Abstract

Surveys of college graduates and educational research on the college experience point to the important role faculty play as mentors to students—helping them to find their way into and through the institution and to consider postgraduate choices. In conversation with 54 students from seven institutions in the Consortium of Innovative Environments in Learning (Bennington, Fairhaven, Hampshire, Marlboro, New College Alabama, New College Florida, and SOIS at RIT) over two years, we learned a good deal about how our students understand the impact of the mentoring they received. We saw how mentoring was influenced by program and institution structure as well as by formal and informal opportunities for connections between students and faculty. In this chapter, I focus on the nature of a mentoring role that is purposely aimed at developing students’ intellectual lives and academic choices and explore the institutional structures that support it. I end with suggestions for improving faculty mentorship of undergraduates at any institution.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Many of the institutions in the Consortium of Innovative Environments in Learning (CIEL) were designed, as was Hampshire College, with the expressed intention of educating individuals to be creative and independent thinkers who find their own purpose (Patterson & Longsworth, 1966). Central ideas for these institutions include (a) individualization of a student’s educational path; (b) the application of knowledge through projects done under the aegis of a faculty advisor or a committee; and (c) increasing social justice through active engagement. For each of these shared components and many other curricular issues and goals for students that are peculiar to each institution, faculty mentorship plays a major role in student success.

We often say that student work is fostered through close “advising” by faculty, staff, and peers. The conversations we had with students in completing this project challenge us to revise our understanding of the faculty role from that of “advisor” to “mentor,” as the advising role at many institutions is transactional. That is, advisors give approval for course registration, study abroad, field study, and so on. A mentor engages with the students’ questions and individual goals, learning about their intellectual life. The conversations can lead not only to discussions of different possible paths through the institution, but also to the ways one can create a life post-college. That is not to say that mentors simply point to courses and other experiences that support students’ thinking—they challenge students’ thinking and ask them to stretch in new directions. Understanding the role of mentor as distinct from advisor can highlight the components of this aspect of our work and lead to the strengthening of mentorship.

I want to be clear that I am not talking about the romanticized view of a single mentor who takes a student under their wing. As you’ll see, our students have rich mentoring networks. Yet, faculty play unique roles that support students in planning their programs of study and making meaning of their experiences in and out of the classroom. Mentorship is an important ingredient in developing integrative thinking.

As with any teaching-focused institution, the models of progressive education featured in this book all require and encourage faculty mentorship of students. But just how mentorship best benefits students and can be developed effectively in an institution requires understanding more about the student experience in that institution. In particular, what kinds of interactions, programmatic features, and institutional practices bring about the best features of faculty mentorship? And how might lessons from a select few CIEL institutions considered here provide deeper understandings of the potential for mentorship in a broader range of institutions?

The main thrust of this chapter is on the student experience of mentoring in the students’ own words, but I start briefly with my own experience as a faculty member mentoring students at Hampshire College. Then, I share the reflections of one Hampshire student as they moved through their four years considering the role one faculty member played in their academic career. Then I highlight other examples of how mentoring at CIEL institutions has provided students with (a) emotional and psychosocial support; (b) direct assistance with career or academic development; and (c) role modeling. Finally, I explore the institutional structures that appear to foster mentoring relationships, and leave you with ideas that, I hope, can enrich faculty mentoring of students at your institution.

Faculty Experience of Mentoring

My favorite part of my job is mentoring undergraduates. My early experiences as a teacher and advisor often put me in a position where the expectation was that I would dispense information and advice. Of course, I often do just that. But as I work with students in and out of the classroom, I have learned to listen as much as I speak, to tease out their ideas, to challenge them, and to see where their thinking goes. I love listening as their ideas unfold. And I find it rewarding to guide them as they ask their own questions and devise methods for gaining purchase on them. And I marvel at the portfolios of work they produce and the sophistication they show in understanding their own strengths and challenges. I believe the growth that results from the mentoring relationship is not unidirectional—I learn a great deal from my students. I’ve developed new courses as a result of the questions students have brought to me. Mentoring keeps me learning; it has made me a better teacher and advisor—and likely, a better person.

Student Experience of Mentorship

More important than the faculty experience of mentorship is the ways it supports student growth. McKinsey (2016) makes the case that mentorship entails helping an individual move from one stage of life to another, work that clearly goes beyond the role of a course instructor or advisor. This idea is derived in part from the developmental literature—from our understanding of what it takes to transition to college, move through it, and then consider the next steps after graduation. She talks about “mentoring in, mentoring through, and mentoring onward.” At each of these phases in a student’s college career, our actions can support them as they undergo enormous psychosocial, intellectual, and identity changes.

By way of demonstrating the ways mentoring relationships might look over time, I share the views of one Hampshire College student that was interviewed at the end of their fourth year. They described some of the important roles their faculty mentor had filled. She was instrumental in mentoring them in, through, and onward (McKinsey, 2016). Their relationship began as their professor, the instructor for their first-year seminar, oriented them to the college, and helped them feel as though they belonged.

In order to make sense of the student’s experience, it is necessary to understand some Hampshire-specific curricular elements. Hampshire students move through three Divisions in their four years at the College. Division I is the first-year program, and a time of exploration across the disciplines. Division II is the middle two years in which a student works with a committee of two faculty to design and complete an individualized concentration that culminates in a reflective ePortfolio. Division III is the final year in which a student is mentored by a committee of two faculty to complete a robust full-year project demonstrating their ability to answer complex problems and further develop skills in their area of concentration.

The student remarked:

She is just an incredibly caring person, and so she would care for her students as individuals … and that means a lot to me. [She] cares about her students in a holistic way which is similar to a parental relationship.

Of course, mentorship was not just about a sense of belonging but also of extending students’ understanding of their academics. This student came to Hampshire College with an idea that they were interested in media studies, but without much depth of understanding of the field or what types of courses and experiences would support their learning, and certainly without fully understanding how the Hampshire curriculum works:

I came into college thinking I knew what I wanted to study, and she helped me understand what that really was… It made me think about what I was doing here. I think that I thought [media studies] was more like film studies… But what media studies really is is like a study of culture and a study of culture’s effect on society—media’s effect on society.

Not only did she support their intellectual questions, she shared information and resources available at the college. As this student moved into their second year, in which they organize a committee of two faculty to guide them in the development of their educational plan for their individualized concentration, their mentor got to know them, their interests and goals. She supported them in reaching their academic goals and finding the resources and opportunities that mattered:

I was writing academic papers different than I’d ever written before. I mean, she consistently connected me to library research help and writing help. And she always lets me know about grants and places that I can submit my work. She has always encouraged me to go to—I don’t know if ‘mixers’ is the right word but—events where people are talking about their Division II’s or talking about Division III’s, so it’s creating like a community of scholars.

Their mentor also brought her own students together to build their intellectual communities:

She’s had several—it’s kind of like group advising, but it’s more like she’s had social gathering for all of her advisees. So, we’re going to a barbecue at her house with a lot of other students. It let me get to know, first of all, more of the people that she is working with, but also her family. So I got to meet a lot of people.

Throughout their work together, the student still felt seen as an individual:

I think that she’s never let me get away with anything…she has made it clear again and again that nobody’s going to take my work seriously if I don’t, or nobody should, at least. I remember early in my Division III, there was a moment where she was saying how a piece of my work affected her and what it made her think of… which made me think about my work in a different way. And especially as a media studies student, it’s like you have to be thinking about how the audience is going to react to the thing that you put forth.

As they completed their studies, their mentor helped mentor them onward: “And then with postgraduate planning, [she] again has been really helpful.”

All in all, as the student reflected on the importance of this relationship, they considered the way that the structure of Hampshire’s curriculum supported the development of a mentoring relationship:

I mean, I think it’s supported by like, allowing me to choose my committee … even though I ended up being like a media studies student and a theater student—I could still have an institutional relationship with this faculty member, even as my work diverged from hers… My Division III is documentary theater and so it involves interviews and a lot of the stuff that I’ve learned from media studies. It addresses concepts of mass culture and how people decode media but it’s not straight media studies, but it is applied. The classes I took with her did a good job of teaching me the methodologies I needed.

At Hampshire, it’s all about reflection—from how you talk about the assignments that you do, to your evaluations, to your retrospectives, to your portfolio, it’s all about—it’s not just about moving forward. It’s about moving forward while understanding what you did. You can’t just move forward blindly.

This student’s mentor not only helped them understand the field, she helped them learn an important methodology that was useful in a more interdisciplinary piece of work. And she helped the student make sense of the intersections by supporting their reflection and meaning making. But the relationship did not simply happen by chance. The institution created the structures that ensure mentoring relationships happen for all students.

Why Focus on Faculty Mentorship?

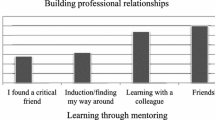

From 2017 to 2019, we spoke with 54 students in their final semester before graduating from one of seven CIEL institutions about their experiences of mentorship. In one set of interviews, we began conversations by asking students to draw a mentoring map. We gave them a paper divided into four quadrants, each one representing a different potential area of need: (1) Understanding/Navigating your educational path, (2) Academic skills and knowledge, (3) Wellness and academic/social balance, and (4) Postgraduate planning. We first asked each student to identify the people who had supported them in each of these areas; then we asked them to examine all four quadrants of their map and to identify their primary mentor.

Two striking results emerged from these conversations. First, students had robust networks of mentors, or what Higgins and Thomas (2001) call “mentoring constellations.” Rarely was there an empty quadrant. Figure 1, for example, shows a typical map. Students could identify so many supports because we have created institutions that are highly relational, rich in both “planned” and “natural” mentoring. McKinsey (2016) makes a distinction between planned mentoring, where mentors are recruited and assigned to students, and natural mentoring, which is more spontaneous and occurs organically.

The networks that these students detailed are exactly what Felten and Lambert (2020) describe as the important sets of connections that drive student success in college, supporting students’ academic and personal growth, as well as graduate school and career planning. Some of the connections were ongoing, while others were more fleeting, but occurred at important moments, such as academic decision points, moments of needs in a project, or times of personal strife. Some were with peers or near peers, and others with staff or faculty. Their effects are likely long-lived and some of these relationships will surely endure post-graduation.

The second interesting point that came out of the mapping exercise is that although students identified a number of individuals as their mentors in each quadrant, when asked to identify their primary mentor, nearly all identified an important faculty member rather than their peers or staff.

In a 2014 analysis of the Gallup-Purdue study, Ray and Marken report that far more important than any other aspect of an institution, connection with faculty mattered. Those individuals who had a professor who got them excited about learning, cared about them as a person, and encouraged them to pursue their goals and dreams were more than twice as likely to be thriving in their careers and in all aspects of their lives as those who did not have such faculty support. Working on a sustained project and having an internship were also highly impactful experiences. But few students across the country had the combination of all these components.

What many of our progressive institutions do is to ensure highly relational faculty mentorship coupled with projects designed to address students’ own questions or individualized educational planning to support their growth on their own goals—what Ray and Marken (2014) call a winning combination. What we can surmise is that what students do and how they do it is critically important. It is incumbent, then, on those of us in higher education to consider how we can foster these high-quality experiences in our institutions, and to do so in an equitable way. These experiences should be built into the institution for all students to experience, not just the honors students who more regularly have access to research experiences with faculty (Mintz, 2021).

If mentors are not provided, we are depending on students’ abilities to find a mentor. Considering the research by Lareau on unequal childhoods, we might imagine that students who are more likely to develop meaningful relationships with faculty are middle-class students with college-educated parents. These are students who have experienced the kind of concerted parenting that taught them that they are entitled to ask for what they need and that gave them the skills to do just that. The Strada-Gallup data support this supposition. Seventy-two percent of white students cited a professor as a mentor in college, compared with only 47% of students from traditionally underrepresented racial groups. And, first-generation students were also less likely than students with a college-educated parent to have had a professor as a mentor. Some research also points to gender differences in student reports of having a relationship with a mentor, with female students less likely to report being mentored than male students (Johnson, 2007). Without an institution-wide program that ensures mentorship for all students, we are likely widening the inequities that plague our society.

Many colleges have developed, or are in the process of developing, peer mentorship programs. These are important in adding to a student’s mentorship network or constellation. But they do not replace a faculty mentor. In the 2018 Strada-Gallup Alumni Survey, 64% of respondents say their mentor is a faculty member. But only about a third of students agreed that they had a mentor who encouraged them to pursue their own goals. Despite years of understanding the importance of faculty mentorship, institutions struggle with the costs and pressures that make robust faculty mentorship a relative rarity. How do we build such relationships in a sustainable way? It will take some work at most institutions to consider just how to build faculty mentoring into the institutional structure. The faculty-to-student ratio can mitigate against mentoring (Johnson, 2007).

What Other CIEL Students Had to Say About Their Faculty Mentors

Faculty mentoring matters across all institution types. What can we learn by listening to student voices at progressive institutions? First, we can see examples of the ways students discussed the supports they received. Our students discussed supports along three categories of mentor functions that Jacobi (1991) identified: (1) emotional and psychosocial support, (2) direct assistance with career or academic development, and (3) role modeling. Second, by looking at the contexts in which students received these supports, we can understand the institutional structures and practices that led to the development of these mentoring relationships. Our institutions are deliberate in how we structure our curriculums to necessitate faculty mentorship of students and create relational cultures.

Emotional and Psychosocial Support

Years of research on belonging at college makes clear that a sense of belonging is crucial to students’ adjustment to college, retention, and academic success (Strayhorn, 2012; Felten & Lambert, 2020; Bowen, 2021). As we have seen, no one person is responsible for a student’s sense of belonging; it is improved by having broad networks of connection (Felten & Lambert, 2020; Packard, Walsh & Seidenberg, 2004). Yet there is at least indirect evidence that college faculty have a profound effect on a student’s psychosocial well-being through a mentoring relationship (Jacobi, 1991; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1977).

When first arriving at college, students need a sense of acceptance or welcoming that encourages their participation. McKinsey (2016) characterizes this phase of a mentoring relationship as “mentoring in.” It is a component of orientation to a college or to a discipline or activity. Our students note aspects of their relationships with faculty that led them to feel accepted, encouraged, and supported. One student said:

[I]t’s a lot harder for a young person who’s trying to figure out why they’re even doing this or what’s driving them to do this, and it’s scary and there’s all this self-doubt and just trying to figure it out…There are thousands or millions of other college students who are just alone in that process and I’ve had all this help and all this encouragement from [my mentor]. I have grown probably so much more than I would have anywhere else.

Not only did students’ mentors become a part of a student’s network of support, they also often took on almost a surrogate parentship as students forged new and important relationships in their first years at college. For example, this student said:

My first year, he was my adviser… As freshman, so you’re coming, you’re nervous, but you feel like, I got this or maybe I don’t. And taking his class and having him as my mentor was—I feel like set me on—put me on the right path because I could easily [have] messed up my first year, because I had so much respect for him and he believes so much in me and what I was doing and … he would always encourage me. It was like there was this watching eye for me and no matter what, they got me. I got that feeling from my first year. So, I felt like he was a parent in college. I didn’t want to disappoint him, so I would stay on track.

CIEL students often noted that their faculty mentors were not only people with whom to discuss academic interests but that they also discussed their emotional life—perhaps not in great detail about the content, but certainly about how they were doing in general and how their emotions affected their work. In that way, faculty were invited in to be part of the support system that allowed students to practice the skills associated with resilience. Such a sense of care gave students the safety to take risks, and develop strategies for decision-making and personal growth, including new ways to manage their emotions. One student said:

I just feel like every time I have a meaningful relationship or a meaningful connection with [my mentor] I feel like incredibly rewarded and it makes me look at everything more optimistically and even more practically and makes—makes me slowly, but surely, make wiser decisions about what I’m doing and what I want to do and who I want to surround myself with.

Another student related:

I think just like having someone that I feel so supported by in the decisions that I’m making for myself at college. I feel like [having] someone in the back pocket cheering me on has just really allowed me to take more risks with what I do and feel more confident about what I’m doing and being able to do lots of things.

And a third student recounted:

He’s also encouraged me to be a little less critical of myself, kind of get out of my own way so that I can be doing my best work without overwhelming myself, which I think is also really important. I tend to be a perfectionist student, and so I need that voice sometimes to be like, “It’s okay. You’re doing it. Don’t get too worked up over it.”

These three students give us a glimpse into how mentoring relationships led to important exploration and growth—epitomizing what Bowen (2021) describes as the connection between relationship and resilience. After all, resilience not only requires one to sit through the discomfort of failure, it requires supportive feedback. Faculty can let students know that we often learn more through our mistakes than by getting things right the first time. And we can offer the support and gentle correction that increase resilience.

Our students credited their mentors with taking them seriously and treating them as the adults they are:

[My tendency to take a leadership role] grew and thrives here and that’s probably because here people take me seriously—like there are adults who take me seriously and I don’t feel like I’m treated like an undergrad college student. I feel like I’m treated like someone who wants to be engaged and around.

Another said:

I didn’t know that I will have people who will have my back, not just when I’m in front of them but they talk about how to evolve me with each other. So that really meant a lot because I didn’t know what to expect at all. It made me feel like I’m important, my work is important. Because I feel insecure about my writing, about speaking out loud because of accent. And he’s like, “What? You shouldn’t be because—” And not just saying it but meaning it—“you are smart. You are important. You are here. If you were supposed to know everything, you wouldn’t have been here. You’re here for a reason and to learn. That you must do. You must not stop yourself because you feel like you don’t know something.”

And another student’s response not only highlights the importance of the emotional support they received, but it also exemplifies the concomitant growth in metacognitive skills that they developed. This student learned a critical thinking process from their mentor that they were able to apply elsewhere:

I think just like I have learned a lot more about trusting my own gut and things, like I said, a lot of what [my mentor] has done for me is lots of listening and me working it out and then validating how I feel. And so, I feel like I’ve come to trust my own initial judgments more. I don’t feel like I need to go to her as often and say, “I have no idea what to do about this’ and have me talk it out. I’ve learned to be like: ‘I’ve worked out in situations like this before. I’ve thought about things critically in this way and kind of trusting myself.”

I have heard faculty say that they are not equipped to support students emotionally, that they are not therapists. We can see here that one need not be a “therapist” to show caring, to listen, to reassure, and to point out the strengths we see in our students. As faculty mentors, then, we can’t shy away from this important role. It makes an enormous difference in students’ personal and academic growth.

Direct Assistance with Career or Academic Development

Perhaps this is the role we most identify with a mentor and certainly our students had much to say about the importance of faculty in guiding their learning, their academic path and their skill development, connecting them to internships and campus resources, helping them reflect and make meaning of their work, and affecting their ideas about possible futures.

Effects on learning:

Students spoke of the importance of specific feedback on their work and the way this drove them forward. Here is one example that is typical of faculty mentors’ effects on learning:

I think I’m a lot more confident in my work because I have somebody with their full attention on it telling me that it’s good. Or that it’s not good or this or that. Or telling me what I can improve on. Whereas, if I were in a bigger university, I’d have feedback but it wouldn’t be as detailed or as well-informed.

And another student said:

I’m a completely different person, that’s for sure. I’ve grown into someone totally different. My professors have been really responsible for that, my friends, not so much. My friends were just kind of my comfort, but my professors were the ones who were there to teach the classes, were there to help me understand the classes.

Academic paths:

Faculty often queried students about their interests and reminded them of things they had said or done in the past. They acted as sounding boards and offered their perspectives on student work:

She just has really challenged me to think about my academics in a really interdisciplinary way which I did not really do when I came to Hampshire. And having someone consistently be so connected to my academics and career, she’s been helping me with internships and summer things and things like that. So, someone closely connected to that for many years in a row has been so helpful… [She’ll say]: ‘Well, you did this second year,’ or ‘You were thinking about this this semester,’ or ‘Bring in this thing from your internship,’ and just having someone that knows my academics so well and knows the path, especially I feel like my time at Hampshire, my academics have really gone on a very deliberate path thing from this to this to this to this.

Yeah. Absolutely. I think that it’s helped me to grow as a person, and I’ve done things—I wouldn’t have come into New College thinking I would start a farm. I wasn’t going to do any of that. But talking to people about sustainability, for example. That’s helped me. I mean, I was kind of interested. I dabbled in it before, I had the Green Club in high school, but wasn’t going to do farming, wasn’t interested in food or whatever beyond that. And so, all these conversations and just talking about that has given me a different direction that’s been relatively influential, at least in the past year or so.

In helping set academic paths, faculty helped shape students’ ideas about what was possible for them. Their feedback and encouragement led students to consider possible coursework and career paths they had not considered before.

Possible futures:

I’m a first-generation student, and so getting a bachelor’s is a huge thing. I didn’t really have anyone pointing me and being like, ‘Oh, you should continue on to a master’s program’ until I was here and I was working with faculty who had gone through it and who assured me like, ‘You can do this. We believe in you.’ And just having that type of support here where I couldn’t get it at home is amazing, and it’s changed so much for me.

He told me like, “I see that you like teaching and someday I feel like you’re going to be a good teacher.” And I’ve heard that before but affirming that from a professor who teaches, I was sort of like ‘I don’t believe it.’ But later in my college career, I started taking interest in teaching, [they were] seeing something that I didn’t see before.

Academic and professional mentoring was not only accomplished through helping students consider possible future selves and encouraging them to keep going with their studies, faculty also introduced students to scholarly journals, associations, and authentic life experiences related to their academics.

He’s had me join the American Chemical Society … I’m going to go do a presentation at their conference in a couple of weeks but it also has career resources and whatnot. I worked with—or at least under his guidance … He’s had me instruct others on methodologies that I’ve developed for the project under the guidance.

But [my mentor] has been wonderful to work with. He’s really eager to share any and all knowledge he has in both the course setting but also continued in the personal struggles of being an artist or publishing tips or just other things that kind of come with the trade so that when I’m back out in the real world without the academic setting, I have a really good basis on what I’m doing with my chosen field of study.

Internships, resources, and other opportunities:

[T]here’s been a lot of pieces that are working with the community and working with youth outside of Hampshire and especially in summers. She has helped me connect with [community engagement staff] to put some of those internships together and was the first person to tell me about the different types of funding that I could get for my summer projects which allowed me to do the things that I’ve done. The last two summers, I’ve gotten grants to cover my summer work with youth. So having someone to be able to connect me with those types of resources.

[W]ell I think I was lucky to have a plethora of mentors in so many different ways and even when I was studying abroad, I met, I had so many professors in that experience who were from the place I was studying and weren’t Hampshire related that were extremely impactful. So, I think, and I was encouraged by Hampshire professors to take that experience and to kind of take that risk and so I think that having been pushed to do that and then having met those people, I kind of attribute that to my Hampshire professors in a lot of ways.

I’m currently doing Word Fest, and he told me to apply to that… It’s a play writing workshop for playwright scholars, students from the five colleges, and they each submit 10 minutes of their play. When they get accepted, they present, they get to present the play.

Reflection and meaning making:

It’s kind of helped me make sense of how things fit when I don’t see them fit, even like during my pass meeting, I was like: ‘Well, I kind of went from this to this and like this. So, none of it connects.’ She has kind of been someone that has challenged me to think about, well, all of it connects in this way. It’s helped me think about my academics as a whole and how I can bring everything that I’ve learned into one thing.

Faculty as Role Models

At times, we as faculty might not realize the impact that we have on students by sharing the stories of our own paths and by openly demonstrating our love of learning, our passions for our chosen fields, or sharing our own scholarship. Listening to student voices about the importance of working in the company of devoted faculty highlights our function as role models. Here is what three students had to say:

I feel nervous about the plan to take time off [before grad school] and a little bit unsure of what I’m doing but I also think that that’s really normal. I feel really excited for graduate school, I feel like I don’t wanna rush it … but with getting my MFA which is what I want to do, um, it feels like something I really don’t want to rush. My committee were really supportive of this. They both told me about what they did before graduate school. It was really—really reassuring that they did a few things before grad school. I didn’t realize.

I would say that they have been nothing but helpful. I mean like truly … they have done nothing but—how do I put it—like encouraged my commitment to the concept of education. And I mean, not just through the coursework they asked us to do, but also through them as role models, as like elementary as that might sound.

Yeah. He does inspire me to do my best work. [It’s] his free spirit. I don’t know. It’s really weird. Since the first day, I was just—he’s very passionate about what he does, about his work. I’ve seen his performance. I’ve seen him teach and how he responds to students.

Students might be inspired and impressed by faculty and their accomplishments, but that is not all there is to being a role model. There is a component of illuminating the path and making it clear that this is a path that is open to them as well. It is not an exclusive club, but a viable option. Students were heartened by the welcoming nature of their role models:

It’s had a tremendous impact on my life and being guided in a way I should get to where I’m trying to go … And I see that, and I have a chance to be mentored by this person who actually wants to invest time in me and not just saying ‘go research it on your own’ but telling me how you got there. And my path may not be the same as yours, but you’re still giving me resources and tools to say ‘this is how I got here, this is what I suggest.’ It’s been good.

I think absolutely it inspires me to do my best work just because as you walk up and down the halls of New College you have published works by the faculty in frames down the hallway but then their doors are also open and they are warm, friendly, and helpful. It’s an interesting dynamic of being around impressive people and then very inspiring faculty but also people who bring you in and want you to be successful as well.

It is helpful in trying to improve one’s own mentoring capacity to better understand these functions of mentors. We can recognize our own relationships with students and practice the attributes of those who support students across their academic and career paths and their social/emotional lives, seeing ourselves as role models who can help students along paths that we see clearly, but might be invisible to a novice. If we want such experiences for all students, we must think institutionally and not solely about our own practices.

Institutional Structures That Supported Mentoring

Students do not necessarily come to college knowing that a mentor is important or knowing how to find one (Lambert, 2018). That is one of many learned behaviors that lead to success at college. If our institutional structures do not support the development of mentoring relationships for all students, we are creating a hit-or-miss situation where one’s prior experiences and current luck affect future resources and outcomes.

From our discussions with students, it became clear that the nature of mentoring was connected to program and institution structure as well as requirements and opportunities. There are differences in how mentorships are set up on our campuses with different opportunities for contact and for different degrees of both informal and formal mentoring. Just what are the institutional structures that support mentoring? From our vantage points at CIEL institutions, these can be: (a) curricular structures and the practices that grow up around them, (b) physical structures, and (c) the structure of the faculty.

Curricular Structure

The type of work that faculty do with students varies by institution. In describing mentorship, students often noted how their work with faculty affected them as they developed their self-designed concentrations, ePortfolios, and capstone projects. These were inflection points in the curriculum that seem to support goal-setting, reflection, and the development of inquiry skills that required mentorship. Here is what students had to say about their experiences:

Self-designed programs of study:

“I think one thing that definitely helps is just the structure of having committees of choosing who you want to work with and again getting all of these combinations of people together…So having the ability to really sit down and think about who you want to work with and who would be beneficial to your project and who you think can offer you the best advice is certainly helpful.”

“…you get paired up with an adviser—who really becomes your point of contact for your educational journey…Fairhaven has created that culture by having an adviser who is your single point of contact who really coaches you and mentors you through your educational journey.”

ePortfolios

“Until I started to build my ePortfolio, I had no idea that there were themes that kept—that kind of drove my work and made it hang together in such a meaningful way. Building my ePortfolio has helped me understand what I am trying to do…I can explain my work better. It is different than saying what I’m majoring in. It is about explaining what drives me—what my work is.”

Capstone Projects

A few CIEL institutions have robust universal capstone projects overseen by one or more faculty. The interaction around the project is substantial with a real focus on integrating the project with the students’ concentration, supporting the students’ individualized goals, and often pushing the boundaries of their understanding by focusing on interdisciplinarity and/or a community engaged component. The capstone affords a substantial mentoring opportunity.

“Well… I think the fact that the thesis here at Hampshire is so independent and that you work closely with usually two people like that in itself has fostered our relationship and the structure of Division III fostered our relationship really well. We meet every week. Um, but it also really depends on the person ‘cause I, I got lucky enough to find two professors who were willing to be hands on and really close with me and I know that I as a student am someone who’s gonna seek that out from professors. So, I think in both ways, it was a lot of luck and a lot of having friends … who could kind of guide me towards people.”

And

“Div III was where I really saw my writing and my ability to really analyze grow. In all my course writing—and there was a lot of it—I felt like I was just writing for the professor, you know? And it was really rushed. Sometimes I didn’t really have time to revise it at all. Now I think I really know what writing is about. I have learned so much that you can’t even see, ‘cause I might cut it out entirely. Even though I liked learning the stuff, it doesn’t fit. And my committee is really—I really credit them with giving me the kind of feedback that is helping me. They ask questions and I have to be able to explain why this is ‘in’ and that is ‘out.’ And they are always giving me interesting things to read or telling me to meet with a research librarian or some such.”

The close relationship that forms through mentorship in an individualized project is a rare thing. In many elite colleges, a capstone project or senior thesis might be available to a small fraction of the student body through an honors program. An institution with a selective senior capstone ought to consider the gateways and barriers to inclusion in such a program. And, regardless of the specific curricular structure, there are other routes to connection between faculty and students. One such route is through informal work spaces, such as lounges, labs, shared dining spaces, et cetera.

Spaces

In some of our institutions, the spaces afforded greater contact among students and faculty—there were glaring differences between large institutions and smaller (even schools within a large school). In smaller institutions, there were more spaces, such as lounges or labs, that supported students’ congregating and working with or near faculty. Sometimes the classroom acted as that space when classes were constructed for greater collaboration. Informal contact is built into those schools’ structures and spaces and culture. Students often remarked on the value of the informal conversations afforded by collaborative work spaces—or even by the geography of campus.

“I see him in class but more so I’ll usually do a lot of work… I kind of work upstairs outside of his office. There’s a little table there so I interact with him there a bunch.”

Or:

“I work a lot in the Collaborative Modeling Center. It is a great space—really comfortable. And all the software—the programs I need are on those computers. I could be working there on my project and the person next to me is doing something totally different. When one of the faculty who also work there—like the faculty who kind of oversee the space—come in we all get to talking. I love seeing the connections in what we do. Sometimes we end up just chatting—not really just about our work. It’s kinda homey and just nice.”

We can probably all consider ways to build collaborative spaces—in lobbies, alcoves, outside of offices—and make them available to students. Having them work near us is not only a gift to them, it makes for pleasant connections for faculty too. Connection is reciprocal and we should remember the joy and motivation for our work that we get as a result of our interactions with our students.

Faculty Characteristics

The student descriptions of their mentoring relationships show faculty who were caring, warm, compassionate, had an orientation toward helping, and were generous with feedback. Even at our smaller institutions that are built on relational teaching, advising, and mentorship, there is variation in the quality of mentoring. And of course, there are differences in students’ receptivity to advice or in whether they “show up” for mentoring. What works for one student might not work for another. It is worth noting that becoming a strong mentor can, like anything else learned, take time and attention regardless of institutional structure, but it is not out of reach for anyone.

At most institutions, faculty do have some advising responsibilities. Although I have made distinctions between mentorship and advising, advising is one route into a mentoring relationship and there is evidence that careful advising in the first year can lead to a mentoring relationship later (Johnson, 2007). What is more, advising is a space in which the importance of mentoring can be openly discussed. In Making the Most of College (2001), Richard Light discusses his recommendations to his first-year students. After hearing about their personal goals, he suggests that one additional goal in their first year, and in each subsequent year, ought to be to get to know at least one faculty member well and to allow that faculty member to get to know them. In interviews upon graduation, his students report that this was the single most important piece of advice they received. Despite the fact that advising structures vary across institutions, professional development with regards to advising could support faculty in developing a relational approach themselves in addition to urging students to step up in developing mentoring relationships.

One of our students had a suggestion about faculty hires and professional development with regards to advising. They said:

“I think when people are hired here or if this doesn’t happen, I assume this happens, but if it doesn’t happen, it probably should, that when people are hired here, when they’re applying to work here, that they expect to have relationships with students. It’s small and we’re all working on our own things. So, you don’t always have a support network of like, okay, here are the English majors, here at the science majors. While there will be some, a lot of times, your friends are not in your field—it really is your [faculty]” committee that becomes an important constant.”

We certainly see the results of faculty mentorship that goes beyond their advisees of record:

“…for professors that weren’t on my committee, I probably got a little less time with them because they had their own advisees, but I’ve never had a professor say, ‘No, don’t come to my office hours.’ You know, [this professor] was never on my committee, but she went above and beyond to help me out with the end of my Division III project and just knowing what was—what I wanted out of a project versus what was expected of me.”

And another:

“I think that Hampshire definitely makes it a lot easier than other types of schools… Hampshire—its kind of this smaller space that really encourages the student/faculty relationships that I was able to make those connections. And especially with faculty here being so open and willing to meet with students and having office hours all the time, and I think it’s been really beneficial in forming those types of relationships.”

A diverse faculty has a critical impact on the mentorship that BIPOC students receive. Greater faculty diversity most surely increases the likelihood of all students finding faculty who see them and who support their work. And for white faculty who are mentoring students who do not share their racial, ethnic, or economic class background, it is crucial that we consider the ways we do or do not expect our students to be “like us.”

In these interview excerpts, I shared a number of student quotes in which students were inspired by their faculty mentors and wanted to be like them. But what happens if students do not see their future selves when they look at the faculty? Felicia Rose Chavez (2021) reminds us that we can easily create academic cultures that marginalize students from traditionally under-resourced communities. We have to let our students’ voices be heard and support their growth—even if it means letting go of some of the ways of thinking, writing, and being that we have valued. I hope that sharing students’ quotes in this chapter has shown the importance of elevating student voices. It is my strongest recommendation that as we work to increase mentorship on our campuses, we do it in concert with discussions about diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Cautions

In addition to the caution that mentoring does not simply perpetuate the culture of academia or of our disciplines if they are inequitable, there are a couple of other cautionary tales. There were big differences in what good mentorship meant to students and how they describe it. There is a difference in students’ level of expectation of contact. A mismatch can affect satisfaction. The best experience at one school might feel inadequate at others. which leads to dissatisfaction. Some colleges advertise a program with close advising and mentoring relationships. Students at these institutions have high expectations, and an advisor who is not so available or approachable as expected becomes a disappointment. At other programs, the very same advisor might prove to be more than a student expected. Whatever mentoring structure your institution creates, the appropriate expectations need to be set through your claims to prospective students.

Lessons

Thinking across the ways that mentors impact students, what stands out is the continuity that mentorship brings to the student experience. By working with a mentor over time, sharing their in- and out-of-classroom learning, students more thoroughly develop integrative thinking.

Even in this small group of progressive institutions, there is a good deal of variation along a number of dimensions that affect student need and opportunity for mentorship. For the most part, all participants we talked to had mostly positive experiences. The findings paint a compelling and positive picture of what strong mentorship can do for intellectual and personal growth and the development of ideas of a future self. The differences in how mentorships are set up on our campuses offer a glimpse into the diverse opportunities for contact among faculty and students in both planned and natural mentoring.

For any institution, it is possible to increase mentorship by keeping in mind the idea of a mentoring network. Some of the ideas that emerged through our conversations with students are that we would do well to:

-

Create spaces for informal contact.

-

Consider the inflection points in our curriculums where more student-directed work can be added under the guidance of faculty.

-

Have explicit conversations with faculty about what it means to mentor students.

It’s important for individual faculty to maintain an open stance during meetings with students, listening carefully for students’ interests, passions, and questions. These are well worth encouraging. As we learn more about our students’ interests, sharing information about resources and opportunities on and off campus can create pivotal experiences for students. And faculty can look for opportunities for conversation outside of class—perhaps lingering after class for conversations, encouraging students to come to office hours, or creating collaborative work spaces near their offices. And, though we are not trained therapists, there is a role for faculty in giving psychosocial support to students. Hearing the voices of students in our progressive institutions can give us all a better sense of the importance of, and methods for, building stronger faculty mentorship on our campuses.

References

Bowen, J. (2021). Teaching change: How to develop independent thinkers using relationships, resilience, and reflection. John Hopkins University Press.

Chavez, F. R. (2021). The Anti-racist writing workshop. Haymarket Books.

Felten, P., & Lambert, L. M. (2020). Relationship-rich education. John Hopkins University Press.

Higgins, M. C., & Thomas, D. A. (2001). Constellations and careers: Toward understanding the effects of multiple developmental relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 223–247.

Jacobi, M. (1991). Mentoring and undergraduate academic success: A literature review. Review of Educational Research, 61(4), 505–532.

Johnson, W. B. (2007). On Being a mentor: A guide for higher education faculty. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Lambert, L. (2018). The Importance of helping students find mentors in college. Gallup News, November 29. https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/245048/importance-helping-students-find-mentors-college.aspx

Light, R. L. (2001). Making the most of college: Students speak their minds. Harvard University Press.

McKinsey, E. (2016). Faculty mentoring undergraduates: The nature, development, and benefits of mentoring relationships. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.4.1.5

Mintz, S. (2021). What do we mean by educational innovation? Inside Higher Ed, Higher Ed Gamma, June 30, 2022.

Pascarella, E., & Terenzini, P. (1977). Patterns of student-faculty informal interaction beyond the classroom and voluntary freshman attrition. Journal of Higher Education, 48, 540–552.

Patterson, F., & Longsworth, C. R. (1966). The making of a college. M.I.T. Press.

Ray, J., & Marken, S. (2014). Life in college matters for life after college. GALLUP News.

Strayhorn, T. (2012). College students’ sense of belonging: A key to educational success for all students. New York: Routledge.

Wai-Ling Packard, B., Walsh, L., & Seidenberg, S. (2004). Will that be one mentor or two? A cross-sectional study of women’s mentoring during college. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 12(1), 71–85.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wenk, L. (2023). The Role of Mentoring in Innovative Progressive Institutions. In: Coburn, N., Derby-Talbot, R. (eds) The Impacts of Innovative Institutions in Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38785-2_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38785-2_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-38784-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-38785-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)