Abstract

The article draws from 199 sources on assessment, learning, and motivation to present a detailed decomposition of the values, theories, and goals of formative assessment. This article will discuss the extent to which formative feedback actualizes and reinforces self-regulated learning (SRL) strategies among students. Theoreticians agree that SRL is predictive of improved academic outcomes and motivation because students acquire the adaptive and autonomous learning characteristics required for an enhanced engagement with the learning process and subsequent successful performance. The theory of formative assessment is found to be a unifying theory of instruction, which guides practice and improves the learning process by developing SRL strategies among learners. In a postmodern era characterized by rapid technical and scientific advance and obsolescence, there is a growing emphasis on the acquisition of learning strategies which people may rely on across the entire span of their life. Research consistently finds that the self-regulation of cognitive and affective states supports the drive for lifelong learning by: enhancing the motivational disposition to learn, enriching reasoning, refining meta-cognitive skills, and improving performance outcomes. The specific purposes of the article are to provide practitioners, administrators and policy-makers with: (a) an account of the very extensive conceptual territory that is the ‘theory of formative assessment’ and (b) how the goals of formative feedback operate to reveal recondite learning processes, thereby reinforcing SRL strategies which support learning, improve outcomes and actualize the drive for lifelong learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Overview

The paper advances the proposition that the theory and practice of formative assessment combines cognition, social, and cultural theories which guide instructional methods and drive self-regulated strategies and lifelong learning competences among learners. The first section, ‘An Introduction to the Learning Community’, presents the basic objectives for the theory of formative assessment and briefly relates how that framework actualizes self-regulated learning (SRL). The second discusses the post-structuralist foundation for the theory of formative assessment. It has been written in accordance with Alexander’s (2008) observation that research is migrating “farther and farther from the initial philosophical or psychological roots” (p. 370). Therefore, it is essential to secure an early understanding of the philosophical essence from which the theory arises and to locate that essence in a relevant contemporary socio-political context. The third section discusses the major elements of feedback (formative, synchronous, and internal) which, when taken together form the core of formative assessment. Each aspect has a powerful influence over the development of the meta-cognitive functioning and the self-efficacy required for individuals to make progress in their mastery of SRL strategies. As we move to the ‘center’ of the paper, the fourth main section, ‘Formative Assessment: Assessment Is for Self-Regulated Learning’ speaks to the central thesis of the article. The section discusses how formative assessment differs from other forms of assessment and how those differences drive SRL. The second purpose of the section is to discuss the confusion and controversy surrounding the term and how, when it is misappropriated it loses all potential to develop SRL strategies among learners. Finally, this section delineates SRL and draws parallels between formative assessment and SRL as a dynamic which emphasizes active participation and recognizes the pivotal importance of feedback. The fifth section, ‘Connecting Objectives, Goals and Strategies’ details the goals of formative assessment before connecting them to the strategies deployed by students as they move along the SRL continuum toward autonomy. The sixth section ‘Internalization, Environment, Interaction, and Experience’ argues for a harmonious conception of formative assessment, one which does not engage with the traditional theoretical tensions between ‘intellectual tribes’. It is reasoned that for SRL to take place these four key ‘factors of knowledge production’ should be understood by practitioners, administrators, and policy-makers. An analysis of literature on vicarious and participatory aspects of the theory of formative assessment are given emphasis in the seventh section: ‘Theoretical Synthesis: Indirect and Direct Learning’, because as learners become more skillful self-regulators they interact with the environment in various ways in order to access the informaton they need to achieve their personal and social goals. The eighth section, ‘Socially Mediated SRL: the Circulation of Discursive Power’ discusses mutual learning relationships, emphasizing the role of sociocultural theories in enhancing understanding of what the social and environmental aspects of the formative assessment classroom should look like if learners are to gain mastery of SRL. The final main section, ‘Thematic Discussion’ arises from previous philosophical and theoretical sections directly and discusses six interrelated themes of global interest on formative assessment and SRL: (1) lifelong learning, (2) self-efficacy, (3) collective efficacy, (4) persistence and stable motivation, (5) achievement, and (6) feedback and meta-cognition.

The research databases ERIC and PsychInfo were searched between 1975 and 2011 using the following terms: formative assessment, feedback, self-regulated learning, SRL, meta-cognition, Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), social context, sociocultural, lifelong learning, collective efficacy, self-efficacy, achievement, motivation and autonomy. Studies were chosen for their potential to contribute to a comprehensive theory for SRL. Of particular interest are studies which permit the comparison and contrast between differing nations which have implemented formative assessments into their policy frameworks. As such, the seminal Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report ‘Formative Assessment: Improving Learning in Secondary Classrooms’ (2005) and the proceedings of the follow up international conference ‘Assessment for learning: Formative Assessment’ (2008) are used as steering papers which serve to guide the selection of the research presented in this paper.

Contribution to the Field

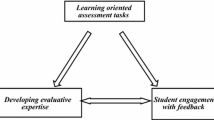

Figure 1 represents the theory of formative assessment by expressing the outer ring as the philosophical basis (PS) from which the theory of formative assessment (TFA) arises. The diagram presents a theoretical delineation of the theory of formative assessment, explaining the ‘encapsulation’ of SRL through the pursuit of objectives and goals (AaL, AfL, G1…G8), which arise from SCT and sociocultural theories and therefore brings SRL into existence. It should be noted that the objectives of Assessment as Learning (AaL) and Assessment for Learning (AfL) have each been refined into four goals (G5 to G8 and G1 to G4, respectively) to which they relate and which are pursuant of SRL. Moving toward the core of the cross-section one encounters the meta-cognitive (MC) components of planning (P), monitoring (M), and reflection (R) and the affective (SE) components of ambition (A), effort (E), and persistence (Pe) required for SRL to exist. Feedback (F) is located at the center of the model. Feedback is pivotal to formative assessment and therefore to the development of SRL strategies among students. The elements presented in Fig. 1 will be discussed in a depth which expresses the dynamic nature of the figure and brings new clarity to the theory of formative assessment and stimulate new directions in research and practice.

The theory of formative assessment in cross-section. PS post-structuralism, TFA Theory of Formative Assessment, SCT & SC Socio-Cognitive Theory and Sociocultural theories, AaL assessment as learning, AfL assessment for learning, G1..G8 formative goals 1..8, SRL self-regulated learning, MC meta-cognition, SE self-efficacy, P planning, M monitoring, R reflecting, A ambition, E effort, Pe persistence, F feedback

An Introduction to the Learning Community

Assessment ‘for’ and ‘as’ learning

Formative assessment is connected by two contiguous assessment objectives: assessment for learning (AfL) and assessment as learning (AaL). The purpose of AfL is to monitor the progress of the learner toward a desired goal, seeking to close the gap between a learner’s current status and the desired outcome. “This can be achieved through processes such as sharing criteria with learners, effective questioning and feedback” (Assessment Action Group/AiFL Programme Management Group [AAG/APMG], 2002–2008). AaL refers to the collaborative and individual reflection on evidence of learning. It is a process “where pupils and staff set learning goals, share learning intentions and success criteria, and evaluate their learning through dialogue and self and peer assessment” (AAG/APMG, 2002–2008). Through a process of frequent community participation, learners move along a continuum of self-regulation as they acquire the skills to use learning and assessment tools [externally fabricated assessments] and eventually the technological expertise that characterizes membership in the culture as toolmakers able to co-construct learning and assessments tools (cf. Lave and Wenger). Rogoff (2003) refers to the development of expertise through guided experience as development through participation in cultural activities. As Schön (1987) states, “as she learns to design, she learns to learn to design—that is, she learns the practice of the practicum,” (p. 102).

Philosophical origins

The essence of formative assessment arises from interpretations of post-structuralism based upon a principled assimilation of work by a diverse range of theorists (cf. Foucault, Bourdieu and Heidegger). Heidegger (1889–1976) saw a need for the reinvention of a society in which education plays a central role by establishing “an edifying, empowering and liberating reconnection to the world” (Thomson 2004, p. 458). Dewey (1938) is well-known for his critical evaluations on the environmental structuring found in most schools where desks are arranged in rows and students are reinforced for silence and compliance. Dewey’s concerns that such methods diminish the individual curiosity to learn parallel the influential post-structuralism of Heidegger, who also recognized the challenge to authentic individuality in a world which emphasizes conformity. Dewey’s critique leads to the first of two philosophical strands most relevant to the post-structuralist basis of formative assessment. One strand is the transformation of passive recipients into the active participants, who create and contribute their own meanings instead of phlegmatically receiving meanings and leaving them unquestioned. The second strand is the rebuff of ‘scientism’. Scientism (e.g., as embodied in the No Child Left Behind Act [NCLB], 2002 in the US) posits that standardized testing offers a scientific and therefore superior method of measuring the quality of public schools and teacher competence. Advocates of NCLB believe that high scores on standardized tests equate to a successful learning experience including quality instruction. This is a belief widely challenged as specious because the focus on high-stakes testing trivializes learning and threatens the internal states (e.g., confidence, self-efficacy, and interest) required for the self-regulation of learning (Shepard 2000; Abrams 2007). These values underpins the need for active participation emphasized by studies on SRL and the more specific aspects of social context captured by sociocultural research which informs the theory of formative assessment. There are five additional aspects of post-structuralist thought which are elemental to understanding the theory of formative assessment: (1) the examination of the democratic values of equality, representation, and consensus; (2) the recognition that it is the difference between individuals which create opportunities for social development by discourse; (3) it is discourse which determines how power is circulated throughout a society; (4) it is those with knowledge who have the power to determine the nature and subject of the discourse; and (5) the advocacy for viewpoints which challenge the existing order. Drawing from the post-structuralist values of representation, discourse, control, and consensus, the instructional techniques found in the formative assessment classroom reduce the formality and psychological risk associated with teacher-fronted transmission methods, the use of which negate the benefits associated with collaborative learning. The values inherent to post-structuralism set the stage for the development of SRL strategies among students. Despite the evident benefits of SRL, field research (e.g., Black and Wiliam 2006; Macintyre et al. 2007) has found that the circulation of discursive and procedural ‘power’ among students made teachers in the US (and elsewhere) feel insecure, due to a certainty in their minds that the move toward spontaneous dialogue would not actualize the legitimate learning relationships predicted by formative assessment research, instead fomenting disruptive social behavior among students. A contrasting conception of dialogue is provided by the Danish Folkeskole (public primary and lower secondary school system), which implements formative assessment in order to produce self-regulated and informed students. Townshend et al. (2005) explain the Danish system as one in which, “open dialogue and exchange between and among students and teachers are considered essential to education, and reinforce the Danish model of democracy” (p. 117). The Danish philosophy on assessment provides an interesting counterpoint to the American emphasis on standardized assessment procedures because in Denmark verbal communication is by far the most important means for collecting holistic evidence about students’ learning experiences. Townshend et al. (2005) explain that in Denmark, “oral, rather than written, assessment is preferred because it is quick and flexible and permits students to initiate or respond to teachers. In this way it is possible to detect and correct misunderstandings and ambiguities on a timely basis” (p. 120).

Aspects of Feedback: Formative, Synchronous, and Internal

The aforementioned philosophical essence determines the value that teachers, administrators, and policy-makers place upon discourse, identity, and social power (taken together the term ‘voice’ seems appropriate). The notion of ‘voice’ impacts on how teachers structure learning interactions or feedback with and among students. Effective feedback, which forms the core of formative assessment practice and SRL, (see Fig. 1) occurs when learners are encouraged to articulate their tacit knowledge (existing motives, ideas, opinions, beliefs, and knowledgeable skills). In their Finnish study, Voogt and Kasurien (2005) emphasize the importance of tacit knowledge, “Formative assessment may consist of hard data, but more often and more importantly of ‘tacit knowledge’, i.e. knowledge that both the teacher and student obtain through discussion, reflection and experience” (p. 154).

It is clear that an important function of the “formative interaction” (Black and Wiliam 2009, p. 11) is to make the experiential tacit knowledge that is ‘hidden’ within the learner transparent, explicit and available (cf. Polanyi). Matthew and Sternberg (2009) emphasize that tacit knowledge is “deeply rooted in action and context, and can be acquired without awareness and is typically not articulated or communicated” (p. 530). In the formative classroom, tacit knowledge is made explicit and accessible through active participation and mutual discourse. McInerney (2002) suggests that the process of making learners’ knowledge visible should not be one of “extract[ing] knowledge from within…to create new explicit knowledge artifacts”. Instead, organizations should make tacit knowledge explicit by focusing on the creation of a “knowledge culture” that encourages learning and the creation and sharing of knowledge (p. 1014; cf. Black and Wiliam). The second contention—tacit knowledge is both an outcome of experience-based learning and as a basis for continuous learning—is an important understanding that logically arises from the experiential acquisition of knowledge. The connection between experiential (tacit) knowledge and the internalization of new knowledge is discussed in detail later in this paper and is a central theme in SRL as emphasized in the Japanese literature on organizational innovation (Nonaka 1994; Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995); applied to US military and university settings (Matthew and Sternberg 2009) and as a key feature of global professional practice (Sternberg and Horvath 1999). While the literature on tacit knowledge typically arises from adult vocational settings, the theory of formative assessment applies the notion of a “knowledge culture” to schools and younger learners. This approach decreases the external risks and increases the intrinsic benefits learners associate with their learning environment; the circumstances required for learners to move toward a mastery of SRL strategies. There are three aspects of feedback which when taken account of have the potential to impact meta-cognitive and affective (self-efficacious) functioning, revealing otherwise recondite knowledge among learners which facilitate the acquisition of SRL strategies. They are discussed in three sub-sections: formative feedback; synchronous feedback, and external/internal feedback.

Formative feedback

For Black and Wiliam (2009)

A formative interaction is one in which an interactive situation influences cognition, i.e., it is an interaction between external stimulus and feedback, and internal production by the individual learner which involves looking at the three aspects, the external, the internal and their interactions. (p. 11).

Therefore, sharing learning intentions and identifying clear assessment criteria is the sine qua non of formative assessment (Black et al. 2003; Mansell et al. 2009). The objective of formative feedback is the deep involvement of students in meta-cognitive strategies such as personal goal-planning, monitoring, and reflection, which support SRL by giving learners “the power to oversee and steer one’s own learning so that one can become a more committed, responsible and effective learner” (Black and Jones 2006 p. 8). Looney et al. (2005) conducted research in two Italian secondary schools. By the third year of school, students in Italy are expected to have developed a relatively high level of autonomy, social skills and the ability to make functional decisions regarding their own development. The researchers took a progression approach by gathering evidence for the validity of formative assessment to promote SRL from the students. The respondents were generally positive about their experience of school and:

…provided some evidence that they are indeed learning to be autonomous. As one Year 3 student declared, if she does not understand a new concept, she tries to relate it to another subject in order to understand the context better, or its relation to other ideas. In other words, she develops her own learning scheme. Ultimately, this student said, “It is up to us to learn”. This sentiment was widely echoed among fellow students. (p. 66)

This view is consistent with post-structuralist philosophy in that empowering feedback is circulated among the students, which then makes learning objectives and the “features of excellent performance” transparent (Shepard 2000 p. 11). Cauley and McMillan (2010, p. 3) observe that such practices “encourage students and give them a greater sense of ownership in instructional activities”, elaborating that collaborative goal setting improves students’ intrinsic motivation and, when combined with other formative assessment practices, also further supports the adoption of mastery goals. The need for transparent grading criteria and learning goals is emphasized by Frederiksen and Collins (1989) in their critique of summative tests which “subvert” teaching and lead to an emphasis on the memorization of facts and rote sequences at the expense of reasoning skills.

Feedback is described by Winne and Butler (1994) as, “information with which a learner can confirm, add to, and overwrite, tune, or restructure information in memory, whether that information is domain knowledge, meta-cognitive knowledge, beliefs about self and tasks, or cognitive tactics and strategies” (p. 5740). Nicol and MacFarlane-Dick (2006) argue that formative feedback should be used to empower students as self-regulated learners, and contend that because formative feedback strategies enhance self-regulation all assessments should be restructured as formative assessments (Sadler 1989; Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick 2006). Butler and Winne (1995) underscore the centrality of feedback in regulating learning progression, “for all self-regulated activities, feedback is an inherent catalyst,” (p. 246). It is worthy of note that not everything that teachers believe to be feedback is in fact formative. For example, Hattie and Temperley (2007) contribute to the corpus of understanding on feedback as a powerful instructional approach in their meta-study which derived effect sizes for different kinds of feedback. They obtain high effect sizes when students are given ‘formative feedback’; that is, feedback on how to perform a task more effectively and far lower effect sizes when students are given praise, rewards, or punishment. Simply telling a student to ‘work harder’ or ‘recalculate your answer’ does not possess the qualities of formative feedback or promote self-regulated learning because it does not strategically guide (or scaffold) learning by informing the student how or why they need to do this. Feedback becomes formative when the evidence of learning is used to adapt teaching to meet student needs (Black and Wiliam 1998b; Sadler 1989). More specifically, students are provided with instruction or thoughtful questioning which scaffolds further inquiry and deepens cognitive processing. This instructional approach closes the gap between their current level of understanding and the desired learning goal (Vygotsky 1978; 1987). This mutual process of continual readjustment causes learning to progress at a rate which is sufficient to motivate students to self-regulate the effort required to progress further (Butler and Winne 1995). The discursive landscape is punctuated by three question categories, each of which is formative and self-regulatory in nature: (a) Feed-up: Where are we going? This concerns itself with the sharing of learning objectives; (b) Feedback: How are we doing? A question which monitors and assesses learning progression, either for a specific task or more generally; (c) Feed-forward: Where to next? This question relates to the next steps required for improvement on a specific task/project or more generally across time (Hattie and Temperley 2007).

The theory of formative assessment hinges on the strategic adaptation of instruction to meet student needs. This entails collaborative activity between adults and children as mutual partners who share responsibility and play different roles (Dewey 1938; Black and Wiliam 1998a; ARG 1999; Black and Wiliam 2009). Dewey (1938) emphasized it was the responsibility of an adult to prepare a child for participation in multiple communities by guiding children without controlling them. Crossouard (2011) studied the impact of formative assessment on students from socially deprived areas of Scotland. The study emphasized the notion of teacher “positionality”; that teachers should model forms of discourse which support the description of assessment criteria in a socioculturally responsible way and meet the needs of the students (cf. Black and Wiliam). McCombs (1989) notes that self-regulation is not a ‘fixed personality trait’, and students can be taught to consciously manage their learning environment, by blending social strategies with personal strategies in order to improve their academic learning and achieve performance goals. Recent developments at the Italian Ministry of Education (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca) have led to the enrichment of classroom instruction by a monitoring process designed to shape the conscious regulation of the learning experience. Teachers follow the development of students’ personal and social strategies carefully by tracking:

…each student’s overall level of maturation, including their ability to respect rules, to establish good relationships with peers and teachers, and to engage in learning and to contribute to the class. Teachers also follow the development of students’ autonomy (including their ability to organize themselves and develop good work habits), attention in class, ability to comprehend and analyze information, and to make links between subject areas. (Looney et al. 2005, p. 172).

Synchronous feedback

Black and Wiliam (2009) distinguish formative assessment from an overall theory of instruction and connect it to SRL when they explain, “it is clear that formative assessment is concerned with the creation of, and capitalization upon, “moments of contingency” in instruction for the purpose of the regulation of learning processes” (p. 10). The development of a ‘moment’ into a genuine opportunity for learning is dependent on the meta-cognitive awareness of students’ and the self-belief that their efforts will result in success (self-efficacy). Of particular relevance is ‘reflection-in-action’; that blend of monitoring and reflection which together permit the reshaping of that being worked on while working on it (Schön 1987; Harrison et al. 2003; Kuiper and Pesut 2004). Black and Wiliam incline toward using metaphor from electrical engineering (e.g., the ‘black box’). Once again similar metaphor is employed to emphasize that these moments of contingency can be either synchronous or asynchronous.

Synchronous feedback is an important process as teachers strive to instill SRL characteristics among their students. Activities which allow students to get immediate feedback and respond actively are highly engaging; an important reason for the popularity of computer games (Malone and Lepper 1987 as cited in Brophy 2004, p. 197). Synchronous feedback has been found to enhance learning (Dihoff et al. 2004), be more effective at supporting higher psychological functioning, such as synthesis (Maddox et al. 2003; Maddox and Ing 2005). Teachers and students need to become accustomed to verbal interactions which are mutual. This means that they work together to creat the ‘moment’ and which remain focused on the task yet divergent and flexible enough to fully capitalize on the ‘moment of contingency’. Schön (1987) describes the dialogue between interactants as: “questioning, answering, adjusting, listening, demonstrating, observing, imitating, criticizing—all are chained together so that one intervention or response can trigger or build on another” (p. 114). Black and Wiliam (2009) characterize the inherent spontaneity of formative dialogue as, “a formidable problem for teachers” (p. 13). Formidable because it: (a) exposes teachers to the many ways in which students argue, evaluate and synthesize information for problem solving purposes and (b) it often requires a radical change in their instructional approach (Black and Wiliam 2006; Black and Wiliam 2009). Whatever the challenges may be, the purpose of formative assessment is to elicit the encoded (or perhaps better understood as ‘recoded’) information from students and make it meta-cognitively accessible, that is to say—visible as assessment information.

Feedback is asynchronous when any of the following three conditions apply: (a) there is a time interval between gathering the evidence and sharing the evidence; (b) a time interval before gathering and sharing the evidence; or (c) the evidence has been synthesized from historical analysis. In the case first condition, asynchronous feedback may be evidence gathered from homework and used the next day. The second condition is similar, but for the need to wait for the lesson to end before the students share their understandings, which are used to plan the next lesson. The third condition includes the use of long-range asynchronous use of insights gained from students’ stable misconceptions from previous years. In summary, if formative feedback is not embedded in the micro-genesis of verbal interaction then it is asynchronous because it meets one of the conditions stated above. Asynchronous feedback performs a useful function, permitting reflection on its use and it is often more comprehensive and permanently recorded assessment evidence. For example, recent research from the UAE, (Mehmet 2010) used “pedagogical documentation”, described as “a formative assessment technique and instructional intervention designed to increase student learning by recording children’s experiences” (p. 1439). The impact of recording students’ learning experiences was found to have “the potential to improve children’s learning, contribute to teachers’ awareness of learning processes and help parents gain a better understanding of learning processes in their children’s education” (p. 1439).

Internal and external feedback

Internally generated feedback is inherent to engagement and regulation. Formative assessment has the potential to reveal the internal and therefore recondite psychological and affective aspects of the learning process. Formative assessment is therefore a powerful action research methodology for the daily use of classroom teachers. The combination of meta-cognitive demands and supportive social context explains why it is a widely acknowledged process which enhances student motivation and achievement (Sadler 1989; Black and Wiliam 1998a, b; Irving 2007; Cauley and McMillan 2010). Formative assessments are specifically aimed at generating feedback, both internal and external which inform learners how to progress learning and meet standards (Sadler 1989). In the context of formative assessment and SRL, Chinn and Brewer’s (1993) review indicates that considering feedback merely in terms of the information it contains is too simplistic. The decoding, encoding, and retrieval of meaning cannot be reduced to a superficial analysis of semiotic ‘content’, delivered like a parcel to a mailbox. Accordingly, Corner (1983) remarks that the encoding and decoding of information “are socially contingent practices which may be in a greater or lesser degree of alignment in relation to each other but which are certainly not to be thought of… as ‘sending’ and ‘receiving’ linked by the conveyance of a ‘message’ which is the exclusive vehicle of meaning” (p. 267–8). Students interpret external feedback according to reasonably stable beliefs concerning subject areas, learning processes, and the products of learning. Butler and Winne (1995) observe that, “student beliefs about their learning experience influence the generation of internal feedback” (p. 254). Butler and Winne (1995) contend that learners use formative feedback to monitor their engagement with tasks and the key meta-cognitive process of monitoring generates internal feedback. Self-regulated learners differ from their non-self-regulated peers by generating more internal feedback, responding positively to external feedback, and increasing efforts to achieve learning goals (Bose and Rengel 2009). External feedback may, “confirm, add to, or conflict with the learner’s interpretations of the task and the path of learning” (Butler and Winne 1995, p. 248). Students’ tacit knowledge (experiences, beliefs, opinions) influences the processing of externally provided feedback and may even distort the message that feedback is intended to carry (cf. Corner 1983). Individuals differ in the sensitivity of self-reactive judgment to external feedback which impact on conation. Conation (from the Latin conatus, in English ‘effort’) is of particular importance when considering the internal states of learners. Conation is synonymous with self-efficacy, referring to the personal, intentional, planful [sic], deliberate, goal-oriented, or striving component of motivation, the proactive (as opposed to reactive or habitual) aspect of behavior (Baumeister et al. 1998). Bandura and Cervone (1983) found that the increase in effortful behavior following feedback on substandard performance is greater for individuals who are high in conation and self-efficacy than in their non-self-regulated counterparts. It follows from this finding that if instructional feedback is to contribute jointly to self-regulation and achievement, teachers should carefully plan for how they will use questioning and feedback which supports the self-efficacy of the student, i.e., scaffolds their learning so it is the student who believes that s/he is leading the discussion and solving the problem. If this is done regularly, the learner will generate internal feedback which makes them more engaged, effortful, and self-regulated. A self-regulatory concept of high relevance to formative assessment is volition. Volitional strategies are defined in Boekaerts and Corno’s (2005) model of SRL as “metacognitive knowledge to interpret strategy failure and knowledge of how to buckle down to work” (p. 206). Black and Wiliam (2009) explicitly connect volition to their theory of formative assessment because volitional self-regulation is essential if a learner is to remain persistent and overcome threats to self-esteem that may cause the student to divert resources away from their active participation in the learning process (‘growth track’) and expend resources on efforts to avoid interaction and withdraw from the situation (‘well-being track’). If students are to actively participate in their own learning progression it “is important to help students to acquire positive volitional strategies so that they are not pulled off the growth track onto the well-being track” (Black and Wiliam 2009, p. 14).

An issue common to both the internalization of external feedback and the generation of internal feedback resides in the ontology of the individual. The Vygotskian developmental level of ontology—the accumulated life experiences and cultural antecedents of a learner—may be analogized as a background ‘operating system’ in which the long-term memory (LTM) of the learner is located. The process of “formative interaction” provides new information to the operating system on the micro-genetic short-term memory level as teachers and students interact spontaneously, taking advantage of “moments of contingency” (Black and Wiliam 2009) to exchange ideas and information that enable learners to cross the zone of proximal development (ZPD) (cf. Vygotsky).

Heritage (2007) speaks on the validity of formative interactions to support learning, “the purpose of formative assessment is to promote further learning, its validity hinges on how effectively learning takes place in subsequent instruction” (Heritage 2007). This means that it is the extent to which formative interactions are successful in supporting the internalization and synthesis of new meanings that determine the “consequential validity” (Heritage 2007) of formative feedback strategies. Social and cultural antecedents determine the manner in which formative feedback influences the attainment of future learning goals. In particular, what goals are considered appropriate and how they can be achieved depends on the tacit knowledge of the human participants (Rogoff 2003). Butler and Winne (1995) emphasize the internal monitoring of a current state in a task as a continuous process, which operates as the trigger for SRL. After implementing strategies, learners monitor their progress toward goals, thereby generating internal feedback about the success of their efforts (Schunk 1998; Winne and Stockley 1998). Monitoring the outcomes of their effort provides grounds for reinterpreting elements of the task and their engagement with it, thereby directing subsequent effort and engagement with the learning process. Students may modify their engagement by setting new goals or adjusting extant ones; they may re-examine tactics and strategies and select more productive approaches or simply stop making the effort and give up (Butler and Winne 1995).

Formative Assessment: Assessment Is for Self-regulated Learning

Formative assessment encapsulates SRL (Part 1)

A theory of particular importance to SRL is Bandura’s (1986) Social Cognitive Theory which emphasizes meta-cognition and self-efficacy as fundamental to the development of SRL. The overarching target of formative assessment not only parallels SCT, but ‘encapsulates’ the fundamental goal of SCT as expressed by Bandura: “a fundamental goal of education is to equip students with the self-regulatory capabilities that enable them to educate themselves” (1997, p. 174). When SCT is taken together with studies by cultural and social context theorists arising from the work of L.S Vygotsky they combine to create the theory of formative assessment and comprehensively explicate how SRL strategies can be encouraged among students. Perhaps the most significant aspect of SCT is the proposition that individuals can consciously deploy self-regulatory strategies which mediate the internalization of external stimuli (Bandura 1986, 1997; Zimmerman 2002; Pintrich 1999, 2004; Black and Wiliam 2009). There is a strong reciprocal causality in play: individuals have some meta-cognitive and motivational qualities with which to regulate their environment while at the same time, the classroom (and home) environment either facilitates or frustrates the acquisition and use of self-regulatory characteristics (Bandura 1997; Zimmerman 2002).

Dimensions of self-regulated learning

Irving (2007) remarks that “students may benefit from formative assessment by developing self-regulated learning (SRL) behaviors in the classroom” (p. 13). In SRL, students undergo a recursive (but not necessarily linear) triptych: (1) planning phase—analyze tasks, set goals, and plan behaviors; (2) performance phase—monitor and control their behaviors, emotions, and motivation; and (3) evaluation phase—self-reflection based on feedback (Zimmerman 2000). The evidence obtained by both teachers and students from formative assessments is intended ultimately for student reflection who use it as ‘take-home’ information for self-management/control. Such data exposes the abstruse internal learning processes, making their thinking visible, and therefore invaluable to students as they participate in an enhanced learning process during which SRL strategies are internalized and put into practice (Schraw and Moshman 1995; Zimmerman 2000; Irving 2007). Bandura (1986, 1994, 1997) argues that self-regulated learning arises where strong perceptions of self-efficacy and transparent (formative) feedback co-exist. Bandura’s ideas concur with those of Schunk (1998) and Butler and Winne (1995) who see feedback as ‘pivotal’ to SRL, and Black and Wiliam’s (1998a, b, 2006, 2009) core notion of feedback as the material to be refined into the meta-cognitive processes required for self-regulation.

Despite the absence of a paradigmatic unity among SRL models, Pintrich (2000) establishes a consensus fundamental to an understanding about how formative assessments facilitate the acquisition of SRL strategies: (a) “learners as active constructive participants in the learning process” (p. 452); (b) “learners can potentially monitor, control, and regulate certain aspects of their own cognition, motivation, and behavior as well as some features of their environment” (p. 454); (c) “there is some type of criterion or standard (also called goals or reference value) against which comparisons are made in order to assess whether the process should continue as is or if some type of change is necessary,” (p. 452); and (d) self-regulatory activities mediate a three-way dynamic between personal and contextual characteristics and performance (p. 453). Karoly (1993) offers a further note on SRL as a process:

Self-regulation refers to those processes, internal and/or transactional, that enable an individual to guide his/her goal-directed activities over time and across changing circumstances (contexts). Regulation implied modulation of thought, affect, behavior, or attention via deliberate…use of specific mechanisms and supportive metaskills. (p. 23)

In summary, SRL is “an active, constructive process whereby learners set goals for their learning and then attempt to monitor, regulate, and control their cognition,” (Pintrich and Zusho 2002, p. 250). Self-regulated students are meta-cognitively, socially, motivationally, and behaviorally active in problem solving processes. Students who are advanced self-regulators typically deploy meta-cognitive strategies: (self)-verbalization (overt verbalization from self as self-instruction or from others who model the procedure), self-evaluation, and self-consequences (self-provided rewards or punishments) in order to successfully decode (comprehend and interpret) and encode new information which generates internal feedback.

Pintrich (1999) and his colleagues (Pintrich and Zusho 2002) elaborate, presenting four areas or dimensions of learning that can be regulated to support learning and realize performance goals. One area is cognitive and meta-cognitive requiring three learning strategies: (a) monitoring and controlling the use of rehearsal (recitation of information); (b) organizational (selecting, outlining, and organizing the main ideas); and (c) elaboration (explaining ideas to peers and others) strategies (Weinstein and Mayer 1986 as cited in Pintrich 1999). A second dimension that students can self-regulate is their participatory behavior. Students who are academically unprepared and unmotivated exhibit weak time-management strategies and may be tardy and unprepared to make an active and effortful contribution, even to the point of hostility towards authority. Motivational states are a third dimension that learners can self-regulate. There are many strategies that students deploy to support and sustain their own motivation. They include self-consequences, self-verbalization, and inventing new strategies which may transform task content; for example making learning activities into a game. These strategies put the process of learning under the student’s personal control and so improve the perceived importance or usefulness of material (Wolters 2003). The fourth and final dimension of learning that Pintrich (2004) identified as a potential target of students’ regulation is the Vygotskian, and therefore sociocultural notion of context or environment; including the aspects of task, classroom community, and cultural environment. Students might structure their environment to support learning by monitoring the noise, lighting, and temperature. In addition, this important dimension of SRL encompasses help-seeking and peer engagement strategies. When students know who to ask and act on this knowledge the social assistance they receive regulates students’ learning by actively engaging them with teachers, parents, peers, or ‘significant others’ (Vygotsky 1978; Zimmerman and Pons 1986; Pintrich 1999, 2004; Pressick-Kilborn and Walker 2002; Black and Wiliam 2006).

The gathering interest in social context is indicative of a relatively recent transformation in SRL research methodology. By 1997 Bandura himself had affirmed that “cognitive development, of course is situated in sociocultural practices”, declaring such proclamations to be “no longer newsworthy” (p. 227). The gradual change in perspective shifts the methodological angle view in a number of ways: (a) the move away from reductionist methodologies toward a more holistic analysis including contextual aspects such as interpersonal relationships and community norms; (b) away from a view of SRL as a linear process, to a focus on flexible patterns in varying activities over time, “the dynamic view of student activity and regulation is both theoretically interesting and practically useful for both teachers and for curriculum design” (Turner 2006, p. 295); and (c) greater emphasis on what people are doing and saying. Winne and Perry (2000) point to the fact that studies on self-regulation generate little knowledge about what individuals are thinking or doing. Therefore, “we need better mechanisms that provide a deeper understanding of how monitoring and regulation occurs within specific tasks” (Lajoie 2008, p. 471).

The theoretical elasticity of SRL has across time been extended to new lengths by the momentum away from reductionist perspectives and toward the holistic study of social context (i.e., collective efficacy); discourse; and perceptions of power and identity relevant to education in a twenty-first century ‘knowledge economy’. Such elements are, for social learning theorists at least, inherent to the theoretical frame of formative assessment. In fact, it will be seen in subsequent sections that the theory of formative assessment draws considerable energy from research which emphasizes mutual learning relationships, positive interdependence and a more open classroom which values the active and spontaneous (cf. Vygotsky and Polanyi) use of everyday tacit knowledge.

Differentiating formative assessment

Formative assessment is a quite different form of assessment which unlike other forms drives SRL strategy acquisition among learners. A number of relatively recent studies have related formative assessment to SRL directly (e.g., Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick 2006; Bose and Rengel; 2009; Black and Wiliam 2009). Linking formative assessment with the process of SRL further differentiates formative assessment from other forms of classroom assessment. Formative assessment is not a test or a tool (a more fine-grained test) but a process with the potential to support learning beyond school years by developing learning strategies which individuals may rely on across their entire life-span. Formative assessment is not a measurement instrument; it is not designed to provide a summary of attainment at pre-determined intervals. Instead it is designed to continuously support teaching and learning by emphasizing the meta-cognitive skills and learning contexts required for SRL; planning, monitoring and a critical yet non-judgmental reflection on learning, which both students and teachers use collaboratively to guide further learning and improve performance outcomes. The ‘big question’ then, is one of whether formative assessment attains “consequential validity”, that is, “validity [which] hinges on how effectively learning takes place in subsequent instruction” (Heritage 2007, p. 143). Key measures of validity are the level of autonomy, effort and engagement exhibited by students. Certainly a significant corpus of qualitative meta-studies exist which validate claims that formative assessment actualizes SRL, including Ruthven (1994) the OECD/CERI (2005, 2008), and the Assessment Reform Group (ARG 1999; Mansell et al. 2009).

Benchmark and interim assessments have been adopted by many school districts in the US to help monitor progress during the school year toward meeting state standards and NCLB performance goals. Typically these assessments are formal and provide teachers with information about the strengths and weaknesses of individual students against content standards. Wiliam (2004) calls such information “early warning summative”, and Shepard (2005b) remarks that the individual profile data from these assessments are not directly formative because (a) the data available are at too gross a level of generality and (b) feedback for improvement is not part of the process. Further, while there is debate about the value of immediate versus delayed feedback, there is consensus in the assessment community that learning benefits are more evident when “test results are available quickly enough to enable teachers to adjust how they’re teaching and students to alter how they’re trying to learn” (p. 86). Indeed, even the best that interim and benchmark assessments have to offer in this area is pedestrian when one considers the opportunities to gather evidence of student learning through “spontaneous” and “scaffolded” dialogue (cf. Vygotsky). Certainly the immediacy of continuous classroom feedback is a critical feature of formative assessment which delineates it from assessment tools designed to provide grades as summaries of achievement. The misunderstanding regarding the functions and goals of formative assessment is partly attributable to the marketing efforts of publishers and consultants, who contend that interim or benchmark assessments are formative (Popham 2006). Popham shares his personal experience of a dubious practice designed to sell tests to pressured and desperate educators, “more than one test company official has confided to me that companies affixed the ‘formative’ label to just about any tests in their inventory” (2006, p. 86). To package non-formative instruments (e.g., interim or benchmark assessments) as formative assessments even raises a legal contention because to label non-formative assessment as formative is to render such assessments “unfit for the purposes for which goods of the same description would ordinarily be used” (United Nations, 1980, Part III, Chapter II, Article 35). The ARG (Mansell et al. 2009) in their paper entitled ‘Assessment in School: Fit for Purpose?’, reported on the confusion among assessment experts from Canada, the US, UK, continental Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, who met at a conference to discuss the issues facing teachers as they worked to establish assessment and learning relationships which create legitimate partnerships with their students. There was a consensus among the delegates that the term ‘formative assessment’ lacked clarity, and that the confusion is “exacerbated by some policy-makers appropriating and using it in ways that contradict its true intentions” (Mansell et al. 2009, p. 23). The delegates focused on the problem of determining how to close the gap between current status and desired outcome, noting that many policy-makers believe that the sine qua non is not sharing standards and criteria as the OECD, ARG, and others assert but is in fact frequent summative testing. The premeditated subversion of the assessment process, however well intentioned or well planned is perhaps the paramount concern among those researchers who advocate for formative assessment. Heritage (2010) cautions that:

…we already risk losing the promise that formative assessment holds for teaching and learning. The core problem lies in the false, but nonetheless widespread, assumption that formative assessment is a particular kind of measurement instrument, rather than a process that is fundamental and indigenous to the practice of teaching and learning. This distinction is critical, not only for understanding how formative assessment functions, but also for realizing its promise for our students and our society. (p. 1)

In their discussion of the practical value of formative assessment, Dunn and Mulvenon (2009) include the metaphor of a “hammer” to represent ‘the assessment tool’. The purpose of such a tool can be understood without any ambiguity by assigning an agreed upon definition which makes clear the intended use for that particular tool without any need to discuss its purpose:

It is easier to simply ask for and receive a hammer than to provide a description of the intended use (i.e., if you ask for an item that can make a hole in the wall, you might receive a sledge hammer in lieu of a hammer). (p. 3)

For Dunn and Mulvenon therefore, one must place quotation marks around ‘formative assessment’ until it has been assigned a definitive label which expresses its intended purpose with rigid precision. Such perspectives are understandable in political climates of scientific rationalism, where certain sections of the research community may quite correctly regard formative assessment as “ethereal” (Dunn and Mulvenon 2009) and “fuzzy” (Dorn 2010). A good example is provided by the research taking place at the Educational Testing Service (ETS) in the US, where some project scientists would like to reduce formative assessment to a single agreed upon definition which explains how it designs order into the parts of the ‘instructional system’ (Bennett 2011). Such scientific definition makes it possible to measure and predict the exact behavior of any physical system across the long time horizons required by policy-makers. Consequently, attempts continue to define formative assessment as a cognitive ‘tool’ (Bennett 2011). The inquiry into how formative assessment designs order into the parts requires the mapping of the ‘cognitive architecture’ associated with formative assessment by disassembling the process into a specific number of component parts. These parts are then categorized, coded and reassembled, allowing the research scientist to identify and then manipulate specific aspects of the process and which permits the measurement of the effect each manipulation has on learning outcomes. Policies that support the use of methodological reductionism also lead to the packaging of formative assessment (often literally as test booklets) as a skillfully made artifact to be used as prescribed, e.g., to be taken twice daily after recess and lunch. While this may be an improvement upon the assessment practices found in many classrooms it is still not directly formative.

Political considerations aside, methodological reductionism does not adequately address the study of complex, non-linear, nested, and multi-dimensional social systems. In general terms, human behavior cannot be assumed to be predictable or repeatable. In specific terms, assessment takes place in an “indeterminate zone of practice”, which requires teachers and students to regulate learning by “thinking on their feet” (Schön 1987). Consequently, not only do the outcomes of reductionist methodologies fail to deal with complex social realities, they also lack external validity and may not be generalized across populations. The work of the social constructionist is more complicated than that of a paleontologist, who can take a bone or two of a dinosaur and reconstruct the whole animal. When non-linear systems interact with the environment emergent properties cannot be predicted, because non-linearity leads to instability and uncertainty, hence the need for a theoretical framework which includes methodologies which explicitly investigate the grain of non-linear systems, e.g., discourse analysis, (Mercer 1995, 2004; Black and Wiliam 2009; Rex and Schiller 2009). Some in the scientific community have recognized the problem of reductionist methodologies and have started to question its credibility, “during the past few decades, more and more scientists have concluded that this and many other of science’s traditional assumptions about the way nature operates are fundamentally wrong” (Freedman 1992, p. 30). Freedman (1992) suggests that reductionism remains rooted in nineteenth century scientific methodology, which posited a neat correspondence between cause (experimental manipulation) and effect (learning outcome), for example Newton’s laws of motion. It should of course be carefully noted that there are many other aspects of assessment research taking place at the ETS which hold agreement with Freedman and rebuff the nineteenth century notion that order is designed into the parts of a system (Wylie, 2011, personal communication). Studies which assume a holistic approach focus on how order emerges from the interaction between those parts as a whole. Twenty-seven years ago, White (1984) observed:

To proceed holistically is to see things as units, as complete, as wholes, and to do so is to oppose the dominant tendency of our time…Analytic reductionism assumes that knowledge of the parts will lead to an understanding of the whole, a theory which works very well with machinery or other objects, but less well with art forms or life forms. (p. 400)

Sampson (2004) refers to the potential of discourse to “reshape” reductionist policies. Accordingly, in more recent years various empirical studies have revealed the profound impact of carefully structured opportunities for participation and discourse in communities, finding that it is crucial to activate holistic social relationships and achieve community consensus to realize and sustain achievement (Bandura 1993; Sampson et al. 1997; Sampson 2004; Black and Wiliam 2006; Putney and Broughton 2011). Both analytical reductionists and social holisticists exhibit considerable interest in formative assessment, the goals of which explicitly seek to support individual learning outcomes by encouraging SRL strategies among students. When their work is synthesized into a functional framework (as the theory of formative assessment is designed to do) it operates to triangulate the understandings of the research community in different and newly valid ways.

An issue of global relevance

There is a very significant corpus of international research interest in formative assessment and the development of autonomous lifelong learning competences. Germany provides a good example of a nation with a long tradition of philosophers and educational reformers who proposed alternatives to teacher-centered instruction (Reformpädagogik) as a more appropriate approach to teaching that meets students’ needs for competence, autonomy, and self-determination. German studies have emphasized the role of feedback and that teachers should become more aware of how they provide feedback to students; specifically, the kinds of interactions which determine the internalization of environmental stimulus (the “formative interaction”) which may either promote or diminish autonomy (Köller 2005). The work of innovators; Montessori, Freinet, Kerschensteiner, and Steiner have been very influential in advancing the proposition that formative practices are more effective as cues for SRL than teacher-fronted methods of instruction. For example, Herrmann and Höfer (1999) introduced the use of diaries (Lerntagebücher) into the daily routine of a German secondary school. As students became more skilled in the use of this new ‘technology’ they were found to “provide opportunities for students to reflect on their own learning processes and to detect and correct deficits over time. Diaries thus serve as a tool for autonomous and self-regulated learning” (Köller 2005, p. 268).

In the global context formative assessment, autonomy, lifelong learning, and SRL are of paramount importance (OECD/CERI 2005, 2008; Black and Wiliam 2005). Research consistently finds that when students are effectively formatively assessed, they participate actively in their own learning progression by consciously monitoring and regulating product-oriented learning processes (Black and Wiliam 1998a, b, 2006, 2009; Zimmerman and Pons 1986; Assessment Action Group/AiFL Programme Management Group [AAG/APMG], 2002–2008; Wolters 2003; Pintrich 1999, 2004). The OECD’s (2005) Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) based in Paris, France conducted extensive international case studies across eight nations which had incorporated formative assessments into their national policy frameworks (Canada, Denmark, England, Finland, Italy, New Zealand, Queensland in Australia, and Scotland). The OECD/CERI case study approach provides a broad spectrum of classroom-level data derived from observations, interviews and artifact analysis which illuminates current understandings of how practitioners may use formative assessment to support learning in practical contexts. Ruthven (1994) reviewed 50 papers presented at the invitational 2nd International Congress on Mathematical Instruction (ICMI) seminar collected across two volumes called: Investigations into Assessment in Mathematics Education (Niss, 1993a) and Cases of Assessment in Mathematics Education (Niss, 1993b). Presentations from European, North American, Caribbean, Asian, Oceanian, and Middle Eastern scholars consistently indicated that a most productive trend in mathematics research entails, “increasing the integration of processes of teaching, learning and assessment” (Ruthven 1994, p. 433). After reviewing the content of the papers thematically, Ruthven discovered a number of recurrent themes regarding the positives of formative practice, which operate to delineate it from traditional forms of assessment:

[i] performance on external tests was improved by the close involvement of students in the assessment process through self- and peer-assessment…[ii] given the complexity of the teacher’s task, it may be more realistic, and ultimately more productive, to enhance the student role in the formative assessment process…[iii] The implications of acknowledging students’ personal knowledge from a constructivist orientation, and their personal goals from the perspective of critical education, call for the promotion of the student from the status of object of assessment to that of subject shaping the process of assessment …[iv] Learners must be given the means of changing their sense of control and responsibility for their learning, and their attributions of success and failure…[v] Other effects were, improved student capacity to evaluate their work, and reduction of anxiety about assessment. (p. 448)

French research studies consistently emphasize interactive formative assessment, between teacher and students and among students, affirming that the theory of formative assessment “constitutes a framework of social mediation that fosters the student’s increasing capacity to carry out more autonomous self-assessment and self-regulated learning” (Allal and Lopez 2005, p. 241; Doyon and Juneau 1991; Doyon 1992). The international consensus on the findings support the contention that formative assessment practices place certain demands on students, requiring them to become self-regulated learners.

Connecting Objectives, Goals, and Strategies

Before discussing the relational dynamic between the goals of formative assessment and the acquisition of SRL strategies; that is, how formative assessment encapsulates and ‘drives’ SRL and how SRL environments are inherently formative, it is necessary to bring focus to what some studies (e.g., Dunn and Mulvenon 2009; Dorn 2010; Young and Kim 2010; Bennett 2011) have criticized as a shapeless theoretical gestalt. In their seminal work, Black and Wiliam (1998b) provide an explanation of formative assessment as “all those activities undertaken by teachers, and by their students in assessing themselves, which provide information to be used as feedback to modify the teaching and learning activities in which they are engaged” (p. 2). Black and Wiliam place the emphasis on modification of teaching and learning strategies and the inclusion of students as ‘agents’ in shaping their own learning experience. The description of formative assessment is completed by a procedural element, identical to the Vygotskian notion of scaffolding—that classroom assessment becomes formative only when it is used as evidence, which teachers and students use to adapt instructional content in a way which addresses emergent misconceptions, scaffolds partial understandings and so on.

SRL: taxonomy of strategies and characteristics

The strategies and characteristics which appear in Table 1 are those that self-regulated students use to bring self-influence to bear on their learning experiences. They are drawn from the work of Bandura (1986, 1997), Zimmerman and Pons (1986), and Pintrich (1999, 2004).

An important aspect to this article is the claim that formative assessment encapsulates SRL and further, that there exists a bi-directional dynamic between the goals of formative assessment, (which foster SRL strategies among students) and the strategies deployed by self-regulated students, (whose learning strategies are pursuant of formative assessment goals). In the opening section, ‘Introduction to the Learning Community’ the theory of formative assessment was given early shape by two objectives: assessment for learning and assessment as learning. The forthcoming section (‘formative assessment encapsulates SRL [Part 2]’) decomposes the objectives into individual goals as derived from a number of coordinated sources (ARG 1999; Black and Wiliam 1998b; Sadler 1989; OECD 2005; Cauley and McMillan 2010) and connects them to the SRL strategies presented in Table 1

Formative assessment encapsulates SRL (Part 2)

AfL (see Fig. 1) directs classroom practitioners to work together with students in four goal areas: Goal 1: Communicate to students the goals of the lesson and the criteria for success. As noted earlier, while differing models of SRL exist, however Pintrich establishes a consensual foundation of SRL as a process in which learners set goals for their learning and then attempt to monitor, regulate, and reflect on their cognition (Pintrich 1999; Pintrich and Zusho 2002); Goal 2: Engage students in discussions about study habits and strategies which sustain improvement. Students move toward greater self-regulation by developing effective work and study habits, such as time management, seeking help, and engaging peers (Zimmerman and Pons 1986; Pintrich and Zusho 2002), using feedback (Schunk 1998; Bandura 1997), and planning, monitoring, and evaluating schoolwork (Butler and Winne 1995; Bose and Rengel 2009); Goal 3: Involve students in previewing and planning forthcoming work. Planning, particularly global planning, is thought to be an important sub-process of meta-cognition and one used by experts (Schraw and Moshman 1995); Goal 4: Inform students of who can give them help if they need it and permit full access to such help. Help-seeking, peer engagement, and the inclination to access non-classroom resources are characteristics inherent to SRL (Zimmerman and Pons 1986). AaL (see Fig. 1) focuses on the social context and on self and peer assessment activities: Goal 5: Provide opportunities for students to become meta-cognitive and build knowledge of themselves as learners by encouraging students to evaluate and reflect on the quality or progress of their work. Bruce (2001) suggests that students gain the most benefit from individual activities when they are encouraged to check their work before turning it in. Checking work for errors is the self-evaluation of cognitive quality and progress and considered in many SRL studies as the basic construct for planning, monitoring, and reflecting upon cognition (e.g., Zimmerman and Pons 1986; Pintrich 1999; Bandura 1997); Goal 6: Create a non-comparative, productive environment free of risks to self-esteem founded upon cooperation and dialogue. Bandura (1997) and Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006) caution that negative psychological states may lower efficacy beliefs which in turn impact students’ self-regulatory dispositions and lead to poor performance; Goal 7: Support students as they take more responsibility for their learning. For Zimmerman and his colleagues, self-regulation enables students to develop a set of constructive behaviors that can positively affect learning (Zimmerman and Pons 1986; Zimmerman 1989; Zimmerman 2000; Zimmerman and Pons 1986; Schunk and Zimmerman 1997). Aspects of self-responsibility include a collaborative approach to: adapting or inventing learning strategies; keeping records, and monitoring; rehearsing and memorizing; time management; and goal setting and planning. These strategies are required if students are going to become responsible for decisions about their own learning and performance; in perhaps the clearest statement of constructivist principle Goal 8 directs teachers and students to: Provide opportunities for frequent participation in the process of learning with their teacher as their advisor and with their peers in a climate of equality and mutuality. Effective SRL focuses on helping students become independent and autonomous thinkers; “through critically examining others reasoning and participating in the resolution of disagreements, students learn to monitor their thinking in the service of reasoning about important [mathematical] concepts” (Artzt and Yaloz-Femia 1999 as cited in, Pape et al. 2003, p. 181). Importantly, research also shows that any student, even those ‘at risk’, can learn to become more self-regulating (Pintrich and Zusho 2002; Black and Wiliam 2006).

Across the last 10–15 years many nations have explicitly recognized the potential of formative assessment practices to actualize the SRL strategies described above (OECD 2005, 2008). For example, The Finnish National Board of Education has formulated the guiding principles for student assessment in public comprehensive schools. Most relevant to an inquiry into SRL is that: (a) assessment should be individual and versatile; (b) feedback should act to support self-knowledge and motivation; (c) lifelong learning competencies should be encouraged among student by showing them how to set realistic learning goals; and (d) assessment is considered to be a process that exists to support learning and develop students’ self-assessment skills. Voogt and Kasurien (2005) reiterate the way in which national philosophy determines educational policy, “the focus on self-evaluation also reflects a more general philosophy in the Finnish educational system that it is more important to focus on development than comparison” (p. 150).

Internalization, Environment, Interaction, and Experience

By drawing from socio-cognitive and sociocultural theories, a theory of formative assessment was forged which took account of these four essential ‘factors of knowledge production’. The theory of formative assessment unifies a diverse corpus of research on: (a) the internalization of new environmental stimulus; (b) the interaction between the internal and the external; and (c) the prior knowledge of the learner.

An area of pivotal importance to effective SRL strategy acquisition and “at the heart of both socio-constructivist perspectives and cognitive psychologist perspectives on learning, is the significance of prior knowledge” (Myhill and Brackley 2004, p. 264). Students are constantly internalizing new information and bringing their own everyday, spontaneous (cf. Vygotsky) and tacit (cf. Polanyi) conceptions and misconceptions into the classroom. The concept of schematic knowledge, first proposed by Bartlett (1932), “provides the overall perspective which enables us to integrate what we hear with what we already know, and to fit individual bits of information into a coherent argument” (Cook-Gumperz 1986, p. 66). Thus, the learner produces meaning and understanding through an internal process of interchange between new knowledge and previous knowledge during which new meanings are continuously evolving out of prior understanding. The amended schemata of meanings are stored in the LTM, to be retrieved, expanded, and modified in the light of new and changing experiences or understandings: “knowledge is constructed by the individual knower, through an interaction between what is already known and new experience” (Edwards and Westgate 1994, p. 6). This expresses the internal aspect of Black and Wiliam’s (2009) notion of “a formative interaction” as an “interaction between external stimulus and feedback, and internal production by the individual learner” (p. 11). This, state Black and Wiliam (2009) involves looking at the three aspects, the external, the internal, and their interactions. The remaining two parts of Black and Wiliam’s (2009, p. 11) conception of a formative interaction: the external and the interaction between the internal and external raise the question: Do practitioners really understand how experience facilitates (or frustrates) the creation of new schematic knowledge from a sociocultural perspective? Anderson et al. (2007) assert that, “situative and other sociocultural perspectives on learning construe knowing as fundamentally social (Gutiérrez and Rogoff 2003; Lave and Wenger 1991) and view participation in discourse, for example, “as the primary characterization of learning and knowing” (pp.1724–5). For socioculturalists the creation of meaning is embedded within the interaction component. Meaning is socially constructed because “human thought is consummately social: social in its origins, social in its functions, social in its form, social in its applications” (Geertz cited in Bruffee 1993, p. 114). In this epistemology learning is inevitably embedded in language, itself embedded in human discourse; experience precedes pattern and pattern precedes meaning; “whether we are talking about unicorns, quarks, infinity, or apples, our cognitive life depends on experience” (Eisner and Peshkin 1990, p. 31). For Rogoff (2003) and Mercer (1995), knowledge is a process of guided construction (cf. Dewey) and so new meanings are acquired as part of “a developmental process in which earlier experiences provide the foundations for making sense of later ones” (p. 33). Put simply, the theory of formative assessment holds that learning and development occur more successfully when individuals interact indirectly (through observation) and directly through active participation with the conscious intention of regulating their own learning progression.

When discussing learning and development it is important to understand that they are not synonymous. A point well made by Black and Wiliam (2009), “Vygotsky drew a clear distinction between learning and development. The latter [development] requires changes in the psychological functions available to the learner, while learning involves the acquisition of new mental capabilities, without changes in the available psychological functions” (p. 19). Delineating ‘learning’ and ‘development’ as separate terms with distinct meanings impacts upon the description of probably the best known fundament of socioculturalism, Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development:

The zone of proximal development (ZPD) is not, therefore, just a way of describing what a student can do with support, which might be simply learning, it is a description of the maturing psychological functions rather than those that already exist. A focus in instruction on the maturing psychological functions is most likely to produce a transition to the next developmental level and “good learning” is that which supports the acquisition of new psychological functions. This careful distinction between learning and development is a central feature of Vygotsky’s work that is often overlooked. (Black and Wiliam 2009, p. 19).

For both learning and development the prior knowledge of the participants either retrieved during self-reflection or elicited by teachers or peers provides the starting point for the pursuit of formative assessment goals which advance SRL strategies among students. Yin et al. (2008) draw from David Ausubel’s (1968) robust ‘subsumption theory’ which strongly emphasizes the value of existing knowledge when they more moderately contend that “the presence and persistence of alternative conceptions, the restructuring or reorganization of existing knowledge, or conceptual change, has become a very important component of teaching and learning” (p. 338). Clearly then, the starting point for conceptual change is to discover what the learner already believes to be true.

In addition to locating learning and development within the ZPD, Vygotsky (1987) rejected reductionism and expressed the inseparable unity between the individual and social and cultural context when he observed that in order to understand how water extinguishes a flame one does not attempt to reduce it to its elements. The scientist will “discover, to his chagrin that hydrogen burns and oxygen sustains combustion. He will never succeed in explaining the characteristics of the whole by analyzing the characteristics of the elements” (Vygotsky 1987, p. 45). An analogy also used by Wolfson (1977) to illustrate the inseparability of thinking and feeling. In combining similar theories with differently weighted emphases, formative assessment attains theoretical synergy by acknowledging that the regulation of cognitive development is determined by reasonably stable internal values and beliefs (Butler and Winne 1995; Efklides 2011), which are challenged or reinforced by external feedback arising from active engagement with a collective or community (Vygotsky 1978; Bandura 1997). A central and distinguishing thesis in this approach is that the structure and development of human psychological processes, which support the development of SRL emerge through participation in culturally mediated, historically developing, interpersonal activity involving cultural practices and tools (Cole 1996). As such, “self and other is not a duality, because they go so together that separation is quite impossible” (Kelley 1962 p. 9). Luria (1979) makes a consonant observation:

The origins of higher forms of conscious behavior were to be found in the individual’s social relationships with the external world. But man is not only a product of his environment; he is also an active agent in creating that environment. (p. 43)

Lajoie (2008) remarks that, “it is the interaction between the mind and environment that presents the most interesting questions in terms of the active nature of learning” (p. 471). The reciprocal interaction between the environment, which stimulates individuals’ regulatory responses and the minds of individuals’, which trigger subsequent judgments or evaluations is captured by Bandura (1977, 1986) concept of ‘reciprocal determinism’. For Bandura, when people reflect upon the outcomes of their behavior (verbal and social interactions) they may consciously adapt internal personal factors (cognitive abilities, tacit opinions, attitudes, and beliefs) which cause changes in the environment. Bandura (1986) called this agentic three-way interaction a ‘triadic reciprocality’—a notion comparable to Black and Wiliam’s (2009) aforementioned conception of “a formative interaction” (p. 11). The process of active agency is well expressed by Kirsh and Maglio (1995), who use the term “epistemic actions”, i.e., conscious self-regulatory actions, such as social interaction (e.g., discourse) and environmental structuring (e.g., adjusting noise or temperature), allowing individuals to access the information they need to more effectively achieve learning outcomes.

Processing assessment information