Abstract

Circular migration is nothing new as it has long been rooted in internal migration and cross-border migration flows in Asia. What is new is the current emphasis on managed circular migration as a triple win situation bringing benefits to all three parties involved—migrant workers, destination countries and origin countries. The objective of the Chapter is to assess the theoretical underpinnings of the issue of circular migration as reflected in Asian migration studies. The relative absence of theoretical studies on circular migration and mobility in the Asia-Pacific context can be partly explained by the poor quality of data on circular mobility, and the high incidence of irregular and informal movements across borders. Moreover much of the recent work in the region has been descriptive and empirical, focussing on exploitation of migrant workers, female domestic workers, trafficking issues and vulnerability, and the ‘migration and development nexus’. The Chapter reviews past studies in so far as they try to explain the theory behind the origins and processes of the circular migration phenomenon. Most early theoretical work on circular migration was produced in relation to internal population movements or rural urban migration. The paper next discusses existing theoretical analysis of two major Asian labour migration systems—Gulf labour migration and the Asia-Pacific migration movements—focussing on low skilled migration. This is followed by a discussion of more recent work on circulation of skilled workers or brain circulation and diaspora circulation. The general finding is that the recent literature fails to distinguish clearly between circular and temporary migration processes, and lacks an adequate theoretical foundation to explain circular mobility. The paper identifies gaps in the analysis, and proposes area for further research in the field of circular migration.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

3.1 Introduction

Circular migration is nothing new as it has long been rooted in internal migration and cross-border migration flows. What is new is the current emphasis on managed circular migration as a triple win bringing benefits to all three parties involved—migrant workers, destination countries and origin countries. Several comprehensive up-to-date reviews are available on broader issues of circular migration and its relevance particularly in the European context (McLoughlin and Münz 2011; EMN 2011; Wickramasekara 2011). In line with the theme of this volume, the objective of this chapter is to survey the theoretical discussions of temporary and circular migration in Asia.

First, the chapter reviews definitional issues and evidence on temporary and circular migration in Asia briefly. The next section reviews some past studies in so far as they try to explain the theoretical basis of such movements. In the final sections, the weaknesses and strengths of existing literature will be identified together with areas for further research.

3.2 Definitions and Notes on Methodology

3.2.1 Definitions and Evidence of Circular Migration

There are varying definitions of circular migration in the literature ranging from promotional definitions to generic ones (Wickramasekara 2011). The author maintains that a generic definition offers the best approach for understanding circular migration. “Simply defined, circular migration refers to temporary movements of a repetitive character, either formally or informally across borders, usually for work, involving the same migrants” (Wickramasekara 2011, p. 1). By definition, all circular migration is temporary. It is different from permanent migration for settlement and return migration involving one-trip migration and return.

To the extent that migration is defined in terms of permanency of move, the coverage omits “a great variety of movements, usually short term, repetitive or cyclical in character, but all having in common the lack of any declared intention of a permanent or longstanding change of residence” (Zelinsky 1971, pp. 225–226).

It is also necessary to distinguish between different types of circular migration:

-

Spontaneous (voluntary) circular migration and managed circular migration;

-

Circular migration of persons from developing countries and circular movement of persons from the diaspora to their home countries.

In discussing theoretical issues, spontaneous or voluntary circular migration offers more scope than managed ones. In the Asian context, there are no formal or managed circular migration programs except the seasonal worker programs of New Zealand (Recognised Seasonal Employer scheme) and Australia with the Pacific Islands. The Korean Employment Permit System (EPS) is not technically a circular migration scheme, but the introduction of the ‘Faithful Foreign Worker Program,’ whereby some workers can apply for a new permit subject to spending at least 3 months in their origin countries, makes it a managed circular migration (Castles and Ozkul 2013). The long-standing Gulf migration system is primarily a temporary migration program, which has elements of circularity to the extent that some workers may repeatedly go back for work there (Wickramasekara 2011).

On the one hand, all circular migration is in essence temporary migration because migrants have to eventually return to the home country in the absence of any right to permanency in the country of destination. On the other hand, all temporary migration forms do not lead to circular migration—most may involve a single migration cycle while some programs may lead to permanent settlement in destination countries like what transpired under previous guest worker programs in Europe. In this sense, circular migration is a subset of temporary migration.

3.2.2 Data and Measurement Issues and Evidence on Circular Migration

Given the inherent difficulties in measuring normal migration flows, it should be naturally more difficult to estimate circular migration. In national and international data systems on international migration, the term circular migration hardly appears. For instance, there is no single reference to either circular migration or circular migrant workers in the ILO manual on migration statistics (Bilsborrow et al. 1997) or the UN Recommendations on International Migration Statistics (United Nations 1998).

Hugo’s field work in Indonesian villages (Hugo 1982) highlighted that census and other statistical data collections bypass these movements. Lucas also confirms:

Yet circular migration is normally difficult to quantify, given the nature of census data; recording a person’s current location and place of birth reveals no migration, despite any intervening, circular movement. As a result, only specialized surveys really permit systematic analysis of circular migration. (Lucas 2003, p. 15)

Chapman and Prothero also argued as follows:

To comprehend its complex nature more fully, circulation must be investigated and analyzed at several scales: the micro (individual, family), the meso (community, settlement system, region) and the macro (country, continent, world). Consequently, the measurements and techniques to be employed are of critical importance and the data must be both longitudinal and cross-sectional. Far greater attention must be focused upon social, economic and political structures which bound and influence reciprocal flows and these must be examined from a range of assumptions. (Chapman and Prothero 1983–1984, p. 622)

The ILO manual and UN Recommendations recognize the categories of ‘seasonal workers’ and ‘temporary migrant workers.’ At the national level, one hardly finds any information on circular migration patterns involving overseas migration. Circular migrants are difficult to measure because they may not go through the registration systems in subsequent moves given their familiarity with the migration system. The lack of formal exit control measures in many countries also is another reason for missing information on such movements. Even recent surveys have omitted this category. For example, various reports of the periodic Kerala migration surveys which involve about 15,000 households in the State of Kerala have not made any reference to circular migration.

When migrants are part of a specific circular migration program based on an agreement between two countries, there is better scope for generation of movement data. This is true of the Employment Permit Scheme of the Republic of Korea.

The Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) provides separate information on a category of ‘rehires’ which could reflect repeat movements. The Philippines regulations distinguish between two categories of migrant workers returning to the same employer (“Balik-manggagawa”):

a) Worker-on-Leave—a worker who is on vacation or on leave from employment under a valid and existing employment contract and who is returning to the same employer, regardless of any change in jobsite, to finish the remaining unexpired portion of the contract.

b) Rehire—a worker who was rehired by the same employer after finishing his/her contract and who is returning to the same employer, regardless of a change in jobsite. (Department of Justice 2012, p. 3)

The first category is not strictly a form of circular migration because the movement is part of the initial migration episode. “Rehires,” as defined in the Philippines context, refers to a specific type of circular migration. The term ‘rehires’ underestimates the true extent of circular migration because it includes only those going back to the same employer. A circular migrant can join another employer in the same country or move to a different country for employment after the first migration experience because the basic criterion of circularity is that the same migrant is involved in repeated migrations, irrespective of the destination country. The share of rehires in total land-based outmigration in the Philippines has been in the range of 60–65 % of total migrant workers between 2008 to 2011 (POEA 2012). This could mean that total circular migration would be more than two-thirds of the total.

A study in Jordan found that only 10 % were first time migrants, while 46 % were there for the second time and the balance, 44 % more than twice. An ILO survey in the UAE and Kuwait however, revealed that only a quarter of those who moved were repeat migrants, but the sample was purposive and not representative of the general situation (Wickramasekara 2011).

A migrant re-integration survey carried out in Sri Lanka reported that only 40 % of migrant workers sampled had gone for foreign employment for a second time. Close to 20 % were third time migrants, and less than 10 % were fourth time migrants (SPARC 2013).

Contrary to popular view that permanent migration represents a one-way flow, Hugo has pointed out that permanent skilled migration movement from Asia to Australia is a two-way flow based on analysis of migration flows between 1993 and 2008 (Table 3.1).

In this sense, permanent migration streams also involve circular mobility elements.

3.2.3 Framework of the Study

A theory of circular migration has to address the following tasks:

-

a.

conceptualize the difference between circular migration and other forms of mobility, specially temporary migration;

-

b.

explain the factors that lead to the initiation of circular/temporary migration or circular mobility;

-

c.

highlight the reasons for continuation or perpetuation of circular migration;

-

d.

predict the impact and consequences of circular migration on parties involved: migrants themselves, host and origin societies.

This chapter recognizes the close links and parallels between internal and international migration (Standing 1984a; Skeldon 2006). As Skeldon remarked: “Internal and international migrations are integrated and it is necessary to consider them as a unified system rather than in isolation” (Skeldon 2006, p. 15). As shown in Sect. 3.3, early theories of circular migration in Asia were primarily based on analysis of internal migration.

3.3 Theoretical Research on Circular Migration in Asia

According to Massey et al. (1998b): “much of the literature on international migration is predominantly descriptive and theoretical, providing little opportunity for hypothesis testing or theoretical generalization” (p. 170). They cite several reasons for relative absence of theoretical studies on circular migration and mobility in the Asia-Pacific context (Massey et al. 1998c): relative recency of immigration in most countries, poor quality of data on international migration and high incidence of irregular and informal movements. While immigration in Asia may have been relatively new in the 1990s when they conducted the study, it is no longer the case.

Most work on Asian temporary migration across borders have been empirical since the large-scale movements that took place from the Gulf boom of the early 1970s. Concerns with feminization of migration and trafficking and smuggling of migrants became major preoccupations of international agencies which funded part of this research.

In the Asian context, rampant problems of abuse and exploitation of migrant workers, both in the Gulf and within Asian countries, have absorbed a lot of attention from researchers (Wickramasekara 2002, 2005). Asis et al. (2009) have shown that research funding by many agencies in Asia “seems to focus, almost exclusively, on particular issues such as trafficking, to the exclusion of other concerns” (Asis et al. 2009, p. 82).

More recently the issue of migration and development also has featured high on the research agendas (Asis et al. 2009). As Asis et al. (2009) point out: “In general, migration research has been preoccupied with capturing bits and pieces of the phenomenon as it unfolds, a task that has limited most research to descriptive analyses” (p. 98).

3.3.1 Early Theories of Circular Migration Processes Involving Internal Migration

Since the 1960s, there has been rich literature on circular migration and mobility concerned with internal population movements (Bedford 1973a, b; Hugo 1975, 1982, 1984; Goldstein 1978; Standing 1984b).

3.3.1.1 Bedford’s Pioneering Analysis of the Transition in Circular Mobility, New Hebrides (Bedford 1973a, b)

Bedford carried out a survey on the movements of people of New Hebrides from 1800 to 1970, in arriving at his views on circular mobility. In his view, circulation was more common than migration in traditional tribal and peasant societies (Bedford 1973a, b). He distinguished between oscillation, which involves routine movements of less than 1 month, and circulation. He explains the rationale of circular migration as follows:

Plural societies and dual economies exist in various forms in most colonial or formerly colonial countries, offering a contrast in ways of life that can be particularly stark. A compromise often adopted by members of the indigenous population is circular migration. Wishing to retain the security of their traditional institutions, generally associated with residence in rural communities, while obtaining some of the benefits of involvement in non-indigenous economic activities, they circulate between village or hamlet and the centres of wage employment-plantations, mining settlements, towns. (Bedford 1973b, p. 189)

It is also important to note that the mobility of New Hebrides people went beyond national borders to other islands as well as to Queensland, Australia. The main motivation was the demand for non-indigenous material goods. Later migration to cash cropping areas and movement to towns within the New Hebrides became common. Bedford adds:

This brief survey of the evidence of over 150 years does not reveal a transition leading yet to permanent redistribution: it does however, reveal a transitional sequence within a particular class of movement behaviour-circulation. Throughout the post-contact period, a basic and traditional pattern of inter-island mobility has persisted in which permanent change in place of residence is exceptional. (Bedford 1973b, p. 207)

This is because for most islanders, the rural communities remain as their permanent homes, “as bases from which to participate in a variety of economic activities: subsistence gardening, cash cropping, local business ventures and wage employment” (Bedford 1973b, p. 226).

3.3.1.2 Hugo’s Analysis of Circular Migration in Indonesia and West Java

Hugo’s analysis of Indonesia is the most comprehensive assessment of circulation undertaken in Southeast Asia. “The work of Graeme Hugo (1975) on population mobility in West Java constitutes a milestone in research on the topic, both because of its innovative character for the region and because of the many insights it provides on the role of circulation and commuting in total population movement” (Goldstein 1978, p. 39).

Hugo has summarized these arguments in two research articles (Hugo 1982, 1984).

Circular migrants usually maintain some village based employment, and the frequency, with which they migrate is determined by the distance involved and the costs of traversing it, their earnings at the destination, and the availability of work in the home village. (Hugo 1982, p. 61)

What is interesting are the discussions of what explains circular or non-permanent migration. Hugo considers three theories: (a) sociocultural explanations; (b) economic explanations; and, (c) uneven development or uneven impact of capitalism.

The first view argues that circular migration has become institutionalized within certain ethnic groups in Java, but Hugo saw that there were a number of complex sets of interacting forces, among which economic considerations are also important. As regards economic explanations, he advances the hypothesis of maximizing family income and utility from consumption.

[M]ost of the non-permanent migrant households could not earn sufficient incomes in either the city or the village to support themselves and their dependents. Thus, circular migration or commuting provides a means for families to maximize their incomes by encouraging some members of the household to work in the village at times of peak labor demand and to seek work in the city or elsewhere at slower times while other members of the household remain to cope with limited village-based labor demands. …. Thus, by earning in the city but spending in the village, the migrant maximizes the utility gained from consumption. (Hugo 1982, p. 70)

The other plausible reason is risk aversion or minimization since a “circulation strategy keeps the mover’s options in the village completely open so that the risk of not being able to earn subsistence is reduced by spreading it between village and city income opportunities” (Hugo 1982, p. 70). Village-based support systems can be mobilized in times of economic or emotional need, and lack of resources does not allow them to take the risks involved in permanent migration to the city.

The third explanation argues that mobility resulting from the uneven impact of capitalism generates substantial inequalities across sectors, classes, and space. Hugo cites Frobes who stated that this type of circular migration delays the formation of a proletariat, preventing the emergence of “two social groups: an urban-based non-landowning proletariat and a small farming class.” Instead the outcome is an “undifferentiated group involving themselves in both the capitalist and peasant modes of production.”

Hugo (1982) argues that all three explanations are complementary. The first two economic explanations represent a micro-level situation whereas the third theory—uneven development—implies that macro-structural forces in society are important to explain the migration phenomenon.

Hugo also analyzed the impact and consequences of the moves which have a close parallel in current research on migration and development. For instance, he highlighted the role of remittances—again a major benefit of the triple win argument currently being advanced (Wickramasekara 2011). The study found that 60 % of the income of commuter households were derived from remittances, while remittances from circular migrants amounted to almost half of their households’ total income.

Hugo also posed the question on whether the observed high level of non-permanent mobility was simply a transitional phase followed by permanent relocation of many migrants to urban areas. While he rightly pointed out the need for integrating the known causes of this circular mobility into a coherent theoretical framework, the study did not attempt to do it.

3.3.1.3 Circular Migration in Southeast Asia: Some Theoretical Explanations (Fan and Stretton 1984)

The above study also deals with the issue of rural-urban labor migration. It offers two models to provide theoretical explanations of circular migration.

First, it is the decision of the family to maximize income as well as utility from consumption referring to spatial allocation of family resources. Second, is the hypotheses of income maximization-cum-risk aversion options for the family The study advanced the hypothesis that “a risk-averse decision-maker prefers circular migration to permanent migration even if the latter promises higher expected income” (Fan and Stretton 1984, p. 339).

Hugo (1982) had also used these two models to explain circular migration from villages of Indonesia as shown above. As he highlighted, the models are complementary rather than competitive.

The analysis draws upon village studies reviewed by Goldstein (1978) and urban occupation studies done by different researchers in Southeast Asia. It is based on migrants in the urban informal sector in Bangkok, Jakarta and Manila who have adopted a circular migration pattern. The strong network of contacts is an integral part of the circular migration process because it is through these contacts that a potential migrant can secure a job in the urban sector. It was observed that circular migrants from the same rural area and same job tended to live together in the city, which ensured social support and lower living costs. Thus, the family would distribute its labor resources between the village and the urban center to maximize family earnings, usually by sending the main income earner to the city while the rest of the family remains in the village. Fan and Stretton (1984) argue that a sufficient set of conditions must be present for a circular migration pattern to emerge. Among the conditions are: “the rate of return in the urban sector is relatively higher than in the village (at least for a large part of the year) and either living costs are higher in the city than the village … or the family has a rural-biased consumption preference, or a combination of both” (Fan and Stretton 1984, p. 346).

The second model of risk aversion indeed complements the income-utility maximization model by showing that if one aims at maximizing income and is risk-averse, then circular migration would be preferable than other options.

Risk aversion provides an additional reason for keeping a home base in the village. If plans fail to materialize, the family can always fall back on its existing mode of livelihood. By keeping his contacts, the circular migrant goes to the city only when work is available, thus eliminating to a great extent the uncertainties of job-hunting.

Fan and Stretton (1984) therefore, conclude that circular migration is a rational choice of risk-averters, and that remittances and the repetition of the circular pattern act as important mechanisms to strengthen the linkages between the rural and urban sectors.

3.3.2 Asian Migration Systems

The Asian labor migration system is largely a temporary labor migration system which has seen several waves of migration. The initial trigger was the Gulf oil boom of the early 1970s which enabled the Gulf countries to embark on ambitious modernization programs calling for massive labor inflows, particularly from Asia. The rapid development of Malaysia and Thailand also led to large inflows of labor from neighboring countries, initially on irregular basis. Apart from Hong Kong SAR, other East Asian countries had no formal labor admission schemes for low- skilled workers despite the demonstrated demand (Wickramasekara 2002). The Taiwan Province of China in the early 1990s and the Republic of Korea more than a decade later (in 2004) liberalized the admission of low-skilled workers while Japan has still not relaxed its policy of denial. At the same time, Asian skilled workers, particularly from China and India, have migrated to major European countries, and to Australia and New Zealand within the region, mostly on a permanent basis. More recently, New Zealand, followed by Australia on a smaller scale, launched schemes for the admission of workers from Pacific countries on a seasonal basis for work mainly in agriculture. The Recognised Employer Scheme of New Zealand is a good example. Current types of migration flows include the following.

-

a.

Migration to the Middle East and the Gulf region: mainly from South Asia although the Philippines and Indonesia also account for part of the flows to these destinations.

-

b.

Intra-Asian flows: mostly to Malaysia, Hong Kong SAR and the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Thailand and Taiwan (China).

-

These flows are dominated by migrants from Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Philippines, and Thailand) and China and Mongolia to some extent. There is a substantial volume of irregular cross border migration flows. South Asian countries also send workers to Malaysia and Singapore and to the Republic of Korea under its Employment Permit System (EPS).

-

Within South Asia, there are cross border flows from Afghanistan to Pakistan, Bangladesh to India and Pakistan (largely undocumented) and from Nepal to India (within a free movement regime).

-

c.

Documented flows to developed country destinations within Asia and outside Asia, mostly of skilled persons. Australia and New Zealand are the major destinations in the Asia and Pacific region, while destinations outside Asia include Canada, the United States, the UK, and other European countries. The flows consist of both permanent settlers and temporary workers, and the youth may account for a substantial share.

-

d.

Irregular flows to developed Asian destinations, Australia and New Zealand and to Western countries from South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia (China and Mongolia).

-

e.

Seasonal workers from the Pacific island countries and other Asian countries brought to New Zealand under the Recognised Seasonal Employer Scheme (RSE) are bound by strict regulations on duration of stay. This is the closest to circular migration as defined above.

-

f.

Working Holiday Maker scheme: a few Asian countries (Japan, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, and Thailand) are entitled to send workers to Australia under this program but not the bulk of poorer Asian countries. This is a temporary scheme which does not formally provide for repeat migration.

Most of these flows are not circular migration per se, but there are elements of circularity in the temporary migration schemes. For instance, the Gulf migration forms part of circular migration when the same people undertake repeat migration. In a broader and loose sense, the system can be described as circular migration because previous groups of temporary migrants are being replaced by subsequent waves of temporary migrants and only some may be new migrants. In other words, there is migrant circulation though it may not involve the same migrants. But in this Chapter, I shall use the narrow definition of circular migration, i.e., repeat movements by the same workers.

The only attempt at an extended discussion of the theory underlying Asian migration is the monograph by Massey et al. (1998c). The monograph discussed Asian migration in terms of two systems: the Gulf migration system (Massey et al. 1998a) and the Asia-Pacific system (Massey et al. 1998b). These are discussed in the next section.

3.3.2.1 The Gulf Migration System

Migration of workers to the Gulf countries was a major development that sustained temporary labor migration regimes following the virtual termination of European guest worker programs. The oil bonanza of the early 1970s enabled Gulf countries to modernize their economies resulting in large demands mainly for low-skilled workers. Over time, most of the expatriate work force have been drawn from Southeast and South Asia. It is a classic temporary labor migration system based on fixed-term contracts valid mostly from 1 to 3 years. It is also a strictly rotational system with some circular migration occurring when migrant workers re-migrate with new contracts. Competition has driven down wages, and working conditions are proverbially poor. Intermediaries play a major role at both ends which further erodes the benefits of labor migration for workers and source countries. Abuse and exploitation of migrant workers and denial of their basic human and labor rights are very common, with private sector employers acting with virtual impunity (Wickramasekara 2005; Verité 2005). Standing’s (1984a) characterization of international circular migrants applies equally well to the Gulf situation:

Being vulnerable as aliens and ignorant of their rights as citizens, if they have had any, they have represented a highly exploitable labor supply, workers who could be used to depress wages (through a resignation to accept lower wages and through exerting pressure on average wage rates); they have facilitated an increase in the detailed and social division of labor and helped perpetuate and accentuate a stratified labor force in very much the same ways as with internal labor circulation. (Standing 1984a, p. 34)

While this temporary labor migration system with elements of circularity has continued for about four decades, it cannot by any means serve as a model to be replicated in liberal democratic societies.

There have been few attempts to discuss the Gulf system in terms of circular migration. There is hardly any information on the extent of circular migration in the Gulf system except, to some extent, for the Philippines.

The neoclassical argument of persons migrating for higher wages still applies given existing wage differentials between origin and destination countries. Yet, the difference has been narrowing over the years, especially for low-skilled workers. There is also wage discrimination by nationality (Wickramasekara 2011).

Massey et al. (1998a) maintain that two theoretical models are more relevant than other theories in understanding levels and trends in Gulf migration: segmented labor market theory and social capital theory.

As regards segmented labor market theory, Gulf migration has been demand driven from the beginning. There is clear segmentation of the labor market between a highly pampered public sector, mostly reserved for native workers, co-existing with another sector consisting of small and medium enterprises largely reliant on cheap immigrant labor. Unlike in Piore’s (1979) theory, this segmentation is not because of rapid industrial transformation in Gulf countries, but because of the vast infrastructure and other investments made possible by the oil bonanza. The immigrant sector makes up a large share of the economy, with migrant workers accounting for 60–90 % of the total workforce in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) States. Over the years, there has been the Asianization of the workforce “whose migrants can be more effectively exploited through policies of deliberate discrimination” (Massey et al. 1998a, p. 159) unlike Arab workers.

Massey et al. (1998a) also emphasize the role of social capital—institutions and networks—in explaining the perpetuation of Gulf migration even in the presence of “rather draconian labor market and immigration policies” (p. 159). Undoubtedly the Gulf region presents a quite difficult environment with no pathways to permanent settlement and lack of family unification provisions for the low skilled who comprise the bulk of the migrants. Settled communities of migrants had emerged initially, especially among migrants from the Arab countries. The Gulf War and its aftermath served as a convenient trigger to engage in mass deportation of established communities of Jordanians, Palestinians, and Yemenis except Egyptians with the marked shift to Asian workers. There has been growing social networks over time among Indian and Pakistani workers in the Gulf region who can provide useful information and contacts for their friends and relatives to migrate to the region.

At the same time, a major recruitment industry has been built up in both origin and destination countries which promote and perpetuate migration. These consist of large networks of recruitment agencies especially in origin counties, subagents, the sponsors of migrants or kafalas in destination countries, government bureaucracies, travel agents and other service companies, and former migrants themselves acting as agents. They have a vested interest in promoting continuous migration given the large rentier incomes involved.

Massey et al. (1998a) did not find any evidence, however, that the forces outlined by the world systems theory were relevant to the initiation or perpetuation of international migration to the oil-rich nations of the Gulf (Table 3.2).

3.3.2.2 Asia and Pacific System

Massey et al. (1998b) reviewed the Asia and Pacific system, treating it as a separate migration system from the Gulf one. Their analysis probably reflects the mid-1990s situation when the intra-Asian system had not matured fully, and Thailand had not become a major destination.

They conclude that the neoclassical economics proposition that migration flows are driven by wage differentials between origin and destination countries is supported by empirical evidence.

Whereas neoclassical economics predicts a one-time move to a region of higher wages, the new economics posits successive periods of temporary foreign labor to achieve specific goals such as risk minimization or capital accumulation. Circularity, of course, reinforces social obligations embedded in Asian kinship structures and ensures continued family control over migrant behaviour, and more significantly, over migrant income. (Massey et al. 1998b, p. 177)

Segmented labor market theory advanced by Piore (1979) may apply better to some Asian destinations, such as Taiwan (China), the Republic of Korea, Hong Kong SAR and Singapore, since these countries had achieved structural transformation of the economies. According to Massey et al. (1998b) the segmentation mostly occurred along the lines predicted by Piore (1979) “with a bifurcation of employment into primary and secondary sectors” (Massey et al. 1998b, p. 182). The jobs which do not appeal to native workers are mostly in agriculture, construction, domestic service and small and medium enterprises.

Massey et al. (1998b) also favor social capital theory in that migrant networks explain ‘perpetuation of international migration.’ According to them, “the existence of a stock of migrants in a potential destination is the most important predictor of whether a particular community will send migrants to that area in the future” (Massey et al. 1998b, p. 186). However, they noted the absence of studies to formally support this hypothesis either for migration to the Gulf or within Asia.

3.4 More Recent Research: Illustrative Cases

There has been a large gap in the literature on circular migration between the 1980s and the late 2000s when the renewed interest in circular migration came up in the context of migration and development. The Global Commission on International Migration highlighted the potential of circular migration which was later picked up by the European Commission, Global Forum on International Migration and Development, and the International Organization for Migration, among others.

This section reviews a few studies dealing with the theoretical aspects of circular migration in the context of some Asian countries.

3.4.1 Circular Migration Patterns to Japan

In the case of Japan, two types of circular migration can be observed. One is the admission of entertainers who get 3- to 6-month visas. The other group consists of migrants of Japanese descent described as Nikkei. There are only a few studies which attempt to explain the rationale of these pattern of mobility.

3.4.1.1 Transnationalism Among Japanese Brazilian Migrants

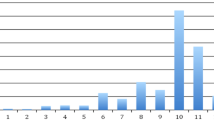

The revised Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Law in 1990 provided for immigrants of Japanese descent to migrate for employment in Japan with renewable working visas and a basis to conduct ‘any activities’ in Japan. The greatest number came from Brazil. They have been incorporated into the labor market in Japan as low-skilled but documented foreign workers. One distinguishing characteristic of this migration is the prevalence of back and forth movements, particularly between Brazil and Japan (Takenoshita 2007). Table 3.3 shows that two-thirds of those sampled had moved more than once to Japan, and almost one-quarter had moved three times.

The objective of Takanoshita’s study was to establish whether back-and-forth movement between the origin and destination countries can enhance socioeconomic positions of Nikkei migrants. The findings did not support the hypothesis of transnationalism that circular migration helped Brazilian migrants in Japan to upgrade their socioeconomic status and to adapt well into Japanese society. These migrants could not engage in transnational practices to improve their situation given the adverse impacts of the labor market structures and lack of support for integration in the host country. This finding is similar to that of the study of entertainers below.

The author explains this outcome in terms of the dual labor market hypothesis or segmented labor market theory as advanced by Piore (1979). Brazilian migrants were mostly employed in the secondary labor markets and informal activities characterized by poor wages and working conditions and lack of employment security.

A recent analysis by Sasaki (2013) confirms the fragility of the labor market status of Brazilian migrants who are treated as flexible and disposable workers in the aftermath of the crisis.

The economic crisis in late 2008, however, resulted in a drastic change in the existing pattern of migration. In response to massive joblessness in the Japanese manufacturing industry, hundreds of thousands of Brazilians repatriated to Brazil, leading to a widespread breakdown of the transnational system of migration. (Sasaki 2013, p. 1)

Their vulnerability arose from their high concentration in the manufacturing industry in Japan and their dependence on the temporary work agencies which meant they could not compete with native workers in the job market. The lack of any integration support on the part of Japanese authorities contributed to the outcome.

These studies of Nikkei workers support the segmented labor market hypothesis.

3.4.1.2 Japan and Entertainers

The study of Filipino entertainers by Parreñas (2010) takes up the issue that their experience of settlement does not always fit the dominant perspective of transnational migration. She argues that circular migrants hold ‘feelings of greater affinity for the home society.’ Her field study highlighted limited integration in the host society, with few prospects for settlement as they are generally segregated in time and space. The short period of migration means that Filipina entertainers have to plan for their departure immediately on arrival. The study questions the assumption in the literature that circular migrants will eventually become permanent residents. She calls for ‘the formulation of new theoretical frameworks that better capture the qualitatively distinct experiences of circular migrants’ (Parreñas 2010, p. 301).

As Parreñas (2010) observes: “In this highly competitive industry, it is rare for entertainers to complete more than two or three labor contracts before they permanently retire in the Philippines, because not only does the supply of entertainers far exceed the demand, but the greater preference for younger women also reduces the likelihood of return migration. In this industry, youth is more valuable than experience” (p. 321).

She distinguishes between circular migration from ‘transnational migration’ which she believes to be based on the experiences of permanent migrants. Yet, transnational migration could simply mean cross-border migration irrespective of the duration of stay. While transnational communities coincide to a large extent with the settled diaspora communities, ‘transnational’ would not necessarily mean long-term migrants. In her view, “Short-term migrants tend to be target earners. In the case of Filipina entertainers, they ‘earn money in Japan and spend it in the Philippines.’ They hold feelings of greater loyalty for the Philippines” (Parreñas 2010, p. 303). It would be difficult to establish the last point based on the evidence of the study. Being on short visas and the exclusionary measures and ‘the barriers that impede their feelings of membership in the host society’ (p. 306) as stressed by the author, they of course, have no option but to return to the Philippines.

She rightly recognizes the combination of factors that determine the likelihood of long-term (transnational) and circular migration: migrant agency, state policies (whether liberal or authoritarian), geographical proximity, skill profile (whether high skilled or low skilled) of the migrant, and flexible visa regimes which allow the migrant to return freely to the host country. Low skilled migrants are more likely to be circular and temporary migrants as the Asian and Gulf experience has shown who are subject to various exclusionary practices: “Poor wages, ineligibility for family reunification, restricted durations of migration, and limited political rights” (p. 307).

Her conclusion that “ … accounting for short-term migration requires a paradigmatic shift from our models of settlement based on long-term migration” (Parreñas 2010, p. 320) is hardly new. She suggests that a “more suitable analytic framework for documenting the settlement of temporary migrants would be to look not at the extent of their integration but instead at their segregation in the host society” (p. 307) on which considerable work has been done in the context of Gulf migration.

3.4.2 Circular Mobility in China

China’s internal migration presents a classic example of circular migration where millions migrate to the cities every year and return to their homes before undertaking repeat migration. This type of circulation has now been going on for almost three decades. The rapid growth of coastal cities and the demand for low skilled workers, and widening rural- urban income disparities led to the large movements involving more than 125 million workers. Most migrants maintain close links with home areas, which act as a safety net, especially because migrants retain access to land and housing in their places of origin.

It is important to note that China, in common with socialist economies, has imposed many restrictions on rural to urban migration, including the household registration or hukou system of China which guarantees access to urban entitlements. While these have been relaxed in varying degrees in recent years, many barriers still remain. Moreover, rural movers also face serious rights violations especially in the workplace, and experience discrimination in cities although they are citizens of the same country.

The literature survey (of material in English) did not highlight much theoretical explanations of this phenomenon unlike in the case of Indonesia. Fan (2011) argues that circular migration and split households have become long-term practices among rural Chinese, although conventional assumption has been that these are temporary phenomena. Based on a survey of migrants conducted in 2008, her research showed that the majority of rural migrants had no intention to settle down in cities.

Fan (2011) almost echoes the findings of Hugo’s for Indonesia.

By straddling the city and the countryside, migrants can earn urban wages as long as they have jobs, support the rest of the family at a rural and lower cost of living, and return to the home village or rural town if migrant jobs dwindle. In this light, circulation, rather than permanent migration, allows the migrants to obtain the best of both worlds. To them, therefore, settling down in the city is not inevitable and may not be the best choice. (Fan 2011, pp. 13–14)

According to the study, the main factors which promote repeat migration are the state migration control system, lack of access to the household registration system, which denies many benefits including health benefits for the family, and schooling for children, and access to family support in the home areas.

Hu et al. (2011) find that more educated and more experienced migrants tend to be permanent urban residents, while those with more children and land at home are likely to be circular migrants. Although rural people have been allowed to move freely between cities and their homes, most of them are still denied permanent urban residency rights and associated social benefits defined by the hukou system.

Our results show that compared with their circular counterparts, permanent migrants tend to stay within the home provinces and are more likely to have stable jobs and earn high incomes and thus are more adapted to urban lives. We also find that more educated and more experienced migrants tend to be permanent urban residents, while the relationship of age and the probability of permanent migration is inverse U-shaped. Due to the restrictions of the current hukou system and the lack of rural land rental market, those people with more children and more land at home are more likely to migrate circularly rather than permanently. (Hu et al. 2011, p. 64)

Access to hukou of large cities is still tightly controlled, with less than 20 % of those with formal urban hukou having got them at the prefecture-level or provincial capital cities. Rural migrants cannot bring their children to cities and afford them education due to hukou restrictions. The lack of a rural land rental market also has a negative impact on migrants’ decision to stay in cities permanently.

3.4.3 Afghanistan: Transnational Ties and Circular Migration Patterns

Contrary to popular impressions of movements motivated by seeking asylum and refugee status, there is increasing evidence that the bulk of recent movements of Afghan persons are for temporary, seasonal, and circular migration. Research also highlights that circular migration, in the sense of repetitive migrations of a short or temporary nature, are common. Most of this earlier research did not use the term “circular migration,” but instead used terms such as “back and forth movements” or “transnational mobility,” which seem to capture the essence of the process (Monsutti 2006). There is general consensus that migration and the formation of transnational networks are key livelihood strategies for the people of Afghanistan.

Monsutti (2006, 2008) highlights the complexity of motivations behind migration and argues that it is too simple to describe it as an outflow of refugees. In his view, neither the definition of "refugee" in official international texts nor the various typologies of migration offer an adequate analytical framework to understand the migratory strategies of the Afghan population. While most movements took place due to the direct effect of war, their movements have occurred within the context of a longstanding tradition of migration and the pre-existence of transnational connections. Monsutti explains as follows:

Afghans have continued to make constant journeys back and forth as part of what is a dynamic process that leads to complex social adjustments. It is a cultural model, not a simple act of flight followed by integration or assimilation in the host country, or return to the country of origin. In fact, repatriation in the Afghan context does not imply the end of migratory movements, especially in more recent years. The probability of further departures, at least of some household members, is high due to the use of migration as a strategy to secure livelihoods. Factors which induce asylum-seeking are not necessarily the same as those which perpetuate migration and discourage return to Afghanistan. Migrants have woven networks of contacts that make it easier to move between different countries. Addressing the original causes of flight does not constitute a guarantee to bring current migratory movements to an end, as the factors sustaining transnational movements of Afghans have come to form more or less stable systems. (Monsutti 2006, p. 1)

This forms the basis of circular migration movements in Afghanistan whether as voluntary returnees or as deportees because repatriation in the Afghan context does not imply the end of migratory movements, especially in more recent years. The returnees are mostly from Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran, where there is increasing pressure by the authorities to send Afghan migrant workers back. As Monsutti (2006) rightly pointed out “The probability of further departures, at least of some household members, is high due to the use of migration as a strategy to secure livelihoods” (p. 1). Yet, the fact remains that most of these movements are informal and irregular in nature, although those migrating may not consider them as such.

3.4.4 Thai Repeat Migrants and Remittances

The study by Lee et al. (2011) is not about the initiation or perpetuation of circular migration. The question posed was “whether repeat migrants are different from first time migrants in terms of their remittances behaviour” (Lee et al. 2011, p. 144). Stark (1978) suggested that an individual remittance is initially low, but increases with time as migrants adjust to their new environment, settle in their new destinations and are relieved of the initial costs associated with moving. However, he also stated that individual remittances will decline as altruism wanes over time. This is because migrants’ commitment and attachment to their families and home areas may weaken over time. It may apply to those permanently migrating

The authors hypothesized that repeat migrants are also less likely to remit to their home country, compared with the first-time migrants. They have based their analysis on a survey of Thai workers abroad, conducted by the Asian Research Centre for Migration (ARCM). Of the 379 workers in the selected sample, 64 % were first-time migrants, 27 % were second-time migrants and only nine percent had migrated three times or more. Some 22 % also had stated that they would migrate again.

The authors conclude: “Repeat migrants are less likely to send remittances, but are more likely to save, compared with first-time migrants. This finding suggests that first-time migrant workers remit most of their earned income to Thailand, while those who repeat migration prefer to keep their money and are less likely to remit it” (Hu et al. 2011, p. 149). They explain this behavior in terms of initial debts incurred in the process of migration which have to be paid off immediately. The results also support the ‘remittance decay hypothesis’ of New Economics of Labor Migration (NELM).

3.5 Skilled Migration, Brain Circulation and Diaspora Circulation

Issues of brain drain have been a concern since the 1960s with the high outflow of skilled workers from developing countries to developed destinations. It was mostly seen as a one-way flow leading to permanent settlement in countries of destination. Later, this view has given way to more optimistic approaches, such as brain circulation and brain gain, recognizing the role of return migration, remittances, transnational practices, and diaspora knowledge networks and skills transfers, among others (Biao 2005; Wickramasekara 2003). Yet, there has been a lag in development of theoretical perspectives on skilled migration. For instance, Iredale has pointed out.

In the current situation, highly skilled migration represents an increasingly large component of global migration streams. The current state of theory in relation to highly skilled migration is far from adequate in terms of explaining what is occurring at the high skill end of the migration spectrum. (Iredale 2001, p. 7)

Biao (2005) also remarked: “The transnational approach was more a result of the recognition by government and international agencies of the new economic and technology reality than led by theories” (p. 2).

There is considerable interest in the role of the diaspora and its circulation mainly due to the recent emphasis on the migration and development nexus. In view of the overriding importance of China and India in benefitting from diaspora linkages, Asia has emerged as an important locus for deliberations on the migration–development nexus with a number of actors playing a key role. Asis et al. (2009, p. 92)conclude that “there is, on the whole, a theoretical lag between migration and development literatures globally, including in Asia”.

3.5.1 Global Dynamics and Migration of Highly Skilled Asian Workers

In an analysis in the early nineties, Ong et al. (1992) attempted to explain the migration of the highly educated Asians in terms of global dynamics. They distinguished between unskilled labor, skilled manual labor and the highly educated. They argue that unlike unskilled and skilled manual workers, highly educated workers are highly dependent on advanced economies to practice their trade. Unskilled labor is not tied to any particular nation because technology is embedded in the machinery that workers use. Skilled manual labor operates with a technology that is already fully dispersed to the developing countries, eliminating any special linkage to advanced countries. Usually the nature of on-the-job training bestows upon these workers the benefits of being in a sheltered segment of the labor market, thus providing an incentive to remain.

Globalization and global inequality generate the economic incentives for the highly educated to migrate for better living standards abroad. They argue that the migration of highly-educated Asians have some unique features compared to general migratory movements for three reasons: first, most of the training received is in industrial nations; second, unequal development on a global scale contributes to mobility; and, third, the reverse flow of returning students or visiting scholars to developing countries benefits home countries. Ong et al. add:

While the global articulation of higher education and the formation of an international class of labor are preconditions in the movement of the highly educated, it is global inequality that generates the economic incentives for individuals to leave a less developed country for a developed country. Differences in the standard of living between developed and developing countries are in some ultimate sense the underlying cause of migration, when it is not motivated by flight from repression or political disorder. (Ong et al. 1992, p. 556)

They identify a major difference between earlier labor migration and the post-1965 migration of professionals in terms of circulation and return of professionals. Unlike earlier departures, many of them return to their native countries for a period of time and engage in knowledge transfer before again returning to their host countries. The authors also highlight the circulation of the highly skilled between origin and host countries although on a small scale playing a crucial role in the transfer of technology.

Their argument that highly educated labor from Asia is only fully empowered for production in advanced economies is no longer true because a number of Asian countries have also transformed into advanced economies.

3.5.2 Migration of Knowledge Workers

One of the first analysis of the transnational approach and positive aspects of skilled migration in Asia (with focus on India) was conducted by Khadria (1999). He reviewed the issue from the broader notion of human capital and the impact of the growth of a diaspora. Based on the analysis regarding knowledge workers from India to the USA over three decades, he concludes that the first generation effects of remittances and skills and technology transfer through returns have been limited. He therefore, focuses on the ‘second-generation effects’ of brain drain which have the potential for broad-based impacts through contributions of the diaspora to education and the health sector and increase the productiveness of the people—the human resource base in India. His pioneering analysis provided a framework which has been used widely in discussing diaspora contributions, particularly in the case of India.

An interesting feature is his argument that physical return is not important since skilled persons can make these contributions while abroad. The policy implication is that governments and international agencies should not focus so much on return home since the conditions that led to their initial emigration have not changed. Therefore, attention should be on measures to maximize the benefits which could flow to origin countries from engaging positively with knowledge worker emigration. This will come from ‘second generation’ effects flowing from the assets generated by knowledge workers who stay abroad and who have gained the maximum possible returns from their involvement in a foreign labor market.

While Khadria’s analytical framework about transnational linkages and mechanisms has not been well-developed, the idea of circulation of skills and the contributions while abroad have influenced further analysis on the issue.

3.5.3 Iredale’s Analysis of Migration of Professionals

Iredale (2001) reviewed theories and typologies of migration of professionals citing examples from Asia. According to her, increasing globalization of firms and internationalization of education are major forces which have promoted the migration of professionals. Although the paper did not deal specifically with circular mobility, she noted an increasing tendency for temporary mobility of professionals creating a category of ‘skilled transients.’ While existing theory is inadequate in explaining high skilled migration, she highlights that it is important to focus on transnationalization or internationalization of professional labor markets in fields such as information technology and nursing.

She categorizes skilled migration in terms of six typologies according to motivation, nature of source and destination, channel or mechanism, length of stay (permanent, circulatory/temporary, mode of incorporation in host country labor markets, and national/international profession or the nature of the profession). She argues that the last factor is very important in explaining skilled migration flows.

While Iredale (2001) has drawn attention to the tendency of governments to admit skilled workers on temporary schemes on the grounds that labor shortages are immediate and short-term in nature. But her analysis does not deal with mobility patterns of such workers as circular migrants or otherwise.

3.5.4 Circulation of Transnational Entrepreneurs

Saxenian’s (2000) research has emphasized the importance of circulation of highly skilled entrepreneurs, particularly from Asian countries.

The emergence of parallel Silicon valleys in cities, such as Bangalore, Bombay, Beijing, Shanghai, and Taipei, has been primarily facilitated by expatriate scientists in the US Silicon Valley.

As the “brain drain” increasingly gives way to a process of “brain circulation,” networks of scientists and engineers are transferring technology, skill, and know-how between distant regional economies faster and more flexibly than most corporations. (Saxenian 2002, p. 183)

Instead of draining their native economies of human skills and resources, these “circulating” immigrants have brought back valuable experience and knowhow to local economies. It is different from brain exchange in that the same skilled persons are commuting back and forth between source and destination countries. A survey of Silicon Valley emigrant professionals found that 80–90 % of Chinese and Indians having business relations in their home countries travel more than five times a year to their countries (Saxenian 2000).

Saxenian (2011) described transnational entrepreneurs as the ‘new Argonauts’.

This globalisation of entrepreneurial networks reflects dramatic changes in global labor markets. Falling transport and communication costs allow high-skilled workers to work in several countries at once, while digital technologies make it possible to exchange vast amounts of information across long distances cheaply and instantly. International migration, traditionally a one-way process, has become a reversible choice, particularly for those with scarce technical skills, while people can now collaborate in real time, even on complex tasks, with counterparts far away. (Saxenian 2011, p. 2)

Saxenian’s analysis has contributed to better conceptualization of circular mobility of high tech entrepreneurs between the USA and Asia.

3.5.5 Australian Permanent Migration and Circular Movements

Hugo has analyzed circular mobility patterns in Asian high skilled migration to Australia based on migration flows over more than a decade. In his view, “Circularity, reciprocity and complexity are structured features of Asian migration to Australia, not a peripheral or ephemeral feature” (Hugo 2009b, p. 30). In an analysis of migration flows between Australia and China and India, “the migration relationship is best depicted as a complex migration system involving flows in directions and circularity, reciprocity, and remigration.”

Hugo developed a conceptual scheme to identify the main components of the migration system, and showed that many migrants transited between the different elements in the system. The inference is that the traditional conceptualization of the migration relationship between India and China, on the one hand, and high income countries, on the other hand, as being ‘South-North’ in nature was hardly appropriate. He discussed the implications of reconceptualizing mobility in this manner for understanding the migration process and for the development of migration policy in China, India and Australia (Hugo 2008). He defines circular migration in the context of Australian movements as follows: “This involves long-term but temporary migration of Asians to Australia and Australians to Asia. The main groups are students and long-term temporary business migrants. These are people who will spend more than a year at the destination but always with the intention to return. They take out temporary residency at the destination” (Hugo 2008, p. 269).

He highlights “a new type of ‘hyperconnectivity’ between migrants and their home communities” made possible by declining costs in telecommunication, travel and financial transfers.

It has been demonstrated here that mobility and frequent movement between origin and destination is an important part of the hyperconnectivity established by Indians and Chinese migration to Australia. Permanent and return migration are only the tip of the iceberg of a much larger amount of mobility. (Hugo 2008, p. 286)

According to Hugo, Australian Government thinking in migration policy is “still largely based on the centrality of permanent migration,” with poor understanding of the complexity of population movements with Asia and the Pacific.

3.6 Summary and Conclusions

Several issues have emerged from this brief survey of available theoretical literature of circular migration in Asia.

There is limited focus on theoretical approaches partly due to policy driven research and funding structures favoring empirical work. As Castles (2003) pointed out: “Because social scientists often allowed their research agendas to be driven by policy needs and funding, they often asked the wrong questions, relied on short-term empirical approaches without looking at historical and comparative dimensions, and failed to develop adequate theoretical frameworks. They gave narrow, short-term answers to policy-makers, which led to misinformed policies” (p. 26).

Initially, there was considerable research on analysis of internal population movements mostly covering rural to urban migration as a manifestation of circular mobility for Indonesia and the Pacific, among others. The phenomenon was studied mostly by geographers based on field research (Bedford 1973a, b; Hugo 1982, 1984; Goldstein 1978). The Chinese internal migration has been studied, but less from a theoretical perspective (Biao 2005).

While policymakers regarded rural-urban migration in negative terms as leading to slums and overburdening urban infrastructure, most circular migration discussions highlighted the benefits to households from this strategy. For instance, Hugo (2009a) has identified the crucial role of remittances.The early literature did not discuss links to international migration. Bedford (1973a, b) however, looked at movement of Hebrideans to other islands and also Queensland and back. Standing (1984a) also discussed links with international migration.

Most of the research has been in origin countries of Asia except perhaps, for Australia. The literature on intra-Asian migration and Gulf migration has been mostly empirical or highlighting working conditions, trafficking in persons and rights issues, especially relating to female domestic workers. Apart from Massey et al. (1998c), there has been no serious effort at discussing the theoretical issues relating to temporary migration across borders in Asia.

Only a few studies have drawn a conceptual distinction between circular migration and temporary migration. The case of Brazilian migration to Japan and that of Filipino entertainers to Japan exhibit clear patterns of circulation. The studies, especially relating to Brazilian migrants, support theories of social capital and segmented labor market theories which were claimed to be the best explanations of Gulf and intra-Asian migration as well.

The literature on the circulation of the diaspora and transnational networks has not advanced beyond empirical analysis of patterns and empirical documentation of trends.

Security of migration status in destination countries seems to play a major role in promoting circular migration since migrants enjoy the right of return.

In moving forward on theoretical analysis of circular migration, the following issues need to be addressed:

-

What is the rationale for repeat migrations, especially across borders? What theoretical approaches can explain the behavior of circular migrants? How does success or failure in previous migrations affect the probability of further migratory movements?

-

What theoretical frameworks can explain the difference, if any, between low skilled and skilled workers in regard to circular migration?

-

What are the gender implications of circular migration—are women more likely to be circular migrants?

-

What are the interfaces between internal and international circular migration?

-

What implications does circular migration have on the rights of those who move?

References

Asis, M. B., et al. (2009). International migration and development in Asia: Exploring knowledge frameworks. International Migration, 48(3), 76–106.

Bedford, R. (1973a). New Hebridean mobility: A study of circular migration. Canberra: Australian National University.

Bedford, R. (1973b). A transition in circular mobility: Population movement in the new Hebrides, 1800-1970. In H. Brookfield (Ed.), The pacific in transition: Geographical perspectives on adaptation and change (pp. 187–227). Canberra: Australian National University Press.

Biao, X. (2005). Promoting knowledge exchange through diaspora networks (the case of People’s Republic of China). A report written for the Asian Development Bank, ESRC Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford, March 2005. http://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/publications/papers/ADB%20final%20report.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

Bilsborrow, R. E., et al. (1997). International migration statistics: Guidelines for improving data collection systems. Geneva: International Labor Office.

Castles, S. (2003). Towards a sociology of forced migration and social transformation. Sociology, 77(1), 13–34.

Castles, S., & Ozkul, D. (2013). Circular migration: Triple win, or a new label for temporary migration? Paper presented at the conference on Revisiting Theories on International Migration: A Dialogue with Asia, Scalabrini Migration Center, Manila, Philippines, 25–26 April.

Chapman, M., & Prothero, R. M. (1983–1984). Themes on circulation in the third world. International Migration Review, 17(4), 597–632.

Department of Justice. (2012). Guidelines on departure formalities for international-bound passengers in all Airports and seaports in the country. Department of Justice, Government of the Philippines, Manila, 3 January 2012. http://www.immigration.gov.ph/index.php?option=com_content&task=view & id=1252&Itemid=103. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

EMN. (2011). Temporary and circular migration: Empirical evidence, current policy practice and future options in EU member states. EMN Synthesis Report. European Migration Network, Dublin. http://www.emn.ie/files/p_201111110314492011_EMN_Synthesis_Report_Temporary_Circular_Migration_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

Fan, C. C. (2011). Settlement intention and split households: Findings from a survey of migrants in Beijing’s urban villages. China Review, 11(2), 11–42.

Fan, Y.-K., & Stretton, A. (1984). Circular migration in South-east Asia: Some theoretical explanations. In G. Standing (Ed.), Circulation and the labour process (pp. 338–357). London: Croom Helm. (International Labour Office)

Goldstein, S. (1978). Circulation in the context of total mobility in Southeast Asia. Papers of the East-West Population Institute, No. 53. East West Center, Honolulu.

Hu, F., et al. (2011). Circular migration, or permanent stay? Evidence from China’s rural-urban migration. China Economic Review (UK), 22(1), 64–74.

Hugo, G. (1975). Population mobility in West Java. Ph.D. dissertation, Research School of Social Science, Australian National University, Canberra.

Hugo, G. (1982). Circular migration in Indonesia. Population and Development Review, 8(1), 59–83.

Hugo, G. (1984). Structural change and rural mobility in Java. In G. Standing (Ed.), Labour circulation and the labour process (pp. 46–88). London: Croom Helm.

Hugo, G. (2008). In and out of Australia: Rethinking Chinese and Indian skilled migration to Australia. Asian Population Studies, 43(4), 267–292.

Hugo, G. (2009a). Circular migration and development: An Asia-Pacific perspective. Multicultural Centre Prague, Prague. http://www.migrationonline.cz/en/circular-migration-and-development-an-asia-pacific-perspective. Accessed 10 Apr 2013.

Hugo, G. (2009b). Migration between the Asia-Pacific and Australia-a development perspective. Paper prepared for Initiative for Policy Dialogue, Migration Task Force Meeting, Mexico City, 15-16 January. http://www.policydialogue.org/files/events/HugoGraeme_Migration_Asia-Pacific_and_Australia_Dev_Perspective.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

Iredale, R. (2001). The migration of professionals: Theories and typologies. International Migration, 39(5), 7–26.

Khadria, B. (1999). The migration of knowledge workers: Second-generation effects of India’s brain drain. New Delhi: Sage.

Lee, S.-H., et al. (2011). Repeat migration and remittances: Evidence from Thai migrant workers. Journal of Asian Economies, 22, 142–151.

Lucas, R. E. B. (2003). The economic well-being of movers and stayers: Assimilation, impacts, links, and proximity. Paper prepared for the conference on African Migration in Comparative Perspective, Johannesburg, South Africa, 4–7 June.

Massey, D. S., et al. (1998a). Chapter 5: Labor migration in the Gulf system. In D. S. Massey & International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, Committee on South-North Migration (Eds.), Worlds in motion: Understanding international migration at the end of the millennium (pp. 134–159). Oxford: Clarendon.

Massey, D. S., et al. (1998b). Chapter 6: Theory and reality in Asia and the Pacific. In D. S. Massey & International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, Committee on South-North Migration (Eds.), Worlds in motion: Understanding international migration at the end of the millennium (pp. 160–195). Oxford: Clarendon

Massey, D. S., et al. (1998c). Worlds in motion: Understanding international migration at the end of the millennium. Oxford: Clarendon.

McLoughlin, S., & Münz, R. (2011). Temporary and circular migration: Opportunities and challenges. Working Paper No. 35, European Policy Centre, March 2011. http://www.epc.eu/documents/uploads/pub_1237_temporary_and_circular_migration_wp35.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

Monsutti, A. (2006). Afghan transnational networks: Looking beyond repatriation. Kabul: Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit.

Monsutti, A. (2008). Afghan migratory strategies and the three solutions to the refugee problem. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 27(1), 58–73.

Ong, P. M., Cheng, L., et al. (1992). Migration of highly educated Asians and global dynamics. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 1(3-4), 543–567.

Parreñas, R. S. (2010). Homeward bound: The circular migration of entertainers between Japan and the Philippines. Global Networks, 10(3), 301–323.

Piore, M. J. (1979). Birds of passage: Migrant labor and industrial societies. London: Cambridge University Press.

POEA (Philippine Overseas Employment Administration). (2012). 2007–2011 Overseas employment statistics. http://www.poea.gov.ph/stats/2011Stats.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

Sasaki, K. (2013). From breakdown to reorganization: The impact of the economic crisis on the Japanese-Brazilian Dekassegui migration system. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Comparing Regional Perspectives of Transnational Sociology, North America, Europe and East Asia, Hitotsubashi University, 22 June.

Saxenian, A. (2000). Brain drain or brain circulation? The Silicon Valley-Asia connection. Modern Asia Series Fall 2000, Harvard University Asia Center, South Asia Seminar, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, 29 September.

Saxenian, A. (2002). Transnational communities and the evolution of global production networks: The cases of Taiwan, China and India industry and innovation. Industry and Innovation (Special Issue on Global Production Networks), 9(3), 183–202.

Saxenian, A. (2011). The new Argonauts. Dublin: Global Diaspora Strategies Toolkit, Diaspora Matters.

Skeldon, R. K. (2006). Interlinkages between internal and international migration and development in the Asian region. Population, Space and Place, 12, 15–30.

Social Policy Analysis and Research Centre (SPARC). (2013). Reintegration with home community: Perspectives of returnee migrant workers in Sri Lanka. Study prepared for the ILO Office Colombo (unpublished), SPARC, Faculty of Arts, University of Colombo, Colombo, May 2013.

Standing, G. (1984a). Circulation and the labor process. In G. Standing (Ed.), Labour circulation and the labour process (pp. 1–45). London: Croom Helm.

Standing, G. (Ed.). (1984b). Labour circulation and the labour process. London: Croom Helm.

Stark, O. (1978). Economic-demographic interaction in agricultural development: The case of rural-to-urban migration. Rome: UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

Takenoshita, H. (2007). Transnationalism among Japanese Brazilian migrants: Circular migration and socioeconomic position. ASA 2007 Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 4-7 December 2007. http://www.tasa.org.au/conferences/conferencepapers07/papers/382.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

United Nations. (1998). Recommendations on statistics of international migration: Revision 1. Statistical Papers Series M, No. 58, Rev. 1, Statistics Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations, UNDESA, New York.

Verité. (2005). Protecting overseas workers: Research findings and strategic persectives on labor protections for contract workers in foreign Asia and the Middle East. Research Paper, Amherst, MA, Verité.

Wickramasekara, P. (2002). Asian labor migration: Issues and challenges in an era of globalization. International Migration Papers No. 57. International Migration Programme, International Labor Office, Geneva. http://www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/migrant/download/imp/imp57e.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

Wickramasekara, P. (2003). Policy responses to skilled migration: Retention, return and circulation. Perspectives on labor migration 5 E. International Labor Office, Geneva. http://www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/migrant/download/pom/pom5e.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

Wickramasekara, P. (2005). Rights of migrant workers in Asia: Any light at the end of the tunnel. International Migration Papers No. 75. International Migration Programme, International Labor Office, Geneva. http://www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/migrant/download/imp/imp75e.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

Wickramasekara, P. (2011). Circular migration: A triple win or a dead end. Global Union Research Network Discussions Papers No. 15. International labor Organization, Geneva, March 2011. http://www.gurn.info/en/discussion-papers/no15-mar11-circular-migration-a-triple-win-or-a-dead-end. Accessed 5 Aug 2013.

Zelinsky, W. (1971). The hypothesis of the mobility transition. Geographical Review, 61(2), 219–249.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter