Abstract

Coronary artery spasm has been considered one of the major mechanisms causing dynamic stenosis of epicardial coronary arteries, which can evoke acute myocardial ischemia. Vasospastic angina caused by coronary artery spasm has a wide clinical spectrum: one of its typical clinical manifestations is variant angina. Coronary vasospasm has also been documented to contribute to the development of unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction [1]. Classically, coronary artery spasm is diagnosed by an invasive provocative procedure during diagnostic coronary angiography. Since various noninvasive diagnostic tests for fixed atherosclerotic stenosis of epicardial coronary arteries (exercise ECG, stress echocardiography, and nuclear tests) are being used in routine daily practice, it would be useful to establish a reliable, noninvasive, and safe diagnostic method to document coronary artery spasm in the management of patients with vasospastic angina.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Regional Wall Motion Abnormality

- Epicardial Coronary Artery

- Coronary Spasm

- Coronary Artery Spasm

- Coronary Vasospasm

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Coronary artery spasm has been considered one of the major mechanisms causing dynamic stenosis of epicardial coronary arteries, which can evoke acute myocardial ischemia. Vasospastic angina caused by coronary artery spasm has a wide clinical spectrum: one of its typical clinical manifestations is variant angina. Coronary vasospasm has also been documented to contribute to the development of unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction [1]. Classically, coronary artery spasm is diagnosed by an invasive provocative procedure during diagnostic coronary angiography. Since various noninvasive diagnostic tests for fixed atherosclerotic stenosis of epicardial coronary arteries (exercise ECG, stress echocardiography, and nuclear tests) are being used in routine daily practice, it would be useful to establish a reliable, noninvasive, and safe diagnostic method to document coronary artery spasm in the management of patients with vasospastic angina.

The rare episodic nature of coronary artery spasm makes it extremely difficult to document spontaneous coronary vasospasm in clinical practice. The noninvasive stress tests currently used are ergonovine [2], acetylcholine [3], and systemic alkalosis by hyperventilation [4]. Of these, spasm-provocation testing using ergonovine is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of coronary artery spasm because of its high sensitivity and specificity. Acetylcholine seems to have comparable diagnostic validity for intracoronary administration, but its short half-life for the abundant pseudocholinesterase in human plasma makes intravenous injection inadequate for spasm provocation.

1 Basic Considerations

Ergonovine maleate is an important oxytocin alkaloid and a member of the ergobasine group, an amine alcohol derivative of lysergic acid. This drug can induce coronary vasoconstriction in patients who have undergone heart transplantation, which suggests that it does not act via the central nervous system. This drug is believed to stimulate α-adrenergic and 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptors [5]. After intravenous injection, the half-life of the distribution phase is between 1.8 and 3 min, and the half-life of the disappearance phase is between 32 and 116 min [6]. This rapid mode of action explains why coronary spasm most often occurs between 2 and 4 min after the injection. The use of ergonovine in incremental doses starting with an intravenous injection of 0.05–0.1 mg followed by small increments of 0.1–0.15 mg at 5-min intervals up to a maximum cumulative dosage of 0.35 or 0.4 mg is generally recommended [1]. This general guideline is based on the finding that the cumulative doses (0.1 + 0.2 + 0.3 + 0.4 mg) at 5-min intervals have the same effects as a single dose of 0.4 mg [1]. The provocative test with ergonovine performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory has a high sensitivity (98 %) and specificity (98.7 %) [7].

2 Protocol

For a diagnosis of vasospastic angina, the possibility of significant fixed atherosclerotic stenosis of major epicardial coronary arteries is usually ruled out by means of the exercise stress test and/or pharmacological stress echocardiography. All cardioactive drugs (β-receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, and nitrates) should be discontinued for at least five half-lives; however, nitroglycerin should be administered sublingually as necessary. Resting hypertension is usually controlled using angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; uncontrolled hypertension is a contraindication of this test.

It should be remembered that some drugs, especially long-acting calcium channel blockers, may have persistent effects on coronary vasomotor tone as long as 2–3 weeks after discontinuation [8, 9].

Figure 16.1 shows the classic protocol of ergonovine echocardiography. A bolus injection of ergonovine (50 μg) is administered intravenously at 5-min intervals until a positive response is obtained or a total dose of 0.35 mg is reached. The 12-lead ECG is recorded after each ergonovine injection and left ventricular wall motion is monitored continuously. Positive criteria for the test include the appearance of transient ST-segment elevation or depression greater than 0.1 mV at 0.08 s after the J point (ECG criteria) or reversible wall motion abnormality by two-dimensional echocardiography (ECG criteria). The criteria for terminating the test are as follows: positive response defined as ECG or echocardiographic criteria, total cumulative dose of 0.35-mg ergonovine, or development of significant arrhythmia or changes in vital signs (systolic blood pressure >200 mmHg or <90 mmHg). An intravenous bolus injection of nitroglycerin is administered as soon as an abnormal response is detected; sublingual nifedipine (10 mg) is also recommended to counter the possible delayed effects of ergonovine. These drugs can be administered as needed. The protocol can be modified just to decrease the test time (Fig. 16.1), with bolus doses of 50, 100, 100, and 100 μg every 5 min up to a cumulative dose of 350 μg.

3 Noninvasive Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Spasm: Clinical Data

Bedside ergonovine echocardiography has been reported to be accurate and safe [8–18] (Figs. 16.2 and 16.3). The sensitivity of echocardiographic criteria (detection of reversible regional wall motion abnormalities) is higher than 90 %, which is far greater than that of ECG criteria (ST-segment displacement, 40–50 %). Characteristic ST-segment elevation during ergonovine testing occurred in about one third of patients with variant angina [16]; the lower sensitivity with ECG criteria can be partially explained by an earlier development of regional wall asynergy during myocardial ischemia in the so-called pre-electrocardiographic phase rather than a true false-negative finding [10–13]. The earlier detection of ischemia with higher sensitivity is very important from the safety point of view, as the vicious cycle of the ischemic cascade can be terminated earlier and the risk associated with prolonged ischemia reduced. According to a single-center report of ergonovine echocardiography performed on 1,372 patients [16], the test showed very high feasibility (99.1 %); transient arrhythmias – including sinus bradycardia (n = 10), ventricular premature beats (n = 10), short-run ventricular tachycardia (n = 2), and atrioventricular block (n = 4) – developed in 1.9 % (26/1,372) of the patients studied. All of these arrhythmias were transient and promptly reversed with the administration of nitroglycerin and nifedipine, as described earlier. Although intracoronary nitroglycerin could not be used to reverse coronary vasospasm in this protocol, there were no serious complications such as development of myocardial infarction or fatal arrhythmia during the test [8, 9].

Representative examples of (a–d) ergonovine stress echocardiography and (e, f) coronary angiography in a 53-year-old man with early-morning chest pain. Treadmill test results were negative up to stage 4 of the Bruce protocol, and ergonovine echocardiography was done. Left ventricular wall motion at end-systole recorded in the parasternal short-axis view was demonstrated in quad-screen format. (a) Basal status. (b) Left ventricular wall motion after injection of 0.05-mg ergonovine. (c) Regional loss of systolic myocardial thickening in the mid-inferior segment with an ergonovine dose of 0.1 mg and (d) recovery of regional wall motion abnormality with nitroglycerin, a finding suggestive of myocardial ischemia in the region of the right coronary artery due to coronary vasospasm. (e) Coronary angiogram taken 2 days later revealed a normal right coronary artery. (f) Intracoronary injection of acetylcholine (ACH) provoked total occlusion of the proximal right coronary artery, which was compatible with coronary vasospasm (From Song et al. [9], with permission)

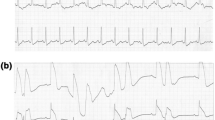

Representative example of ergonovine echocardiography (a, b) and invasive spasm-provocation testing during diagnostic coronary angiography (c, d) in a 47-year-old man. Left ventricular wall motion at end-systole recorded in the apical two-chamber view was demonstrated (a, b). Compared with the basal status (a), prominent loss of systolic thickening in the inferior wall developed with an ergonovine dose of 0.15 mg (b, white arrow), which was compatible with myocardial ischemia due to coronary artery spasm in the right coronary artery territory. Coronary angiogram taken 3 days later revealed no significant fixed disease. Intravenous injection of ergonovine (E1) provoked total occlusion of the distal right coronary artery (C), and the angiogram after injection of nitroglycerin (N) showed completely normal right coronary artery and relief of total occlusion (d) (Adapted from Song et al. [16], with permission)

Unlike other stress tests for fixed atherosclerotic stenosis of coronary artery, this test shows high sensitivity even in patients with single-vessel spasm [16]; the transmural nature of supply ischemia due to coronary artery spasm may explain this difference.

As this test also showed very high specificity (>90 %) for the diagnosis of coronary artery spasm before coronary angiography, invasive coronary angiography and spasm-provocation testing can be avoided for the diagnosis of vasospastic angina [16, 18].

4 Special Safety Considerations

Issues regarding the safety of spasm-provocation testing are summarized in Table 16.1.

Ergonovine echocardiography testing, undertaken either in the catheterization laboratory or at the bedside, is a risky and challenging procedure, demanding a high degree of skill on the part of the operator [8]. Angiographic demonstration of reversible total occlusion of one of the major epicardial coronary arteries is in itself enough for a diagnosis of coronary vasospasm. If, however, angiography reveals only moderate vasoconstriction, as occurs more frequently in the daily clinical practice of provocation testing, other indexes of myocardial ischemia are necessary before a definite diagnosis of coronary vasospasm can be made. In the catheterization laboratory, the development of chest pain and electrocardiographic changes, well known as relatively late events in ischemic cascade, are classic markers of myocardial ischemia. The usual 3- to 4-min wait after each injection of the drug before repeat angiography without sensitive monitoring of ischemic cascade in the catheterization laboratory may also contribute to the potential danger of the procedure. This is because the development of serious arrhythmia or myocardial infarction depends on the duration of the preceding myocardial ischemia during spasm provocation.

In addition to concerns about disturbing vasomotor tone with the catheter, injecting a contrast agent into the coronary circulation during a severe ischemic episode may increase the risk of the procedure. Myocardial imaging rather than angiography has been proposed as a more sensitive, more specific, and safer method of identifying coronary vasospasm by some physicians. The importance of intracoronary nitroglycerin for reversing an intractable vasospasm that is not responsive to sublingual and intravenous nitroglycerin has been reported [19, 20], but other published investigations indicate that intracoronary nitroglycerin is not a prerequisite for spasm-provocation testing [8–18].

The most important advantage of ergonovine echocardiography is its capacity for detecting regional wall motion abnormalities, which are sensitive and specific markers of myocardial ischemia, even before the appearance of chest pain or electrocardiographic changes. During ergonovine echocardiography, the wall of the left ventricle can be continuously monitored, with early termination of myocardial ischemia based on the detection of regional wall motion abnormality; this is a potential and theoretical advantage of the test. In our study [8, 16], less than half of the patients with definite wall motion abnormalities showed ECG changes suggestive of myocardial ischemia, which is compatible with the premise described above. Further multicenter investigation is needed to determine whether early detection and termination of myocardial ischemia based on regional wall motion abnormalities can completely obviate the need for temporary pacemaker backup. Continuous monitoring of the ventricular wall motion without interruption during ergonovine echocardiography can contribute to the detection of multivessel coronary spasm involving the right and left coronary arteries. This is almost impossible during invasive spasm-provocation testing in the catheterization laboratory, as termination of spasm in one coronary artery territory is necessary. Simultaneous catheterization of both coronary ostia for demonstration of potential multivessel spasm is not a routine procedure due to low clinical feasibility.

5 Potential Clinical Impact

Noninvasive ergonovine stress echocardiography is an effective and reasonably safe way of diagnosing coronary vasospasm in routine clinical practice for patients visiting the outpatient clinic [16] or for those admitted to the coronary care unit under the clinical impression of unstable angina pectoris [15]. Although clinical usage of spasm-provocation testing has decreased significantly in Western countries and spasm-provocation testing is no longer a routine diagnostic procedure, one outcome study [21] reveals significantly higher mortality and event rates with a positive result of ergonovine stress echocardiography (Fig. 16.4) in patients with near-normal coronary angiogram or in those with negative stress test results for significant fixed stenosis. These results demonstrate the powerful prognostic implication of noninvasive ergonovine stress echocardiography in routine daily practice for differential diagnosis of chest pain syndrome. As this test provides an effective and powerful means of risk stratification on the basis of the presence of provocable ischemia in patients with no evidence of significant fixed coronary stenosis, either by direct invasive or noninvasive (by 64-slice computed tomography) coronary angiography or by noninvasive stress testing, consideration of ergonovine stress echocardiography for complete differential diagnosis of mechanisms of myocardial ischemia should be encouraged in various clinical scenarios involving patients with chest pain syndrome [22], such as patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries and a history of angina at rest, aborted sudden death [23], flash pulmonary edema [24], or suspected left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome [25]. The usefulness of the ergonovine test in monitoring the efficacy of antianginal therapy has been documented [26], but its clinical value remains uncertain. It is probably inappropriate to use the test in patients in whom the diagnosis is already established by clinical history or with concomitant ischemia in the presence of angiographically documented coronary artery disease. The test can be less safe in patients with uncontrolled hypertension and previous stroke [27]. It is also important to consider vasospasm – and, if appropriate, vasospasm testing – in several clinical settings remote from the cardiology ward when ergometrine-containing or serotonin-agonist drugs are routinely given and may occasionally precipitate “out-of-the-blue” cardiological catastrophes mediated by coronary vasospasm: ergometrine given in the obstetric clinic to reduce uterine blood loss in the puerperium phase [28–33] or bromocriptine given for milk suppression [34, 35], sumatriptan or ergometrine used in neurology for migraine headaches [36–39], 5-fluorouracil and capecitabine (an oral 5-fluorouracil prodrug) given as chemotherapy in (breast and colon-rectal) cancer [40–44], and, with increasing frequency, cocaine as a cause of chest pain in the ER [44, 45]. In all these conditions, it is essential to think of vasospasm so as to recognize it.

Survival (a) and event-free survival rates (b) according to the results of ergonovine echocardiography (Erg Echo) in patients with near-normal coronary angiogram or negative stress test results for significant fixed stenosis. (−), negative test; (+), positive test (Adapted from Song et al. [21])

6 Pitfalls

In spite of the contrary evidence in the literature [16, 18, 46], there is concern on the safety of noninvasive intravenous ergonovine provocative testing, and – according to ESC guidelines 2013 [47] – as fatal complications may occur with intravenous injection of ergonovine, due to prolonged spasm involving multiple vessels, the intracoronary route is preferred.

7 Clinical Guidelines

Provocative testing with intravenous ergonovine is not recommended in patients without known coronary artery anatomy nor in patients with high grade obstructive lesions on coronary arteriography. Diagnostic tests proposed in suspected vasospastic angina are listed in Table 16.2 [47].

In out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, there is no evidence of heart disease in 5 % of patients. In them, according to 1997 guidelines, “ergonovine test during coronary angiography is recommended but not mandatory” [48]. Recent data from the Japanese Coronary Spasm Association suggest a 6 % incidence of coronary vasospasm in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest from cardiac cause [49]. These patients who survived cardiac arrest are a high-risk population in spite of maximal medical therapy and should be identified. This represents about 10 % of indications to ergonovine testing in the stress echo lab [46], but more extensive experience is needed to bring this currently “off-label” indication into guidelines. In the guidelines for diagnosis of coronary spastic angina by the Japanese Circulation Society, drug-induced coronary spasm provocation testing with ergonovine (or acethylcholine) is recommended only with invasive evaluation during cardiac catheterization, with class 1 indication in patients in whom vasospastic angina is suspected on the basis of symptoms, but in whom coronary spasm has not been diagnosed by non-invasive evaluation (including exercise-ECG test, Holter and hyperventilation test) [50].

References

Maseri A (1987) Role of coronary artery spasm in symptomatic and silent myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 9:249–262

Heupler FA Jr, Proudfit WL, Razavi M et al (1978) Ergonovine maleate provocative test for coronary arterial spasm. Am J Cardiol 41:631–640

Yasue H, Horio Y, Nakamura N et al (1986) Induction of coronary artery spasm by acetylcholine in patients with variant angina: possible role of the parasympathetic nervous system in the pathogenesis of coronary artery spasm. Circulation 74:955–963

Yasue H, Nagao M, Omote S et al (1978) Coronary arterial spasm and Prinzmetal’s variant form of angina induced by hyperventilation and Tris-buffer infusion. Circulation 58:56–62

Muller-Schweinitzer E (1980) The mechanism of ergometrine-induced coronary arterial spasm. In vitro studies on canine arteries. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2:645–655

Mantyla R, Kanto J (1981) Clinical pharmacokinetic of methylergometrine (methylergonovine). Int J Clin Pharmacol Biopharm 19:386–391

Heupler FA (1980) Provocative testing for coronary arterial spasm. Risk, method and rationale. Am J Cardiol 46:335–337

Song JK, Park SW, Kim JJ et al (1994) Values of intravenous ergonovine test with two-dimensional echocardiography for diagnosis of coronary artery spasm. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 7:607–615

Song JK, Lee SJK, Kang DH et al (1996) Ergonovine echocardiography as a screening test for diagnosis of vasospastic angina before coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 27:1156–1161

Distante A, Rovai D, Picano E et al (1984) Transient changes in left ventricular mechanics during attacks of Prinzmetal’s angina: an M-mode echocardiographic study. Am Heart J 107:465–474

Distante A, Rovai D, Picano E et al (1984) Transient changes in left ventricular mechanics during attacks of Prinzmetal’s angina: a two-dimensional echocardiographic study. Am Heart J 108:440–446

Distante A, Picano E, Moscarelli E et al (1985) Echocardiographic versus hemodynamic monitoring during attacks of variant angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol 55:1319–1322

Rovai D, Distante A, Moscarelli E et al (1985) Transient myocardial ischemia with minimal electrocardiographic changes: an echocardiographic study in patients with Prinzmetal’s angina. Am Heart J 109:78–83

Morales MA, Lombardi M, Distante A et al (1985) Ergonovine-echo test assess the significance of chest pain at rest without ECG changes. Eur Heart J 16:1361–1366

Song JK, Park SW, Kang DH et al (1998) Diagnosis of coronary vasospasm in patients with clinical presentation of unstable angina using ergonovine echocardiography. Am J Cardiol 82:1475–1478

Song JK, Park SW, Kang DH et al (2000) Safety and clinical impact of ergonovine stress echocardiography for diagnosis of coronary vasospasm. J Am Coll Cardiol 35:1850–1856

Nedeljkovic MA, Ostojic M, Beleslin B et al (2001) Efficiency of ergonovine echocardiography in detecting angiographically assessed coronary vasospasm. Am J Cardiol 88:1183–1187

Palinkas A, Picano E, Rodriguez O et al (2002) Safety of ergot stress echocardiography for noninvasive detection of coronary vasospasm. Coron Artery Dis 12:649–654

Buxton A, Goldberg S, Hirshfeld JW et al (1980) Refractory ergonovine-induced vasospasm: importance of intracoronary nitroglycerin. Am J Cardiol 46:329–334

Pepine CJ, Feldman RJ, Conti CR (1982) Action of intracoronary nitroglycerin in refractory coronary artery spasm. Circulation 65:411–414

Song JK, Park SW, Kang DH et al (2002) Prognostic implication of ergonovine echocardiography in patients with near normal coronary angiogram or negative stress test for significant fixed stenosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 15:1346–1352

Hamilton KK, Pepine CJ (2000) A renaissance of provocative testing for coronary spasm? J Am Coll Cardiol 35:1857–1859

van der Burg AE, Bax JJ, Boersma E et al (2004) Standardized screening and treatment of patients with life-threatening arrhythmias: the Leiden out-of-hospital cardiac arrest evaluation study. Heart Rhythm 1:51–57

Epureanu V, San Román JA, Vega JL et al (2002) Acute pulmonary edema with normal coronary arteries: mechanism identification by ergonovine stress echocardiography. Rev Esp Cardiol 55:775–777

Previtali M, Repetto A, Panigada S et al (2008) Left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: prevalence clinical characteristics and pathogenetic mechanisms in a European population. Int J Cardiol 134:91–96

Lombardi M, Morales MA, Michelassi C et al (1993) Efficacy of isosorbide-5-mononitrate versus nifedipine in preventing spontaneous and ergonovine-induced myocardial ischaemia. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur Heart J 14:845–851

Barinagarrementeria F, Cantú C, Balderrama J (1992) Postpartum cerebral angiopathy with cerebral infarction due to ergonovine use. Stroke 23:1364–1366

Salem DN, Isner JM, Hopkins P et al (1984) Ergonovine provocation in postpartum myocardial infarction. Angiology 35:110–114

Nall KS, Feldman B (1998) Postpartum myocardial infarction induced by Methergine. Am J Emerg Med 16:502–504

Yaegashi N, Miura M, Okamura K (1999) Acute myocardial infarction associated with postpartum ergot alkaloid administration. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 64:67–68

Ribbing M, Reinecke H, Breithardt G et al (2001) Acute anterior wall infarct in a 31-year-old patient after administration of methylergometrine for peripartal vaginal hemorrhage. Herz 26:489–493

Hayashi Y, Ibe T, Kawato H et al (2003) Postpartum acute myocardial infarction induced by ergonovine administration. Intern Med 42:983–986

Ichiba T, Nishie H, Fujinaka W et al (2005) Acute myocardial infarction due to coronary artery spasm after caesarean section. Masui 54:54–56

Larrazet F, Spaulding C, Lobreau HJ et al (1993) Possible bromocriptine-induced myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 118:199–200

Hopp L, Weisse AB, Iffy L (1996) Acute myocardial infarction in a healthy mother using bromocriptine for milk suppression. Can J Cardiol 12:415–418

Castle WM, Simmons VE (1992) Coronary vasospasm and sumatriptan. BMJ 305:117–118

Mueller L, Gallagher RM, Ciervo CA (1996) Vasospasm-induced myocardial infarction with sumatriptan. Headache 36:329–331

Wackenfors A, Jarvius M, Ingemansson R et al (2005) Triptans induce vasoconstriction of human arteries and veins from the thoracic wall. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 45:476–484

Bassi S, Amersey R, Henderson R et al (2004) Thyrotoxicosis, sumatriptan and coronary artery spasm. J R Soc Med 97:285–287

Kleiman NS, Lehane DE, Geyer CE Jr et al (1987) Prinzmetal’s angina during 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy. Am J Med 82:566–568

Lestuzzi C, Viel E, Picano E et al (2001) Coronary vasospasm as a cause of effort-related myocardial ischemia during low-dose chronic continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil. Am J Med 111:316–318

Sestito A, Sgueglia GA, Pozzo C et al (2006) Coronary artery spasm induced by capecitabine. J Cardiovasc Med 7:136–138

Papadopoulos CA, Wilson H (2008) Capecitabine-associated coronary vasospasm: a case report. Emerg Med J 25:307–309

Rezkalla SH, Kloner RA (2007) Cocaine-induced acute myocardial infarction. Clin Med Res 5:172–176

McCord J, Jneid H, Hollander JE et al (2008) American heart association acute cardiac care committee of the council on clinical cardiology. Management of cocaine-associated chest pain and myocardial infarction: a scientific statement from the American heart association acute cardiac care committee of the council on clinical cardiology. Circulation 117:1897–1907

Cortell A, Marcos-Alberca P, Almería C (2010) Ergonovine stress echocardiography: recent experience and safety in our centre. World J Cardiol 2:437–442

Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S et al (2013) 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the task force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J 34:2949–3003

Consensus Statement of the Joint Steering Committees of the Unexplained Cardiac Arrest Registry of Europe and of the Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation Registry of the United States (1997) Survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with apparently normal heart. Need for definition and standardized clinical evaluation. Circulation 95:265–272

Takagi Y, Yasuda S, Tsunoda R et al (2011) Japanese coronary spasm association. Clinical characteristics and long-term prognosis of vasospastic angina patients who survived out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: multicenter registry study of the Japanese coronary spasm association. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 4:295–302

Japanese Cardiovascular Society Joint Working Group (2010) Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of patients with vasospastic angina (coronary spastic angina). Digest version. Circ J 74:1745–1762

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Table of Contents Video Companion

Table of Contents Video Companion

-

See stress echo primer, cases 13 to 16.

-

See also, in the section “Illustrative cases: case number 12” (by Jae-Kwan Song, MD, Seoul, South Korea).

-

See also in selected presentations: Vasospasm in the echo lab: witches are back.

-

Springer Extra Materials available at http://extras.springer.com/2015/978-3-319-20957-9

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Song, JK., Picano, E. (2015). Ergonovine Stress Echocardiography for the Diagnosis of Vasospastic Angina. In: Stress Echocardiography. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20958-6_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20958-6_16

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-20957-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20958-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)