Abstract

Using a time-lagged design, we tested the main effects of Islamic Work Ethic (IWE) and perceived organizational justice on turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and job involvement. We also investigated the moderating influence of IWE in justice–outcomes relationship. Analyses using data collected from 182 employees revealed that IWE was positively related to satisfaction and involvement and negatively related to turnover intentions. Distributive fairness was negatively related to turnover intentions, whereas procedural justice was positively related to satisfaction. In addition, procedural justice was positively related to involvement and satisfaction for individuals high on IWE however it was negatively related to both outcomes for individuals low on IWE. For low IWE, procedural justice was positively related to turnover intentions, however it was negatively related to turnover intentions for high IWE. In contrast, distributive justice was negatively related to turnover intentions for low IWE and it was positively related to turnover intentions for high IWE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Organizational justice has its roots in Adams (1965) equity theory. Justice theory has remained an important area of inquiry in organizational sciences. Individuals expect fairness in procedures and distribution of rewards and when these expectations are violated they may experience negative emotions (Barclay et al. 2005). On these lines, many researchers have explored the relationship between organizational justice and various job outcomes (see Colquitt et al. 2001). Although this line of research is quite promising, there are some controversies regarding the impact of perceived fairness on job outcomes across cultures and across various dimensions of organizational justice (Colquitt et al. 2001; Shao et al. 2013) which need to be addressed. The generalizability of studies demonstrates that the influence of justice perceptions in Northern American and Asian settings still remains unclear (Li and Cropanzano 2009).

Meanwhile, much of the research on work ethics has been carried out in the West, with major focus on Protestant Work Ethic (PWE) advanced by Weber (1958). Research on Islamic Work Ethic or IWE has emerged as a separate domain of inquiry (Ali 1988, 1992; Yousef 2000a). Both PWE and IWE have a major focus on hard work, dedication, commitment, creativity, avoidance of wealth accumulation using unethical means, and cooperation at the workplace. However, contrary to PWE, IWE puts more emphasis on intentions than on results (Yousef 2000a). In contrast to PWE, the IWE has its deep roots in the Quran (the holy book of Muslims) and the Sunnah (sayings and practices) of the Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.W.Footnote 1) (Yousef 2000a). That being said, the work on IWE is still in its nascent stages.

Understanding business ethics from Islamic perspective becomes important for several reasons. First, Islam is the world’s second largest (after Christianity) monotheistic religion. Muslims constitute about 22.5 % of the world population today and the Muslim population globally has grown more than 1.5 times faster than the general population (Johnson and Grim 2013). Second, Muslim countries represent some of the major customers in the world and they have huge investments in Western countries (Saeed et al. 2001; Uddin 2003). Third, the need for a greater appreciation of workforce diversity in the face of globalization and heightened competition across the globe demands researchers and practitioners to understand the critical role of various religious and social factors that influence businesses (Eastman and Santoro 2009; Uddin 2003).

In the current study, we seek to continue broadening the literature on fairness perceptions and IWE by exploring their impact on important job outcomes such as job satisfaction, job involvement, and turnover intentions. We also examine the interplay between justice perceptions and IWE in predicting these outcomes. The controversies in the relationship between justice types and outcomes suggest the possibility of the presence of personal or contextual factors that may moderate these relationships (Colquitt et al. 2001, 2006). Thus, we feel that incorporating IWE into justice literature will yield new insights regarding the boundary conditions of justice perceptions and it will help explaining the conditions where fairness perceptions may or may not yield the desirable outcomes. Religion has always been a spiritual motivator for people to achieve particular objectives (Ali et al. 1995). IWE views work as a means to foster social relations and personal growth (Ali and Al-Owaihan 2008). IWE discourages laziness and encourages one’s search for legal source of income and dedication to work. Further, IWE considers engagement in economic activity as an obligation upon its adherents (Yousef 2000a). Therefore, it is likely that those individuals who adhere to IWE may be more satisfied and perform better than those who report low on IWE.

Moreover, being tested in a unique Eastern cultural setting, the current study will provide some insight into the dominant justice theory that has been mainly developed and tested in Western settings. Recently, organizational theorists have called upon future research to extend the organizational theories to Eastern settings to have more confidence about their generalizability (Tsui et al. 2007). Thus, current study fills this gap and provides an opportunity to test theories largely developed in West in non-Western settings.

Theory and Hypotheses

Organizational Justice and Job Outcomes

In organizational context, the term justice is used to refer to allocation of resources and rewards (Notz and Starke 1987). In any organization, the individuals can evaluate justice along a number of dimensions. Among the earlier works on organizational justice, the perceived fairness of decision outcomes was the main focus of research (Adams 1965). Later research demonstrated that individuals are not only concerned about the fairness in decision outcomes but also about the fairness of the procedures used to make those decisions (Bies and Moag 1986; Leventhal 1976; Leventhal et al. 1980; Thibaut and Walker 1975). In particular, numerous studies have explored the differential and combined effects of distributive and procedural justice on a wide array of organizationally important outcomes. Distributive justice refers to the fairness of outcome distributions or allocations (Adams 1965; Barsky and Kaplan 2007; Bauer et al. 2001; Colquitt et al. 2001) and procedural justice entails fairness of the procedures used to determine outcome distributions or allocations (Barsky and Kaplan 2007; Colquitt et al. 2001; Leventhal et al. 1980).

In organizations, individuals react emotionally to fairness of treatment in workplace exchanges and allocations which ultimately lead to perceptual and behavioral consequences (Barsky et al. 2011). Extant research has linked distributive and procedural justice to a variety of job outcomes. However, there has remained a controversy among studies that relate justice types to job outcomes. For example, Moorman et al. (1993) found a significant and positive relationship between procedural justice and job satisfaction. Alexander and Ruderman (1987) in their study of government employees found that both distributive and procedural justice are significantly related to job satisfaction. Later on, Aryee et al. (2002) also found positive associations of distributive and procedural with employees’ job satisfaction. In the same vein, Lam et al. (2002) found significant impact of distributive and procedural justice on job satisfaction.

However, other researchers found that only procedural justice but not distributive justice was related to job satisfaction (Lambert et al. 2007). Bakhshi et al. (2009) conducted a study on employees of medical college and found that distributive justice showed a significant relationship with job satisfaction whereas procedural justice was not significantly related to job satisfaction. According to McFarlin and Sweeney (1992), distributive justice was a stronger predictor of job satisfaction than procedural justice. In contrast, other studies found that procedural justice had a strong relationship with job satisfaction (e.g., Clay-Warner et al. 2005; Masterson et al. 2000; Mossholder et al. 1998; Wesolowski and Mossholder 1997).

In addition, previous research has examined the relationship between justice types and job involvement. Job involvement is “the degree to which a person is identified psychologically with his or her work or the importance of work in his or her total self-image” (Singh and Kumari 1988, p. 411). Ahmadi (2011) found a positive relationship of distributive and procedural justice with job involvement. With regard to an individual’s intentions to leave his or her organization, some studies found a significant relationship of both distributive and procedural justice types with turnover intentions (Alexander and Ruderman 1987; Aryee et al. 2002). In another study, Dailey and Kirk (1992) found that only procedural justice was significantly related to turnover intentions. Furthermore, Colquitt et al. (2001) in their meta-analysis found that distributive justice had a strong correlation with job satisfaction and withdrawal behaviors whereas procedural justice was strongly related to job satisfaction and moderately related to withdrawal behaviors.

There is also some evidence for the effects of justice types on job outcomes across cultures. For example, Fields et al. (2000) found that, for employees in Hong Kong and U.S., both distributive and procedural justice influenced evaluation of supervision, intention to stay, and job satisfaction. However, distributive justice had strong effects on job satisfaction and intent to stay in Hong Kong. Fields et al. (2000) attributed the differences between Hong Kong and U.S. employees to cultural influences such as power distance and collectivism. Hong Kong ranks higher on power distance and collectivism as compared to U.S. (Hofstede 1991). Pakistan also ranks higher on power distance and collectivism (Hofstede 1983). More recently, Shao et al. (2013) conducted a meta-analytic review on justice perceptions across cultures. Their review indicated the effects of justice perceptions on work outcomes to be strongest among nations associated with high individualism and low power distance. Similarly, Li and Cropanzano (2009) in their meta-analysis found that both procedural and distributive justice perceptions were related significantly to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, trust, and turnover intentions in East Asian culture. They also found that these justice perceptions were more strongly related to job outcomes in North America as compared to East Asia.

Pillai et al. (2001) found that procedural justice was an important predictor of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in U.S. sample whereas distributive justice was an important predictor of these outcomes in Indian sample. It can be due to the reason that Indian culture puts more emphasis on distributive justice which may account for reduced emphasis on procedures to correct injustice (Pillai et al. 2001). In a similar vein, justice perceptions were stronger among low power distance individuals than individuals who had high power distance (Lam et al. 2002).

Although the effect sizes of justice perceptions and outcomes in our study may be weaker as compared to North American samples. Together, the evidence suggests that both distributive and procedural justice should be related to work outcomes. When individuals perceive that the procedures used for distribution of rewards and the actual distribution of rewards are fair, they feel satisfied with their jobs and tend to reciprocate by demonstrating elevated levels of job involvement and reduced intentions to leave their organizations. We expect to replicate the findings that both distributive and procedural justice will be positively related to job satisfaction and job involvement and negatively related to turnover intentions in Pakistan.

Hypothesis 1a

Distributive justice will be positively related to job satisfaction and job involvement and negatively related to turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 1b

Procedural justice will be positively related to job satisfaction and job involvement and negatively related to turnover intentions.

IWE and Job Outcomes

Ethics are the moral principles that distinguish right from the wrong. Being an important element of business and day to day activities, awareness of ethical and moral dimensions of business practices has become an imperative subject area for academic world, businesses, governments, and the general public (Ahmed et al. 2003; Crane and Matten 2007; Sen 1993). Concept of ethics has its roots in Weber’s theory of PWE that has remained a major focus for business ethics research in the West (Yousef 2000a). In recent years, IWE (IWE), a concept introduced by Ali (1988) with a focus on Islamic ethical practices in the business, has become a separate domain of inquiry. IWE originates from teachings of Quran and Sunnah of Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.W.) (Ali and Al-Owaihan 2008; Rice 1999; Yousef 2000a). Both of these are the primary sources that offer broad principles and guidelines for conducting Islamic life and are presumed to be valid for all times and for all individuals who embrace Islam (Beekun and Badawi 2005). The literal meaning of the word “Islam” is peace that is achieved through complete and unconditional submission to Allah’s or God’s will in all spheres of life (Abuznaid 2006; Uddin 2003).

In Islam, for instance, “it is the ethic that dominates economics and not the other way around” (Rice 1999, p. 346) and every action is judged through the lens of Islamic ethics and values. Muslims, therefore, are obliged to follow the code, as described by the Shariah (Islamic Law and Jurisprudence). Thus, a Muslim is required to surrender completely to Allah’s will (Syed and Ali 2010). Islam is a religion that provides a comprehensive system, with its roots in ethics, which governs all spheres of life including the social and economic activities (Naqvi 1981; Rice 1999). It covers individual as well as collective lives of the followers in religion, social, economic, and political spheres (Beekun 1997). It is, therefore, expected that the religious beliefs of Muslims will be reflected in their laws, social interactions, and business practices including the work ethics (Syed and Ali 2010). Moreover, IWEs, having their roots in Islamic Law, are permanent and universal and therefore are not confined to one set of individuals, society, or a certain profession.

Moreover, in Islam, culture is regarded as part of the whole system of Islamic living and does not have a distinct identity outside the boundaries of Shariah (Islamic law and jurisprudence). Cultural norms and values in Islamic societies stem from Islamic principles and take shape according to the behaviors of Muslims, as guided by the Shariah rather than culture, as a distinct parameter, influencing the attitudes and behaviors of the followers (Ali and Al-Owaihan 2008).

Therefore, IWE is part of religious belief system of Muslims. In Islam, productive work is the part of religious duty and the relationship between two has been mentioned at several places in Quran (Abeng 1997). For example, Quran says “and he who does righteous deeds and he is a believer, he will neither have fear of injustice nor deprivation” (20:112) and “for those who were believers and they did righteous deeds, are the Gardens as accommodation for their deeds” (32:19). Furthermore, Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.W.) said that hard work absolves the sins of people and the best food which a person eats is that which he eats out of his work (Ali 1992; Ali and Gibbs 1998).

Islamic teachings emphasize loyalty, hard work, and human dignity (Ali 1992). In Islam hard work is considered necessary for the welfare of society (Ali 1992) and a laborer or a worker is considered as a friend of God. Islam promotes prosperity through the appropriate use of resources granted by God. Work is therefore considered as a source of independence and a way to attain a fulfilled life (Parboteeah et al. 2009). Quran says “for all people, there are ranks according to their deeds” (6:132) “and man has nothing except that for which he strives” (53:39). Thus, Islam encourages hard work and highly discourages laziness and waste of time by remaining idle or engaging oneself in unproductive activities (Abeng 1997; Yousef 2001). Consequently, IWE suggests that work is a virtue as well as necessity to maintain equilibrium in one’s personal and social life (Ali 1988).

In the perspective of IWE, life without work has no meaning and engagement in economic activities is an obligation. Thus, it emphasizes on cooperation at work and consultation as a source of happiness and success (Yousef 2000a). In IWE, work is considered as a source of satisfaction, accomplishment, and self-fulfillment (Nasr 1985). Previous research has found IWE to be positively associated with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. For example, Yousef (2001) conducted a study on Muslim employees in several organizations in United Arab Emirates (UAE) and found that IWE had a positive impact on employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

In another study, Yousef (2000b) examined the impact of IWE on organizational commitment and attitudes toward organizational change. Using a sample from UAE, the author found that IWE significantly and positively affected various dimensions of both attitudes toward organizational change and organizational commitment. IWE covering economic, moral, and social aspects provides faithfulness and strengthens commitment and continuity with one’s work. In this sense, work acts as a way of advancing social relations and personal growth (Ali and Al-Owaihan 2008).

In addition, IWE can be an important predictor of employee turnover intentions. Research suggests that employees who have orientation toward IWE are less likely to leave their organizations (Ahmad 2011). Therefore, we believe that employees with high IWE should be more satisfied, demonstrate elevated levels of job involvement, and are less likely to leave the organization. Consequently, we propose that

Hypothesis 2

IWE will be positively related to job satisfaction and job involvement and negatively related to turnover intentions.

The Moderating Role of IWE

Together, the controversies in the relationship between justice types and outcomes, as discussed previously, suggest the possibility of the presence of personal or contextual factors that may moderate these relationships (Colquitt et al. 2001, 2006). Since the IWE emphasizes justice and generosity at the workplace (Yousef 2000a) it may be an important moderator in the relationship between justice types and job outcomes. IWE is part of an individual’s belief system, therefore we argue that the individuals, who are high on IWE, will be able to buffer against the absence of organizational fairness. Particularly, situations where there is a lack of distributive and procedural fairness may be less harmful for individuals high on IWE, as these individuals may not bother too much about the absence of distributive and procedural fairness.

When an employee perceives unfairness in the procedures and distribution of rewards, these lowered fairness perceptions tend to reduce job satisfaction and increase one’s intentions to withdraw from job. However, individuals with high IWE should be less likely to respond negatively to these unfair treatments. According to IWE, work-related goals are considered as moral obligations that are to be achieved even in the absence of fair procedures and distributions of rewards. For example, Quran says “and he who does righteous deeds and he is a believer, he will neither have fear of injustice nor deprivation” (20:112). Therefore, we believe that individuals, who are high on IWE, may not bother when organizational justice is low. Bouma and colleagues state that the stress on activity and its relationship to the hereafter is understood to mean that Muslims have a moral obligation to work (Bouma 2003; Bouma et al. 2003).

Similarly, research on religiosity suggests that religion drives the integral belief system of an individual and it significantly influences the intrinsic and extrinsic work values of that individual (Parboteeah et al. 2009). Since, IWE is an essential component of the Muslim beliefs and value systems, employees with higher levels of IWE would exhibit higher levels of job satisfaction and job involvement and low turnover intentions even in the situations where procedural and distributive justice perceptions are low.

Hypothesis 3a

IWE will moderate the positive relationship of distributive justice with job satisfaction and job involvement such that the relationships will be stronger when IWE is high.

Hypothesis 3b

IWE will moderate the negative relationship between distributive justice and turnover intentions such that the relationship will be weaker when IWE is high.

Hypothesis 3c

IWE will moderate the positive relationship of procedural justice with job satisfaction and job involvement such that the relationships will be stronger when IWE is high.

Hypothesis 3d

IWE will moderate the negative relationship between procedural justice and turnover intentions such that the relationship will be weaker when IWE is high.

Methods

Sample and Data Collection Procedures

For current study, we collected data from medical doctors, non-doctor faculty members, and administrative and management staff (officer level) of a large private university which also manages large teaching hospitals in the capital city of Pakistan. The data was collected through self-administered questionnaires. A cover letter was attached with each questionnaire to explain the purpose of the study and to ensure confidentiality of data provided by the respondents. In time 1, respondents completed self-report version of questionnaire that contained items related to justice types and IWE. The survey responses for job satisfaction, job involvement, and turnover intentions were gathered in time 2 with 1 month time lag. Furthermore, each respondent also provided his or her demographic information such as age, gender, nature of job, work experience, education, and recent job status. No major events took place during the collection of data in these organizations.

Of the distributed 250 questionnaires, we received 182 complete surveys with a response rate of 73 %. Such high response rates are not uncommon in studies conducted in Asian contexts (e.g., Abbas et al. 2012; Raja et al. 2004). The demographic results revealed that the majority of respondents (69.8 %) were male. About 22 % respondents had ages up to 25 years, 71 % had ages between 26 to 50 years, and 7 % were above 50 years of age. The sample showed significant variations across occupational levels comprising of 40.1 % officers (all grades), 13.2 % managers (all grades), 38.5 % assistant professors, 3.8 % associate professors/full professors and 4.4 % deans and directors. About 11 % had experience above 20 years, 6 % had experience between 15 to 19 years, 11 % had experience between 10 to 14 years, 28 % had experience between 5 to 9 years, and 44 % had experience less than 5 years. The average tenure was 3.87 (SD = 1.33) years. About 51.7 % respondents had a post-graduate degree, 43.6 % were graduates and only 4.7 % were undergraduates. In order to avoid common method bias, we collected data on justice types and IWE in time 1 and collected data on job satisfaction, job involvement, and turnover intentions in time 2, i.e., 1 month later.

Measures

All constructs were measured using self-reports. All the responses were accessed using a 5-point Likert-type scale with anchors 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree.

Justice Types

(Measured in Time 1) We used 12-items scale to measure procedural justice and 11-items scale to measure distributive justice developed by Paré and Tremblay (2000). Examples of items for procedural justice include “The criteria used to grant promotions are clearly defined” and “Promotions are fundamentally determined by unfair politic games (reverse coded).” Sample items for distributive justice include “I estimate my salary as being fair internally” and “My supervisor has the tendency to give the same performance ratings to all of his employees (reverse).” Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities of procedural justice and distributive justice were 0.75 and 0.73, respectively.

IWE

(Measured in Time 1) IWE was measured by a 17-items questionnaire developed by Ali (1992). Examples of items include “One should carry out work to the best of one’s ability,” “Life has no meaning without work,” “Laziness is a vice,” and “Dedication to work is a virtue.” Alpha reliability was 0.81.

Job Outcomes

(Measured in Time 2) Overall job satisfaction was measured by a 5-items scale developed by Cammann et al. (1979) and Spector (1985). This measure includes items such as “I feel a sense of pride in doing my job” and “In general, I don’t like my job” (reverse). The reliability of this measure was 0.67. Turnover intentions were measured by a 3-items scale of Vigoda (2000) which included items such as “I often think about quitting this job” and “Next year I will probably look for a new job outside this organization.” The reliability of this measure was 0.78. A 9-items scale by White and Ruh (1973) was used to measure job involvement. The examples of items include “My job means a lot more to me than just money” and “I will stay overtime to finish a job, even if I’m not paid for it.” The reliability of this measure was 0.71.

Control Variables

We used gender as control variable because of its possible effects on job outcomes (Blomme et al. 2010).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, and the alpha reliabilities. Correlations of distributive justice with job satisfaction (r = 0.22, p < 0.01) and turnover intentions (r = −0.17, p < 0.05) were significant and in expected directions except for job involvement which was, although positive, but not significant (r = 0.10, n.s.). Correlations of procedural justice with job satisfaction (r = 0.29, p < 0.01) and job involvement (r = 0.20, p < 0.01) were also significant and in expected directions except for turnover intentions which was not significant (r = −0.11, n.s.). Correlations of IWE with turnover intentions (r = −0.21, p < 0.01), job satisfaction (r = 0.26, p < 0.01) and job involvement (r = 0.32, p < 0.01) were all significant and in expected directions.

Regression Analyses

Multiple linear regression analysis was used to test all main effect hypotheses. Regression results for main effects of distributive justice, procedural justice, and IWE on job outcomes are reported in Table 2. For main effects, gender was entered in the first step and all independent variables were entered in the second step. Results indicated that distributive justice significantly predicted turnover intentions (β = −0.18, p < 0.06) but not job satisfaction (β = 0.06, n.s.) and job involvement (β = −0.04, n.s.). These results support Hypothesis 1a for turnover intentions only. Similarly, Table 2 shows that procedural justice was positively related to job satisfaction (β = 0.19, p < 0.05), however, it did not significantly predict turnover intentions (β = 0.07, n.s.) and job involvement (β = 0.14, n.s.). These results support Hypothesis 1b for job satisfaction only. Table 2 further presents that IWE has a significant positive relationship with job satisfaction (β = 0.19, p < 0.05) and job involvement (β = 0.28, p < 0.001) and a significant negative relationship with turnover intentions (β = −0.19, p < 0.05). These results render support for Hypothesis 2.

Moderated regression analysis (Cohen et al. 2003) was used to test Hypotheses 3a through 3d. For this purpose, we centered the independent and moderating variables. Gender as control variable was entered in the first step. Independent and moderating variables were entered in the second step. In the third step, product terms of independent and moderator variables (distributive justice × IWE) and (procedural justice × IWE) were entered, which if significant confirmed moderation. Results in Table 2 show that the interaction term of distributive justice × IWE was significant for Turnover intentions (β = 0.17, p < 0.05) but not for job satisfaction (β = −0.13, n.s.) and job involvement (β = −0.10, n.s.). IWE did not moderate the relationship between distributive justice and job satisfaction and job involvement. Therefore Hypothesis 3a was not supported. Moreover, the interaction term of procedural justice × IWE was significant for turnover intentions (β = −0.19, p < 0.05), job satisfaction (β = 0.18, p < 0.05) and job involvement (β = 0.15, p < 0.05).

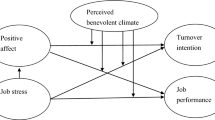

We plotted the significant interactions for high and low (mean ± SD) values of the moderator. Figure 1 shows that distributive justice-turnover intentions relationship was negative when IWE was low and this relationship was positive when IWE was high. Simple Slope test revealed that the negative slope for low levels of IWE was significant (β = −1.04, p = 0.05), however, the positive slope for high levels of IWE was not significant (β = 0.27, n.s.). These findings support Hypothesis 3b suggesting that individuals low on IWE are adversely affected when distributive justice was low whereas individuals high on IWE are not affected by the absence of distributive justice, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 2 shows that procedural justice-turnover intentions relationship was negative for high IWE, however, this relationship was positive for low IWE. Slope test further revealed that the negative slope for high levels of IWE was not significant (β = −0.56, n.s.) and the positive slope for low levels of IWE was significant (β = 1.12, p < 0.05). Thus, our results partially support Hypothesis 3d suggesting that individuals, who are high on IWE, may not leave the organization in the absence of procedural fairness. However, contrary to our expectations, individuals who are low on IWE are more likely to leave the organization when procedural justice is high than when it is low.

Figure 3 shows that the relationship between procedural justice and job satisfaction was positive when IWE was high; however, this relationship was negative when IWE was low. Slope test further revealed that the slope for high levels of IWE was significant (β = 0.61, p < 0.01) whereas the slope for low levels of IWE was not significant (β = −0.41, n.s.). These results support Hypothesis 3c for job satisfaction.

In Fig. 4, interaction plots show that procedural justice-job involvement relationship was positive when IWE was high; however, this relationship was negative when IWE was low. Slope test showed that the slope was significant for high levels of IWE (β = 0.41, p < 0.05), however, it was not significant for low levels of IWE (β = −0.32, n.s.). These results render support for Hypothesis 3c for job involvement.

Discussion

Despite several meta-analyses, the findings for the effects of procedural and distributive justice on a variety of job outcomes remain inconclusive. In fact, studies reveal cross cultural difference in responses to these two types of organizational justice. In an effort to provide some more evidence on the relationship between justice types and job outcomes, the current study examined the effects of distributive and procedural justice on job involvement, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. In addition, we investigated the impact of IWE on these outcomes. Moreover, in the wake of this inconsistent evidence for the relationships of justice types with job outcomes, we examined the moderating role of IWE in these relationships.

Our study reveals several interesting findings. Our results indicate that high perceived distributive justice can help the employees reduce turnover intentions whereas high procedural justice increases their job satisfaction. Our findings also indicate that high IWE among the employees can enhance their job satisfaction and job involvement and reduce turnover intentions.

As discussed in the theory section, previous research suggests that the effects of distributive and procedural fairness on a variety of job outcomes are inconsistent across cultures (Li and Cropanzano 2009; Shao et al. 2013). For example, several studies including meta-analyses suggest that procedural justice is more strongly related to job outcomes in Western samples whereas distributive justice is strongly related to outcomes in Eastern samples (Pillai et al. 2001). Other studies, using cultural lens, found that justice perceptions were stronger among nations associated with high individualism and low power distance (Lam et al. 2002; Shao et al. 2013). Pakistan is one of the countries that rank higher on power distance and collectivism (Hofstede 1983). However, we found some mixed evidence for the main effects of justice types on job outcomes. In our study, distributive justice was found to be a significant predictor of turnover intentions whereas procedural justice was found to be a significant predictor of job satisfaction. Both distributive and procedural justice did not predict job involvement. We believe, these findings suggest the presence of contextual factors which may possibly affect the relationship between justice types and job outcomes. In the current investigation, one contextual factor was IWE.

For the moderating role of IWE, we found some surprising evidence. Contrary to our expectations, distributive justice was negatively related to turnover intentions for individuals low on IWE. In other words, individuals low on IWE were adversely affected by perceived distributive unfairness whereas individuals high on IWE were not affected by the absence of distributive fairness, as shown in Fig. 1.

We also found that individuals high on IWE were least likely to leave their organizations when procedural justice was high. However, those low on IWE were more likely to leave their organizations when procedural justice was high. These findings indicate that individuals low on IWE may leave their organizations in face of high procedural justice. Possibly, low IWE individual may be more hedonistic with little interest in work and performance and more interested in gaining rewards through political or some other means without having to work for them. Therefore, such individuals may feel uncomfortable in environments where procedures for distribution of rewards are fair and strictly followed restricting their ability to gain rewards through other means. Maybe, because low IWE individuals do not like to work hard and they prefer laziness at workplace and hence consider fairness in the rules and procedures to be harmful for their survival leading to their heightened intentions to quit. On the contrary, individuals who possess high IWE tend to stay with their organizations when organizational procedures are fair.

Moreover, we found that individuals high on IWE were more satisfied with their jobs in face of high procedural justice, however, low IWE individuals tended not to be satisfied when procedural justice was high. In a similar vein, for individuals high on IWE, high procedural justice tended to enhance the levels of job involvement, however, for those low on IWE, high procedural justice tended to decrease job involvement. In other words, when individuals high on IWE feel that organizational processes are fair they are more satisfied with their jobs and demonstrate high levels of job involvement. Individuals high on IWE tend to be more concerned about procedural justice in their organization. In contrast, individuals who are low on IWE may feel procedural justice to be harmful for their survival hence reducing their job satisfaction and job involvement. Together, these findings suggest that IWE emphasizes on hard work, dedication, commitment, cooperation, generosity, and fairness in workplace (Yousef 2001).

We also compared the zero-order correlations of our study (Table 1) against the meta-analytic uncorrected correlations for East Asian samples reported by Li and Cropanzano (2009). With respect to distributive justice and turnover intentions, our obtained association (r = −0.17) was almost identical to that found for East Asian samples in Li and Cropanzano’s meta-analysis (r = −0.22, 95 % CI −0.32 to −0.11). However, for job satisfaction, the correlation observed in our study (r = 0.22) was almost half the size compared to that reported in Li and Cropanzano’s study (r = 0.40, 95 % CI 0.33–0.47).

With regard to procedural justice and job satisfaction and turnover intentions, our obtained associations (r = −0.11 for turnover intentions and r = 0.29 for job satisfaction) were close to those found for East Asian samples in Li and Cropanzano’s study (r = −0.18, 95 % CI −0.28 to −0.08 for turnover intentions and r = 0.36, 95 % CI 0.29–0.43 for job satisfaction) as their confidence intervals included the correlations observed in our study. Since Li and Cropanzano’s meta-analysis did not include job involvement, we could not compare the correlations. In their meta-analysis, Li and Cropanzano (2009) reported that the effect sizes tended to be larger in North America than in East Asia. Together these findings suggest that, in general, justice perceptions tend to be more strongly related to outcome variables in North American samples than in Asian samples.

Managerial Implications

The results of this study have several implications for managers of multinational corporations considering doing business in Islamic markets. First, the findings provide some insights into the critical role of IWE in increasing job satisfaction and job involvement and reducing turnover intentions. Managers can play their roles as moral champions and efforts can be directed toward support of IWE at the workplace. Ethics is considered as one of the key components of any organization’s core values (Carroll and Buchholtz 2006; Rice 1999; Schwartz and Carroll 2008). However, it may not be very useful to implement the same code of ethics around the world (Rice 1999). Managers of the multinational firms working in Islamic countries can develop and implement Islamic codes of ethics to enhance employees’ dedication and involvement in their jobs.

Several studies show that ethics can be taught to managers (Jones 2009; Lau 2010; Waples et al. 2009). Islam is considered as the only religion that provides a practical-life program that gives directions to every sphere of life (Rice 1999). Through proper trainings and lectures, levels of IWE can be enhanced among employees. Since Muslims constitute 22.5 % of the world population (Johnson and Grim 2013) and represent some of the major customers of the world (Saeed et al. 2001; Uddin 2003) such training initiatives may be more important for MNCs working in Islamic countries.

Moreover, managers should be wary about the harmful effects of perceived distributive and procedural unfairness among employees. Managers should identify and address the issues that trigger perceived unfairness within the work environment.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study is not without limitations. Although we measured independent and dependent variables with 1 month time lag to avoid method bias issues, causality may not be inferred. Another limitation is the slightly lower reliability of job satisfaction (α = 0.67). Although many studies have investigated the impact of IWE on a variety of job outcomes, more attention may be required to examine the role of IWE in effectiveness of organizational members. Future research should examine the impact of IWE on other important job outcomes such as work engagement, emotional well-being, and employee citizenship behaviors. Having its roots in one’s belief system, IWE has the capacity to protect one’s self from organizational stressors. Future studies may examine the moderating role of IWE in the relationship between job-related stressors and work outcomes.

Notes

S.A.W.W. is an abbreviation for an Arabic phrase that means “Peace Be upon Him and His Family,” an honorific formula that Muslims use when the name of Prophet Muhammad is mentioned. This abbreviation will be used in the rest of this article.

References

Abbas, M., Raja, U., Darr, W., & Bouckenooghe, D. (2012). Combined effects of perceived politics and psychological capital on job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and performance. Journal of Management,. doi:10.1177/0149206312455243.

Abeng, T. (1997). Business ethics in Islamic context: Perspectives of a Muslim business leader. Business Ethics Quarterly, 7(3), 47–54.

Abuznaid, S. (2006). Islam and management: What can be learned? Thunderbird International Business Review, 48(1), 125–139.

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267–299). New York: Academic Press.

Ahmad, M. S. (2011). Work ethics: An Islamic prospective. International Journal of Human Sciences, 8(1), 850–859.

Ahmadi, F. (2011). Job involvement in Iranian Custom Affairs Organization: The role of organizational justice and job characteristics. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 1(2), 40–45.

Ahmed, M. M., Chung, K. Y., & Eichenseher, J. W. (2003). Business students’ perception of ethics and moral judgment: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Business Ethics, 43, 89–102.

Alexander, S., & Ruderman, M. (1987). The role of procedural and distributive justice in organizational behavior. Social Justice Research, 1(2), 177–198.

Ali, A. (1988). Scaling an Islamic work ethic. The Journal of Social Psychology, 128(5), 575–583.

Ali, A. (1992). The Islamic work ethic in Arabia. The Journal of Psychology, 126(5), 507–519.

Ali, J. A., & Al-Owaihan, A. (2008). Islamic work ethic: A critical review. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 15(1), 5–19.

Ali, A. J., & Gibbs, M. (1998). Foundation of business ethics in contemporary religious thought: The Ten Commandment perspective. International Journal of Social Economics, 25(10), 1552–1564.

Ali, A. J., Falcone, T., & Azim, A. A. (1995). Work ethic in the USA and Canada. Journal of Management Development, 14(6), 26–34.

Aryee, S., Budhwar, P. S., & Chen, Z. X. (2002). Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 267–285.

Bakhshi, A., Kumar, K., & Rani, E. (2009). Organizational justice perceptions as predictor of job satisfaction and organization commitment. Journal of Business and Management, 4(9), 145–154.

Barclay, L. J., Skarlicki, D. P., & Pugh, S. D. (2005). Exploring the role of emotions in injustice perceptions and retaliation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 629–643.

Barsky, A., & Kaplan, S. A. (2007). If you feel bad, it’s unfair: A quantitative synthesis of affect and organizational justice perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 286–295.

Barsky, A., Kaplan, S. A., & Beal, D. J. (2011). Just feelings? The role of affect in the formation of organizational fairness judgments. Journal of Management, 37(1), 248–279.

Bauer, T. N., Truxillo, D. M., Sanchez, R. J., Craig, J. M., Ferrara, P., & Campion, M. A. (2001). Applicant reactions to selection: Development of the selection procedural justice scale. Personnel Psychology, 54, 387–419.

Beekun, R. I. (1997). Islamic business ethics. IslamKotob.

Beekun, R. I., & Badawi, J. A. (2005). Balancing ethical responsibility among multiple organizational stakeholders: The Islamic perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 60(2), 131–145.

Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. S. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. In R. J. Lewicki, B. H. Sheppard, & M. Bazerman (Eds.), Research on negotiation in organizations (Vol. 1, pp. 43–55). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Blomme, R. J., Van Rheede, A., & Tromp, D. M. (2010). The use of the psychological contract to explain turnover intentions in the hospitality industry: A research study on the impact of gender on the turnover intentions of highly educated employees. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(1), 144–162.

Bouma, G. D. (2003). Transnational factors affecting the study of religion and spirituality. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion, 14, 211–228.

Bouma, G., Haidar, A., Nyland, C., & Smith, W. (2003). Work, religious diversity and Islam. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 41(1), 51–61.

Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan organizational assessment questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Carroll, A., & Buchholtz, A. (2006). Business and society: Ethics and stakeholder management. Mason: Thompson Learning.

Clay-Warner, J., Reynolds, J., & Roman, P. (2005). Organizational justice and job satisfaction: A test of three competing models. Social Justice Research, 18(4), 391–409.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S., & Aiken, L. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425–445.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Judge, T. A., & Shaw, J. C. (2006). Justice and personality: Deriving theoretically based moderators of justice effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100, 110–127.

Crane, A., & Matten, d. (2007). Business ethics: Managing corporate citizenship and sustainability in the age of globalization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dailey, R. C., & Kirk, D. J. (1992). Distributive and procedural justice as antecedents of job dissatisfaction and intent to turnover. Human Relations, 45, 305–317.

Eastman, W., & Santoro, M. (2009). The importance of value diversity in corporate life. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13(4), 433–452.

Fields, D., Pang, M., & Chiu, C. (2000). Distributive and procedural justice as predictors of employee outcomes in Hong Kong. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(5), 547–562.

Hofstede, G. (1983). The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 14(2), 75–89.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. London: McGraw-Hill.

Johnson, T. M., & Grim, B. J. (2013). Global religious populations 1910–2010. The world’s religions in figures: An introduction to international religious demography (pp. 9–78). Chichester: Wiley.

Jones, D. A. (2009). A novel approach to business ethics training: Improving moral reasoning in just a few weeks. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(2), 367–379.

Lam, S., Schaubroeck, J., & Aryee, S. (2002). Relationship between organizational justice and employee work outcomes: A cross national study. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 23, 1–18.

Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., & Griffin, M. L. (2007). Impact of distributive and procedural justice on correctional staff job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Journal of Criminal Justice, 35(6), 644–656.

Lau, C. L. (2010). A step forward: Ethics education matters! Journal of Business Ethics, 92(4), 565–584.

Leventhal, G. S. (1976). The distribution of rewards and resources in groups and organizations. In L. Berkowitz & W. Walster (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 9, pp. 91–131). New York: Academic Press.

Leventhal, G. S., Karuza, J., & Fry, W. R. (1980). Beyond fairness: A theory of allocation preferences. In G. Mikula (Ed.), Justice and social interaction (pp. 167–218). New York: Springer.

Li, A., & Cropanzano, R. (2009). Do East Asians respond more/less strongly to organizational justice than North Americans? A meta-analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 46(5), 787–805.

Masterson, S. S., Lewis, K., Goldman, B. M., & Taylor, M. S. (2000). Integrating justice and social exchange: The differing effects of fair procedures and treatment on work relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 738–748.

McFarlin, D. B., & Sweeney, P. D. (1992). Distributive and procedural justice as predictors of satisfaction with personal and organizational outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 626–637.

Moorman, R. H., Niehoff, B. P., & Organ, D. W. (1993). Treating employees fairly and organizational citizenship behaviors: Sorting the effects of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and procedural justice. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 6, 209–225.

Mossholder, K. W., Bennett, N., & Martin, C. L. (1998). A multilevel analysis of procedural justice context. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 131–141.

Naqvi, S. N. H. (1981). Ethics and economics: An Islamic synthesis (Vol. 2). London: Islamic Foundation.

Nasr, S. H. (1985). Islamic work ethic in comparative work ethics. Occasional papers of the Council of Scholars. Washington, DC: Library of Congress.

Notz, W. W., & Starke, F. A. (1987). Arbitration and distributive justice: Equity or equality? Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(3), 359–365.

Parboteeah, K. P., Paik, Y., & Cullen, J. B. (2009). Religious groups and work values: A focus on Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism and Islam. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 9(1), 51–67.

Paré, G., & Tremblay, M. (2000). The measurement and antecedents of turnover intentions among IT professionals. Working paper no. 2000s-33, CIRANO Working Papers.

Pillai, R., Williams, E. S., & Tan, J. J. (2001). Are the scales tipped in favor of procedural or distributive justice? An investigation the U.S., India, Germany and Hong Kong (China). International Journal of Conflict Management, 12(4), 312–332.

Quran. (1981). Arabic Text and English Translation. Elmhurst: Islamic Seminary.

Raja, U., Johns, G., & Ntalianis, F. (2004). The impact of personality on psychological contracts. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 350–367.

Rice, G. (1999). Islamic ethics and the implications for business. Journal of Business Ethics, 18, 345–358.

Saeed, M., Ahmed, Z. U., & Mukhtar, S. (2001). International marketing ethics from an Islamic perspective: A value-maximization approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 32, 127–142.

Schwartz, M., & Carroll, A. (2008). Integrating and unifying competing frameworks. The search for a common core in the business and society field. Business and Society, 47(2), 148–186.

Sen, A. (1993). Does business ethics make economic sense? In P. M. Minus (Ed.), The ethics of business in a global economy (pp. 53–66). Dordrecht: Springer.

Shao, R., Rupp, D. E., Skarlicki, D. P., & Jones, K. S. (2013). Employee justice across cultures: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 39, 263–301.

Singh, A. P., & Kumari, P. (1988). A study of individual need strength, motivation and job involvement in relation to job satisfaction, productivity and absenteeism. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 23(4), 409–428.

Spector, P. E. (1985). Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: Development of the job satisfaction survey. American Journal of Community Psychology, 13(6), 693–713.

Syed, J., & Ali, A. J. (2010). Principles of employment relations in Islam: A normative view. Employee Relations, 32(5), 454–469.

Thibaut, J., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Tsui, A. S., Nifadkar, S. S., & Ou, A. Y. (2007). Cross national, cross-cultural organization behavior research: Advance, gaps and recommendations. Journal of Management, 33, 426–478.

Uddin, S. J. (2003). Understanding the framework of business in Islam in an era of globalization: A review. Business Ethics: A European Review, 12(1), 23–32.

Vigoda, E. (2000). Organizational politics, job attitudes, and work outcomes: Exploration and implications for the public sector. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 57, 326–347.

Waples, E. P., Antes, A. L., Murphy, S. T., Connelly, S., & Mumford, M. D. (2009). A meta-analytic investigation of business ethics instruction. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(1), 133–151.

Weber, M. (1958). The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. New York: Scribner.

Wesolowski, M. A., & Mossholder, K. W. (1997). Relational demography in supervisor subordinate dyads: Impact on subordinate job satisfaction, burnout, and perceived procedural justice. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 351–362.

White, J. K., & Ruh, R. (1973). Effects of personal values on the relationship between participation and job attitudes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 8(4), 506–514.

Yousef, D. A. (2000a). Organizational commitment as a mediator of the relationship between Islamic work ethic and attitudes toward organizational change. Human Relations, 5, 513–537.

Yousef, D. A. (2000b). The Islamic work ethic as a mediator of the relationship between of control, role conflict and role ambiguity—A study in an Islamic country setting. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15, 283–298.

Yousef, D. A. (2001). Islamic work ethic—A moderator between organizational commitment and job satisfaction in a cross-cultural context. Personnel Review, 30, 152–164.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, K., Abbas, M., Gul, A. et al. Organizational Justice and Job Outcomes: Moderating Role of Islamic Work Ethic. J Bus Ethics 126, 235–246 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1937-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1937-2