Abstract

The study explored the usefulness of Islamic work ethics within the context of public sector information technology projects. Using social learning theory and social exchange theory, we examined the trickle-down impact of leader’s Islamic work ethics on project performance via teamwork quality. Data were collected from 188 project managers leading information technology teams. Discriminant validity of constructs was established using confirmatory factor analysis, while hypotheses were tested using SPSS process macro. Statistical analysis showed that Islamic work ethics positively and significantly impacted project performance. Teamwork quality partially mediates the relationship between Islamic work ethics and project performance. Public organizations should develop training programs to enlighten employees about the fundamentals of work practices from the Islamic perspective.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Islamic work ethics

- Teamwork quality

- Team performance

- Information technology

- Trickle-down effect

- Social influence theories

1 Introduction

Work ethics has always remained an essential discussion issue for organizational scholars (Wasieleski & Weber, 2019). The focus on ethics from an Islamic perspective has emerged over the past few years (Khan et al., 2015; Murtaza et al., 2016). The concept of Islamic work ethics has its roots in the teachings of the Quran and the Prophet Muhammed (SAW). Islamic work ethics characterize a collection of work-related moral principles and values that differentiate between right and wrong in Islam’s context (Beekun, 1997). Previous literature has reported significant effects of Islamic work ethics on an individual’s attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (e.g., de Clercq et al., 2019; Gheitani et al., 2019; Haroon et al., 2012). However, no considerable research has been conducted to examine the influence of a leader’s Islamic work ethics on team-level outcomes within public-sector organizations.

The current study’s objective is to analyze the direct and indirect effect of a leader’s Islamic work ethics on the performance of public-sector information technology (IT) projects. In terms of direct effect, we explore the role of a leader’s Islamic work ethics in fostering the performance of IT projects delivered by public-sector organizations. In terms of indirect effect, we introduce teamwork quality as a mediating team-level mechanism through which the leader’s Islamic work ethics affects the IT team’s project performance. Following Hoegl and Gemuenden (2001), we conceptualize teamwork quality as the quality of interactions between team members during the planning, execution, and completion of a project. Interaction refers to the connectedness or the “being in contact” of two or more people and the quality of collaborative work performed by team members (Campion et al., 1993).

In the current investigation, we contribute to Islamic business ethics literature related to public administration. First, we assess the critical premise of Islamic work ethics that strives to develop a positive and moral workplace environment and prioritize cooperating and collaborating with others (Ahmad, 2011; Aldulaimi, 2016; Ali, 1988). Within the public sector context, helpful task interaction between employees is a fundamental ingredient of creating successful community products and services. We understand that organizations’ digital initiatives and e-governance mechanisms are increasingly common in developing and developed countries (Danish, 2006; Glyptis et al., 2020). Thus, in this regard, our study aims to contribute to the usefulness and effectiveness of the leader’s Islamic work ethics on the quality of IT projects developed by the public sector. Second, we explore the top-down effect of the leader’s Islamic work ethics via the mediating impact of Islamic work ethics on team-level performance. Examining the trickle-down effect of the leader’s Islamic ethical principles as a social influence process to accomplish team success is one step toward validating the theory of Islamic work ethics. The following section reviews the literature on Islamic work ethics, followed by developing the study hypothesis.

2 Literature on Islamic Work Ethics

Islamic work ethics is defined as the extent to which employees embrace Islamic ethical values in their daily work activities (Ali, 1988; De Clercq et al., 2019). Muslims live their daily lives, including the decisions they make at work, such that actions in the workplace are judged through the lens of these religious values (Ali & Al-Owaihan, 2008). Islamic work ethics emphasizes diligent effort, collaboration, and morally responsible conduct in performing job tasks (Ali & Al-Owaihan, 2008). The seminal work on Islamic work ethics comes from Ali and Al-Owaihan (2008), who integrated Islamic and organizational literature, suggested four pillars of Islamic work ethics: effort, competition, transparency, and morally responsible conduct. Empirical studies have shown significant main effects of IWE on an individual’s attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Within the Islamic banking sector, Hayati and Caniago (2012) found that individuals with a strong inclination and awareness about Islamic work ethics are delighted with their job and possess strong affective commitment toward their organization. Abu-Saad (2003) empirically studied Islamic work ethics among Arab educators in Israel and found that high Islamic work ethics predicts the importance of one’s contribution to society. Conducting the study within Malaysian public sector organizations, Kumar and Rose (2012) examined the moderating effect of the Islamic work ethics on knowledge-sharing enablers and the innovation capability of employees in Malaysia. They found that the Islamic work ethics significantly moderated the relationship between knowledge-sharing capacity and innovation capability. In a recent study conducted within public sector educational institutions, Murtaza et al. (2016) demonstrated that Islamic work ethics significantly positively affected extra-role work behaviors, including organizational citizenship behavior and knowledge-sharing behavior.

Similarly, De Clercq et al. (2019) collected data from multiple industries (e.g., construction, finance, and education). They showed that Islamic ethical values buffer the negative relationship between high family-to-work conflict and helping behavior. The negative relationship becomes weaker in the presence of high Islamic work ethics. A sample of Royal Malaysian Air Force, Husin and Kernain (2019), showed the influence of individual behavior and organizational commitment toward enhancing Islamic work ethics. Thus, it appears that there is a recent surge in the studies of Islamic work ethics, which have primarily focused on its relationship at the individual (within-person) level, highlighting the need to examine associations between Islamic work ethics and team-level outcomes. While there has been some evidence on Islamic work ethics’ utility within public sector firms, its effectiveness within team-based public IT organizations remains unexplored.

The ethical work practices within public-sector organizations may be more critical than private-sector organizations. Public organizations serve the masses and work for community welfare through the public’s monetary and administrative resources (Goh & Arenas, 2020). Notably, any democratic government’s success in accomplishing welfare and development goals largely relies on public servants’ attitudes and behaviors (Anderson & Henriksen, 2005; Twizeyimana & Andersson, 2019). Governments worldwide strive to focus on e-governance and digitalization of their products and services (Ajmal et al., 2010; Heeks, 2003b). Public sector reforms in various countries have pressurized public organizations to be more transparent, ethical, practical, and market-oriented—in sum, to be more business-like (Glyptis et al., 2020). The existing literature on Islamic work ethics captures its value within organizations. However, this research has not adequately explored why and how Islamic-oriented work practices play a role in efficient government products and services.

3 Hypothesis

3.1 Islamic Work Ethics and Team Performance: A Social Influence Process

We rely on social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) and social exchange theory (Blau, 1986) to explain why and how a leader’s Islamic work ethics facilitates IT project team performance via teamwork quality and meaning in life. According to social learning theory, individuals learn by modeling the attitudes, values, and behaviors of role models in their environment (Bandura, 1977; Brown & Treviño, 2014). Team members often desire to mimic their team leader’s morals and behavior (Brown & Treviño, 2014; Sendjaya et al., 2019), which is more likely if leaders are viewed as ethical role models. Team leaders possessing Islamic moral values are likely to be reliable role models because of their morally and professionally responsible conduct in performing workplace obligations (Aldulaimi, 2016; Ling et al., 2016). Consequently, a leader’s ethical work practices may be acquired by team members (Brown & Treviño, 2014) and reciprocated through the process of social exchange in which team members display productive interaction and cooperative behavior toward each other in accomplishing project goals (Blau, 1986; Sendjaya et al., 2019).

We expect a direct connection between leader Islamic work ethics and IT project team performance. Within team settings, the leader’s role is to create an environment that facilitates collective team effort and improves team functionality toward achieving objectives (Chen et al., 2015). If a leader practices Islamic work ethics, then there is a likelihood that team members will show cooperation and consultation at work and strictly forbid anyone from engaging in harmful and offensive behavior (Yousef, 2001). A leader’s Islamic work ethics will discourage team members from dishonesty and laziness in performing job tasks and encourage volunteerism and helping behavior (Khan et al., 2015; Yousef, 2000). This is consistent with the Quran teachings, which promote responsible, productive, and creative behavior in the marketplace (2: 275; 25: 67; respectively): “Those who, when spending, are not extravagant and not niggardly, but hold a just (balance) between those (extremes),” and “Those who hoard gold and silver and spend not in the way of God: announce unto them a most grievous chastisement.” Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

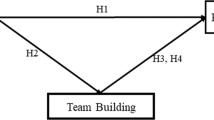

Hypothesis 1: Leader’s Islamic work ethics has a positive and direct relationship with team task performance.

3.2 Islamic Work Ethics, Teamwork Quality, and Team Performance

In the present study, we follow the conceptualization of teamwork quality extended by Hoegl and Gemuenden (2001), later followed by Hoegl (2005) and Lindsjørn et al. (2016). They presented a comprehensive teamwork quality construct as a composite measure of six underlying facets: communication, coordination, balance of team member’s contribution, mutual support, effort, and cohesion. Communication is the exchange of information among team members (Pinto & Pinto, 1990). Coordination is the degree of shared understanding regarding task interdependence and the extent of individual contributions toward collective tasks (Butchibabu et al., 2016). The balance of member contributions is the fair and consistent contribution of each member toward accomplishing team objectives (Liao, 2017). Mutual support is the intensive collaboration of individuals that depends upon a cooperative rather than a competitive frame of mind (Becker et al., 2018). The effort is the norm of sharing workloads and prioritization of team’s goal over non-goal-related activities (Campion et al., 1993; Pinto & Pinto, 1990). Cohesion is the level of desire through which the team members want to remain a part of the team (Pescosolido & Saavedra, 2012).

Social learning theory argues that people can learn simply by observing and replicating others’ behavior, especially their role models. Team leaders are a significant source of role modeling due to their status and ability to utilize managerial rewards. Leaders can often establish what values and behaviors are expected in team functionality (Brown & Treviño, 2014; Sims & Brinkmann, 2002). Sitting at the top of the hierarchy, team leaders set the tone for the behaviors and work-related norms expected of team members (Chen et al., 2015). Recent research has shown that leader’s ethical and social service values often have a trickle-down effect on followers (Cheng et al., 2019; Peng & Wei, 2018; Sendjaya et al., 2019), which subsequently influences team functionality (Chiu & Chiang, 2019). Consistent evidence of top-down effects of leadership through follower modeling of leader behavior, as outlined in social learning theory, has been found in laboratory experiments (Sy et al., 2005) as well as field examinations (Mayer et al., 2009).

Team members emulate leaders’ moral values and behaviors because leaders often serve as mentors to their followers (Liden et al., 2014). Protégés often learn by imitating the work practices of their mentors (Lankau & Scandura, 2002). Team members are especially inclined to model leader behaviors when they perceive the leader as possessing desirable qualities (Peng & Wei, 2018). Leaders high in Islamic work ethics have many attractive characteristics for team members. The qualities such as commitment to job responsibilities, cooperation with colleagues, fair competition, and hard work embodied with Islamic work ethics will be desirable for teams (Ali & Al-Owaihan, 2008). In social exchange, such qualities inspire team members to display high teamwork quality useful for team performance (Hoegl & Gemuenden, 2001). Because of the team leader’s high moral and social values, each team member will begin to understand the importance of communication, coordination, and mutual support in successfully performing tasks. When a team is led by an individual inclined toward hard work and effort and building a community environment at the workplace, it encourages the entire team to improve their teamwork quality. A leader’s Islamic work ethics will enhance mutual collaboration and support rather than competition within groups (Khan et al., 2015), allowing the entire unit to work through different phases of team life effectively. Thus, we expect that:

-

Hypothesis 2: Leader’s Islamic work ethics has a positive and direct relationship with teamwork quality.

The teamwork quality construct provides a comprehensive measure of the collaborative team-task process focusing on the quality of interactions rather than on teams (Hoegl, 2005; Hoegl & Gemuenden, 2001). Each team member must maintain coordination and communication within the team environment and provide a helping hand to other team members when performing collective tasks (Maynard et al., 2018). Because team tasks are often interdependent, each team member must work on their job and help other team members complete their subtasks (Pescosolido & Saavedra, 2012). Further, the interdependence of tasks requires that each team member understand each subtask’s timelines and priorities. Such understanding will only develop when team members plan, communicate, and synchronize their actions (Lindsjørn et al., 2018). Previous research has shown that teamwork quality is a determinant of team performance (Dayan & Di Benedetto, 2009; Lindsjørn et al., 2018). Thus, we propose that:

-

Hypothesis 3: Teamwork quality has a positive and direct relationship with team performance.

-

Hypothesis 4: Teamwork quality mediates the relationship between Islamic work ethics and team performance.

4 Method

We approached the state government-operated information technology board in the largest province (by population) of Pakistan. This public sector body works through project teams who plan, develop, and deliver various applications, software, and websites as part of the government’s e-governance and digitalization initiatives. We employed a multi-wave survey design to collect data from project managers. At Time 1, project managers were asked to rate their Islamic work ethics and teamwork quality in the ongoing project. Project managers also provided their necessary demographic information, including education, experience, and gender. At Time 2, team leaders rated the performance of their ongoing project. Because the research was aimed at Islamic work ethics, we ensured that all the participants are Muslims. Participation was voluntary, and complete anonymity was guaranteed for all participants.

In total, 238 project managers were invited to respond to the current research study. We received responses from 197 project managers. However, we retained only those project managers who responded at both Time 1 and Time 2. The final sample comprised 188 project managers. The response rate was approximately 78%. About 40% of respondents had master’s degrees, 45% had a bachelor’s degree, and 15% had other technical certifications.

Seventy-nine percent of respondents were male, and 21% were female.

4.1 Measures

Islamic work ethics. Consistent with previous research (Khan et al., 2015; Murtaza et al., 2016), we used a 17-item Islamic work ethics scale developed by Ali (1988). Each item was anchored on 5 points ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale demonstrated adequate reliability (α = 0.86). A sample item measuring Islamic work ethics includes “Human relations in organizations should be emphasized and encouraged.”

Teamwork Quality

We adopted a standard instrument measuring six dimensions of teamwork quality developed by Hoegl and Gemuenden (2001). This scale had 37 items reflecting six aspects of teamwork quality: communication, coordination, the balance of member contributions, mutual support, effort, and cohesion. The team leader rated each team as a unit on all six dimensions. All items were anchored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The composite 37-item scale showed adequate reliability (α = 0.92). Six particular sample items representing each dimension includes “There was frequent communication within the team (communication), The work done on subtasks within the project was closely harmonized (coordination), The team members were contributing to the achievement of the team’s goals in accordance with their specific potential (balance of member contributions), The team members helped and supported each other as best they could (mutual support), Our team put much effort into the project effort (effort), and The team members were strongly attached to this project (cohesion).”

Team Performance

Team performance was measured using a 9-item scale developed by Ralf Müller (2008). This scale was previously used in several studies (e.g., Aga et al., 2016) and displayed satisfactory reliability (α = 0.90). Each item was ranked on five anchors ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item includes “We were able to manage and satisfy all project stakeholders with the project deliverables/outcome.”

Control variables

We included leader gender and education as control variables. Previous research has demonstrated the correlations between personal and demographic factors and individual ethical and moral values (Peterson et al., 2001).

4.2 Analyses

To test the direct and indirect effect hypothesis, we performed a mediation analysis (model 4, as described in the SPSS process macro) with bootstrap methods (Hayes, 2013). Preacher and Hayes developed an SPSS macro that facilitates estimation of the indirect effect ab, both with a standard theory approach (i.e., the Sobel test) and with a bootstrap approach to obtain confidence intervals (CIs). It also incorporates the stepwise procedure described by Baron and Kenny. Through the application of bootstrapped CIs, it is possible to avoid power problems introduced by asymmetric and other non-normal sampling distributions of an indirect effect (Edwards & Lambert, 2007; Mackinnon et al., 2004)

5 Results

The means, standard deviations, reliability coefficients, and intercorrelations among all the variables under study are shown in Table 1. As shown in the diagonal, all variables demonstrated acceptable relatabilities with alpha values above 0.70 (Nunnally, 1970).

5.1 Discriminant Validity of Constructs

We established the discriminant validity of constructs using the rigorous nested model method by Bagozzi and Phillips (1991). The results revealed that the unconstrained model had a χ2 of 3178.19 with 1378 degrees of freedom. In contrast, in which the correlation was constrained to 1, the constrained model had a χ2 of 3401.67 with 1379 degrees of freedom. The difference gives a χ2 of 223.48 with 1 degree of freedom and a p-value of <0.01. In conclusion, the χ2 test’s difference showed that constraining the correlation between the constructs to 1 did not improve model fit, supporting the conclusion that Islamic work ethics and teamwork quality represent two distinct constructs.

5.2 Model Testing

Table 2 presents the detailed results of the direct and mediation hypothesis. Supporting Hypothesis 1, we found a positive and significant unstandardized regression coefficient regarding the direct association between Islamic work ethics and team performance (B = 0.49, t = 6.05, p < 0.01). The bootstrapped direct effect further revealed that this relationship was positive and significant, with a 95% CI between 0.33 and 0.66. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was accepted. In support of Hypothesis 2, Islamic work ethics was positively associated with teamwork quality, as indicated by a positive and significant unstandardized regression coefficient (B = 0.60, t = 11.20, p < 0.01). Also, accepting Hypothesis 3, we found the positive and significant relationship between teamwork quality and team performance, controlling for Islamic work ethics (B = 0.36, t = 3.36, p < 0.01). Finally, a leader’s Islamic work ethics indirectly affected team performance via teamwork quality; this indirect effect was positive (0.22) with a 95% CI between 0.04 and 0.39, supporting Hypothesis 4. The formal two-tailed significance test (assuming a normal distribution) demonstrated that the indirect effect was significant (Sobel z = 3.15, S.E. = 0.06, p < 0.01).

6 Discussion

The study contributes to business ethics literature within the public sector domain by examining the trickle-down effect of the leader’s Islamic work ethics on team performance via teamwork quality. The limited research on leaders’ Islamic ethical values within the public sector and team context are somewhat surprising when project-based IT initiatives are increasingly common. Drawing from social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) and social exchange theory (Blau, 1986), we showed that a project manager’s Islamic work ethic is instrumental in aiding project performance and facilitating teamwork quality. Among pioneering studies, Yousef (2001), Beekun (1997), and Ali (1988) discussed this construct more systematically by linking ethical work values with employees or organizational outcomes. We established the utility of Islamic work ethics for collective functionality and performance within government organizations.

In the e-government context, it has been observed that almost 15% of the e-initiatives are successful. However, 50% and the rest of 35% can be labeled as partial and complete failures, respectively (Heeks, 2008). Moreover, while underlining the critical success factors for any information and communication technology (ICT)-based initiative in the public sector, “management system and structure” holds significant value. In other words, the gap between the reality and idealized (designed) value of the management system, its practices, and hierarchy can help to define and predict ICT success in any public sector organization (Guha & Chakrabarti, 2014; Heeks, 2003a; Ranaweera, 2016). The literature argues that ICT in public sector institutions provides far-reaching benefits and value if implemented and adopted optimally (Glyptis et al., 2020). Apart from the technical aspects, managerial practices and behavior (Ajmal et al., 2010) and organizational structure (Anderson & Henriksen, 2005) take a strategic ICT implementation in public sector institutions. According to Twizeyimana and Andersson (2019), to drive public value and transform any public sector institute with support of ICT initiative requires administrative efficiency and ethical behavior and professionalism in the workforce. The ICT reform in public institutions eliminates most of the face-to-face interaction and reengineer decision-making chains. It still demands fairness, equality, and honesty in eliminating corruption, abuse of power, and maximizing institutional capabilities. In such a scenario, Islamic work ethics may play a significant role in accomplishing positive outcomes.

The role of leadership is highly significant in public organizations, especially those adopting team-based work designs. Team-based organizations mostly execute their primary work functions using teams (Burke & Morley, 2016). It is already well-documented that positive team leadership flows down the organizational and team hierarchy and creates positive work and team outcomes (Cheng et al., 2019; Peng & Wei, 2018; Sendjaya et al., 2019). Thus, we showed that a leader’s Islamic work ethics would positively trickle-down positively affect project performance. Within the team and public sector context, the Islamic work ethics of a leader will signal team members to place considerable emphasis on cooperation, consultation, commitment, and hard work at the workplace, leading team members to improve their task performance through high teamwork quality (Lindsjørn et al., 2016).

6.1 Practical Implications

Islam is the second-largest religion in the world. The Muslim population is the fastest-growing population and constitutes around 24.1% of the world’s population. A significant number of Muslims work in different public-sector industries across the globe. From developed to underdeveloped countries, we observe Muslim employees at various public organization levels (Mahadevan & Kilian-Yasin, 2017). The intense business competition requires a worldwide and diverse workforce to innovate new products and understand new markets. Multinational organizations encourage workplace diversity, offering employment to people from different demographics, national, and religious backgrounds (Howard et al., 2017). Therefore, public organizations should introduce training courses that enlighten individuals about Islamic work practices, especially within Muslim countries. Within a team environment, the project manager’s behaviors and attitudes are considered a critical success factor for teams. This research has provided evidence that Islamic work ethics builds a formidable social and task environment where individuals focus on accomplishing collective goals. Therefore, if managers want to improve teamwork quality and achieve performance goals, they should consider exercising ethical values and principles encapsulated in Islamic preaching.

6.2 Limitations and Future Research

Like any other social science research, there are few limitations of the study which should be addressed in future studies. In our time-lagged study, we managed to administer survey questionnaires from project managers at two different points during a project. However, getting responses from project managers only is a limitation of this study. There may be a difference in the perceived teamwork quality of team members and project managers. Thus, further studies may propose and test a multilevel model that collects team leaders and team members (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001). Second, both Islamic work ethics and teamwork quality were measured simultaneously at Time 1. Therefore, it is not easy to establish a causal relationship between Islamic work ethics and teamwork quality because of simultaneous measurement. Future research could focus on designing experimental studies within a team context to determine if Islamic work ethics causes teamwork quality and subsequent team performance.

Third, we did not account for the moderating factors or boundary conditions in our input-mediator-output framework. We know that moderating variables could magnify or minimize the strong relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Thus, future research could identify moderating variables that could influence the magnitude of associations between Islamic work ethics, teamwork quality, and team performance. For instance, it is possible that team members’ religiosity moderates the relationship between Islamic work ethics and team performance. That relationship becomes more substantial when a team member is high in religiosity rather than low. Fourth, this study on the Pakistani public sector projects’ data will be relevant to the team and cultural factors. Regarding the team factor, it would be interesting to explore the utility of Islamic work ethics within virtual teams (Hoch & Dulebohn, 2017). In long-distance or virtual teams, there is no direct and physical contact between leaders and team members. Therefore, team members may not see the leader and hence mimic their behavior and moral values. Regarding cultural factors, Pakistan is a collectivistic country with a strong emphasis on group harmony and success (Hofstede, 2001). Thus, future research could examine the relative importance of the project manager’s Islamic work ethics for team performance within western and eastern countries.

References

Abu-Saad. (2003). The work values of Arab teachers in Israel in a multicultural context. Journal of Beliefs and Values, 24, 39–51.

Ahmad, M. S. (2011). Work ethics: An Islamic prospective. Journal of Human Sciences, 8(1), 850–859. Retrieved from http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en

Aga, D. A., Noorderhaven, N., & Vallejo, B. (2016). Transformational leadership and project success: The mediating role of team-building. International Journal of Project Management, 34(5), 806–818.

Ajmal, M., Helo, P., & Kekäle, T. (2010). Critical factors for knowledge management in project business. Journal of Knowledge Management, 14(1), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271011015633

Aldulaimi, S. H. (2016). Fundamental Islamic perspective of work ethics. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 7(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-022014-0006

Ali, A. (1988). Scaling an Islamic work ethic. Journal of Social Psychology, 128(5), 575–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1988.9922911

Ali, A. J., & Al-Owaihan, A. (2008). Islamic work ethic: A critical review. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 15, 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527600810848791

Anderson, K. V., & Henriksen, H. Z. (2005). The first leg of E-government research. International Journal of Electronic Government Research, 1(4), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.4018/jegr.2005100102

Bagozzi, R. P., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393203

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Becker, W. J., Cropanzano, R., Van Wagoner, P., & Keplinger, K. (2018). Emotional labor within teams: Outcomes of individual and peer emotional labor on perceived team support, extra-role behaviors, and turnover intentions. Group and Organization Management, 43(1), 38–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601117707608

Beekun, R. I. (1997). Islamic business ethics. International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT).

Blau, P. M. (1986). Exchange and power in social life (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2014). Do role models matter? An investigation of role modeling as an antecedent of perceived ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(4), 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1769-0

Burke, C. M., & Morley, M. J. (2016). On temporary organizations: A review, synthesis and research agenda. Human Relations, 69(6), 1235–1258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715610809

Butchibabu, A., Sparano-Huiban, C., Sonenberg, L., & Shah, J. (2016). Implicit coordination strategies for effective team communication. Human Factors, 58(4), 595–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720816639712

Campion, M. A., Medsker, G. J., & Higgs, A. C. (1993). Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: Implications for designing effective work groups. Personnel Psychology, 46(4), 823–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17446570.1993.tb01571.x

Chen, Z., Zhu, J., & Zhou, M. (2015). How does a servant leader fuel the service fire? A multilevel model of servant leadership, individual self identity, group competition climate, and customer service performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038036

Cheng, K., Wei, F., & Lin, Y. (2019). The trickle-down effect of responsible leadership on unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Business Research, 102, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.044

Chiu, H. C., & Chiang, P. H. (2019). A trickle-down effect of subordinates’ felt trust. Personnel Review, 48(4), 957–976. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-01-2018-0036

Danish, D. (2006). The failure of e-government in developing countries: A literature review. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 26(7), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2006.tb00176.x

Dayan, M., & Di Benedetto, C. A. (2009). Antecedents and consequences of teamwork quality in new product development projects: An empirical investigation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 12(1), 129–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601060910928201

de Clercq, D., Rahman, Z., & Haq, I. U. (2019). Explaining helping behavior in the workplace: The interactive effect of family-to-work conflict and Islamic work ethic. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3541-3

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1

Gheitani, A., Imani, S., Seyyedamiri, N., & Foroudi, P. (2019). Mediating effect of intrinsic motivation on the relationship between Islamic work ethic, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in banking sector. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 12(1), 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMEFM-01-2018-0029

Glyptis, L., Christofi, M., Vrontis, D., Del Giudice, M., Dimitriou, S., & Michael, P. (2020). E-government implementation challenges in small countries: The project manager’s perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 152, 119880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119880

Goh, J. M., & Arenas, A. E. (2020). IT value creation in public sector: How IT-enabled capabilities mitigate tradeoffs in public organisations. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2019.1708821

Guha, J., & Chakrabarti, B. (2014). Making e-government work: Adopting the network approach. Government Information Quarterly, 31(2), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.11.008

Haroon, M., Zaman, H., & Rehman, W. (2012). The relationship between Islamic work ethics and job satisfaction in healthcare sector of Pakistan. International Journal of Contemporary Business Studies, 3(5), 6–12.

Hayati, K., & Caniago, I. (2012). Islamic work ethic: The role of intrinsic motivation, job satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Job Performance. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 65, 272–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.122

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Introduction_to_Mediation_Moderation_and.html?id=8YX2QwGgD8AC&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Heeks, R. (2003a). I government development projects fail.

Heeks, R. (2003b). Most e-government-for-development projects fail : How can risks be reduced? Institute for Development Policy and Management University of Manchester.

Heeks, R. (2008). eGovernment for development—Success and failure rates of eGovernnment projects in developing/transitional countries. Retrieved March 5, 2018, from Institute of Development Policy and Management website: http://www.egov4dev.org/success/sfrates.shtml

Hoch, J. E., & Dulebohn, J. H. (2017). Team personality composition, emergent leadership and shared leadership in virtual teams: A theoretical framework. Human Resource Management Review, 27(4), 678–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.12.012

Hoegl, M. (2005). Smaller teams-better teamwork: How to keep project teams small. Business Horizons, 48(3), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2004.10.013

Hoegl, M., & Gemuenden, H. G. (2001). Teamwork quality and the success of innovative projects: A theoretical concept and empirical evidence. Organization Science, 12(4), 435–449.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.br/books?id=w6z18LJ_1VsC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Culture’s+Consequences:+Comparing+Values,+Behaviors,+Institutions,+and+Organizations+Across+Nations&hl=en&ei=eOWZTcLPEKrXiALG7LCdCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=book-thumbnail&redir_esc=y#

Howard, T. L., Peterson, E. A., & Ulferts, G. W. (2017). A note on the value of diversity in organisations. International Journal of Management and Decision Making, 16(3), 187–195.

Husin, W. N. W., & Kernain, N. F. Z. (2019). The influence of individual behaviour and organizational commitment towards the enhancement of Islamic work ethics at Royal Malaysian Air force. Journal of Business Ethics, 166, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551019-04118-7

Khan, K., Abbas, M., Gul, A., & Raja, U. (2015). Organizational justice and job outcomes: Moderating role of Islamic work ethic. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(2), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1937-2

Krull, J. L., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2001). Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 36(2), 249–277. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06

Kumar, N., & Rose, R. C. (2012). The impact of knowledge sharing and Islamic work ethic on innovation capability. Cross Cultural Management, 19, 142–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527601211219847

Lankau, M. J., & Scandura, T. A. (2002). An investigation of personal learning in mentoring relationships: Content, antecedents, and consequences. Academy of Management Journal, 45(4), 779–790. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069311

Liao, C. (2017). Leadership in virtual teams: A multilevel perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 27(4), 648–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.12.010

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Liao, C., & Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1434–1452. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0034

Lindsjørn, Y., Bergersen, G. R., Dingsøyr, T., & Sjøberg, D. I. K. (2018). Teamwork quality and team performance: Exploring differences between small and large agile projects. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, 314, 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91602-6_19

Lindsjørn, Y., Sjøberg, D. I. K., Dingsøyr, T., Bergersen, G. R., & Dybå, T. (2016). Teamwork quality and project success in software development: A survey of agile development teams. Journal of Systems and Software, 122, 274–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2016.09.028

Ling, Q., Lin, M., & Wu, X. (2016). The trickle-down effect of servant leadership on frontline employee service behaviors and performance: A multilevel study of Chinese hotels. Tourism Management, 52, 341–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.008

Mackinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128.

Mahadevan, J., & Kilian-Yasin, K. (2017). Dominant discourse, orientalism and the need for reflexive HRM: Skilled Muslim migrants in the German context. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(8), 1140–1162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1166786

Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. (Bombie). (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.002.

Maynard, M. T., Kennedy, D. M., & Resick, C. J. (2018). Teamwork in extreme environments: Lessons, challenges, and opportunities. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(6), 695–700. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2302

Müller, R. (2008). Choosing and developing the right leadership styles for projects|APPEL knowledge services. ASK Magazine, 46–47. Retrieved from https://appel.nasa.gov/2008/01/01/choosing-and-developing-the-right-leadership-stylesfor-projects/

Murtaza, G., Abbas, M., Raja, U., Roques, O., Khalid, A., & Mushtaq, R. (2016). Impact of Islamic work ethics on organizational citizenship behaviors and knowledge-sharing behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(2), 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551014-2396-0

Nunnally, J. C. (1970). Introduction to psychological measurement. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1970-19724-000.

Peng, H., & Wei, F. (2018). Trickle-down effects of perceived leader integrity on employee creativity: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(3), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3226-3

Pescosolido, A. T., & Saavedra, R. (2012). Cohesion and sports Teams. Small Group Research, 43(6), 744–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496412465020

Peterson, D., Rhoads, A., & Vaught, B. C. (2001). Ethical beliefs of business professionals: A study of gender, age and external factors. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010744927551

Pinto, M. B., & Pinto, J. K. (1990). Project team communication and cross-functional cooperation in new program development. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 7(3), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/0737-6782(90)90004-X

Ranaweera, H. M. B. P. (2016). Perspective of trust towards e-government initiatives in Sri Lanka. Springerplus. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1650-y

Sendjaya, S., Eva, N., Robin, M., Sugianto, L., ButarButar, I., & Hartel, C. (2019). Leading others to go beyond the call of duty: A dyadic study of servant leadership and psychological ethical climate. Personnel Review, 49(2), 620–635. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-08-2018-0285

Sims, R. R., & Brinkmann, J. (2002). Leaders as moral role models: The case of John Gutfreund at Salomon brothers. Journal of Business Ethics, 35(4), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013826126058

Sy, T., Côté, S., & Saavedra, R. (2005). The contagious leader: Impact of the leader’s mood on the mood of group members, group affective tone, and group processes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.295

Twizeyimana, J. D., & Andersson, A. (2019). The public value of e-government—A literature review. Government Information Quarterly, 36, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.01.001

Wasieleski, D. M., & Weber, J. (2019). Business ethics. Emerald.

Yousef, D. A. (2000). The Islamic work ethic as a mediator of the relationship between locus of control, role conflict and role ambiguity—A study in an Islamic country setting. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15(4), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940010330966

Yousef, D. A. (2001). Islamic work ethic: A moderator between organizational commitment and job satisfaction in a cross-cultural context. Personnel Review, 30(2), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480110380325

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Siddiquei, A.N., Hussain, S., Asadullah, M.A., Asmi, F. (2022). E-Governance Projects in Public Organizations: The Role of Project Manager’s Islamic Work Ethics in Accomplishing IT Project Performance. In: Alserhan, B.A., Ramadani, V., Zeqiri, J., Dana, LP. (eds) Strategic Islamic Marketing. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98160-0_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98160-0_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-98159-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-98160-0

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)