Abstract

Since biblical times, the labor process has been recognized as being one of the most painful human experiences. Early treatments varied widely, according to the cultural and religious practices of the time. In the middle ages, treatments such as amulets, magic girdles, and readings from the Christian liturgy were considered to be appropriate treatment. More invasive pharmacologic treatments such as the use of soporific sponges (a mixture of biologically active plants, inhaled or ingested) were sufficiently potent to cause unconsciousness. Of interest, bloodletting was used until the middle of the nineteenth century to cause swooning and thus pain relief [1]

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Epidural Analgesia

- Clinical Question

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

- Motor Block

- Instrumental Delivery

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

21.1 Introduction

Since biblical times, the labor process has been recognized as being one of the most painful human experiences. Early treatments varied widely, according to the cultural and religious practices of the time. In the middle ages, treatments such as amulets, magic girdles, and readings from the Christian liturgy were considered to be appropriate treatment. More invasive pharmacologic treatments such as the use of soporific sponges (a mixture of biologically active plants, inhaled or ingested) were sufficiently potent to cause unconsciousness. Of interest, bloodletting was used until the middle of the nineteenth century to cause swooning and thus pain relief [1].

Physicians and midwives that wished to relieve labor pain had to overcome a number of obstacles. Pain, although severe, was known to be self-limited and was not thought to be inherently dangerous to the health of the mother and newborn. In contrast, many treatments of the day carried significant risks to both. It is small wonder that a non- interventional approach was preferred.

Over the last 100 years, pain relief options have become safer and more effective. It became clear that medications that are given to the mother may influence the course of labor and may depress the baby at the time of delivery. Regional analgesia became an important method of providing effective pain relief. However, questions persisted about the effect on the progress of labor and subtle changes in the newborn. Often, fears of harm are based on poorly designed studies that were more likely to demonstrate the researchers’ biases than truth.

In this chapter, we will review the evidence base for providing labor analgesia. We will begin with a definition of “evidence-based medicine.” We will then discuss how to formulate a clinical question and to formulate a plan for best practice. Finally, we will discuss some of the topics that have a clear evidence base and areas for future research.

21.2 Evidence-Based Medicine

21.2.1 Definition

Evidence-based medicine is “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” [2]. This approach must take the available clinical expertise and experience into account. In addition, patient preferences and expectations must be integrated into the process.

21.2.2 How to Use an Evidence-Based Approach

This approach can be broken down into four well-defined steps.

21.2.2.1 Ask a Clinical Question

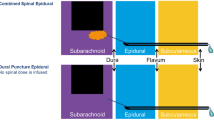

Often, one is faced with a patient with a clinical condition that requires treatment. When considering labor analgesia, one is faced with a number of choices each with different advantages and disadvantages depending on the patient’s expectations, skills, and preferences of the healthcare providers, resources available and other considerations. The “PICO” format is often used as a template to help formulate the question. When considering labor analgesia, the Population must be considered. Are the subjects nulliparous, multiparous, or mixed? Are they healthy or are there obstetric or medical factors that place the patients at risk for adverse outcome? The setting (private vs. public, academic vs. community) should also be considered. The Intervention is usually the experimental treatment. Examples might be method of initiation of analgesia (combined spinal/epidural, epidural alone), timing of the analgesia (early in labor or later), or drug used (ropivacaine, bupivacaine). The Comparator is the control. It is rare for placebo to be used as a comparator in this setting except for some non- pharmacologic treatments such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) or intradermal sterile water injections [3, 4]. In other trials, the control is almost always at least thought to be active. It could be parenteral opioid analgesia, a different form of regional block, or a different mode of maintaining analgesia. The main Outcomes should be clearly defined. Often, when drugs are compared, the main outcome is a measure of quality of analgesia. Sometimes, the main outcome is a particular side effect (operative delivery, motor block, nausea) or benefit (cord pH, maternal satisfaction). An example of how the PICO format could be used to help formulate a treatment plan is shown in Table 21.1.

When designing a clinical trial, the best type of study (randomized controlled trial, cohort study, etc.) will depend on the clinical question and feasibility. Therefore, the “PICOT” format (with the “T” for Type of study) is often used to formulate research questions.

21.2.2.2 Search for the Best Evidence

Once the clinical question has been formulated, the next step is to search for the most reliable information available. A hierarchy of evidence has been formulated, with information at the highest level being (theoretically) the least susceptible to bias. In general, the hierarchy of evidence is shown in Table 21.2.

The type of information available will depend on the exact question. For example, the question posed in Table 21.1 describes two treatments (early vs. late epidural analgesia) and asks about common treatment harms (cesarean section). In that case, the most reliable information, as shown in Table 21.2, is a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. However, questions concerning diagnostic tests (e.g. will a test dose before epidural labor analgesia prevent harm?), or prognosis (e.g. what is the natural history of dural puncture headache with a large gauge needle?), may require other types of information. A summary of the hierarchy of evidence, depending on the clinical question, has recently been published [7]. However, the hierarchy in Table 21.2 pertains to the most common issues in labor analgesia therapy.

21.2.2.3 Critically Appraise and Combine the Evidence

Fortunately, clinicians rarely have to rely on individual studies to formulate a treatment plan. Many topics related to pain relief in labor have recently been systematically reviewed and are available in evidence-based guidelines [8, 9]. These are examples of guidelines that were created using recognized methodology by experts in the field and tested for validity by clinicians. In addition to making recommendations, the strength of the recommendations, using a modification of Table 21.2, is also reported. These guidelines are updated periodically to take into account new information.

21.2.2.4 Determine the Best Treatment for Your Patient

While randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews can often be used as a guide to treatment, they do not give the whole picture. Factors such as the expertise of the clinician, expectations of the patient, and the resources available must also be considered when treating individual patients. For example, epidural analgesia initiated with a low concentration of local anesthetic may reduce the incidence of instrumental vaginal delivery [10], but it may not be the best treatment for a patient with rapidly progressing labor.

21.3 Topics in Analgesia for Labor with Systematic Review or Large RCT Support (Level 1)

There have been many randomized controlled trials that help guide practice in providing labor analgesia for our patients. Some are quite large and definitive, while others are small and yield a less precise estimate of effect. Taken together in a systematic review, a consistent pattern often emerges. Table 21.3 summarizes some of the questions that have been thoroughly studied and have level 1 evidence to support recommendations.

21.4 Conclusions

The optimal provision of analgesia in labor requires application of evidence-based medicine, “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.” This involves four steps:

-

(1)

Asking a clinical question; the “PICO” format can be used as a template where the clinician considers the Population, the Intervention, the Comparator, and the Outcomes when formulating a question.

-

(2)

Searching for the best evidence; this will depend on the exact question formulated. There are established hierarchies of evidence based on study design which guide clinicians in determining the most suitable evidence base.

-

(3)

Critically appraising and combining the evidence; systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and evidence-based guidelines can provide clinicians with useful combined results and recommendations from a broad evidence base.

-

(4)

Determining the best treatment for specific patients taking into consideration their unique characteristics or clinical situations.

There are a number of topics in labor analgesia which have been extensively studied, with high level evidence available to support clinical practice. Neuraxial regional analgesia remains the most effective available modality for labor pain relief. Epidural analgesia does not increase the risk of cesarean delivery, although the second stage of labor may be prolonged, and there may be an increased risk of instrumental delivery. Epidural analgesia may be provided early in labor without affecting labor outcome. Although systemic opioids and nitrous oxide have some analgesic efficacy and may be considered if neuraxial techniques are contraindicated, they are less effective and can cause significant maternal adverse effects. There is little evidence to suggest that non- pharmacological techniques of analgesia (e.g., TENS, acupuncture, sterile water injections) are efficacious.

When initiating neuraxial analgesia, there is little difference between a combined spinal–epidural technique and epidural technique alone. Low concentrations of local anesthetic (e.g., ≤0.1 % bupivacaine) should be used for maintenance of analgesia to reduce the risks of motor block and instrumental delivery. Either ropivacaine or bupivacaine used at low concentrations can be safely and effectively used for epidural analgesia. PCEA along with background infusion is an effective and safe maintenance strategy. There is developing evidence that intermittent mandatory boluses may be superior to continuous infusion when combined with PCEA for maintenance of epidural analgesia; however, further research is required in this area.

References

Mander R (1998) Analgesia and anaesthesia in childbirth: obscurantism and obfuscation. J Adv Nurs 28:86– 93

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS (1996) Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 312:71– 72

Chao AS, Chao A, Wang TH et al (2007) Pain relief by applying transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on acupuncture points during the first stage of labor: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Pain 127:214– 220

Bahasadri S, Ahmadi-Abhari S, Dehghani-Nik M, Habibi GR (2006) Subcutaneous sterile water injection for labour pain: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 46:102– 106

Wong CA, Scavone BM, Peaceman AM et al (2005) The risk of cesarean delivery with neuraxial analgesia given early versus late in labor. N Engl J Med 352:655– 665

Centre for Evidence Based Medicine, University of Oxford (2013) http://www.cebm.net/?o=1025. Retrieved 18 April 2014

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P et al (2011) The Oxford level of evidence 2. http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653. Retrieved 10 Jan 2014

American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia (2007) Practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia: an updated report by the American society of anesthesiologists task force on obstetric anesthesia. Anesthesiology 106:843– 863

Obstetric Anaesthesia Special Interest Group (2008) Obstetric anaesthesia: scientific evidence, 1st edn. http://dbh.wikispaces.com/file/view/Obstetric+Anaesthesia+Scientific+Evidence.pdf. Retrieved 24 April 2014

Sultan P, Murphy C, Halpern S, Carvalho B (2013) The effect of low concentrations versus high concentrations of local anesthetics for labour analgesia on obstetric and anesthetic outcomes: a meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth 80:840– 853

Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RM, Jones L (2011) Epidural versus non- epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:CD000331

Leighton BL, Halpern SH (2002) The effects of epidural analgesia on labor, maternal, and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 186:S69–S77

Wassen MM, Zuijlen J, Roumen FJ et al (2011) Early versus late epidural analgesia and risk of instrumental delivery in nulliparous women: a systematic review. BJOG 118:655– 661

Simmons SW, Taghizadeh N, Dennis AT, Hughes D, Cyna AM (2012) Combined spinal-epidural versus epidural analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10:CD003401

van der Vyver M, Halpern S, Joseph G (2002) Patient-controlled epidural analgesia versus continuous infusion for labour analgesia: a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 89:459– 465

Halpern SH, Carvalho B (2009) Patient-controlled epidural analgesia for labor. Anesth Analg 108:921– 928

George RB, Allen TK, Habib AS (2013) Intermittent epidural bolus compared with continuous epidural infusions for labor analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 116:133– 144

Halpern SH, Walsh V (2003) Epidural ropivacaine versus bupivacaine for labor: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 96:1473– 1479

Halpern SH, Breen TW, Campbell DC et al (2003) A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial comparing bupivacaine with ropivacaine for labor analgesia. Anesthesiology 98:1431– 1435

Douma MR, Verwey RA, Kam-Endtz CE, van der Linden PD, Stienstra R (2010) Obstetric analgesia: a comparison of patient-controlled meperidine, remifentanil, and fentanyl in labour. Br J Anaesth 104:209– 215

Ullman R, Smith LA, Burns E, Mori R, Dowswell T (2010) Parenteral opioids for maternal pain relief in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD007396

Klomp T, van Poppel M, Jones L et al (2012) Inhaled analgesia for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD009351

Dowswell T, Bedwell C, Lavender T, Neilson JP (2009) Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for pain relief in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD007214

Derry S, Straube S, Moore RA, Hancock H, Collins SL (2012) Intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection compared with blinded controls for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD009107

Smith CA, Collins CT, Crowther CA, Levett KM (2011) Acupuncture or acupressure for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7:CD009232

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Halpern, S.H., Garg, R. (2015). Evidence-Based Medicine and Labor Analgesia. In: Capogna, G. (eds) Epidural Labor Analgesia. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13890-9_21

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13890-9_21

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-13889-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-13890-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)