Abstract

University learning goes beyond developing knowledge and skills. It is a transformative process of learning to think and act differently. Mentoring programs support students to achieve success by helping them to think and act differently as learners and as future practitioners. This chapter examines two successful mentoring programs in the Faculty of Business and Economics at Macquarie University: the First STEP mentoring program targets undergraduate students in their first year to help them in their transition to university; the Lucy Mentoring program is for female undergraduate students in their final years of study and aims to facilitate their transition from university to professional work. Through the voices of participants we demonstrate how both programs contribute to creating a connected learning community, and support student transition, transformative learning, and employability.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Background

In this chapter we use the theme of a connected learning community. We explore how two of our programs in the Faculty of Business and Economics at Macquarie University build connections through the use of mentoring as part of the student journey, from the beginning of their undergraduate studies to becoming a professional. This aligns with the University’s strategic priorities (Macquarie University 2013) as well as the Learning and Teaching Framework (Macquarie University 2015). The First STEP and Lucy Mentoring programs are among a suite of extracurricular activities offered to provide small-group experiences to our diverse cohort of undergraduate students, to allow students to build personal connections. Both programs are explicitly designed to encourage success and relationship building. First STEP and Lucy Mentoring offer transformative learning experiences, by helping students to achieve their goals and develop. We have undertaken a survey of past participants which we report on later in the chapter. In order to assist others to implement similar programs, we elaborate on key factors for success as well as challenges.

Mentoring relationships in the journey through university support students in achieving their academic and professional goals by developing their sense of agency and purpose (Griffin et al. 2015). A central aim of higher education is that students graduate with a different perception about themselves and the world, and a different capacity for action (Case 2015). From this perspective, university learning is not just about developing knowledge and skills but is also a transformative process of becoming (Barnett 2004), or learning to think and act differently. Hence, how students think and act as learners and as future practitioners are dimensions of student success. As undergraduates, students are learning about themselves and their place in the world (Archer 2012, p. 11). This involves developing how they see themselves and the options available to them in any situation, as well as their capacity for action that is based on “self-awareness of goals and contexts” (O’Meara 2013, p. 3). Mentoring is one way to promote student agency (O’Meara 2013; Griffin et al. 2015) through interactions with more experienced mentors. These interactions between mentees and mentors support students in a process of becoming as they learn to develop and apply knowledge and capabilities that are central to professional work. Mentoring can be regarded as a discipline-specific transition strategy and is aligned with access to knowledge, rather than simply access to higher education, and has the potential to promote constructive modes of self-reflection. This view of mentoring is consistent with a conception of transition as becoming (Gale and Parker 2014).

Both First STEP and Lucy Mentoring feature elements common to many mentoring programs. A review of mentoring literature by Irby (2014) suggests these programs increase positive outcomes through: screening, training, support, providing accountability and an understanding of diversity, and setting time limits to mentoring relationships—both of our programs feature these elements.

Description of the Programs

Both programs are coordinated by University staff with funding provided by the University. The First STEP Program Manager supervises peer mentors and coordinates first year students and academics. The Lucy Mentoring Program Manager coordinates students and mentors. Mentors are not paid and volunteer their time. Both programs use a formal commencement event, training, and careful matching of mentors with mentees. The programs are strongly supported by the University Executive. First STEP was recognised with the institutional Vice-Chancellor’s Award for Programs that Enhance Learning for its contribution to student outcomes. The Vice-Chancellor personally supported the program by delivering a speech at the commencement event of First STEP.

First STEP Mentoring Program

First STEP is a program designed to improve the transition to university. It began in 2012 with 32 students, 10 academic staff, and 10 peer mentors (Cornelius and Wood 2012) and had grown to include 175 students, 22 peer mentors and 22 academic staff in 2015. The program design has been influenced by corporate mentoring programs, and combines one-on-one mentoring by teaching staff with group mentoring led by a peer mentor (Cornelius and Wood 2012). The use of peer as well as academic mentors is innovative and strengthens the program considerably. Previous reports on First STEP have discussed how the program was formed (Cornelius and Wood 2012) and evaluated (Cornelius et al. in press).

When they first enrol at university, students are invited to participate and can give input about their choice of mentor, as well as being given online training on how to make the most of their mentoring opportunity. Figure 3.1 outlines the timeline of the program in each semester.

Lucy Mentoring Program

Lucy Mentoring connects female undergraduate students with experienced business professionals in the workplace. It was initiated by the New South Wales Government in 2004 (Office for Women’s Policy 2004) and has since been offered at a number of universities. The program is voluntary and supports mentors and students (mentees) meeting and spending time together. Mentees learn to take the lead and drive the mentoring relationship towards their specific goals with the help of their mentors. Lucy Mentoring was introduced at Macquarie University in 2011 with 10 mentors and has grown to around 50 mentors in 2015. Students spend at least 20 h with the mentors, which can include shadowing or participation in workplace activities. Figure 3.2 outlines the timeline of the program across the year. First STEP and Lucy Mentoring staff work on their programs separately, however collaborate often during busy periods.

Evaluation

As part of our ongoing evaluation of the two mentoring programs, we conducted a survey of 50 former participants who had expressed willingness to keep in touch with the program after their participation. We recognise that negative accounts are less likely from those who expressed a desire to keep in contact, and that the likelihood of a response from a participant who did not enjoy the program may also be low. However, informal feedback from participants in the past has shown participants’ willingness to provide constructive feedback.

Mentors and mentees were asked to reflect on their experience in response to four guiding questions (see “Appendix”) and elaborate further as they wished. By using open-ended responses, we allowed the participants to decide what they most wanted to tell us about their experiences. This chapter privileges the use of direct quotes to convey the voice of the participants. Giving students and mentors a voice is a significant feature of the University Learning and Teaching Strategy, which encourages students as “partners and co-creators” (Macquarie University 2015). While research literature more commonly examines mentoring in a tertiary institution from the student perspective (Baker et al. 2015), our research also seeks to understand the mentors’ perspective.

First STEP mentees and peer mentors to date have ranged from 17 to 60 in age, with the majority aged 18‒25. Academic mentors range in age between 22 and 65. In both groups there is an even mix of males and females. Approximately 70 % of the students participating are domestic and 30 % international; citizenship details are not collected for academic mentors, although they are from a variety of cultural backgrounds. Lucy mentees are all female, ranging in age from 18 to 25, both domestic and foreign citizens. Lucy mentors are both male and female, range in age from 22 to 65, and are also both domestic and foreign citizens. Responses were proportional to the mix of participants across age and gender. However, very few responses were received from international student mentees; the study was conducted during the summer break which may have limited the responses from this cohort as they were likely to be overseas.

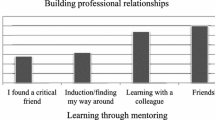

Building Connections Through Mentoring

Both mentoring programs align with the University’s strategic priority of creating a connected learning community (Macquarie University 2015); that is, a community that connects students, academic staff, and industry partners. As a result of participating in the mentoring programs, students develop greater confidence, improve their communication skills, and understand the value and importance of networking with their peers and professionals. Each program creates connections: for First STEP it is connecting students with peers and academics; for Lucy it is connecting students with professionals in industry.

First STEP: Connecting Students with Students and Academics

First year students apply to participate in the program by submitting a brief written application which includes information about their interests. Students are provided with online profiles of academic mentors and asked to nominate their top three preferences. Students are then matched with academic mentors, in groups of three to five students, as well as with a peer mentor. A diagrammatic representation is shown in Fig. 3.3.

Students choose to apply, and also have input into their choice of mentor. This design was deliberate as it mimics the development of informal mentoring (Allen et al. 2006). Informal mentoring—that develops spontaneously through the free choice of the mentee and mentor—is viewed as the gold standard and the most effective form of mentoring (Cornelius and Wood 2012). However it can be hard for mentees, without any skills or experience, to seek out mentors. Formal mentoring programs bridge the gap between students and people with experience and provide training on mentoring.

(Note—in including reflections from participants in their own voices, we will refer to them by culturally similar pseudonyms.)

Having had this facilitated experience, students gain confidence and skills and therefore are more prepared to form connections on their own in the future. Zain, a first year student, reflected on how he was nervous initially, but after meeting his mentor they formed a connection.

From the start, [my academic mentor] was really excited and like I was a little bit confused I thought, he is an adviser, I have to be formal and take it serious.’ But when he started talking after a few minutes, I got like really relaxed in front of him. … you just talk to him frankly and you are not scared that, ‘Okay I am not going to ask this question as I’ll look stupid or something’, so you are really frank with them, so you can get a lot of information from them.

Although more complicated than one-to-one mentoring, the administrative effort of creating the mentoring groups has substantial benefits because they offer multiple opportunities for students to form connections and seek support, as demonstrated in Fig. 3.3. Although formally the program only requires mentoring between the first year student and academic individually, and between the peer mentor and first year students as a group, informal relationships often develop, as demonstrated in the student reflections. Vivek, a peer mentor, mentioned that after seeing the benefit the students were receiving he “took this opportunity to also seek mentorship for myself”. Another peer mentor, Beverley, said of her relationships with her group:

I didn’t have any big expectations to begin with, but it actually worked out better than I thought it would be. At first I thought, ‘Oh this is just kind of easy work, mentees and academic mentors, like you’re being a bridge for them.’ But I guess in the end I found it was actually more my personal relationship with the students as well and I’m only speaking for the ones that I actually had contact with, some of them were a bit too difficult to contact and they just never made connections with me, but yeah, a few friendships actually emerged.

Peer mentors are in their later years of study, and organise individual meetings between the first year students and the academics. This reduces the administrative burden on the academic, and provides leadership experience for peer mentors. Commonly, peer mentors reflected that this role was harder, but also more valuable than they expected. Beverly reflected:

I thought it was going to be easy, I mean how hard can it be to link two people up? I did learn that it was actually quite a substantial amount of responsibility, that I actually had to organise and arrange for these meetings to work out … for me, this program was about connecting academics with students and I actually played a substantial role in that… not often do you get this responsibility, so it’s an honour to have this responsibility and for it to work out is a big achievement.

Hamid also reflected on how being trusted to organise things in his own way deepened the leadership experience.

One of the important factors of the First STEP mentoring program is the power and freedom handed over to the mentors to conduct and achieve the goals of the program in their own way. This ability to construct my own agenda and communicate with my mentees in the manner in which I wanted, allowed me to develop deeper and more meaningful interpersonal relationships.

Vivek similarly saw himself differently after successfully organising his group.

I was in constant touch with new first year mentees and also the academic mentor – to lead activities among them. As a result of this experience, I developed strong relationships with all involved and was much more confident of my communicability and further saw my role as quite influential.

Although not designed to provide formal mentoring to the peer mentor, both academics and peer mentors commonly report that an informal relationship develops as they work together to assist the first year students. Vivek said:

As a result of First STEP and my involvement, I was able to also develop a very good relationship with the academic, a great help indeed at times when personally I have been stuck in making decisions, needing advice or just having that sounding board to talk through things.

The peer mentor models professional behaviour, and reminds the student before the meeting of the time and location to ensure they are prepared, as well as gathering the group of students twice for social meetings—lunch on campus, or for an activity nearby.

The connections arising from the program are also important to the academics. One academic, Eva, reflected on the benefits of forming a connection without the barrier created by assessments:

I have been able to assist and motivate some of my mentees while gaining so much personally. As a staff mentor you have the opportunity to develop personal relationships with students without the responsibility of assessing them. As the students are all new to university, you try as a First STEP mentor to make the transition a little less stressful for them and I found this very rewarding.

James, an academic, reflected on how he not only benefitted from the relationship with his mentees, but from the insight it gave him into the journey of the second year students he typically teaches:

It was a reminder about how little they are aware of and how much they need to be coddled. This is not a suggestion that they are weak but rather that we forget how little we knew then. It made me sympathise with them more, and reminded me of how lost I first felt when I came to university.

Another academic, Mathew, similarly reflected on the fact it reminded him of the difference that simple things, like learning student names quickly, can make to the students.

When I first started especially as a tutor I would get to know all their names, certainly in the first half of semester. Probably in the last three years with the pressure of teaching and research commitments and so on, I think I slacked off on that. I think, for example, getting to know the students’ names and getting to know a bit about them became more random, more haphazard, I wouldn’t always make that effort. They’d be time pressures that would prevent it and I think being part of this mentoring process reminded me how useful it was to establish that rapport, so I’ve started doing that again.

Lucy Mentoring: Connecting Students with Professional Mentors

Lucy Mentoring is an extracurricular program for female students in their second year or above of undergraduate studies. Preference is given to disadvantaged students—those with disabilities, from a non-English speaking background, or the first in their family to attend university—as these students often have fewer opportunities to connect with industry through personal networks. Students submit a written application and are interviewed. As part of the application process, the following considerations are taken into account: their grades, their access to professional networks, their overall level of maturity and professionalism, and their motivation for wanting to participate in Lucy Mentoring. At interview stage, the following points are stressed to applicants: the need for commitment in the program (if successful); a thorough understanding of their current study, part-time work, and extracurricular commitments; and the ability to exercise flexibility. A major challenge for mentees is finding the time to meet with their mentors. We look for a genuine desire in the student to learn from someone more experienced and grow in their personal and professional development. Some interview questions have taken on the form of a role play where we ask the student to pretend to call their mentor and introduce herself over the phone.

Mentors submit an Expression of Interest to participate in the program. The Lucy Mentoring Program Manager usually meets with mentors face-to-face to explain the program in greater detail and answer any questions. Having face-to-face interaction helps with building rapport, and mentors frequently participate for several years.

Midway through the program, mentees meet as a group to share their experiences. At this point, there is usually a mixed response where some mentees are enjoying regular contact with their mentors, whereas others have tried but have not had much success in communicating with their mentors. Tips and strategies are shared as mentees discuss how they are overcoming challenges faced with their mentors. Mentees are also encouraged to build networks with each other during the program, to share ideas and meet together.

The main challenge for mentors and mentees is time. Mentees need to be flexible and appreciate that their mentors are extremely busy and so they sometimes may have to cancel a meeting at the last minute. In tackling how to get mentors to respond to mentees’ emails, one mentee gave a helpful suggestion that she had a good response rate from her mentor if she emailed half an hour before the start of her mentor’s workday. This is because she knew her mentor normally checked her emails on the way to work and by emailing her at this time, the mentee’s email would normally be one of the first emails in her mentor’s inbox.

At the conclusion of the program, mentors are given a small gift as a token of appreciation for volunteering their time and effort to support mentees. In recent years, the Program Manager has acknowledged mentors’ participation on LinkedIn (an online professional network) in the form of a simple “thank you” post. This information is shared with the mentors’ connections and is a good way to publicly promote the good work they are doing.

Supporting Student Transition Through Mentoring

Student transition into and out of university is about navigating change (Gale and Parker 2014). The two mentoring programs described here bookend students’ journey through their degree program, helping them to navigate change: First STEP supports students’ transition to university; and Lucy Mentoring supports their transition to professional practice.

Mentoring has been shown to have a positive effect on students’ transition to university, retention and skill development (Glaser et al. 2006). Interviews with First STEP participants at Macquarie University similarly found students felt their transition was eased through participating in the mentoring program (Cornelius et al. in press); and a recent study of the Lucy Mentoring program shows that students benefit from participating through increased confidence, greater self-awareness, and knowledge about their future careers (Smith-Ruig 2014).

Students journey through university in different stages. When they first enter university, they may decide to join First STEP to help them transition. As they become more familiar with their surroundings and learning, when they reach their penultimate or final year they may start thinking about life beyond university. Female students in their penultimate or final years are encouraged to apply for Lucy Mentoring as they prepare to transition out of university, and to learn about professional skills needed in the workplace, or to develop interview/networking skills.

First STEP: Independent Learning Skills

A number of skills acquired in First STEP are independent learning skills required to transition into learning at university and are a small step towards those required to “transition out” such as: attending meetings on time, setting an agenda, getting to know an academic, networking with other students, and writing professional emails. Emin said:

[My academic mentor] gave me some tips, to adjust my attitude towards study and my life. Because I got depressed a lot while I was studying, because I had so many failures and he helped me out. He said, ‘Do not think about consequences too much just do whatever, the thing that I like and focus on it.’ He gave me some time-management techniques and tips on writing, how should I focus on reading articles, because writing was my biggest weakness.

The program explicitly guides students in developing these skills through an online training module, weekly emails, a Facebook page, and attendance at several events. The program commences with a lunch networking event. In the first half hour, students meet peer mentors who set expectations for the program and provide students with a printed handbook that includes examples of how to write a professional email, tips for networking, and a template for goal setting. Then in the final hour academics arrive and meet their mentees, and there are short speeches as well from a member of the University Executive and a former student participant. This sets the tone that the program is something special. If students are unable to attend they have a one-on-one briefing with the First STEP Program Manager. In the first half of the semester there is also a careers workshop that encourages students to start building their résumé. Later there is a barbecue hosted by First STEP for all first year students in the Faculty. This advertises the program to other students who may participate in their second semester of university, and provides a good networking opportunity after the mid-semester break when returning students often feel nervous again after a few weeks out of university routine.

One of the most basic needs first year students have when transitioning is meeting other students. Emin reflects:

You try to make friends at university. Sometimes it’s difficult because everyone seems focused on their work and work so hard and are busy with their own life. Even now in my tutorial class I’ve got a lot of classmates but I hardly know any of them. With the mentoring program I see my peer mentor, I see my academic mentor, I get someone to talk to again. I get a chance to make friends, especially if I stay when we had a gathering … I still keep in touch with a lot of them, we say hi to each other because we know we’re on the same boat. In your class you don’t feel that.

For international students, operating in another language is perhaps the most important transition. Flora shared her concerns:

As an international student, it was my first time being away alone from my country and I was worried about what Australia and university would be like, and whether I would be able to fit in. Being part of the STEP mentoring program played an important role in my transition into Macquarie University. I was given the chance to meet new people who were also in the same situation as me since it was everyone’s first semester.

Lucy Mentoring: Supporting the Next Generation of Leaders

Lucy Mentoring is one example of how Macquarie University supports students in helping them achieve their aspirations and it provides an incubator for the next generation of leaders (Macquarie University 2013, p. 12). The program gives students a window into the corporate or professional world by linking them with mentors from the private, public and not-for-profit sectors. Daphne shared her experiences:

As a second year university student in the Lucy Mentoring program, there were a lot of new experiences. First suits. Navigating to corporate offices. Learning about office hierarchies. What it means to work for a service provider. Realising big businesses pay bigger taxes than me.

For many students, it is their first time interacting with professionals from industry, and the experience of learning to communicate with them via email, telephone, and in person pushes students out of their comfort zones. Isla reflected on the confidence she gained from participating in Lucy:

Through putting myself through a program in which I was the driver in developing a relationship with my mentor, initiating any contact and maintaining contact throughout the semester, my confidence has improved and increased. I am more readily seeking out opportunities to further develop my confidence and presentation skills and am excited for any chance I have to do new things. As one of the key initial goals of this program, this is a huge success for me.

A majority of students who join the program—initially unsure about what the future may hold once they graduate—find they have greater clarity about their future careers by the end of it.

The program has been successful as a result of mentors reaching out to their networks and encouraging them to participate. The Program Manager matches mentors and mentees based on information provided. There are instances where mentors and mentees are matched according to what the student is studying and the mentor’s relevant industry. In other cases, mentors and mentees are matched because they share a common background; for example, they are (were) international students, or a mentor who has a passion to build confidence in young women is matched with a mentee with high grades but who lacks confidence in soft skills. Mentors sometimes request to be matched with mentees in their final year as they are best able to provide practical help in the areas of applying for jobs, interview practice, and résumé assistance.

The Program commences with a networking welcome event where all mentors and mentees meet for the first time. There is a speech from a former mentor and former mentee. For new mentors, hearing about the experiences and challenges of former mentors and mentees is inspiring. Prior to the event, all mentees are briefed on the backgrounds of their mentors and are given their contact details. They are also briefed on expectations in terms of professionalism and conduct during their participation in the program. Mentees are encouraged to drive the relationship and be proactive in their relationship with their mentors. Anna, a mentor, commented that:

the experience of working with a mentee is only as good as the engagement of the student. During the program, my mentee always took the initiative to call me and keep in touch over email so that we could progress her goals within the timeframe of the program. She always put forward a plan of attack for our meetings. While I added my own views and agenda items, ultimately my mentee drove the process so that she got the most out of the program.

During the program, mentees may be supported in a number of other ways (such opportunities are not compulsory). For example, a former Lucy mentee now working as a professional ran a briefing workshop for Lucy mentees to help prepare them for the program. She discussed learning styles and different communication styles, and challenged mentees to be well prepared for each interaction with their mentors before, during, and in between mentoring sessions in order to make the most of their time together. One of the Lucy mentors volunteered to talk to the mentee cohort about negotiating for a salary increase as this was a topic she was passionate about. A contact of the Program Manager gave a presentation to the mentee cohort on how to create a good first impression, network effectively, and build rapport with other work professionals. Mentees were also invited to attend a workshop on body language and networking. These engaging workshops are helpful for mentees who are keen to gain practical tips on transitioning well from university to the workplace. It also gives them an opportunity to practise their networking skills as they interact with business professionals in a safe environment.

As a way to get mentors to network with each other, a breakfast networking session for mentors has been introduced, occurring midway through the program. This is an informal way for a smaller group of mentors to meet and share ideas with each other and staff members. They share the activities they are doing with their mentees and some of the challenges they are facing. In addition to the networking session, a LinkedIn group has been set up for mentors and mentees to share information. Mentees have to be persuaded and encouraged to share their thoughts on this forum, whereas mentors are less reluctant to comment and contribute. An informal buddy system for mentees has been introduced to encourage them to network and start building connections among their peers.

At the end of the year, there is a networking event where mentors and mentees come together to celebrate. Mentees give presentations and thank mentors for volunteering their time. A small number of mentees present on behalf of the mentee cohort.

First STEP

The information needs of first year students are often quite simple—most want to get to know the campus, make friends, and understand how university is different from high school. Once they get over these hurdles, other events in the program, particularly the careers workshop, can encourage students to consider future planning.

Nevertheless, conquering these hurdles can be quite transformative. Many students are initially apprehensive about meeting academic staff, and find their lecturers unapproachable. One of the most common surprises for students is as Jessica said, “the fact that academic staff aren’t so alien, that you might chat to them and they’re helpful.” Flora reflected on how her relationship with her mentor was much closer than expected:

Initially, I was quite nervous about meeting my mentor, as it was such a new and intimidating experience to talk to a lecturer in her office. However, my mentor was very kind and knew how to quickly put me at ease and make me feel comfortable. At the beginning of the program, I thought that a mentor’s task would be restricted to providing academic or career advice. So, I was deeply pleased to find out that our conversations would normally range from university topics to a lot of different areas of my life, such as self-confidence, stress, accommodation, and how to become a more positive and better person. I could see that my mentor was not just doing her job, but that she really wanted to be my friend and help me.

Jill was also surprised by the impact her participation had on her:

I gained a lot more from the program than I thought I would. Most importantly, I learned the importance that good mentoring can have on someone’s life. Thus, it encouraged me to become a mentor myself in the LEAP mentoring program (which is about mentoring high school students from a refugee background) and the Mentors@Macquarie Transition program; both programs are run by Macquarie University.

For a number of students who have been attracted to the program after previous failures, and have realised what it takes to succeed at university, find it is often quite transformative. Olivia said:

I had done a semester of university before, up in Darwin at the university there. I’d felt that I wasn’t involved in the university at all, other than attending my classes. There was a huge difference between what I expected from the university to what my experience was, and I didn’t really know who to talk to about that at that time. So when I was doing my enrolment form [for Macquarie] and I saw [First STEP mentoring], I was like, that’s probably a really good thing. [My academic mentor] was like, have I found it all right? Do I have enough time to study? Basically, he was trying to help me out with just being aware of, I’ve got an assessment that coming week, have I started preparing for it? He also helped me find when there were the extra maths tutorials. I definitely feel that it has made me feel more a part of the university.

Emin similarly thought:

I had a lot of questions that I had through study experience from before I came to university. Because I’m a returning student, I had so many failures the last time when I was studying at university. I kept all the questions, I made a summary, and asked [my academic mentor], ‘How should I face these problems?’ He gave me a lot of tips and it was very beneficial for my start of university learning.

Students discussed the realisation that they are now fully responsible for their learning. As Jessica put it: “Other than going to your tutorials, and depending if you’re the kind of person who goes to their lectures or listens to them online, you don’t need to really be a part of the university at all. You get out of it what you put in, basically.”

The First STEP program handbook and online module both contain information on setting goals, and creating meeting agendas. Students are encouraged to go in with an agenda even if their meetings are informal. In the final meeting of semester students are encouraged to look back and reflect on what they have learnt.

Lucy Mentoring: Reflecting on the Journey

Mentees are required to submit a reflective journal at the end of the program to share what they have learned. The reflective journals are personal reflections on what mentees have enjoyed or found challenging in the program.

The beauty of the program is that it allows students to interact with industry professionals in a safe environment. Mentees are encouraged to use their judgement and discretion, to make mistakes and ask for feedback. This can be challenging as there are no right or wrong answers. The Program Manager has fielded questions from mentees such as “What is the etiquette on who pays for coffee?”, or “How many times should I keep emailing my mentor before I pick up the phone and call him or her?” Isla commented about how she grew in confidence as a result of being in the program.

The Lucy Program pushed me out of my comfort zone by making me responsible for each interaction with my mentor. Beyond my part-time jobs, I had little experience communicating with professionals via email, telephone, or even in person. It was a valuable experience to learn how to engage in small talk with a professional – which had previously seemed awkward to me – how to set up meetings, and how to ask my mentor directly for help on a project or for input regarding my résumé and LinkedIn profile.

The benefits for mentees in this volunteer program are considerable. Anna shared a description of her interaction with her mentee:

Before my very eyes, this shy student blossomed into the most confident young woman. During our short time together, she managed to secure not one, but two (!) vacationer positions at Big 4 accounting firms. She told me that she could not have obtained those offers without my help; however, I put them down to her hard work and courage to put the strategies we discussed into action.

Samantha reflected on mutual benefits and learnings from participating in Lucy Mentoring:

Despite my mentor not working in my area of study, I was still able to gain valuable experiences about how a small business is run and was also able to share my knowledge gained at university with my mentor. In this way, my mentor and I were able to learn from each other. … This will definitely allow me to evolve my career path. I have been able to learn and do things which I would not have been able to do without the help of the Lucy Mentoring program.

Janet reflected on what she got out of being in the program.

I was mentored by a highly driven and successful male mentor from a completely different industry, which made every session exciting and extremely insightful. My mentor is ambitious and supportive but above all, he is honest and authentic. Not only did he give me the confidence to believe in my own potential, he also taught me to accept truths about my weaknesses and rise above them. That key learning has changed the way I perceive and handle situations. I was more driven to put myself in instances I used to avoid, be it networking or speaking at events. Above all, I was constantly encouraged to test myself and discover my limitations. Even now, working in a profession that dislikes failure, that very key learning has given me the motivation to speak my thoughts more confidently.

Success Factors and Challenges

Both mentoring programs are well embedded into the University. Each rely on a number of factors for success and are faced by challenges that must be managed for the programs to remain sustainable. One of the main challenges for both programs is time. Participants are required to navigate time management well in order for the mentoring relationship to succeed. In this section we look at the challenges and success factors for each program.

First STEP

Peer Mentors

The most commonly mentioned key factor to the success of the program, by both students and academics, is the role of the peer mentor. Mateo, an academic, reflected:

I think that having the support of a peer mentor is a must. As academics, we have limited time so having the support of peer mentors was great; for example, organising my meetings throughout the semester. In this regard, I have had two opposite experiences in the program so far. One semester my peer mentor was not proactive so I had to do pretty much all the work (re. contacting my mentees and organising). That was a tough semester. On the other hand, last semester was awesome because my peer mentor was excellent. She was very proactive and helped me a lot so everything run smoothly.

His reflection makes clear that the peer mentors can be the greatest risk to the success of the program. We endeavour to mitigate this through training at the beginning of each semester, and weekly contact with the Program Manager. The most important solution is for all parties to communicate when things are not going to plan, as the Program Manager can only intervene when it becomes clear there is a problem. Expectations are set during peer mentoring training, held prior to the start of semester, and reinforced during weekly emails between the Program Manager and peer mentors.

Time Commitment and Recognition of Volunteers

Academic mentors volunteer their time, which limits the size of the First STEP program to the number of available academics. The total commitment required over the semester is approximately 20 h, for which academics receive three service days towards their workload. However, given the number of other demands on academics, and the number of other programs and committees clamouring for participants—some of which are more public and provide more recognition—it is difficult to recruit more than the number required to replace those lost to attrition (around 20 % per semester). Time and recognition are commonly cited as limiting factors for undergraduate mentoring programs (Baker et al. 2015).

Potential solutions would require more resources. For example, part-time staff are currently not utilised. A solution to the limited supply of academics would be if funds were available to pay part-time academics for 20 h. A number of institutions have achieved success by offering internal funding to increase mentoring of undergraduate research students (Baker et al. 2015), although finding similar funding for a first year mentoring program may be more challenging. Alternatively, mentors could be drafted into the program by including it in their professional development plan; however, this may not be the best way to find mentors who are fully engaged.

Peer mentors also volunteer their time. Many students are seeking to add leadership experiences to their résumé, and the recognition provided by the program, along with a certificate and contribution to GLP (a university extracurricular program that appears on student transcripts) are attractive. The large student population also results in a sizeable pool of potential peer mentors, and recruitment of peer mentors is not a challenge.

Student Recruitment

The First STEP program started with a pilot of ten students, and grew each semester until reaching the current maximum of 100 students per semester. As the program has grown, word of mouth has spread and the program has begun to advertise itself, and perhaps even the University, as Zain said, “This process was so helpful for me that I actually convinced my younger brother to come and join Macquarie so he is also going to come next semester.” Recruitment of first year students is consequently also not a challenge. Demand currently is met by supply—generally the program is oversubscribed in the first semester of the year so some students are waitlisted; they can then get a place in the second half of the year, when enrolment of new students is typically much lower.

However, the size of the program is limited and operates at full capacity with current resources. There is a danger that if it were to become more popular, and students had to be turned away, this could be a negative experience. The program was not available when some peer mentors were first year students, and some mention how they felt they missed out. Vivek says, “Many times, during the program as a peer mentor, I have told my mentees as to how lucky they are to be part of it and how I would have loved to have this opportunity [when] I was a first year student—the thoughts which many other students share.” This is a challenge that needs active monitoring.

Lucy Mentoring

Time

The main challenge for Lucy mentors and mentees is finding the time to meet. During the interview stage and briefing sessions, mentees are encouraged to be flexible and highly organised in order to balance their study and part-time work schedules with meeting the demands of the program. The method of communication in the mentoring program can take different forms—depending on time and distance, mentors and mentees can choose to meet up face-to-face, or correspond via email, phone, or Skype. As some mentees live and study a considerable distance from their mentors’ workplace, some flexibility is required in order to make the mentoring relationship work well. Jeslyn, a mentee, commented:

I felt challenged when I found myself having to give up other activities to be part of the program. Travelling distances can also be quite time consuming. I had underestimated the amount of time and energy that would be dedicated to the mentoring program. The pressure forced me to be more organised with my time. I think this could be highlighted to future mentees.

From a mentor’s (Anna) perspective:

Naturally, the biggest challenge for mentors and mentees is time – it can be difficult to schedule meetings around work and study commitments. However, I would have to say that face-to-face meetings and giving the mentee an opportunity to experience the working environment are extremely important so that they can develop their professional skills. Students should remember that any mentor will be happy to set aside time for their mentee, but the responsibility for organising these meetings rests on the student.

Some mentors may use participation in the mentoring programs as part of their professional development. In promoting Lucy Mentoring, the Program Manager suggests ways for mentors to include mentees in their days to make it easier for them to complete the 20 h. For example, a mentee could shadow their mentor for half a day and observe what their mentor does in his or her role. If a mentor is having a lunch break, their mentee could join them for an informal catch up. These approaches can help to relieve some of the pressure of setting aside additional time to meet on top of mentors’ schedules.

The mentoring relationship is an informal one, where the mentor and mentee build a professional and personal relationship through activities that are primarily career related. In some cases, mentors may be keen to mentor; however, in reality, the demands on their work and role may prevent them from being able to provide their mentees with a good mentoring experience. It is important that the mentor is committed to the program otherwise mentees are disappointed when mentors are too busy to meet up with them or do not return their calls. Potential mentors should consider questions such as the following before deciding to participate as mentors:

-

Do they have the capacity to sustain the mentoring relationship with their mentees?

-

Are they in the middle of transitioning to another role?

-

Are they being promoted shortly?

-

Are there other factors to consider outside of work which may impact on their commitment?

-

Are they going on extended leave during the mentoring period?

If mentors are still keen to participate but are time poor, one option is to co-mentor with another colleague. This has been the exception rather than the rule in Lucy Mentoring.

Motivation and Professionalism

The success of the Lucy program depends on the maturity and professionalism of mentees who need to be able to navigate a professional relationship with their mentors. Mentees are given support and training before the program commences on what to expect and the importance of establishing a good rapport with their mentors at the start, and they are encouraged to have clear mentoring goals.

Care is given to match mentors and mentees appropriately. It is important to understand mentors’ motivations and address any issues or concerns at the start. Mentors work in different ways, with some wanting a lot of structure and direction and others requiring less. If mentors have a good experience, they are more willing to return the following year or promote the program to their contacts and networks.

In order to deliver and maintain a quality program the Program Manager should keep in touch regularly with each mentor and their mentee. This level of service can be difficult to maintain as the numbers grow; however; it is a good opportunity to offer mentees. Continuity and service are critical success factors for the Program Manager as they build and maintain relationships with the mentors.

Relationships

Lucy Mentoring works well when mentors and mentees are committed, have set down clear expectations, and discussed goals of what they would like to achieve in the program. This should be discussed at the start, ideally at their first meeting. Mentees need to understand their own time commitments and responsibilities in order for the relationship to work well.

Mentors have given feedback that it is discouraging for them when mentees frequently decline their invitations to catch up. This reflects badly on the mentees and also the University if this is the experience for mentors.

It is important to stress to mentees that mentoring relationships can vary based on the mentor/mentee relations. Regardless of their mentors’ level of seniority, expertise, and background, mentees do benefit from each interaction with their mentors if they are committed to growing and developing in the program.

Setting goals and defining expectations at the first meeting are critical for mentoring success. Katrina, a mentor, shared her tips for success.

Goal setting at the start of the mentor/mentee relationship is critical. Both parties need to clearly understand the outcomes they are seeking so the program can be tailored and time together allocated to meet the objectives. My other keys to mentoring success are trust, honesty, and good communication. These days everyone is busy, everyone seems to have a million priorities, and every person in business has someone wanting their time and attention, so it is important the mentor and mentee are clear with each other and can be a bit flexible.

Isla shared how she set expectations and communicated her mentoring goals with her mentor.

For me personally, critical to the success of the program was establishing my expectations and relating them to my mentor. Before the Lucy Program kicked off, and even before I met my mentor, I wrote a list of key areas that I need to improve in and the different activities and methods I thought a mentor could help me to improve. Later, when I met my mentor at the Lucy Program launch, I discussed my personal goals for the program and at our next meeting we set up a basic schedule to stick to and our communication methods for the rest of the program. This involved weekly email catch ups as well as meeting up for a coffee regularly to go over things, specifically regarding my career goals. Establishing expectations from the start helped me to maintain my mentoring goals and priorities and gave my mentor a picture of what he could do to mentor me in these areas.

Future Directions

Both mentoring programs have reached a mature phase. Numbers are unlikely to increase without an increase in resources, and both programs in the future will focus on refining the program in response to feedback, building stronger links between programs, and ensuring the programs remain current in the face of change in the university sector and in industry.

The size of the First STEP program is unlikely to grow. Future directions for mentoring in the Faculty may involve the creation of additional resources for online support and training. The Program Manager also works closely with other current mentoring programs, not only Lucy, but elsewhere in the University. Other areas of the University are now using academic mentoring programs. Future directions for mentoring at the University overall may involve alumni mentoring, or online mentoring programs, both of which have been successful at other Australian universities. First STEP currently utilises an online page and a Facebook page. During their transition to university, students are coping with new platforms, and introducing new ones would only add to their burden, consequently future technological innovations (such as a mobile phone app) are less likely unless well resourced. A recurring suggestion among peer mentors is a networking event among peer mentors, as Hamid said, “Spending more time as a team, in terms of the mentors [would] go a long way to build a sense of community within the program.” This will be incorporated into the program in the future.

If numbers continue to grow in the Lucy Mentoring program, it will be important to maintain the quality of the program by ensuring there are enough staff to support participants well. The use of digital technology would be helpful in promoting the program and sharing resources and information between mentors and mentees. Subject to budget constraints, a mobile phone app could be used by mentors and mentees to share their experiences more broadly. This would help mentors who are new to mentoring learn from other mentors and mentees.

Conclusion

Mentors and mentees benefit mutually from the mentoring relationship. Mentors have said that they mentor as a way to give back, but also because they wish they had had a mentor when they were at university. They see the benefits of sharing their mistakes with mentees so they do not have to make the same mistakes. Mentors participate in the program in order to help develop our future leaders. Katrina reflects on how mentoring supports future leaders:

Ultimately, the role of a mentor helps make you a better leader. It gives me the opportunity to reflect on my own journey so far, revisit some of the mistakes I have made and challenges I have faced. This allows you to give stronger support, advice, and encouragement and, in doing so, make a small contribution to what tomorrow’s business world and our future leaders might look like.

In the process, mentors have shared that they learn as much about themselves as they do about their mentees. As mentors reflect on their personal journeys with someone less experienced, it helps them to hone their leadership and coaching skills and gives them an opportunity to be challenged by fresh ideas and perspectives. A benefit for mentors is the opportunity to grow their own networks. Sandy shared this about her experience:

As a first-time mentor in the Lucy program, this opportunity has renewed my passion for developing and coaching people. I have also benefitted from the various networking sessions which has assisted in growing my professional network. Since joining Lucy, I have been able to access a greater network of like-minded people that is proving to be very valuable in my current role.

Sally, a mentee, reflects on how her participation in the program affected her:

The activities I participated in during the program enabled me to gain numerous insights that now shape the approach I am taking to my career. On a deeper level, the relationship built with my mentor has provided me with an important source of encouragement and support. As I enter my final year of university and start applying for jobs, I do so with greater confidence. I am more aware of what I’m entering into and am looking forward to both the challenges and opportunities it will bring.

Through our study of participants’ reflection on these programs we are increasing the body of knowledge about mentoring programs, in the voices of the participants, so we can learn from each other and from other mentoring programs. Mentoring has had clear, positive outcomes for participants in our programs. At these stages in our students’ higher education journeys, we recommend structured, supported, formal mentoring programs to inspire transformative learning and successful outcomes.

References

Allen, T. D., Eby, L. T., & Lentz, E. (2006). The relationship between formal mentoring program characteristics and perceived program effectiveness. Personnel Psychology, 59(1), 125–153.

Archer, S. M. (2012). The reflexive imperative in late modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, V. L., Pifer, M. J., Lunsford, L. G., Greer, J., & Ihas, D. (2015). Faculty as mentors in undergraduate research, scholarship, and creative work: Motivating and inhibiting factors. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 23(5), 394–410. doi:10.1080/13611267.2015.1126164

Barnett, R. (2004). Learning for an unknown future. Higher Education Research and Development, 23(3), 247–260.

Case, J. M. (2015). A social realist perspective on student learning in higher education: The morphogenesis of agency. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(5), 841–852.

Cornelius, V., & Wood, L. N. (2012). Academic to student mentoring within a large Australian business school. Asian Social Science, 8(14), 1–8.

Cornelius, V., Wood, L. N., & Lai, J. (2016). Implementation and evaluation of a formal academic-peer-mentoring program. Active Learning in Higher Education. DOI: 10.1177/1469787416654796.

Gale, T., & Parker, S. (2014). Navigating change: A typology of student transition in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 39(5), 734–753.

Glaser, N., Hall, R., & Halperin, S. (2006). Students supporting students: The effects of peer mentoring on the experiences of first year university students. Journal of the Australia and New Zealand Student Services Association, 27, 4–19.

Griffin, K. A., Eury, J. L., & Gaffney, M. E. (2015). Digging deeper: Exploring the relationship between mentoring, developmental interactions, and student agency. New Directions for Higher Education, 2015(171), 13–22.

Irby, B. (2014). Editor’s overview: A 20-year content review of research on the topic of developmental mentoring relationships ring journal. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 22(3), 181–189.

Macquarie University. (2013). Our university: A framing of futures. Retrieved from http://www.mq.edu.au/our-university

Macquarie University. (2015). Learning for the future: Learning and teaching strategic framework 2015–2020. Retrieved from https://www.mq.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/6878/L-And-T-Strategic-Framework-White-Paper-2015-FINAL.pdf

Office for Women’s Policy. (2004). Lucy mentoring program participant manual. Retrieved from http://www.dpc.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/82962/Lucy_Manual_-_Updated_July_2010.pdf

O’Meara, K. (2013). Advancing graduate student agency. Higher Education in Review, 10, 1–10.

Smith-Ruig, T. (2014). Exploring the links between mentoring and work-integrated learning. Higher Education Research and Development, 33(4), 769–782.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: Prompts for Participant Reflections

Appendix: Prompts for Participant Reflections

-

Tell the story of your participation in the mentoring program—for example:

-

How did you hear about it?

-

What was your motivation for applying?

-

What was your experience as a participant in the program?

-

How did your participation affect you?

-

-

Talk briefly about any factors that may be critical to the success of the program. These may or may not be part of the program.

-

Talk briefly about any challenges you may have faced in the program.

-

Talk briefly about any changes you might suggest to improve the program for future participants.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chung, C., Dykes, A., McPherson, J. (2017). Mentoring for Success: Programs to Support Transition to and from University. In: Wood, L., Breyer, Y. (eds) Success in Higher Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2791-8_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2791-8_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-2789-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-2791-8

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)