Abstract

The Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve (REBIOSH by its acronym in Spanish) and the Chichinautzin Biological Corridor (COBIO) are mountain zones in the state of Morelos, Mexico, inhabited by peoples conserving a remarkable biocultural heritage. In the REBIOSH, the dominant vegetation is the tropical deciduous forest characterized by its marked seasonality. The region harbors a considerable ethnobotanical richness with 1024 useful species recorded, most of them native, belonging to the families Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Poaceae, and Lamiaceae. Contrastingly, the COBIO is covered by a heterogeneous array of vegetation types, but with 576 useful plant species of the families Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, and Solanaceae. In both mountain areas, nearly 1600 plant species are used, mainly for medicine, ornament, food, and fuel. Despite the differences in dominant vegetation types, both regions are similar regarding the forms of management of some species, which reveals a shared cultural heritage. The ethnobotanical knowledge in both natural protected areas is endangered by migration, land use change, and changes in the cultural patterns, which have a negative impact on the forms of use and management of plant resources. Because these regions represent havens of traditional knowledge and peoples’ cultural heritage, it is essential to systematize and analyze the pattern of plant use to establish priorities for the conservation of biocultural heritage. This chapter is a contribution in this direction.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The state of Morelos – located in central Mexico – covers only 0.3% of the total country’s surface, but its human population occupies the fifth place among the 32 states of the country. Because of its proximity to Mexico City and its touristic infrastructure including hundreds of recreation areas and aquatic parks, the state is one of the preferred destinations for thousands of visitors from the capital city. While Morelos has recently acquired a touristic vocation, its territory has staged human-nature interactions since at least 8000 years ago, when human populations dwelled in the southern part of the state (Juárez-Mondragón 2019), and the first permanent settlements date to 4000 years ago (Corona 2018). Archaeological sites in Chalcatzingo (3500 B.P.; Grove 1984), Xochicalco (1400 B.P.; Garza and Palavicini 2002), the Tepozteco (800 B.P.; INAH 2022), and Teopanzolco (700 B.P.) witness the presence in the state of the Olmec, Olmec-Xicalanca, Tlahuica, and Mexica Mesoamerican cultures (INAH 2022).

During the sixteenth century, the territory of the present state of Morelos was used by the Spaniards as an experimental zone for the acclimatation of exotic crops to sustain the economy of the colony. Between 1527 and 1530, the first plantation of sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum L.) in Mexico was established near Cuauhnáhuac, the current capital city of Cuernavaca (Crespo 2018), together with the planting of mulberry trees (Morus alba L.) for rearing silkworms (Bombyx mori Linnaeus 1758; García 2018). The transformation of the landscape during the colonial period was so drastic that, by 1550, cotton – a crop of Mesoamerican origin – was replaced by mulberry trees (Maldonado 2018).

The ethnobotanical importance of the present state of Morelos during the early colonial period is underscored by the exploration and research made by Francisco Hernández – court physician of Philip II, whose results were published in the Historia Natural de la Nueva España, becoming an essential ethnographic source for documenting the history of disease and medicinal plants in colonial Mexico. The work of Francisco Hernández not only listed the uses of plants of the New Spain, but it was one of the first records in the American Continent of what we now know as medical ethnobotany (Zolla 2018). Hernández documented the use in treatments, forms of preparation, collection sites, vegetation types, and cultural contexts of over 519 medicinal plant species distributed in the present state of Morelos (Parodi 1991).

During the colonial period, several explorers and naturalists studied the natural resources of Mexico, perhaps the most noticeable being Alexander Von Humboldt, who arrived in the country in 1803. Humboldt briefly visited the state of Morelos on his way from Acapulco to Mexico City. Perhaps the most relevant observations made during Humboldt’s transient visit to the state are embodied in his description of the contrasting climates of Morelos from the warm southern to the temperate northern portions, and his estimation of the elevation above the sea level of Cuernavaca – then known as Cuahnáhuac. Humboldt was one of the first to warn about the negative consequences of the introduction of exotic crops and livestock on soils and vegetation.

The introduction of rice (Oryza sativa L.) during the first half of the nineteenth century, particularly in southern Morelos, had strong repercussions on the use of vegetation (SADER 2021), many of which persist until the present. Rice cultivation exacerbated the transformation of the landscape, above all in the tropical deciduous forest covering nearly 70% of the state’s territory. One of the largest consequences of rice cultivation was the way in which water was managed, because rice demands large quantities of irrigation and Morelos is relatively scarce in water due to one of the highest evapotranspiration rates in the country (Maderey 2002).

In the twentieth century, the Mexican Revolution left a deep imprint in the way in which the vegetation was managed in Morelos due to the creation of the Ejido, a regime of social land tenure. The Ejido was a revolutionary conquest because during the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, private tenants accumulated land at a scandalous level. Except for a few zones, most of the state of Morelos’s territory was divided among hundreds of Ejidos having their own authorities and regulations. It was in Morelos where Emiliano Zapata was born, one of the most prominent leaders of the Mexican Revolution, he developed a political ideology summarized in the renowned expression la tierra es de quien la trabaja –translated as “the land belongs to those who work it with their own hands” – adopted by thousands of rural communities throughout Mexico, even nowadays. These historical events are closely related with the present forms of vegetation management.

Currently, most of the state’s surface is covered by forests (58%) in different conservation status, followed by agriculture and livestock (34%), and human settlements (10%) (Escandón-Calderón et al. 2018). The zones covered by natural vegetation in relatively good conservation status are concentrated to the south and north of the state where the main two protected natural areas are located. These are, respectively, the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve (REBIOSH by its acronym in Spanish) and the Chichinautzin Biological Corridor (COBIO).

In both of these protected areas, a diversity of traditional communities use and manage a large number of plant resources and maintain a rich biocultural heritage about the management of natural ecosystems and landscape components. Because of that, the compilation of this knowledge might become an essential contribution to the sustainable management of natural areas in the region. In this chapter, we provide a general account of the use and management of plants in these mountain zones of the state of Morelos, which are in many ways contrasting. We in addition discuss some viewpoints regarding the topics needed to be addressed by future ethnobotanical research in both regions.

Sources of Information for the Study of the Ethnobotany of the Mountain Zones of Morelos, Mexico

For the present research, we made use of 42 sources of information, including scientific papers, dissertations, books, historical archives, technical reports, and databases (22 for the REBIOSH, 16 for the COBIO, and 4 for the whole state of Morelos). Three of these sources were the most important since they summarize regional views. For the REBIOSH, the study by Maldonado (1997), while for the COBIO, the book by Monroy-Ortiz and Castillo-España’s (2007), and also outstanding was the database Etnoflora de Morelos, which represents over 5-year effort of our research team in the Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Conservación (CIByC – UAEM). The database summarizes and documents the use and management of plant resources in the state of Morelos.

Ethnobotany of the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve

Ecological Context

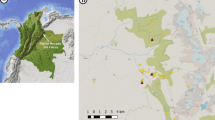

The REBIOSH is a natural protected area in southern Morelos that was decreed in 1999 because of its importance in the conservation of the tropical deciduous forest. It represents a reservoir of species endemic to Mexico due to its mountainous topography with elevations from 700 to 2400 m a.s.l., which favors the formation of microhabitats (Fig. 1). It has a surface of 59,000 ha and its climate is warm subhumid with annual mean temperature of 22.5 °C and average yearly precipitation of 906 mm, mostly falling between June and September. The dry season occurs from October to May, with a driest and warmest period from March to May (Maldonado 1997; CONANP 2005; Bolongaro and Torres 2020). The water bodies in the region are mainly seasonal ephemeral streams.

The most extended vegetation is tropical deciduous forest characterized by trees 5 to 10 m in height dominated by Amphipterygium adstringens (Schltdl.) Standl., Bursera aptera Ramírez, Bursera longipes (Rose) Standl., Bursera morelensis Ramírez, Conzattia multiflora (B.L. Rob.) Standl., Ceiba aesculifolia subsp. parvifolia (Rose) P.E. Gibbs & Semir, Ipomoea murucoides Roem. & Schult., Lysiloma acapulcense (Kunth) Benth., and Lysiloma divaricatum (Jacq.) J.F. Macbr. In the more humid zones like canyons and ravines, the most representative species are Astianthus viminalis (Kunth) Baill., Bursera grandifolia (Schltdl.) Engl., Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb., Euphorbia tanquahuete Sessé & Moc., Ficus petiolaris Kunth, Guazuma ulmifolia Lam., Salix humboldtiana Willd., and Sapindus saponaria L. In zones disturbed by human activities, Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd., Acacia cochliacantha Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd., Pithecellobium acatlense Benth., and Mimosa polyantha Benth. are dominant species (Maldonado 1997; Fig. 2).

Main vegetation types in the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve. (a) and (b) Aspect of the Tropical Deciduous Forest in the rainy season; (c) and (d) contrast between the rainy and dry seasons in the REBIOSH; (e) Cerro Frío is the highest mountain in the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve with 2204 m.a-s.l.; and (f) Oak Forest and an ecotone between Oak Forest and Tropical Deciduous Forest are the predominant types of vegetation in Cerro Frío. José Blancas, with the exception of (b) Darely Acosta

Sociocultural Context of the Peoples in the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve

The history of human settlements in the REBIOSH is comparatively more recent than in other regions of Morelos. Although human occupation in the zone dates back 3000 years, permanent settlements are 1000 years younger, as seen in the archaeological sites in the current localities of Chimalacatlán and Nexpa. At present, the southern region has lower population densities than the northern and central portions of the state (CONANP 2005).

The permanence of the settlements in the REBIOSH that subsisted after the Spanish invasion, and those founded later, was linked to four main events: (i) the exploitation of gold and silver mines; (ii) the introduction of livestock; (iii) the cultivation of sugarcane; and (iv) the creation of Ejidos. Most of the current settlements in the REBIOSH were established in the 1930s, mainly because of the agrarian distribution. In many cases, the creation of Ejidos stimulated the immigration from other parts of the state or from neighboring states like Guerrero, Puebla, and the State of México. This fact caused that the demographic composition of these settlements is heterogeneous. Although most people consider themselves as mestizos, the Nahuatl cultural inheritance is prominent regarding the forms of vegetation management, gastronomy, and traditional botanical nomenclature. Within the REBIOSH, there are 31 rural communities with a population of 23,920 inhabitants organized into 27 Ejidos (CONANP 2005; INEGI 2021). All these rural communities are classified as high marginalized because not all their inhabitants have access to public services like health care, education, sewage, drinking water, and roads.

The main economic activities of people within the REBIOSH are rainfed agriculture of basic crops like maize (Zea mays L.), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.), and squash (Cucurbita pepo L.), and cultivation of commercial crops like sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench), sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.), hibiscus tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.), sesame (Sesamum indicum L.), and pitaya (Stenocereus stellatus (Pfeiff.) Riccob.). People obtain supplementary income from gathering and selling firewood, medicinal plants, and other non-timber forest products like copal resin (Bursera spp.; Maldonado 1997; Trujillo and López-Medellín 2018; Fig. 3).

Main economic activities of the inhabitants of the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve. (a) Seasonal agriculture; (b) cattle raising; (c) propagation of fruit trees in homegardens; (d) firewood collection; (e) cultivation of commercial crops such as pitaya (Stenocereus stellatus); collection of non-timber forest products such as (f) cuachalalate bark (Amphipterygium adstringens); and (g) bonete fruit harvest (Jacaratia mexicana). José Blancas, with the exception of (a) Darely Acosta

Patterns of Use and Management of the Flora of the REBIOSH

Useful Flora

The useful flora of the REBIOSH includes 1024 species in 153 families and 585 genera. The families with most ethnobotanical importance are Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Poaceae, Lamiaceae, Malvaceae, Solanaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Apocynaceae, Cactaceae, Boraginaceae, Rubiaceae, Asparagaceae, Crassulaceae, Moraceae, and Araceae. These 15 families concentrate 51.75% of the useful flora, the remaining 48.24% species are distributed among 138 families (Table 1). These numbers agree with Maldonado’s (1997, 2013) finding of the useful plants within the REBIOSH and the Upper Balsas Basin.

The genera with more useful species are Bursera, Euphorbia, Ficus, Acacia, Ipomoea, Sedum, Senna, and Solanum (Table 2), which might be due to their ecological importance, ease for propagation, and high number of uses of their species. For example, 12 species of Bursera have natural distributions in the REBIOSH and all have at least one use, mostly as living fence, construction, medicinal, and ritual purposes. Also, 11 species of the genus Acacia are native to the REBIOSH and have medicinal, fodder, and fuel uses. In contrast, genera like Cochlospermum have only one useful species, perhaps because it is basically used as ornament.

Provenance of Useful Species

Most useful flora of the REBIOSH, 740 (72.27%) species are native and 281 (27.44%) are exotic, the remaining species having an uncertain origin. According to CONANP (2005), the total and useful flora in the region includes 936 and 602 species, respectively; however, this accounting only considered the native plant species, that is, those naturally distributed in Mexico. In the present research, we recorded 1024 useful species including the native and exotic floras. We estimated that 740 of these useful species are native to Mexico and 520 species are native to the REBIOSH. Our results show an increase (123%) in the useful flora of the REBIOSH, mainly due to the considerable increment in ethnobotanical studies conducted in the region during the last 17 years.

The exotic useful flora plays an important role in meeting the needs of the local people. It may displace the native flora (Ramírez et al. 2020), but provides valuable resources, mainly for ornamental use. Our record of 281 exotic species in the REBIOSH reveals a potential high gene flow promoted by people for different purposes, which should call the attention of conservation regulation policies.

Growth Habit

Regarding the growth habit, the useful plant species include 541 herbs (52.83%), 273 trees (26.66%), 161 shrubs (15.72%), 29 climbing plants (2.83%), 14 palms and rosettes (1.37%), and 6 epiphytes (0.59%). This pattern of growth habit proportions of useful plants may be determined by several factors, one of them depending on the growth habits abounding in the vegetation types (Caballero et al. 1998). The high number of useful herbaceous species might be a consequence of the long history of human-plant interaction in the tropical deciduous forest the long history of management of which favors the development of herbaceous species (Maldonado 1997; Caballero et al. 1998; Maldonado et al. 2013).

Plant Use Categories

We recorded 15 use categories in the REBIOSH, among which medicinal use is the most frequent (72.66%) with 744 plant species, followed by 128 ornamental species (12.5%), 120 species of edible plants (11.72%), and 78 species used as fuel (7.62%; Table 3). The use categories we recorded generally agree with previous reports of ethnobotanical studies made in Mexico and elsewhere in the world (Caballero et al. 1998). The predominance of medicinal use in the REBIOSH is related with the tropical deciduous forest being the vegetation type that provides the largest number of medicinal plants in Mexico (Beltrán-Rodríguez et al. 2017).

We observed a growing number of plant species used as ornamental, a trend that has been occurring during the past two decades even above the increase of edible plant species, which might be due to the modification of plant-use patterns associated to processes of cultural change (Arjona-García et al. 2021).

As stated by Villalpando-Toledo (2020), local culture changes have modified the composition and structure of agroecosystems, a transformation that is evident in homegardens. These were formerly conceived as production units aiming at supplementing the needs of households, but nowadays homegardens are mainly used for cultivating ornamental plants. Alternatively, the predominance of ornamental plants might be due to the present higher number of studies addressing this use category, which could influence a false perception of an increased frequency in their cultivation.

Ecological Status

A total of 474 (46.29%) useful plant species are wild, 294 are cultivated-domesticated (28.71%), 284 are ruderal (27.73%), and 45 are weeds (4.39%). The cross-examination of ecological status and use category shows that 70% of the medicinal plants and 79.45% of the fuel plants are wild, 60.24% of the ornamental plants and 46.62% of the edible plants are domesticated, and 51.28% of the fodder plants are weeds or ruderal plants.

Our results suggest that the suitability of using particular environments – both natural vegetation and anthropogenic areas – depends on the plant resources occurring in these environments (Toledo et al. 2008). Thus, it is common that people use forests for gathering firewood, construction materials, or medicinal plants, while anthropized spaces are preferred over forests to obtain edible plants that normally do not prosper in forests. There are evident exceptions to that, but, more frequently, edible plants from forests are seen as supplementary or emergency foodstuffs (Blancas et al. 2013). The latter considerations are strongly rooted in peoples with a strong agricultural tradition, as is the case of most Mesoamerican cultures.

Management Categories

We recorded four plant management categories in the REBIOSH that are not exclusive because a plant species can be managed in more than one way. Local people gather 718 (70.12%) plant species in the surrounding forest and anthropized areas, 293 (28.61%) plant species are either incipiently or intensely cultivated by several methods (through seed or vegetative propagation), 20 (1.4%) plant species are tolerated, and 3 (0.2%) plant species are protected.

There is a noticeable lack of information about plant management in the REBIOSH and the ethnobotanical studies made in the region include few mentions about it. For many years ethnobotanical studies were limited to listing useful plants, it was until the late twentieth century when topics and methods applied by ethnobotanists became more diverse (Phillips and Gentry 1993). However, plant management in the REBIOSH is far from having been documented, and even plant gathering follows appropriation strategies beyond cropping from nature, involving complex decisions based on socioeconomic factors (González-Insuasti et al. 2008).

The management of copal (Bursera spp.) provides an example of the lack of clarity in the documentation of plant management. The sources of information predating the works of Mena (2018) and Abad-Fitz et al. (2020) classified the extraction of copal products as simple gathering, but these studies documented that current interactions range from gathering from wild populations to harvesting resin from trees cultivated in agroforestry systems. Cultivation of these trees may be by means of cuttings, and more recently, from seeds. For many details, see the chapter Bursera spp. in this book.

Use of Medicinal Plants in the REBIOSH: Current Issues and Strategies for Their Sustainable Management

As mentioned above, we have recorded 744 plant species with medicinal use in the REBIOSH, 581 of them are native to Mexico and 295 have natural distributions in the reserve. We also mentioned that medicinal use is predominant in the REBIOSH and argued that this preponderance is related to the richness of medicinal plants present in the tropical deciduous forests (Beltrán-Rodríguez et al. 2017). The abundance of medicinal plants in tropical deciduous forests may be due to the presence in them of structures that accumulate the secondary metabolites on which medicinal uses are based (Soto-Nuñez and Sousa 1995). In that regard, Albuquerque (2010) hypothesized that seasonal forests are preferred by people as sources of gathered medicinal plants.

Another important factor is the medicinal plant gathering, storage, and commercialization tradition rooted in the Balsas River Basin, of which the REBIOSH is part. As noticed by Hersch-Martínez (2010), since pre-Hispanic times, this region has been a source of exchange and tribute of medicinal plant species, mainly in the form of barks and resins. Nowadays, important centers of accumulation and sale of medicinal plants exist near the REBIOSH, such as the market in Axochiapan and the fair in Tepalcingo, Morelos (Hersch-Martínez 2010; Argueta 2016; Blancas et al. 2020; Fig. 4).

Aspect of the Tepalcingo Tianguis, the most important market in the region of the REBIOSH for the commercialization and exchange of plants and their derivatives. (a) Basketry products; (b) copal resin (Bursera spp.); (c) handicrafts made with bules (Lagenaria siceraria); (d) sale of a great diversity of medicinal plants; and (e) sale of edible plants such as Timbiriche (Bromelia spp.). (Photos: José Blancas)

From these markets, wholesale traders send large quantities of plant materials to regional traditional markets (tianguis) and urban markets, such as the Sonora market in Mexico City. The latter market is ranked as the largest market of medicinal plants in Mexico because of the diversity and volume of medicinal plants traded in it (Linares and Bye 2010). The overharvesting of wild plants to meet urban market demands is one of the factors that endangers some species that are gathered from the REBIOSH.

One of the most illustrative examples of overharvesting is the cuachalalate (Amphipterygium adstringens (Schltdl.) Standl.), a tree from which bark is gathered to treat gastric ulcers and to heal wounds (Beltrán-Rodríguez et al. 2021a). Cuachalalate bark has been used by rural communities since long time ago, but due to the surge of herbalism during the past 20 years, its use has expanded to the point of causing its local extinction due to inappropriate management of its wild populations (Solares et al. 2012). Solares et al. (1992) documented how the overdemand of cuachalalate bark prompts ways of harvesting that endanger the trees by extraction of large portions of bark from individuals, frequently cutting through the vascular cambium, and, in some populations, the trees are felled and debarked. Although the environmental regulation currently in force prohibits the latter destructive practice, it continues to be illegally practiced by inexperienced gatherers.

Regional initiatives have been generated to address this issue. This is the case of the Cuachalalate Productive Chain, which groups 17 communities of the REBIOSH that has established links with social actors, including the scientific community, to create alliances to design sustainable management of this plant species (Solares et al. 2012). Much work needs to be made in that regard since the cuachalalate is a dioic species with a low proportion of female trees, low seed viability and germination rates, and a low seedling establishment rate. Overcoming these drawbacks obligates researchers to make ecological, genetic, and reproductive biology studies to provide tools for its sustainable use (Beltrán-Rodríguez 2018).

The inadequate environmental regulations addressing the vulnerability of medicinal plants in Mexico is another issue that increases pressure over some species populations. The regulation of medicinal plant extraction has contradictions that make highly vulnerable species that are not priority for conservation programs. It assumes that these plants have an extensive distribution thus preventing species from being endangered. However, vulnerability of both wide or restricted distribution species is severely affected by overharvesting and high market demand (Delgado-Lemus et al. 2014).

For instance, the quina amarilla or copalchi (Hintonia latiflora Sessé & Moc. ex DC.) is widely distributed in Mexico, but has low population densities, lacks vegetative propagation structures and its sexual propagation is difficult. Bark of this species is overharvested for its hypoglycemic effects (Cristians et al. 2009); but despite its vulnerability, it is not included in the list of endangered species neither actions are carried out for ensuring its reproduction in wild populations, therefore, the species is highly vulnerable (Beltrán-Rodríguez et al. 2021b).

The opposite situation is illustrated by the palo dulce (Eysenhardtia polystachya (Ortega) Sarg.), whose bark is extracted to treat urinary conditions (Beltrán-Rodríguez et al. 2017) and is included in the IUCN Red List (IUCN 2022); however, its populations seem to remain stable and its current appropriation rates do not represent a major risk. Hence, many plants in the REBIOSH require ecological, ethnobotanical, and general natural history studies to assess their vulnerability and degree of risk from local and regional harvesting.

Another source of vulnerability of medicinal plants extraction is the loss of knowledge regarding its management (Blancas et al. 2020). The 32 communities within the REBIOSH experienced a true exodus of youngsters who emigrate to other areas in Mexico or to the USA (Arjona-García et al. 2021). The result of this emigration is that only elders remain in the communities who, due to the lack of laborers, frequently rent their forest land to regional medicinal plant hoarders, most of which look for immediate profit beyond the conservation of the resources (Blancas et al. 2020). Furthermore, many of these hoarders lack the knowledge and technical skills to ensure the reproduction of many plant species, therefore making the populations of medicinal plants to become vulnerable (Beltrán-Rodríguez et al. 2017).

The loss of knowledge about medicinal plants is associated with changes in the cultural patterns of the local population. The media and some public policies have a high influence on the contempt and misvaluing of traditional medicine, which has contributed to the abandonment of management practices that allowed harvesting medicinal plants without causing harm to its local populations (Arjona-García et al. 2021).

We consider that joint efforts involving different social sectors are required to address these issues and find solutions based on the complementarity of local and scientific knowledge.

One of the efforts that is worth mentioning is the Program of Social Actors of the Medicinal Flora of Mexico, which has been working in the region for over 25 years. This program looks for dialoguing about medicinal plant use and conservation from a transdisciplinary perspective, and to foster and articulate researchers of medical anthropology and ethnobotany. In practice, this program has made outstanding efforts to harmonize domestic and commercial use of medicinal plants, consider the cultural context of traditional medicine, enhance training of health promoters and traditional therapists, value the role of gatherers in the system of wild medicinal flora supply, and promote the exchange of knowledge between traditional physicians, and researchers of the public health systems (Hersch-Martínez 2003).

The Traditional Management of Copal: A Case of Sustainable Appropriation of the Tropical Deciduous Forests in the REBIOSH

The southeastern portion of Morelos is an extraction and trading zone of copal, which together with the neighboring zones in the states of Puebla and Guerrero, provide nearly one-third of the total copal resin commercialized in Mexico (Linares and Bye 2008). Copal resin is a non-timber forest product, which in the REBIOSH is extracted from two species of the family Burseraceae. The main uses of copal are as a ritual resin that is burned to produce fragrant smoke in magic-religious ceremonies and agricultural rituals, and for medicinal purposes to treat some muscular ailments. Perhaps its use began in prehistory, but became highly important during pre-Hispanic time, when several regions of the present Mexico paid it as tribute and traded it with the political power centers (Abad-Fitz et al. 2020).

The Tepalcingo traditional market, located near the limits of the REBIOSH, is one of the most important trading centers of copal that opens just before the Day of the Dead, one of the most important traditional celebrations in Mexico (Cruz et al. 2006; Argueta 2016). A large percentage of the copal resin commercialized in the Tepalcingo market comes from communities within the REBIOSH that are specialized in the extraction of the resin of the copal chino (Bursera bipinnata (DC.) Engl.) and copal ancho (Bursera copallifera (DC.) Bullock). The former species is the most appreciated because of its white resin and intense fragrance (Mena 2018; Abad-Fitz et al. 2020).

In the REBIOSH, the gathering season of copal resin begins in August and ends in late October, just before the Day of the Dead. The management of copal trees involves careful selection focused on the trees’ productivity of resin. The copal resin gatherers, called copaleros, choose the trees based on their vigor and height (Abad-Fitz et al. 2020). Afterwards, incisions are made on the trees from which the resin flows to be collected in leaves of maguey criollo (Agave angustifolia Haw.). Once the selected trees stop producing resin, they are not harvested any further, and may be eliminated (Mena 2018; Abad-Fitz et al. 2020). By that process, highly productive trees are favored in the gathering zones within wild vegetation; an example of in situ management of copal trees.

Copal trees are also propagated in agroecosystems like milpas – a polyculture system with maize, bean, squash, and chili pepper – and grazelands, where the trees are tolerated, promoted, protected, and even vegetatively propagated. More recently copal are propagated through seed sowing (Mena 2018; Abad-Fitz et al. 2020).

As mentioned above, the patterns of use and management of the flora in the REBIOSH have received little attention from researchers, who have considered the copal chino as a wild plant, but the copaleros are developing multiple management strategies. Abad-Fitz et al. (2020) observed copal tree selection patterns in the REBIOSH, finding significant differences in the production and chemical composition of resin between wild and managed trees. In agroecosystems, trees with high production of intensely fragrant resin are more abundant than in unmanaged vegetation, in which most trees produce less resin with less intense fragrance. These results confirm that the copal chino can be considered as a tree under incipient domestication process. Another consequence of the observations of Abad-Fitz et al. (2020) is that, despite the copal chino is a tree with low abundance in the tropical deciduous forests of the Balsas River Basin (Maldonado 2013), the density of the trees is five times higher in sites managed by the copaleros of the REBIOSH, compared with the wild populations of the area.

Therefore, the copal chino can be a key species for the recovery of vegetation, at the same time it provides supplementary economic resources to the local households in a high marginality region. The organization of the copaleros has allowed the copal-producing communities to increase the price per kilogram of the copal resin, improve the commercial networks, and have access to income for improving their productive land and establishing communitarian nurseries (Mena 2018). That also implies that the local communities are acquiring a high level of participation in the development of environmental policies and shows that the management of copal is a sustainable activity with social and cultural value that ensures both the conservation of the natural environment and the livelihoods of local people.

Copal management is an example that can be replicated at REBIOSH with other non-timber forest products. However, its benefits must be recognized in public policies at the regional level. Hence, the copaleros should have an incentive, be it social or even monetary recognition for managing two species of copal that are key to the conservation of the Tropical Deciduous Forest.

Ethnobotany of the Chichinautzin Biological Corridor

Ecological Context

The COBIO is a 37,301 ha natural protected area located in the northern portion of the state of Morelos (Fig. 1) decreed in 1988 with the purpose of safeguarding the region’s wild flora and fauna (Diario Oficial de la Federación 1988). It forms part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, a mountain area that crosses Mexico from east to west, which in the state of Morelos has elevations ranging from 1250 to 3450 m (Santillán-Alarcón et al. 2010). It encompasses three climates: (i) semi-cold (mean annual temperature from 8 to 12 °C and average yearly precipitation between 1200 to 2000 mm), (ii) temperate (16–20 °C and 1000–1200 mm), and (iii) semi-warm subhumid (18–22 °C and 800–1000 mm; García 1988). The COBIO is an aquifer recharge zone receiving high annual precipitation, where bodies of water include a complex network of streams, rivers, and at least seven lakes (Santillán-Alarcón et al. 2010).

The vegetation in the zone includes: (i) Pine Forest dominated by Pinus montezumae Lamb., Pinus hartwegii Lindl., Cupressus lindleyi Klotzsch ex Endl., Alnus jorullensis Kunth, and Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. & Cham.; (ii) Pine-oak Forest with Pinus leiophylla (Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham.), P. montezumae, Pinus pringlei Shaw, Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl., Pinus teocote Schltdl. & Cham., Quercus castanea Née, Quercus crassifolia Bonpl., and Quercus laurina Bonpl., (iii) Oak Forests dominated by Quercus candicans Née, Q. castanea, Q. crassifolia, Q. laurina, Quercus obtusata Bonpl., and Quercus rugosa Née; and (iv) mountain cloud forest with Carpinus caroliniana Walter, Celastrus pringlei Rose, Clethra mexicana DC., Cornus disciflora DC., Meliosma dentata (Liebm.) Urb., Oreopanax peltatus Linden ex Regel, Styrax ramirezii Greenm., Symplocos citrea Lex. ex La Llave & Lex., and Ternstroemia pringlei (Rose) Standl. (Bonilla-Barbosa and Villaseñor 2003; Fig. 5).

The known flora in the COBIO includes 1265 vascular plant species within 153 families and 516 genera. The families with most species are Orchidaceae, Poaceae, Asteraceae, Lamiaceae, and Fabaceae, while the more represented genera are Salvia, Malaxis, Cyperus, Cuphea, Cheilanthes, and Tillandsia. Nearly 20 species in the region are within an endangered species category and six are endemic to the COBIO (Flores-Castorena and Martínez-Alvarado 2010).

Rural Settlements

The COBIO is distributed among 15 municipalities of the states of Morelos, México, and Mexico City, where an estimated number of 34 rural communities have a population of 31,653 inhabitants, 1354 (4.27%) of which consider themselves as indigenous, most of them speakers of Nahuatl (SIMEC 2022). The region has a poverty level from slight to moderate (CONEVAL 2020).

Some of these settlements have existed since pre-Hispanic time, such as Huitzilac, Tepoztlán, Amatlán, Tlayacapan, and Tlalnepantla. The long history of population in the region, relative to human occupation in the southern portion of the state of Morelos, has had consequences in the infrastructure as in the availability of public services. For several centuries, the region has been an access zone for the neighboring Mexico City, and, through it, the commodities brought from Asia and disembarked in the port of Acapulco made their way to the city. One of the main railroads in 1897 connected Mexico City with Cuernavaca, Yautepec, and Cuautla in the state of Morelos, connecting settlements now included in the COBIO (Semo 2020).

The main economic activities in the region are trading, lumbering and extraction of forest topsoil, subsistence and commercial agriculture, and sheep husbandry. The crops grown in the region are those adapted to temperate zones and crops with tolerance to several climates like maize (Zea mays L.) and bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Native and exotic crops produced in the region include oat (Avena sativa L.), peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.), cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.), green tomato (Physalis philadelphica Lam.), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), squash (Cucurbita spp.), chilacayote (Cucurbita ficifolia Bouché), potato (Solanum tuberosum L.), and fruit trees like avocado (Persea americana Mill.), peach (Prunus persica (L.) Batsch), apple (Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh.), prune (Prunus domestica L.), black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.), fig (Ficus carica L.), pear (Pyrus communis L.), and Mexican hawthorn (Crataegus mexicana DC.) (INECC 2022).

Ethnobotany of the COBIO

We recorded a total of 576 useful plant species grouped in 115 families and 378 genera. The families with most used plant species in the COBIO are Asteraceae (76 species), Fabaceae (42), Lamiaceae (29), Solanaceae (28), Rosaceae (18), Malvaceae (17), Amaranthaceae (15), Fagaceae (12), and Orchidaceae, Pinaceae, Rubiaceae, Rutaceae, and Verbenaceae with 11 species each (Table 4). The latter 13 families concentrated 50.7% of the useful species, the remaining 49.3% being distributed in 102 families.

The more represented genera were Quercus (12 species), Pinus (10), Solanum (9), Citrus (8), Salvia (7), Tagetes (6), and Bursera, Chenopodium, Ipomoea, Oenothera, Passiflora, and Tournefortia with five species each (Table 5).

The useful flora in the COBIO represented 30.7% of the total species we recorded in the region, which agrees with the pattern of the used flora in Mexico, where the useful flora represents between 30 and 45% of the total (Caballero et al. 1998). That the number of species in the useful flora we registered in the COBIO (576 species) was considerably lower than that we recorded in the REBIOSH might be the consequence of the lower diversity of temperate zones compared to dry and humid tropical zones.

Of the total useful species, we recorded in the COBIO, 389 (67.63%) were native and 187 (32.47%) were exotic. Regarding growth habit, 301 (52.3%) species were herbs, 160 (27.8%) trees, 92 (16%) shrubs, and 12 (2.1%) species epiphytes, while the remaining species (1.9%) were climbers, rosettes, vines, and palms. We recorded in the COBIO, 399 (39.27%) plant species used for medicinal purposes, 79 (13.72%) as food, and 69 (11.98%) for ornamental purposes (Table 6).

Of the total species of useful plants, we recorded in the COBIO, 258 (44.8%) wild, 241 (41.8%) domesticated, 83 (14.4%) ruderal, and 18 (3.1%) weedy plants.

In the REBIOSH, 317 (55%) useful plant species are gathered wild plants obtained from natural or anthropized vegetation, 243 (42.2%) are cultivated, both by seed or vegetatively, and 17 (3%) are tolerated.

Use of Medicinal Plants in the Chichinautzin Biological Corridor

The more represented use category of plants in the COBIO was medicinal, as it was in the REBIOSH. However, in the former region that predominance appears to be due to the high percentage of indigenous people and the use of traditional medicine for first-level health care (Monroy-Ortiz and Monroy 2010), rather than to ecological predominance or intensive trade of medicinal plants as in the latter zone.

Another probable reason for the high number of medicinal plant species in the COBIO could be the abundance of medicine men and women (curanderos), bonesetters (hueseros), healers (sanadores), herbalists, and other professional traditional medical practicioners. This fact has generated the proliferation of traditional medicine tourism in the region – particularly since the Mexican government’s tourism ministry assigned Tepoztlán the category of Pueblo Mágico, an assignment meant to favor regional tourism in indigenous and high biocultural richness. Consequently, temascals, massage spas, and many traditional medic offices have been established in the region, which offer services to national and foreign patients (Ruiz-López and Alvarado-Rosas, 2017).

Threats to the Traditional Knowledge About Plants in the COBIO

Despite the current importance of plants in the life of the inhabitants of the COBIO, several threats exist to the traditional knowledge about plants. These threats might have negative impacts for conservation of natural vegetation and traditional agroecosystems like milpas and homegardens.

Maybe, one of the strongest pressures on the traditional knowledge of plants in the COBIO could be land use change, which between 1973 and 2000 caused a 35% reduction of forest covers in the region, mostly due to the expansion of urban areas and agriculture (CONANP 2003). Because the northern portion of the state of Morelos is adjacent to Mexico City, land is highly attractive for the real estate markets. Consequently, it is frequent that illegal loggers and organized crime groups – in collusion with corrupt local authorities – promote forest fires with the purpose of favoring the urbanization of forest areas (López-Portillo-Vargas and Corral-Torres 2021).

Deforestation modifies people’s habits by decreasing activities like plant gathering for several purposes, or by restricting these activities to the elder population (Ayala-Enríquez et al. 2020), while the loss of agricultural land changes household’s feeding habits by increasing the consumption of processed foodstuffs; a tendency occurring not only in the COBIO but throughout Mexico (Bertran-Vilá 2005). The study made by Tegoma-Coloreano (2019) in the community of Tres Marías – located within the COBIO – shows the deep consequences of the loss of natural vegetation and agroecosystems in the transmission of knowledge about medicinal plants to children. The author found that 11-year-old children in Tres Marías have less knowledge of the medicinal flora in their community than their parents and grandparents. Children do not know the plants occurring in their surroundings, and – maybe because of the influence of the media and school inputs little related to their ecological and cultural contexts – have more knowledge about exotic than about native plants. She also documented that the transmission of knowledge to children in the community is mostly vertical, but also acknowledges a growing trend of the transversal and horizontal transmission of information.

The study of Villalpando-Toledo (2020) in the home gardens of Tepoztlán, Morelos, is another example of how land use changes modify traditional knowledge and practices. The author documented how tourism in Tepoztlán has become a strong change agent in the modification in composition and structure of the local home gardens. Many homegardens, until 20 years ago, were sources of edible and medicinal plants and, nowadays, have been transformed to parking lots or restaurant gardens and terraces dominated by ornamental plants (Fig. 6).

Changes in land use and cultural patterns modify the landscapes and homegardens in the Chichinautzin Biological Corridor (COBIO). (a) Progress of the urbanization in Tres Marías, Morelos, Mexico; (b) traditional milpa in Tres Marías, Morelos, Mexico; (c) and (d) homegardens in Tepoztlán, Morelos, Mexico. Some homegardens specilialized in aromatic and medicinal plants, others in edible plants; (e) and (f) the change in the homegardens is notorious, since ornamental plants are currently the dominant elements in these agroecosystems. (Photos: (a), (b), and (f) Araceli Tegoma Coloreano; (c), (d), and (e) María Idalia Villalpando Toledo)

Land use changes might also accelerate other multifactorial processes like the abandonment of primary activities, migration, and loss of contact with the surrounding environment (Benz et al. 2000); these factors representing strong pressures that threaten the persistence of the traditional knowledge about plants in the COBIO pose a challenge for the compilation of a multidisciplinary agenda aiming at reversing this trend.

Therefore, it is important to recognize that traditional knowledge is part of a biocultural heritage, which is strongly threatened, and measures should be taken for its protection. Some of them include: the incorporation in basic level schools of alternative forms of learning that encourage children’s contact with the surrounding environment. The ethnobotanical walks would not only allow the recognition of the plants, animals, and fungi that are distributed in the area, it is also a mode of coexistence with parents and grandparents, which strengthens social relationships and would help improve the deteriorated social environment.

Another measure should aim at the conservation of homegardens, milpas, and other agroecosystems as providers of food in villages and cities. Efforts should be made to generate exchanges of successful experiences, where homegardens, in addition to being seen as productive units, can also serve as places of learning, experimentation, and communitarian coexistence.

Conclusions

The information we systematized show that the REBIOSH and COBIO mountain zones of the state of Morelos, Mexico, harbor high biocultural richness that expresses in the local people’s ample knowledge about the use and management of native and exotic plants. In both regions, we documented the preponderance of the ethnobotanical knowledge about the medicinal use of plants, which in each region is due to different ecological, historical, and cultural factors.

However, our results also show that we are yet far from completing the information about the useful flora in the REBIOSH. Therefore, more research needs to be made in the region to document processes beyond use, such as plant resource management and the factors affecting its temporal dynamics.

Finally, in both regions, the persistence of the local ethnobotanical knowledge is threatened by strong pressures driven by local cultural change, which is frequently amplified by social phenomena like migration and land use changes.

Our work in the main mountain zones of the state of Morelos should be seen as a first effort to compile information, and to find documentation voids, vulnerabilities, and pending research tasks. Our results might facilitate the building of an agenda to visualize the local traditional knowledge and practices at the regional level, aiming at establishing biocultural conservation priorities.

References

Abad-Fitz I, Maldonado-Almanza B, Aguilar-Dorantes K, Sánchez-Méndez L, Gómez-Caudillo L, Casas A, Blancas J, García-Rodríguez Y, Beltrán-Rodríguez L, Sierra-Huelsz JA, Cristians S, Moreno-Calles AI, Torres-García I, Espinosa-García FJ. Consequences of traditional management in the production and quality of copal resin (Bursera bipinnata (Moc. & Sessé ex DC.) Engl.) in Mexico. Forests. 2020;11(9):991. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11090991.

Albuquerque UP. Implications of ethnobotanical studies on bioprospecting strategies of new drugs in semi-arid regions. The Open Complementary Medicine Journal. 2010;2:21–3. https://doi.org/10.2174/1876391X01002010021.

Argueta A. El estudio etnobiológico de los tianguis y mercados en México. Etnobiología. 2016;14(2):38–46.

Arjona-García C, Blancas J, Beltrán-Rodríguez L, López Binnqüist C, Colín H, Moreno-Calles AI, Sierra-Huelsz JA, López-Medellín X. How does urbanization affect perceptions and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants? J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2021;17:48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-021-00473-w.

Ayala-Enríquez MI, Maldonado-Almanza B, Blancas J, Román-Montes de Oca E, García-Lara F. Panorama general de la flora medicinal. In: CONABIO, editor. La biodiversidad en Morelos. Estudio de Estado 2. Vol. III. Ciudad de México: CONABIO; 2020. p. 69–76.

Beltrán-Rodríguez L. Estructura, dinámica poblacional y regeneración del leño de Amphipterygium adstringens (Anacardiaceae) en el ejido El Limón, Morelos, México. PhD thesis. Colegio de Postgraduados; 2018.

Beltrán-Rodríguez L, Manzo-Ramos F, Maldonado-Almanza B, Martínez-Ballesté A, Blancas J. Wild medicinal species traded in the Balsas basin, Mexico: risk analysis and recommendations for their conservation. J Ethnobiol. 2017;37(4):743–64. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-37.4.743.

Beltrán-Rodríguez L, Valdez-Hernández JI, Saynes-Vásquez A, Blancas J, Sierra-Huelsz JA, Cristians S, Martínez-Ballesté A, Romero-Manzanares A, Luna-Cavazos M, de la Rosa MA B, Pineda-Herrera E, Maldonado-Almanza B, Ángeles-Pérez G, Ticktin T, Bye R. Sustaining medicinal barks: survival and bark regeneration of Amphipterygium adstringens (Anacardiaceae), a tropical tree under experimental debarking. Sustainability. 2021a;13:2860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052860.

Beltrán-Rodríguez L, Cristians S, Bye R. Las cortezas como productos forestales no maderables en México: Análisis nacional y recomendaciones para su aprovechamiento sostenible. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 2021b.

Benz B, Cevallos J, Santana F, Rosales J, Graf S. Losing knowledge about plant use in Sierra de Manantlan Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Econ Bot. 2000;54(2):183–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02907821.

Bertran-Vilá M. Cambio alimentario e identidad de los indígenas mexicanos. Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 2005.

Blancas J, Casas A, Pérez-Salicrup D, Caballero J, Vega E. Ecological and socio-cultural factors influencing plant management in Náhuatl communities of the Tehuacán Valley, Mexico. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9(39) https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-39.

Blancas J, Beltrán-Rodríguez L, Maldonado-Almanza B, Sierra-Huelsz JA, Sánchez L, Mena-Jiménez F, García-Lara F, Abad-Fitz I, Valdez-Hernández JI. Comercialización de especies arbóreas utilizadas en medicina tradicional y su impacto en poblaciones silvestres. In: CONABIO, editor. La biodiversidad en Morelos. Estudio de Estado 2. Vol. III. Ciudad de México: CONABIO; 2020. p. 215–23.

Bolongaro A, Torres V. El clima como integrador de ecosistemas. In: CONABIO. La biodiversidad en Morelos. Estudio de Estado 2. Volumen I. Ciudad de México: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad; 2020.

Bonilla-Barbosa JR, Villaseñor JL. Catálogo de la flora del estado de Morelos. Cuernavaca: Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2003.

Caballero J, Casas A, Cortés L, Mapes C. Patrones en el conocimiento, uso y manejo de plantas en pueblos indígenas de México. Estudios Atacameños. 1998;16:181–95.

CONANP. Estimación de la tasa de transformación del hábitat en el “Corredor Biológico Chichinautzin”. Periodo 1973–200. Informe final. Ciudad de México: Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas – Fondo Mexicano para la Conservación de la Naturaleza A.C; 2003. https://simec.conanp.gob.mx/TTH/Chichinautzin_Zempoala_Tepozteco/Chichinautzin_Zempoala_Tepozteco_TTH_1973_2000.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2022.

CONANP. Programa de Conservación y Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra de Huautla. Ciudad de México: Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas; 2005.

CONEVAL (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social). Informe de pobreza y evaluación. Morelos. Ciudad de México: CONEVAL; 2020.

Corona E. Escenarios paleobiológicos para las interacciones entre las sociedades y el medio ambiente en la región de Morelos. In: López-Varela SL, editor. La arqueología en Morelos: dinámicas sociales sobre las construcciones de la cultura material. Tomo II. Cuernavaca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2018. p. 31–42.

Crespo H. Los inicios de la agroindustria azucarera en la región de Cuernavaca y Cuautla. In: Crespo H, editor. Historia de Morelos. Tierra, gente, tiempos del Sur. Tomo III. Cuernavaca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2018. p. 739–66.

Cristians S, Guerrero-Analco JA, Pérez-Vásquez A, Palacios-Espinosa F, Ciangherotti C, Bye R, Mata R. Hypoglycemic activity of extracts and compounds from the leaves of Hintonia standleyana and H. latiflora: potential alternatives to the use of the stem bark of these species. J Nat Prod. 2009;72(3):408–13. https://doi.org/10.1021/np800642d.

Cruz A, Salazar ML, Campos OM. Antecedentes y actualidad del aprovechamiento de copal en la Sierra de Huautla, Morelos. Revista de Geografía Agrícola. 2006;37:97–116.

Delgado-Lemus A, Torres I, Blancas J, Casas A. Vulnerability and risk management of Agave species in the Tehuacán Valley, México. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-53.

Diario Oficial de la Federación. Decreto por el que se declara el área de protección de flora y fauna silvestre, ubicada en los municipios de Huitzilac, Cuernavaca, Tepoztlán, Jiutepec, Tlalnepantla, Yautepec, Tlayacapan y Totolapan, Morelos. Órgano del Gobierno Constitucional de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. 1988;CDXXII(22):27–48.

Escandón-Calderón J, Ordoñez-Díaz JAB, Nieto MC, Ordóñez-Díaz MJ. Cambio en la cobertura vegetal y uso del suelo del 2000 al 2009 en Morelos, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales. 2018;9(46):27–53. https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v9i46.135.

Flores-Castorena A, Martínez-Alvarado D. Sinopsis florística. In: Bonilla-Barbosa JR, Mora VM, Luna-Figueroa J, Colín H, Santillán-Alarcón S, editors. Biodiversidad, conservación y manejo en el Corredor Biológico Chichinautzin. Condiciones actuales y perspectivas. Cuernavaca: Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2010. p. 69–97.

García E. Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de Köppen (para adaptarlo a las condiciones de la República Mexicana). Ciudad de México: Instituto de Geografía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 1988.

García J. Hernán Cortés empresario: el papel económico Cuauhnáhuac en las empresas cortesianas. In: Crespo H, editor. Historia de Morelos. Tierra, gente, tiempos del Sur. Tomo III. Cuernavaca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2018. p. 648–713.

Garza S, Palavicini B. Xochicalco. La serpiente emplumada y Quetzalcóatl. Arqueología Mexicana. 2002;53:42–5. https://arqueologiamexicana.mx/mexico-antiguo/xochicalco-la-serpiente-emplumada-y-quetzalcoatl. Accessed 23 Apr 2022.

González-Insuasti MS, Martorell C, Caballero J. Factors that influence the intensity of non-agricultural management of plant resources. Agrofor Syst. 2008;74(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-008-9148-z.

Grove DC. Chalcatzingo. Excavations on the Olmec Frontier. Hungary: Thames and Hudson; 1984.

Hersch-Martínez P. Actores sociales de la flora medicinal en México. Revista de la Universidad de México. 2003;629:30–6.

Hersch-Martínez P. Plantas medicinales silvestres del suroccidente poblano y su colindancia en Guerrero, México: Rutas de comercialización, antecedentes y dinámica actual. In: Long J, Attolini A, editors. Caminos y mercados de México: por los caminos del sur. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas-UNAM; 2010. p. 665–86.

INAH. Zona Arqueológica Teopanzolco. 2022. https://www.inah.gob.mx/zonas/127-zona-arqueologica-tepozteco. Accessed 25 Jun 2022.

INAH. Zona Arqueológica Tepozteco. 2022. https://www.inah.gob.mx/zonas/127-zona-arqueologica-tepozteco. Accessed 16 Jun 2022.

INECC. Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático. Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Corredor Biológico Chichinautzin. http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones2/libros/2/chichinau.html. Accessed 25 Jun 2022.

INEGI. Panorama sociodemográfico de Morelos. In: Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. 2021. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/nueva_estruc/702825197896.pdf. Accessed 30 october 2022.

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022. https://www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed on 21 Mar 2022.

Juárez-Mondragón A. Prácticas de aprovechamiento en unidades de manejo para la conservación de la vida silvestre (UMA) del sur de Morelos. Cuernavaca: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro Regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias; 2019.

Linares E, Bye R. El copal en México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Biodiversitas. 2008;78:8–11.

Linares E, Bye R. La dinámica de un mercado periférico de plantas medicinales de México: el tianguis de Ozumba, Estado de México, como centro acopiador para el mercado de Sonora (mercado central). In: Long J, Attolini A, editors. Caminos y mercados de México: por los caminos del sur. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas-UNAM; 2010. p. 631–64.

López-Portillo-Vargas A, Corral-Torres Y. 2021. Atención a un incendio forestal en el Parque Nacional Lagunas de Zempoala, Morelos. Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Parque Nacional Lagunas de Zempoala Informe final SNIB-CONABIO, proyecto No. TR002. Ciudad de México: CONANP; 2021. http://www.conabio.gob.mx/institucion/proyectos/resultados/InfTR002.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Maderey LE. Evapotranspiración real en Hidrogeografía IV.6.6. Atlas Nacional de México. Vol. II Escala 1 4000000. Instituto de Geografía UNAM. México. 2002. http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/metadata/gis/evapr4mgw.xml?_httpcache=yes&_xsl=/db/metadata/xsl/fgdc_html.xsl&_indent=no. Accessed 27 Jul 2022.

Maldonado B. Aprovechamiento de los recursos florísticos de la Sierra de Huautla, Morelos, México. MSc thesis. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 1997.

Maldonado B. Patrones de uso y manejo de los recursos florísticos del Bosque Tropical Caducifolio en la Cuenca del Balsas, México. PhD thesis. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 2013.

Maldonado D. La producción agrícola en el Morelos prehispánico. In: Crespo H, editor. Historia de Morelos. Tierra, gente, tiempos del Sur. Tomo III. Cuernavaca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2018. p. 115–37.

Maldonado B, Caballero J, Delgado-Salinas A, Lira R. Relationship between use value and ecological importance of floristic resources of seasonally dry tropical forest in the Balsas River Basin, Mexico. Econ Bot. 2013;67(1):17–29.

Mena F. Estrategias ecológicas y culturales para garantizar la disponibilidad de Productos Forestales No Maderables en la Selva Baja del sur de Morelos. MSc Thesis. Cuernavaca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2018.

Monroy-Ortiz C, Castillo-España P. Plantas medicinales utilizadas en el estado de Morelos. Cuernavaca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2007.

Monroy-Ortiz C, Monroy R. Plantas medicinales utilizadas en el COBIO: listado preliminar. In: Bonilla-Barbosa JR, Mora VM, Luna-Figueroa J, Colín H, Santillán-Alarcón S, editors. Biodiversidad, conservación y manejo en el Corredor Biológico Chichinautzin. Condiciones actuales y perspectivas. Cuernavaca: Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2010. p. 211–28.

Parodi BG. La exploración botánica del doctor Francisco Hernández en el Marquesado del Valle (1573). In: Goldsmit S, Lozano R, editors. España y Nueva España: sus acciones transmarítimas. Memorias del I Simposio Internacional. Ciudad de México: Universidad Iberoamericana; 1991. p. 39–70.

Phillips O, Gentry AH. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: II. Additional hypothesis testing in quantitative ethnobotany. Econ Bot. 1993;47:33–43.

Ramírez R, Ocampo F, Rojas B, Flores G, Tovar E, Sánchez A. Flora arbórea no nativa, un potencial riesgo para la biodiversidad. In: CONABIO, editor. La biodiversidad en Morelos. Estudio de Estado 2. Volumen III. Ciudad de México: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad; 2020.

Ruiz-López CF, Alvarado-Rosas C. Los falsos escenarios turísticos y la reconfiguración del territorio en Tepoztlán, Morelos. El Periplo Sustentable. 2017;33:291–329.

SADER. Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Arroz a la mexicana, sólo el de Morelos ¡sí señor! 2021. https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/articulos/arroz-a-la-mexicana-solo-el-de-morelos-si-senor. Accessed 27 Jul 2022.

Santillán-Alarcón S, Sorani-Dalbón V, Bonilla-Barbosa JR, Luna-Figueroa J, Colín H. Escenario Geográfico. In: Bonilla-Barbosa JR, Mora VM, Luna-Figueroa J, Colín H, Santillán-Alarcón S, editors. Biodiversidad, conservación y manejo en el Corredor Biológico Chichinautzin. Condiciones actuales y perspectivas. Cuernavaca: Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2010. p. 3–20.

Semo A. El ferrocarril en México (1880–1900). Tiempo, espacio y percepción. Ciudad de México: Centro Nacional para la Preservación del Patrimonio Cultural Ferrocarrilero; 2020.

SIMEC (Sistema de Información, Monitoreo y Evaluación para la Conservación). Corredor Biológico Chichinautzin. Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas. https://simec.conanp.gob.mx/ficha.php?anp=39®=7. Accessed 27 Jul 2022.

Solares F, Díaz V, Boyás JC. Avances del estudio sobre efecto del descortezamiento en la capacidad de regeneración de corteza de cuachalalate (Amphipterygium adstringens Schiede ex Schlecht.) en el estado de Morelos. Memoria INIFAP-SARH. Campo Experimental “Zacatepec” Publicación especial. 1992;7:91–8.

Solares F, Vázquez JMP, Gálvez MC. Canales de comercialización de la corteza de cuachalalate (Amphipterigium adstringens Schiede ex Schlecht.) en México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales. 2012;3(12):29–42.

Soto-Nuñez J, Sousa M. Plantas Medicinales de la Cuenca del Río Balsas. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Biología-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 1995.

Tegoma-Coloreano A. Factores que afectan la transmisión del conocimiento de la flora medicinal entre generaciones: estudio de caso en Tres Marías, Morelos, México. Bachelor thesis. Cuernavaca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2019.

Toledo V, Barrera-Bassols N, García-Frapolli E, Alarcón-Chaires P. Uso múltiple y biodiversidad entre los Mayas yucatecos (México). Interciencia. 2008;33(5):345–52.

Trujillo ML, López-Medellín X. ¿Qué es la conservación desde el punto de vista de los campesinos? Condiciones productivas en un área natural protegida, Morelos, México. Etnobiología. 2018;16(1):58–72.

Villalpando-Toledo MI. Cambio cultural y su impacto en la estructura y composición de los huertos familiares de Tepoztlán, Morelos. MSc thesis. Cuernavaca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2020.

Zolla C. Epidemias, epidemiologías y herbolaria medicinal en el Morelos del siglo XVI. In: Crespo H, editor. Historia de Morelos. Tierra, gente, tiempos del Sur. Tomo III. Cuernavaca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos; 2018;309–354.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank financial support from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT), Mexico (research projects 271837, 280901, 293914, 299274, 299287, 318799).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry

Blancas Vázquez, J.J. et al. (2023). Ethnobotanical Knowledge and the Patterns of Plant Use and Management in the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve and the Chichinautzin Biological Corridor in Morelos, Mexico. In: Casas, A., Blancas Vázquez, J.J. (eds) Ethnobotany of the Mountain Regions of Mexico. Ethnobotany of Mountain Regions. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99357-3_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99357-3_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-99356-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-99357-3

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesReference Module Biomedical and Life Sciences