Abstract

Water and Sanitation in Solomon Islands is a sector that really needs attention, as water and sanitation services are lacking in many provinces. Some impact stories from the rural development program (RDP) are presented as baseline information.

To support the achievement of SDG 6 targets in “clean water and sanitation,” Solomon Islands has introduced the National Water Resource and Sanitary (WATSAN) Policy in 2017 and WATSAN Implementation Plan 2017–2033. The Government of Solomon Islands signed a Financing Agreement for €17.4 million with the European Union for “improving governance and access to water, sanitation and hygiene promotion (WASH) for rural people.” As a result, the rural WASH Program, now commonly known as RWASH Program was initiated. Improving health through community participation in RWASH project in Solomon Islands is discussed and achievements in water and sanitation for the period 2016–2020 are presented. In 2020, nationally, the population using an improved drinking water was at 73%, whereas the proportion of the population using an improved sanitation facility was 40.6% in the Solomon Islands.

The Rural WASH Strategic Plan 2015 to 2019 has set targets for improving access to water, sanitation (open defecation free, ODF), and hygiene services and includes both 5-year and 10-year targets. It is apparent now that the water target for 2019 was set too low at 52% but achieved 65.9% already in 2018 but no further progress made throughout 2019 and 2020, remaining at 65.9%. All three of the targets are extremely ambitious for 2024 at 100% or near 100%.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

10.1 Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is consisting of over 900 smaller islands and six major Islands is located in the South Pacific Oceans on the east of Papua New Guinea, with a total area of 28,370 square kilometers with an Exclusive Economic Zone of 1.3 million square kilometers. The area includes both mountainous and volcanic islands as well atolls and “artificial” islands built by the indigenous people in the lagoons. The large islands and many of the small islands including the atolls and artificial islands are inhabited. Its capital is Honiara, which is situated within the main province of Guadalcanal. There are eight other provinces: Malaita, Western, Rennell and Bellona, Central, Makira-Ulawa, Choiseul, Isabel, and Temotu. It has rich natural resources, in particular forests, freshwater, marine and fishery resources, agricultural land and minerals potential as well as beautiful environment. However, the forest resources are rapidly draining, caused by commercial logging at unsustainable rates (Fig. 10.1).

Map of Solomon Islands (Mishra, Hargreaves, and Moretto, 2010)

Total population in Solomon Island in 2019 predicted was 712,455, with the national population density being 24 people per km2. However, there are parts of the country which are relatively densely populated, such as Central Province (49 people per km2), Malaita Province (41 people per km2), and Guadalcanal (29 people per km2). As the capital city Honiara is the highest density area, with the density level of 5950 people per km2. Based on the geographical distribution, 24% of the population lives in urban areas and 76% lives in rural areas. Statistic data show that the urban population has been increasing rapidly due mainly to people moving from rural areas to the urban centers, especially Honiara. Table 10.1 provides some data at a glance.

10.2 Water and Sanitation in Solomon Islands

Water and Sanitation in Solomon Islands are a sector that really needs attention as these services are not yet covered to all of the areas in Solomon Islands. The disparity of water and sanitation services between urban and rural areas is very significant. In 2009 approximately 45% of urban households and only 3% of rural households had access to private flushing toilets. In 2016, 80% of rural households (>300,000 people) practiced open defecation. Nearly 13% of rural households (~50,000 people) had access to improved sanitation that hygienically separates human excreta from human contact (SPREP, 2019).

The treated water supplied by the Solomon Islands Water Authority (SIWA) is only available in the urban area (Figs. 10.2 and 10.3) such as Honiara, Noro Town in the Western Province, Auki Town in Malaita Province, and Tulagi Town in the Central Province. Most of the rural area utilize groundwater and rainwater for their water supply. The rural areas collected water from the dug wells for washing and bathing as the water quality of groundwater is relatively poor due to salinity and they use the rainwater for drinking and cooking.

Solomon water area of operation (Hunterh2o, 2017)

Existing serviced and un-serviced areas by SIWA in Honiara (Hunterh2o, 2017)

The water supply systems in urban centers in Solomon Islands consist of the following: (a) Source (Springs or Bores), (b) Pump Facilities, (c) Disinfection Facility, (d) Water Reservoirs, (e) Water Mains, and (f) Water Distributions. Meanwhile for rural area excluding provincial towns and development centers that may be classed as urban; various types of water supply systems have been tried such as: (a) Gravity Feed Systems, (b) Rain Harvesting Systems, and (c) Hand Dug Wells or Natural Water Holes with the use of Hand Pumps, subject to the geographical nature of Solomon Islands. The gravity feed systems are commonplace particularly where rivers, streams, and springs are plentiful and only practicable on the raised islands (main islands). Gravity fed systems are usually used by individual rural villages and sometimes by community villages. At present most rural communities can access water by stand-alone reticulated systems; however, other community villages still rely on un-reticulated natural streams and springs.

The freshwater in Solomon Islands is used for:

-

1.

Drinking and household use: both in villages and in urban centers, demand for drinking and household use of water is increasing with the population growth, and from this phenomenon usage of water will also increase at a faster rate in the future for urban and rural populations. The purified drinking water in Solomon Islands is still quite expensive compared to other countries in the South Pacific. Urban and peri-urban settlements in Honiara have limited access to water, a study found out that 92% of informal settlements did not have access to water services by Solomon Water as their location is on marginal land including riverbanks, steep gullies, and mangrove swamps. As a result no legal pipe connections are provided to the area and most households cannot afford the connection fees and tariffs as the price of treated water in Solomon Islands is quite high. The average household monthly wage in the settlements is about SI$632 [US$83] and connection fees are between SB$975 and SB$3380 [US$125.98 to US$450], which is significantly more than an entire month’s income (Hunterh2o, 2017).

UN-Habitat through the Participatory Settlement Upgrading Program (PSUP) was trying to escalate the water service in the urban areas, and World Vision as one of the NGOs in Solomon Island also assists by providing water in some informal settlements like Burns Creek, but is not active in all settlements. Some NGOs focus on water provision to rural areas because of some problems in the informal settlement in urban area such as social and cultural heterogeneous, densely populated, and also the conflict of land tenure (Hunterh2o, 2017). Solomon Islands Water Authority (SIWA) recently provided the communal connections in at least one informal settlement, on the Burns Creek for 360 households with the three connection communal taps which managed by community leaders and eventually it ended up with the disconnection as the community could not manage to pay the water bills (Hunterh2o, 2017).

-

2.

Industrial use: Although demands are still relatively small there is considerable potential for future growth, the water quality can be an important factor in industrial uses.

-

3.

Agricultural use: Surface water and groundwater will be the main sources used in the farms in the future, by using irrigation systems. The heavy capital expenditure required for irrigation works makes accurate assessment of the flow from the primary sources very important. While most crops are rainfed and agricultural developments can be seen in Guadalcanal and other high islands in the Solomon Islands.

-

4.

Power generation: The nation’s rivers are an important source of renewable indigenous energy. At the moment there is limited hydropower development in Solomon Islands. There is only a single micro-hydropower (150 kW) and about a dozen pico-hydropower installations in the rural areas to date which can sustain a small community.

Pipe sewerage is also not yet covered in all urban areas, some of the residents are using the on-site sanitation facilities, but rely on closed tanks (often intended to be septic tanks, but with inadequate or no drain fields) and pits for containment as the sewerage system only provided for formal areas (Schrecongost et al., 2015). There are two types of wastewater disposal systems identified in urban centers, there are: (1) conventional gravity sewerage system and (2) septic tanks. Flush toilets are used in the urban centers with gravity sewage systems or septic tank systems. Honiara is the only urban area that has a gravity sewerage system with a 30% coverage area. There are 16 sewerage systems, and each system is serviced with an outfall in the ocean. The composition of wastes is mostly domestic. The Environmental Health Division lacks the political motivation or allocated resources to monitor and enforce the installation or operating standards of these on-site facilities in urban areas. H2o team reported that most settlers depend largely on pit latrines, may have septic tanks, or openly defecate in the bushes, creeks, or the beach. Settlers often buy and build toilets themselves; multiple households may pool resources to build a shared facility. There are no effective guidelines, assistance, or monitoring of these toilets or the installation process. As the sanitation service did not generate revenue it creates the status quo and becomes the marginal service (Hunterh2o, 2017). Rural communities around the Solomon Islands have modest wastewater systems such as soak-pits usually located on-site to drain wastewater at household or public stand taps.

10.3 Baseline Studies of the Wash Indicators in Solomon Islands

Under the MDGs, improved access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation target was divided into two indicators: (1) Proportion of population using an improved drinking water source and (2) Proportion of population using an improved sanitation facility (Mishra, Hargreaves, and Moretto, 2010). Based on the MDG targets (Fig. 10.4), Solomon Islands provided improved drinking water for more than half of the population during 2000–2015, although there has been a 0.58% per year decrease in the coverage at the national level over the 15 years.

Proportion of Solomon Islands’ population using an improved drinking water 2000–2015 (WHO/UNICEF JMP, 2019)

In urban areas the proportion of improved drinking water coverage increased marginally by 0.07% per year and the coverage decreased by 0.83% per year in rural areas. Compared to the population growth of 2.3% per year in 2016, Solomon Islands needed to speed up the service of improved drinking water coverage to stay on track with MDG targets.

Figure 10.5 indicates that Solomon Islands has 76–90% coverage for improved drinking water in 2015, higher than Papua New Guinea and Kiribati but still lower than other Pacific Islands’ countries.

According to Fig. 10.6, from years 2000 to 2015, Solomon Islands was lagging behind the MDG target 7c for improved sanitation. Nationally, the above data shows that in 2020, only 37.1% of the population had access to an improved sanitation service against the targetted 50%. Furthermore, Fig. 10.6 also shows the disparity of improved sanitation service between rural and urban area. About 94.1% of urban population had access to improved sanitation, but in rural areas it was only 20.7% in 2015.

Proportion of Solomon Islands’ population using an improved sanitation 2000–2015 (WHO/UNICEF JMP, 2019)

As can be seen in Fig. 10.7, compared to other Pacific Island Countries, the Solomon Islands achievement in provide the improved sanitation was low, with the coverage in the range 26–50%, same level with Kiribati, Nauru and Federation State of Micronesia (FSM). The improved sanitation coverage of Solomon Island is lower than Fiji, Tongam Samoa, Cook Islands, and Palau.

10.3.1 The Rural Development Program (RDP) and Some Impact Stories

The purpose of Rural Development Program is twofold:

-

1.

Community Infrastructure and Services: To improve basic infrastructure and services in rural areas through community-driven development.

-

2.

Agricultural Partnerships: To strengthen the linkages between smallholder farming households and markets through agriculture partnerships and support.

To date, the RDP has provided funding and technical support to implement more than 1636 projects, activities, and partnerships impacting more than 337,162 Solomon Islanders in rural communities across the country. The program is designed to ensure the inclusion and participation of all community members, with a specific emphasis on women, youth, and people with disabilities. RDP is a government initiative co-funded by the World Bank, Australian Government, European Union, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development.

10.3.2 Community and Infrastructure Services

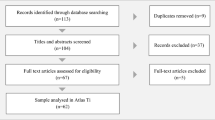

RDP supports rural communities to identify, design, and operate their own projects and services. The program builds on existing community resources and capacities and provides training, material, technical, and administrative support to enable communities to complete, operate, and ultimately maintain their chosen projects. Communities are supported in organizing representative village level committees to manage the project, which enhances community ownership and skill development. Additionally, communities contribute a minimum of 15% of the resources (often in the form of gravel, sand, and timber) for a project. To date nearly 500 community projects have been completed across every province in Solomon Islands, with over 200 more projects completed by 2020. Completed community projects by sector is shown in Fig. 10.8.

Community projects by sector (http://sirdp.org.sb/stories/community-infrastructure-services/)

10.3.3 Water Security in Radesifolamae Village, Malaita Province

In 2016, Radesifolamae water crisis finally came to an end when the Solomon Islands Rural Development Program (RDP) funded the construction of a new water supply scheme. In previous years, four children in the village had died. Two from falling into the village’s ground well, and two more from diarrhea caused by unknowingly drinking from the well after it had been contaminated. Today, every household enjoys easy access to clean water, as a rain catchment system now feeds 20 water tanks shared across the 60 homes in the community. In addition to preventing further tragedies, the proximity of a clean water source has dramatically improved day-to-day life for residents of Radesifolamae.

Mothers , or more often their children, previously traveled 45 min by canoe to collect water. The 90-min roundtrip gave families a difficult choice to make. Either parents would have to take time away from crafting shell money—the primary source of income for Radesifolamae residents—or the kids would have to skip school to fetch water for the family. Selimina, a mother of two, acknowledged the stark reality she was faced with. “If you don’t have time to make shell money here, there’s no way you can survive,” she shared. Selimina’s children frequently missed school, as they were tasked with fetching water while she made shell money to support the family. When Selimina instead fetched the water herself so her kids could attend school, her income dropped. It was a precarious position to be in, and one that she is relieved to no longer face.

The security that comes with access to clean water has improved the livelihoods of all 102 families in Radesifolamae. With more time to make shell money and less stress over water, mothers are earning more money for their families. Selimina revealed that her monthly income has increased from SI$500 to SI$1000 per month. Crucially, her children now attend school every day, and village leaders reported that nearly every child attends school on a daily basis. The new water supply has enhanced income and livelihood development and has inspired hope among Radesifolamae residents for continued growth in the future.

10.3.4 Improving Livelihoods Through Access to Clean Water, Komubeti and Gilutae, Guadalcanal Province

KOMUBETI and Gilutae are two rural communities nestled in the plains of Guadalcanal. With fertile soil primed for fruit trees and vegetable gardens, village members subsist primarily on the food they grow on their land. Now with the support of the Solomon Islands Rural Development Program (RDP), they also enjoy an essential human right: access to clean water. RDP facilitated the installation of boreholes and pumps to fill gravity water tanks in Komubeti and Gilutae in 2014, after flash floods had decimated the two villages. The floods washed away homes and gardens and also contaminated the hand-dug wells which previously provided the only source of water. Many children suffered from dysentery and diarrhea in the aftermath of the floods, and the time spent caring for ailing children and bringing them to and from the clinic took parents away from repairing their homes and gardens.

Additionally, villagers faced the challenge of needing to walk as long as 45 min each way to fetch clean water. Such extensive time spent collecting water everyday limited the villages’ economic productivity. Today, nearly 50 families in the villages enjoy the benefits of the new water system, with water tanks perched high above ground and safe from contamination delivering clean water to every home. The project’s impact on the community has been immediately felt. In Gilutae, Elizabeth captured the profound freedom that a clean and consistent water source has provided for her village.

“Our schedules don’t have to revolve around water anymore. We can work in our gardens, take care of our children, even go fishing late at night, and we don’t have to worry about having water when we get home.” No cases of diarrhea or dysentery have been reported since the completion of the project, and community members also benefit from the time saved by no longer walking far distances to fetch water. The Rural Development Program has brought potable water to over 200 communities across Solomon Islands. Some data from the Komubeti and Gilutae villages are shown in Table 10.2.

10.4 Solomon Islands Preparation Towards Achieving SDG Targets (2016–2030) in Clean Water and Sanitation

Solomon Islands has prepared several policies in facing the 2016–2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through The National Development Strategy (NDS) 2016–2035. The Solomon Islands National Development Strategy establishes a vision for the developmet of socio-economic by focusing on creating the change and livelihood environment, the vision is “Improving the Social and Economic Livelihoods of all Solomon Islanders.” To support the vision, the Solomon Islands government set a national mission “to create a peaceful, harmonious and progressive Solomon Islands led by ethical, accountable, respected, and credible leadership that enhances and protects peoples’ culture, social, economic, and spiritual well-being.” This highlights on a direction focused on creating a Solomon Islands that is enriched in its diversity, united, peaceful and stable and led to progression by credible and accountable leadership. Several planning objectives in the NDS are aligned with the SGDs, including water and sanitation which are included in the objective number 2: Poverty Alleviated across the whole of Solomon Islands, basic needs addressed and food security improved; benefits of development more equitably distributed (Solomon Island Government, 2020).

Solomon Islands tries to achieve the global target of SDGs in the field of clean water and sanitation by setting a national target of 60% of the population being able to access safe drinking water by year 2035, this target is inline with the global target 6.1 to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all by 2030. Meanwhile, for the national sanitation sector, the Solomon Islands target is the same as the global target 6.2 to achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations. To acchieve the SDGs target 6.1 and 6.2, Solomon Islands developed the Medium Term Strategy (MTS) 2016–2020 by build and upgrade physical infrastructure and utilities with an emphasis on access to productive resources and markets and to ensure all Solomon Islanders have access to essential services (MTS 3), and MTS 5, alleviate poverty, improve provision of basic needs and increase food security (Solomon Island Government, 2020).

To speed up the water and sanitation service in rural areas Solomon Islands Government came up with the Rural Development Program (RDP), an initiative co-funded by the World Bank, Australian Government, European Union, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development. It has reached over 50% of Solomon Islands’ population and operates in all 9 provinces and 172 wards of the country, from the atoll of Ontong Java to the north, Rennell and Bellona to the south, Anuta and Te Kopia to the East and Shortlands to the west (Rural Development Program-Solomon Island, 2020). The purpose of RDP is divided into two categories: (1) Community Infrastructure and Services: To improve basic infrastructure and services in rural areas through community-driven development (RDP-1) and (2) Agricultural Partnerships: To strengthen the linkages between smallholder farming households and markets through agriculture partnerships and support (RDP-2). Both of these categories can be seen in Fig. 10.9 with the distribution of water project locations.

Distribution of rural water project location in Solomon Island (Rural Development Program-Solomon Island, 2020). *RDP = Rural Development Program

The Solomon Islands Government through the Ministry of Development Planning and Aid Coordination is serious to combat the low level of water service in the rural area with the Rural Development Program. This program is participatory program, which the rural community will send the request to the government for the project and manage the project by management and supervision from the RDP team. The number of projects increased and covered most of the provinces in Solomon Islands.

The RDP sanitation project in Solomon Islands as shown in Fig. 10.10 which is referring to RDP-1 is for the community infrastructure and services. Basically, RDP-1 is to improve the basic infrastructure and services in rural areas through community-driven development.

Distribution of sanitation project location in Solomon Island (Rural Development Program-Solomon Island, 2020). *RDP = Rural Development Program

There are six (6) targets for clean water and sanitation which still yet to be covered in Solomon Islands National Development Strategy are (a) Target 6.3 Improve Water Quality, Wastewater Treatment And Safe Reuse\Improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse global by 2030; (b) Target 6.4: Increase Water-Use Efficiency And Ensure Freshwater Supplies. By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity; (c) Target 6.5: Implement Integrated Water Resources Management. By 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate; (d) Target 6.6: Protect and Restore Water-Related Ecosystems. By 2020, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers, and lakes. (e) Target 6.A: Expand Water and Sanitation Support to Developing Countries. By 2030, expand international cooperation and capacity building support to developing countries in water- and sanitation-related activities and programs, including water harvesting, desalination, water efficiency, wastewater treatment, recycling, and reuse technologies; (f) Target 6.B: Support Local Engagement in Water and Sanitation Management. Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management (The Global Goals, 2017).

In order to support the achievement for all the SDGs target 6, which is the Clean Water and Sanitation, Solomon Islands have prepared the National Water Resource and Sanitary (WATSAN) Policy in 2017 (2017a) and WATSAN Implementation Plan 2017–2033 (2017b). The purpose of the WATSAN policy is: to provide the government leadership in the vital water and sanitation sectors and to improve the development opportunities, the health and well-being of all Solomon Islanders; protect the source of water and receiving environment; respond to widespread rural and urban concern about the safety, adequacy, and reliability of water supply and sanitation service; identify the national priority areas and issues which require government and donor intervention in the WATSAN sector, built the WATSAN goals in the NDS and give a clear policy goals and objectives; signal Solomon Islands’ priorities in water and sanitation; provide the strategy for adapting to global changes and provide the mechanism for monitoring policy outcomes and reviews (Solomon Islands National Water And Sanitation Implementation Plan, 2017a).

Meanwhile the National Water and Sanitation Implementation Plan is a 12-year integrated whole-of-government plan to implement the goals and objectives of the Solomon Islands National Water and Sanitation Policy (National WATSAN Policy), the sector goals of the National Development Strategy 2016-35 (NDS). It is consistent with other Government initiatives and strategies, including the Draft Rural Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (RWASH) Policy, National Adaptation Plan of Action, 2009, Draft Medium Term Development Plan, 2013, Solomon Water (SIWA) Development Plan 2013–2015, National Disaster Risk Management Plan 2011, and the water and sanitation sector component of the Draft National Infrastructure Investment Plan 2013 (NIIP) (Solomon Islands National Water and Sanitation Implementation Plan, 2017a).

Some plans that Solomon Islands prepare in order to achieve SDGs target 6 for Clean Water and Sanitation are listed below:

-

1.

Preparing the plans, guidelines, and regulation ordinance for the water resources, water supply, hydropower, and sanitation in urban and rural areas.

-

2.

Skill training program for water and sanitation managers, technical staff, and community operators.

-

3.

Adding the education curricula on water and sanitation, waste management, and hygiene improvement in all levels of education.

-

4.

Public education and campaign awareness in urban and rural area related to good quality water, conservation, water source protection, adequate sanitation, and hygiene.

-

5.

Improve and reliable access to customary-owned public water source.

-

6.

Increase use of household and community rainwater harvesting by preparing the standards and building codes, training for installation, operation, and maintenance.

-

7.

Community participation in non-urban and rural area for water supply system.

-

8.

Increase the use of renewable energy and hydropower generation.

-

9.

Reduce less than 20% of losses water from the pipe by decreasing the illegal connection.

-

10.

Fair, equitable, tiered-water tariff introduced for all urban piped water system to control growth in demand and discourage wastewater.

-

11.

Train the rural communities to use and maintenance of sanitation facilities and hygiene.

-

12.

Sewerage outfalls and waste disposal sites in all urban centers to minimize off-site pollution.

-

13.

Water supply and sanitation system at risk from sea level rise and storm surge; and.

-

14.

Improved urban and peri-urban drainage.

10.5 Water and Sanitation Governance and Access Improvement Progress

10.5.1 Objectives and Purpose of “RWASH” Program in Solomon Islands

The Government of Solomon Islands signed, on 24th July 2014, a Financing Agreement for €17.4 million with the European Union for “improving governance and access to water, sanitation and hygiene promotion (WASH) for rural people.”

This resulted in a rural WASH Program now known as “RWASH.” The RWASH Program has the following objective:

“To support implementation of the sector policy for the Program of Improving Governance and Access to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion for Rural People.”

The purposes of the contract are:

-

1.

To enable a healthier and safer environment in households, schools, and clinics, particularly for women and children, reducing the impact of water borne diseases and hygiene related illnesses in rural communities and

-

2.

To improve governance and quality of service delivery in the Rural WASH sector in the context of climate change.

10.5.1.1 Policy Context

The national policy context is relatively clear and shows a documented commitment to increasing WASH coverage to the point where nearly all Solomon Islanders have reasonable access to water and sanitation services by 2024. The current National Development Strategy (NDS) for the period from 2016 to 2035 states that during the consultations conducted with Provincial stakeholders, water and sanitation were raised as being of the highest priority in rural areas. The NDS includes the objective of providing access to water for all Solomon Islanders by 2030.

The National Health Strategic Plan (NHSP) 2016 to 2020 echoes the NDS and sets access to water, sanitation, and health and hygiene as a priority. This includes a focus on communities and health facilities and recognizes the impact that access to clean water and safe sanitation has on overall community and national health.

The WASH Strategic Plan 2015 to 2019 has set very high targets for improving access to water, sanitation, and hygiene services and includes both 5-year and 10-year targets. It is apparent now that the water target for 2019 was set too low and has been achieved with very little actual progress in coverage. All three of the targets are extremely ambitious for 2024 (Table 10.3).

10.5.1.2 Improving Health Through Community Participation in RWASH Project in Solomon Islands

Published by the National Newspaper on the second of August 2015, Mr. Charley Piringi reported that the Ministry of Health Officials led by the Research and Training Officer, Mr. Leonard Olivera together with the Solomon Water (SIWA) officers who undertook training in Australia under the title “Improving Health through Community Participation in RWASH Projects in Solomon Islands.” The team undertook a month-long training under the Australia Awards Fellowships (AAF 15) Program in Brisbane at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) and presented their “Action Plan” to the Environmental Health Department. In the presentation, Mr. Oliver said their Action Plan, “The AAF 15 Rural water Supply Sanitation and Hygiene Integrated Strategy Action Plan, RWASH-ISAP aims to improve governance, enhance policy development and implementation, strengthen data collection, information management, and communication, identify appropriate methods and techniques for water treatments, indicate culturally applicable and cost-effective measures to improve hygiene, and to guide professional and technical capacity building.”

Environmental health director at that time, Mr. Nanau, said the report was timely and inclusive. “He commends the team for their job well done. There will be a budget for this report, and its implementation.” WASH project is a partnership between the Solomon Islands Ministry of Health and Medical Services (MHMS) and The Solomon Water (SIWA) together with the Queensland University of Technology.

10.5.1.3 The RWASH Integrated Strategic Action Plan

The RWASH program is a rural innovative program of the Solomon Islands initially known as the rural water supply and sanitation program. Currently the program is supported by DAFT, the European Union, and the Solomon Islands Government. As stipulated in its policy and national strategic plan, the vision is to enable all Solomon Islanders to have access to sufficient quantity of water, appropriate sanitation as well as living in a safe and hygienic environment. Located in the Ministry of Health and Medical Services, the program aims to achieve this goal by 2024.

The training that was held in Australia has exposed the participants to an intensive learning and interactions with the Queensland University of Technology (QUT), water experts and firms (Seqwater), site visits and study tours to communities in the Far North Queensland (FNQ) in the remote communities of Yarrabah and Hope Vale and introduced to their community water treatment systems. Before returning to the Solomon Islands the final week of the program an Integrated Strategic Action Plan known as a Return-to-Work Action Plan (RTWAP) was developed for participants to implement on their return to Solomon Islands.

While the action plan will serve as a blueprint of the actions to be done, this report is based on the actual encounters while in the process of implementing the action plan. Overall, the award has given the participants some broader views of the RWASH program and the confidence to contribute more effectively to ongoing program in the Solomon Islands. The RWASH Integrated Strategic Action Plan was aimed at making contributions to improve governance, policy, information, communication, methods and techniques and capacity that can be used by RWASH partners to deliver measurable health improvements in rural areas of Solomon Islands. Five broad objectives were identified with strategies to be implemented within certain timeframe as can be sighted in the AAF15 Rural Water Sanitation and Hygiene Integrated Strategic Action Plan which serves as the Return-to-Work Action Plan document. This paper therefore serves to provide an up-to-date report on the performance, achievements, and recommended actions in the way forward towards realizing the objectives of the action plan.

10.5.1.4 Governance

Regarding the objectives of governance objectives, two broad approaches were developed focusing on program leadership and work plan development and approval. Upon return from the AAF 15 training program in Australia, efforts were taken to improve dialogue between all stakeholders, including the hierarchy of the RWASH sector, the urban water authority and aid partners by disseminating the outcome of the program and where possible develop strategies to be incorporated into the annual departmental operational plans and work activities. The following activities were undertaken to ensure the strategies are implemented as summarized below (Table 10.4).

10.5.1.5 Ability to Share Knowledge (Corporate Intelligence)

Two key strategies were designed under this objective to be achieved through the development of the RWASH Resource and Information Centre and through data sharing system and protocols.

-

1.

RWASH Resource and Information Centre: Development of the RWASH Resource and Information Centre is an ongoing departmental activity and involves the development of a resource and information center for RWASH including environmental health. Activities included infrastructure development components: a room, shelves, tables, chairs and computers, printers and the software components to include books and e-library. Activities namely: (1) Production of RWASH IEC materials and printing completed; (2) Installation of internet facilities also completed; (3) Continue ordering of books and development of Resource Materials which already completed and lastly the promotion of the facility which is still ongoing.

-

2.

Data Sharing System and Protocols: A Community Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) National Survey was conducted to come up with a baseline on RWASH in the Country. The objectives of the community WASH baseline as stated in the plan document are to provide an:

-

(a)

Understanding of the national coverage on WASH baseline; are services available? (schools, clinics and villages).

-

(b)

Understanding of the level of access to WASH including operation/functionality/water quality (can people get to or use the services?)

-

(c)

Initial assessment of governance structures in place at the moment for comparison in the future (what support is in place for the services?)

The initiative was jointly supported by Water Aid and UNICEF and currently survey was completed awaiting analysis and compilation of data for publication. It is also anticipated that provinces will be involved in the process through a series of workshops to fully understand the process and the outcome of data survey, analysis, and uses.

-

(a)

10.5.1.6 Evidence to Ensure New Policies and Programs Is Successful (Evidence for the Rural Water Safety Plan)

The national campaign program for schools’ handwashing in the Solomon Islands was launched last year. It started as a trial for 14 schools in Guadalcanal province and Honiara City Council. Activities completed to date were the baseline survey of the 14 schools and now in the process of data analysis. Out of the findings, a detailed strategy for activities will be drawn up and scheduled for implementation this year. The objectives of the program are to position handwashing as a valued behavior and social norm; to support increased adoption of health protective behaviors such as handwashing at key times, support children to become agents of change in relation to wash in schools and communities, finally build a foundation for future C4D initiatives on aligned themes.

Other activities

-

1.

Presentations of survey findings and working with all stakeholders to come up with strategy for the campaign.

-

2.

Production of IEC materials.

-

3.

Running of handwashing campaign in schools.

10.6 Achievements in the WATSAN Sector in Solomon Islands from 2016 to 2020

According to Fig. 10.11, the results show that the percentage of achievements have been maintained at a consistent level. The graph illustrates that there is a high achievement of drinking water improvement for urban area and above 50% for the rural areas. In 2020, nationally, the population using an improved drinking water was at 73%.

Proportion of Solomon Islands’ population using an improved drinking water 2016–2020 (WHO/UNICEF JMP, 2021)

Unfortunately, as for Sanitation, it does not go in line with drinking water improvement. Based on Fig. 10.12, though the Urban Sector shows a consistent improvement of 95% achievement, but for the rural area achievement, the achievement is still under the target of SDGs 6.

Proportion of Solomon Islands’ population using an improved sanitation 2016–2020 (WHO/UNICEF JMP, 2021)

Table 10.5 shows the improvement water service level in Solomon Island in 2016 and 2020, at the national level the improved water decline from 2016 (74.3%) to 73.1% in 2020. Conversely, the improved water service in the urban areas increases slightly by 0.1% from 2016 to 2020. As for the rural area, a decrease of 2.3% from 2016 to 2020.

Basically Table 10.6 is towards the urban area. Most of the urban areas are more easily accessed by land transport in which the rural area has difficulty with the access of sea transport. Though the table above shows some improvements in the urban setting, rural setting is still decreasing which is not an encouraging result but an indication of more focus should be towards the rural setting.

According to Table 10.7, the improved sanitation service in Solomon Island increases from 38.2% from 2016 to 40.6% in 2020 Nationally. However, the table shows no unimproved sanitation and more should be focussed with the rural setting having the case of unimproved sanitation increases by 4.3% from 2016 to 2020 which should not happen.

The proportion of the population using the septic tank as improved sanitation was increased at the national level from 18.5% in 2016 to 20.2% in 2020, but this condition was not applicable in an urban area, as per data in Table 10.8 shows that the proportion of the population using the septic tank declines from 52.7% in 2000 to 43.2% in 2015. The decline in population proportion in urban areas, who using septic tanks may have caused by using the latrines which increased 28% in 15 years. The data in Table 10.8 also indicate that Solomon Islands Water Authority (SIWA) not yet improve the sewer connection to the new development area.

10.7 Key Constraints

In addition to current targets being high and unattainable within the existing capacity and funding context, there is some uncertainty due to the use of communities and villages when calculating the coverage nationally rather than just using percentage of the total population. The existing WASH Strategic Plan includes targets for how many systems should be constructed both in community wash and for health facilities and schools; however, it is unclear what size these schemes are and what impact they would have on national coverage. While there are 1200 schools and only 346 clinics the target numbers for facilities to be constructed in schools and clinics are the same.

The move by the Ministry of Health and Medical Services (MHMS) to adopt indicators that are closer to global indicators was a good one, but as part of it one of the indictors was changed from the number of communities who are open defecation free, to the percentage of population using basic or safely managed sanitation services. This has caused some confusion given that the starting point for open defecation free communities was 0%, and the starting point for sanitation closer to 14%. Currently, there is little other work going on in the sanitation sector and so any improvements in sanitation coverage will be a product of success in ongoing and future Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS).

While the WASH Strategic Plan appears sensible and encourages a move to a more regulatory function for the RWASH unit, it has not been implemented as intended. There is some disagreement among key stakeholders concerning the strategy and how quickly construction should be outsourced to others rather than completed by the Environmental Health Divisions (EHD) of each province.

Given the current capacity within the Solomon Islands to implement wash activities, particularly in some of the smaller provinces, it would be quite difficult to make significant progress if the provincial environmental health divisions were not doing construction. The strategy suggests that provincial Environmental Health Divisions oversee service delivery partners to monitor their work and ensure they maintain up to date information. However, in some provinces, it has only been the Environmental Health Division who has constructed water supply systems over the past 20 years.

So, while there is not necessarily a reluctance to contract out construction, the structure of provincial divisions is still one that has been developed to do construction rather than monitoring and supervision.

The adoption of CLTS as the only strategy to increase sanitation coverage does not appear to be fully supported at the national level within the EHD. Certainly, the concept of zero subsidy is not fully supported and some senior officers would prefer to have at least a small or smart subsidy, perhaps one that is paid after successful construction of a toilet.

While the strategy includes schools and health facilities as part of the WASH program, it does not include percentage coverage targets and there is little information about current status of clinics. This lack of information and shortage of funds have meant that there has been little done to develop a meaningful implementation plan to increase coverage on schools and clinics, although hopefully new information that is currently being gathered by UNICEF will allow a more strategy approach to be adopted.

Operating in the Solomon Islands across all nine provinces is a complex and logistical challenge. Communications are still poor and internet across often lacking or of poor quality. This coupled with the lack of a clear implementation plan with associated key responsibilities, activities, and dates makes it difficult to operate effectively and contribute to the very slow pace of progress in achieving WASH targets.

There is a range of operational constraints on the RWASH Program. Procurement of both goods and services follows government systems and lengthy approval processes can cause delays to activities. Funding for travel and touring allowances is difficult to secure and can take so long that the planned activities have had to be cancelled.

Procuring materials for construction of projects can be a slow process, and once materials are procured the delivery, storage, and subsequent freighting to project sites are all opportunities for both fraud and delay. Past fraud has made it more difficult to procure and ship materials with increased scrutiny and caution contributing to delays.

The current practice of ad-hoc procurement is not effective and means that the project is always trying to make things happen, but without an agreed plan or timeframe. This makes it difficult to achieve value for money in both the procurement of materials and the shipping of them around the country. Possibly the biggest operational constraint now is the lack of agreement on how the program should be implemented, in terms of doing construction or contracting others to do construction. This has led to a decrease in productivity and increased delays that reflect the differing opinions within the EHD and RWASH Program.

10.7.1 Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E)

Considerable effort has been made over the last 2–3 years to develop an effective M&E system. This system has made some attempts to quantify the current situation in terms of WASH coverage and to monitor the number of projects that are being constructed. This is an improvement on what existed before but there is still a need to improve the systems for monitoring particularly at the national target level, M&E efforts are focused on developing systems for monitoring the WASH Strategy; however, as outlined above, the WASH Strategy has as its main focus the numbers of projects constructed and includes references to communities and villages rather than % of population.

10.7.2 Funding

There are a number of key constraints holding the WASH sector back. While funding is not a constraint in the very short term, it certainly is in the 2019 to 2025 period. Slow spending of current EU funds has slowed the increase in WASH coverage, but more importantly it has created the misconception that there is sufficient funding in the sector. The RWASH Program currently has targets in the community, schools, and clinics WASH sectors. For significant progress to be made in all of these sectors, significant additional funding will be needed.

10.8 Conclusion

Attempts to get the AAF 15, RWASH Integrated Strategic Action Plan implemented have met certain challenges especially as from the hierarchy of responsibilities in RWASH more often with differing interests and meanings as to what the program is all about. The key challenge in the program will always to be to ensure delivery of safe quality water, sanitation, and hygiene that are sustainable and accessible to ensure health and well-being of Solomon Islanders. While this is a vested responsibility of all partners involved in the RWASH sectors, the onus will always be on Solomon Islanders that is why our participation in the AAF must be always seen as crucial and recommendations must be implemented. While to some extended, awareness on the AAF R15 RWASH was well undertaken, we are expected to do more this year to eventually get the policies and trials implemented as they are steppingstone in the way forward.

Equal emphasis needs to be focus on micro planning especially in strengthening mechanisms for provinces in terms of organizational capacity to better communicate and work with communities. Likewise, communities need to be supported too in terms of capacity building to effectively make decisions and manage completed RWASH Projects. The role of monitoring and evaluation of projects therefore is an important component of partnership support to the RWASH program.

The current Australian Government support to RWASH is on improved access to and use of sanitation facilities and hygiene practices in every rural household and community. This is intended to be achieved by the following strategies: no subsidy funding, creating a demand for sanitation; CLTS will be rolled across the country so that individuals will build and use toilets themselves, hygiene communication focusing on people washing their hands with soap at critical times and sanitation marketing by ensuring supply chain is there to support the process.

The roles of the communities must be well established through communicated mechanisms to support these strategies. This would seem a far reached goal, we could assume but the greatest assurance of success on this comes if communities are fully supported in terms of capacity building to RWASH community-based organizations and improved monitoring by provincial RWASH.

Solomon Islands has prepared several policies in facing the 2016–2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through The National Development Strategy (NDS) 2016–2035. The Solomon Islands National Development Strategy establishes a vision for the developmet of socio-economic by focusing on creating the change and livelihods environment, the vision is “Improving the Social and Economic Livelihoods of all Solomon Islanders.” To achieve the SDGs target 6.1 and 6.2, Solomon Islands developed the Medium Term Strategy (MTS) 2016–2020 by build and upgrade physical infrastructure and utilities with an emphasis on access to productive resources and markets, and to ensure all Solomon Islanders have access to essential services (MTS 3), and MTS 5, alleviate poverty, improve provision of basic needs, and increase food security.

According to the RWASH Strategic 2019 targets for rural areas indicated the access to an improved drinking water target to be 52%; however, 65.9% was achieved already in 2018 and remained the same till 2020. Nationally, the achievement was 73.1% (2020) compared to 74.3% in 2016. The urban improved drinking water coverage was 95% throughout 2016–2020. Unfortunately, the 2019 open defecation free target for rural areas was 87% (13% practicing), but in 2020 still 58% was practicing open defecation in the rural. This was only 1% improvement from 2016 (59%).

In addition to current targets being high and unattainable within the existing capacity and funding context, there is some uncertainty due to the use of communities and villages when calculating the coverage nationally rather than just using percentage of the total population.

References

AusAid-QUT (2015) AAF ROUND 15; Improving Health through Community Participation in RWASH Project in Solomon Islands (Progress Report). (n.d.). RWASH PROGRAM, ENVIRONMENTAL DIVISION, MINISTRY OF HEALTH & MEDICAL SERVICES, P.O.BOX 349, HONIARA, SOLOMON ISLANDS.

Hunterh2o (2017) 30 Year Strategic Plan Solomon Water. Honiara. Available at: https://www.solomonwater.com.sb/files/docs/strategic-plan/30YearStrategicPlan-MainReport.pdf.

Ken, M. (2018). Technical Assitance to the Program of Improving Governance and Access to Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Promotion (WASH) for Rural People. Ministry of Health and Medical Services. Office of the National Authorising Officer, MDPAC.

Mishra, S., Hargreaves, k, Moretto, A. (2010) Millennium Development Goals Progress Report For Solomon Islands 2010. Honiara Available at: http://prdrse4all.spc.int/system/files/final_si_mdg.pdf.

Pacific Island Forum Secretariat (2015) Pacific Regional MDGs Tracking Report 2015. Suva Available at: https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2015-Pacific-Regional-MDGs-Tracking-Report.pdf.

Pacific, W.H.O.R.O. for the W. (2016). Sanitation, drinking-water and health in Pacific island countries: 2015 update and future outlook. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific[online] iris.wpro.who.int. Available at: https://iris.wpro.who.int/handle/10665.1/13130.

Rural Development Program-Solomon Island (2020) Rural Water Project at Glance in Solomon Island. Available at: http://www.sirdp.org.sb/. (Accessed 1 June 2021).

Schrecongost, A. et al. (2015) Unsettled : Water and Sanitation in Urban Settlement Communities of the Pacific. Sydney: Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/603081468197054598/pdf/101065-WP-v2-PUBLIC-Box393257B-full-report.pdf.

Solomon Island Government (2020) ‘Solomon Islands Voluntary National Review’, (June), p. 105.

Solomon Islands National Water and Sanitation Implementation Plan (2017a) National Intersectoral Water Coordination Committee Ministry of Mines, Energy And Rural Electrification. . [online]. Available at: https://www.theprif.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/Soloman%20Islands%20WATSAN%20Implementation%20Plan.pdf.

Solomon Islands National Water and Sanitation Implementation Plan (2017b) Solomon Islands National Water and Sanitation Implementation Plan 2017–2033. Pacific Regional Infrastructure Facility (PRIF). [online] Available at: https://www.theprif.org/document/solomon-islands/water-wastewater-and-sanitation-country-development-strategiesplans [Accessed 15 Jul. 2021].

SPREP (2019) Solomon Islands State of Environment Report 2019. Apia. Available at: https://www.sprep.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/soe-solomon-islands-2019.pdf?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=6a30d01ab3f0f42b9bd54063c0689051edda4392-1622422452-0-AZogRpUN74tIVgXkd6PHAvcVknyrRK_shwyHdkKE7Yl4Mu6HUuI9reZupYskYF_GorBzv5IeFk-hZJHe4_WdL5B.

The Global Goals. (2017). Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation. [online] Available at: https://www.globalgoals.org/6-clean-water-and-sanitation.

WHO, UNICEF and JMP (2019). Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene. Estimates on the use of water, sanitation and hygiene in Solomon Islands.

WHO, UNICEF and JMP (2021). Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene. Estimates on the use of water, sanitation and hygiene in Solomon Islands.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support we received from the Australia Awards Fellowships Program (AAF 15) through Queensland University of Technology that paved the way for continued dialogue and interactions in advancing the objectives of the AAF 15 Integrated Action Plan implementation. If not come quickly but sure it will come by the years, like a seed planted and nurtured one day grow and give meaning to Solomon Islanders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rachman, C.B., Olivera, L., Qomariyah, Y. (2022). Readiness of Solomon Islands in Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Water and Sanitation. In: Rajapakse, J. (eds) Safe Water and Sanitation for a Healthier World. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94020-1_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94020-1_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-94019-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-94020-1

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)