With the definition of assessment in mind, evaluation is defined as: a stage in the assessment cycle characterised by making a judgment about learning based on an interpretation of elicited information.

Although these definitions address continual attempts to distinguish between assessment and evaluation, they fail to address the spirit that lies behind such attempts – namely, the purposes of assessment . Therefore, the next section attempts to construct a theoretical framework that uses our definitions, yet also addresses concerns of purpose or function.

6 Function Versus Purpose of Assessment

Further characterisation of the assessment process is made possible by exploring the purpose of assessment. Taras (2007) points out that the terms “purpose” and “function” are used interchangeably; however, upon examination subtle differences exist that distinguish between the purpose of assessment and its function. Newton (2007) lists the difficulties in assessment purpose as being primarily those of definition and of use categorisation. While he links purpose chiefly to the decision level of assessment (and therefore to the use to which assessment is applied), further reflection challenges this conclusion. It seems as though what Newton labels as purpose, is actually function, evidenced by the following quotation:

This [the decision level] is taken to be the most significant usage of the term “assessment purpose” since it seems to be the level that is most frequently associated with it in the technical literature. For this reason, and for the sake of clarity, if the term “purpose” is to be retained as a feature of assessment discourse – as it will be in the remainder of this paper – it ought to be restricted to the decision level. (p. 150)

For the sake of clarity, in this chapter when we refer to the purpose of assessment we are describing why the assessment was performed, while function describes how the assessment is used in order to meet the established purpose. This distinction will be expanded upon in the following two sections.

7 Purposes of Assessment

Ultimately the primary purpose of assessment is to enhance learning. Beneficiaries of learning may vary; however, learning ideally is the focus of all assessment. In 2006, the Western and Northern Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Education (WNCP) put forth a document that summarised three purposes of assessment, namely, (a) Assessment for Learning, (b) Assessment as Learning, and (c) Assessment of Learning. Although we will deviate slightly from the descriptions in the WNCP, these concepts provide the most helpful basis on which to form a discussion on purpose and so we now turn to them.

7.1 Assessment for Learning

The term “assessment for learning” is often used interchangeably with “formative assessment” as is evidenced by both Black and Wiliam’s (2006) chapter surrounding formative assessment practices entitled “Assessment for Learning in the Classroom” and Harlen’s (2006) stated use of the terms. According to Harlen, what matters most is not the kind of assessment used, but the purpose of its use. Black and Wiliam’s reflections capture the learning-focused purpose of formative assessment while providing details on the process of assessment and its constructivist nature. Taras (2010) disagrees and clarifies that regardless of how the work is used, “the process of formative assessment can only be said to have taken place when feedback has been used to improve the work” (p. 3021). She feels that formative assessment (or assessment for learning) is a process of the interplay between what she refers to as summative assessment and feedback – yet when she is referring to summative assessment, she is referring specifically to the fact that a judgment must be made about learning and knowledge, much the same as the stage of evaluation in our cycle. It may be most helpful to thus conceptualise assessment for learning as embodying the primary purpose of assessment (the enhancement of learning), yet primarily as the general process of assessment enacted or supported by other purposes of assessment such as assessment of learning or summative assessment. As all assessment ought to be for learning, it is hoped the necessity for the use of this terminology will eventually be antiquated.

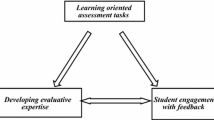

7.2 Assessment as Learning

Assessment as learning is formative in nature; however, it specifically refers to the task of metacognitive learning. Overall, the general aim of assessment as learning is to eventually bridge and shift ownership of learning from the teacher to the student – in other words from external to internal monitoring. Salient examples of assessment as learning include elements of what Boekaerts and Corno (2005) and Clark (2012) discuss as self-regulated learning and what Brookhart (2001) describes as student self-assessment. Boekaerts and Corno paint a portrait of a self-regulating student as follows: “All theorists assume that students who self-regulate their learning are engaged actively and constructively in a process of meaning generation and that they adapt their thoughts, feelings, and actions as needed to affect their learning and motivation” (p. 201).

Although they explore student self-regulation in far more depth than we are able to capture here, this description beautifully portrays the intent of assessment as learning. In the words of Black and Wiliam (1998), “the ultimate user of assessment information that is elicited in order to improve learning is the pupil” (p. 142). For this reason, assessment as learning is of crucial importance to student outcomes because it engages students, motivates them, and supports eventual transition to lifelong learner.

7.3 Assessment of Learning

Assessment of learning is often used as another label for summative assessment. Under the assumption that all assessment ought to be formative in nature (i.e., assessment for learning), does assessment of learning still deserve to be a purpose of assessment? In its traditional role, assessment of learning was used primarily for both political and educational decision making, thus connoting a large degree of control over students (Taras, 2008a). There has therefore been an outcry against summative assessment in general, particularly as a result of both perceived and actual misuse – despite research suggesting that large-scale summative assessments are still a necessity (Brookhart, 2013). Newton (2007) pointed out that in the manner that the term “summative” is used it has no purpose and only characterises a type of judgment. The truth inherent in this statement lies in a traditionally problematic approach to assessment that either interrupted the assessment cycle at the evaluation stage or shuffled the information to external organisational agencies without feedback returned to the student. As Taras (2008b) dissects this issue, she draws attention to the fact that judgments are naturally occurring and necessary, albeit sometimes misused. Yet if approached properly, assessment of learning can be a valuable tool to summarise a collection of assessment cycle rotations. Conceptualise it as a geological core sample that communicates a student’s learning over a period of time. It accomplishes on a macroscale what occurs on a microcosmic level in the classroom all the time. When used appropriately, this feedback can provide a student with a greater sense of accomplishment, at an organisational level can provide learning opportunities for teachers and administrators concerning how to support further student learning; and at a political/societal level can provide potential information that, when used correctly can contribute to vital decision making processes.

8 Functions of Assessment

One of the most helpful descriptions of assessment function comes from Newton (2007). Although Newton used the term “purpose”, we argue that he is really addressing assessment “function” (how an assessment is used), and helpfully provides a list of various functions of assessments. Perhaps first and foremost, an important aspect of this chapter is that there may be both student and organisational uses of assessment. Newton’s use of learning classifications of formative, placement, diagnosis, guidance, and student monitoring are all examples of student-focused functions of assessment. Harlen (2005) would use the term “internal” (p. 208) to refer to a similar concept (she used it specifically when dealing with formative and summative assessment; however, we find the language use helpful for our purposes so forgive the license taken here). Returning to Newton, institution monitoring, resource allocation, organisational intervention, system monitoring, and comparability illustrate the conjoint functions of organisational assessment. Borrowing from Harlen, we will use the term “external” to describe this as well. Distinguishing between the two fundamental functions and describing potential uses within these frameworks is helpful insofar as it points toward the primary directional flow of information while still challenging educators and administrators to keep as much bidirectional flow as possible (see Fig. 2.2).

Depending on the desired function of assessment , the exchange of information between cycles may occur at different points in the cycle. Figure 2.2 is intended to illustrate the bidirectional flow of information in assessment practices where External Organizational Driven Assessment (EODA) involvement is necessary; however, it is not to be assumed that this is always the case, and there may be instances of Internal Student Driven Assessment (ISDA) independent cycling. Ultimately, for EODA to be used in a formative manner there must be effective and helpful feedback into the ISDA assessment cycle. For some examples of lower order assessment functions (modified and extended from Newton, 2007) as well as the primary cycle in which they operate, see Fig. 2.3.

There are many aspects of Fig. 2.3 that are worthy of note. Although organisational intervention, system monitoring, institution monitoring, and resource allocation affect students, direct student learning is not as much a priority for these functions. Conversely, although EODA involvement may play a role in guidance, diagnostic, placement, student monitoring, and selection functions, less bidirectional flow of information is required for these functions than those categorised as both ISDA and EODA. Although this is a rough division of various functions and certainly not intended as an exhaustive list, it is hoped it will provide a springboard for further discussion and debate .

9 Conceptualising Other Terminology

As alluded to in the beginning of this chapter, there is an excessive number of terms brandished about without a reliable level of comprehension among researchers. Although we have already focused on many such terms, we feel it is beneficial to explore a few in our discussion.

9.1 Authentic Assessment

The term “authentic assessment” speaks not so much to the purpose of assessment as to its contributions to quality and validity. “Alternative assessment”, “direct assessment”, or “performance assessment ” are sometimes used interchangeably with the term “authentic assessment” (National Center for Fair and Open Testing, 1992); however, this can be understandably confusing and it can be helpful to reconceptualise the relationship between these terms based on nature, purpose, and function.

Instead of viewing “authentic assessment” as a separate type of assessment, it seems logical that authentic is used as an adjective. Segers et al. (2010) helpfully outline four criteria for an assessment to be authentic: representativeness (adequately assessing the scope of the domain at stake); meaningfulness (“assessing relevant and worthwhile contributions of the learner,” [p. 200]); cognitive complexity (higher order skills present); and content coverage (breadth of material included). When viewing “authentic assessment” in this light, it is possible for a wide variety of assessment tools and processes to be authentic.

Perhaps the best way to facilitate comprehension of authentic assessment is to provide a practical example of an authentic assessment scenario that might unfold in any classroom. Following is a brief depiction of an authentic assessment in a Junior High Language Arts classroom.

Ms Woods would like to teach her students the components of a short story as well as encourage their ability to apply this knowledge to their own writing. She decides that ultimately the most authentic way to teach such knowledge and skill is to have the students write a short story; however, she feels they should be involved in the assessment process as well so that they can truly understand what they are supposed to be learning and doing. Ms Woods begins by dividing up the various parts of a short story and using cooperative learning groups to have the students teach each other about the various components. Once the class has learned about the various segments, then she lays before them the task of writing a short story themselves and helps them brainstorm rubric requirements by which the short story will be marked as well as their participation in the editing process with their classmates. After this process has been completed the final drafts of their stories will be placed in their portfolios and they will complete further self-evaluation at the end of the term.

In this example, the scope of the assessment is aligned with what Ms Woods wishes to assess, the activity is meaningful in the respect that learners are contributing their thoughts at a number of different levels in a variety of ways, there is good cognitive complexity, and the content coverage is appropriate for the desired outcome. Because these four criteria are satisfied, it can be said that this assessment activity is authentic .

9.2 Alternative Assessment

Similarly, “alternative assessment” is a term of description that simply refers to approaching student-driven assessment in a manner that is different than that which has traditionally been done – usually in reference to strict pencil-and-paper testing. Stobart and Gipps (2010) outline three levels of alternative assessment that refer to different facets or applications of the word “alternative”. Firstly they describe “alternative assessment” in the context of alternative formats. An alternative format could include administering a test on computer instead of by paper-and-pencil (with the content and scope remaining entirely the same) or it could refer to the use of open-ended written-response questions in contrast to traditional strictly multiple-choice examinations. Alternative formats are seen as the most basic level of alternative assessment. Secondly, Stobart and Gipps described alternative models of assessment. When referring to alternative models of assessment, they described simply the use of a different approach to assessment including examples of “performance assessment ” and alternative educational assessment (including extended projects/assignments, “portfolio assessment”, and assessments by teachers for external purposes). Finally Stobart and Gipps addressed alternative purposes of assessment – referring to the use of assessment for formative and diagnostic purposes as an alternative to a focus only on summative assessment. Formative and diagnostic purposes are thought to dovetail with one another as diagnostic assessment identifies learner knowledge that is currently present and gaps that are present between current and desired understanding of material, while formative assessment seeks to close gaps and increase learning primarily through the use of feedback. “Dynamic assessment” was seen to be an alternative form of “diagnostic assessment” based on the sociocultural theories of Vygotsky (1978) which uses a one-to-one learner-facilitator model which focuses on how effectively students learn when assisted. (See the sections on diagnostic and dynamic assessment later in this article for more information on these areas.)

In addition to the simple distinction of “alternative assessment” as being something other than what was traditionally done, it is also helpful to examine the assumptions made by an alternative assessment as they prove useful in further delineating the concept of “alternative assessment”. Anderson (1998) pointed out that alternative assessment assumes that:

-

there are multiple meanings of knowledge;

-

learning is actively constructed;

-

process and product are paramount;

-

inquiry is central;

-

there is a focus on multimodal abilities;

-

it is subjective;

-

power and control of learning is shared by the teacher and the student – it is a collaborative process; and

-

the primary purpose is to facilitate learning.

Note the consistency of these assumptions with the assessment terminology described by Stobart and Gipps (2010). Such characteristics also fit nicely with Newton’s (2007) descriptions of various uses of assessment, and the view of learning as a central focus of assessment.

9.3 Diagnostic Assessment

Turner, VanderHeide, and Fynewever (2011) discuss diagnostic assessment in a similar manner as we would discuss a summative assessment used for a formative purpose. They distinguish diagnostic assessment from summative assessment by pointing out that a diagnostic assessment is used in a formative fashion while a summative assessment is used as a summary at the end of instruction. While this contributes to the furthering of utilising summative assessment for formative purposes, this description is contrary to the definitions supported in this article and as such we are not considering this as helpful for our purposes. Instead, when discussing diagnostic assessment we are referring primarily to assessment streamlined to describe cognitive functioning in students. Diagnostic assessment is performed with the underlying purposes of (a) providing information so that instruction can be altered and student learning improved, as well as (b) providing students with greater insight so that they can maximise their strengths and support any areas of weakness they may have. Its use is intervention-focused and less frequently employed than other forms of assessment (Newton, 2007). For our purposes, diagnostic uses are typically both student-centred and organisationally focused because feedback is provided and used in both spheres. Diagnostic assessments are intended to be repeated periodically so that the feedback may be used to streamline student instruction, optimise student-learning potential, and to provide a certain level of accountability at an organisational level.

9.4 Dynamic Assessment

Dynamic assessment outlines a certain methodological and philosophical approach to assessment defined as the “dialectical unity of instruction and assessment” by Poehner and Lantolf (2010). Based on Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development (Leung, 2007), dynamic assessment is a social constructionist form of assessment that is “both retrospective (diagnostic and reflective) and prospective (formative and motivational)” (Crick, 2007, p. 139). The basic premises for dynamic assessment are that the social environment is key to development (Poehner, 2008), intelligence is a product of both biological predisposition and social construction (Yeomans, 2008), and that supportive interactions or interventions with others foster learning (Leung, 2007; Yeomans, 2008). It implies a specific interaction between the person assessing and the person being assessed, with particular attention paid to a type of scaffolding interaction that is based within – sometimes described as a “test-train-test design” (DÖrfler, Golke, & Artelt, 2009). In this model feedback is very important, particularly when it is detailed and learning-oriented. Also common in dynamic assessment is the concept of collaboration between peers in a more group-based than individually-based form of assessment. In practical terms, dynamic assessment describes a specific interplay between student and teacher/mediator whereby the cycle of assessment is navigated by both parties in a predominantly metacognitive fashion.

9.5 Self-Assessment and Integrative Assessment

While the implementation of self-assessment follows the same cycle as regular assessment, the student is placed in the role of assessor and follows a specific self-assessment subcycle. Self-assessment in reality speaks not to a new form of assessment, but rather it specifies who is performing the act of assessment. More specifically, McMillan and Hearn (2008) define self-assessment as “a process by which students (1) monitor and evaluate the quality of their thinking and behavior when learning, and (2) identify strategies that improve their understanding and skills” (p. 40). According to McMillan and Hearn, self-assessment is described as a formative use of assessment involving a cyclical process of identifying learning targets and instructional correctives, self-monitoring, and self-judgment.

In their interview study of teachers in Canada, Volante and Beckett (2011) suggested that in order for self-assessment to be valuable as a formative use of assessment, students must understand both the aims of the assessment and the criteria for assessment. The inherent value of having students engage in their own assessment is explored in detail by Brookhart (2001); however, generally speaking self-assessment is a vital tool used to meet the purpose of assessment as learning.

Another term used somewhat interchangeably with self-assessment is “integrative assessment”. Crisp (2012) discusses the two primary purposes of integrative assessment as being to enhance students’ learning approaches in the future and to reward them for their growth and insight in their approach to learning in contrast to the actual learning itself. It would be this use of assessment in which students would actively participate in the structuring of the task itself, thus encouraging students to take responsibility for their own learning. Crisp’s description of integrative assessment fits well with current definitions of self-assessment; however, self-assessment at present seems to be a term more commonly used than integrative assessment.

9.6 Self-Evaluation

Based on our discussion of assessment and evaluation, this term is unnecessary. Self-evaluation does not speak to a new type of assessment, it simply points out who is performing the evaluation phase of assessment, which is already specified if using the term “self-assessment”.

Although there are more terms that are used in respect to assessment and evaluation, they cannot all be covered due to space constraints. Still, the basic case has been woven and the groundwork of a foundation for conceptualisation of terms has been built. Perhaps most important is that we are conscious of being specific not only in the use of the assessment terms, but also in describing:

-

their particular purpose and function(s);

-

who is performing the assessment or evaluation;

-

who or what is being assessed or evaluated; and

-

the process that was followed to reach assessment conclusions.

10 Conclusion

The purpose of this chapter is to encourage more specific use of our language and to promote common understanding as educators and researchers; hence, we have attempted to advance an awareness of the following:

-

the cyclical nature of assessment creating a spiral formation of learning;

-

evaluation as a component of assessment;

-

the various purposes and functions of assessment;

-

the importance of authenticity in assessment as it contributes to validity ;

-

the integral role feedback plays in assessment;

-

the formative nature of assessment; and

-

the flow of information between Internal Student Driven Assessment and External Organizational Driven Assessment cycles.

Such common understandings as these allow educators to better address the needs of students and be more purposeful in assessment design and implementation. In addition, these concepts serve as primary considerations when establishing an assessment model in a school as well as for establishing policies regarding general school assessments and accountability measures. In an evidence-based society, it is imperative that educators not only strive to increase learning and communicate outcomes, but also ensure that what we are encouraging and communicating is reliable and valid. If we clarify our dialogue and can create methods of assessment that are specific to the function for which they were intended, validity will be further promoted and the value of educational systems will be made more apparent.

References

Alberta Assessment Consortium. (2005). A framework for student assessment (2nd ed.). Retrieved from: http://www.aac.ab.ca/framework_blue.html

Anderson, R. S. (1998). Why talk about different ways to grade? The shift from traditional assessment to alternative assessment. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 74, 5–16.

Archbald, D. A., & Newmann, F. M. (1988). Beyond standardized testing: Assessing authentic academic achievement in the secondary school. Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Assessment. (2010). OxfordDictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from: http://oxforddictionaries.com/view/entry/m_en_us1223361

Bauer, N. J. (1993, April). Instructional designs, portfolios and the pursuit of authentic assessment. Paper presented at the spring conference of the New York State Association of Teacher Educators, Syracuse, NY.

Berlak, H., Newmann, F. M., Adams, E., Archbald, D. A., Burgess, T., Raven, J., et al. (1992). Toward a new science of educational testing and assessment. New York, NY: SUNY.

Black, P. (1993). Formative and summative assessment by teachers. Studies in Science Education, 21(1), 49–97.

Black, P. (2001). Dreams, strategies and systems: Portraits of assessment past, present and future. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 8(1), 65–85.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2004). Working inside the black box: Assessment for learning in the classroom. Phi Delta Kappan, 86, 8–21.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139–148.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2003). In praise of educational research: Formative assessment. British Educational Research Journal, 29, 623–637.

Black, P., & William, D. (2006). Assessment for learning in the classroom. In J. Gardner (Ed.), Assessment and learning (pp. 9–26). London, UK: Sage Publications.

Bloom, B. S., Hastings, J. T., & Madaus, G. F. (1971). Handbook on formative and summative evaluation of student learning. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Boekaerts, M., & Corno, L. (2005). Self-regulation in the classroom: A perspective on assessment and intervention. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54(2), 199–231.

Broadfoot, P., & Black, P. (2004). Redefining assessment? The first ten years of assessment in education. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 11(1), 7–27.

Brookhart, S. M. (2001). Successful students’ formative and summative uses of assessment information. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 8(2), 153–169.

Brookhart, S. M. (2013). The use of teacher judgement for summative assessment in the USA. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 20(1), 69–90.

Buhagiar, M. A. (2007). Classroom assessment within the alternative assessment paradigm: Revisiting the territory. The Curriculum Journal, 18(1), 39–56.

Christoforou, A. P., & Yigit, A. S. (2008). Improving teaching and learning in engineering education through a continuous assessment process. European Journal of Engineering Education, 33(1), 105–116.

Clark, I. (2012). Formative assessment: Assessment is for self-regulated learning. Educational Psychological Review, 24, 205–249.

Crick, R. D. (2007). Learning how to learn: The dynamic assessment of learning power. Curriculum Journal, 18(2), 135–153.

Crisp, G. T. (2012). Integrative assessment: Reframing assessment practice for current and future learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(1), 33–43.

Dassa, C., Vazquez-Abad, J., & Ajar, D. (1993). Formative assessment in a classroom setting: From practice to computer innovations. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 39, 116.

Daws, N., & Singh, B. (1996). Formative assessment: To what extent is its potential to enhance pupils’ science being realized? School Science Review, 77, 99.

DÖrfler, T., Golke, S., & Artelt, C. (2009). Dynamic assessment and its potential for the assessment of reading competence. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 35, 77–82.

Dunn, K. E., & Mulvenon, S. W. (2009). A critical review of the research on formative assessment: The limited scientific evidence of the impact of formative assessment in education. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 14(7), 1–11. Retrieved from: http://pareonline.net/pdf/v14n7.pdf.

Eisner, E. W. (1985). The art of educational evaluation. Philadelphia, PA: Falmer Press.

Evaluation. (2010). OxfordDictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from: http://oxforddictionaries.com/view/entry/m_en_us1417730

Frey, B. B., & Schmitt, V. L. (2007). Coming to terms with classroom assessment. Journal of Advanced Academics, 18(3), 402–423.

Gallagher, C., & Worth, P. (2008). Formative assessment policies, programs, and practices in the southwest region (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2008–No. 041). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest. Retrieved from: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/projects/project.asp?ProjectID = 150.

Haney, W. (Ed.). (1991). We must take care: Fitting assessments to function. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Harlen, W. (2000). Teaching, learning and assessing science (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Harlen, W. (2005). Teachers’ summative practices and assessment for learning: Tensions and synergies. Curriculum Journal, 16(2), 207–223.

Harlen, W. (2006). On the relationship between assessment for formative and summative purposes. In J. Gardner (Ed.), Assessment and learning (pp. 103–117). London, UK: Sage.

Harlen, W. (2007). Criteria for evaluating systems for student assessment. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 33, 15–28.

Hosp, J. L., & Ardoin, S. P. (2008). Assessment for instructional planning. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 33, 69–77.

Irving, S. E., Harris, L. R., & Peterson, E. R. (2011). ‘One assessment doesn’t serve all the purposes or does it?’ New Zealand teachers describe assessment and feedback. Asia Pacific Education Review, 12, 413–426.

Kealey, E. (2010). Assessment and evaluation in social work education: Formative and summative approaches. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 30, 64–74.

Leung, C. (2007). Dynamic assessment: Assessment for and as teaching? Language Assessment Quarterly, 4(3), 257–278.

Linden, J. D., & Linden, K. W. (1968). Tests on trial. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Madaus, G. F., & Dwyer, L. M. (1999). Short history of performance assessment: Lessons learned. Phi Delta Kappan, 80, 688–695.

Maeroff, G. I. (1991). Assessing alternative assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 73(4), 273–281.

McMillan, J. H., & Hearn, J. (2008). Student self-assessment: The key to stronger student motivation and higher achievement. Educational Horizons, 87(1), 40–49.

Meyer, C. A. (1992). What’s the difference between authentic and performance assessment? Educational Leadership, 49(8), 39–40.

Murphy, R., & Torrance, H. (1988). The changing face of educational assessment. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press.

National Center for Fair and Open Testing. (1992). What is authentic evaluation? Cambridge, MA: Author.

Newmann, F. M., Secada, W. G., & Wehlage, G. G. (1995). A guide to authentic instruction and assessment: Vision, standards and scoring. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Center for Education Research.

Newton, P. E. (2007). Clarifying the purposes of educational assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 14(2), 149–170.

Perie, M., Marion, S., & Gong, B. (2009). Moving toward a comprehensive assessment system: A framework for considering interim assessments. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 28(3), 5–13.

Perrenoud, P. (1991). Towards a pragmatic approach to formative evaluation. In P. Weston (Ed.), Assessment of pupils’ achievement: Motivation and school success (p. 92). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Swets and Zeitlinger.

Perrone, V. (1991). ACEI position paper on standardized testing (Available from the Association for Childhood Educational International, 17904 Georgia Ave, Suite 215, Olney, Maryland 20832). Retrieved from: http://uee.uabc.mx/valora/infoEvaluacion/criticaapruebas.pdf

Poehner, M. E. (2008). Dynamic assessment: A Vygotskian approach to understanding and promoting L2 development. New York, NY: Springer.

Poehner, M. E., & Lantolf, J. P. (2005). Dynamic assessment in the language classroom. Language Teaching Research, 9(3), 233–265.

Poehner, M. E., & Lantolf, J. P. (2010). Vygotsky’s teaching-assessment dialectic and L2 education: The case for dynamic assessment. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 17(4), 312–330.

Rothman, R. (1990). New tests based on performance raise questions. Education Week, 10(2), 1.

Sadler, R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18, 119–144.

Savickiene, I. (2011). Designing of student learning achievement evaluation. Quality of Higher Education, 8, 74–93.

Scriven, M. (1967). The methodology of evaluation. In R. Tyler, R. Gagne, & M. Scriven (Eds.), Perspectives of curriculum evaluation (pp. 39–83). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Segers, M., Dochy, F., & Gijbels, D. (2010). Impact of assessment on students’ learning strategies and implications for judging assessment quality. In P. Peterson, E. Baker, & B. McGaw (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (3rd ed., pp. 196–201). Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

Stiggins, R. J., & Chappuis, S. (2005). Putting testing in perspective: It’s for learning. Principal Leadership, 6(2), 16–20.

Stobart, G., & Gipps, C. (2010). Alternative assessment. In B. McGraw, E. Baker, & P. Peterson (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (3rd ed., pp. 202–208). Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

Sulzby, E. (1990). Qualities of a school district culture that support a dynamic process of assessment. In J. A. Roderick (Ed.), Context-responsive approaches to assessing children’s language (pp. 97–104). Urbana, IL: National Conference on Research in English.

Sutton, R. (1995). Assessment for learning. Salford, UK: RS.

Taras, M. (2005). Assessment – Summative and formative – Some theoretical reflections. British Journal of Educational Studies, 53(4), 466–478.

Taras, M. (2007). Machinations of assessment: Metaphors, myths and realities. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 15(1), 55–69.

Taras, M. (2008a). Assessment for learning: Sectarian divisions of terminology and concepts. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 32(4), 389–397.

Taras, M. (2008b). Summative and formative assessment: Perceptions and realities. Active Learning in Higher Education, 9(2), 172–192.

Taras, M. (2009). Summative assessment: The missing link for formative assessment. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 33(1), 57–69.

Taras, M. (2010). Assessment for learning: Assessing the theory and evidence. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2, 3015–3022.

Thomson, K., Bachor, D., & Thomson, G. (2002). The development of individualised educational programmes using a decision-making model. British Journal of Special Education, 29(1), 37–43.

Trevisan, M. S. (2007). Evaluability assessment from 1986 to 2006. American Journal of Evaluation, 28(3), 290–303.

Turner, M., VanderHeide, K., & Fynewever, H. (2011). Motivations for and barriers to the implementation of diagnostic assessment practices – A case study. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 12, 142–157.

Volante, L., & Beckett, D. (2011). Formative assessment and the contemporary classroom: Synergies and tensions between research and practice. Canadian Journal of Education, 34(2), 239–255.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Warmington, E. H., & Rouse, P. G. (1956). Great dialogues of Plato. Toronto, ON, Canada: The New English Library.

Wehlburg, C. M. (2007). Closing the feedback loop is not enough: The assessment spiral. Assessment Update, 19(2), 1–2, 15.

Western and Northern Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Education. (2006). Rethinking classroom assessment with purpose in mind: Assessment for learning, assessment as learning, assessment of learning. Retrieved from: http://www.wncp.ca/media/40539/rethink.pdf

Wiggins, G. P. (1993). Assessment: Authenticity, context, and validity. Phi Delta Kappan, 75(3), 200–214.

Wiliam, D., & Black, P. (1996). Meanings and consequences: A basis for distinguishing formative and summative functions of assessment. British Educational Research Journal, 22, 537–548.

Wiliam, D., & Black, P. (2003). In praise of educational research: Formative assessment. British Educational Research Journal, 29, 623–637.

Willis, S. (1990). Transforming the test. ASCD update. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 32(7), 3–6.

Yeomans, J. (2008). Dynamic assessment practice: Some suggestions for ensuring follow-up. Educational Psychology in Practice, 24(2), 105–114.

Yoakum, C. S., & Yerkes, R. M. (1920). Army mental tests. New York, NY: Holt.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

McKean, M., Aitken, E.N. (2016). Educational Renovations: Nailing Down Terminology in Assessment. In: Scott, S., Scott, D., Webber, C. (eds) Leadership of Assessment, Inclusion, and Learning. The Enabling Power of Assessment, vol 3. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23347-5_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23347-5_2

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-23346-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-23347-5

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)