Abstract

Many children in out-of-home care experience significant early adversity prior to entering care, resulting in poorer educational, socio-emotional and health outcomes which have implications throughout their life trajectory. While the focus is often on children’s school performance and later life chances, cracks in the foundations of learning appear early. Children in care are already behind in their language, psycho-social and neuro-psychological functioning during the pre-school years and have poorer academic and socio-emotional competence on entry to school.

Given strong evidence that attending good quality early years provision can help disadvantaged children catch up with their peers, there is a good reason to believe that the same applies for children in care. Yet relatively little is known about the potential of early education as an intervention for children in care. This chapter reviews available evidence, drawing on a recent small-scale English research study. ‘Starting Out Right’ comprised a purposive review of relevant literature, interviews with a range of experts, and an online survey of English local authorities. This brief overview of study findings provides a summary of the review, followed by a case study of practice and policy in England designed to ensure that children in care have access to good quality early education, highlighting successes and areas for development to consider potential lessons for other countries.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Early education

- Quality of early years education

- Access to early years education

- Looked after children

- Early childhood

1 Setting the Scene: The Case for Early Intervention

Children in out-of-home care are those for whom the state assumes parental responsibility because the adults caring for them are no longer able to. Many experience significant early adversity prior to entering care, resulting in poorer educational, socioemotional and health outcomes, which have implications throughout their life trajectory. The most recent government data from England show that only 18% achieved a pass in English and mathematics at the end of compulsory schooling, as compared to 59% of children not in care (DfE, 2017a). Only 12% of care leavers progress to higher education compared to 42% nationally (Harrison, 2017). Similar trends are identified in other UK countries (Mannay et al., 2016; The Scottish Government, 2015) and internationally (Canada: Dill, Flynn, Hollingshead, & Fernandes, 2012; the US: Pecora, 2012; Australia: Jackson & Cameron, 2014).

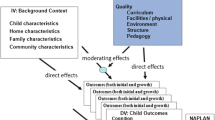

Although the starkest differences are often seen in secondary education and beyond, gaps emerge early. Children in care, particularly those who have been maltreated, show delays in their academic, socio-emotional and psychosocial competence between the ages of 3 and 6 years, with inhibitory control mediating relationships between maltreatment and academic and socio-emotional competence (Pears & Fisher, 2005; Pears, Fisher, Bruce, Kim, & Yoerger, 2010). This creates a strong case for early intervention. Attendance at preschool provision is now widely recognised as a means of helping disadvantaged children to catch up with their peers by providing a protective buffer against the detrimental effects of poor home environments (Berry et al., 2016; Sylva, Melhuish, Sammons, Siraj-Blatchford, & Taggart, 2010). Benefits have been identified in relation to cognitive, language, and social development, school success, employment and social integration (Melhuish et al., 2015), and are stronger and more sustained if provision is of good quality (Sylva et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2009).

This chapter focuses on the potential of early education as an intervention for children in care, drawing on a recent small-scale English research study funded by the Nuffield Foundation (Author, Hardy, Clancy, Dixon, & Harding, 2016). The Starting Out Right study aimed to:

-

Review relevant research evidence and current English policy

-

Establish what data are available on take-up of early education by children in care in England and on the quality of that provision, and the robustness of systems to promote access and quality and

-

Establish the views of stakeholders and experts on the importance of early education for children in care, the extent to which they currently have access to good quality early education in England, and how best to meet the needs of looked after children in early education settings.

The research comprised a purposive review of relevant literature, interviews with a range of experts (academics, health professionals, foster carers and the organisations representing them, representatives from early education providers, local authorities and central government) and an online survey of all 152 English local authorities (response rate 89%). The study received ethical approval from the University of Oxford Central University Research Ethics Committee. This brief overview of study findings provides a summary of the literature review, followed by a case study of practice and policy in England designed to ensure that children in care have access to good quality early education, highlighting successes and areas for development to consider potential lessons for other countries. Further detail and full references are provided in the original research report (Author et al., 2016).Footnote 1

2 Review of Research Literature

A recent systematic review of the demographic risks associated with children entering care identified a number of family-level factors including low socio-economic status, maternal age at birth, parental alcohol/substance abuse or mental illness, learning difficulties, membership of an ethnic minority group and single parenthood (Simkiss, Stallard, & Thorogood, 2013), which are also predictors of developmental delay (e.g. Berry et al., 2016; Sylva et al., 2010; Waldfogel & Washbrook, 2010). Many of these factors (e.g. abuse or neglect) are shared with other at-risk groups. Children in care also experience unique risk factors relating to removal from their home and potentially frequent care moves, which compound the developmental risks. As a result, many are behind in language, psycho-social and neuro-psychological functioning, and have poorer academic and socio-emotional competence than their peers, even before they reach school (Klee, Kronstadt, & Zlotnick, 1997; Pears & Fisher, 2005; Pears et al., 2010; Stahmer et al., 2005). A recent study found, for example, that more than half fall below the 23rd percentile for phonological awareness on entry to kindergarten (Pears, Heywood, Kim, & Fisher, 2011). These factors influence readiness for school, as well as later educational attainment, psychosocial adjustment and life outcomes. School mobility is a further factor contributing to poorer outcomes, both in terms of educational progress and difficulties in forming positive and trusting relationships with teachers and peers (O’Higgins, Sebba, & Luke, 2015; Pears, Hyoun, Buchanan, & Fisher, 2015; Grigg, 2012).

Evidence relating to disadvantaged children more broadly suggests that a prime factor in overcoming early adversity is a nurturing home environment, which promotes educational, as well as socio-emotional development. Although research evidence relating specifically to children in care is limited, we know that carers similarly play a vital role in providing nurturing, sensitive and stable environments which promote attachment security and later educational outcomes (Dozier, Chase Stoval, Albus, & Bates, 2001; Healey & Fisher, 2011; Lang et al., 2016; Sebba et al., 2015).

Alongside the home environment, there is a strong case for early intervention through high quality early education and care from age two and upwards, with benefits for cognitive, language and social development, school success, employment and social integration. The main feature of the literature specific to early education for children in care is its scarcity; but we can learn much from the broader literature on children at risk of developmental delay (e.g. children experiencing poverty). For this group, there is strong evidence that early education before starting school can help children to catch up with their peers (Sylva et al., 2010). Given that similar factors are predictors of children entering public care (Simkiss et al., 2013), there is reason to believe that early education may also have potential for this group; although their unique risks factors mean that caution is needed when generalising. The case for early education is supported by the one care-specific study identified in our review, which found that enrolment of young foster children in accredited early years provision predicted better cognitive outcomes in primary school (Kaiser, Katz, Dinehart, & Ullery, 2011). A preschool intervention in the US designed to enhance school-readiness for children in care has also shown moderate but positive effects on literacy and self-regulation skills. Kids in Transition to School targeted early literacy, pro-social and self-regulatory skills during the summer prior to, and the first 2 months of, kindergarten (Pears et al., 2013). Group sessions for carers also encouraged their involvement in early literacy and their child’s education more widely. Finally, there is tentative evidence that preschool attendance may support carers and reduce the likelihood of placement breakdown (Meloy & Phillips, 2012a, 2012b).

Though the benefits of early care and education are potentially great, the unique risk profile of children in care makes them particularly vulnerable to variations in the quality and stability of educational provision. The wider literature on disadvantaged children shows that low quality education and care is associated with null – or even negative – effects, which represents a dual risk for children already prone to delayed development (Melhuish et al., 2015; Phillips & Lowenstein, 2011). We also know that children are more likely to maintain secure and stable attachments to early education providers if those providers do not change, and that instability of education and care can negatively affect children’s socio-emotional and language development, the security of their attachments with caregivers and their interactions with peers (see Author et al., 2014 for a review). A recent study on fostered children aged between 3 and 6 years found that those who moved their education placement more often had poorer socio-emotional competence (Pears et al., 2015). Both quality and stability of early education are therefore of prime importance. A third key factor is the involvement of carers in children’s early education and schooling. There is some evidence that maltreated foster children whose carers are involved with their early education have better socio-emotional outcomes (Pears et al., 2010), with involvement fully mediating the association between socio-emotional competence, maltreatment and foster placement. The same study also found that foster carers tend to be less involved in children’s schooling than the birth parents of non-fostered children, indicating that strategies to support involvement may be a promising target for intervention.

In summary, there is an emerging case for early intervention through high quality, consistent preschool experiences with strong links to carers and the home, although more research is needed to strengthen the case and add to the sparse existing literature. Further work is also needed to identify the extent to which children in care currently have access to good quality early education and care. While there is some evidence that this group is less likely to attend early years provision than children not in care, little is known about attendance patterns, influences on take-up or quality of experience. The Starting Out Right study aimed to address some of these gaps in knowledge through exploratory work in the English context, described in the following sections.

3 Current Policy in England Relating to Early Education for Children in Care

Of the more than 70,000 children in care of the state in England, approximately one fifth are under the age of five. These young children are placed largely in foster or kinship care (with a relative or friend) rather than in residential children’s homes. The majority – 61% – enter care following abuse or neglect (DfE, 2017b), with a further entering care following family dysfunction (15%), due to acute family stress (8%) and due to absent parenting (7%).

There has been an increasing recent focus in England on the educational attainment of this vulnerable group. High-profile research by the Universities of Oxford and Bristol (Sebba et al., 2015) has confirmed that children in care tend to have significantly poorer educational outcomes than their peers throughout school, with the gap widening as children get older. A number of notable moves have also taken place at policy level. Under the Children Act 1989, local government authorities are required to safeguard and promote the welfare of all children in care. The 2004 Children Act added an explicit duty to promote their educational attainment, and the Children and Families Act 2014 introduced a requirement for every local authority in England to appoint a ‘virtual school head’. This officer has a statutory responsibility to promote the educational achievement of children in care, monitoring and tracking their progress as if they were attending a single school. Virtual school heads liaise with the local authority social care and education teams, independent reviewing officers and education providers to ensure that appropriate provision is arranged at the same time as a care placement, and that children’s educational needs are met.

Children in care are also entitled to receive free early education from the age of 2 years. All 3-and-4-year-olds can access a universal entitlement of 15 h per week,Footnote 2 and the 40% most disadvantaged children (including all children in care) can do so from the age of two. From the September following their fourth birthday, all children in England are entitled to a full-time place in a primary school reception class.

Preschool children in care accessing early education must also have a Personal Education Plan (PEP). State-maintained schools and nurseries are required to appoint a designated teacher to promote the educational attainment of children in care, and lead on the development and review of PEPs (DCSF, 2009). An Early Years Pupil Premium is available to all education and care providers catering for disadvantaged children, equivalent to approximately £300 per annum for a child accessing their full placement hours. Finally, the national regulatory body (Ofsted) considers the extent to which support for the educational attainment of children in care is monitored as part of its inspection of early years providers and local government authorities.

4 Access to Early Education for Young Children in Care

So, with all these measures in place, what is the picture for young children in care in England? This section draws on an online survey of all 152 local authorities in England (response rate 89%) and 23 interviews with key stakeholders and experts, to consider the evidence. Interviews were conducted with early education providers and local government authorities identified as reflecting aspects of good practice, as well as with carers, healthcare professionals, academics, central government representatives and thirdsector organisations working to improve experiences for children/carers.

Access to good quality early education provision – and a focus on learning alongside emotional needs – were seen as paramount. Early years provision was considered to provide valuable opportunities to mix with peers, support for speech, language and learning, support with personal care routines, and early identification of potential delays. However, interviewees also recognised that attendance patterns may need to be more individualised than for children not in care, and that delayed entry may be appropriate for some, for example where time is needed to form a bond with their carer. Decision-making was understood to be complex and require consideration on a case-by-case basis.

Take-up of early education nationally is high: 68% for eligible 2-year-olds, 93% for 3-year-olds and 97% for 4-year-olds at the time the research was conducted (DfE, 2016). While it proved challenging to gather data from local authorities on take-up by children in care – an issue discussed further below – the survey indicated that rates are at least 14% lower than in the general population, with considerable variation between areas. Given that these data were drawn only from local authorities which kept interpretable records on take-up, the true gap may be larger. This is consistent with rates reported in national surveys for other disadvantaged groups, for example 80% for low income households as compared with rates of 94% or more for wealthy households (Brind, McGinigal, Lewis, & Ghezelayagh, 2014).

In some cases, for example where children are severely traumatised, non-attendance or reduced hours may be appropriate. However, it is unlikely that lower take-up is solely due to sensitive and informed decisions being made regarding children’s needs. A number of potential barriers to take-up were identified by interviewees, including low prioritisation of early education by social care teams and foster carers. This was exacerbated by practical barriers such as the large number of meetings foster carers might need to attend in relation to the children in their care (e.g. meetings with social care teams), and the often short-term and unpredictable nature of placements, with both factors thought to reduce the likelihood of foster carers prioritising attendance at an early education setting, and managing to find an available place at short notice. Early education providers interviewed for the research reported working with foster carers to hold places open for children while care placements were being set up, and to offer sessions at short notice when carers needed to attend a meeting or make a court appearance, but noted the need for flexibility in local authority funding of education placement to support this approach. High rates of special needs among children in care also raised challenges in terms of finding an appropriate early education setting, and ensuring that settings are prepared to meet children’s needs.

Several of the local authorities interviewed provided excellent examples of training for foster carers to raise awareness of the benefits of high-quality early education, and close liaison with social care teams and foster carers to organise access to suitable provision. However, these practices were by no means universal, largely because the majority of local authorities do not yet have a designated early years lead within the virtual school. This is an obvious target for improving future practice in England and would be supported by a strengthening of local authority statutory responsibilities to explicitly include the educational attainment of children in care prior to school-age.

Finally, our research indicated that monitoring of early education take-up is an important area for attention. As already noted above, although some form of response was received from 89% of local authorities, these were returned in widely varying formats and levels of detail, and some local authorities kept no data at all. A corresponding lack of national data on take-up, on the quality of settings attended, and on the educational attainment of children in care prior to statutory school age, makes evaluating – and thus ensuring – these aspects very difficult. A common data collection framework and expectation on local authorities to track uptake and attendance for collation at national level would be of great benefit, enabling access to high-quality provision to be monitored and – ultimately – ensured.

4.1 Quality of Early Years Education

If it is to succeed in supporting children in care to reach their full potential, early education provision must be of the highest quality. Interviewees were united in their view that a skilled and knowledgeable staff team was the cornerstone of quality for children in care. Practitioners were considered to need a good knowledge of attachment and the potential consequences of early trauma, the skills to support potentially diverse additional needs and to collaborate with carers and, ideally, experience in negotiating the system surrounding children in care. The importance of access to appropriate support and supervision to help staff in meeting any challenges was also highlighted. These requirements were not considered to be unique to children in care but to be more important for this group.

Flexibility in staffing was also required to provide individual support, to meet specific needs when problems arose, and to allow time for staff to attend meetings with carers and other professionals. Other components of quality included strong partnerships with other professionals (e.g. health teams), access to specialist interventions and therapies where needed, and close monitoring of progress in all aspects of development.

The local authority survey suggested that 89% of children in care receiving the free entitlement do so in provision graded as ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ by the national regulator Ofsted, which is broadly comparable to national trends. However, given the greater need for high quality provision among this group, there are still significant improvements which could be made: 11% attend provision graded as ‘requires improvement’ or ‘inadequate’.

And given the necessarily broad nature of Ofsted inspections (Author, Singler, & Karemaker, 2012) and the specific needs of children in care, it could also be argued that a higher quality bar is required. Although the Ofsted framework for inspections includes a requirement on children in care, it is not possible within the broad remit of inspections to consider this provision in detail. It may be, therefore, that a significant proportion of otherwise ‘good’ providers are not fully equipped to meet the needs of these children.

This was confirmed by interviewees. Some excellent examples of effective and individualised practices were identified in the research. State-maintained providers – nursery schools in particular – were considered to be particularly suited to meeting the needs of young children in care. Factors included experience with children at risk of developmental delay and their families, well-qualified and experienced staff teams, and access to specialist services. However, interviewees reported that this was not consistent across all provision attended by children in care. While excellent examples were found in the private and not-for profit sector, many were reported to lack the qualifications, training and experience required. This is consistent with previous research showing that quality is highest in the maintained sector, and that disadvantaged children attending private and voluntary sector settings are less likely to experience good quality than their more advantaged peers (Author & Smees, 2014; Sylva et al., 2010).

An obvious conclusion in policy terms is that preschool children in care in England should attend only providers graded as ‘good’ or higher by Ofsted and/or receive their early education within the state-maintained sector.Footnote 3 The reality, however, may not be so straightforward and interviewees warned against blanket policy-making. Some geographical areas have little state-maintained provision, particularly for 2-year-olds, where the free entitlement is primarily offered by private and non-profit providers. And although state maintained provision is of higher quality overall, there is variation within all sectors and excellent examples of practice were identified within a broad range of providers. Families may express a preference for a specific provider and retain the final decision. Lastly, there may be tensions between the twin needs for quality and stability. We know from research that moves between educational settings can be damaging, and interviewees also highlighted the important role played by early years providers in offering continuity and stability for children moving between placements. There may be a need to take continuity into account where, for example, a child is already attending early years provision considered to be of insufficient quality on entry to care and/or where a provider is downgraded from ‘good’ to a lower inspection grade. Although efforts should be made to place children in provision already known to offer excellent practice for children in care, further effort is also needed to ensure wider workforce preparedness.

4.2 Workforce Preparation

The local government authorities involved in our research provided good practice examples of training and preparation for early years practitioners to support them in meeting the needs of children in care. These efforts were largely led by designated early years representatives within virtual schools, in partnership with local authority early years teams. Examples included bespoke training on attachment and trauma, and virtual school early years leads providing a bridge between carers, social care teams and education/care providers to support choice of appropriate provision, clarify roles and responsibilities, support providers in meeting children’s needs and monitor progress through the use of PEPs. As noted above, the explicit designation of an early years lead within each virtual school – supported by the strengthening of statutory responsibilities – would enable the good practices highlighted in this research to become more widespread.

The second key area for attention is that of funding, required by early years providers to pay for extra training, staff replacements to allow time off for training and to attend meetings, and any specialist interventions required to meet the needs of children in care. Although the £300-per-annum Early Years Pupil Premium provides a good foundation, it was not considered by interviewees to be sufficient, particularly for providers with small numbers of eligible children or where children attend fewer than 15 h (since the premium is reduced accordingly). School-age children attract a much larger (£1900 per year) premium, set at a higher rate in recognition of the enduring impact of trauma in the lives of children in care. Adopting the same model for early education in England would enable providers to offer more effective early intervention.

In addition to being affordable, suitable training for early years practitioners also needs to be available. Here we face the challenge of identifying who needs to know what. We identified some excellent examples of specific training for practitioners, for example in York, where multiple staff from each early education and care provider receive bespoke professional development. However, given that many providers will rarely or never provide for a child in care, what level of specialist preparation is appropriate? Training is expensive and can be wasted without an opportunity to put knowledge into practice relatively soon after taking part. A sensible compromise would involve ensuring a basic level of knowledge for all practitioners, supplemented by access to specialist knowledge where required. Foundational preparation can be offered locally through high-quality training, and could also be opened to carers and local authority social care teams to support effective home learning environments and raise awareness of the benefits of high quality early years provision. In York, for example, foster carers are routinely included in the planning for early years training. Such training would improve outcomes for all disadvantaged children (indeed, all children) and help to ensure that access to early education is prioritised for children in care. Including the basic components of child development training in initial practitioner qualification is also essential.

Practitioners catering for children in care will also need access to specialist knowledge and appropriate supervision and support structures. A number of different potential models for achieving this were identified within the research. Some state maintained and not-for-profit nursery schools had in-house teams with specialist knowledge, including staff with a background in social work and strong supervisory and support structures. A number of peer support models were also identified, including a nursery school funded by the local authority to support local schools and early education providers, and a community partnership model facilitated by the local authority which enabled providers to access expertise from others with relevant experience. Given increasing moves towards a sector-led improvement model in England, policy makers at national and local level will need to consider how existing expertise and networks can be built upon to provide access to specialist knowledge and supervision where needed.

4.3 Joined-Up Working

The importance of multi-disciplinary working in meeting the needs of children in care was identified frequently by interviewees. Universal health visiting services have a key role to play throughout children’s lives and – in England – an integrated health and early education review at age two provides an effective means of sharing information on health needs with both carers and early years providers. Virtual schools are well-placed to promote professional collaboration between local authority early years and social care teams, carers, health professionals and early education providers. Collaboration on decision-making at commissioning level is also important. Decisions should take into account the needs of the child across all areas of development, and balance the twin requirements of high quality and stability in early years provision for children in care.

Finally, out-of-area care placements requiring liaison between local authorities were found to create a significant barrier to children’s access to high quality early education in England. Findings suggest that many local authorities are not aware of children that have been placed in their area. Likewise, the placing local authority may not be aware of the best providers and available support services to support the child’s early education.

5 Implications for Research, Policy and Practice

The Starting Out Right research made a small step towards addressing the significant gaps in knowledge relating to the early years experiences of children in care. This chapter has focused on the potential of early education as an early intervention for children in care, and considered implications for practice and policy in England. Although country-specific, there is much to be learned for policy and practice more broadly, both from the good practice identified in England, and from the areas identified as needing further attention. Key messages include:

-

A clear government commitment at policy level to the education of children in care prior to school-age, including a requirement on local government and early years providers to ensure that needs are addressed, and some form of regulation to ensure that responsibilities are enacted

-

A co-ordinating body at local level with responsibility for promoting the educational attainment of young children in care within the area (the role played by Virtual School Heads in England) which explicitly includes the preschool period

-

Efforts to raise awareness among carers and social care teams about the benefits of good quality early education and care

-

Support for early education providers to develop the necessary expertise, offer flexible provision, liaise with health and social care teams and access specialist support services where needed

-

Adequate funding for workforce preparation and to enable providers to meet the often specific and significant additional needs of children in care

-

A multi-disciplinary approach involving collaboration at all levels between education, health and social care

-

Decision-making regarding children’s access to early education which is informed by all three disciplines, and which balances the dual needs for quality and stability and

-

Data collection and monitoring at national and local level regarding take-up of early education by preschool children in care, quality of provision attended and educational attainment.

Further research is also required in this important area to establish a more robust evidence-base in relation to early education and children in care. Meloy and Phillips (2012a, 2012b) identify three clear stages for future work:

-

Describing patterns of use, including timing, amount and type of provision

-

Identifying the predictors of take-up and use (including both child and carer characteristics) and

-

Exploring the effects of early years provision on looked after children in different aspects of development, including variation in effects according to provision type, amount, stability and quality.

Co-ordinated efforts to develop knowledge in these areas will help to ensure that the full potential of preschool education as an early intervention for children in care is both understood and realised.

Notes

- 1.

For brevity, full references have not been included in this summary but are provided in Starting Out Right (Author et al., 2016). http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/looked-afterchildren-england

- 2.

At the time of writing, while working parents who meet specific income and eligibility criteria are entitled to a further free 15 h for 3 and 4-year-olds, foster carers are not eligible to apply.

- 3.

Disadvantaged children are in fact already disproportionately represented within maintained provision.

References

Author, S., Eisenstadt, E., Sylva, K., Soukakou, E., & Ereky-Stevens, K. (2014). Sound foundations: A review of the research evidence on quality of early childhood education and care for children under three implications for policy and practice. London: Sutton Trust.

Author, S., Hardy, G., Clancy, C., Dixon, J., & Harding, C. (2016). Starting out right: Early education and looked after children. Family and Childcare Trust [online]. https://www.familyandchildcaretrust.org/starting-out-right-early-education-andlooked-after-children-0. Accessed 27 June 2018.

Author, S., Singler, R., & Karemaker, A. (2012). Improving quality in the early years: A comparison of perspectives and measures. London/Oxford: University of Oxford and Daycare Trust.

Author, S., & Smees, R. (2014). Quality and inequality: Do three and four-year-olds in deprived areas experience lower quality preschool provision? London: Nuffield Foundation.

Berry, D., Blair, C., Willoughby, M., Garrett-Peters, P., Vernon-Feagans, L., Mills-Koonce, W. R., et al. (2016). Household chaos and children’s cognitive and socio-emotional development in early childhood: Does childcare play a buffering role? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 34, 115–127.

Brind, R., McGinigal, S., Lewis, J., & Ghezelayagh, S. (2014). Childcare and early years providers survey 2013 [online] (Report Reference: JN117328). Department for Education. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/355075/SFR33_2014_Main_report.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2018.

DCSF. (2009). Improving the attainment of looked after children in primary schools: Guidance for schools [online] (Report Reference: DCSF-01047-2009). https://www.brighton-hove.gov.uk/sites/brightonhove.gov.uk/files/Improving%20attainment%20for%20LAC%20in%20Primary.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2018.

Department for Education. (2016). Provision for children under five years of age in England, January 2016 [online] (Report Reference: SFR 23/2016). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/532575/SFR23_2016_Text.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2018.

Department for Education. (2017a). Outcomes for children looked after by local authorities in England, 31 March 2017 [online] (Report Reference: SFR 20/201). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/695360/SFR20_2018_Text__1_.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2018.

Department for Education. (2017b). Children looked after in England (including adoption) year end 31 March 2017 [online] (Report Reference: SFR 50/2017). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/664995/SFR50_2017-Children_looked_after_in_England.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2018.

Dill, K., Flynn, R. J., Hollingshead, M., & Fernandes, A. (2012). Improving the educational achievement of young people in out-of-home care. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(6), 1081–1083.

Dozier, M., Chase Stoval, K., Albus, K. E., & Bates, B. (2001). Attachment for infants in foster care: The role of caregiver state of mind. Child Development, 72(5), 1467–1477.

Grigg, J. (2012). School enrolment changes and student achievement growth: A case study in educational disruption and continuity. Sociology of Education, 85, 388–404.

Harrison, N. (2017). Moving on up: Pathways of care leavers and care-experienced students into and through higher education. http://www.nnecl.org/resources/moving-on-upreport?topic=guides-and-toolkits. Accessed 14 July 2018.

Healey, C. V., & Fisher, P. A. (2011). Young children in foster care and the development of favourable outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 1822–1830.

Jackson, S., & Cameron, C. (2014). Improving access to further and higher education for young people in public care: European policy and practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Kaiser, M. Y., Katz, L., Dinehart, L., & Ullery, M. A. (2011). Developmental outcomes of children within and outside the child welfare system: An examination of the impact of childcare quality and family stability on developmental status. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development (2011) Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Google Scholar.

Klee, L., Kronstadt, D., & Zlotnick, C. (1997). Foster care’s youngest: A preliminary report. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 6(2), 290–299.

Lang, K., Bovenschen, I., Gabler, S., Zimmerman, J., Nowacki, K., Kliewer, J., et al. (2016). Foster children’s attachment security in the first year after placement: A longitudinal study of predictors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 36, 269–280.

Mannay, D., Staples, E., Hallett, S., Roberts, L., Rees, A., Evans, R., & Andrews, D. (2016). Exploring the educational experiences and aspirations of looked after children and young people (LACYP) in Wales (CASCADE Research Briefing, Number 7) [online]. http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/cascade/files/2014/10/Briefing-7.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2018.

Melhuish, E., Ereky-Stevens, K., Petrogiannis, K., Aricescu A. M., Penderi, E., Tawell, A., et al. (2015). A review of research on the effects of early childhood education and care (ECEC) on children’s development (CARE Report). http://ececcare.org/fileadmin/careproject/Publications/reports/new_version_CARE_WP4_D4_1_Review_on_the_effects_of_ECEC.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2018.

Meloy, M. E., & Phillips, D. A. (2012a). Foster children and placement stability: The role of child care assistance. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 33(5), 252–259.

Meloy, M. E., & Phillips, D. A. (2012b). Rethinking the role of early care and education in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 882–890.

O’Higgins, A., Sebba, J., & Luke, N. (2015). What is the relationship between being in care and the educational outcomes of children? An international systematic review [online]. Oxford: Rees Centre for Research in Fostering and Education. http://reescentre.education.ox.ac.uk/wordpress/wpcontent/uploads/2015/09/ReesCentreReview_EducationalOutcomes.pdf

Pears, K. C., Fisher, H. K., Bruce, J., Kim, P. A., & Yoerger, K. (2010). Early elementary school adjustment of maltreated children in foster care: The roles of inhibitory control and caregiver involvement. Child Development, 85(5), 1550–1564.

Pears, K. C., & Fisher, P. A. (2005). Emotion understanding and theory of mind among maltreated children in foster care: Evidence of deficits. Development and Psychopathology, 17(1), 47–56.

Pears, K. C., Fisher, P. A., Kim, H. K., Bruce, J., Healey, C. V., & Yoerger, K. (2013). Immediate effects of a school readiness intervention for children in foster care. Early Education and Development, 24(6), 771–791.

Pears, K. C., Heywood, C. V., Kim, H. K., & Fisher, P. A. (2011). Pre-reading deficits in children in foster care. School Psychology Review, 40(1), 140–148.

Pears, K. C., Hyoun, K. K., Buchanan, R., & Fisher, P. A. (2015). Adverse consequences of school mobility for children in foster care: A prospective longitudinal study. Child Development, 86(4), 1210–1226.

Pecora, P. J. (2012). Maximising educational achievement of youth in foster care and alumni: Factors associated with success. Children and Services Review, 34, 112–1129.

Phillips, D. A., & Lowenstein, A. E. (2011). Early care, education, and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 483–500.

Sebba, J., Berridge, D., Luke, N., Fletcher, J., Bell, K., Strand, S. & O’Higgins, A. (2015). The educational progress of looked after children in England: Linking care and educational data [online]. http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/sites/default/files/files/EducationalProgressLookedAfterChildrenOverviewReportNov2015.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2018.

Simkiss, D. E., Stallard, N., & Thorogood, M. (2013). A systematic literature review of the risk factors associated with children entering public care. Child: Care, Health and Development, 39(5), 628–642.

Smith, R., Purdon, S., Author, S., Sylva, K., Schneider, V., La Valle, I., et al. (2009). Early education pilot for two year old children evaluation (DCSF Research Report RR134).

Stahmer, A. C., Leslie, L. K., Hurlburt, M., Barth, R. P., Webb, M. B., Landsverk, J., et al. (2005). Developmental and behavioral needs and service use for young children in child welfare. Paediatrics, 116, 891–900.

Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (Eds.). (2010). Early childhood matters: Evidence from the effective pre-school and primary education project. London: Routledge.

The Scottish Government. (2015). Getting it right for looked after children and young people: Early engagement, early permanence and improving the quality of care [online]. Open Government. http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0048/00489805.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2018.

Waldfogel, J., & Washbrook, E. V. (2010). Low income and early cognitive development in the UK. A report for the Sutton Trust. London: Sutton Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mathers, S. (2019). Early Education as an Intervention for Children in Care. In: McNamara, P., Montserrat, C., Wise, S. (eds) Education in Out-of-Home Care. Children’s Well-Being: Indicators and Research, vol 22. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26372-0_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26372-0_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-26371-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-26372-0

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)