Abstract

Inventions and improvements of advanced energy technologies—technologies that power active networks, that catalyze greater use of renewable resources, that improve energy efficiency, and that are developed synergistically with broad sustainability goals—are necessary to improve local, national, and global well-being. Indeed, all dimensions of ‘energy sustainability’—including the historically-overlooked issue of social acceptance—are critical. Events during 2020 highlighted further many elements of the contemporary sustainability agenda. Because energy is central to human existence and well-being, and because the sustainable provision of critical energy services will continue to be a key priority for communities in the future, those working in the energy sector must ensure that sustainability considerations are integrated into their work. This article offers perspectives and insights to guide this integration.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction and Purpose

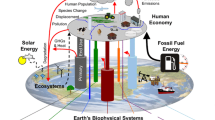

The purpose of this chapter is to investigate sustainability within the context of transformative energy systems. While inventions and improvements of advanced energy technologies—technologies that power active networks, that catalyze greater use of renewable resources, and that improve energy efficiency—are necessary to improve local, national, and global well-being, they are not, by themselves, sufficient. Instead, it must be ensured that such technological development takes place in ways that are synergistic with other parts of the broader social, economic, and environmental context. This chapter provides those focusing upon specific technological innovations with details of that broader context so that their actions can be designed to have greater impact; likewise, this chapter also equips those working within this broader context with an increased appreciation for how such connections can effectively be made.

The chapter is divided into seven main sections. Following this brief introduction, the following two sections introduce the concept of sustainability—initially in its broadest form, and then with a particular focus upon energy sustainability, providing some historical context and also outlining the current global agenda. The fourth section then looks at social acceptance issues associated with transformative energy systems, arguing that they were, until recently, a relatively oft-overlooked set of topics.

The fifth section briefly reviews the monumental events of 2020, focusing upon the global pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement, highlighting their impacts upon particular areas of concern for energy professionals and society more broadly. Material from this section—and indeed from all parts of the chapter—is then used, in the following section, to sketch out the contemporary sustainability agenda for those whose work serves to invent and/or to improve advanced energy technologies. A brief final section summarizes and concludes the chapter.

2 Sustainability

The term ‘sustainable development’ was widely popularized in the late 1980s, in the wake of the 1987 publication of the Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (commonly known as the Brundtland Report). Defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’, attention to the term increased the awareness of both spatial and temporal impacts of activities that served to advance economic growth [40].

During the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, sustainable development issues were addressed at various levels. At the international level, activities around a number of global mega-conferences served to advance the issue—namely, the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development (Johannesburg, South Africa), and the 2012 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). They focused global attention upon a range of challenges and opportunities that transcended environmental, social, and economic boundaries (let alone geographic boundaries), and they also served to be a location whereby individuals and institutions from around the world could work together to build systems of monitoring, evaluating, and potentially transforming. While many analysts give such summits mixed reviews, it is nevertheless the case that they provided unique universal opportunities for reflection and discussion [27, 43].

Also noteworthy at the global level during this period was the world’s activity to develop a set of universally-agreed ambitions for sustainable development. In 2000, 147 heads of state met at the United Nations Millennium Summit (New York City, United States) and agreed on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The MDGs consisted of specific targets for the year 2015 across eight areas (see Table 1). While some criticized the MDGs for being too narrowly focused and not sufficiently comprehensive, they nevertheless catalyzed many conversations around global targets, encouraged goal setting in global governance, and set the stage for the 2015 agreement of the Sustainable Development Goals, to which I return below [6, 41, 57].

Further to this global level activity on sustainable development during the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, much activity also occurred at national and local levels. And much of this was catalyzed by a particular emphasis upon implementation of global aspirations and commitments: this was initially prompted by the 1992 publication of Agenda 21 (at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, noted above), subsequently further stressed in the 2002 and 2012 conferences mentioned above. Nationally, several countries produced (and continue to produce) sustainable development strategies, which would not only be used domestically but would also often be fed into United Nations processes [1, 31]. And locally, ‘Local Agenda 21’ was a prominent vehicle for such discussions during the latter part of the twentieth century and the initial part of the twenty-first century; more recently, a variety of terms have been used to advance the same priorities, including sustainable cities, sustainable communities, and sustainable urbanization [5, 26].

While activity at all of these levels yielded some success—though not met entirely, the MDGs did much to address, in particular, global poverty [49]—it was clear that, by the middle of the 2010s, efforts to advance sustainability needed not only to continue but indeed needed to be accelerated. Annual reporting on the ‘emissions gap’ by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), for one, contributed to this sentiment. This emissions gap was calculated by finding the difference between two values: (i) the 2030 greenhouse gas emission levels needed to keep anticipated average global temperature increases by 2100 below 2 °C; and (ii) the 2030 greenhouse gas emission levels anticipated, given then-current national projections and plans. In 2015, for instance, the gap was calculated to be the difference between 42 GtCO2e (where emission levels needed to be in 2030 in order to ensure global climate stability) and 54 GtCO2e (a ‘best case scenario’, given then-current trajectories and plans; the baseline was closer to 65 GtCO2e). This gap of 12 GtCO2e was expected to have monumental socio-ecological impacts [47]. And UNEP was by no means alone in its assessment. The Stockholm Environment Institute’s work on planetary boundaries across nine critical processes, for instance, also served to reinforce the conclusion that the world’s efforts to advance sustainability were falling short [42].

Thus, on 5 September 2015, at the United Nations headquarters in New York City, United States, 193 countries agreed to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and—as part of that—17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Succeeding the Millennium Development Goals, the SDGs were accompanied by 169 targets, whith countries committed to implementing by 2030. In the half-decade since their introduction, the SDGs have come to be part of many discourses, being focal points for a range of governmental, business, and other organizations’ activities, plans, and aspirations. Their impact, moreover, appears set to continue to grow. The SDGs are listed in Table 2.

Finally, let me offer a note about terminology. I have used two terms throughout this section—namely, ‘sustainable development’ and ‘sustainability’. There have been several investigations into which term is most appropriate given any particular purpose that has been identified—([32], 6), for instance, draws upon earlier work, arguing that ‘while “sustainability” refers to a state, [sustainable development] refers to the process for achieving this state’. While such discussions are indeed worthwhile, they are beyond the scope of this chapter. Indeed, in this chapter, I follow much of the more recent literature (e.g., [19]) by primarily using the term ‘sustainability’.

3 Energy Sustainability

Unlike the earlier Millennium Development Goals—which did not have energy as a focus for any of its eight goals (see Table 1)—energy is prominent in one of the Sustainable Development Goals (see Table 2). More specifically, SDG7 is concerned with ‘committing to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all’. Full details of it and its associated targets and indicators are provided in Table 3.

In addition to the focus upon energy in SDG7, energy issues were also ‘part of’ many of the other 16 SDGs. Indeed, the attention drawn to such cross-connections was not least of all an effort to address one of the perceived failings of the MDGs—namely, their narrow focus; their ‘siloing’. Thus, while each of the SDGs has a particular focus (see Table 2), that does not mean that how that particular goal contributes to, or obstructs, progress on the other goals should be ignored. Instead, many argued, such connections—some of which could well be unanticipated and/or unintended—should be thoroughly investigated. For energy project proponents—and energy transition advocates—that means considering the impact of energy initiatives upon the other 16 SDGs (and also being cognizant as to how initiatives advanced under other banners—‘oceans’, ‘equality’, etc.—affect progress towards SDG7). These connections have been theorized and operationalized in a variety of ways (e.g., [29, 35]).

While not explicitly connected with the Sustainable Development Goals (for that term only entered the debate explicitly in 2015), how analysts have been connecting energy issues and sustainability issues date back decades. Indeed, Lovins’s call—in the wake of the first so-called energy crises of the 1970s—for a move to a ‘soft energy path’ (emphasizing energy efficiency), away from a ‘hard energy path’ (activities and policies that privileged fossil-based, centralized, supply-prioritized energy systems) is a prime early example [28]. Foci through the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s included sustainability issues with an economic emphasis (for instance, re-regulation for efficiency in energy markets) and sustainability issues with an environmental emphasis (for instance, reduction of polluting air emissions to ameliorate both local smog and global climate change). Reviews of this period can be found in, for example, [16], [53], and [54].

Today, discussions around the movement towards energy sustainability continue. Indeed, major energy-focused organizations have their proposals—or scenarios—associated with this transition. The International Energy Agency presents a number of scenarios in its flagship World Energy Outlook report, including different sustainable development scenarios [23]. The World Energy Council, for its part, emphasizes energy security, energy equity, and environmental sustainability of energy systems [58]. Other intergovernmental institutions that have a broader remit also have energy high on their respective agendas—for instance, the United Nations Development Program [45, 46] and the World Bank [64]. Business-based international organizations—like the World Economic Forum—have also advanced their particular perspectives on energy sustainability [59].

If the above can be called ‘mainstream’ global perspectives, alternative perspectives—often calling for a faster transition that is less reliant upon conventional market forces—are also being advanced. For instance, plans for more rapid decarbonization, explicitly accompanied by economic justice goals, have been put forward by [13]. By contrast, prioritization of renewable resources characterizes the work of the aptly-named International Renewable Energy Agency [25].

Finally, in addition to these international-level perspectives, there have also been debates at the national and sub-national levels—for example, Germany’s discussions around its energy transition (Energiewende) [38] and the work of the C40 [10], respectively.

To summarize this section of the chapter, note that there is an agenda focused upon energy sustainability. Having evolved over the past five decades, it—like sustainability more broadly—was originally fractured into its constituent economic, environmental, and social components. Encouraged not least of all by the emergence of the SDGs in 2015, however, recent investigations have been much more comprehensive and interconnected (and, as the next section will argue, have brought social considerations into greater focus). [11] document this by presenting a detailed literature review of sustainability evaluation for energy systems (2007–2017), as well as an associated database that can be used by energy professionals. And, to cite a specific example of such investigations, [12] advance the Sustainable Development Goals Impact Assessment Framework for Energy Projects (SDGs-IAE) and apply it to power generation projects in Ethiopia and the United Kingdom. Indeed, energy sustainability is the focus of an active, important, and rich set of discussions today.

4 Integrating Social Dimensions

As noted above, of the different constituent dimensions of sustainability, it is the economic and environmental elements that received the majority of the early attention; indeed, ([9], 1) reported that ‘the social pillar [of sustainable development] has earned a reputation for elusiveness, and even chaos in part because social priorities are diverse and context specific’. In this section, I consider the concept of ‘social acceptance’ of transformative energy systems.

Experience with the siting of energy projects, particularly nuclear power stations and wind-farms, has revealed that citizen acceptance of a project is critical to the success of the same project. More recent experience with the ‘user-end of energy systems’—in particular, programs like time-of-use tariffs and demand response incentives—has further demonstrated that acceptance can involve not only technology that is ‘much closer to home’ (e.g., solar panels on one’s rooftop), but also energy control procedures that though ‘technically invisible’ (e.g., an external signal that raises an air conditioning system’s set point by two degrees Celsius) may be viewed as intrusive by some. Without acceptance of such technologies and programs, transformative energy initiatives can ‘come off the rails’, even at advanced stages of development. In response, investigations as to how citizen acceptance can develop and be sustained have been undertaken.

Ground-breaking literature examining social acceptance of energy technologies and energy programs distinguished among multiple dimensions of social acceptance, most commonly: communities, markets, and socio-political dimensions [65]. More recently, increasing attention to the role of multiple actors has supplemented this traditional framework with the following foci: public acceptance, key stakeholder acceptance, and political acceptance [52]. Together, approaches like these have catalyzed many empirical studies that have served not only to refine these conceptual ideas but also to extend the range of energy technologies and energy programs investigated from an acceptance perspective.

Key recent investigations include the following: [15] propose a research agenda regarding the social acceptance of energy storage technologies, [17] examine elite-level attitudes towards energy storage in Ontario, Canada, [4], while examining renewable energy, argues for a conceptual reframing of the literature to consider ‘community of relevance’, [8] reviews public perceptions of energy technologies research, considering both large scale and customer-facing energy technologies, and [56] do a systematic review of the literature associated with the social acceptance of neighborhood scale distributed energy systems. These, and other, studies point to the importance of a multidimensional social acceptance research agenda to continue studying the deployment of advanced energy technologies and energy programs (in isolation and in systems) and to evaluate how the social acceptance of these technologies and programs evolve through interaction among multiple actors using multiple channels at multiple levels.

Indeed, coming out of this literature—and it is continuing to grow (and indeed accelerated by events of 2020, but more about that below)—are three key messages.

First, energy issues are multi-sector and multi-stakeholder, and different people will bring different understandings, different experiences, different priorities, and different lens to issues and projects. Thus recognize that people will see ‘the same things’ differently, and plan accordingly. Consider, for instance, a study by [22], who conducted a questionnaire study among 217 citizens living near the first publicly accessible hydrogen fuel station in the Netherlands. She found a range of emotions arising from the same project—varying levels of anger, fear, joy, and pride all arising from a hydrogen fuel station that was placed in the city of Arnhem in 2010. Of course, people are different, and their calculations will be informed by a variety of perceptions, understandings, and values (among other factors). It is nevertheless a useful reminder that multiple responses will almost certainly emerge within a population.

Second, effective engagement—between, for instance, proponents and residents for new energy projects—is critical. Engagement must be early, sustained, and meaningful. There must be multiple opportunities for information provision and two-way exchange, and commitments made must be fulfilled promptly and transparently. A number of those actively involved in siting transformative energy projects have published their own ‘how-to’ manuals regarding what they perceive to be effective community engagement. As but one example, consider the work of Australia’s Clean Energy Council. Being the industry association for that country’s renewable energy industry, the Council has collated resources that help project proponents build effective relationships with their host communities, arguing that trust and respect must be at the foundation [14].

And third, communication must be fulsome, truthful, and accessible. All involved must be committed to open dialogue and to working to agree on statements of fact and to clarify misunderstandings as quickly as possible. Indeed, such suggestions can be broadened to offer ‘best practices’ on communications more generally. [2], for instance, highlight the importance of what they call sociotechnical approaches to effective communications on a range of energy and environmental issues. A key message of theirs is that a broad understanding must be developed: breadth in the kinds of approaches that can be useful (technological, structural, and cognitive ‘fixes’), breadth in the kinds of actors sending and receiving communications (individuals, organizations, technologies), and breadth in the understanding of peoples’ engagement (motivations, attitudes, behaviors). This can be extremely useful to those taking forward particular transformative energy initiatives.

Research and analysis in this field have shown the importance of social acceptance to ensure that the right energy initiatives are adopted in timely, cost-effective, and sustainable ways. Recognizing differences among stakeholders and their perspectives, implementing effective engagement strategies, and communicating clearly will go a long way towards ensuring energy activity success.

As mentioned above, consideration of integrating social aspects of energy sustainability more fully—including those above—was accelerating in any case during the 2010s, but events during 2020 served to augment it even further. In the next section, I briefly review key events in 2020 and the broader societal changes they encouraged. Then, in the following section, I examine how those impacts—combined with all that has been presented in this chapter to this point—have effectively combined to construct an agenda for energy professionals going forward.

5 Events of 2020

The year 2020 was remarkable for a variety of reasons. The two reasons that I will focus upon here are the coronavirus crisis and the Black Lives Matter movement.

First, the World Health Organisation declared a global pandemic as a result of COVID-19 on 11 March 2020. As of November 2020 (the time of writing of this chapter), the global impact had been devastating. Most importantly, more than 1.3 million people had lost their lives, and 54.7 million people had been infected by the virus (figures from Johns Hopkins University, 16 November 2020). Economically, the world’s economy had contracted by 4.4% during 2020 (figure from the International Monetary Fund, 16 November 2020). Hundreds of millions of people had lost their livelihoods, and virtually no one had escaped impact: it was estimated that the physical and mental toll upon many would last for months, if not years, while the consequences for groups (be they communities, or countries, or regions) were both immediate and longer-term. Geopolitical reordering was looked to be another potential long-term consequence of the virus [63].

Second, on 25 May 2020, George Floyd—a black man—was killed in Minneapolis, United States by Derek Chauvin—a white police officer—while being arrested for allegedly using a counterfeit bill. Floyd’s death triggered worldwide protests against police brutality and systemic racism more generally. Collectively, the responses reignited the Black Lives Matter movement and directed greater attention to issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Indeed, the disproportionate impact of the global pandemic upon vulnerable communities was shocking to many; the fact that the United States was in the midst of a national election campaign provided additional platforms for discussions about equality and related issues [7].

Many had reflections upon how events like these in 2020 were changing global social and economic life in significant ways. Some investigations highlighted, for instance, the potential long-term impact upon the economy (e.g., [24]), upon the nature of work (e.g., [3]), and upon the role of technology (e.g., [30]). Building upon all of this reflection in wake of a remarkable 2020, I will highlight three areas that I believe are particularly important for those working to advance energy sustainability. They serve to help set the stage for the next section of this chapter, which advances a current set of priorities for energy professionals.

First, evidence-based decision-making is more important now than perhaps ever. Experience through the events of 2020 has demonstrated the value of rigorous and independent investigations that place a premium upon standards like validity and reliability. This sentiment was often voiced by different scientific and other associations during the year. For example, many US-based scientists wrote about the value of science, and the importance of an engaged and well-informed public [62].

Second, collaboration is vital. Again, experience during 2020 revealed that society often needs multiple perspectives—across disciplines, jurisdictions, ecosystems, and cultures—to solve problems and to embrace opportunities. It was shown that bright minds with different experiences, knowledge-bases, sets of resources, and ways of thinking coming together on challenges and opportunities are needed. Like many themes that climbed global agendas during 2020, this had previously been oft-noted—[37] had eloquently laid out the value of interdisciplinary approaches through diverse teams, and [18] was similarly impactful regarding the importance of international research.

And third, we must ensure that we leave no one behind. We need to ensure that those who are most vulnerable—individuals, households, communities, countries—are fully included as we move towards solutions and sustainable livelihoods; we must eliminate racism and discrimination of all kinds. Indeed, the concept of ‘co-creation’—of involving those impacted by issues, supported by evidence and expertise, in problem-solving—serves to integrate all three areas.

Much of the discussion around these, and associated, areas, came together in calls to ‘build back better’, ‘build forward better’, or undertake a ‘great reset’ (e.g., [36], [21], and [60]). Collectively, these were calls to acknowledge that, given the size of the impact upon economies and societies during 2020, communities around the world would—once they had the virus eradicated, or at least better controlled—have to ‘emerge’ and ‘rebuild’. Given this, there was also a widespread feeling that this crisis should be viewed as an opportunity: these same communities should not slavishly rebuild whatever it is that got torn down during 2020. Instead, they had the chance to determine what future was’best’—particularly in light of all that had been learned from the pandemic and Black Lives Matter experiences—and to move towards that new goal. Such recommendations should indeed be kept in mind as more specific work on energy innovations are carried out. It is in the next section where I make those connections.

6 Current Priorities for Energy Professionals

Given all of our learnings—learnings that were happening pre-2020 in any case, along with learnings that were catalyzed and/or revealed and/or effectively created by the 2020 pandemic—I offer, in this final substantive section, three interconnected priorities for researchers, analysts, managers, regulators, and others who have been attracted to the subject material in this book. In other words, because I envision readers of this book as being those who are at the forefront of knowledge with respect to innovation in advanced energy technologies—that is, technologies that power active networks, that catalyze greater use of renewable resources, and that improve energy efficiency—I offer three priorities for them to keep in mind. These are not priorities for the specifics of their work, but instead are priorities for how they place the work they are developing within its wider context—so that their contributions can be as impactful as possible. Accompanying each of the priorities, I point to some themes that appear to be set to be important as activity to advance energy sustainability continues. Let me also note that these priorities are also important for those who already work within this broader context to consider—the importance of context, and all of its constituents, should not be lost on anyone.

First, in the spirit of the aforementioned discussions to build forward better, a priority should be to ask, ‘what is the goal?’ As with much being discussed in this section, this issue was already moving toward the front of the proverbial energy consciousness—even before the events of 2020. Many were successfully challenging the traditional energy focus upon ‘supply’ by highlighting the importance of ‘demand’ as well. Indeed, a ‘whole system’ approach is now often—and rightly—taken in energy studies. This is to be encouraged further, and analysts would be wise to think about the ‘energy service’ that is ultimately desired; work can then proceed to determine what kind of system would best serve to meet this energy service requirement. (For elaboration and inspiration, see, for instance, the ‘system diagrams’ in [20].)

Moving forward, those working on energy projects will be increasingly asked, ‘Why is it being done this way?’ Assumptions, inertia, and comments like ‘That is how we’ve always done it’ will no longer pass muster (if they ever did). Demands for social and economic accountability will require respondents to speak to the energy services to which they are contributing, and the reasons why.

Second, in addition to recognizing how the issue upon which one is working sits within the broader energy system, recognize, as well, the importance of how the issue is connected to other issues—particularly (in this case), in terms of spatial connections and sectoral connections.

Regarding spatial connections, recognize that most energy issues have local, regional, national, international, and global dimensions involving a whole range of players. Put more academically, the term ‘multilevel governance’ is one with which those working on energy projects should be familiar. To clarify, it is usually the case that any particular energy system of interest will have linkages that reach across borders, so multiple jurisdictions (and their associated players—be they governments, businesses, civil society organizations, or others) have their particular stakes in the outcomes. Opportunities and challenges—catalysts and constraints—will be presented by these different governance players working at these different levels. As a case in point, energy politics in North America can often have local flashpoints (e.g., the siting of a power plant), intra-regional elements (e.g., plans to integrate electricity markets), trans-border dimensions (e.g., varying definitions of ‘renewables’ in different jurisdictions’ policies), and continent-wide elements (e.g., discussions about a large-scale power grid), each of which can be connected to the other [33].

Sectorally, let me reemphasize that while energy service provision is a goal in itself—indeed, a priority Sustainable Development Goal, as reviewed above—it is nevertheless also connected with multiple other goals that society is trying to advance. All would be wise to evaluate explicitly how energy ambitions impact these other priorities; the Sustainable Development Goals may well be a useful means to frame that investigation. While the discussion above already highlights works that show connections between SDG7 (energy) and other SDGs, Table 4 points to a few, in particular, that may be particularly relevant for readers of this book. Going forward, it will be critical to engage with others in an interdisciplinary manner to discover pathways to win-wins for sustainability.

And third, resilience is critical. Going forward in virtually every part of our lives—energy activities included—we will have to expect the unexpected. Consequently, we will have to build our energy research, our energy projects, our energy policies, and our energy institutions to be as nimble, flexible, and adaptable as possible. The year 2020 has shown us that low probability and high-risk events do indeed occur. And even before 2020, a number of observers had identified a range of such events that could happen—pandemics included. Indeed, in the World Economic Forum’s annual analysis of global risks, ‘infectious diseases’ was—at the beginning of 2020—in a quadrant characterized by ‘higher impact’/’lower likelihood’ risks; ‘weapons of mass destruction’, ‘information infrastructure breakdown’, and ‘food crises’ were the other global risks in that same quadrant [61]. Indeed, all 31 risks presented on the landscape warrant attention.

So, in summary, a message to energy professionals is to work with purpose, to identify and to respond to connections, and to embed resilience in their work going forward.

7 Summary and Conclusions

The purpose of this chapter has been to investigate sustainability within the context of transformative energy systems. To do this, the scene was set by investigating sustainability, generally, and energy sustainability specifically (with a further focus upon social acceptance issues). More recent events—namely, the remarkable developments during 2020—were briefly described, and some of their key impacts were identified. This—and, indeed, all the material in the chapter—then led into a discussion of the current sustainability agenda for those working directly in the energy sector. The motivation for the inclusion of this discussion was to ensure that energy professionals’ efforts—which often focused upon a relatively small part of the broader landscape—had a maximum impact going forward.

Energy is central to human existence and well-being. The sustainable provision of critical energy services will continue to be a key priority for communities in the future. Success in this regard will be important in helping to advance everyone’s well-being and communities’ collective livelihoods. Regardless of the extent to which one’s work involves energy issues, all need to understand, generally, the systems at work, and—at a minimum—connect with those who have more detailed knowledge. Collectively and collaboratively, we can, together, move towards a sustainable future.

References

Abbott KW, Bernstein S (2015) The high-level political forum on sustainable development: orchestration by default and design. Global Pol 6(3):222–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12199

Abrajamse W, DarbyS MKA (2018) Communication is key: how to discuss energy and environmental issues with consumers. IEEE Power Energ Mag 16(1):29–34. https://doi.org/10.1109/MPE.2017.2759882

Autor D, Reynolds E (2020) The nature of work after the COVID crisis: too few low-wage jobs. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

Batel S (2018) A critical discussion of research on the social acceptance of renewable energy generation and associated infrastructures and an agenda for the future. J Environ Planning Policy Manage 20(3):356–369

Bibri SE, Krogstie J (2017) Smart sustainable cities of the future: an extensive interdisciplinary literature review. Sustain Cities Soc 31:183–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2017.02.016

Biermann F, Kanie N, Kim RE (2017) Global governance by goal-setting: the novel approach of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Curr Opinion Environ Sustain 26–27:26–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.010

Blain KN (2020) Civil rights international: the fight against racism has always been global. Foreign Aff 99(5):176–181

Boudet HS (2019) Public perceptions of and responses to new energy technologies. Nat Energy 4:446–455. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-019-0399-x

Boyer RHW, Peterson ND, Arora P, Caldwell K (2016) Five approaches to social sustainability and an integrated way forward. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090878

C40 (2020) C40 cities, https://www.c40.org/. Accessed 14 Nov 2020

Campos-Guzmán V, García-Cáscales MS, Espinosa N, Urbina A (2019) Life cycle analysis with multi-criteria decision making: a review of approaches for the sustainability evaluation of renewable energy technologies. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 104:343–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.01.031

Castor J, Bacha K, Nerini FF (2020) SDGs in action: a novel framework for assessing energy projects against the sustainable development goals. Energy Res Soc Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101556

Chomsky N, Pollin R, Polychroniou CJ (2020) Climate crisis and the global green new deal. Verso Books, Brooklyn, NY

Clean Energy Council (2020) Community engagement. https://www.cleanenergycouncil.org.au/advocacy-initiatives/community-engagement. Accessed 15 Nov 2020

Devine-Wright P, Batel S, Aas O, Sovacool B, LaBelle MC, Ruud A (2017) A conceptual framework for understanding the social acceptance of energy infrastructure: insights from energy storage. Energy Policy 107:27–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.04.020

Florini A, Sovacool B (2009) Who governs energy? The challenges facing global energy governance. Energy Policy 37(12):5239–5248

Gaede J, Rowlands IH (2018) How ‘transformative’ is energy storage? Insights from stakeholder perspectives in Ontario. Energy Res Soc Sci 44:268–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.05.030

Gast AP (2012) Why science is better when it’s international. Sci Am 306(5):14–15

Gibson RB (2006) Beyond the pillars: sustainability assessment as a framework for effective integration of social, economic and ecological considerations in significant decision-making. JEAPM 8(3):259–280. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1464333206002517

Grubler A , Johansson TB, Muncada L, Nakicenovic N , Pachauri S , Riahi K , Rogner H-H, Strupeit L (2012) Chapter 1: Energy primer. In: Team, GEA Writing (eds) Global energy assessment: toward a sustainable future (October 2012). Cambridge University Press and IIASA, pp 99–150

Huang Z, Saxena SC (2020) Can this time be different? challenges and opportunities for Asia-Pacific economies in the aftermath of COVID-19. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok

Huijts NMA (2018) The emotional dimensions of energy projects: anger, fear, joy and pride about the first hydrogen fuel station in the Netherlands. Energy Res Soc Sci 44:138–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.04.042

IEA (2020) World energy outlook 2020. International Energy Agency, Paris

IMF (2020) World economic outlook: a long and difficult ascent. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

IRENA (2020) Long-term energy scenarios (LTES) network. https://www.irena.org/energytransition/Energy-Transition-Scenarios-Network. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Lafferty MW, Eckerberg K (2009) Introduction: the nature and purpose of ‘Local Agenda 21.’ In: Lafferty WM, Eckerberg K (eds) From earth summit to local agenda 21: working towards sustainable development. Earthscan, London, pp 1–14

Linnér B-O, Selin H (2013) The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development: forty years in the making. Environ Plann C Government Policy 31(6):971–987. https://doi.org/10.1068/c12287

Lovins AB (1976) Energy strategy: the road not taken. Foreign Aff 55:65–96

McCollum DL et al (2018) Connecting the sustainable development goals by their energy inter-linkages. Environ Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaafe3

McKinsey & Company (2020) The recovery will be digital: digitizing at speed and scale. McKinsey Global Publishing, New York City

Meadowcroft J (2007) National sustainable development strategies: features, challenges and reflexivity. Eur Env 17:152–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.450

Mensah J (2019) Sustainable development: meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: literature review. Cogent Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1653531

Mildenberger M, Stokes LC (2019) The energy politics of North America. In: Hancock KJ, Allison JE (eds) The Oxford handbook of energy politics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Mueller JT, Brooks MM (2020) Burdened by renewable energy? a multi-scalar analysis of distributional justice and wind energy in the United States. Energy Res Soc Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101406

Nerini FF et al (2018) Mapping synergies and trade-offs between energy and the sustainable development goals. Nat Energy 3:10–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-017-0036-5

OECD (2020) Building back better: a sustainable, resilient recovery after COVID-19. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

Phillips KW (2014) How diversity makes us smarter. Sci Am 311(4):43–47

Quitzow L et al (2016) The German Energiewende: what’s happening? introducing the special issue. Utilities Policy 41:163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2016.03.002

Rahman MM, Hettiwatte S, Shafiullah GM, Arefi A (2017) An analysis of the time of use electricity price in the residential sector of Bangladesh. Energ Strat Rev 18:183–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2017.09.017

Redclift M (2005) Sustainable development (1987–2005): an oxymoron comes of age. Sustain Dev 13:212–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.281

Sachs JD, McArthur JW (2005) The Millennium project: a plan for meeting the millennium development goals. The Lancet 365:347–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17791-5

SEI (2020) Planetary boundaries research. https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html. Accessed 10 Nov 2020

Seyfang G (2003) Environmental mega-conferences—from Stockholm to Johannesburg and beyond. Glob Environ Chang 13(3):223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(03)00006-2

Strengers Y (2014) Smart energy in everyday life: are you designing for resource man? Interactions 21(4):24–31. https://doi.org/10.1145/2621931

UNDP (2016) Delivering sustainable energy in a changing climate. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), New York

UNDP and ETH Zürich (2018) Derisking renewable energy investment: off-grid electrification. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), New York and ETH Zürich, Energy Politics Group, Zürich

UNEP (2015) The emissions gap report 2015. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Nairobi

United Nations (2020a) Millennium Development Goals and beyond 2015. https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/bkgd.shtml. Accessed 10 Nov 2020

United Nations (2020b) The Millennium Development Goals report 2015. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/mdg/the-millennium-development-goals-report-2015.html. Accessed 10 Nov 2020

United Nations (2020c) 17 goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/. Accessed 10 Nov 2020

United Nations (2020d) Goal 7. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal7. Accessed 10 Nov 2020

Upham P, Oltra C, Boso À (2015) Towards a cross-paradigmatic framework of the social acceptance of energy systems. Energy Res Soc Sci 8:100–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.05.003

Van de Graaf T (2013) The politics and institutions of global energy governance. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Van de Graaf T, Colgan J (2016) Global energy governance: a review and research agenda. Palgrave Communications. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2015.47

van Renssen S (2020) The hydrogen solution? Nat Clim Chang 10:799–801. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0891-0

von Wirth T, Gislason L, Seidl R (2018) Distributed energy systems on a neighborhood scale: reviewing drivers of and barriers to social acceptance. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 82:2618–2628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.09.086

Waage J et al (2010) The Millennium Development Goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015. The Lancet 376(9745):991–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61196-8

WEC (2020) World energy trilemma index. World Energy Council, London

WEF (2020a) Fostering effective energy transition. World Economic Forum, Geneva

WEF (2020b) The great reset. https://www.weforum.org/great-reset. World Economic Forum, Geneva. Accessed 22 Nov 2020

WEF (2020c) The global risks report 2020. World Economic Forum, Geneva

Weymann RJ, Santer B, Manski CF (2020) Science and scientific expertise are more important than ever. Scientific American, 5 August 2020, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/science-and-scientific-expertise-are-more-important-than-ever/, Accessed 16 Nov 2020

WHO (2020) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019, Accessed 16 Nov 2020

World Bank (2020) Tracking SDG7: the energy progress report. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Washington, DC

Wüstenhagen R, Wolsink M, Burer MJ (2007) Social acceptance of renewable energy innovation: an introduction to the concept. Energy Policy 35(5):2683–2691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2006.12.001

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rowlands, I.H. (2022). Sustainability and Transformative Energy Systems. In: Zambroni de Souza, A.C., Venkatesh, B. (eds) Planning and Operation of Active Distribution Networks. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, vol 826. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90812-6_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90812-6_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-90811-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-90812-6

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)