Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had sweeping effects that have disrupted almost every part of society worldwide. In this chapter, we discuss the psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. We begin with a review of psychological distress and psychiatric symptoms arising with the onset of the pandemic, focusing on the general population as well as specific groups such as children, students, parents, medical providers, essential workers, and disadvantaged populations, among others. We then evaluate the potential impact of the pandemic on suicide and how patterns of adverse psychiatric effects have varied over time. We also provide a comprehensive overview of both risk and protective factors for psychological distress and psychiatric disorders during the pandemic. After a discussion of psychiatric manifestations and sequelae reported in those affected by COVID-19, we conclude with an exploration of putative strategies to promote mental health in a world with COVID-19.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The burden of infectious disease and consequent mortality brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic is paralleled only by the pervasive effects the pandemic has had on global mental health. For too many reasons, there have and will continue to be adverse psychological and psychiatric effects of the pandemic. With each of the approximately five million deaths that have occurred globally thus far, there are the family and loved ones left behind to grieve. For those who survive COVID-19, the trauma can have lasting impacts. And for individuals throughout the world, all are forced to continue adapting to uncertain and often highly dangerous circumstances.

This chapter focuses on the psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. We begin with the acute effects of the pandemic in substantially increasing rates of psychological distress and symptoms of psychiatric disorders. Throughout, we highlight broad findings from the general population as well as sub-group-specific impacts on those of different ages, genders, races and ethnicities, familial roles, and occupations, among others. We next explore both risk and protective factors for psychological distress and psychopathology during the pandemic. We also provide an overview the psychiatric manifestations and sequelae of COVID-19 itself, exploring potential psychological and pathophysiological mechanisms. We conclude with promising coping and psychological adaptation strategies, drawing from evidence reported during prior pandemics as well as early data reported during the ongoing pandemic. It is hoped that lessons learned from history and our collective current struggle can inform approaches to not only cope with the pandemic but emerge more resilient than before it.

Psychological and Psychiatric Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The initial onset of the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated fear and psychological distress worldwide. This section describes results from numerous countries documenting heightened psychiatric symptoms and psychological distress beginning with large, nationally and regionally representative prevalence rates. We then highlight adverse psychological and psychiatric effects on specific subgroups of people defined by sociodemographic, familial, and occupational characteristics. Subsequently, we cover the complexities of whether the pandemic has affected suicide, distinguishing between suicidal ideation, self-injurious behavior, and completed suicides. Having provided snapshot estimates, we finally overview important evidence that changes in mental health have been heterogenous within overall populations, showing several patterns of change—or lack thereof—that vary over time.

General Population-Based Estimates of COVID-19-Related Psychiatric Symptoms and Psychological Distress

In one of the first nationally representative surveys out of China, almost 35% of individuals reported psychological distress with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic [1]. This finding was consistent with sentiment analyses of posts on the social media platform Weibo, which found psychological indices of depression, anxiety, indignation, and sensitivity to social risks increased while indices of happiness and life satisfaction decreased [2]. During the initial outbreak in Wuhan, the prevalence of depression was 48% and anxiety was 22.6%, and 19% had both depression and anxiety [3]. Furthermore, an estimated 7% of Wuhan adults had significant symptoms of post-traumatic stress [4]. Over half of residents in the Liaoning Providence reported feeling apprehensive and horrified due to the pandemic [5]. In Hong Kong, 19% and 14% of adults met threshold criteria for depression and anxiety, respectively, and approximately 25% reported that their mental health had deteriorated since the onset of the pandemic [6]. These data demonstrated clearly the adverse effects on mental health that had arisen in the acute onset of the pandemic and served as indicators of what was to come in other parts of the world.

Studies from the USA emerged soon after the first case of COVID-19 was reported in January of 2020. As in China, nationwide social media content reflected significant distress with the onset of the pandemic. A sentiment analysis database of U.S. Twitter posts termed the “Hedonometer” [7] showed that overall indicators of happiness dropped precipitously, with the lowest period from May 26th to June 9th [8]. In parallel, estimates of depression prevalence rates were threefold higher among U.S. adults during the beginning of the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic periods [9]. Data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicated that, beginning in April and persisting through July of 2020, about 30% of adults nationwide reported symptoms of anxiety and 25% reported symptoms of depression [10]. These estimates are markedly higher than those reported by the CDC in 2019, when 8.1% and 6.5% of adults had symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively [11]. In June of 2020, an estimated 26% of adults were experiencing symptoms of stress- and trauma-related disorders due to the pandemic, and just over 13% of adults reported either starting or increasing their use of substances in order to cope with stress and difficult emotions related to the pandemic [12].

In the United Kingdom, rates of anxiety nearly doubled, increasing from 13% pre-pandemic to 24%, while estimates of depression remained constant [13]. 21% and 19%, respectively, of Austrian citizens met or exceeded threshold criteria for depression and anxiety, and 16% reported experiencing clinical insomnia [14]. During the first week of the government-mandated shutdown from March 13th to 18th, 35.6% of Italian adults had clinically significant levels of distress, with 29% experiencing symptoms of post-traumatic stress; symptoms of depression and anxiety were reported by 37.8% and 51.1%, respectively [15]. A nationally representative study found that 64% and 53% of adults in Cyprus reported above-minimal symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively, and that two-thirds felt they had experienced a decreased quality of life due to the pandemic [16]. Data from Jordan indicated that, in March of 2020, 23% of the population had depression and 13% had anxiety [17]. Overall, a comprehensive meta-analysis of all studies ascertaining prevalence rates of depression and anxiety throughout the world in 2020 found that the pandemic contributed to an additional 53.2 million cases of major depressive disorder and 76.2 million additional cases of anxiety disorders globally, representing increases of 27.6% and 25.6%, respectively [18]. In sum, these findings indicate clearly that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to markedly high rates of psychological distress and psychopathology globally.

Distress and Psychiatric Symptoms Among Specific Sociodemographic Groups

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacted differential impacts on various groups based on sociodemographic, familial, and occupational factors. In this section, we provide an overview of results documenting rates of psychological distress and psychopathology among subgroups of individuals defined by age, gender, education, occupational status, and racial/ethnic minority group. Here, our aim is to provide only descriptive results among these various subgroups; evidence for potential demographic, occupational, and clinical risk factors for COVID-19-related distress and psychiatric symptoms is covered in section “Risk and Protective Factors for Psychological Distress and Psychiatric Illness During the COVID-19 Pandemic”.

Children and Adolescents

Substantial concerns have been raised about the potential impact of the pandemic on children and adolescents due to the limitations in social interaction, reduced access to school and educational resources, and intrafamilial discord [19, 20, 25, 36, 37]. In tandem, the tragic deaths of parents and other caregivers have caused unimaginable devastation to children throughout the world, as more than 1.5 million have lost primary or secondary caregivers globally [21]. Lockdown orders and school closures have left children in a mentally vulnerable position, as elevated rates of depression and anxiety have been noted in children as young as 6 years old [40]. In adolescents, pandemic-era rates of anxiety and depression were reported to be approximately 12% and 19%, respectively [22]. As of March 2021, estimates of the global prevalence rates of depression and anxiety among children and adolescents were 25.2% (depression) and 20.5% (anxiety) [37], increased from earlier estimated rates of ~10–15% (e.g., [24]).

Disruption in daily routines, social interaction, and education have contributed significantly to the increased burden of distress and psychiatric conditions among youths. Digital education was found to be exhausting for many children, potentially impacting future scholarly performance [24]. Evidence exists showing disruptions in sleep-wakefulness patterns among children overall, with potentially greater impact on children with neurodevelopmental conditions [29]. Distance learning may be particularly challenging for children with ADHD [26, 27]. Of note, children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or poor emotion regulation before COVID-19 appear to suffer from greater exacerbations on mental health during the pandemic [36].

For both children and adolescents, it is still unclear what the long-lasting effects of the drastic reduction in physical activities on mental and physical health will be [32]. Early data show clearly negative effects: a large cross-sectional survey of children (ages 6–10 years) and adolescents (ages 11–17 years) found associations between lower physical activity, higher screen time, and greater mental health symptoms [33]. The heightened adverse effects on the mental health of children and adolescents with ADHD varies strongly by whether or not ADHD children participate in sports [211], suggesting particularly negative impacts of stay-at-home/shelter-in-place orders on children with ADHD.

Familial discord due to stay-at-home orders, pandemic-related stress, and increased demands of online education have also contributed directly to distress among youth. Studies have found that increased familial quarrels have led to increased psychological distress in adolescents during COVID-19 [30, 31]. A direct, positive relationship has been documented between children’s COVID-19-related fear and levels of parental anxiety, suggesting the possibility of self-reinforcing patterns of distress in the parent-child relationship [28]. Of particularly grave concern is the risk of increased child abuse in the context of these stressors, coupled with decreased contacts with mandated reporters. In the USA, the CDC reported that the proportion of emergency department (ED) visits related to child neglect and abuse that results in hospitalization increased despite an overall decrease in the number of such ED visits [35]. These data suggest that the severity of child abuse has worsened and/or that only the most severe cases are brought to medical attention. An independent study found that ED visits for suspected child abuse or neglect increased from March to October of 2020 compared to rates from the same period of time in 2019 [81]. Overall rates child and adolescent discharge from the ED for assault and maltreatment were lower in Ontario than pre-pandemic levels, but it is unclear if there were changes in the severity of injuries documented [34]. Alarmingly, the rates of children ages 0–5 years admitted to the hospital for physical abuse increased substantially in a French study [35]. For these reasons, it appears that children may be at increased risk of harm and mistreatment during the pandemic, although much further study and monitoring is warranted considering the severe negative consequences that abuse and neglect have on children’s mental health.

Students and Young Adults

Numerous studies have examined the psychological impacts of the pandemic on students and young adults. In the U.S., available evidence indicates high levels of psychopathology, with 43.3% of young adults having depression, 45.4% having anxiety, and 31.8% having PTSD symptoms; furthermore, 61.5% reported feelings of loneliness [38]. These findings are aligned with results from studies of students in undergraduate, graduate, and professional school settings. Estimates of anxiety and depression among college students in the Guangdong Providence of China were 26.60% and 21.16%, respectively [42]. Among Chinese college students quarantined at home, prevalence rates of PTSD and depression were found to be 2.7% and 9.0%, respectively. Data from Ukraine indicated that 24% of college students met criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and 32% met criteria for depression [43]. A longitudinal study of U.K. college psychology students found that one-third could be classified as having clinical depression at the time of lockdown compared to 15% at baseline and that this rise in depression strongly correlated with worsened sleep quality and a shift toward a later sleep and wake time [41]. Increased consumption of alcohol and other drugs may contribute to these findings, as a study of US college students found that, compared to pre-lockdown levels, rates of alcohol and cannabis use increased by 13% and 24%, respectively [39]. Furthermore, a smartphone-based study found increased levels of sedentary behavior, anxiety, and depression among college students compared to previous term periods in a manner that correlated positively with COVID-19-related media consumption [40]. Across 40 U.S. medical schools, 24.3% of students were depressed and 30.6% had anxiety [44]. Comparable estimates were found among nursing students, with 38.8% and 37.4% had anxiety and depression, respectively [45]. Overall, the pandemic has had sweeping negative impacts on young adult students, in part due to the heightened vulnerability of younger individuals to COVID-19-related distress and psychiatric conditions (discussed below).

Frontline Healthcare Workers

The pandemic has placed a burden on frontline healthcare workers that is unprecedented in recent history. Early in the course of the pandemic, several reports documented increased symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and stress among those working in medical occupations. More than half of healthcare workers in Wuhan self-reported severe levels of perceived stress during the first few months of the pandemic [47] and greater than 50% in Chinese hospitals overall reported symptoms of depression and distress [48]. Medical workers, compared to non-medical workers, had higher rates of insomnia, depression, anxiety, somatization, and OCD symptoms in the early stages of the pandemic [49]. Estimates of more clinically severe depression, anxiety, stress, and psychological distress were 5.3%, 8.7%, 2.2%, and 3.8%, respectively [50]. Nurses in Hubei, China, were found to have a 16.83% incidence of PTSD in the context of the pandemic 16.83% [51]. In parallel, there has been a precipitous decline in workplace satisfaction among essential healthcare workers; one study reported that the proportion of those working in an obstetric hospital who were at least somewhat satisfied with their job declined from 93% pre-pandemic to 62% after it began and that the rates of anxiety related to their responsibilities increased substantially [52]. Overall, meta-analytic results suggest that the estimated rates of depression and anxiety among healthcare workers to be ~20% [53], indicating a substantial burden of psychopathology.

Other Essential Workers

Essential workers in occupations such as maintenance, retail, grocery, cleaning, and law enforcement, among others, were largely exempted from social distancing measures that required most others to work from home. Not surprisingly, the comparatively higher levels of potential exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection and increased workplace demands have negatively impacted the mental health of these individuals. Fear of contracting and spreading the virus have significantly increased worker’s overall stress during the pandemic [12]. Surveys taken during the pandemic discovered that essential workers are more likely to report symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorders (42% vs. 30%), starting or increasing substance use (25% vs. 11%), and suicidal thoughts (22% vs. 8%) than non-essential workers [54]. The American Psychological Association’s ongoing Stress in America research revealed that 29% of essential workers in 2020 reported that their mental health had deteriorated since the pandemic and that more than half have been relying on self-reported unhealthy habits to get through the pandemic, including 39% of workers who reported drinking more alcohol [55]. This same report also found that essential workers were more than twice as likely to have been diagnosed with a psychiatric condition since the pandemic began compared to those who were not essential workers (25% vs. 9%) [55]. Consistent with these findings are those from an online survey-based study of essential workers in Brazil and Spain which found that 27.4% had both anxiety and depression, 8.3% had depression alone, and 11.6% had anxiety alone [56]. Data from Australia indicated that non-medical essential workers had higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress and lower quality of life than both the general population and essential workers in healthcare [57]. Among retail grocery store workers during the pandemic, the point prevalence of anxiety and depression were estimated to be 24% and 8%, respectively [58]. Without a doubt, the societal burdens placed on those working in these occupations has come at the cost of significant psychiatric morbidity and distress.

Parents

Parents and primary caregivers of children face additional disruption and daily stressors due to the sudden and massive shift to online learning platforms as education systems worldwide enforced social distancing measures. Thus far, data on parental perceptions of online education indicate general dissatisfaction and increased stress as well as a perception that teachers were expecting too much from them [59]. Furthermore, childcare has been cited as a leading cause for concern among parents in the USA [60]. These findings parallel survey-based research showing that an overwhelming majority of parents agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic made the 2019–2020 school year extremely stressful for them, especially among those with children ages 8–12 [61]. The challenges with childhood online education have been accompanied by increased symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders among parents, as 47% of mothers and 30% of fathers who had children at home for remote education said that their mental health had worsened [62]. In parallel, half of all U.S. parents reported increased levels of stress compared to their pre-pandemic levels; this figure rose to 62% for parents with children at home engaged in remote learning [61]. Following the closure of schools, almost a quarter of caregivers reported anger and agitation, with over a third also noting anxiety stress and loneliness, suggesting up to a fourfold increase in psychiatric symptoms [63]. Similarly, Czeisler et al. identified more substance use (32.9%) and suicidal ideation (30.7%) among primary caregivers [12]. A longitudinal study of Canadian mothers found that within-subjects depression and anxiety scores increased by a mean of 2.3 and 1.04 points, respectively, and that one-third experienced clinically significant levels of depression and anxiety at the COVID-19 time point; these rates were higher than those observed at previous time points in the 8-year study period [64]. Parental stress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic may be even higher among caregivers of children with neurodevelopmental disorders and disabilities [65], a phenomenon that may vary with the mental health status of caregivers themselves, with low-mental-health caregivers experiencing even higher rates of increased psychological distress [66]. In a study of over 500 Portuguese mothers who gave birth to infants aged 0–12 months either before or during the pandemic, 27.5% of mothers overall had clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety; furthermore, mothers who gave birth during the pandemic were found to have signs of decreased emotional awareness of their children and more impaired infant-mother bonding [67]. Although not surprising, these findings highlight the tremendous impact the pandemic has had on parents throughout the world.

Pregnant Individuals

Pregnant individuals have had to confront heightened uncertainty during the pandemic due to worries about their health and that of their pregnancies, combined with restrictions to healthcare access resulting from social-distancing measures [68]. High rates of post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression have been documented in pregnant mothers during the pandemic, with worries associated with their pregnancies, delivery plans, family presence during and after the birthing process, and exposure of the fetus to COVID-19 cited as the top concerns [69]. Additional studies have found that about one-third of pregnant women reported elevated symptoms of depression [70] and that expected mothers had higher increases in depression, anxiety, and negative affect than non-pregnant women [71]. In contrast, however, a study in China found that pregnant women had lower overall rates of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and PTSD than non-pregnant women [72]. A study of routine, prenatal urinalysis screens in a large Californian healthcare-delivery system found a 25% increase in the proportion of expectant mothers using cannabis during their pregnancies [73]. Perhaps not surprisingly, a large, representative survey-based study of mothers in New York City found that about half of mothers who had been trying to become pregnant before the pandemic ceased trying with the pandemic’s onset; importantly, ~43% of those who stopped trying to become pregnant reported that they would not resume after the pandemic, suggestive of potential negative perceptions of longer-term futures families in general and mothers and their children in particular [74]. Thus, the preponderance of existing data shows high rates of distress and psychiatric symptoms among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Members of Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups

Individuals belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups have seen disproportionately higher adverse mental health consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, non-Hispanic Black adults (48%) and Hispanic or Latino adults (46%) were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorders than Non-Hispanic White adults (41%) [12]. Similarly, Hispanic individuals have reported higher prevalence of COVID-19–related trauma symptoms, increased substance use, and suicidal ideation than non-Hispanic Whites or non-Hispanic Asian individuals. Those identifying as Black reported increased substance use and serious consideration of suicide in the previous 30 days more commonly than White and Asian respondents [12]. In 2020, Hispanic Americans had the highest levels of self-reported disruptions in sleep, and Black Americans were the most likely to report concerns about the future. Black and Hispanic children were found to be more likely to suffer adverse mental health effects of remove versus in-person learning [77]. As discussed below, rates of suicide have increased among Black residents in some states [76, 77]. In the U.S. overall, rates of overdose-related cardiac arrest events recorded by emergency medical services increased by ~40% in the initial months of the pandemic, but the highest increases were found among Latinx (49.7%) and Black or African American (50.3%) individuals [79]. Worse still, people of color have historically faced challenges accessing mental health care, and such barriers have likely only increased during the pandemic [76]. For these reasons, expanded access to mental healthcare resources and community-driven research efforts to evaluate potential approaches to reducing these disparities are sorely needed.

We turn now to a critical evaluation of the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on levels of suicide throughout the world.

Suicidality

With the enormous increase in depression, anxiety, trauma, and distress globally, there remains much concern about a parallel increase in suicide. Although the number of individuals with suicidal ideation and passive death wishes has clearly grown, it is unclear if rates of completed suicide have increased in the population overall. Instead, where changes have been reported, they seem specific to certain sub-groups of people and also vary in the direction of change. Here, we discuss the current state of the evidence, making the important distinction between suicidal ideation, self-injurious behaviors and suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

Many studies have estimated rates of suicidal ideation from several countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Assessment of trends in Google searches using terms indicative of users searching for suicide techniques found evidence that these searches were in fact lower than expected during the first month of the pandemic, even though there was an increase in searches related to help-seeking behavior and mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and loneliness [82]. In the USA, a nationally representative study found that 10.7% of adults reported seriously considering suicide in 2020, more than double a previous estimate from 2018 [80], with greater increases among Hispanic and Black Americans, essential workers, and unpaid caregivers for adults [83]. Similarly, a Canadian study found that there was an increase in passive suicidal ideation among the general population and especially among participants who were young, Indigenous, unemployed, single, and with pre-existing psychiatric conditions [84]. In contrast, a prospective cohort study of U.S. military veterans found a decrease in rates of suicidal ideation rates from November 2019 to December 2020 [85]. With the widespread surge in depression overall, it is generally not surprising that rates of suicidal ideation have increased, as it is a core symptom of the disorder.

In the case of self-harming behavior and suicide attempts, the picture appears more complicated. Data from over 1600 primary care clinic electronic health record systems indicated substantial decreases in the number of recorded instances of self-harm during the first several months of the pandemic; this may have been due to limited availability of on-site primary care, as this difference normalized by September of 2020 [86]. Among youths aged 13–17, there was an initial decrease in the incidence rates of suicide-related ED visits in the first 3 months of the pandemic, potentially due to stay-at-home orders and shifting needs in healthcare utilization [87]. After May, however, the overall rates returned to pre-pandemic levels observed during the summer months, and female youths had higher rates from June to December of 2020 compared to the same periods of time in 2019 [87]. Analysis of about 190 million US ED encounters found increased visit rates for suicide attempts as well as drug overdoses in March to October of 2020 compared to the same months in the year prior [36]. In contrast, a large study of Sri Lankan individuals found a 32% decrease in hospital presentations for intentional self-poisonings [88] in data analyzed from January 1st, 2019 to August 31st, 2020.

Finally, any changes in the levels of completed suicide appear to be specific to certain demographic groups and locations. An interrupted time-series analysis of data from an Australian register did not find evidence that rates of suicide increased during the first 7 months after Queensland proclaimed a public health emergency due to the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic estimates [93]. A similar analytic approach was used in a study that found no increase in rates of suicide across 21 middle- and upper-income countries from April to July of 2020; in fact, expected rates were lower than expected in some areas examined [94]. Data from Massachusetts did not find increased suicides during the initial stay-at-home orders from March to May of 2020 [89]. However, results from a Maryland study indicated an increase in suicide among Black residents during the first few months of the pandemic, while the rate among White residents decreased in the same period of time [90]. Similar results were found in a study comparing suicide rates among White and non-White residents of Connecticut [91]. Importantly, this took place in the context of already increasing suicide rates among Black and Asian or Pacific Islander Americans beginning in 2014 and continuing to 2019, with rates increasing by 30% for Black Americans and 16% for Asian or Pacific Islander Americans during that time period [92]. A comprehensive study of monthly suicide rates in Japan found that while suicide slightly decreased in the first 5 months of the pandemic, there was a sharp increase during the second outbreak from July to October of 2020, particularly among females, children, and adolescents [95]. These findings were corroborated by a separate study reporting that monthly suicide rates in 2020 compared to the same months in years prior did not increase until July (and including every month through November) for women and October (and through November) for men [93]. These important results indicate clearly that the mental health effects of the pandemic change over time with increasing durations of isolation, lock-down and social distancing-measures, and outbreaks.

Heterogeneity and Temporal Variability of Adverse Psychiatric Effects Associated with the COVID-19 Pandemic

As suggested from above discussion on suicidality, new and exacerbated psychiatric symptoms and disorders have varied through time and affect subgroups of individuals within populations in a heterogenous manner. The most convincing evidence comes from a large longitudinal study in the U.K. that identified different trajectories of mental health-related symptoms during the pandemic over time [100]. Using latent class analysis, investigators uncovered five broad patterns of temporal change in psychological health and symptoms which varied by baseline level of psychopathology at the onset of the pandemic, the direction of change in symptoms (increase or decrease), and the stability of symptoms over time. These findings have been generally consistent with those from other studies as well [96,97,−98], further demonstrating that the psychological wellbeing of individuals has not been uniformly impacted by the pandemic. Instead, there appear to be those who are resilient to adverse psychological effects, those whose level of symptoms remained constant, and even some who appeared to improve during the pandemic. These data have yielded crucial insights into risk and protective factors for distress and psychopathology during the pandemic, as explored in the section that follows.

Risk and Protective Factors for Psychological Distress and Psychiatric Illness During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The previous section provided a description of the pandemic’s adverse effects on the mental health of the general population and specific subgroups of people. We now review existing evidence of differential psychological and psychiatric impacts of the pandemic that may reflect risk or protective factors.

Potential Risk Factors for Increased Distress and Psychopathology in the COVID-19 Pandemic

Younger Age

Numerous studies have documented associations between younger age and increased risk of psychopathology and general distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. The longitudinal UK study mentioned immediately above found that although psychiatric symptoms increased above pre-pandemic levels across the entire population, this spike was the most pronounced in those ages 16–24; furthermore, those in one trajectory characterized by consistently good mental health were more likely to be 45 years or older, while those in another trajectory characterized by deteriorating mental health were more likely to be ages 16–35 [100]. Higher rates of depression and anxiety among younger adults were also reported in an additional longitudinal study in the U.K. [13]. Increased psychological distress was documented among younger Chinese individuals during the early months of the pandemic [101, 102], and student status was associated with higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety during the initial outbreak in China [104]. These findings are consistent with nationally representative data from Cyprus finding that young adults aged 18–29 reported higher levels of depression and anxiety than did those in other age groups [16]. During the initial lockdown period in Italy, older age was found to be associated with lower risk of PTSD [15].

In the USA, individuals aged 18–23 had the highest average level of self-reported stress in 2020, followed by those ages 24–41, and those in this age range had the greatest overall increases in stress from years prior [61]. In 2021, people ages 18–23 were the most likely to state that their mental health had worsened due to the COVID-19 pandemic [62], and compared to all adults, young adults were more likely to report substance use (25% vs. 13%) and suicidal thoughts (26% vs. 11%) [103]. Younger individuals in the USA experienced higher rates of anxiety and depression in the first few months of the pandemic compared to older individuals [106]. College students, in particular, may be heavily impacted, as about half of students self-reported enhanced psychologic distress is a study from a large Northeastern U.S. university [105]. A Japanese study found that rates of internet gaming disorder increased overall during the pandemic but that individuals younger than 30 years old were at heightened risk [107]. Although robust statistical models of the impacts social distancing and lock-down measures demonstrate clear benefit of these interventions on reducing risk of Sars-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19-related hospitalization and mortality (e.g., [108]), these measures have unintended adverse impacts on mental health: analyses from a nationally representative sample found that the mental health of U.S. young adults (ages 18–34) was more negatively impacted by social distancing, lockdowns, and quarantine measures [109].

Importantly, however, not all studies report a simple, linear relationship between age and adverse psychological impacts. For example, during the onset of the pandemic, Chinese individuals younger than 18 experienced the lowest levels of distress while those between ages 18 and 30 or above 60 years of age had the highest distress levels [1]. Additionally, it appears that older healthcare providers were more likely than younger ones to experience symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression [50]. Overall, however, a meta-analysis of studies throughout the world found that younger age was indeed associated with greater increases in the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders [18]. Undoubtedly, understanding of the additional factors mediating relationships between age and pandemic-associated distress and psychopathology remain incomplete and are a target of active investigation.

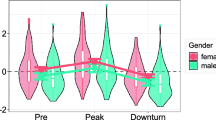

Female Sex/Gender

Both in the general population and among particular subgroups, several studies have documented elevated levels of distress in females [110,111,112], albeit with conflicting results and a lack of clarity about whether sex or gender was the variable under study. In one of the earliest nationwide reports, Chinese females had higher levels of distress than males ([1], although this was not found in a separate study [101]). Another group reported that males, rather than females, had higher overall scores on the stress, depression, and anxiety subscales of the depression, anxiety, and stress scale [104]. Female gender was also found to be the leading risk factor for symptoms of depression and anxiety among Chinese high school students [46]. For symptoms of post-traumatic stress, women reported greater symptoms than did men 1 month after the onset of the pandemic in China [4]. Among those who had been hospitalized for COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, female sex was associated with higher risk of prolonged fatigue 1 year after discharge [113]. In the Jordanian population, females were at the highest risk of depression and anxiety [17]. Similarly, Italian females were more likely to meet criteria for PTSD during the initial lockdown [15]. An Israeli study also found that women experienced higher rates of emotional distress during the pandemic than did men [114].

Female individuals from a longitudinal study in the U.K. were less likely to have a mental health trajectory characterized by consistently good mental health both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and more likely to follow trajectories of deteriorating mental health throughout the pandemic or consistently poor before and after it [100]. Of note, the same study found a greater proportion of females in a trajectory characterized by an initial decline in mental health followed by a recovery as the pandemic progressed [94]. In the USA, while men are more likely to report COVID-19 related substance use disorder and insomnia, women had higher rates of anxiety and depression [103] From a peak in April of 2020, rates of depression and anxiety declined overall, but began and remained elevated among female participants in a large US study [106]. Female sex was a leading risk factor for increased rates of positive depression and suicide screens among adolescents in a primary care setting, with a 34% increase in the proportion of female adolescents reporting suicide thoughts in the latter half of 2020 compared to the same time period in the year prior [23].

Higher rates of psychological distress were reported among female college students compared to male college students [105]. Female gender was associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety in both medical [44] and nursing [45] schools. In the medical profession, female healthcare workers had higher rates of depression, anxiety, OCD, somatic symptoms, and insomnia than did their male counterparts [49]. Compared to male nurses, female nurses were reported to be at greater risk of PTSD [51], and this is consistent with findings from a meta-analysis of psychological risk factors among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic [53].

Socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic, cultural factors, and the responsibilities of raising children have likely influenced these disparities. Many early-career women were responsible for both consistent job performance and childcare [116, 117]. As discussed previously, pregnant women faced additional stressors, such as concerns over prenatal care, fetal health, and quality of delivery procedures in a limited hospital environment [68]. Internationally, high levels of post-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety have been documented among pregnant women [69]. Compared to men with children, women with children (49%) are more likely to report symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorder than men with children (40%) [28]. Additionally, women were exposed to an elevated risk of domestic violence due to forced co-habitation with their partners during stay-at-home orders [118, 119].

Overall, a global meta-analysis found a much greater increase in the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders among females than in males [18]. Among children and adolescents, global estimates of depression and anxiety were also found to be higher in girls than in boys [45]. Moving beyond broad point estimates, however, shows a complex pattern of associations between sex/gender and risk of psychological distress and psychopathology that is likely influenced by familial and occupational roles, clinical factors, and pre-existing socioeconomic challenges.

Pre-existing Psychiatric Conditions

Cross-culturally, the mental health of individuals with psychiatric conditions has been negatively affected by the pandemic, and emerging data suggest that pre-existing psychopathology may be independently associated with additional psychopathology. During the peak of pandemic-related lockdown measures in China, those with a pre-existing psychiatric disorder experienced the pandemic as more stressful overall and had a higher magnitude of depressive and anxious symptoms than those without psychiatric conditions; of note, more than one-third of those with a mental health disorder were estimated to meet full criteria for PTSD [120]. In the early months of the pandemic, substance use was associated with higher risk of both depression and anxiety among Chinese adults [102]. Indeed, individuals with pre-existing anxiety disorders reported higher COVID-related stress and self-isolation distress than those without prior mental health diagnoses [121]. Not surprisingly, those with mood and anxiety disorders had much higher rates of anxious and depressive symptoms, and this remained throughout the first 10 weeks of the pandemic beginning in early April of 2020, despite a general decline from peak levels overall [106].

Of note, patients with affective disorders fared worse than those with psychotic disorders due to increases in perceived loneliness/social restrictions [122]. Within inpatient psychiatry patient populations, those with affective disorders, as opposed to those suffering from substance use disorder or schizophrenia, also demonstrated substantially elevated stress [124]. The pandemic has also been associated with reduced inpatient admissions to psychiatric wards, as well as increased suicidality—two observations that may very well be related [125, 126]. Among those with schizophrenia, social anxiety is associated with even higher rates of COVID-19-related psychological distress and sleep disturbance [117]. In a study of Spanish psychiatric patients, depressive and negative psychotic-like symptom domains were specifically associated with greater risk of moderate to severe neurocognitive impairment [130]. Our group also found further elevations in stress and psychiatric symptoms in an underserved minority patient population at an outpatient psychiatry clinic [123].

Most convincingly, those with a pre-existing mental illness were more likely to follow a trajectory of deteriorating mental health in a longitudinal study during the COVID-19 pandemic [100]. An analysis of 12 longitudinal studies from the U.K. found that those with higher levels of psychological distress before the pandemic were at greater risk of significant life disruptions in housing, employment, and access to healthcare [128], directly supporting the hypothesis that those with pre-existing psychological struggles were more likely to experience major negative impacts of the pandemic, all of which are contributors to further exacerbations in psychological distress.

There is now robust evidence that pre-existing psychiatric conditions also place individuals at higher risk for negative outcomes from COVID-19; as discussed below, the psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 may in turn exacerbate existing mental health disorders and precipitate new ones. Psychiatric conditions overall, especially severe mental illnesses, are associated with increased risk for mortality from COVID-19 [206]. Those with Autism Spectrum Disorders and intellectual disabilities were found to be at greater risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and complications from COVID-19 [207]. Compared to those without a mood disorder, those with a mood disorder are at increased risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization (OR = 1.31) and death (OR = 1.51) but not for COVID-19 susceptibility nor severe events [208]. Those with tobacco use disorder, cannabis use disorder, and cocaine use disorder appear to be at higher risk of breakthrough infections after full vaccination; even when matching for lifetime comorbidities and indicates of socioeconomic disadvantage, those with cannabis use disorder remained at higher risk of breakthrough infection [209]. An independent study based upon retrospective chart-review of electronic health records for over 73 million patients found that those diagnosed with a substance use disorder in the past year were at elevated risk for COVID-19, especially among those with opioid use disorder followed by tobacco use disorder [135]. In sum, these factors may interact synergistically to have disproportionately adverse impacts on those with mental health disorders.

Socioeconomic Disadvantage

The association between low socioeconomic status and mental health conditions has been long documented and has persisted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Even with adjusting for pre-pandemic levels, those facing socioeconomic adversity in the U.K. had elevated rates of depression and anxiety compared to those who did not [13]. Importantly, financial difficulties were associated with a trajectory of deteriorating mental health in the largest longitudinal study in the U.K. [100]. Overall, having lower income and/or less than $5000 in savings has been closely linked to increased depressive symptoms during COVID-19 [9]. Low household income was identified as a key driver of elevated depressive symptoms throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic [138]. A longitudinal study found that decreasing levels of household income corresponded directly to increased levels of depression and anxiety throughout several early months of the pandemic [106]. Income disruption independently predicted greater increases in anxiety symptoms among mothers during the pandemic [64]. Children from lower income households were more likely to suffer adverse mental health effects associated with school closures [77]. A nationally representative survey-based study found that 46% of U.S. adults reported moderate or severe psychological distress, and that those with housing insecurity had a higher likelihood of distress [136]. Unemployment is also associated with higher risk of depression and anxiety [16], and living in deprived neighborhoods predicted a consistently poor trajectory of mental health throughout the pandemic [100]. In the USA, living in impoverished neighborhoods was a risk factor for increased rates of overdose-related cardiac arrest events recorded by emergency medical services [79]. As is often the case in public health crises, those who are most negatively affected are those who were already struggling the most.

Racism

The relationships between experiences of racism and adverse mental health effects have been previously documented [139], and the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a rise in racism and racial discrimination against Asian Americans [140]. Sentiment analysis of over 3,300,000 tweets from November 2019 to March 2020 found a substantial increase (from 9.79% to 16.49%, an increase of 68.4%) in negative tweets referencing Asian individuals, while there was little change in the number of negative tweets about other racial/ethnic minority groups [143]. A study of Asian American families found that over 75% of both parents and children had experienced at least one instance of vicarious racism in person or online since the onset of the pandemic and that perceived racism and racial discrimination were associated with poorer mental health [141]. An online survey study found that about 1/3 of participants reported that they had experienced COVID-19-related racial discrimination and that this was positively associated with depressive symptoms [142]. Of note, Asian individuals in the U.K. were more likely experience longitudinal deterioration in mental health during the pandemic [100]. In these ways, a pandemic that is already taxing heavily the mental well-being of all has been associated with further determinants to psychological health for some due to new and exacerbated racism.

Possible Protective Factors Against Psychopathology During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Unfortunately, the evidence available on factors that may protect against or lessen distress and psychiatric conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic is more limited. Largely, these factors appear to be related to knowledge about the pandemic itself, behavioral adaptations aimed at decreasing risk of infection, coping styles, and higher age.

Increased Age

Demographically, some data suggests that higher age may be a protective factor, as older age was associated with lower anxious and depressive symptoms in nationally representative Italian sample [144]. As discussed previously, the mental health profiles of individuals aged 45 and older were more likely to follow a trajectory characterized by consistently good mental health both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic [100]. Overall, however, the extent to which higher age protects against pandemic-related psychopathology remains unknown.

Healthcare Knowledge and Adoption of Precautionary Measures

Recent evidence indicates that having appropriate healthcare knowledge and the adoption of safety behaviors may protect against psychological distress. In China, scores for COVID-19 knowledge, prevention and control measures, and trend projections were higher among high school students without depressive and anxiety symptoms than in students with depressive and anxiety symptoms [46]. In the overall population, receiving quality health information that was specific and up-to-date as well as adoption of appropriate precautionary measures such as wearing a mask and hand-washing were associated with lower levels of anxiety, depression, and stress [104]. A 10-week longitudinal study of rates of depression and anxiety found a negative correlation between levels of informedness and magnitude of depressive symptoms overtime but a positive relationship between social media use and anxiety [106]. Others studies have also found that a lack of understanding of the pandemic and increased use of social technologies (smartphones, social media, and gaming) led to increased psychological distress in adolescents during COVID-19 [30, 31]. Among Canadian mothers, those who work in healthcare had smaller increases in depressive symptoms compared to mothers who did not work in healthcare [64]. In general, these findings are highly consistent with the notion that adequate, timely knowledge about COVID-19 and precautionary measures may help reduce uncertainty and ameliorate distress during the pandemic.

Psychological Traits and Behaviors

Finally, certain psychological traits and behaviors are associated with lower risk of distress and psychiatric symptoms. Not surprisingly, those who spend more time with close friends and family reported lower levels of distress [5]. Those with higher overall defensive functioning were less likely to develop PTSD during the first month of the pandemic-related lockdown [144]. Negative coping styles predicted higher psychological distress in the early stages of the pandemic among a large convenience sample of Chinese individuals [97], as well as increased risk of PTSD symptoms in Chinese young adults [135]. Other studies have found that coping strategies associated with better mental health include positive reframing, acceptance, humor, mediation, work distractions, and COVID-19 preventative education [177, 178]. In contrast, avoidant coping style predicted higher psychiatric symptoms among third-year medical students during the pandemic [143]. A separate report found that both secure and avoidant attachment styles appear to be protective against moderate-to-severe levels of psychological distress [136]. In parallel, there was a negative correlation between attachment anxiety and the quality of romantic relationships among couples during periods of lockdown [137].

While these preliminary findings are promising, much additional research is needed to better understand protective factors in order to adequately inform potential interventions that may be of benefit to those at risk for psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Psychiatric Manifestations of COVID-19 and Its Aftermath

There is an increasing recognition that COVID-19 is often accompanied by neuropsychiatric symptoms. Furthermore, the emerging phenomenon of “Long COVID-19” is frequently marked by subtle psychological and neurocognitive complaints. Orthogonal lines of evidence show substantial levels of psychiatric sequelae among those who survive and even completely recover, likely due to experiencing illness-related trauma. In this section, we review each of these important topics, beginning first with psychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 and Long COVID-19, briefly focusing on potential pathophysiologic mechanisms, and then covering research on the trauma-related sequelae documented among survivors of COVID-19.

Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of COVID-19 and Putative Pathophysiologic Mechanisms

Although the respiratory tract is presently seen as the primary replication site of the virus, SARS-CoV-2 is also able to infect neurons [139]. Postmortem biopsy studies of COVID-19 patients have confirmed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in endothelial cells of blood vessels supporting brain parenchyma [140]. It is therefore unsurprising that COVID-19 patients have reported a multiplicity of neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with their disease. Psychiatric complaints have been noted in almost 60% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients [141]. These findings were corroborated by additional data showing that up to one-third of COVID-19 patients present with acute changes in behavior, personality, cognition, and level of consciousness [142]. Numerous sources have documented an expansive array of psychiatric symptomatology in patients with ongoing COVID-19 that has included agitation [143], mania [144], anxious and depressive symptoms [145], delirium [146], confusion [140], dysexecutive syndrome [147], and psychosis [142].

The pathophysiology driving psychiatric symptoms in COVID-19 remains uncertain; while precise mechanisms have not been established, a growing consensus focuses on the immunological effects of the disease on brain tissue [158]. Some have suggested that direct neural infiltration by the virus could result in the aforementioned symptoms [147], while others posit that these symptoms could be due to overabundant cytokine production [148]. This latter hypothesis is consistent with findings of a positive correlation between the magnitude of inflammatory markers in the blood of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and the severity of depressive symptoms [145]. The inflammatory hypothesis is further corroborated by an ever-growing line of research supporting the potential role of heightened inflammation in the development and progression of psychiatric diseases [149], including psychoses [150], mood disorders [151], and anxiety disorders [152]. The extent to which neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 are driven by non-specific inflammatory processes versus pathways unique to SARS-CoV-2 infection is presently under exploration by several investigative groups.

“Long COVID-19,” Its Neuropsychiatric Symptoms, and Potential Mechanisms

A period of prolonged symptoms following acute COVID-19 disease, often extending many months after clearance of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has been named “Long COVID-19” or “Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection” (PASC) [153, 154]. Although cardiovascular and pulmonary symptoms are the primary complaints of those experiencing PASC, a significant body of work has shown that neuropsychiatric symptoms are extremely common [155]. COVID “long-haulers” have been noted to suffer from headache, anhedonia, fatigue, and impaired memory and concentration [155, 156]. A large cohort study of individuals who had been hospitalized for COVID-19 in Wuhan, China found that fatigue and anxiety were among the most common symptoms reported at one-year follow-up after discharge [108]. One study found that more than half of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 experienced clinically significant cognitive impairment 3–4 months following discharge and that the magnitude of impairment was associated with d-dimer levels during acute illness as well as the degree of residual pulmonary impairment [157]. Although milder COVID-19 infection does not appear to be associated with cognitive impairment, symptoms of anxiety and depression were elevated at follow-up compared to those individuals unaffected by PASC [158].

The pathophysiology of PASC remains unclear, although multiple hypotheses have been proposed in an attempt to account for the high prevalence of psychiatric symptomatology. One hypothesis suggests that the virus itself induces permanent systemic changes, including potential scarring and/or induction of autoimmune reactions, that, in turn, disrupt healthy neural functioning [154]. Others have proposed that persistent viral reservoirs of SARS-CoV-2 cause chronic inflammation that brings about the myriad reported symptoms [159]. At the time of this writing, however, the causes and pathophysiological mechanisms of Long-COVID-19 are speculative, and it remains diagnostically challenging, if not impossible, to completely distinguish psychiatric symptoms of PASC from psychiatric consequences of the stressful and sometimes traumatic experience of COVID-19 itself, discussed next.

Psychiatric Sequelae of COVID-19

Survivors of COVID-19 are at heightened risk of psychiatric sequelae. Several research groups have observed a positive association between mild infection cases and lasting psychiatric conditions, including stress, anxiety, and depression [160, 161]. A follow-up study that took place 1 month after hospital discharge found that 31% of patients reported depression, 28% reported PTSD, 42% reported anxiety, 40% reported insomnia, and 20% reported symptoms of OCD [171]. 23% of patients discharged from a hospital in Wuhan, China, had anxiety or depression at 6 months follow-up [162]; strikingly, the same group found that this increased to 26% at 12 months follow-up [163]. A meta-analysis found that fatigue (58%) and attentional disorder (27%) were among the top-five most commonly experienced symptoms among those who had recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection [169]. Whether these symptoms are due to PASC or secondary psychological consequences of COVID-19, or both, is unclear. Of note, however, is that rates of psychopathology due to COVID-19 are higher than those observed among patients admitted for influenza or other respiratory tract infections [164]. A large retrospective cohort study found that those without psychiatric histories had increased incidences of first psychiatric diagnosis at 14–90 days compared to those who had experienced six other health conditions [165], indicating that not just symptoms but also full psychiatric disorders can occur after the disease.

COVID-19 has also been linked with higher incidence of PTSD due to trauma induced by infection itself, as well as pandemic-associated stress, loss, and restrictive measures. About 13% of Chinese young adults had symptoms of PTSD in the first month of the pandemic [135]. One study found that almost 30% of the Italian population had PTSD symptomatology during the onset of the pandemic [170]. Almost 30% of individuals who had presented for emergency care with COVID-19 met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD 30–120 days later [172], although these rates have varied by the duration of follow-up [173]. Undoubtedly, the pandemic has precipitated vast amounts of psychiatric illness and will likely continue to do so, thus necessitating the need for robust clinical monitoring and treatment interventions.

Psychological and Behavior Adaptation Strategies

We have thus far described the substantial body of work showing adverse psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and those factors that may place individuals at increased risk of such effects. In the section that follows, we utilize empirical data to propose potential strategies for reducing negative psychological and psychiatric consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as adaptive approaches to decrease the likelihood of additional worsening of mental health overall. Importantly, effective psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacologic treatments are still the mainstay of treatment for new psychiatric conditions. At the same time, interventions developed specifically for the COVID-19 pandemic have shown early evidence of efficacy, and the delivery of mental health services through virtual approaches has expanded dramatically to meet individual needs during times of social distancing and quarantine measures.

While several factors inherently contribute to the risk of lasting psychological symptoms due to COVID-19, research during the pandemic has highlighted successful methods of overcoming distress. From a cognitive perspective, mindfulness, optimism, and a sense of trust have been considered protective, as measured by tools such as the Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale and the Life Orientation Test [39, 176]. An impressive clinical trial consisting of over 20,000 participants across 87 countries found that a brief intervention utilizing cognitive reappraisal, an emotion-regulation technique, was effective in both reducing negative emotions and increasing positive emotions [175]. Additionally, interventions to target uncertainty tolerance among children have been specifically suggested [214].

Many groups have called for improvement of remote psychiatric infrastructure in order to provide patients with the social support and mental health services they need during the pandemic [179,180,181]. Importantly, evidence-based guidelines on the appropriate and effective use of telepsychiatry-based mental health services have been developed and continue to evolve as more data emerge [192]. Intriguingly, there may be adherence and attendance advantages to remote versus in-person psychological service appointments for those with dementia [193] and adults receiving CBT for major depressive disorder [187], among others. Several successful remote clinical psychiatry efforts, which included the delivery of CBT, psychopharmaceutical management, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, improved symptoms and functioning for individuals of diverse backgrounds, including frontline healthcare workers and those with an existing psychiatric disorder [118, 182,183,184,185,186]. During the 6 months of lockdown in Wuhan, China, there was increased usage of a publicly available computerized CBT training program that was found to be effective in reducing the severity of both depression and anxiety [174]. Pilot data from a telecare-based model of case-management for home-bound elderly persons in China did not find evidence of benefit for overall self-efficacy and self-care behaviors; however, higher medication adherence and better quality of life were associated with the telecare intervention [210]. A small study found that patients with PTSD preferred face-to-face visits compared with telepsychiatry sessions, but most reported that they would continue treatment via virtual platforms [205].

Additional lifestyle factors and intervention programs aimed at relaxation training are of benefit to those both with and without psychopathology during COVID-19. Exercise was shown to deter psychological symptoms, while reliance on digital entertainment and the news actually increased the risk of depression and anxiety [38, 198,199,200]. Outdoor exercise has also been effective at counteracting perceived reductions in mental health during the pandemic, particularly in the context of increased time with several types of screens [201]. Alternative physical relaxation strategies that provided mental health benefits include yoga and progressive muscle relaxation [202]. Furthermore, progressive muscle relaxation showed benefit in reducing anxiety and improving sleep in a small study of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 [203]. A self-help relaxation and mindfulness training program may also be beneficial to those with COVID-19 and mild-to-moderate anxiety or depression [204]. Brief crisis intervention focused on psychological support led to improved quality of life and reduced stress, depression, and anxiety among those with COVID-19 [205].

The ability of individuals to have support networks, either in-person or digitally, during lockdowns was also highly protective against mental health deterioration [187,188,189]. However, lockdowns with other individuals have also been cited as a source of distress or even physical harm [190, 191]. For this reason, we believe that additional emphasis should be placed on remote couples or family therapy for the ongoing pandemic and future lockdowns, as strong bonds can be therapeutic. Information on interesting activities to do as a group should also be regularly disseminated. Policy suggestions have been developed to further support and address new challenges faced by informal (unpaid) caregivers, such as parents, including assistance in helping families form “closed support bubbles,” consisting of small groups of families providing mutual support, companionship, and assistance to members in need [203]. Others [204] have developed perinatal planning guides in light of the unique burden the pandemic has placed upon perinatal women. These guides are designed to help decrease the chances of and impacts from perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, and they consist of both concrete steps to prevent or alleviate future challenges that could be expected and information on available evidence-based treatments for women during this time [204].

Lockdown orders and school closures have also left children in a mentally vulnerable position, as elevated rates of depression and anxiety have been noted in kids as young as 6 years old [41]. This consideration is important from both the perspective of impaired social interaction skills and inability to access mental health attention, which is often provided in the school setting [194]. During this pandemic there was a dearth of information for guiding parents on child-raising during a lockdown and preventing a trajectory towards psychological distress. Based on cited risk factors, potential strategies include limiting screen time, regularly providing interactive activities and parent-child discussions, promoting digital interaction with other children, and ensuring access to pediatric care [212,213,214]. Without sufficient additional supports to parents, especially those among low-income and disadvantaged groups, gaps in educational achievement and mental health are likely to become further exacerbated by the ongoing pandemic [127].

The well-being of healthcare workers similarly deserves special attention, and a small number of studies have reported on promising interventions aimed at increasing coping skills and treating psychological distress. The Toolkit for Emotional Coping for Healthcare Staff (TECHS) is an online resource to help screen for traumatic stress reactions among healthcare workers that also has demonstrated efficacy in helping them develop coping skills based upon principles of family therapy and cognitive-behavior therapy [215]. Additionally, mindfulness-based stress reduction demonstrated efficacy in improving quality of sleep among nurses working COVID-19 hospital treatment units [216]. Finally, cannabidiol was found to further decrease symptoms of emotional distress and burnout among frontline healthcare workers caring for those COVID-19 when added to standard care [217]. It is our hope that continued research provides a robust foundation for evidence-based treatment approaches for the prevention and treatment of psychological distress and psychiatric conditions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

The adverse psychological and psychiatric impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have been paralleled only by the devastating loss of life and physical illness affecting individuals, families, and communities worldwide. Unprecedented in the resulting chronic social isolation, sweeping unemployment, and constant uncertainty, the pandemic has and will likely continue to negatively impact the mental health of the global population.

While there has been a broad and global increase in distress, psychiatric symptoms, and mental health disorders, investigators have identified heterogeneity in patterns of psychopathology over time and groups of individuals defined by several sociodemographic, occupational, and familial factors. Young people, women, those with pre-existing psychiatric conditions, the poor, and members of racial and ethnic minorities have suffered disproportionately higher degrees of adverse psychological consequences of the pandemic. Increasing substance abuse, drug overdose, and suicidal ideation pose active threats of elevated rates of suicide. Particularly troubling phenomena are already increased rates of suicide among people of color in the USA and suggestive evidence from multiple countries of worsening child abuse and neglect.

With a continually improved understanding of the negative psychological effects of the pandemic and the risk and protective factors for those effects, evidence-based treatment and prevention efforts may be implemented successfully to reduce the overall burden of mental illness; indeed, nascent research reviewed herein is cause for cautious optimism. Ongoing investigative efforts should continue to unveil ways in which individuals and societies can best adapt to a new world in which COVID-19 is an inevitable fact of life.

Further Readings

Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2):e100213.

Li S, Wang Y, Xue J, Zhao N, Zhu T. The impact of covid-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: a study on active weibo users. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2032.

Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231924.

Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112921.

Zhang Y, Ma ZF. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2381.

Choi EPH, Hui BPH, Wan EYF. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during covid-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3740.

Dodds PS, Harris KD, Kloumann IM, Bliss CA, Danforth CM. Temporal patterns of happiness and information in a global social network: Hedonometrics and Twitter. PLoS One. 2011;6:26752.

Viglione G. Has Twitter just had its saddest fortnight ever? Nature. 2020.

Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic key points + invited commentary. JAMA. 2020;3:e2019686.

CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Indicators of anxiety or depression based on reported frequency of symptoms during the last 7 days. Household Pulse Survey. Atlanta: CDC National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. [cited 2021 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm.

CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Early release of selected mental health estimates based on data from the January–June 2019 National Health interview survey. Atlanta: CDC National Center for Health Statistics; 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm.

Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1049–57.

Kwong ASF, Pearson RM, Adams MJ, Northstone K, Tilling K, Smith D, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. Br J Psychiatry. 2021;218:334–43.

Pieh C, Budimir S, Probst T. The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. J Psychosom Res. 2020;136:110186.

di Giuseppe M, Zilcha-Mano S, Prout TA, Perry JC, Orrù G, Conversano C. Psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 among Italians during the first week of lockdown. Front Psych. 2020;11:1.

Solomou I, Constantinidou F. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and compliance with precautionary measures: age and sex matter. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1–19.

Naser AY, Dahmash EZ, Al-Rousan R, Alwafi H, Alrawashdeh HM, Ghoul I, et al. Mental health status of the general population, healthcare professionals, and university students during 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. 2020;10:e01730.

Santomauro DF, Herrera AMM, Shadid J, Zheng P, Ashbaugh C, Pigott DM, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700–12.

Guessoum SB, Lachal J, Radjack R, Carretier E, Minassian S, Benoit L, et al. Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113264.

Racine N, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Korczak DJ, McArthur BA, Madigan S. Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: a rapid review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113307.

Hillis SD, Unwin HJT, Chen Y, Cluver L, Sherr L, Goldman PS, et al. Global minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19-associated orphanhood and deaths of caregivers: a modelling study. Lancet. 2021;398:391–402.

Chen F, Zheng D, Liu J, Gong Y, Guan Z, Lou D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:36–8.

Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142–50.

Lu W. Adolescent depression: national trends, risk factors, and healthcare disparities. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43:181–94.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Otto C, Adedeji A, Devine J, Erhart M, et al. Mental health and quality of life in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic—results of the copsy study. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(48):828–9.

Bruni O, Breda M, Ferri R, Melegari MG. Changes in sleep patterns and disorders in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorders and autism spectrum disorders during the COVID-19 lockdown. Brain Sci. 2021;11(9):1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091139.

Tessarollo V, Scarpellini F, Costantino I, Cartabia M, Canevini MP, Bonati M. Distance learning in children with and without ADHD: a case-control study during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Atten Disord. 2022;26(6):902–14.

Breaux R, Dvorsky MR, Marsh NP, Green CD, Cash AR, Shroff DM, et al. Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: protective role of emotion regulation abilities. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2021;62(9):1132–9.

Xiang M, Zhang Z, Kuwahara K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents’ lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63:531–2.

Tandon PS, Zhou C, Johnson AM, Schoenfelder Gonzalez E, Kroshus E. Association of children’s physical activity and screen time with mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2127892.

Karci CK, Gurbuz AA. Challenges of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nord J Psychiatry. 2021. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ipsc20.

Chen IH, Chen CY, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Lin CY. Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 school suspension. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:1099–1102.e1.

Sharma V, Reina Ortiz M, Sharma N. Risk and protective factors for adolescent and young adult mental health within the context of COVID-19: a perspective from Nepal. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:135–7.

Suffren S, Dubois-Comtois K, Lemelin J-P, St-Laurent D, Milot T. Relations between child and parent fears and changes in family functioning related to COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041786.

Swedo E. Trends in U.S. Emergency Department visits related to suspected or confirmed child abuse and neglect among children and adolescents aged 18 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019–September 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1841–7.

Holland KM, Jones C, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Idaikkadar N, Zwald M, Hoots B, et al. Trends in US Emergency Department visits for mental health, overdose, and violence outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiat. 2021;78(4):372–9.

Saunders N, Plumptre L, Diong C, Gandhi S, Schull M, Guttmann A, et al. Acute care visits for assault and maltreatment before vs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2:e211983.

Loiseau M, Cottenet J, Bechraoui-Quantin S, Gilard-Pioc S, Mikaeloff Y, Jollant F, et al. Physical abuse of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic: alarming increase in the relative frequency of hospitalizations during the lockdown period. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;122:105299.