Abstract

The contemporary economic system developed by China in the last two decades, supremely successful in achieving economic growth, defies traditional classification. It has been variously defined as socialist (by Chinese leaders), capitalist (Kornai), state socialist (Coase and Wang), political capitalism (Milanovic), a unique system with features of both socialism and capitalism not conforming to either system (Kolodko). This essay seeks to support, substantiate and develop Kolodko’s notion of the uniqueness of China, while expressing greater pessimism than Kolodko about the economic, social and political sustainability of that system, its merits as a beneficial engine of globalisation and growth, and its exportability to other countries in the developed West.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL Classification

1 Introduction

Grzegorz Witold Kolodko is a man whose volcanic intellectual interests and prodigious productivity have spanned broadly over both time and space. Time, with his best-selling book trilogy devoted to the Past, the Present and the Future, and space not only as a traveller to almost all the countries of the world,Footnote 1 and a runner in 50 marathons worldwide,Footnote 2 but as a most knowledgeable explorer of China.

His publications in Chinese include four books and over fifty papers and journal articles (which by themselves would be a respectable scholarly output for a lifetime); and he appears regularly on Chinese television channels. He also wrote extensively in various languages on the Chinese economy, especially on its current economic model, which he regards as unique—combining elements of capitalism and socialism without conforming to either model. The title of his conference paper published as Kolodko (2018a) originally was: “Capitalism or Socialism? Tertium datur”, for he argued that in present-day China “a unique internal convergence is taking place. Features of socialism intermingle with essentials of capitalism and vice versa, creating a new, different quality.” His recent book on China, published in Polish in 2018, “Will China Save the World?” is forthcoming in English (2019) by I. B. Tauris and Bloomsbury. It investigates the economics and politics of rising China and its implication for globalization and the future of the world economy, polity and culture. That title is even more telling and positive.

In this essay I would like to support, substantiate and develop Kolodko’s notion of the uniqueness of the current Chinese economic system, and at the same time take a more pessimistic view on its economic, political and environmental sustainability, as well as its exportability. The current challenges to the sustainability of the world economy under current policies do indeed require new institutions and policies: these can only partly be learned and copied from China, namely the broad range and high intensity of economic policy instruments mobilised there.

2 China 1949 to End-1990s

The Chinese Communist Party, that came to power in 1949, after the completion of post-War reconstruction around 1952 followed the Soviet model of central planning, with the 1st five-year plan 1953–1958 and the first two years of the 2nd five-year plan, concentrated in the Great Leap Forward: dominant state enterprises; land reform and land distribution to peasants; encouragement for the establishment of agricultural cooperatives which then become compulsory and merged into large collective farms; priority to heavy industry, a massive investment drive and other features of the Soviet-type system. There followed a period of restructuring and recovery, with priority given to agriculture (1961–1965), the 1966–1976 turbulent decade of the Cultural Revolution, with the resumption of growth (1970–1974), the rise and fall of the Gang of Four (1974–1976) and the post-Mao interlude (1976–1978).

Since 1978, with the end of the Maoist regime, China undertook a slow and gradual transition to socialism, with a predominant role of state property and enterprise, the granting of land to private peasants through long-term transferable rentals (similar to the arenda that spread in the Soviet New Economic Policy of 1921–1926), and the growth of locally based Town and Village Enterprises (TVEs), similar to cooperatives run on a territorial basis but able to mobilize local entrepreneurial energies and to reach very large sizes. There was an egalitarian commitment, but without the economic participation of workers, who were not allowed to associate into unions or to strike (and without political democracy given the political monopoly of the Communist Party).

Planning was centralised, but the excess demand and shortages that characterised the Soviet-type model were not there, because prices were set at artificially low level below market-clearing only for minimum amounts of goods, necessary to an egalitarian distribution policy. For the rest, goods were sold at market-clearing prices, not in black markets but legally, a typical two-tier pricing system (dual track pricing). Obviously the price in the free market segment was higher than the single price equilibrium price that would have prevailed without the sales at a lower subsidised price; but the price difference between the controlled and free segments did not replenish the liquidity of private black-marketers as it did in the Soviet system. In China the excess liquidity of economic agents was siphoned off into the state budget, which was the only beneficiary of the higher free price, thus preventing shortages to arise.

3 The Rise of the Current Chinese System

The subsequent evolution of the Chinese system saw the beginnings of a transition in the opposite direction, from socialism to forms of capitalism, with the legalization of private enterprise, the creation and dissemination of Special Economic Zones to welcome foreign direct investment (FDI) on favourable terms, the privatization of state enterprises and assets (that began in 1997 and accelerated in 2005), including TVEs (although it is not clear whether their disappearance by the end of the first decade is due to their actual privatization or liquidation or simply to the facilitation of their registration as private, almost a purely cosmetic administrative re-classification by a stroke of the pen). Officially, the private sector is dominant from about 2001 onwards, but the distinction between the public and private sectors is rather uncertain, also because of the use of 10 different ownership categories in official statistics.Footnote 3 In any case the state retains the monopoly of land ownership, and a dominant stake in the property of banks thus affecting greatly the quantity and cost of credit available to all enterprises, private and public. The state control of banks is used to plan the volume and direction of investment, and leads to “soft budget constraints”, without producing shortages of goods in the form of repressed inflation but rather other phenomena of financial repression (such as an occasional unsatisfied demand for an artificially undervalued yuan).

The egalitarianism of the 1980s was abandoned and even reversed: in 2017 Forbes listed 395 dollar billionaires in China, but the China Rich List of the Hurun Report 2015 (Financial Times 16/01/2016) indicates a number of dollar millionaires that rose 8% to reach 3.14 million people in 2015, and a number of 596 dollar billionaires higher than the equivalent number for the US. In 2017, the richest 1% of the Chinese population concentrated 1/3 and the poorest 25% only 1% of the country’s wealth; the Gini coefficient for incomes of 2012 was 0.49, reduced slightly to 0.47 in 2015, surpassed only by South Africa and Brazil, compared with 0.41 in the United States.

The authoritarian and repressive character of the Chinese political regime, on the contrary, strengthened (economic liberalisation and political centralisation went hand in hand also during the Soviet period of New Economic Policy, see Nuti 2018a). Article 35 of the Chinese Constitution in theory guarantees “freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration.” But the preamble of the same Constitution confirms the power of the Party, and Article 1 prohibits “the perturbation of the socialist system by any organization or individual”.

China’s transition from socialism to a market economy was completed with its gradual opening to international markets, which culminated with the accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. In exchange for access to the markets of the other WTO members, China promised economic reforms, but it did not obtain the treatment reserved to a “market economy”, the lack of which involved the possible imposition of protective tariffs based on the (higher) costs of third countries. China expected that this temporary treatment should cease after 15 years, whereas tariffs have been maintained and increased over time, leading China to sue the EU before the WTO. The US supported the EU stressing the precedent of other transition economies (Poland, Romania and Hungary) that also had become members of the WTO as non-market economies on the same conditions as China. In December 2017 the EU approved new rules that no longer allowed to consider China as a non-market economy but retained ad hoc the use of third countries costs and prices, thus validating the maintenance of additional barriers.

Nevertheless the Chinese President Xi Jinping repeatedly confirmed (e.g. in January 2017 in a long speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos) China’s commitment to and support for globalization, much more clearly and energetically than other global leaders (with US President Donald Trump declaring almost at the same time “America first!” and protectionist plans).

At present, a trade war started by President Trump in the attempt to reduce the US trade deficit with China has been escalating, with Chinese retaliation and US counter-retaliation. In Asia, paradoxically, Trump’s protectionism has cleared the way for China to increase its regional influence at the expense of the United States. But the dispute over China’s status as a market economy will be controversial and time-consuming, not least because there is no internationally agreed definition of a market economy.

The trade war is likely to be lost by the US, simply because its trade deficit is ultimately the consequence of a budget deficit and of savings lower than investment (for national income accounting identities necessarily imply that trade surplus, budget deficit and investment in excess of savings should always add up to zero by definition). But the imposition of tariffs, even if inadequate to reduce the US deficit, threatens to bring about a worldwide recession.

4 The Challenge of Present-Day China’s Classification

The classification of the Chinese economic system today seems to defy traditional criteria.

Socialism? “We heard from the Chinese leader at the Congress of the ruling party that “Socialism with Chinese characteristics is socialism and no other—ism.” (Berthold 2017: 31).

Capitalism? Kornai (2013, 2016) distinguishes between the socialist system—with public property and central planning, characterised by the presence of shortages, with full employment but unable to innovate—and the capitalist system—characterised by systematic surplus productive capacity and unemployed labour, but highly innovative. Kornai classifies the Chinese system as capitalist, precisely because of the absence of shortages and the presence of a surplus and of innovation capacity. However Kornai (1980a, b) considers the shortages as a result of soft budget constraints rather than of prices artificially kept below their market-clearing level. Yet undoubtedly the Chinese economy is suffering from soft budget constraints, in the form of credit and subsidies to enterprises, while not suffering from shortages. In the characterisation of systems followed by Kornai the existence of a market economy is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the realisation of political democracy. Politically authoritarian market economies are perfectly possible; therefore the authoritarian character of the Chinese system in Kornai’s view does not alter its capitalist character.

State capitalism? The prevailing characterisation, both in economic journalism (e.g. The Economist, 6/10/2012) and in scientific literature (Coase and Wang 2012, 2015; Naughton and Tsai 2015) favours the term “state capitalism”, in view of both the high weight of public enterprises and the high intensity of government intervention in economic affairs. However, Lenin had used that label to designate a temporary, transitional state on the road to socialism, whereas there is nothing temporary or transitional about the current Chinese system.

Political capitalism? Milanovic (in his forthcoming book Capitalism Alone, Harvard University Press, 2019), defines the current Chinese system as “political capitalism”, following Weber, i.e. involving “the use of political power to achieve economic gains”. Milanovic quotes Weber (1904b: 21): “The capitalism of promoters, large-scale speculators, concession hunters and much modern financial capitalism even in peacetime, but, above all, the capitalism especially concerned with exploiting wars, bears this stamp [acquisition of wealth by force, political connection or speculation] even in modern Western countries, and some … parts of large-scale international trade are closely related to it.”

Weber developed this concept further in Economy and Society: “political capitalism exists … wherever there [is] tax farming, the profitable provision of state’s political needs, war, piracy, large-scale usury, and colonization” (1922, Part I, Chapter III; Milanovic 2019).

Such system gives bureaucrats great power, but also responsibility for the realisation of high economic growth, needed for the legitimation of its rule. Milanovic consider Deng Xiaoping as the founding father of modern political capitalism, an approach that combines private sector dynamism, efficient role of bureaucracy and one-party system. This is why Deng was particularly opposed to a multiparty system, a tripartite separation of powers and a Western-type parliamentary system (Milanovic 2019). Such a system requires, in order to keep private capitalists under control, an arbitrary and selective application of the rule of law, and therefore it involves congenital vulnerability to corruption, as the elites apply legal rules to themselves and to political opponents at their discretion. “… these organisations are not too dissimilar from the mafias. This creates politico-entrepreneurial clans and represents the skeleton of political capitalism around which everything else revolves.” (Milanovic 2019).

Beside China, Milanovic lists 10 other developing countries characterised by political capitalism, ruled by a single party (or a de facto single party when other parties are permitted to compete but not allowed to win elections on their own) in power for several decades, after a successful struggle (mostly violent, including civil wars) for national independence, under the leadership of a left-wing or communist party. They are Vietnam, Malaysia, Laos, Singapore, Algeria, Tanzania, Angola, Botswana, Ethiopia, Rwanda, all characterised by an impressive growth performance over the past 30 years and very high current corruption rankings. Milanovic’s recent reflections on the Chinese system (2018) speak of “Hayekian Communism”, economically a market-driven capitalist system with private property and enterprise, politically run by a monopolistic Communist Party.

A unique new system? Kolodko, as we have already indicated, considers China as a wholly new system, a third alternative that combines elements of capitalism and socialism without corresponding to either. “One can say that a hybrid in the form of socialist capitalism or—if you wish—capitalist socialism is developing there; a sort of Chinism” (2018a: 22).

5 My Own Changing Assessment

My own assessment of China’s present day economic system also has been changing over time, reflecting both the Chinese evolution and its ambiguity and ambivalence. In my teaching materials of the early 2000s and Nuti (2018a) my economic system taxonomy used a 0 or a 1 to indicate the absence or significant presence of four components of socialism:

-

A. public property and enterprise,

-

B. equality,

-

C. economic democracy and participation,

-

D. macroeconomic control.

I labelled systems by their ABCD values: contemporary China was 1001, similar to the Soviet model 1101 except for China’s greater inequality (B=0 with respect to Soviet B=1, in spite of Soviet distributional privileges in the access to underpriced goods).Footnote 4

In a recent lecture (Nuti 2018b) the high element of macroeconomic control, even under full exposure to domestic and international market forces, made me classify today’s China still as ABCD=1001, also because of important residual public property elements (all land, banks, most FDI). I believe that China’s use of economic policy instruments is particularly active, while certainly today’s capitalism has lost most of them (all of them in the Eurozone). The latest data on urban employment in state-owned enterprises (SOEs), down to around 15% from the 80% peak of 10 years ago, made me reconsider and come round to Kolodko’s view of Chinism, also supported by Milanovic (2018), for whom today’s China would warrant an ABCD score of 0001 (which in the early 2000s and Nuti 2018a I had assigned only to the German economy under Nazi rule).

The Chinese describe their economic system as “hybrid socialist market economy”. No doubt China’s economy today is not a hyper-liberal market economy, but it’s certainly a normal market economy, which, however, has retained, in its evolution, all the economic policy instruments traditionally associated with the conduct of national policy in the capitalist market economy. In his classic economic policy treatise Ian Tinbergen (1952, 1956) theorized the use of instruments such as monetary policy, for the management of the money supply and the access to and cost of credit and of the exchange rate; fiscal policy in the form of the level and structure of taxes and public expenditures, to be harmonised with monetary policy for the management of public debt; the price and investment policy of public enterprises; and finally, albeit as a last resort, the possible use of direct controls.

Tinbergen assumed an objective function of the government, which decided the weights to be assigned to different objectives, and he asserted the need to have at least as many policy instruments as the objectives to be targeted. By modelling the structure of the crucial interdependence between the macroeconomic variables of the system Tinbergen determined the area of feasible economic policy objectives, within which the government could choose. As a description of the actual process of reaching public policy choices this procedure may appear oversimplified, but its logic is faultless. From this point of view the Chinese economic system of today is undoubtedly a market economy subject to traditional economic policy instruments. In addition, however, Party organisations that exist even in private and foreign-owned companies are another tool that makes policy measures easier to enforce.

Admittedly the victory of liberalism and hyper-liberalism, ushered by the rise to power of Reagan and Thatcher in the 1980s, has pervaded most capitalist economies, with the delegation of monetary policy to independent central banks, moreover disconnected from fiscal policy; the imposition of austerity constraints on public budget deficit and debt, regardless of the cycle phases; the privatisation of public enterprises and the replacement of direct controls with market parameters. But there is no reason to consider these strategies, respectable as national economic choices, as if they were universally valid, especially at a time when their hyper-liberal foundations are subject to strong theoretical, empirical and political criticisms.

It is true that the convertibility of the Chinese currency initially remained subject to a measure of central direct manipulation of the exchange rate, which was allowed by the WTO after China’s entry among its members. Initial undervaluation was essential for the promotion of net exports, the growth of income and employment, and the enormous growth of the trade surplus of China and the consequent massive accumulation of foreign exchange reserves and a huge stock of FDI. However, the limitations of earlier incomplete liberalization of currency and credit have been greatly reduced or eliminated in modern China.

In Poland under Gierek in the 1970s, there were discussions about “parametric planning”, whereby enterprises could do what they liked but the central power would modify their parameters to the point of inducing the desired results through the manipulation of those parameters at enterprise level. But China does not correspond to “parametric planning” because it remains subject to the checks and automatic mechanisms of uniform market prices for goods and services.

The preservation of the traditional tools of economic policy—fiscal, monetary, public enterprises and direct controls—should be seen as the fundamental feature of public control on economic variables and not as the avoidance or evasion of the fundamental requirements of a market economy. Moreover China has made monetary policy more flexible (for example by reducing commercial banks’ reserve requirements), at the same time reforming and liberalizing its financial markets (so that now Chinese citizens can invest abroad up to 50 thousand dollars per person, and the yuan has been revalued repeatedly).

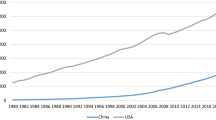

6 Chinese Achievements

China’ growth in terms of income per head has been extraordinary. In the last four decades no other economy in the world has developed faster than China: in 1979–2018 its GDP growth rate averaged 9.5% (including the poor performance of 1989–1990 following the Tiananmen Square massacre). In the recent recession of 2008–2009 the Chinese economy also did much better than many other countries, especially in the West, that experienced large output losses, while Chinese growth rates decreased only marginally—from 14% in 2007, to 10% and 9% respectively in 2008 and 2009, and increased to 10% in 2010–2011, falling very gradually to current rates of 6–7%, in line with the official target of 6.5%–7% in the current five-year plan 2016–2020.

Such growth performance was associated with a massive export drive first facilitated by the undervaluation of its currency, then consolidated by the maintenance and increase of international competitiveness thanks to its growing productivity due to technical progress and innovation, and by the containment of wage costs. The trade surplus that has been generated consistently has allowed China to amass increasing foreign currency reserves, fairly modest as a proportion of GDP (under 2%), but very large in absolute terms (second only to the German surplus, which in the last ten years has consistently exceeded the EU statutory limits of 6% of GDP). While in 2004, out of 49 SOEs listed on the Fortune Global 500, 14 were Chinese companies corresponding to 10% of their value, in 2016 in the group of 101 globally important SOEs there are as many as 76 Chinese companies corresponding to over 20% of their value (Bałtowski and Kwiatkowski 2018).

Popov (2018) attaches great importance to the “institutional capacity of the state” (to collect taxes and to constrain the shadow economy, to ensure property and contract rights, and law and order in general) in long-term economic performance and attributes the acceleration of growth in China after 1978 not only, and not as much, to economic liberalization, as to the strong institutions created by the communist party in 1949–1978. “Without these strong state institutions liberalization would probably have produced the same effects as in Latin America in the 1980s or in Sub-Sahara Africa in the 1990s or even worse—as in the former USSR in the 1990s.”

In its “New Era”, which aims to achieve a “moderately prosperous” society by 2035 and the role of a great power by 2050, China has embarked on a transformation from a model based on heavy industry, construction and exports, and a high degree of environmental pollution, to a model focused instead in the development of services and of national consumer demand (which still today represents only 40% of GDP), ecologically more responsible and desirable. Over the last 10 years, Chinese enterprises have been particularly active in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa in the promotion of investment in raw materials, especially in the extractive industries, and infrastructure to facilitate their export to China.

In 2013, President Xi Jinping announced a grandiose initiative called “One Belt One Road” (OBOR), a vast infrastructure investment program aimed at promoting trade between China and its foreign partners to the west, south and north, inserted in the Constitution of the Communist Party. The component One Belt consisted of rail routes from western China through Central Asia to Europe. The component One Road in reality entailed the development of harbours and facilities to increase traffic from East Asia and connect it to the One Belt, making a connection from Indochina to Poland in a generation, with a planned investment of about 4 trillion dollars. The program involves 65 countries in Asia, Middle East, North and East Africa, and East Central Europe (the so-called 16+1 Initiative, including 16 post-socialist countries: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia). An important role in these developments is taken by the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB, although initially grossly under-capitalised compared to the immense planned investment), with the participation of the UK as a founding member, of the World Bank and the Islamic Development Bank, but without the participation or the support of the United States.

Fukuyama (2018) sees this project as an attempt to export the Chinese model of development, by developing industrial capacity and consumer demand out of China, moving its heavy industry (and the associated environmental destruction) to developing countries at the same time stimulating demand for Chinese products. The model seems more promising than the Western strategy of promoting development through investments in health and education, support for civil society, women’s advancement and the fight against corruption. The successful export of the Chinese model would put Central Asia at the centre instead of the periphery of the global economy, and the form of authoritarian government of China would adversely affect the development of democracy in satellite economies. In 2017, the initial general support (except the United States and India) for the project One Belt One Road cooled down for fear of a new Chinese economic and perhaps even military hegemony.

7 Globalisation

Kolodko’s conjecture (2018b) that China might “save the world” relies on the notion that globalisation—of trade, capital and labour—is an irreversible process, a win-win strategy that has worldwide universal benefits. International trade liberalisation undoubtedly involves net benefits, but at the same time it inflicts losses on some of the national subjects affected. The overcompensation of losers on the part of the gainers would require international transfers that are impractical (because of the lack of global governance institutions with power of taxation and re-distribution) and/or transfers from poorer gainers to richer losers that are undesirable as they would increase inequality (Nuti 2018b). Potential overcompensation is not sufficient, it needs to be actual.

The belief that globalisation benefits everybody, a tide that lifts all boats, whose benefits in any case “trickle down” from the initial gainers to the rest of the population, is unfounded: “trickle up” is most likely (Kolodko 2002, 2004). Hence the recent drive towards protectionism and trade wars, the diffusion of Trump’s belief that “trade wars are good”, supported by a large number of Americans. The EU has a special fund to alleviate the redistributive impact of trade liberalisation, a purely token amount relatively to the US equivalent fund, which is greater but still grossly inadequate. Shiller (2018) finds that support for protectionism is due to the job insecurity that free trade often creates, which is why governments must find new ways to insure workers against the risks of a globalized market. Unless compensation provisions of some kind are provided, support for protectionism will continue.

The same considerations apply to the mobility of capital, even if we neglect the possibility of capital flowing from less developed to advanced countries, and the risk of sudden reversals of financial capital flows following changes in self-fulfilling expectations. And the same considerations apply to mass migrations of labour that are in practice unrestricted and also lead to the same redistributive problems of benefits and costs associated with other forms of globalisation.

In a world without borders the net benefit from migrations has been often overestimated, but even the more sober assessments are still appreciable: Docquier et al. (2014) estimated that liberalising migration would increase world GDP by between 7.0 and 17.9 per cent, equivalent to 11.5–12.5 percent in the medium term. But the gains of migrants and of their employers, and workers’ gains in the country of origin, cannot be tapped to overcompensate the losers, i.e. workers in the host country and employers in the origin country, without international transfers which are not feasible or transfers from the poorer to richer subjects which are undesirable. It is essential to distinguish between refugees and economic migrants, and to contain and control migratory flows within the limits of the various countries’ willingness and ability to welcome them and finance their integration—either directly or thanks to the financial contribution of countries that might prefer to pay instead of taking on an obligation to take them, which ought to be based on UN criteria. Finally, the advantages of trade liberalisation do not extend to trade agreements regulating standards, competition and jurisdictions (Rodrik 2018).

We argued earlier that the trade war started by President Trump is likely to be won by China, as the US trade deficit is bound to continue as long as the policies of fiscal deficit and excess investment over saving continue. But there is also the possibility of persistent selective trade denial on both sides, which would replicate the risks of nuclear armaments escalation and eventually might lead to Mutual Assured Destruction (though fortunately only in strictly economic terms, see Minxin 2018).

In sum, both the desirability of unrestricted globalisation, and the dynamic role of China in its diffusion, should not be taken for granted.

8 Sustainability: Economic, Social and Political

The economic and environmental sustainability of China’s growth should be enhanced by the transformation of its economy from a model based on heavy industry, construction and exports, and a high degree of environmental pollution, to a model focused instead in the development of services and of national consumer demand (which still today represents only 40% of GDP), ecologically more responsible and desirable. However, so far the conversion of the Chinese economy has been accompanied by slower and more variable development, still very creditable and respectable but slower than expected by Chinese leaders, therefore raising problems of political legitimacy and production capacity restructuring.

The sustainability of the Chinese model will depend on the capacity to address and resolve its other many challenges. First of all is the containment of inequality, including the reduction of marked differences between metropolitan and rural regions. Growing inequality has been accompanied by cultural changes that support it and justify it: Milanovic (2018) reports a successful businessman declaring that “Wealth is everything; wealthy people and wealthy countries rule, the others accommodate themselves the best they can.” This may well be the case, but this Hayekian attitude might be self-destructive. For a start, “institutional capacity” to which Popov (2018) attributes a paramount importance for the success of the Chinese model, is significantly reduced by inequality (as acknowledged by Popov 2017).

Polyakova and Taussig (2018) point out that both Xi and Putin, in their quality as long-term autocrats, have to manage “the brutal competition of the elites for loyalty and succession, and balance the growing tensions between the central government and the restless regions”, and to this end they will seek to strengthen their position at home by pursuing international policies more and more daring and risky, the failure of which could undermine their power.

Other challenges range from the reduction of private debt of companies and society (increased from 150% of annual GDP in 2008 to 250% in 2017) and the parallel containment of informal credit that circulates in the “shadow” banking system at higher interest rates but with liquidity and stability problems. Budget constraints of state enterprises need tightening, competition between SOEs and private enterprises needs to increase. The Chinese population has started ageing before reaching a high level of income (still at 30% of that of the United States), a problem that has to be addressed. Progress is required also in environment protection and reclamation, as well as in the establishment of trade union and political participation in the formulation of social and economic policies. These are formidable challenges; their economic implications can be partly cushioned off by the past accumulation of reserves by the Central Bank of China and the massive stock of property and FDI held abroad by the Chinese, but even taking these reserves into account China seems to be over-extended, domestically and internationally.

China is massively over-extended, with the OBOR continental investment plan and its financing, as well as the assistance that has been provided with aid, loans and foreign direct investment in Africa and Latin America. Chinese activities have concentrated especially in the extractive industries and in infrastructure facilitating their export to China and the penetration of Chinese exports, raising—rightly or wrongly—suspicions and fears about colonial ambitions, especially in view of its increasing military and naval power and occupation of tiny South China Sea islands to control naval routes. China is bound to suffer greatly from the trade war with the United States. Chinese foreign exchange reserves are large but will not last forever. Recent scandals, such as that involving the production of substandard vaccines,Footnote 5 have hurt the credibility of the Communist Party and the President’s standing. The constitutional change prolonging Presidential tenure beyond statutory limits, largely irrelevant because it does not affect Mr. Xi’s power as Party Secretary, is a sign of political stability but also of non-contestability of political legitimacy and authority.

Reports of increasing incidence of protest, of mounting official pressure to dispossess peasants of land especially in valuable locations, of re-education camps where actual or potential dissidents are detained, are increasingly disconcerting.

9 The Non-exportability of the Chinese Model

A frequently asked question in the last Soviet days used to be: “Could the Soviet Union realise a Chinese-style economic system?” and the standard answer was: “No, simply we do not have enough Chinese here” (the same kind of answer, in fairness, used to be given about the possible introduction of a Scandinavian system). This crude dismissive answer is much more serious than it might seem. The model is not exportable outside China, or at any rate outside Asia or the developing countries that already have a system of Weberian “political capitalism”. Other populations value too much personal freedoms, political democracy and egalitarian values for them to be willing to sacrifice them for the sake of economic gains—even if the Chinese model was sustainable in all its economic, social, political dimensions, and a fortiori when their sustainability is actually uncertain.

In conclusion, the Chinese economic system is indeed a unique system combining elements of both capitalism and socialism:

capitalism given the dominance of

-

private property and enterprise,

-

wage labour,

-

market discipline,

-

profit making and

-

inequality of income and wealth; and

socialism given

-

the residual importance of public ownership (of land, capital, strategic sectors like banks and energy) and

-

the active instruments of economic policy as well as political and administrative intervention.

The system, whether labelled as political capitalism as suggested by Milanovic or Chinism as suggested by Kolodko, has been supremely successful in the promotion of economic growth in a developing economy with a one-party political system at the cost of corruption and inequality. But it strikes an uneasy and potentially unstable balance between a Hayekian laissez-faire economy and an insulated, centralised bureaucracy. President Xi’s recently renewed anti-corruption campaign is an attempt at preventing the endemic corruption of the political and administrative spheres. This is extremely hard to do in China and probably even harder elsewhere. When the system gets quite corrupted, it ceases to produce high growth rates and its key attractiveness and rationale vanish.

The system’s success as an engine of globalisation and the desirability of globalisation itself should not be taken for granted; its economic, social and environmental sustainability are subject to considerable challenges.

Finally this Chinese model, even if successful and sustainable, is not necessarily exportable to developed countries in the West. China can probably succeed in saving itself, but its system’s suitability to “save the world” remains to be proven.

Notes

- 1.

“God is everywhere, Kolodko has already been”, people used to say.

- 2.

He used to be recognised as “The fastest among finance ministers and the best fiscal expert among marathon runners in the whole world”.

- 3.

The Chinese Statistical Office classifies property as state, collective, cooperative, joint, limited liability, share companies, private, funded by Hong Kong Macao and Taiwan, foreign, and self-employed (Kolodko 2018a). No wonder the division between private and public sectors is blurred.

- 4.

A finer classification, involving even only one additional intermediate value between 0 and 1, or an additional component, would multiply the number of possible systems respectively to 81 and 32, most of which are not representing any actual or even utopic system.

- 5.

In August 2018 China experienced its “worst public health crisis in years” (“Editorial: Vaccine scandal and confidence crisis in China”, The Lancet, 392(10145), August 2018, p. 360). The Chinese vaccine maker Changsheng Biotechnology was found to have falsified records and produced substandard vaccines against rabies, diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (DPT), which were administered to 215,184 Chinese children. Another 400,520 substandard DPT vaccines had been produced by the Wuhan Institute of Biological Products and had been sold in Hebei and Chongqing. On July 25, China’s drug regulator launched an investigation into all vaccine producers across the country. 15 people from Changsheng Biotechnology, including the chairman, have been detained by Chinese authorities.

References

Bałtowski, M. and Kwiatkowski, G. (2018): Przedsiębiorstwa państwowe we współczesnej gospo- darce (State Enterprises in the Modern Economy). Warsawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe

PWN. Berthold, R. (2017): About the 19th National Congress of the CPC. China Today, November.

Blair, T. and Schroeder, G. (1999): The Way Forward for Europe’s Social Democrats, A Proposal. Working Document, Labour Party, London.

Coase, R. and Wang, N. (2012): How China Became Capitalist. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Coase, R. and Wang, N. (2015): How China Became Capitalist. Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, BBL Seminars, Tokyo University, 17 September.

Docquier, F., Machado, J. and Sekkat, K. (2014): Efficiency Gains from Liberalizing Labor Mobility. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 117(2): 303–346.

Fukuyama, F. (2018): Exporting the Chinese Model. Project Syndicate, 12 January.

Kolodko, G. W. (2002): Globalization and Catching-up in Transition Economies. Rochester University Press.

Kolodko, G. W. (2004): Institutions, Policies and Growth. Rivista di Politica Economica, May–June: 45–79.

Kolodko, G. W. (2018a): Socialism, Capitalism or Chinism? Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 51(4): 285–298.

Kolodko, G. W. (2018b): Czy Chiny zbawią świat? (Will China Save the World?). Prószyński i S-ka, Warsaw. (English edition forthcoming as China and the Future of Globalisation, I. B. Tauris-Bloomsbury, 2019.)

Kornai, J. (1980a): The Economics of Shortage. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Kornai, J. (1980b): ‘Hard’ and ‘Soft’ Budget Constraint. Acta Oeconomica, 25(3–4): 231–246.

Kornai, J. (2013): Dynamism, Rivalry and the Surplus Economy—Two Essays on the Nature of Capitalism. Oxford University Press.

Kornai, J. (2016): The System Paradigm Revisited Clarification and Additions in the Light of Experiences in the Post-Socialist Countries. Acta Oeconomica, 66(4): 347–569.

Milanovic, B. (2018): Hayekian Communism. Globalinequality Blog, 24 September, http://glineq.blogspot.com/2018/09/hayekian-communism.html.

Milanovic, B. (2019): Capitalism Alone. Harvard University Press (forthcoming).

Minxin, P. (2018): MAD about Sino-American Trade. Project Syndicate, 20 September.

Naughton, B. and Tsai, K. (eds) (2015): State Capitalism, Institutional Adaptation, and the Chinese Miracle. Cambridge University Press.

Nuti, D. M. (2018a): The Rise and Fall of Socialism. Dialogue of Civilizations (DOC) Research Institute, Berlin, https://doc-research.org/2018/05/rise_and_fall_of_socialism/.

Nuti, D. M. (2018b): The Rise, Fall and Future of Socialism. Social Europe, 25 and 26 September, https://www.socialeurope.eu/the-rise-fall-and-future-of-socialism-1, https://www.socialeurope.eu/the-rise-fall-and-future-of-socialism-2.

Polyakova, A. and Taussig, T. (2018): The Autocrat’s Achilles Heel. Brookings, 5 February.

Popov, V. (2017): Socialism is Dead, Long Live Socialism! Dialogue of Civilizations (DOC) Research Institute, Berlin, http://pages.nes.ru/vpopov/documents/SOCIALIM%20IS%20DEAD-WP.pdf.

Popov, V. (2018): Mixed Fortunes: An Economic History of China, Russia, and the West. Oxford University Press.

Rodrik, D. (2018): The Great Globalisation Lie. Prospect, January: 30–34.

Shiller, J. R. (2018): How to Protect Workers without Trade Tariffs. Project Syndicate, 17 July.

Tinbergen, J. (1952): On the Theory of Economic Policy. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Tinbergen, J. (1956): Economic Policy, Principles and Design. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Weber, M. (1904a): The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge.

Weber, M. (1904b): The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated with an Introduction by Parsons, T., London: Routledge, reprinted 1992, https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/podzim2013/SOC571E/um/_Routledge_Classics___Max_Weber-The_Protestant_Ethic_and_the_Spirit_of_Capitalism__Routledge_Classics_-Routledge__2001_.pdf.

Weber, M. (1922): Economy and Society. California and Berkley: University Press, https://ia600305.us.archive.org/25/items/MaxWeberEconomyAndSociety/MaxWeberEconomyAndSociety.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Nuti, D.M. (2023). The Chinese Alternative. In: Estrin, S., Uvalic, M. (eds) Collected Works of Domenico Mario Nuti, Volume II . Studies in Economic Transition. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23167-4_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23167-4_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-23166-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-23167-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)