Abstract

This chapter explores spatial inequity in under-five mortality in Nigeria through the lens of key social development factors across states evident in maternal educational attainment, wealth distribution, and access to maternal healthcare services. Trends and temporal patterns of under-five mortality from 2008 to 2018 using the Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys data were compared descriptively with key variables in the different states. It found that the high rate of under-five mortality in Nigeria is largely due to high infant mortality, particularly in the first month of life. Hence, there is a need to expand programs targeted at protecting children during the first year of life.

Findings further suggest that under-five deaths were higher in the North East and North West zones. The most regional progress made over the period was in the South East and South South. Results further showed that even though states within a geo-political zone had some level of homogeneity, within-zone analysis confirmed wide variations between states in the same geo-political zone, as well as varied temporal patterns between 2008 and 2018. While under-five mortality declined in some states, it increased in several others.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Under-five mortality

- Temporal pattern

- Socio-economic factors

- Trend

- Health and development

- Maternal and child health

1 Introduction

Early childhood mortality, also referred to as under-five mortality, is a critical indicator of child health, socio-economic development, quality of life, and the general health of a population group (National Population Commission Nigeria [NPC] & ICF International, 2019; Van Malderen et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2014). Under-five mortality is a focus of global action, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs), because children face their highest risk of death during this period, particularly in infancy. Early childhood mortality is also linked to fertility and population growth (Preston, 2007), with Rosling (2006) arguing that improving child survivorship reduces fertility and population growth in the long run. Globally, early childhood mortality reduced by 77% between 1950 and 2015 (United Nations, 2017). While the European region had the most rapid decline in under-five mortality (93%), improvements have been more muted and patchier in Africa, where under-five mortality reduced by 71%, with noticeable variations between countries (United Nations, 2017).

The situation in Nigeria is particularly dire. While some of the least-developed African countries have seen remarkable improvements in under-five mortality, Nigeria has worsened in recent years. It now has the world’s second highest under-five mortality rate (UN, 2019). The state of child health in Nigeria cannot be attributed solely to economic factors. Countries such as Rwanda, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, and Niger have less economic endowment and recent civil war experiences have worsened their economic and political situations, yet they fared better than Nigeria in early childhood survival outcomes. Nigeria has a more robust economy, yet early childhood mortality has remained stubbornly intractable over the last decade. Unfortunately, one in every eight children in Nigeria die before their fifth birthday and more than half of those deaths are attributed to conditions that could be prevented or treated with timely access to affordable interventions such as maternal and child health care, proper handling of pregnancy-related complications, childhood vaccination against infectious diseases, and availability of basic amenities (Ezeh et al., 2015; NPC & ICF International, 2019; Ojewumi & Ojewumi, 2012).

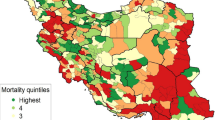

Given the extensive research that has been carried out on maternal and child health in Nigeria, coupled with the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) and SDGs to meet set targets, one would expect early childhood mortality in Nigeria to have reduced appreciatively in recent decades. However, the 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) showed that early childhood mortality in the 5 years preceding the survey increased to 132 deaths per 1000 live births, up from the 2013 NDHS figure of 128 deaths per 1000 live births (NPC & ICF International, 2019). This increase is a reversal of previous gains, where under-five mortality in Nigeria reduced from 201 to 157 deaths per 1000 live births between 2003 and 2008 (NPC & ICF International, 2004, 2009; UNICEF, 2018). The state of child health sub-nationally, as shown in Fig. 15.1, is even more worrisome given the vast differences in early childhood mortality.

Under-five mortality by State for the 10-year period preceding 2018 NDHS. (Source: NPC and ICF International, 2019)

Nigeria’s high childhood mortality is indicative of the poor quality of health for the average Nigerian. Without an enabling environment, including access to basic health facilities and social amenities, individual health outcomes are greatly impaired, especially for children under the age of five. Evidence suggests that provision of affordable and accessible maternal and child health care by the government is a major step in reducing health inequality and helping Nigeria meet SDG target 3.2 by 2030 (Ojewumi & Ojewumi, 2012; Rutherford et al., 2010). In Rwanda, which had a very similar level of under-five mortality to Nigeria in 2000, adequate coverage of maternal and child health from the government helped it achieve a 70% reduction in under-five mortality between 2000 and 2011 (Amoroso et al., 2018).

This chapter provides an in-depth examination of the persistent inequities in under-five mortality between states in Nigeria, with a particular focus on exploring the extent to which persistently high levels of under-five mortality can be explained by the changes in key socio-economic factors over time. Examining spatial changes in early childhood mortality is crucial in adding knowledge to the literature and providing evidence-based results that will aid the government and health policymakers in implementing programmes that can address the underlying drivers of under-five mortality. The specific objectives for this study were to: (1) examine changes in under-five mortality in Nigeria from 2008 to 2018, (2) provide a fine-grained spatial analysis of relative changes in under-five mortality over the study period, and (3) determine whether there are associated variations by state in the key socio-economic development factors of interest over time.

2 Literature Review

While a significant number of studies have examined poor child survival outcomes in Nigeria, they are mainly focused on the geo-political zones with little attention paid to states. As such, there is a lack of understanding about how state-level factors might be associated with under-five mortality. It is known that there is a clear north-south divide in under-five mortality rates in Nigeria, with the northern regions having higher rates than the south (Adedini, 2013; Antai, 2011). In the 2018 NDHS (Table 15.1), under-five mortality over a 10-year period in Nigeria exceeded 100 deaths per 1000 live births in the North West and North East (187 and 134, respectively) but was below 100 in the southern regions (75, 73, and 63 deaths per 1000 in South East, South South and South West, respectively). Table 15.1 also shows further gaps in under-five mortality amongst Nigeria’s 37 states, with intra-zonal state variation, showing that even within the same geo-political zone, some states have substantially better or worse under-five mortality rates than the zonal average. This highlights a major limitation in only undertaking analysis at the national or zonal level.

Identifying all the causes of under-five mortality is daunting given the complexity of the situation. Biological, economic, social, and environmental factors at the individual, household, and community levels play different roles, either directly or indirectly, on the chances of survival of a newborn (Adebowale et al., 2017; Antai, 2011; Koffi et al., 2017; Sastry, 1996). This chapter focuses on key social determinants of health at the state-level such as mother’s level of education, household wealth status, antenatal visits (ANC), place of delivery, and assisted delivery.

The role of individual/household socio-economic status on child health outcomes cannot be overemphasized. Studies have identified several individual/household background characteristics that act as indirect determinants of under-five mortality, including mother’s education, and wealth status (Akinyemi et al., 2015; Ettarh & Kimani, 2012; Kayode et al., 2012; Koffi et al., 2017; Rutherford et al., 2010; Rutstein et al., 2009; Yaya et al., 2017). Factors at the communities, beyond the individuals and households, also form external structures that operate through these determinants. For instance, if maternal women have the right education and information and can access quality health care, some pregnancy- and childbirth-related anomalies and death can be prevented. Studies published in The Lancet showed that access to improved health care, quality drinking water, and improved toilet facilities are essential in improving child survival, especially for those in areas with increased exposure to infection due to their household’s socio-economic status (Ezeh et al., 2017; Lilford et al., 2017). Children below the age of five have lower immunity and providing optimum conditions at this stage are crucial for enhancing their survival outcomes.

The wealth index of a household determines the resources available to a child, the type of house a child is raised in, and access to health care, thereby indirectly influencing under-five mortality (Blackstone et al., 2017; Ezeh et al., 2015; Rutherford et al., 2010). The household wealth quintile measures impact on the health of the child through a measure of the scale of social class differences in a society. Likewise, inequalities in wealth distribution and educational attainment in the household create social class separation, which impacts on access to healthcare services (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2006). In Nigeria, wealth inequalities clearly create accessibility barriers to healthcare services in ways that impact negatively on early childhood survival outcomes (Koffi et al., 2017; Ojewumi & Ojewumi, 2012).

Nigeria has high income inequality with huge gaps between the rich and the poor, where Gini coefficient worsened from 0.35 in 2004 to 0.41 in 2013 and improved slightly to 0.39 in 2016 (NBS, 2018). As shown in Table 15.2, there is disparity in headcount per poverty measure across states. The northern zones with higher poverty rates also have higher under-five mortality rates when compared with the southern zones, and states with lesser income have lower capacity to finance social services at the macrolevel. As pointed out by previous studies, the link between poverty and under-five mortality is bolstered by the poverty rate in different states in Nigeria (Ahmed, 2007; Fotso, 2006; Hong et al., 2006; Sanders & Carver, 1985).

In many developed and developing nations, an increase in GDP is usually followed by investment in education, healthcare and social services, resulting in improved child survival (Rosling, 2006). This is not the case in Nigeria. Instead, the country has experienced persistently high under-five mortality rates despite a steady rise in GDP from the 1990s as shown in Fig. 15.2. Studies have shown that mortality decline, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, can be largely sustained through improvement in standards of living and public health measures such as clean drinking water, sanitation, and public health education (Wilmoth, 2003). However, Rosling (2006) cautioned that improved health outcomes do not happen automatically, but rather are products of governmental development policies in social, educational, and health services. This implies that broad socio-economic development in Nigeria, and Africa at large, can be sustained by improvements in child health. With more than half of its population aged 15 to 65 years, Nigeria has the potential to witness accelerated development and capitalize on its ‘demographic dividend’ (Bloom et al., 2003). However, this requires that the government make investments in education and heath a priority, while providing an enabling environment for continuous economic growth (UN-DESA, 2019). This can be done through provision of quality and affordable education up to secondary level, provision of health services and basic social infrastructure, as well as creation of more job opportunities and support for private enterprise.

Nigeria’s GDP per capita with aggregates. (Source: World Bank, 2019)

The conceptualization of this chapter is from the underlying premise that socio-economic factors strongly influence variations in under-five mortality. This influence occurs indirectly. Variations in socio-economic development at the state-level enable inequality in the socio-economic status of individuals and households. Variations in individual and household socio-economic status play a central role in shaping the proximate determinants of mortality amongst under-five children. Clearly, inequalities in place of residence (rural, urban), and between and within states, are associated with child survival outcomes in Nigeria. Possible explanations are poor socioeconomic factors within the state and inability of households with low income to pay for health services in the absence of universal health care, especially for maternal women and children below the age of five.

3 Data and Methods

The data used in this study is sourced from the 2008, 2013 and 2018 NDHS, which are the three most recent ones carried out by the National Population Commission, Nigeria. ICF International provided technical assistance for the surveys through the DHS Program, with funding from United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (National Population Commission (NPC) Nigeria & ICF International, 2009, 2014, 2019). NDHS is a nationally representative household survey designed to provide population and health data from regular households at the national, geo-political and state levels.

For administrative purposes, Nigeria is divided into 37 states (36 states plus the Federal Capital Territory), with the states further divided into 774 Local Government Areas (LGAs), and LGAs into localities. From the localities, smaller units called Census Enumeration Areas (EAs) were created during the 2006 Population and Housing Census. The 2008, 2013 and 2018 NDHS primary sampling units (PSUs), referred to as clusters, are defined based on the 2006 EA census frame. The sample selection for the surveys involved a two-stage stratified sample design, where the 37 states were separated into urban and rural (based on the 20,000-population threshold for urban area) making a total of 74 sampling strata, from where samples were selected using a two-stage selection per stratum. The number of households was distributed proportionately amongst urban and rural areas in each state during each survey, while interviews were completed from women aged 15–49 years who were either permanent residents or visitors who spent the night before the survey in the selected households in 2008, 2013 and 2018 NDHS, respectively (National Population Commission (NPC) Nigeria & ICF International, 2009, 2014, 2019). Further information on questionnaire design, sample design, data collection, analysis and other implementation strategies of the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey can be found in the final reports (National Population Commission (NPC) Nigeria & ICF International, 2009, 2014, 2019).

3.1 Analytical Strategy

The analyses examine trend and patterns of under-five mortality in Nigeria from 2008 to 2018 and compare them with changes in the key study variables (mother’s level of educational attainment, household wealth status, antenatal visits, place of delivery and assisted delivery), to ascertain if these factors contributed to spatial variations in under-five mortality in Nigeria. Women aged 15–49 years with at least a live birth within the 5 years preceding each survey are included in the analysis, with the unit of analysis being children born in the 5 years preceding the surveys. The 5-year reference period is necessary to limit recall bias to explore recent events and provide a more accurate information. Under-five mortality or early childhood mortality is the probability of a child dying between birth and fifth birthday if subject to age-specific mortality rates at the time of birth (Adedini, 2014; NPC & ICF International, 2019). Respondents were asked if they had children who were born alive but later died, and the age at death. Age at death is used to estimate early childhood mortality. As children die at different rates during the childhood period, with the highest mortality during the first year of life, to provide more robust analyses, the outcome variable is disaggregated into two stages of childhood development.

-

1.

Infant death: Number of deaths before the first birthday

-

2.

Child death: Number of deaths between the first and fifth birthday

4 Results

This section focuses on results from the trends and patterns of under-five deaths and study variables in Nigeria, paying particular attention to inter-regional, intra-regional and inter-state variations. Prior studies of early childhood mortality in Nigeria have shown that the risk of death is highest in the first year of life, largely due to high neonatal deaths in the first 27 days (Ekwochi et al., 2015; Fetuga et al., 2007). Consistent with these findings, Fig. 15.3 shows the risk of early childhood mortality in Nigeria is higher in infancy, both nationally and sub-nationally. Throughout the focal period, infant (0–11 months) mortality was almost double that of childhood mortality (12–59 months). As reported in NDHS 2013, 70% of under-five deaths occurred at infancy. Also, there was a marked increase in the proportion of deaths that occurred at infancy from 2008 to 2013, while deaths in childhood reduced in the same period. Infant deaths reduced marginally from 2013 to 2018, with a contrasting increase in child deaths in the same period. Remarkably, the distribution of death for these indicators remained almost static from 2008 to 2018 at the national level. Whatever improvement (in the case of childhood mortality) or loss (in the case of infant mortality) was made in 2013 became almost insignificant in 2018. Infant deaths increased from 64% at the onset of the study period in 2008 to 66% at the end of the period in 2018, while child deaths reduced from 36% in 2008 to 33% in 2018. Figure 15.3 clearly highlights the little progress made in improving child survival over more than a decade in Nigeria.

Subsequent analyses focus on vital aspects of this chapter – levels, trends and differentials of infant and child deaths by geo-political zones and states. Findings on under-five mortality at the sub-national level are discussed in the light of the key study variables observed in different geo-political zones and states. This level of analysis is important to raise awareness about the situation at the zonal and state levels and shed light on how they relate to sub-national disparities in early childhood survival.

4.1 Levels, Trends and Differentials in Under-Five Mortality by Geo-political Zones

There exist vast differences in early childhood survival outcomes between and within the six geo-political zones that cannot be ignored. Exploring these zonal differences helps in identifying unique background characteristics within the zones that might be associated with under-five mortality, thus providing a more strategic view on under-five mortality in Nigeria. Inter-zonal differences in maternal education, religion and cultural practices have been identified in past studies as possible drivers of these differences (Adedini et al., 2015a, b). Disaggregation of infant and child deaths by geo-political zones as depicted in Figs. 15.4 and 15.5 not only reveals inter-zonal differences but also a clear north-south divide. Consistent with other studies, under-five mortality rates are substantially higher in the northern geo-political zones than in the southern parts (Adebowale et al., 2012; Adedini et al., 2015a). The figures illustrate that the northern regions reported increased infant and child deaths from 2013 to 2018, except for child deaths in North East from 2013 to 2018 as shown in Fig. 15.5. This is an indication that these regions contributed significantly to the increase in under-five mortality observed at the national level from 2013 to 2018. In contrast, early childhood deaths in the three southern regions declined steadily throughout the study period.

Although under-five mortality was highest in the North West in all three survey points, the increase in 2018 is particularly noteworthy because under-five mortality had declined significantly in the previous period. A possible explanation for this reversal could be the increase in internal migration from the neighbouring North East region, due to increasing insecurity in the region because of activities of the terrorist group, Boko Haram. These terrorists have killed thousands of people, displaced or captured hundreds of thousands more, destroyed social and health infrastructures and paralysed economic activities in the North East (Adamu et al., 2021; Ager et al., 2015; Dunn, 2018). It is possible that the activities of the terrorist group may have created an existing health burden on the children, coupled with lack of health care and challenges with being displaced, thereby leading to their death on arrival at their new destinations.

The geo-political zone comparisons also reveal notable progress in the South East. Infant deaths were almost at par with the North East in 2008 and higher than North Central in 2008 and 2013, but it declined slowly in the zone in 2013 and then sharply in 2018. However, South East still had the highest proportion of child deaths in the southern region at 1.9%. All zones made clear progress in reducing under-five deaths from 2008 to 2013, although the trend was more muted in the South West.

Tables 15.3 and 15.4 further present Chi-square (chi-2) tested results and percentage changes in under-five deaths by geo-political zones. The results showed significant relationships between under-five deaths and geo-political zones throughout the study period, suggesting that factors within the geo-political zones are relevant in studying under-five mortality in Nigeria. In assessing the percentage change in early childhood mortality over time, Table 15.3 shows that the overall highest reduction in infant deaths was reported in the South East. In contrast, the North West had an increase of 5.4% between 2008 and 2018. Table 15.4 shows that South South made the most overall improvement with more than 50% decrease in child deaths, while North West made the least. Generally, there was more progress made in reducing child deaths than infant deaths.

4.2 Levels, Trends and Differentials in Under-Five Mortality by States

State-level variations and intra-zonal differences amongst states in the same geo-political zone are important to highlight. One of the key contributions of this research is not only to explore variations between zones, but also to highlight variations in under-five mortality amongst states in the same geo-political zones. As other scholars have shown, there are state-level differences across a wide range of human development outcomes that do not map neatly onto geo-political zones (Adedokun et al., 2017; Ayoade, 2020; Olorunsaiye & Degge, 2016). Tables 15.5 and 15.6 present more granular spatial analysis of levels, trends and differentials in infant and child mortality in Nigeria. Percentage changes in under-five deaths pinpoint critical lows and highs for each state across the period, by showing the size of change in under-five deaths. These patterns help in identifying states where current programmes need to be sustained and those that require urgent attention.

While analysis at the regional level provides some insight into the sub-national dynamics, a closer look inside regions shows noticeable differences in under-five mortality with visible peaks and troughs across states, emphasizing the need for sub-national analysis at the state- level. Spatial analysis ensures accountability at the state levels, since provision of primary health care is largely managed by the state and local governments (Adedini, 2013; Ogbuoji & Yamey, 2019). Chi-2 tested results in Tables 15.5 and 15.6 indicate that structures at the state- level are significantly associated with under-five mortality in Nigeria. When the states were ranked from the least to the highest percentage of infant deaths, Kaduna went from being the 21st state in 2008 to the state with the highest infant deaths in 2018 with 11%, even worse than Imo’s fig. (10.54%) in 2008, when it had the highest infant deaths. In contrast, Ogun progressed from being the 20th state in 2008, just one step ahead of Kaduna, to recording the lowest rate of 1.6% in 2018. This result highlights the vast disparity in infant deaths amongst states.

In the North Central, Benue and the FCT made the most progress, while Kwara made the least. Results also show that Kogi went from 30% mid-point decrease to more than 100% increase in infant deaths from 2013 to 2018. Amongst the North East states, Adamawa and Borno recorded marked reductions in infant deaths from 2008 to 2013, which was visible at the regional level, while the other states in the region made no visible progress at the time. Nevertheless, Borno and two other states in the region recorded an increase in infant deaths from 2013. What little progress had been made in the North West from 2008 to 2013 was cancelled out by increase in infant deaths from 2013 to 2018 in more than half of the North West states. To put this in context, Kaduna went from a 48% reduction in infant deaths from 2008 to 2013, to more than 200% increase between 2013 and 2018.

Moving on to the southern states, infant mortality rates for all the states in the South East reduced between 2008 and 2018, reinforcing what was seen at the regional level, especially the progress reported in Imo, which had the highest infant mortality rate in 2008. Only Anambra reported an increase in infant deaths from 2008 to 2013, which was subsequently followed by a 50% reduction between 2013 and 2018. In the South South, improvements seen earlier at the zonal level from 2008 to 2013 can be attributed to the individual reductions in infant deaths seen in the states in Table 15.5, especially those of Bayelsa and Edo. However, Edo’s progress was not sustained, as infant mortality deteriorated between 2013 and 2018. Finally, in the South West, Ogun with more than 70% decrease recorded the most progress at reducing infant deaths, while Osun with more than 80% increase recorded the least. Intra-state dynamics during the study period culminated in the muted progress seen earlier at the South West zonal level.

Child mortality analysis by state in Table 15.6 consolidated the pattern seen in infant mortality results, where states in North East and North West reported the highest rates. When ranked from the least to the highest child deaths as well, Cross River went from being sixth in 2008 to the state with the least reported child deaths in 2018 at 0.4%, whereas Kebbi went from the 22nd position amongst 37 states in 2008 to reporting the highest rate of child death (7.7%) in 2018.

In North Central, Benue and Niger made the most progress, while Kogi made the least. It can also be seen that Kogi and Plateau had more than 100% increase in child deaths between 2013 and 2018. Only Taraba recorded an overall increase in child deaths amongst states in the North East, with Adamawa and Borno also recording the highest decrease. The rapid fall and rise in child deaths observed in the North West earlier in Fig. 15.5 is clearer from intra-zonal and intra-state patterns shown in Table 15.6. All the North Western states made progress between 2008 and 2013 but dropped from 2013 to 2018 with the exceptions of Sokoto and Zamfara. The table further shows from 2008 results that the North West had such poor childhood survival rate that even Zamfara with the lowest percentage in the zone was still higher than childhood survival results from the southern zones.

Child mortality rates for all the states in the South East reduced between 2008 and 2018. Abia with 81% reductions in deaths made the most progress in the zone, while Imo with 5% reductions made the least. South South states also progressed substantially, with all the states recording overall reductions in child deaths. Akwa Ibom made the most progress, while Edo with 20% reductions in child deaths made the least. Going further to the South West, only Oyo state with a 29% increase in child deaths did not report reductions in child deaths throughout the focal period. Surprisingly, Ekiti went from reporting a 75% decrease in child deaths between 2008 and 2013 to more than 200% increase between 2013 and 2018.

Overall analysis of under-five deaths in Nigeria indicates that in over a decade, most states in the country are still around the same place. These findings confirm that we have not progressed to the point where we can say as a country that we have made a positive shift in improving under-five mortality that can be escalated to the state level. To this end, strategic actions are needed by government at all levels, if Nigeria is to make progress in improving early childhood survival.

Having examined spatial variations in under-five mortality over a decade, this chapter proceeds to explore the spatial distribution of key variables over the same period. Sub-national distribution of the study measures, showing different dynamics across the country and their changes over time from 2008 to 2018, provides an enhanced understanding of the trend and rate of socio-economic development across the country. This level of information, often hidden in studies that only disaggregate to the regional level, would help programmes and research on the persistently high sub-national inequality in under-five mortality in Nigeria.

4.3 Summary of Trends in Maternal Educational Attainment

Results on mother’s education amongst children born within 5 years of the surveys show higher rates of illiteracy amongst women in the northern region during the period under study. Figure 15.6 indicates a reduction in the proportion of children born to women with no formal education across all the regions with an attendant increase in secondary and higher levels educational attainment. But North West consistently had the highest levels of no education across the period at 78, 77 and 73% in 2008, 2013 and 2018, respectively, while South East had the lowest at 3% in 2018. Most recent result in 2018 reveals that 20% of the children in the South West were born to women with higher education, which was the highest percentage of those with higher education in the country, in contrast to only 3% in the North West.

State analysis across the period as shown in Figs. 15.7, 15.8 and 15.9 further highlights the contributions of the different states to changes in educational attainment seen at the regional level. There was a high concentration of children born to women without formal education in the northern states. Sokoto state (North West) at 93% had the highest proportion of children born to women with no education in 2018, while Imo state (South East) with less than 1% had the lowest. Generally, Lagos state (South West) with 30% had the highest proportion of children born to women with higher education. Improvements in educational attainment could be seen from the figures, as the proportion of children born to women with secondary or higher education improved across the board from 2008 to 2018.

4.4 Summary of Trends in Household Wealth Quintile

As illustrated in Fig. 15.10, the proportion of children born into households in the highest wealth quintile in the six geo-political zones increased over time, with an associated reduction in children born in households in the lowest quintile. The only exception was in South East, where there was a marginal 1% increase in the proportion of children in the poorest households from 2008 to 2018. Higher wealth inequality was evident in the North East and North West zones in 2018 – less than 20% of the children belonged to households in the two upper socio-economic status, in contrast with more than 70% in the South West. Similarly, less than 10% of the children in North East and North West were from households in the highest wealth group, as against 32 and 47% in South South and South West, respectively.

Analysis by state shown in Figs. 15.11, 15.12 and 15.13 illustrates that while more children in the southern states escaped poverty over time, a higher proportion of those in the northern states were still trapped in the poor class. As of 2018, more than half of the children in Jigawa, Sokoto and Zamfara states, all in the North West, were from households in the lowest socio-economic status, in sharp contrast to Abia (South East) and Lagos (South West) with 54 and 76% of their children, respectively, in the highest socio-economic status. Results also reveal a more even spread of wealth in the southern states than in the northern states. The FCT (Abuja) in the North Central recorded the highest proportion of children (39%) in the highest wealth quintile amongst the northern states, a reflection of its socio-economic pull because of its status as the country’s seat of power. Similarly, Lagos being the commercial nerve-centre of Nigeria also trumped the rest of the southern states, and the country at large, with the highest proportion of children belonging to households in the highest wealth quintile.

4.5 Summary of Trends in Maternal Care

This section presents results on components of maternal care leading up to pregnancy, with focus on antenatal care visits, place of delivery and access to a professional birth attendant during delivery. Results on ANC attendance during pregnancy showed clear variations across geo-political zones and states. Findings by geo-political zones in Fig. 15.14 indicate that the South West with 84% in 2018 reported the highest proportion of children whose mothers attended ANC up to the recommended four visits during pregnancy, while the North West with 42% reported the lowest. Generally, there were reductions in the proportion of children born to maternal women who did not attend ANC during pregnancy throughout the study period. Nevertheless, more than 25% of the children in the northern zones still had mothers who did not attend ANC.

State results in Figs. 15.15, 15.16 and 15.17 underscore what was shown at the zonal levels with regards to improvement in the proportion of children born to women who received at least four antenatal cares. However, there still exist a high proportion of children whose mothers did not receive antenatal care, with Zamfara and Sokoto (in the North West) as high as 64 and 53%, respectively, in 2018. Osun state (South West) at 96% had the highest proportion of children whose mothers attended ANC at least four times, while Kebbi (North West) with 27% had the lowest.

Moving on to place of delivery. Results by geo-political zones shown in Fig. 15.18 suggest that a high proportion of the children were still delivered at home. It is evident that home deliveries expose maternal women and infants to higher risks of mortality and should be discouraged (Greenwell & Winner, 2014). The North West had the highest rates of home deliveries throughout the study period from 91 to 84%, while South East and South West with 17% had lowest proportions of home deliveries. While other geo-political zones reported more deliveries at the government health facilities, the South East reported more deliveries at the private facilities.

State results in Figs. 15.19, 15.20 and 15.21 further accentuate what was seen at the regional level. The 2018 NDHS results suggest that more than 80% of the children in the North West states were delivered at home. The highest proportion of home deliveries was Sokoto’s (North West) 92%, while Imo’s (South East) 5% was the lowest proportion of home deliveries in 2018. Amongst the South East states, Ebonyi had a marked high proportion of home deliveries. Remarkably, there is a growing demand for private health facilities, especially in the southern parts of the country, with Imo State (South East) reporting in 2018 that about three-quarters of its deliveries took place in private health facilities. Amongst the southern states, Bayelsa in the South South geo-political zone recorded a distinctively high percentage of home deliveries (76% in 2018). In retrospect, Bayelsa’s delivery result is also like its ANC result, where proportions of children whose mothers did not attend ANC during pregnancy at 36, 52, and 47% in 2008, 2013 and 2018, respectively, were the highest in the southern region.

Further results on level of maternal care available in the country are shown in Table 15.7. It indicates that less than one-fifth of the children in the North West were attended to by a professional birth attendant during their delivery, unlike 85% of those in the South East and South West who received such care during delivery. State results further highlight the trend seen at the regional level. In the 2018 NDHS result, Kebbi and Sokoto in the North West had less than 10% assisted deliveries in stark contrast with more than 95% in Abia (South East), Imo (South East) and Osun (South West). Again, as seen earlier in results with ANC attendance and place of delivery, Bayelsa state also consistently had the lowest proportions of children whose births where assisted by a professional birth attendant amongst the southern states.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

Using the three most recent datasets of the NDHS, this chapter explored spatial differences in under-five mortality, as well as trends within geo-political zones and states over more than a decade and compared them with key socio-economic factors associated with under- five mortality. The results confirmed that mortality risks during infancy (0–11 months) are higher than mortality risks in the childhood period (between 12 and 59 months). Findings also echo the lack of progress in improving child survival in Nigeria during the study period. Additional sub-national analysis showed wide-ranging between-zone and within-zone disparities in under-five mortality. While the percentage of under-five deaths declined steadily in the South East, South South and South West throughout the study period, the reverse was the case in the North Central, North East and North West from 2013 to 2018. Generally, the proportion of under-five deaths were lowest in the South West and highest in the North West. With regards to trends, there were distinct patterns between states. This was an important finding, indicating that the increase in under-five mortality at the national level from 2013 to 2018 is disproportionately due to the situation in the northern regions.

Results on the study variables indicate that the North West had the highest proportion of under- five children born to women with no formal education, with as high as 73% in 2018 in sharp contrast to 3% in the South East. Similarly, the northern regions had higher proportions of maternal women with no education, while the southern regions had higher proportions of maternal women with secondary or higher levels of educational attainment. Evidence shows that maternal education helps in controlling fertility, preventing early marriage and empowering women economically (Ezeh et al., 2015; Morakinyo & Fagbamigbe, 2017; Negera et al., 2013). Adebowale et al. (2012) added that, to a large extent, literacy cancels the effects of cultural and religious beliefs such as early marriage. As evident in the South West region, with a similar high proportion of Muslims to the north, the high level of female educational attainment reduces early marriage, unlike in the northern regions with lower female educational attainment and high child marriage. The practice of early marriage further limits women’s access to education and participation in economic activities (Adebowale et al., 2012).

The North East and North West also reported higher proportions of children in households in the lowest wealth quintile, as well as higher wealth inequality, an indication of higher poverty spread and concentration of wealth with a few individuals. In addition to this pattern, the northern regions also reported higher proportions of children born to mothers who did not receive antenatal care, those that were delivered at home and without professional assisted delivery. A high of 84% of the deliveries in North West from NDHS 2018 were at home, further exposing the mother and new-borns to birth complications and infections due to unhygienic environment and lack of professional care.

Studies have shown that poor maternal education is associated with poor ANC attendance, which also reduces the chances of hospital delivery and assisted delivery by a healthcare professional (Doctor et al., 2011; Ononokpono et al., 2014). These imply that the clear inequality in under-five mortality by state cannot be considered in isolation from the socio-economic development at the states. Fetuga et al. (2007) added that socio-economic factors are associated with poor utilisation of health services. While those of lower socio- economic status and those resident in the rural areas are most affected by this, those of higher socio-economic status can afford private health care even if it is expensive, further widening inequalities in under-five mortality. Information on access to health care, which covers antenatal care, hospital delivery and assisted delivery, helps in addressing gaps to health care access in Nigeria. Aday and Andersen (1974) in their framework on access to medical care stated that access to health care was an interrelation of variables from health policy objectives to customer satisfaction.

To this end, if policies and interventions are not designed and implemented to address sub- national variations in under-five mortality at the state level, then under-five mortality levels in Nigeria would most likely continue to be high. Socio-economic gaps in the composition of individuals, households and communities at the states that are creating these inequalities in early childhood mortality should be addressed, otherwise the inequalities will persist. More importantly, factors such as socio-economic status and access to quality maternal and child health care need to be critically addressed. Findings across states should create more conversation aimed at addressing observed spatial variations in under-five mortality across the country. While policymakers and programme implementers need to prioritize action in the north, they should also target broad socio-economic development across states.

References

Adamu, P. I., Okagbue, H. I., Akinwumi, I., & Idowu, C. (2021). Trends of non-communicable diseases and public health concerns of the people of northeastern Nigeria amidst the Boko Haram insurgency. Journal of Public Health, 29(3), 553–561.

Aday, L. A., & Andersen, R. (1974). A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Services Research, 9(3), 208–220.

Adebowale, A. S., Yusuf, B. O., & Fagbamigbe, A. F. (2012). Survival probability and predictors for woman experience childhood death in Nigeria: “Analysis of north–south differentials”. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 1–12.

Adebowale, S. A., Morakinyo, O. M., & Ana, G. R. (2017). Housing materials as predictors of under- five mortality in Nigeria: Evidence from 2013 demographic and health survey. BMC Pediatrics, 17(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0742-3

Adedini, S. A. (2013). Contextual Determinants of Infant and Child Mortality in Nigeria.

Adedini, S. A. (2014). Neighbourhood characteristics and under-five mortality in Nigeria. African Population Studies, 27(2), 273–287.

Adedini, S. A., Odimegwu, C., Imasiku, E. N., & Ononokpono, D. N. (2015a). Ethnic differentials in under-five mortality in Nigeria. Ethnicity health Place, 20(2), 145–162.

Adedini, S. A., Odimegwu, C., Imasiku, E. N., Ononokpono, D. N., & Ibisomi, L. (2015b). Regional variations in infant and child mortality in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Biosocial Science, 47(2), 165–187.

Adedokun, S. T., Uthman, O. A., Adekanmbi, V. T., & Wiysonge, C. S. (2017). Incomplete childhood immunization in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis of individual and contextual factors. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4137-7

Ager, A. K., Lembani, M., Mohammed, A., Ashir, G. M., Abdulwahab, A., de Pinho, H., et al. (2015). Health service resilience in Yobe state, Nigeria in the context of the Boko Haram insurgency: A systems dynamics analysis using group model building. Conflict and Health, 9(1), 1–14.

Ahmed, H. (2007). Effects of poverty on child health and paediatric practice in Nigeria: An overview. Annals of African Medicine, 6(4), 142–156. https://doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.55705

Akinyemi, J. O., Bamgboye, E. A., & Ayeni, O. J. B. p. (2015). Trends in neonatal mortality in Nigeria and effects of bio-demographic and maternal characteristics. 15(1), 36.

Amoroso, C. L., Nisingizwe, M. P., Rouleau, D., Thomson, D. R., Kagabo, D. M., Bucyana, T., et al. (2018). Next wave of interventions to reduce under-five mortality in Rwanda: A cross-sectional analysis of demographic and health survey data. BMC Pediatrics, 18(1), 27.

Antai, D. (2011). Regional inequalities in under-5 mortality in Nigeria: a population-based analysis of individual-and community-level determinants. Population Health Metrics, 9(1), 6.

Ayoade, M. A. (2020). Trends and temporal patterns of infant mortality in Nigeria. GeoJournal, 1–14.

Blackstone, S. R., Nwaozuru, U., & Iwelunmor, J. (2017). An examination of the maternal social determinants influencing under-5 mortality in Nigeria: Evidence from the 2013 Nigeria Demographic Health Survey. Global Public Health, 12(6), 744–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1211166

Bloom, D., Canning, D., & Sevilla, J. (2003). The demographic dividend: A new perspective on the economic consequences of population change. Population matters: Rand Corporation.

Doctor, H. V., Findley, S. E., Bairagi, R., & Dahiru, T. (2011). Northern Nigeria maternal, newborn and child health programme: Selected analyses from population-based baseline survey. The Open Demography Journal, 4(1).

Dunn, G. (2018). The impact of the Boko Haram insurgency in Northeast Nigeria on childhood wasting: A double-difference study. Conflict and Health, 12(1), 1–12.

Ekwochi, U., Ndu, I. K., Osuorah, C. D., Amadi, O. F., Okeke, I. B., Obuoha, E., et al. (2015). Knowledge of danger signs in newborns and health seeking practices of mothers and care givers in Enugu state, South-East Nigeria. Italian journal of pediatrics, 41(1), 1–7.

Ettarh, R., & Kimani, J. J. R. (2012). Determinants of under-five mortality in rural and urban Kenya. Rural and Remote Health, 12(1).

Ezeh, A., Oyebode, O., Satterthwaite, D., Chen, Y., Ndugwa, R., Sartori, J., et al. (2017). The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. The Lancet, 389(10068), 547–558.

Ezeh, O. K., Agho, K. E., Dibley, M. J., Hall, J. J., & Page, A. N. (2015). Risk factors for postneonatal, infant, child and under-5 mortality in Nigeria: a pooled cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open, 5(3), e006779. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006779

Fetuga, B., Ogunlesi, T., Adekanmbi, F., Olanrewaju, D., & Olowu, A. (2007). Comparative analyses of childhood deaths in Sagamu, Nigeria: implications for the fourth MDG. South African Journal of Child Health, 1(3), 106–111.

Fotso, J. (2006). Child health inequities in developing countries: differences across urban and rural areas. International Journal for Equity in Health, 5(1), 9.

Greenwell, K. F., & Winner, M. (2014). Infant Survival Outcomes in Guinea in Light of Improved Maternal and Child Care: Further Analysis of the 2005 and 2012 Demographic and Health Surveys. DHS Further Analysis Reports No. 96. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF International. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FA96/FA96.pdf

Hong, R., Banta, J., & Betancourt, J. A. (2006). Relationship between household wealth inequality and chronic childhood under-nutrition in Bangladesh. International Journal for Equity in Health, 5(1), 15.

Kayode, G. A., Adekanmbi, V. T., & Uthman, O. A. (2012). Risk factors and a predictive model for under-five mortality in Nigeria: Evidence from Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-12-10

Koffi, A. K., Kalter, H. D., Loveth, E. N., Quinley, J., Monehin, J., & Black, R. E. (2017). Beyond causes of death: The social determinants of mortality among children aged 1–59 months in Nigeria from 2009 to 2013. PLoS One, 12(5), e0177025. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177025

Lilford, R. J., Oyebode, O., Satterthwaite, D., Melendez-Torres, G., Chen, Y.-F., Mberu, B., et al. (2017). Improving the health and welfare of people who live in slums. The Lancet, 389(10068), 559–570.

Morakinyo, O. M., & Fagbamigbe, A. F. (2017). Neonatal, infant and under-five mortalities in Nigeria: An examination of trends and drivers (2003–2013). PLoS One, 12(8), e0182990. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182990

National Population Commission (NPC) Nigeria, & ICF. (2019). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018 key indicators report. Abuja, Nigeria and Rockville, Maryland, USA. Retrieved from http://dhsprogram.com/

National Population Commission (NPC) Nigeria, & ICF International. (2004). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA. Retrieved from http://dhsprogram.com/.

National Population Commission (NPC) Nigeria, & ICF International. (2009). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA. Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR222/FR222.pdf

National Population Commission (NPC) Nigeria, & ICF International. (2014). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA. Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR293/FR293.pdf

National Population Commission (NPC) Nigeria, & ICF International. (2019). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. NPC and ICF. Retrieved from http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR359/FR359.pdf

NBS. (2010). National poverty rates for Nigeria: 2003–04 (revised) and 2009–10 (Abridged report). Retrieved from http://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/

NBS. (2018). Snapshot of inequality in Nigeria (2004, 2013, 2016). Retrieved from http://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/

Negera, A., Abelti, G., Bogale, T., Gebreselassie, T., & Pearson, R. (2013). An analysis of the trends, differentials and key proximate determinants of infant and under-five mortality in Ethiopia. ICF International.

Ogbuoji, O., & Yamey, G. (2019). How many child deaths can be averted in Nigeria? Assessing state- level prospects of achieving 2030 sustainable development goals for neonatal and under-five mortality. Gates Open Res, 3, 1460. https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.12928.1

Ojewumi, T. K., & Ojewumi, J. S. (2012). Trends in infant and child mortality in Nigeria: A wake-up call assessment for intervention towards achieving the 2015 MDGS. Science Journal Publication, (2).

Olorunsaiye, C. Z., & Degge, H. (2016). Variations in the uptake of routine immunization in Nigeria: Examining determinants of inequitable access. Global Health Communication, 2(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/23762004.2016.1206780

Ononokpono, D. N., Odimegwu, C. O., Imasiku, E. N., & Adedini, S. A. (2014). Does it really matter where women live? A multilevel analysis of the determinants of postnatal care in Nigeria. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(4), 950–959.

Preston, S. H. (2007). The changing relation between mortality and level of economic development. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(3), 484–490.

Rosling, H. (Producer). (2006). The best stats you've ever seen. TED talk. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_the_best_stats_you_ve_ever_seen?utm_campaig n=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare.

Rutherford, M. E., Mulholland, K., & Hill, P. C. (2010). How access to health care relates to under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 15(5), 508–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02497.x

Rutstein, S. O., Ayad, M., Ren, R., & Hong, R. (2009). Changing health conditions and the decline of infant and child mortality in Benin.

Sanders, D., & Carver, R. (1985). The struggle for health: medicine and the politics of underdevelopment. The struggle for health: Medicine and the politics of underdevelopment.

Sastry, N. (1996). Community characteristics, individual and household attributes, and child survival in Brazil. Demography, 33(2), 211–229.

UN-DESA. (2019). World population prospects 2019: Highlights. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-2019- highlights.html

UN, I. (2019). Child mortality estimates. Retrieved from https://childmortality.org/

UNICEF. (2018). Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. UN-inter Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation website: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Child-Mortality- Report-2018.pdf: UN-inter Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation.

United Nations. (2017). World Mortality Report, 2015.

Van Malderen, C., Amouzou, A., Barros, A. J., Masquelier, B., Van Oyen, H., & Speybroeck, N. (2019). Socioeconomic factors contributing to under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: a decomposition analysis. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–19.

Wang, H., Liddell, C. A., Coates, M. M., Mooney, M. D., Levitz, C. E., Schumacher, A. E., et al. (2014). Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the. Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, 384(9947), 957–979.

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. E. (2006). Income inequality and population health: a review and explanation of the evidence. Social Science & Medicine, 62(7), 1768–1784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.036

Wilmoth, J. R. (2003). Mortality decline. In P. Demeny & G. McNicoll (Eds.), Encyclopedia of population (Vol. 2, pp. 654–662). Macmillan Reference.

World Bank (2019). GDP per capita (current US$)- Nigeria. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?contextual=aggregate&end=2018&locations=NG&start=1960&view=chart

Yaya, S., Ekholuenetale, M., Tudeme, G., Vaibhav, S., Bishwajit, G., & Kadio, B. (2017). Prevalence and determinants of childhood mortality in Nigeria. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 485. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4420-7

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Umesi, L.U. (2023). The Nexus Between Development and Early Childhood Mortality in Nigeria. In: Adewoyin, Y. (eds) Health and Medical Geography in Africa. Global Perspectives on Health Geography. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41268-4_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41268-4_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-41267-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-41268-4

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)