Abstract

The various types of treatment of lymphedema are under discussion, and there has been some controversy regarding liposuction for lymphedema. Although it is clear that conservative therapies such as complex decongestive therapy (CDT) and controlled compression therapy (CCT) should be tried in the first instance, options for the treatment of late-stage lymphedema that is not responding to such treatment is not so clear. Improvements in technique, patient preparation, and patient follow-up have led to a greater and a wider acceptance of liposuction as a treatment for lymphedema. This chapter outlines the benefits of using liposuction and presents the evidence to support its use.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Liposuction

- Suction-assisted lipectomy

- Circumferential suction-assisted lipectomy lymphedema

- Adipose tissue

- Fat

- Inflammation

Key Points

-

Excess arm or leg volume without pitting implies that excess adipose tissue is present.

-

Excess adipose tissue can be removed by the use of liposuction. Conservative treatment and microsurgical reconstructions cannot remove adipose tissue.

-

As in conservative treatment, the lifelong use (24 h a day) of custom made, flat knitted compression garments is mandatory for maintaining the effect of surgery.

-

Patients that are happy with an excess volume in the arm or leg are not candidates for liposuction.

-

Liposuction is a potent therapeutical modality for special indications in persistent primary and secondary lymphedema. The treatment is embedded within a multidisciplinary team and centralized in an expert center.

Introduction

The various types of treatment of lymphedema are under discussion, and there has been some controversy regarding liposuction for lymphedema. Although it is clear that conservative therapies such as complex decongestive therapy (CDT) and controlled compression therapy (CCT) should be tried in the first instance, options for the treatment of late-stage lymphedema that is not responding to such treatment is not so clear. Improvements in technique, patient preparation, and patient follow-up have led to a greater and a wider acceptance of liposuction as a treatment for lymphedema. This chapter outlines the benefits of using liposuction and presents the evidence to support its use.There is an increasing body of evidence, based on well-controlled clinical trials and long-term follow-up, that liposuction can result in significant objective and subjective benefit to patients who have long-term chronic lymphedema [1, 2]. There are, however, different views on the immediate, short-term, and long-term benefits of liposuction for treating lymphedema, with a strong dichotomy between those who support surgical and conservative treatments.

Excess Subcutaneous Adiposity and Chronic Lymphedema

The incidence of post-mastectomy arm lymphedema varies between 6 and 49 %, depending on the combination of therapy, including mastectomy, sentinel node biopsy, standard axillary lymph node dissection, and/or postoperative irradiation [3–5].

The outcome of the surgical procedure as well as of the irradiation of the tissue often results in the destruction of lymphatic vessels. When this is combined with the removal of lymph nodes and tissue scarring, the lymphatic vessels that remain are likely to be unable to remove the load of lymph. The remaining lymph collectors become dilated and overloaded and their valves become incompetent, preventing the lymphatics from performing their function. This failure spreads distally until even the most peripheral lymph vessels, draining into the affected system, also become dilated [6].

The enlargement of the arm leads to discomfort and complaints in the form of heaviness, weakness [7], pain, tension, and a sensory deficit of the limb, as well as anxiety, psychological morbidity, maladjustment, and social isolation [8, 9], and increasing hardness of the limb [10]. In time, there is also an increase in the adipose tissue content of the swollen arm. We have observed this clinically since 1987, when the first lymphedema patient was operated on [11, 12]. Figure 28.1 shows a picture of excess fat volume in the lymphedematous arm taken in the 1960s; still this phenomenon was never brought up in the literature.

Presently there is no cure for lymphedema. With early diagnosis, the majority of patients can be treated by conservative treatment, such as complex decongestive therapy (CDT) [13], which comprises manual lymph drainage, compression therapy, physical exercise, skin care and self-management, followed by wearing flat knitted compression garments. The effect of CDT on long-standing massive edema with excess adipose tissue is poor, since adipose tissue does not disappear by means of compression alone. In addition, surgical intervention is reserved for patients with excess volume and heaviness causing severe strain in the shoulder and neck, functional impairment, recurrent attacks of erysipelas, and problems with clothing fit.

For the treatment of late-stage lymphedema that does not respond to conservative treatment, liposuction combined with postoperative, lifelong effective compression therapy has become a viable alternative. Postoperative follow-up and regular adjustment of the compression technology is mandatory.

There are various possible explanations for the adipose tissue hypertrophy. There is a physiological imbalance of blood flow and lymphatic drainage, resulting in the impaired clearance of lipids and their uptake by macrophages [14]. However, there is increasing support, for the view that the fat cell is not simply a container of fat, but is an endocrine organ and a cytokine-activated cell [15, 16] and that chronic inflammation plays a role here [15, 17]. The same pathophysiology applies for primary and secondary leg lymphedema. Recent research showed a relationship between slow lymph flow and adiposity, as well as that between structural changes in the lymphatic system and adiposity [18, 19].

From a more clinical view, other indications for adipose tissue hypertrophy have been found:

-

Consecutive analyses of the content of the aspirate by the author, removed under bloodless conditions using a tourniquet, showed a very high content of adipose tissue in 44 women with post-mastectomy arm lymphedema (mean 90 %, range 58–100) [20]. This has been confirmed by Damstra et al.’s [21] study of 37 patients with end-stage breast cancer related lymphedema where the proportion of fat in the aspirate (when a tourniquet was used) was 93 % (range 59–100 %). The same outcome was shown in a study by Schaverien et al. in 12 patients with arm lymphedema following breast cancer treatment with 92 % (range, 75–100) of fat in the aspirate [22].

-

Analyses with dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in 18 women with arm lymphedema following a mastectomy showed a significant increase of adipose (73 %) and muscle tissue (47 %), and even bone mineral content (7 %) in the non-pitting swollen arm before surgery. The greater weight of the affected arm leads to a higher mechanical load on both the muscle and the skeleton, resulting in increased muscle and bone mass. There was no correlation between the duration of lymphedema and the amount of excess adipose, muscle, or bone tissue. This indicates that the increase in soft tissue volume develops when the lymphedema appears or soon thereafter [23].

-

Preoperative investigation with volume-rendered computer tomography (VRCT) in 11 women showed a significant preoperative increase of adipose tissue in the swollen arm, the excess volume consisting of 81 % (range 68–96) fat [24].

-

Tonometry findings in 20 women with post-mastectomy arm lymphedema showed postoperative changes in the upper arm, but not in the forearm, which also showed significantly higher absolute values than in the upper arm. This is probably caused by the high adipose tissue content with little or no free fluid, as in the normal arm. The thinner subcutaneous tissue in the forearm may also play a part [25].

-

The findings of increased adipose tissue in intestinal segments in patients with Crohn’s disease, known as “fat wrapping,” have clearly shown that inflammation plays an important role [17, 26, 27].

-

A major problem in Graves’s ophthalmopathy is an increase in the intraorbital adipose tissue volume leading to exophthalmos. Overexpression of adipocyte-related immediate early genes in active ophthalmopathy and cysteine-rich, angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61) may have a role in both orbital inflammation and adipogenesis and serve as a marker of disease activity [28].

-

Recent research had showed that adipogenesis in response to lymphatic fluid stasis was associated with a marked mononuclear cell inflammatory response [29], and that lymphatic fluid stasis potently upregulates the expression of fat differentiation markers both spatially and temporally [30].

The common understanding among clinicians is that the swelling of a lymphedematous extremity is due purely to the accumulation of lymph fluid, which can be removed by use of noninvasive conservative regimens such as CDT.

Microsurgery and lympho-venous anastomosis (LVA) have been studied for a long time without convincing results [31]. Although the LVA has been performed and studied for more than three decades, this method still has not had a breakthrough and will never become a treatment of choice in daily practice. In a large overview article by Campisi et al. [32], a positive effect was described in early stages of lymphedema. However, for later, more irreversible stages, this therapeutic option was not suitable. Moreover, a recent study showed that the net effect of LVA was minor and that the outcome was due to the CDT performed preoperatively and postoperatively [33].

Brorson et al. [12] concluded that when the excess volume is dominated by adipose tissue, supra-facial clearance by liposuction is the only method to achieve up to 100 % excess volume reduction.

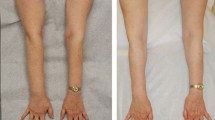

Today, chronic non-pitting arm lymphedema of up to 4 l in excess can be effectively removed by use of liposuction and compression therapy, without any further reduction in lymph transport [34]. Long-term results, up to 15 years, have not shown any recurrence of the arm swelling. Complete reduction is mostly achieved in between 3 and 6 months, often earlier (see Figs. 28.2 and 28.3) [12, 35].

In 2009 Damstra et al. [21] reproduced these results in a large study with 37 breast cancer-related lymphedema patients. A recent publication from 2012 with a 5-year follow-up in 12 patients with breast cancer related lymphedema confirmed no recurrence with this technique [22]. Promising results can also be achieved for leg lymphedema, for which complete reduction is usually reached at around 6 months (see Figs. 28.4a, b) [36, 37].

(a) Secondary lymphedema: Preoperative excess volume 7,070 ml (left). Postoperative result after 6 months where excess volume is –445 ml, i.e., the treated leg is somewhat smaller than the normal one (right). © Håkan Brorson. (b) Primary lymphedema: Preoperative excess volume 6,630 ml (left). Postoperative result after 2 years where excess volume is 30 ml (right). © Håkan Brorson

Liposuction

Surgical Technique

Made-to-measure compression garments (two sleeves and two gloves) are measured and ordered 2 weeks before surgery, using the healthy arm and hand as a template. Nowadays we use power-assisted liposuction because the vibrating cannula facilitates the liposuction, especially in the leg, which is more demanding to treat. Initially the “dry technique” was used [38]. Later, to minimize blood loss, a tourniquet was utilized in combination with tumescence, which involves infiltration of 1–2 l of saline containing low-dose adrenaline and lignocaine [39, 40].

Through approximately 10–15, 3-mm-long incisions, liposuction is performed using 15- and 25-cm-long cannulas with diameters of 3 and 4 mm (see Figs. 28.5 and 28.6). Liposuction is executed circumferentially, step-by-step from wrist to shoulder, and the hypertrophied fat is removed as completely as possible (see Figs. 28.5, 28.6, and 28.7).

(a) Preoperative picture showing a patient with a large lymphedema (2,865 ml) and decreased mobility of the right arm. © Håkan Brorson. (b) The cannula lifts the loose skin of the treated forearm. (c) The distal half of the forearm has been treated. Note the sharp border between treated (distal forearm) and untreated (proximal arm) area. © Håkan Brorson

The aspirate contains 90–100 % adipose tissue in general. This picture shows the aspirate collected from the lymphedematous arm of the patient shown in Figs. 28.4, 28.5, and 28.7 before removal of the tourniquet. The aspirate sediments into an upper adipose fraction (90 %) and a lower fluid (lymph) fraction (10 %). © Håkan Brorson

When the arm distal to the tourniquet has been treated, a sterilized made-to-measure compression sleeve is applied (Jobst¨ Elvarex BSN medical, compression class 2) to the arm to stem bleeding and reduce postoperative edema. A sterilized, standard interim glove (Cicatrex interim, Thuasne¨, France) in which the tips of the fingers have been cut to facilitate gripping, is put on the hand. The tourniquet is removed and the most proximal part of the upper arm is treated using the tumescent technique [39, 40]. Finally, the proximal part of the compression sleeve is pulled up to compress the proximal part of the upper arm. The incisions are left open to drain through the sleeve. The arm is lightly wrapped with a large absorbent compress covering the whole arm (60 × 60 cm, Cover-Dri, www.attends.co.uk). The arm is kept at heart level on a large pillow. The compress is changed when needed.

The following day, a standard gauntlet (i.e., a glove without fingers, but with a thumb; Jobst Elvarex compression class 2) is put over the interim glove after the thumb of the gauntlet has been cut off to ease the pressure on the thumb. If the gauntlet is put on straight after surgery, it can exert too much pressure on the hand when the patient is still not able to move the fingers after the anesthesia. Operating time is, on average, 2 h. An isoxazolylpenicillin or a cephalosporin is given intravenously for the first 24 h and then in tablet form until incisions are healed, about 10–14 days after surgery. Liposuction technique for leg lymphedema is similar to that for the arm.

Postoperative Care

Garments are removed 2 days postoperatively so that the patient can take a shower. Then, the other set of garments is put on and the used set is washed and dried. The patient repeats this after another 2 days before discharge. The standard glove and gauntlet is usually changed to the made-to-measure glove at the end of the hospital stay (Fig. 28.8).

The compression garment is removed two days after surgery so that the patient can take a shower. When bandages are used, at the first bandage change, made-to-measure, flat knitted garment are measured and ordered. Then, the other set of garments is put on and the used set is washed and dried or the arm is re-bandaged. A significant reduction of the right arm has been achieved, as compared with the preoperative condition seen in Fig. 28.6a. © Håkan Brorson

The patient alternates between the two sets of garments (1 set = 1 sleeve and 1 glove) during the 2 weeks postoperatively, changing them daily or every other day so that a clean set is always put on after showering and lubricating the arm. After the 2-week control, the garments are changed every day after being washed. Washing “activates” the garment by increasing the compression due to shrinkage.

Controlled Compression Therapy (CCT)

A prerequisite to maintaining the effect of liposuction and, for that matter, conservative treatment, is the continuous use of a compression garment [12]. Compression therapy is crucial, and its application is therefore thoroughly described and discussed at the first clinical evaluation. If the patient has any doubts about continued CCT, she is not accepted for treatment. After initiating compression therapy, the custom-made garment is taken in, when needed, at each visit using a sewing machine, to compensate for reduced elasticity and reduced arm volume.

This is most important during the first 3 months when the most notable changes in volume occur. At the 1- and 3-month visits, the arm is measured for new custom-made garments (two sets). This procedure is repeated at 6, (9), and 12 months. If complete reduction has been achieved at 6 months, the 9-month control may be omitted. If this is the case, remember to prescribe garments for 6 months, which normally means double the amount than would be needed for 3 months. It is important, however, to take in the garment repeatedly to compensate for wear and tear.

This may require additional visits in some instances, although the patient can often make such adjustments herself. When the excess volume has decreased as much as possible and a steady state is achieved, new garments can be prescribed using the latest measurements. In this way, the garments are renewed three or four times during the first year. Two sets of sleeve-and-glove garments are always at the patient’s disposal; one being worn while the other is washed. Thus, a garment is worn permanently, and treatment is interrupted only briefly when showering and, possibly, for formal social occasions. The patient is informed about the importance of hygiene and skin care, as all patients with lymphedema are susceptible to infections, and keeping the skin clean and soft is a prophylactic measure [11, 12].

The life span of two garments worn alternately is usually 4–6 months. Complete reduction is usually achieved after 3–6 months, often earlier. After the first year, the patient is seen again after 6 months (1.5 years after surgery) and then at 2 years after surgery. Then the patient is seen once a year only, when new garments are prescribed for the coming year, usually four garments and four gloves (or four gauntlets). For very active patients, six to eight garments and the same amount of gauntlets/gloves a year are needed. Patients without preoperative swelling of the hand can usually stop using the glove/gauntlet after 6–12 months postoperatively.

For legs, the author’s team often uses up to two, sometimes three compression garments, on top of each other, depending on what is needed to prevent pitting. A typical example is Elvarex¨ compression class 3 (or 3 Forte), and Elvarex¨ compression class 2 (BSN Medical); the latter being a below-the-knee garment. Sometimes a leg-long Jobst Bellavar¨ compression class 2 (or Elvarex¨ compression class 2) is added when needed. Thus, such a patient needs two sets of two to three garments/set. One set is worn while the other is washed. Depending on the age and activity of the patient, two such sets usually lasts for (2–)4 months. That means that they must be prescribed 3(–6) times during the first year. After complete reduction has been achieved, usually at around 6 months, the patient is seen once a year when all new garments are prescribed for the coming year. During night only one leg-long garment is used.

CCT can also be used primarily to effectively treat a pitting edema as an alternative to CDT, which, in contrast to CCT, comprises daily interventions [12] (see Chap. 18).

Arm Volume Measurements

Arm volumes are recorded for each patient using the water displacement technique. The displaced water is weighed on a balance to the nearest 5 g, corresponding to 5 mL. Both arms are always measured at each visit, and the difference in arm volumes is designated as the edema volume. The decrease in the edema volume is calculated in a percentage of the preoperative value [11].

The Lymphedema Team

To investigate and treat patients with lymphedema, a team comprising a plastic surgeon, an occupational therapist, a physiotherapist, and a social welfare officer is needed. An hour is reserved for each scheduled visit to the team when arm volumes are measured, garments are adjusted or renewed, the social circumstances are assessed, and other matters of concern are discussed.

The patient is also encouraged to contact the team whenever any unexpected problems arise, so that these can be tackled without delay. In retrospect, a working group such as this one seems to be a prerequisite both for thorough preoperative consideration and informing patients and for successful maintenance of immediate postoperative improvements. The team also monitors the long-term outcome, and the authors’ experience so far indicates that a visit once a year is necessary, in most cases, to maintain a good functional and cosmetic result after complete reduction.

Why Does Liposuction Help?

If the lymphedema is treated immediately by conservative regimens, the swelling can disappear. If not, or improperly treated, the swelling increases in time and can end up in an even larger pitting edema with concomitant adipose tissue formation, which starts early when the lymphedema appears or soon thereafter [23].

For many patients with lymphedema conservative treatment does not work well or come up to their expectations, and no matter what therapy they receive, neither conservative treatment nor microsurgical procedures can remove excess adipose tissue [31–33, 41–44]. Subcutaneous tissue debulking seems the only option to reduce the limb volume and lead to an improvement in the patient’s quality of life [10].

Lymph Transport System and Liposuction

To investigate the effect of liposuction on lymph transport, the authors conducted an investigation using indirect lymphoscintigraphy in 20 patients with post-mastectomy arm lymphedema. Scintigraphies were performed before liposuction, with and without wearing a garment. This was repeated after 3 and 12 months. In conclusion, it was found that the already decreased lymph transport was not further reduced after liposuction [34].

When to Use Liposuction to Treat Lymphedema

Especially for more extended stages of lymphedema with irreversible changes; nonoperative treatment will give inappropriate reduction of volume and complaints. For these people conservative treatment does not work well or come up to their expectations, and no matter what therapy they receive, neither conservative treatment nor microsurgical procedures can remove excess adipose tissue [31–33, 41–44]. Subcutaneous tissue debulking seems the only option to reduce the limb volume and to lead to an improvement in the patient’s quality of life. As patients treated by conservative treatment also need a life garment, this issue is the same for both groups.

A surgical approach, with the intention of removing the hypertrophied adipose tissue, seems logic when conservative treatment has not achieved satisfactory edema reduction and the patient has subjective discomfort of a heavy arm. This condition is especially seen in chronic, large arm lymphedema around 1 l in volume, or when the volume ratio (edematous arm/healthy arm) is 1.3.

Contraindications for Liposuction

Liposuction should never be performed in a patient who is not maximal conservatively treated. Clinical features show pits on pressure (Fig. 28.9a). In a patient with an arm lymphedema, the author accepts around 4–5 mm of pitting, and in a leg lymphedema 6–7 mm. Patients with more pitting should be treated conservatively until the pitting has been reduced. The reason for not doing liposuction in a pitting edema is that liposuction is a method to remove fat, not fluid, even if theoretically it could remove all the accumulated fluid in a pitting lymphedema without excess adipose tissue formation.

(a) Marked lymphedema of the arm after breast cancer treatment, showing pitting several centimeters in depth (grade I edema). The arm swelling is dominated by the presence of fluid, i.e., the accumulation of lymph. © Håkan Brorson. (b) Pronounced arm lymphedema after breast cancer treatment (grade II edema). There is no pitting in spite of hard pressure by the thumb for 1 min. A slight reddening is seen at the two spots where pressure has been exerted. The “edema” is completely dominated by adipose tissue. The term “edema” is improper at this stage since the swelling is dominated by hypertrophied adipose tissue and not by lymph. At this stage, the aspirate contains either no, or a minimal amount of lymph. © Håkan Brorson

Other contraindications for liposuction are:

-

Metastatic disease or open wounds

-

Medical or family history of coagulation disorders or intake of drugs that affect coagulation

-

Physically not fit for surgery

-

Patient reluctant to wear compression garments continuously after surgery

The first and most important goal is to transform a pitting edema into a non-pitting one by conservative regimens such as CDT or CCT. “Pitting” means that a depression is formed after pressure on the edematous tissue by the fingertip, resulting in lymph being squeezed into the surroundings (see Fig. 28.9a). To standardize the pitting test, one presses as hard as possible with the thumb on the region to be investigated for 1 min, the amount of depression being estimated in millimeters. A swelling that is dominated by hypertrophied adipose tissue shows little or no pitting (see Fig. 28.9b) [45].

Stemmer’s sign implies that you can pinch the skin at the base of the toes or fingers with difficulty or not at all. This is due to increased fibrosis and is characteristic for chronic lymphedema. On the other hand, a negative sign does not exclude lymphedema. The author has not seen any relationship between either a positive or negative sign and the occurrence of adipose tissue.

When a patient has been treated conservatively and shows no pitting, liposuction can be performed. If quality of life is low, this can be especially effective. The cancer itself is a worry, but the swollen and heavy arm introduces an additional handicap for the patient from a physical, psychosocial, and psychological point of view. Physical problems include pain, limited limb movement, and physical mobility and problems with clothing, thus interfering with everyday activities. Also, the heavy and swollen arm is impractical and cosmetically unappealing, all of which contribute to emotional distress [10].

Benefits to the Patient

Liposuction improves patients’ quality of life, particularly qualities associated with everyday activities, and hence those that can be directly related to the complete arm edema reduction [10]. CCT is also beneficial, but the effect is less obvious than when combined with surgery, conceivably because the reduction of excess volume is less [12].

Skin blood flow and cellulitis after liposuction reduces the incidence of erysipelas; the annual incidence of cellulitis was 0.4 before liposuction and 0.1 after. Improved local skin blood flow may be an important contributing factor to the reduced episodes of arm infection [46]. The point of bacterial entry may be a minor injury to the edematous skin, and impaired skin blood flow may respond inadequately to counteract impending infection. Reducing the excess volume by liposuction increases skin blood flow in the arm, and decreases the reservoir of adipose tissue, which may enhance bacterial overgrowth.

Potential Negative Effects to the Patient

Liposuction typically leads to numbness in the skin, which disappears within 3–6 months. Continuous, that is, lifelong wearing of compression garments is a prerequisite of maintaining the effect of any lymphedema treatment and should not be considered as a negative effect.

Conclusion

Liposuction combined with permanent compression therapy is a proven effective treatment. The technique can be a potent therapeutic modality within an integrated, multidisciplinary lymphological care program. Accumulated lymph should be initially removed using the well-documented conservative regimens until minimal or no pitting is seen. If there is still a significant excess volume, this can be removed by the use of liposuction. In some patients increased fibrous tissue can be present, especially in male patients and in women with a male distribution of body fat. When seen, fibrous tissue is more common in leg than in arm lymphedema, and more common in men than in women. Continuous wearing of a compression garment prevents recurrence.

References

Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Svensson B. Liposuction of leg lymphedema: preliminary 2 year results. Lymphology. 2007;40(Suppl):250–2.

Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Svensson B. Long term cosmetic and functional results following liposuction for arm lymphedema: an eleven year study. Lymphology. 2007;40(Suppl):253–5.

Segerstrom K, Bjerle P, Graffman S, Nystrom A. Factors that influence the incidence of brachial oedema after treatment of breast cancer. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1992;26(2):223–7.

Petrek JA, Senie RT, Peters M, Rosen PP. Lymphedema in a cohort of breast carcinoma survivors 20 years after diagnosis. Cancer. 2001;92(6):1368–77.

Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, Goyal A, Newcombe RG, Dixon JM, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(9):599–609.

Olszewski WL. Lymph stasis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. 1st ed. Boca Raton: CRC; 1991. p. 648.

Johansson K, Piller N. Weight-bearing exercise and its impact on arm lymphoedema. J Lymphoedema. 2007;2(1):15–22.

Ridner SH. Quality of life and a symptom cluster associated with breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(11):904–11.

Piller NB, Thelander A. Treatment of chronic postmastectomy lymphedema with low level laser therapy: a 2.5 year follow-up. Lymphology. 1998;31(2):74–86.

Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Långström G, Wiklund I, Svensson H. Quality of life following liposuction and conservative treatment of arm lymphedema. Lymphology. 2006;39(1):8–25.

Brorson H, Svensson H. Complete reduction of lymphoedema of the arm by liposuction after breast cancer. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1997;31(2):137–43.

Brorson H, Svensson H. Liposuction combined with controlled compression therapy reduces arm lymphedema more effectively than controlled compression therapy alone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(4):1058–67. discussion 68.

Rockson SG, Miller LT, Senie R, Brennan MJ, Casley-Smith JR, Foldi E, et al. American Cancer Society Lymphedema Workshop. Workgroup III: diagnosis and management of lymphedema. Cancer. 1998;83(12):2882–5.

Ryan TJ. Lymphatics and adipose tissue. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13(5):493–8.

Sadler D, Mattacks CA, Pond CM. Changes in adipocytes and dendritic cells in lymph node containing adipose depots during and after many weeks of mild inflammation. J Anat. 2005;207(6):769–81.

Pond CM. Adipose tissue and the immune system. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73(1):17–30.

Borley NR, Mortensen NJ, Jewell DP, Warren BF. The relationship between inflammatory and serosal connective tissue changes in ileal Crohn’s disease: evidence for a possible causative link. J Pathol. 2000;190(2):196–202.

Harvey NL, Srinivasan RS, Dillard ME, Johnson NC, Witte MH, Boyd K, et al. Lymphatic vascular defects promoted by Prox1 haploinsufficiency cause adult-onset obesity. Nat Genet. 2005;37(10):1072–81.

Schneider M, Conway EM, Carmeliet P. Lymph makes you fat. Nat Genet. 2005;37(10):1023–4.

Brorson H, Åberg M, Svensson H. Chronic lymphedema and adipocyte proliferation: clinical therapeutic implications. Lymphology. 2004;37(Suppl):153–5.

Damstra RJ, Voesten HG, Klinkert P, Brorson H. Circumferential suction-assisted lipectomy for lymphoedema after surgery for breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96(8):859–64.

Schaverien MV, Munro KJ, Baker PA, Munnoch DA. Liposuction for chronic lymphoedema of the upper limb: 5 years of experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(7):935–42.

Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Karlsson MK. Breast cancer-related chronic arm lymphedema is associated with excess adipose and muscle tissue. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7(1):3–10.

Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Nilsson M. Adipose tissue dominates chronic arm lymphedema following breast cancer: an analysis using volume rendered CT images. Lymphat Res Biol. 2006;4(4):199–210.

Bagheri S, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Brorson H. Tissue tonometry before and after liposuction of arm lymphedema following breast cancer. Lymphat Res Biol. 2005;3(2):66–80.

Jones B, Fishman EK, Hamilton SR, Rubesin SE, Bayless TM, Cameron JC, et al. Submucosal accumulation of fat in inflammatory bowel disease: CT/pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986;10:759–63.

Sheehan AL, Warren BF, Gear MW, Shepherd NA. Fat-wrapping in Crohn’s disease: pathological basis and relevance to surgical practice. Br J Surg. 1992;79(9):955–8.

Lantz M, Vondrichova T, Parikh H, Frenander C, Ridderstrale M, Asman P, et al. Overexpression of immediate early genes in active Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4784–91.

Zampell JC, Aschen S, Weitman ES, Yan A, Elhadad S, De Brot M, et al. Regulation of adipogenesis by lymphatic fluid stasis: part I. Adipogenesis, fibrosis, and inflammation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(4):825–34.

Aschen S, Zampell JC, Elhadad S, Weitman E, De Brot M, Mehrara BJ. Regulation of adipogenesis by lymphatic fluid stasis: part II. Expression of adipose differentiation genes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(4):838–47.

Damstra RJ, Voesten HG, van Schelven WD, van der Lei B. Lymphatic venous anastomosis (LVA) for treatment of secondary arm lymphedema. A prospective study of 11 LVA procedures in 10 patients with breast cancer related lymphedema and a critical review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113(2):199–206.

Campisi C, Bellini C, Campisi C, Accogli S, Bonioli E, Boccardo F. Microsurgery for lymphedema: clinical research and long-term results. Microsurgery. 2010;30(4):256–60.

Maegawa J, Hosono M, Tomoeda H, Tosaki A, Kobayashi S, Iwai T. Net effect of lymphaticovenous anastomosis on volume reduction of peripheral lymphoedema after complex decongestive physiotherapy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43(5):602–8.

Brorson H, Svensson H, Norrgren K, Thorsson O. Liposuction reduces arm lymphedema without significantly altering the already impaired lymph transport. Lymphology. 1998;31(4):156–72.

Brorson H. From lymph to fat: liposuction as a treatment for complete reduction of lymphedema. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2012;11(1):10–9.

Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Svensson B, Svensson H. Controlled compression and liposuction treatment for lower extremity lymphedema. Lymphology. 2008;41(2):52–63.

Brorson HFC, Ohlin K, Svensson B, Åberg M, Svensson H. Liposuction normalizes elephantiasis of the leg—a prospective study with an eight-year follow-up. Lymphology. 2012;45(Suppl):292–5.

Clayton DN, Clayton JN, Lindley TS, Clayton JL. Large volume lipoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1989;16(2):305–12.

Klein JA. The tumescent technique for lipo-suction surgery. Am J Cosmet Surg. 1987;4(4):263–7.

Wojnikow S, Malm J, Brorson H. Use of a tourniquet with and without adrenaline reduces blood loss during liposuction for lymphoedema of the arm. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2007;43(5):1–7.

Baumeister RG, Siuda S. Treatment of lymphedemas by microsurgical lymphatic grafting: what is proved? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85(1):64–74. discussion 5–6.

Andersen L, Hojris I, Erlandsen M, Andersen J. Treatment of breast-cancer-related lymphedema with or without manual lymphatic drainage—a randomized study. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(3):399–405.

Campisi C, Davini D, Bellini C, Taddei G, Villa G, Fulcheri E, et al. Lymphatic microsurgery for the treatment of lymphedema. Microsurgery. 2006;26(1):65–9.

Baumeister RG, Frick A. [The microsurgical lymph vessel transplantation]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2003;35(4):202–9.

Brorson H. Liposuction in arm lymphedema treatment. Scand J Surg. 2003;92(4):287–95.

Brorson H, Svensson H. Skin blood flow of the lymphedematous arm before and after liposuction. Lymphology. 1997;30(4):165–72.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Brorson, H., Svensson, B., Ohlin, K. (2015). Suction-Assisted Lipectomy. In: Greene, A., Slavin, S., Brorson, H. (eds) Lymphedema. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14493-1_28

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14493-1_28

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-14492-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-14493-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)