Abstract

Given that quality early school experiences are predictive of later school success, fostering efficacious early education and kindergarten adjustment is an educational priority. Yet pre-COVID-19 research demonstrates that children who are at risk for academic difficulties experience barriers in school that require additional support during their early education. The COVID-19 global crisis has erected additional, unpredictable barriers that may be detrimental to early school experiences and, in many cases, has resulted in the elimination of early schooling opportunities altogether. While inimical to most children, eliminating early education opportunities for students with multiple risk factors (e.g., geographic isolation, developmental delays, and low socioeconomic status) sets conditions for an even higher risk of academic failure. This scoping review synthesizes current research on teacher, parent, and child experiences during pandemic-related school closures and recommendations for school adaptations and family support around early education and transition to kindergarten in the shadow of COVID-19. A scoping review of the literature was conducted, drawing upon four databases (ERIC, MEDLINE, APA PsycNet, and Science Direct). Searches included quantitative and qualitative studies published from January 2020 until the end of July 2021, examining inquiry into early education experiences and kindergarten transition during the COVID-19 pandemic for young children at-risk for academic difficulties. A total of 13 articles were included in the review. Results inform school transition, early childhood education practice, and means to support families with young children at-risk for academic difficulties as the pandemic continues and potential future crises arise.

This research was funded, in part, by a grant from the National Institute of Disability Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research (90DPHF0003) awarded to the second author.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted all aspects of life and has been especially disruptive to education and supports for young children (Barnett et al., 2020), including those with or at-risk for disabilities (Neece et al., 2020). In the United States most early childhood education (ECE) programs closed in spring 2020 as children and families sheltered in place. Children with early childhood special education (ECSE) support needs saw a significant decline in services. For example, in a large national survey, parents reported that only 37% of children receiving early childhood special education received full support, with the remaining 63% receiving partial support or no support at all after their preschool classrooms closed (Barnett et al., 2020). Loss of ECE and ECSE supports was especially devastating to low-income or racially, ethnically, or geographically minoritized families already experiencing heightened stress, stigma, and disadvantage (Neece et al., 2020; Soltero-Gonzalez & Gillanders, 2021).

Although the pandemic has had widespread and global impacts, the chaotic changes to early education and the impact on children’s school readiness will be felt for years to come. In this chapter, we present findings from a scoping review of global studies documenting the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on young children, families, and educators. A scoping review of the literature was chosen to identify available evidence within the preliminary research on COVID-19 and early education (Munn et al., 2018). The purpose of this review is to examine the emerging evidence that is available and use it to inform future research including the questions to pose in systematic reviews. We place these findings within the context of early learning, school readiness, and kindergarten transition.

Method

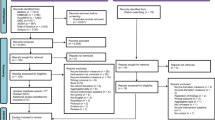

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using APA PsycNet, Science Direct, ERIC, and Medline to identify empirical studies published from January 2020 to July 2021. Studies investigating the effects of school closures and remote education due to COVID-19 on early childhood education that included experiences for families, young children, and their teachers were reviewed. The following inclusionary criteria were used to identify articles for the present review: (1) peer-reviewed journal article, (2) published in English between 2020 and present (July 2021), (3) quantitative and qualitative studies with methods and results related to early childhood education and school experiences, (4) focus on young children (2–8 years), and (5) children at-risk for academic challenges based on disability or delay, geographic isolation, or socioeconomic disadvantage. Articles that included remote therapy or educational experiences unrelated to early school experiences (i.e., preschool or kindergarten) were excluded. Study samples that included age groups beyond preschool and early education were included if the data reported could be parsed based on age category. As shown in Fig. 25.1, the initial search yielded 1118 studies, with 18 excluded for duplicates or non-peer-reviewed. Next, 1100 manuscripts were screened by title and abstract review to determine inclusion resulting in the exclusion of 1079. The remaining 21 manuscripts were reviewed in-depth to determine eligibility for the present review resulting in 13 peer-reviewed journal articles included in the review. Reasons for exclusion in this final stage of the review included child participants’ age range beyond early childhood without specific data for young children, no connection between family and return to school, or reports, summary articles, or opinion papers not based on empirical research. See Fig. 25.1 for an overview of the search strategy.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram

Note. *Manuscripts excluded after full review for the following reasons: Reason 1: age group beyond early childhood (EC) without specific data for EC age-group; Reason 2: No connection between family and return to school; Reason 3: Report or summary article (Page et al., 2021)

Results

Thirteen studies representing 14 different countries met the criteria (see Table 25.1). Although it is beyond the scope of this review to include statistical analysis, the study features and main findings on ECE and ECSE experiences and recommendations by authors are reviewed below. In particular, the following study characteristics are summarized: (1) study purpose, (2) participants: sample size, description, and country, (3) design and approach, (4) key outcomes, and (5) future recommendations.

Purpose of Included Studies

The purpose of all included studies was to provide a perspective of parents, teachers, or young children on their educational experiences in ECE or ECSE due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Three studies focused on teacher experiences in the transition from in-person teaching to virtual instruction (Atiles et al., 2021; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021; Steed & Leech, 2021). The study from Steed and Leech (2021) was the only study to focus on teachers in both ECE and ECSE programs specifically. Three studies solely focused on the impact of COVID-19 school closures on the parents of young children. Dong et al. (2020) explored Chinese parents’ beliefs and attitudes toward virtual education for their young children. Kim et al. (2021) looked to identify Ethiopian parents’ ability to facilitate learning at home for their young children. Soltero-Gonzales and Gillanders (2021) interviewed Latinx parents from low-income households in the United States to understand their experiences during this educational shift. Two studies (Otero-Mayer et al., 2021; Timmons et al., 2021) included perspectives of both teachers and parents in their study purpose. The goals of the remaining five studies were to have parents report their child’s experience with virtual learning due to school closures. While Barnett et al. (2021) focused only on parents’ reflections of child experiences, other studies combined perspectives: (a) parent and child by parent report (Eagan et al., 2021; Wendel et al., 2020), (b) parent, child by parent report, and teacher (Yildirim, 2021), and (c) child by parent report, teacher, child by child report, and assessment measures (Quenzer-Alfred et al., 2021).

Participants

All included studies focused on school and learning experiences of participants: early childhood teachers, parents, and young children in ECE or ECSE during the COVID-19 pandemic. The 13 articles included distinct study samples. The studies included a combined sample of 2733 teachers, 6777 parents, and 55 children. Sample sizes varied across the studies. More than half of the studies (n = 8; 61%) used surveys and reported on large sample sizes (median = 1114; range 184–3275). Five studies used interviews with smaller sample sizes (median = 30; range 13–55). Only one study used quantitative analysis of pre- and post-testing to determine child scores on a skill assessment, including 49 child participants in their analysis (Quenzer-Alfred et al., 2021).

All child participants were described as at-risk for poor academic performance and experiencing developmental delays due to change in educational opportunities. The majority of the children did not have a specified diagnosis, except for Wendel et al. (2020), in which children had a diagnosis of ADHD. Barnett et al. (2021) described participants as having an individualized education plan (IEP), thus qualifying under special education in their school settings (Barnett et al., 2021).

All but one study (Timmons et al., 2021) included demographic information on participants, such as community type (rural and urban), sex, and race/ethnicity. Of the 12 that reported demographic information, most studies included some information on participant ethnicity; however, the ethnicity was more often unspecified and reported as the country of residency rather than reported specifically by the participant. For example, Atiles et al. (2021) listed the number of participants from Latin American countries (i.e., Brazil, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, or Puerto Rico) without specifics of participant ethnicity. Dong et al. (2020) reported participants were from China, with no other description. Egan et al. (2021) described their participants as being from Ireland and the United Kingdom without further description. Because the studies took place in a wide range of countries, it is assumed that a diverse participant group is represented. Of the eight studies that reported adult participant sex, majority of the teachers and parents that participated identified as female (range = 84–100%).

Three studies described parent participants as experiencing economic barriers. Specifically, the sample in Atiles et al. (2021) included families with limited economic resources in various Latin American countries. Soltero-Gonzales and Gillanders (2021) recruited a sample of low-income Lantinx families in the United States. Kim et al. (2021) surveyed families in Ethiopia and described participants as living in poverty with minimal learning resources, no electricity, and inability to provide technology for learning opportunities. An exception to specific economic description was the study by Quenzer-Alfred et al. (2021). They stated the schools chosen as recruitment sites were in economically diverse urban areas to include families in poverty. However, the study’s description of economic barriers was not further defined.

Study Design and Instruments

Eight studies used a survey to gather the experiences of participants (Barnett et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2020; Egan et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021; Otero-Mayer et al., 2021; Steed & Leech, 2021; Wendel et al., 2020). Six of the eight survey studies used an online survey format (e.g., Qualtrics). Kim et al. (2021) conducted a phone survey as some participants would not have access to an online survey. Otero-Mayer et al. (2021) emailed a questionnaire to participants to complete, which was then returned via email. Most studies reported on cross-sectional data only, with participants responding to a survey at one point in time. In contrast, Wendel et al. (2020) used an online survey format and surveyed participants at three different time points.

The remaining five studies included in this review used interviews to collect participant data (Atiles et al., 2021; Quenzer-Alfred et al., 2021; Soltero-Gonzalez & Gillanders, 2021; Timmons et al., 2021; Yildirim, 2021). Two of these five interview studies included additional methods of data collection. Yildirim (2021) used video analysis of activities conducted with the child to support the interview data. Quenzer-Alfred et al. (2021) used qualitative analysis of pre- and post-assessments of child performance. Children were interviewed in small groups in addition to interviews of the parents and professionals individually.

Study Outcomes

All 13 studies reported evidence that participants did not find virtual education to be developmentally appropriate for young children (Atiles et al., 2021; Barnett et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2020; Egan et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021; Otero-Mayer et al., 2021; Quenzer-Alfred et al., 2021; Soltero-Gonzalez & Gillanders, 2021; Timmons et al., 2021; Steed & Leech, 2021; Wendel et al., 2020; Yildirim et al., 2021). Specifically, studies reported virtual learning as a detriment to social-emotional development (Egan et al., 2021; Timmons et al., 2021), while others described it as harmful to overall development, especially for children experiencing socioeconomic difficulties (Kim et al., 2021; Quenzer-Alfred et al., 2021; Wendel et al., 2020; Yildirim et al., 2021). Barnett et al. (2021) reported a decrease in ECSE services, for example, in type and frequency of services during school closures and a decrease in overall preschool enrollment due to virtual instruction.

O’Keefe and McNally (2021) described teachers’ attempts to facilitate parent–child interactions by encouraging play to address learning at home. Teachers emphasized the role of play across curriculum activities and expressed frustration and concerns regarding virtual play facilitation as well as play implementation during a return to school given COVID restrictions, such as social distancing and no shared materials. Additionally, Steed and Leach (2021) reported teachers’ struggle to accurately assess and evaluate the progress of young children due to limited teaching opportunities of basic concepts. Yildirim (2021) linked this deficit in teaching and assessment to schools’ lack of preparation to teach virtually. Participants believed low expectations on the part of the school system are partly responsible for the minimal developmental gain and limited academic growth in young children during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Seven studies reported on outcomes of limited training and preparation of teachers and parents to facilitate effective virtual education (Atiles et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021; Otero-Mayer et al., 2021; Soltero-Gonzalez & Gillanders, 2021; Steed & Leech, 2021; Timmons et al., 2021). Reported barriers preventing effective virtual learning included limited learning resources and materials in the homes (e.g., toys, books; Kim et al., 2021), lack of technology available to families (Kim et al., 2021; Otero-Mayer et al., 2021; Steed & Leech, 2021), minimal knowledge and time on the part of parents to facilitate activities (Dong et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021; Otero-Myer et al., 2021; Timmons et al., 2021). Steed and Leech (2021) found some teachers were also unprepared to teach virtually despite receiving training to do so, including difficulty in collaboration among professionals to facilitate learning. Both Steed and Leech (2021) and Timmons et al. (2021) reported limited guidance from administration to teachers on how to provide asynchronous and synchronous education to young children.

Eight studies demonstrated participants’ concern for the mental health and well-being of families (Atiles et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2020; Egan et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021; Soltero-Gonzalez & Gillanders, 2021; Steed & Leech, 2021; Timmons et al., 2021). For example, increased parent stress due to parents’ limited time and skills to teach their children was reported (Dong et al., 2020; Soltero-Gonzalez & Gillanders, 2021). In addition to heightened adult stress, increased rates of child discipline, more child stress, and anxiety were outcomes reported by various participants (Kim et al., 2021; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021). Eagan et al. (2021) reported on child responses suggesting that children missed their friends and playtime and generally missed being in school or childcare settings. Overall, Eagan et al. (2021) concluded children were worried and bored during the pandemic-related school closures. Although the pandemic was reported to have deleterious effects on families, findings from Eagan et al. (2021) suggest that more competent and resilient families had better mental health and well-being than less competent and resilient families. Finally, two studies reported that teachers also felt overwhelmed and had difficulty handling their own family life while supporting the families with whom they work (Steed & Leech, 2021; Timmons et al., 2021).

Future Recommendations

All included studies made recommendations for educational practices for young children, families, and teachers in post-COVID-19 circumstances and anticipation of future school closures. Five categories surfaced as dominant recommendation themes across studies. Recommendation themes are: (1) increasing teacher preparation, (2) implementing developmentally appropriate practices (DAP) in face-to-face and virtual early education, (3) addressing unmet needs of children, (4) supporting the need of families, and (5) instituting system-wide changes.

Increasing Teacher Preparation

Seven studies recommended preparing teachers to teach young children in virtual education platforms (Atiles et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2020; Otero-Mayer et al., 2021; Soltero-Gozalez & Gillanders, 2021; Steed & Leech, 2021; Timmons et al., 2021; Yildirim, 2021). Specific recommendations across the studies included having teachers receive technological training and preparation to use technology to teach young children and reach families (Atiles et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2020; Steed & Leech, 2021; Timmons et al., 2021; Yildirim, 2021). For example, Yildirim (2021) suggested guidebooks for teachers and parents with instructions for distance education paired with virtual adult learning opportunities and courses for continuing education credit. Otero-Mayer et al. (2021) argued professional training will increase teachers’ ability to provide individualized education during virtual instruction. Increasing teachers’ focus on families as a whole unit was also recommended, including training teachers to promote parent self-esteem and positive familial mental health (Atiles et al., 2021). Soltero-Gozalez and Gillanders (2021) recommended that teacher training focus on sociocultural practices for the families they work with (e.g., how parents play and teach their child in the home) and recommended adding these components into their teaching of young children upon returning to the classroom.

Implementing DAP in Virtual and Post-pandemic, Face-to-Face Early Education

Five studies identified inadequacies of virtual instruction for young children, recommending future practice changes (Atiles et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2020; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021; Timmons et al., 2021; Yildirim, 2021). Atiles et al. (2021) and Dong et al. (2020) both suggested that DAP standards be considered in curriculum planning. More specifically, ensuring individual needs and interests of the child are included in this planning as well (Atiles et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2020). O’Keefe and McNally (2021) recommended further research on the importance of play for young children with special needs in the aftermath of the pandemic and ECE. Additionally, Timmons et al. (2021) suggested that educators use both asynchronous and synchronous learning to encourage social development through curriculum adaptations and lesson planning. To expand this suggestion, Timmons et al. (2021) recommended informing families of learning expectations and lesson goals, making materials and resources available, and providing the option for individualized instruction as needed. Yildirim (2021) highlighted activities taught virtually should be short and appropriate for preschool-aged children.

Addressing Unmet Needs of Children

Seven studies recommended changes in practice to address the unmet need of young children during and post-virtual learning (Barnett et al., 2021; Eagan et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021; Quenzer-Alfred et al., 2021; Timmons et al., 2021; Wendel et al., 2020). Specifically, Barret et al. (2021) suggested that professionals recognize children’s limited experience with school routines and their lack of opportunity for adjustment to classroom expectations, ultimately considering that missed early experiences will impact their transition to kindergarten. Similarly, Egan et al. (2021) presented the importance of the teacher in support for young children in overcoming the negative impacts of COVID-19 on socioemotional development. Egan et al. (2021) suggested that teachers prioritize mental health and social-emotional development to establish resiliency and coping skills for young children. Along these lines, Kim et al. (2021) emphasized the importance of tracking mental health (e.g., psychosocial development), encouraging educational professionals to provide necessary support while considering unique disparities among families.

Various studies emphasized the importance of measurement and assessment (Barret et al., 2021, Kim et al., 2021; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021; Quenzer-Alfred et al., 2021; Timmons et al., 2021; Wendel et al., 2020). Kim et al. (2021) pointed to the importance of measures to determine the individual effect of school closures based on family circumstances (e.g., sense of community, violence in the home, job loss, and malnutrition) and the relationship of these factors with limited early learning opportunities. Other studies echoed the importance of monitoring progress in various developmental domains (e.g., social, emotional, physical, and academic) due to the impact of COVID-19 considering limited exposure to peers, minimal social opportunity, and decreased physical activity during quarantine (Barret et al., 2021; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021; Quenzer-Alfred et al., 2021; Wendel et al., 2020). Recommendations included partnering with parents upon re-opening to assess, measure, and monitor children’s progress, as well as focusing on parental engagement with ECE (Barret et al., 2021). Further, these formal and informal assessments should use curriculum adaptations to meet children’s individual needs accurately (Timmons et al., 2021).

Supporting Needs of Families

Five studies gave specific recommendations in support of families (Dong et al., 2020; Otero-Mayer et al., 2021, Soltero-Gozalez & Gillanders, 2021; Wendel et al., 2020; Yildirim, 2021). For example, Otero-Mayer et al. (2021) and Soltero-Gozalez and Gillanders, (2021) emphasized individualized cooperation between families and schools should be improved in pandemic and non-pandemic times especially considering the education level of families (e.g., highly educated families had more communication with the school than those families with less-educated parents). Additionally, studies recommended universal access to the internet and technological equipment (Otero-Mayer et al., 2021), educational opportunities through coaching of parents to increase child engagement and activities (Soltero-Gozalez & Gillanders, 2021; Wendel et al., 2020), and guidebooks and distance education specific to parent’s role in their child’s distance education (Yildirim, 2021).

Instituting System-Wide Changes

Most studies (n = 8; 62%) made recommendations for early education system change (Barret et al., 2021; Egan et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021; Quenzer-Alfred et al., 2021; Timmons et al., 2021; Wendel et al., 2020; Yildirim, 2021). For example, Quenzer-Alfred et al. (2021) suggested that education systems consider ECE programs critical institutions, thus suggesting that ECE remains open to prevent missed learning and opportunities for young children in future emergencies. Kim et al. (2021) recommended creating government policies on the implementation of virtual and distance learning specifically for young children in the case of future ECE closures. Additionally, several studies recommended policies to address equity, diversity, and inclusion in distance education delivery and technology platform use (Timmons et al., 2021; Yildirim, 2021).

Aiming toward a successful education system in early education, Barret and colleagues (2021) realized the importance of a trained and stable workforce. Additionally, these authors suggested that fragmentation within the ECE system be a focus (Barret et al., 2021). Timmons et al. (2021) suggested that one way to unite the system in supporting families included is providing an integrated care system that uses community services and partnerships (e.g., social work services, youth organizations, and food banks). Another example, described by Wendel et al. (2020), is encouraging school professionals to acknowledge various levels of adversity in families, and prioritizing those at highest risk.

Finally, two studies made recommendations around the importance of play in the education of young children (Egan et al., 2021; O’Keefe & McNally, 2021). Specifically, O’Keefe and McNally (2021) suggested a policy in ECE to include a plan for play to be incorporated upon return to school in light of COVID restrictions limiting sharing of materials and keeping a safe distance. Egan et al. (2021) added the recommendation of using play pods (e.g., small groups who remain together for a length of time) to decrease exposure to illness.

Discussion

Quality early childhood education is essential to school success. This review demonstrates the additional, unpredictable barriers emphasized by the COVID-19 pandemic from a global perspective. This review highlights the multiple risk factors (e.g., geographic isolation, developmental delays, and low socioeconomic status) that tend to increase the risk of academic failure for vulnerable populations of young children and their families. While the extent of this global crisis’ impact on early education is still unfolding, this scoping review synthesizes current research on teachers’, parents’, and children’s experiences during pandemic-related school closures. It provides essential recommendations for school adaptations and family support. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review of its kind in early childhood education and care (ECEC).

Limitations of Extant Literature

Despite the important outcomes presented in this review, there are limitations to the conclusions drawn here. The most prominent limitation of the current literature is the variability and unforeseen impact of COVID-19, especially the steady resurgence of the pandemic in countries around the world (World Health Organization, 2021). Thus, many perspectives may be missed, and comprehensive conclusions cannot be drawn because the pandemic is ongoing. However, that unfortunate fact makes the current review necessary—the recommendation from global researchers overwhelmingly suggests our current state in the new normal (Neece et al., 2020; Park et al., 2020). Future research should consider follow-up surveys to identify post-pandemic needs to include ways education systems did respond, the relative efficacy of various strategies, and the actions taken by nations around the world to quell the spread of the disease. Additionally, while the studies included various countries, many were not represented, or only a small number of participants were from that particular location (e.g., Atilles et al., 2021). Nonetheless, the overall sample represents an extensive set of participants from several countries worldwide.

A second limitation of the current group of studies is collecting data via email and the Internet. While some studies used face-to-face interviews (e.g., Quenzer-Alfred et al., 2021) or telephone interviews (e.g., Soltero-Gonzalez & Gillanders 2021), the majority of survey participants had access to the Internet and a technological device available to complete the survey, even during the pandemic. Therefore, it is possible that a survey of parents that was not reliant on the internet for dissemination and completion might have yielded different results. It is likely that households without internet and technology access did not complete the survey, nor were they able to access online, virtual learning opportunities for their child, creating an even larger equity gap. The one exception is Barret et al. (2021), who provided technology and Internet access to participants who needed it. However, the number of participants that partook in this offer was not reported (Barret et al., 2021).

A third limitation was the underrepresentation of fathers and male teachers. Despite studies representing diverse populations, most participants identified as female and mothers. A fourth limitation pertained to child outcomes. Only one study reported child-reported perspectives. Most studies relied on parent or teacher interpretations and reports of child impact. Future research could incorporate other indices of child behavior, including observation or direct assessment to better understand child outcomes.

Finally, there is minimal evidence that the recommendations made by a group of authors are transferrable by country and culture. For example, the United States has made strides in increasing internet access to rural families, and schools in some other nations issued technology tools to families. However, Kim et al. (2021) conducted their study in Ethiopia and many participants not only lacked access to technology devices and the internet but also were without electricity. The global health pandemic, with its reliance on technological alternatives, redefined basic needs in contemporary society when individuals and groups could not access the resources available.

Strengths of Extant Literature

There are at least five strengths of the extant literature. First, the studies presented a broad perspective from various countries around the world (see Table 25.1) providing evidence of the global impact of school closures on teachers and families. Yet, there were commonalities among the participating populations (e.g., difficulty in educating children at home and difficulty accessing technology) despite geographical separation. Second, several studies included novel outcomes based on child, parent, and teacher experiences during COVID-19 (e.g., importance of emphasizing play and struggles to assess child’s developmental gains). Third, these outcomes led to various recommendations to address specific issues of teacher preparation, support for children and families, and system changes for early education. Education systems can use these recommendations to improve early education and family support in future school closures either due to COVID-19 or unforeseen additional global events. Fourth, the studies took place at various timeframes across the pandemic, which provide a broader view of the impact due to COVID-19. Interestingly, the events described in this literature did not dramatically change throughout data collection periods despite some studies conducted during initial shutdown and other during the extended closures.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted ECEC across the globe, with lower income communities, children of color, and children with disabilities more impacted (Barnett & Jung, 2021; Neece et al., 2020). Although this scoping review reflects a snapshot of our current understanding of the pandemic’s impact on children’s early learning and school readiness, the impacts of the pandemic will likely unfold over years to come. The recommendations contained in the current group of reviewed articles are useful for the likely continued impact of the pandemic as well as other global disasters that challenge early education access. If early education is prioritized and viewed as essential, care can be reimagined to include a continuum of integrated services that relies on family–school partnerships, early education, and community services.

Statements and Declarations

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Oregon.

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Atiles, J. T., Almodóvar, M., Vargas, A. C., Dias, M. J., & Zúñiga León, I. M. (2021). International responses to COVID-19: Challenges faced by early childhood professionals. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 29(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2021.1872674

Barnett, W. S., Grafwallner, R., & Weisenfeld, G. G. (2021). Corona pandemic in the United States shapes new normal for young children and their families. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 29(1), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2021.1872670

Barnett, W. S., & Jung, K. (2021). Seven impacts of the pandemic on young children and their parents: Initial findings from NIEER’s December 2020 preschool learning activities survey. National Institute for Early Education Research. https://nieer.org/research-report/seven-impacts-of-the-pandemic-on-young-children-and-their-parents-initial-findings-from-nieers-december-2020-preschool-learning-activities-survey

Barnett, W. S., Jung, K., & Nores, M. (2020). Young children’s home learning and preschool participation experiences during the pandemic. NIEER 2020 preschool learning activities survey: Technical report and selected findings. National Institute for Early Education Research. https://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/NIEER_Tech_Rpt_July2020_Young_Childrens_Home_Learning_and_Preschool_Participation_Experiences_During_the_Pandemic-AUG2020.pdf

Dong, C., Cao, S., & Li, H. (2020). Young children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Chinese parents’ beliefs and attitudes. Children and Youth Services Review, 118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105440

Egan, S. M., Pope, J., Moloney, M., Hoyne, C., & Beatty, C. (2021). Missing early education and care during the pandemic: The socio-emotional impact of the COVID-19 crisis on young children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 925–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01193-2

Kim, J., Araya, M., Haili, B. H., Rose, P. M., & Woldehanna, T. (2021). The implications of COVID-19 for early childhood education in Ethiopia: Perspectives from parents and caregivers. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 855–867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01214-0

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BioMed Central Medical Research Methodology, 18(143). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2020). Developmentally appropriate practice [Position Statement]. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/dap-statement_0.pdf

Neece, C., McIntyre, L. L., & Fenning, R. (2020). Examining the impact of COVID-19 in ethnically diverse families with young children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 64(10), 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12769

O’Keeffe, C., & McNally, S. (2021). ‘Uncharted territory’: Teachers’ perspectives on play in early childhood classrooms in Ireland during the pandemic. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 29(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2021.1872668

Otero-Mayer, A., Gonzalez-Benito, A., Gutierrez-de-Rozas, B., & Velaz-de-Medrano, C. (2021). Family-school cooperation: An online survey of parents and teachers of young children in Spain. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 977–985. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01202-4

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Park, C. L., Russell, B. S., Fendrich, M., Finkelstein-Fox, L., Hutchison, M., & Becker, J. (2020). Americans’ COVID-19 stress, coping, and adherence to CDC guidelines. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(8), 2296–2303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05898-9

Quenzer-Alfred, C., Schneider, L., Soyka, V., Harbrecht, M., Blume, V., & Mays, D. (2021). No nursery ‘til school – the transition to primary school without institutional transition support due to the COVID-19 shutdown in Germany. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(1), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2021.1872850

Soltero-Gonzalez, L., & Gillanders, C. (2021). Rethinking home-school partnerships: Lessons learned from Latinx parents of young children during the COVID-19 era. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 965–976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01210-4

Steed, E. A., & Leech, N. (2021). Shifting to remote learning during COVID-19: Differences for early childhood and early childhood special education teachers. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01218-w

Timmons, K., Cooper, A., Bozek, E., & Braund, H. (2021). The impacts of COVID-19 on early childhood education: Capturing the unique challenges associated with remote teaching and learning in K-2. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 887–901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01207-z

Wendel, M., Ritchie, T., Rogers, M. A., Ogg, J. A., Santuzzi, A. M., Shelleby, E. C., & Menter, K. (2020). The association between child ADHD symptoms and changes in parental involvement in kindergarten children’s learning during COVID-19. School Psychology Review, 49(4), 466–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1838233

World Health Organization. (2021, July). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019?gclid=CjwKCAjwr56IBhAvEiwA1fuqGoJjinJCu7d2SgQ1pQZc-HaSOGyE-ei1UiN957Bcc9BK7oDUr44o-RoCJi0QAvD_BwE

Yildirim, B. (2021). Preschool education in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic: A phenomenological study. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 947–963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01153-w

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kunze, M., McIntyre, L.L. (2022). Will Programs Be Prepared to Teach Young Children At-Risk Post-pandemic? A Scoping Review of Early Childhood Education Experiences. In: Pattnaik, J., Renck Jalongo, M. (eds) The Impact of COVID-19 on Early Childhood Education and Care. Educating the Young Child, vol 18. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96977-6_25

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96977-6_25

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-96976-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-96977-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)