Abstract

The long term performance of the railway tracks is a relevant topic and a major concern of the railway Infrastructure Managers due to the technical and economical aspects related to the degradation of the track. Thus, there are several factors that have a significant influence on the short and long term performance of the ballasted and ballastless tracks. One of these factors is the train speed (which also includes the critical speed) since the stresses and strains are significantly amplified. This work tries to compare the short but mostly the long term performance of the ballasted and the ballastless track (Rheda system) and also an optimised version of the Rheda system, where the support layers (HBL and FPL) are omitted. This comparison includes the influence of the train speed (and critical speed) and it is based on the stress levels and cumulative permanent deformation induced by the passage of the train. The results were obtained using a hybrid methodology between the 2.5D FEM-PML (to model the short term behaviour) and the implementation of an empirical permanent deformation model (to analyse the long term performance).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The short and long term performance of the railway structures in general and the subgrade, in particular, have an important influence on the track maintenance operations and respective costs [1, 2]. In order to reduce the maintenance procedures and increase the robustness and efficiency of the railway structures, it is important to fully understand the short-term but also the long-term behaviour of the subgrade when submitted to the cyclic loads such as the passage of the train. The short-term behaviour is characterised by the resilient modulus (Mr) and the long-term behaviour is characterised by the permanent deformation (εp). Using these two concepts, the subgrade can be characterised through the laboratory tests such as the cyclic triaxial tests. Where the samples are submitted to cyclic loads [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. However, it is important to have an integrated approach where the whole performance of the subgrade is analysed in the track environment considering the passage of the vehicle.

This work aims to compare the performance of the conventional ballasted track, Rheda system ballastless track, and an optimised ballastless track only constituted by the concrete slab. This optimised ballastless track allows understanding the importance of the support layers in the response of the track. The obtained conclusions can be used as guidelines for possible optimisations. Furthermore, the influence of the train speed in the short but mostly in the long-term performance of the subgrade is analysed in detail. This study also includes the analysis of the influence of the critical speed since the strong amplification of the response can significantly increase the track degradation [14,15,16,17].

The analysis is focused on the subgrade layer. The stresses induced by the passage of the train are obtained using the 2.5D FEM-PML approach. This methodology is articulated with the implementation of an empirical permanent deformation model that uses these stress results and the number of loading cycles as the main inputs to determine and compare the permanent deformation and respective cumulative permanent deformation.

2 Railway Track Modelling: Train-Track-Ground System

Sub-structured models can be used to model the train-track systems and the interaction between both. This approach allows simplifying the modelling since both structures are modelled separately keeping the compatibility between both and respecting the equilibrium restrictions [18].

In this work, the track-ground system is modelled using the 2.5D FEM-PML approach. With this methodology, it is possible to reduce the computational effort and consider the 3D nature of the problem [18,19,20]. The methodology used in this work is described in more detail in the work developed by [18].

Due to the 3D and transient characters of the problem, Perfectly Matched Layers (PML’s) were applied on the boundaries. This special treatment allows avoiding spurious reflections. This methodology was previously implemented with satisfactory results [21]. In this method, an external layer of the interest domain is implemented. This “special” layer absorbs the energy of the waves that impinge the boundaries. This methodology is described in more detail in the work developed by [21].

Thus, the track-ground structure is modelled by the 2.5D-FEM-PML approach and the train is modelled considering a multi-body formulation. The models are coupled numerically following a compliance formulation. The interaction problem implies the compatibility of displacements and load equilibrium at the contact points between the rolling stock and the track. The wheel-rail contact is simulated applying the concept of the linearized Hertzian stiffness (this only considers the dead load transmitted by the wheelset and only the vertical movement of the train is taken into account). More details about this methodology and formulation can be found in [22].

The 2.5D FEM-PML methodology allows obtaining the stress levels induced by the passage of the train that are posteriorly used as inputs to simulate the long-term behaviour of the subgrade of the railway structures.

3 Long Term Behaviour: Subgrade Modelling

The selected empirical permanent deformation model to study the long-term performance of the subgrade is based on the work developed by [23]. This model combines the effect of the elastic stress state in the soil with the number of load cycles. Posteriorly, [24] updated the model, suggesting some modifications as the introduction of influence of the initial stress state:

where pam and qam are the amplitude of the mean stress and deviator stress induced by the train loadings, m and s are defined by the yielding criterion q = s + mp; and pini and qini are the mean and deviator stresses considering the initial stress state.

The model presents several advantages since it considers the amplitude of the applied load, the proximity of the stress path to the failure line and integrates the influence of the initial stress state. Comparing to other empirical models [25, 26], this model is more complex because it depends on more parameters but. at the same time, it is very easy to implement.

The material parameters used in this study were obtained in [11] considering \({\varepsilon }_{1}^{p0}\) = 0.00093, B = 0.2 and a = 0.65. According to the unified soil classification, this material is classified as non-plastic silty sand.

Thus, the model developed by [24] was implemented to study the long-term performance of the railway structures through the determination of the cumulative permanent deformation. The model is applied to the subgrade material (including the FPL—frost protection layer in the case of the ballastless track) and the analysis does not include the ballast. The cumulative permanent deformation (δ) is the sum of the product of the permanent deformation (applying expression 1) of each element of the selected alignment, considering N = 1,000,000 cycles and the thickness of the element:

where i represent the number of elements of the alignment, h is the thickness of the element (in m) and εp is the permanent deformation (dimensionless) and it is obtained through expression 1. The cumulative permanent deformation is maximum at the bottom of the model since corresponds to the sum of the permanent deformation of all elements. However, the elements that most contribute are close to the surface [27].

4 Case Study

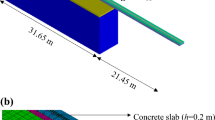

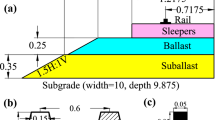

In this analysis, the long-term performance of the subgrade is analysed and compared considering three different railway structures: the ballasted track, ballastless track (Rheda system), and a special optimised ballastless track. The numerical models of each structure are presented in Fig. 1.

(Adapted from [30])

Numerical models: a ballasted track; b ballastless track (Rheda system); c ballastless track with only a concrete slab

The comparison of the performance is carried out under 6 different train speeds: 80, 144, 200, 300, 360 and 500 km/h. The properties of the materials are described in Tables 1 and 2.

Regarding the numerical modelling, the railway structures were modelled by finite elements with 8 nodes. The ballasted track is composed of the rails, railpads, sleepers, ballast, sub-ballast and subgrade. The ballastless track is composed of the rails, railpads, concrete slab, a support layer (hydraulically bound layer—HBL), and also the frost protection layer (FPL). The optimised ballastless track is similar to the Rheda system but, in this case, the support layers (HBL and FPL) were omitted. The rails correspond to the UIC60 model and the railpads were modelled with stiffness and damping of 600 kN/mm and 22.5 kNs/m, and 40 kN/mm and 8 kNs/m in the case of the ballasted track and ballastless track, respectively. The remaining materials were modelled as linear elastic. This assumption is valid since we are dealing with small strains. The sleeper was modelled as a continuous and orthotropic element. This means that, in the longitudinal direction, the stiffness of the ballast is adopted [18].

The initial stresses were obtained considering an isotropic stress state (K0 = 1) and, as depicted in Fig. 1, the modelling takes into account the symmetric conditions of the problem.

In the ballastless track (Rheda system), to simplify the modelling and the analysis of the problem, the FPL was included in the subgrade layer since both materials share the same stiffness. Indeed, they are very similar, and the main difference is related to the density. This simplification able us to compare and discuss the numerical results of the finite elements from the different railway structures at the same depth, which means that they would have an analogous initial stress state [27].

The adopted vehicle is the Alfa Pendular train. This train presents a symmetry plane and is composed of 6 car bodies. Regarding the loading, the average axle load is close to 135 kN. In this case, only the mass of the wheelsets was considered in the model. This assumption is aligned with the studies performed previously by [28, 29] in the scope of the ground vibrations.

4.1 Generation of the irregularity’s Profile

In order to simulate and consider the dynamic mechanism, an unevenness profile was artificially generated. This profile was defined by a sinusoidal function described by a number of harmonics. In this process, the PSD (Power Spectral Density) function defined by the FRA (Federal Railroad Administration) was used. More details about this methodology can be found in [27].

The generated profile is depicted in Fig. 2, it is composed of 120 frequencies and it was defined considering a geometric progression. This profile was determined following the recommendations described in [31].

This study is focused on element 1 (Fig. 1) located at x = 0 m (Fig. 2).

4.2 Short-Term Performance

Firstly, to understand the amplification phenomenon of the stresses (as well as the permanent deformations) for higher speeds, two train speeds closer to the critical speed were evaluated (360 and 500 km/h). The critical speed of each system was determined through the dispersion curves, which is an approximation method but very expeditiously and efficient [32]. Indeed, [14] show that, when the ground is homogeneous, the characteristics of the track can be neglected since the critical speed is almost the same, regardless of the type of structure. In the case of this study, the ballasted track and ballastless track are characterised by a critical speed of 515 km/h and 540 km/h, respectively. The critical speeds were determined based on the results depicted in Fig. 3. More details about this methodology can be found in [32]. Dispersion curves associated with more rigid tracks are curves associated with lower frequencies than tracks with lower rigidity. Thus, it is tempting to think then that the higher the stiffness of the track, the higher the critical speed of the system. But this may not be true, since the ground dispersion curve will also influence the point of intersection, and it is known that the critical speed of the systems is usually conditioned by the characteristics of the ground. The results depicted in Fig. 3 show that, since the ground is homogeneous, to determine the critical speed of the structure, it was only necessary to obtain the slope of the red line because the inverse of the slope is equal to the critical speed.

From experimental results (mostly in the ballasted track) documented in the bibliography ([33] based on the work developed by [34]), it is possible to state that when the train’s speed exceeds 75% of the critical speed, the amplitude of the dynamic response of the track increases rapidly. Indeed, 75% of critical speed can be assumed as the practical speed limit of the ballasted railway tracks. This means that the value of 360 km/h is perfectly acceptable as a practical speed limit [27]. The superior value of the critical speed of the ballastless track can be justified by the stiffness of the track.

Therefore, to assess the influence of the nearing of the critical speed, a higher train’s speed than 360 km/h was considered: 500 km/h. This value is higher than 360 km/h and lower than 515 or 540 km/h. Indeed, it is possible to conclude that this speed is unrealistic, but its results are presented to show the ability of the method to capture the behaviour of the structure when submitted to this range of speeds.

In order to compare the short-term performance, the stress paths were determined for each railway structure (Fig. 4). Considering the previous information about the critical speed, the trains’ speed equal to 500 km/h was only considered for the ballastless track (Rheda system). In the other railway structures, the stress paths go beyond the yielding criterion, which is not a realistic situation since it is expected to have stresses’ distribution. Thus, for the ballasted track, and considering this particular stiffness of the subgrade and FPL (Mr = 120 MPa), the train´s speed of 500 km/h is too much close to the critical speed (515 km/h), which leads to significant amplification of the stresses. This situation does not occur in the ballastless track (where the critical speed of the system is 540 km/h). In the case of the ballastless track only with concrete slab, the results show that the absence of the support layers can influence the stress results when the speeds are closer to the critical speed.

Analysing the obtained results (Fig. 4), it is possible to conclude:

-

The train’s speed is one of the factors that most influence the stress levels and stress paths on the subgrade;

-

For reduced train speeds, the amplification of the dynamic stresses is very small or residual; With the increase of the train’s speed, there is an amplification of the stress levels;

-

Significant amplification of the dynamic stresses when the train’s speed is getting closer to the critical speed of the system (360 and 500 km/h). In fact, for the ballasted and ballastless track (only with a concrete slab), the stress path of element 1 goes beyond the yielding criterion. In the case of the optimised ballastless track, this is due to the amplitude of the stress level and the low value of the initial mean stresses. Indeed, from v = 360 km/h, the amplification of the stress paths is more prominent in the ballasted track, followed by the optimised ballastless track.

4.3 Long-Term Performance

The amplitude of the stress paths as well as the values of the initial stress are important variables and are used as inputs in the empirical permanent deformation model. This means that the stress results presented in Fig. 4 have an impact on the cumulative permanent deformation and, consequently, on the degradation of the railway tracks.

The results of the cumulative permanent deformation are depicted in Fig. 5. Regarding the cumulative permanent deformations, the ballastless track (only with a concrete slab) shows higher values. In Fig. 5f) are depicted the values for the ballastless track (Rheda system) but considering a train’s speed of 500 km/h to understand the magnitude of these displacements. The results were obtained in the alignment of element 1 depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 5 also shows that there is a small difference between the ballasted track and the ballastless track in terms of cumulative permanent deformation. Indeed, this value would be higher if the permanent deformation of the ballast was considered (the influence of the ballast was neglected in this study). Thus, it is important to highlight that this is a comparison at the subgrade level, which justified the similarity of the performance of the subgrade.

The ballastless track with only the concrete slab shows higher cumulative permanent deformation and the difference is significant, which evidences the importance of the support layers (HBL and FPL). This difference is due to reduced initial mean stress, which leads to higher values of cumulative permanent deformation since the stress path is closer to the yielding criterion (Fig. 4).

The results also show that the cumulative permanent deformation is almost constant until v = 200 km/h. From this train speed, there is an increase in the cumulative permanent deformation in each structure due to the amplification of stresses. This amplification is higher when the train speed is closer to critical speed.

5 Conclusions

This work aims to compare the performance of the ballasted and ballastless tracks in terms of stresses and cumulative permanent deformations.

The stress levels are analysed by a numerical tool (2.5D FEM-PML approach), the permanent deformation is evaluated through the implementation of an empirical permanent deformation model and the results are presented in terms of cumulative permanent deformations.

Regarding the ballastless track, two structures are modelled to evaluate the influence of the support layers in the response of the subgrade. This analysis may be helpful in future optimizations of the ballastless track. The obtained results are a product of a simplification in the ballastless track (Rheda system) since for calculation purposes, the FPL was integrated into the subgrade.

The obtained results show that the train’s speed has a significant influence on the response of the subgrade, which also includes the influence of the approaching to the critical speed. When the train’s speed is reduced (i.e., v = 80 km/h until v = 200 km/h), the dynamic responses are not significantly amplified. When the train’s speed increase and it is getting closer to the critical speed (v = 360 km/h to v = 500 km/h), the amplification’s effects growth.

This study shows that the presence of irregularities, the moving character of the loads allied to the train speed can be crucial parameters in the design and future performance of railway structures. Furthermore, both ballasted and ballastless tracks present similar responses regarding long-term behaviour. Moreover, this analysis shows that the ballastless track with only a concrete slab can be an option instead of the “ordinary” ballastless track—Rheda system—(despite the higher absolute values of the permanent deformation because of the low values of the initial mean stresses) since the amplification of the stresses is similar to the remaining structures.

References

Selig, E.T., Waters, J.M.: Track Geotechnology and Substructure Management. Thomas Telford Services Ltd., London (1994)

Nielsen, J.C.O., Li, X.: Railway track geometry degradation due to differential settlement of ballast/subgrade—numerical prediction by an iterative procedure. J. Sound Vib. 412, 441–456 (2018)

Li, D., Selig, E.T.: Cumulative plastic deformation for fine-grained subgrade soils. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 122(12), 1006–1013 (1996)

Puppala, A.J., Mohammad, L.N., Allen, A.: Permanent deformation characterization of subgrade soils from RLT test. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 11(4), 274–282 (1999)

Correia, A.G., Biarez, J.: Stiffness properties of materials to use in pavement and rail track design. In: Geotechnical Engineering for Transportation Infrastructure. Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering. Amsterdam, Netherlands (1999)

Rahim, A.M., George, K.P.: Models to estimate subgrade resilient modulus for pavement design. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 6(2), 89–96 (2005)

Gomes Correia, A.: Innovations in design and construction of granular pavements and railways. In: Advances in Transportation Geotechnics—Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Transportation Geotechnics. CRC Press, Taylors & Francis Group, Nottingham, UK (2008)

Puppala, A.J., Saride, S., Chomtid, S.: Experimental and modeling studies of permanent strains of subgrade soils. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 135(10), 1379–1389 (2009)

Ng, C.W.W., et al.: Resilient modulus of unsaturated subgrade soil: experimental and theoretical investigations. Can. Geotech. J. 50(2), 223–232 (2013)

Gomes Correia, A., Cunha, J.: Analysis of nonlinear soil modelling in the subgrade and rail track responses under HST. Transp. Geotech. 1(4), 147–156 (2014)

Salour, F., Erlingsson, S.: Permanent deformation characteristics of silty sand subgrades from multistage RLT tests. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 18(3), 236–246 (2015)

Ling, X., et al.: Permanent deformation characteristics of coarse grained subgrade soils under train-induced repeated load. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 15 (2017)

Rahman, M.M., Gassman, S.L.: Permanent deformation characteristics of coarse grained subgrade soils using repeated load triaxial tests. In: Meehan, C.L., et al. (eds.) Geo-Congress 2019, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, pp. 599–609

Alves Costa, P., et al.: Critical speed of railway tracks. Detailed and simplified approaches. Transp. Geotech. 2, 30–46 (2015)

Mezher, S.B., et al.: Railway critical velocity—analytical prediction and analysis. Transp. Geotech. 6, 84–96 (2016)

Tang, Y., Xiao, S., Yang, Q.: Numerical study of dynamic stress developed in the high speed rail foundation under train loads. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 123, 36–47 (2019)

Hu, J., et al.: Investigation into the critical speed of ballastless track. Transp. Geotech. 18, 142–148 (2019)

Alves Costa, P., et al.: Influence of soil non-linearity on the dynamic response of high-speed railway tracks. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 30(4), 221–235 (2010)

Yang, Y., Hung, H.: A 2.5D finite/infinite element approach for modelling visco-elastic body subjected to moving loads. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 51(11), 1317–1336 (2001)

Sheng, X., Jones, C.J.C., Thompson, D.J.: Prediction of ground vibration from trains using the wavenumber finite and boundary element methods. J. Sound Vib. 293(3–5), 575–586 (2006)

Lopes, P., et al.: Numerical modeling of vibrations induced by railway traffic in tunnels: from the source to the nearby buildings. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 61–62, 269–285 (2014)

Alves Costa, P., Calçada, R., Silva Cardoso, A.: Track–ground vibrations induced by railway traffic: in-situ measurements and validation of a 2.5D FEM-BEM model. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 32(1), 111–128 (2012)

Gidel, G., et al.: A new approach for investigating the permanent deformation behaviour of unbound granular material using the repeated load triaxial apparatus. Bulletin des Laboratoires des Pont et Chaussées 233, 5–21 (2001)

Chen, R., et al.: Cumulative settlement of track subgrade in high-speed railway under varying water levels. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2(4), 205–220 (2014)

Korkiala-Tanttu, L.: A new material model for permanent deformations in pavements. In: Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Bearing Capacity of Roads and Airfields. Trondheim, Norway (2005)

Rahman, M.S., Erlingsson, S.: A model for predicting permanent deformation of unbound granular materials. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 16(3), 653–673 (2015)

Ramos, A., et al.: Stress and permanent deformation amplification factors in subgrade induced by dynamic mechanisms in track structures. Int. J. Rail Transp. 1–33 (2021)

Alves Costa, P., Calçada, R., Silva Cardoso, A.: Influence of train dynamic modelling strategy on the prediction of track-ground vibrations induced by railway traffic. In: Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 226(4), 434–450 (2012)

Colaço, A., Costa, P.A., Connolly, D.P.: The influence of train properties on railway ground vibrations. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 12(5), 517–534 (2016)

Ramos, A.L., et al.: Influence of permanent deformations of substructure on ballasted and ballastless tracks performance. In: Proceedings of 7th Transport Research Arena TRA 2018, 16–19 Apr 2018. Zenodo, Vienna, Austria

EN13848-5: Railway applications—track—track geometry quality—part 5: geometric quality levels. In EN13848. European Committee for Standardization (CEN), Brussels, Belgium (2008)

Alves Costa, P., et al.: Railway critical speed assessment: a simple experimental-analytical approach. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 134 (2020)

Sayeed, M.A., Shahin, M.A.: Investigation into impact of train speed for behavior of ballasted railway track foundations. In: Advances in Transportation Geotechnics 3. The 3rd International Conference on Transportation Geotechnics (ICTG 2016). Guimarães, Portugal (2016)

Madshus, C., Kaynia, A.M.: High-speed railway lines on soft ground: dynamic behaviour at critical train speed. J. Sound Vib. 231(3), 689–701 (2000)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Ramos, A., Correia, A.G., Calçada, R. (2023). Influence of the Train Speed on the Long Term Performance of the Subgrade of the Ballasted and Ballastless Tracks. In: Dai, H. (eds) Computational and Experimental Simulations in Engineering. ICCES 2022. Mechanisms and Machine Science, vol 119. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-02097-1_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-02097-1_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-02096-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-02097-1

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)