Abstract

This research is the first attempt to study the wood charcoal remains for several mounds and domestic archaeological sites found in the valleys of Purén, Lumaco, and PucÓÓn, and offers information complementary to that from previous studies such as pollen deposition in wetlands near archaeological sites and the presence of carbonized fruits and seeds in archaeological contexts.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

This research is the first attempt to study the wood charcoal remains for several mounds and domestic archaeological sites found in the valleys of Purén, Lumaco, and Pucon , and offers information complementary to that from previous studies such as pollen deposition in wetlands near archaeological sites (see Chapter 6; Abarzúa et al. 2007) and the presence of carbonized fruits and seeds in archaeological contexts (Silva 2005 ms) .

The study of wood charcoal remains from archaeological or anthropic sites is called anthracology. For this science, the archaeological interest focuses on the use of wood and the transformation of the woody vegetation in areas where human communities have established (Chabal et al. 1999) . Wood charcoal forms as a by-product of incomplete combustion, which can occur as part of a natural, domestic, artisanal, or ceremonial context. The archaeological discussion of wood charcoal remains from domestic and ritual sites raises questions that are complementary to cultural research and the investigation of the traditional use of natural resources. For instance:

-

1.

Are wood charcoal remains in the kuel mounds derived from the surrounding vegetation or were these already present in the soil used in their construction?

-

2.

Are the paleobotanical patterns between kuel and domestic sites similar?

-

3.

Can the kuel–ritual association introduce a “distractive” element in the scientific interpretation of wood charcoal remains?

Material and Methods

Samples were recovered from the soil of each site using two techniques: flotation and manual sampling. Soil samples collected during the first season of excavation were floated in a column of sieves that were 2, 1, and 0.5 cm in size. During the next field season, the recovery of macrobotanical specimens was done using a flotation machine. Sampling by hand was found to be a less effective technique and was only used to gather traces of charcoal (patina) on clayish soils of the kuel (LU-19, PU-166) and a domestic site (PU-132).

The analysis of the charcoal was done using an Olympus BX60 optical microscope, equipped with refracted and polarized light. Identification was supported by comparing the material with samples from the reference collection of carbonized wood samples of plant and tree species commonly found in the temperate forests of southern Chile and available wood anatomy books of Chilean species (Wagemann 1949; Rancusi et al. 1987; Solari 1993; among others) . Fragments were manually snapped along three planes (transverse, longitudinal radial, and longitudinal tangential). This made the observation of taxonomically important features in the fragment’s anatomy easier.Footnote 1 These anatomical features also allowed classifying the samples as members of gymnosperms, angiosperms, or monocotyledons.Footnote 2

The analysis of the wood charcoal remains from the sites of Purén, Lumaco, and PucÓn also involved the description of complementary characteristics, both microscopic and macroscopic, such as dimensions of the fragment, presence of foreign intrusions, and vitrification.

Results

Vegetation Description for Each Site Zone

Historically, the vegetation around the archaeological sites in the Purén Valley corresponds to the transition forest type found in the Cordillera de Nahuelbuta. Common species found there are Nothofagus obliqua (roble), Nothofagus dombeyi (coigüe), Laurelia sempervirens (laurel), Aextoxicon punctatum (olivillo), Eucryphia cordifolia (ulmo), Gevuina avellana (avellano), and also sclerophyllic species such as Cryptocarya alba (peumo) and Lithraea caustica (litre), among others. In contrast, Lumaco is located on the plains and is surrounded by park-like vegetation that is typical of northern Cautin. These plains were subjected to slash and burn practices to create fields for cultivation and stock raising. Nowadays, this broad zone is extensively covered by plantations of Pinus radiata (Monterrey pine) (Donoso 1993) . Three wood fragments with anatomical characteristics similar to this species found in the site suggest the inclusion of this species in the archaeological site LU-34 (Mound G, Stratum 2). Finally, PucÓn is located in the ecotonal zone of the Araucanian lakes of the Andes. Common tree species found there are Nothofagus obliqua (roble), Nothofagus alpina (rauli), and Nothofagus dombeyi (coigüe), along with Laurelia sempervirens (laurel), Persea lingue (lingue), and Aextoxicon punctatum (olivillo) (Donoso 1993) .

Analysis of Wood Charcoal Remains

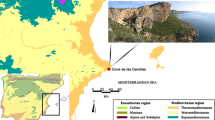

A total of 138 wood charcoal fragments were analyzed. These are from the sites in Lumaco (75 fragments), PucÓn (52 fragments), and Purén (11 fragments) that are represented by kuel and domestic sites (Fig. 14.1). The samples cover a broad period of time (AD 1000–1900).Footnote 3

Before presenting the results of the wood charcoal remains, it is important to indicate that the identification and quantity of fragments found in each site can be affected by the following:

-

Fragmentation of the remains. Fragments are generally smaller than 5 mm, producing an overrepresentation of the species, for example, in the kuel LU-34, level 90–102 (Nothofagus obliqua), and the domestic site PU-165, level 33 cm (Myrtaceae family that includes the species arrayan or Chilean myrtle).

-

Presence of very fine lenses of charcoal. These are less than 2 mm and the final product of intense fragmentation (e.g., by trampling on the site), which makes identification difficult, increasing the number of unidentifiable charcoal fragments (e.g., PU-165).

-

Small size of the fragments in both the ceremonial and domestic sites. These fragments are much smaller than those observed in other analyses (> 1 cm). They range from 1.2 to 0.3 mm in length with an average width of 0.4 mm.

Wood Charcoal Remains from Kuel or Ceremonial Sites

The taxonomic diversity of the kuel (Fig. 14.2) was obtained from the number of charcoal fragments identified in each site and the floristic richness of each area. The Valley of PucÓn is located in the Andes and this area has a larger number of taxa (12 charcoal samples)Footnote 4 than the transitional sector between the Coastal Cordillera and the Central Valley where Purén (4) and Lumaco (8) are located (Fig. 14.3).

The analysis of eight samples from the Lumaco mound indicates the presence of thirty-five fragments of Nothofagus obliqua (LU-34, Mound G, Stratum 2, levels 80–95 and 90–104). Similarities in the anatomy and growth rings suggest the fragmentation of only a few pieces of wood charcoal, including the following:

-

A series of unidentified charcoal fragments (unidentifiable, undetermined, bark).

-

The low frequency of Aristotelia chilensis and Aextoxicon punctatum, both species of the temperate forest.

-

Wood from an introduced species, Pinus radiata, found during the preparation of the profile of LU-34, Mound G, Stratum 2 (Fig. 14.3).

The mound site from Purén (PU-166, Kuel 8) has wood charcoal from four taxa. These taxa are Aristotelia chilensis, Proteaceae, and unidentified charcoals (unidentifiable, vitrification fragments). Meanwhile, the five samples from the site in PucÓÓn show the greatest floristic richness, with an almost complete representation of the species found in the temperate forest of the Andes. Some of the species are Persea lingue, Aextoxicon punctatum, a member of the family Myrtaceae, and species of vines and the genus Chusquea. This result is probably related to the lower human impact in this environment (the paleoenvironmental scenario) or to more intense and frequent episodes of burning on the kuel (archaeobotanical scenario).

Domestic Sites

The domestic sites are concentrated principally in Purén (PU-165, PU-132, and PU-87). They are absent in PucÓn and there is only one site in Lumaco (LU-16), but many of the remains were identifiable. The taxonomic diversity of the wood charcoal remains in Purén is represented in Fig. 14.4. From all the taxa identified here, the presence of a representative of the Myrtaceae family is noteworthy (21 fragments). Members of this family are generally found in wetlands or in gallery forests associated with watercourses. This suggests that in Purén, these areas were used as places for gathering firewood for domestic use. Other species present are Nothofagus obliqua–alpina (6 fragments), Persea lingue (1 fragment), Aristotelia maqui (2 fragments), Aextoxicon punctatum (8 fragments), an unidentified angiosperm (15 fragments), and a species of the Proteaceae family (1 fragment).

There was a difference between the number of taxa recovered from the domestic sites (82 %) and the kuel in Purén (18 %). This difference is in direct relationship to the number of samples found on each site (10/2) and the amount of charcoal analyzed (Figs. 14.4 and 14.5).

Unidentified Wood Charcoal Remains

With the aid of a dissecting microscope, the presence of small charcoal particles incorporated in very friable soil was corroborated (e.g., LI-19, Mound G). These could be charcoal fragments already present in soil carried to the kuel for construction or the product of the further breakage of these fragments through intensive trampling. These fragments were not counted and their presence was only noted.

The samples from the Maicoyakuel mound site (PU-220, levels 70–80, 74, 99, 196, 230–235, and 275–285 cm) that consist of traces of charcoal on red clay had no wood charcoal fragments suitable for identification. These traces can be produced by continuously trampling on small charcoal fragments. This can cause black spots of small diameter. Similar spots were observed in some of the samples from kuel PU-166 and in the domestic site PU-133 (levels 27, 33, 41, 42, 46, 48, 51, 60, and 62 cm).

Another difficulty encountered in the identification of the samples was the vitrification of fragments of small diameter (< 2 mm), which were found at the following Pucon sites: LI-12A, LI-2A, LI-19, and PU-87. The extent of anatomical modification shown by the wood exposed to the process of pyrolysis and its characteristics have been studied before, but so far, there is no consensus among scholars about the causes of these changes.Footnote 5 In this case, these samples correspond to wood charcoal fragments of small diameter derived from species of angiosperm.

The category of unidentifiable mainly includes charcoal fragments of poor condition or smaller than 2 mm. The percentages of unidentified charcoal fragments were similar between PucÓn (41 %) and Lumaco (43 %), both with a significant number of samples from ceremonial sites, while Purén has a larger number of domestic sites, with bigger, easily identifiable, wood charcoal fragments (Fig. 14.6).

Anatomical Identification of the Samples

The list of families, species, and taxa present in the sites studied, belonging to the domain of the temperate forest of the south-central region of Chile (e.g., Lehnebach et al. 2008; Solari and Lehnebach 2004; Zucol 2000) , which extends to the zone of PucÓ n , are listed and described in Table 14.1 (see Fig. 14.7).

Conclusions

It is interesting to evaluate the results obtained here with the questions on cultural and paleoenvironmental investigations presented earlier in this study. With regard to the number of charcoal fragments recovered, it is still necessary to further investigate whether the sampling methodology is adequate. This would require the implementation of a different protocol for each type of site (domestic or ceremonial) and the features of the fragments (dispersed or concentrated).

Despite the taxonomic richness between the samples from the kuel in the highland region of PucÓn and the domestic sites of Purén being similar, establishing a clear paleoenvironmental scenario for both types of sites is impossible. Furthermore, the landscape in which these sites are found needs to be kept in mind. The valleys have been affected by human use to some or the other extent. Early chroniclers and historians like Camus (2006) and Bengoa (2003) , respectively, describe these as “cleared lands” within the temperate forests of southern Chile associated with agriculture and extensive settlement.

The ceremonial sites present two types of charcoal fragments:

-

Small samples of macroscopic wood charcoal , the product of individual fires, occurring in the different soils and use trampled surfaces of each kuel.

-

Charcoal fragments smaller than 1 mm and unidentifiable microfragments, with the patina of the sediment of which they form a part; it is probable that these fragments were incorporated into the soil beforehand and were brought in it to build the kuel.

Another question to explore is related to the possible presence of species with ethnographically known ritual importance , such as Drimys winteri (canelo). This species was not found within the identified samples; however, the presence of Nothofagus was very frequent, especially the deciduous species commonly found in this area (e.g., roble, pellín, and cf. raulí). These species have a ritual importance in the ceremonies conducted in the kuel, and they are planted around some of these structures. It is possible that canelo and other species are present among the unidentifiable charcoal samples.

Notes

- 1.

Microscopic identification of the wood charcoal did not always lead to the identification of the material at species level. This was subject to anatomical features within a particular genus, which can be affected by hybridization; in this case, both species are indicated (Nothofagus obliqua–alpina), or when less certain, the sample was given a comparative qualifier and cf. is indicated before the name (e.g., cf. Laurelia sempervirens). If the identification is only to generic level, the abbreviation sp. is written after the genus (e.g., Nothofagus sp.). Given the great variability within the identifications, the whole group is called taxon and includes all the previous categories as well as the families (i.e., Proteaceae and Myrtaceae).

- 2.

Gymnosperm with secretor channels.

- 3.

Radiocarbon dates and relative dating of ceramics.

- 4.

It is hypothesized that the impact of human activity in PucÓn was lesser on the natural landscape.

- 5.

The subject was discussed in the workshop in Rennes, France (2001), and no consensus was reached regarding the cause of crystallization—vitrification of the samples. For some, this is associated with the type of species and their components, while for others, it is related to the small diameter or combustion of the material

References

Abarzúa, A. M. A., Jarpa, L., Martel, A., Vega, R., Pino, M. (2007). Informe trabajo realizadoen el Valle de Purén Lumaco. Instituto de Geociencias, UACh.

Bengoa, J. (2003). Historia de los antiguos mapuches del sur. Desde antes de la llegada de los españoles hasta las paces de Quilín. Santiago: Ed. Catalonia.

Camus, P. (2006). Ambiente, bosque y gestión forestal en Chile: 1541–2005. Santiago: Ed. Lom.

Chabal, L., Fabre, L., Terral, J. F., Théry-Parisot, I. (1999). L’anthracologie. In C. Bourquin-Mignot, et al. (ed.), La Botanique (pp. 43–104). Paris: Editions Errance.

Donoso, C. (1993). Bosques templados de Chile y Argentina. Variación, estructura y dinámica. Santiago: Ed. Universitaria.

Hoffmann, A. (1982). Flora silvestre de Chile. Zona Araucana. Ärboles, arbustos y enredaderas leñosas. Santiago: E. Fundación C. Gay.

Lehnebach, C., Solari, M. E., Adán, L., Mera, R. (2008). Plant macro-remains from a rockshelter in the temperate forests of Central-South Chile (39° S). Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 17, 403–413.

Rancusi, M., Nishida, M., Nishida, H. (1987). Xylotomy of important Chilean woods. In M. Nishida (ed.), Contributions to the botany in the Andes II, (pp. 68-158). Tokyo: Ed. Academia Scientific Book.

Silva, C. (2005). Informe de análisis carpológico sobre muestras provenientes desde los cuel de Lumaco y Purén. Región de la Araucanía. Report submitted to the Proyecto Purén-Lumaco, Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University.

Solari, M. E. (1993). L’homme et le bois en Patagonie et Terre de Feu au cours des six derniers millénaires: recherches anthracologiques au Chili et en Argentine. Thèse de Doctorat. Université de Montpellier II.

Solari, M. Eugenia, & Lehnebach, C. (2004). Pensando la antracología para el centro-sur de Chile: Sitios arqueológicos y bosque en el lago Calafquén (IX-X región). Revista Chungará, 1, 373–380.

Wagemann, W. (1949). Maderas chilenas: contribución a su anatomía e identificación. De Lilloa, XVI, 304–350.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Solari, M. (2014). Appendix 3: Analysis of Wood Charcoal Remains from Kuel and Domestic Sites. In: The Teleoscopic Polity. Contributions To Global Historical Archaeology, vol 38. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03128-6_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03128-6_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-03127-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-03128-6

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)