Abstract

Environmental teaching must deepen and widen students’ understandings on how the rest of Nature is affected by human actions and, consequently, upon each other as we are part of Nature. However, many environmental pedagogies do not critically teach to better understand the inseparable connections between environmental and social violence, and us dominating Nature. Critical, Freirean-based ecopedagogy is essential to read the complex, politically hidden dynamics of socio-environmental actions that lead to injustices and unsustainability (i.e., ecopedagogical literacy). Ecopedagogical reading includes decoding how racism, post-truthism, globalizations, neo(coloniality), patriarchy, heteronormativity, xenophobia, epistemicide, neoliberalism, and their intersectionalities falsely justify socio-environmental injustice and planetary unsustainably. I argue how critical theories are essential within environmental pedagogies, as well as research upon them, for students’ praxis to emerge for determining and doing actions needed to save Earth.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Ecopedagogy

- Environmental pedagogies

- Education for sustainable development (ESD)

- Critical literacy

- Paulo Freire

- Education for development

- Ecopedagogical literacy

Introduction

This chapter problematizes the need for critical-based environmental pedagogies to deepen and widen students’ understandings of the politics of environmentalism and development grounded in sustainability within the world (i.e., all humans, human population) as part of Earth (i.e., all of Nature).1,2 Sustainability emphasized here is globally holistic and planetarily balanced with the rest of Nature. Pedagogical deconstruction of the politics of environmental violence, especially systematically hidden politics, is essential to understand the deeper reasons why environmental violence occurs. Human acts of environmental violence would not occur without benefiting some person(s)/population(s). For example, deep-ocean oil drilling would be senseless unless there were benefits because it leads to numerous socio-environmental injustice and planetary unsustainability issues. In this chapter, I argue the need for, and discuss the grounding tenets of, ecopedagogy for teaching critical literacy to read who benefits from environmentally violent acts, who suffers from them, and how does the acts affect Nature both anthropocentrically and planetarily (i.e., human-centric and beyond humans)—ecopedagogical literacy.

Ecopedagogical reading problematizes how coinciding and contrasting framings of ‘development’ result in differing populations benefiting or suffering, and (un)sustainability globally and planetarily (Misiaszek, 2015, 2020d). Reading ‘sustainability’ critically questions at what level do we sustain and is the level determined by justice, laws of Nature, and/or oppressive ‘development’ framings? Such questioning leads to asking what would be the socio-environmental outcome if the lower socio-economic 90%+ of the population had the lifestyles of the top 10%? Without question, it would lead to total environmental devastation. The top 10% can only accomplish such unsustainable ‘lifestyles’ on the backs of the masses. Ecopedagogy is an essential element of social justice pedagogies because environmentally violent actions are inherently political and most often benefit the few powerful while negatively affecting the vast powerless masses, aligning with unjust hierarchical power structures stemming from hegemony.

This chapter does not give enough space to delve into all aspects of ecopedagogies, as well as its practices, theories, and methodologies to (un)teach ‘development’ and ‘sustainable development.’ What will be focused upon key critical-based needs for environmental pedagogies with primary focus on Freirean-based ecopedagogy. I will first briefly give a brief overview of ecopedagogy and then discuss some of the key aspects.

Ecopedagogy

Ecopedagogies are critical, transformative environmental pedagogies that center praxis to end unsustainable environmental violence,3 guided by deepened and widened understandings of our world within Earth. Although plural in framing, ecopedagogies emerged from Paulo Freire’s popular education models of Latin America and his direct work on ecopedagogy in his later work (Gadotti, 2008b; Gutiérrez & Prado, 2008; Misiaszek, 2012; Misiaszek & Torres, 2019). Due to this chapter’s rather short word-length constraints, I will not delve deeply into defining Freirean groundings within ecopedagogy, but rather I will discuss how and why his work and reinventions of his work are essential for teaching environmentalism and sustainable development.

Below is my definition of ecopedagogy.

Ecopedagogy is essentially literacy education for reading and rereading human acts of environmental violence with its roots in popular education, as they are reinventions of the pedagogies of the Brazilian pedagogue and philosopher Paulo Freire. Ecopedagogies are grounded in critical thinking and transformability, with the ultimate goal being to construct learning with increased social and environmental justice. Rooted in critical theories and originating from popular education models of Latin America, ecopedagogy is centered on better understanding the connections between human acts of environmental violence and social violence that cause injustices/oppressions, domination over the rest of Nature, and planetary unsustainability. [Better understanding is] through the aspect of deepening and widening understandings from different perspectives, ranging from the Self to local, to national, to global, to the planetary (Misiaszek, 2018). With this widening there is the aspect of environmental well-being—of not just ourselves and our communities, but of all of human populations together and Earth overall —which, as explained by Neera M. Singh (2019), calls for an extension of NIMBY to NIABY worldwide and NOPE that has a planetary scope. (Misiaszek, 2020c, pp. 16–17)4

Ecopedagogical literacy is for deepening and widening understandings of environmental violence to determine necessary transformative action emergent from critical theorizing (i.e., praxis), rather than environmental pedagogies that focus on students gaining environmental knowledges quantitatively (Misiaszek, 2012, 2015).

Ecopedagogical work is both deepening and widening understandings for praxis toward balance with the rest of Earth and socio-environmental peace for the world. Reading the world locally to globally, as part of Earth-as part of the planetary sphere-is the essence of ecopedagogical work. Ecopedagogical work should widen our world as part of Earth, with our actions in the name of ‘development’ problematized within the planetary sphere. Such planetary perspectives are widened from critical global perspectives in which we act for socio-environmental justice for all the world-inclusive of all human beings. But it also includes the need for deepened understandings of locally contextualized perspectives. (Misiaszek, 2020c)

How (in)(non)formal education sustains, intensifies, or counters world-Earth unsustainability is essential to continuously (re-)read. Ecopedagogical reading must happen through socio-historical and local-to-global-to-planetary lenses, as well as knowledges we have of Earth beyond our world (i.e., facts and ‘laws’ of Nature that are not subjectively mendable by humans). Local-to-global ecopedagogical reading problematizes how socio-historical oppressions (e.g., coloniality, racism, patriarchy, neoliberalism, globalization from above, non-/citizenship othering, heteronormativity) have created, sustained, and intensified socio-environmental ills and planetary unsustainability. Critical pedagogies, such as ecopedagogues, have the goal of ending oppressions by centering the understanding unjust struggles from those who suffer from them (Gadotti, 1996).

As emphasized here, ecopedagogical literacy is not only for reading to better understand socio-environmental ills but for transformative praxis to end them. Ecopedagogues teach through problem-posing societies’ structures for praxis with deepened and widened reflectivity on possibly actions for socio-environmental transformation within the anthroposphere. Social and environmental violence’s inherently inseparability highlights the need for teaching to disrupt distancing that justifies environmental violence and planetary unsustainability. Distancing (e.g., geographically, time-wise, othering) of environmental violence’s causes and effects from one’s self and community is too-often ideologically taught to falsely justify injustices and unsustainable development. Teaching for de-distancing innately grounds ecopedagogical work for unlearning ideological “reasoning” for unsustainable environmental violence (Misiaszek, 2012, 2020c).

Differing from Other Environmental Pedagogies

Environmental pedagogies (e.g., environmental education [EE], education for sustainable development [ESD], ecopedagogy) are often publicly viewed as interchangeable; however, the essence of each and the politics of specific approaches to them are essential. Environmental teaching is inherently political with differing processes, goals, and practices, which form contested terrains of teaching socio-environmental justice, sustainable development, and/or planetary sustainability. EE models have historically been critiqued for overlooking oppressive social issues caused by environmentally harmful acts (McKeown & Hopkins, 2003). ESD models emerged largely to focus teaching on how environmental issues affect societies to better understand how actions for development can minimize the negative environmental outcomes—“‘sustainable’ ‘development.’”

The critical deconstruction of politics grounding ecopedagogies does not only define ecopedagogical research but also is part of ecopedagogical spaces. In other words, problematizing what is learned from environmental pedagogies and pedagogies on the environment5 must be critically deconstructed to truly understand their ideological foundations. This includes problematizing how do the politics of both pedagogies positively and/or negatively affect subjectivity within our world with the rest of Nature’s non-subjectivity (i.e., non-reflectivity due to the lack cognitive abilities of everything outside of human beings). Environmental pedagogues that teach for environmental violence apolitically fail to teach why they happen in order to benefit, frequently, only a few while many other suffer and Nature is destroyed.

The simplification of answering this question and the separating social and environmental oppressions in learning space are political pedagogical tools to rationalize injustices and unsustainability. As discussed previously, environmental justice is inseparable from social justice, environmental violence inseparable from social violence, and planetary sustainability is inseparable from peace; however, many pedagogies often distance these inherent connections. Shallow teaching through apoliticization and distancing happens in various ways, including placing environmental devastation into a single disciplinary and a single, often dominant, epistemological framing (Misiaszek, 2012). By disrupting environmental pedagogies that impede deconstructing the politics of unsustainable environmental violence, ecopedagogical reinventions allow for students to determine what is needed to be done to disrupt the violence itself.

Planetary Widening

Ecopedagogy might be initially viewed as being anthropocentric by focusing on politics within our world; however, it is planetary because its widened perspectives of how our politic affects the rest of Nature affecting ‘us’ (anthropocentrically) and beyond humans’ interests (non-anthropocentrically). It is humans’ actions for socio-environmental (in)justice that determine (un)sustainability within the planetary sphere, including the world. Nature has the essence of being balanced with only humans as reflective entities that challenge this equilibrium. In short, human actions disrupt and challenge such balance (i.e., sustainability). Humans are also the source of justice and injustice for the world-Earth, as the rest of Nature cannot offer (in)justice without being able to be reflective (Warren, 2000)—or as Freire (2000) argued, absent of histories and cognition to act upon one’s own dream (i.e., utopia and education arguments). For example, a wolf attacking a child due to hunger, or a typhoon destroying a town. Although both are tragic, the wolf and typhoon do not happen through reflectivity but due to survival and atmospheric air pressure systems returning to equilibrium.

Ecopedagogical planetarization of teaching problematizes knowledges and epistemologies that have our world within or outside of Earth as factors in determining actions for development. This includes too-often conceptualized goals of modernity the reside outside the concerns for the rest of Nature that, in turn, leads to ‘development’ framings without possibilities of planetary sustainability (Misiaszek, 2020e). Many critical scholars have argued this including Ivan Illich (1983) who, in his book Deschooling Society, argued that contemporary man has increasingly viewed himself outside Nature’s control as opposed to classical man who sometimes acted against Nature but recognized there would be consequences. A key question is how can environmental pedagogies counter entrenching ideologies of Illich’s contemporary (wo)man?

Outside the anthropocentric sphere, laws of Nature’s truths are static with our (i.e., humans’) perspectives as incomplete and politically subjective. Incompleteness stems from us not knowing all the complexities of Nature holistically, although we are, or should be, continuously trying to better understand all of Nature. Ecopedagogical work problematizes the politics of socio-environmental oppressions from the subjective historically constructed world upon Earth’s objective laws of Nature. This includes problematizing how is learning the static laws of Nature disrupted by falsely taught ideologies that the laws are fluid and mendable within humans’ subjectivity. In addition, self-reflectivity of the limitations of knowing the rest of Nature is also essential, with contemporary (wo)man too-often lacking such cognitive processing, especially with current intensification of post-truthism (a topic discussed more later).

d/Development

‘Development’ is too infrequently debated critically within and between contexts but is touted without critical reflection as rationalizing the need for socio-environmental actions. Ecopedagogical literacy centers the mapping of what defines ‘development’ as inherently political, socio-historical, and socio-environmentally dependent. ‘Sustainability’ is often brought into the argument to limit such actions; however, it is often overshadowed by economic development, especially within neoliberal globalization that normalizes world-Earth distancing. Examples of neoliberal world-Earth distancing occur whenever economic profit is overly valued above considering, if at all, the environmental devastation caused by the profiteering that only benefits specific population(s). A more specific example would be Northern mining operations within the Global South which do not care about the environmental effects upon the local populations but profit for the (trans-international) corporation with only a fraction of economic benefits received by the local mining population(s). In this example, Development distances environmental effects in all decision-making and thus ‘world-Earth distancing is occurring.’ Together, understanding ‘sustainable development’ is crucial to guiding action but only when it is taught and read critically, within a biocentric framing which is locally-to-globally-to-planetarily contextualized.

As ecopedagogical learning spaces are Freirean, teacher(s) and students democratically learn and teach together to understand ESD’s contested terrain of empowering and oppressive outcomes. There are various tenets of Freirean-based dialogue within these spaces. Ecopedagogical spaces are also inevitably full of conflict, with coinciding and contrasting thoughts of ‘good’ or ‘bad’ development, must be safe so students can have Freirean, authentic dialogue without feeling threatened. Coinciding with Freirean pedagogy, dialogue within ecopedagogical spaces counter ideologies that are viewed as ahistorical, apolitical, and epistemologically singular. It is essential to note that Freirean dialogue in learning spaces called for the end of teachers’ authoritarianism but not their authority, an important distinction, in which the former grounds banking education but not the latter (Freire, 1997, 2000).

Ecopedagogical tools problematize the politics of environmental violence that causes social oppressions within the world and Earth’s unsustainability. This includes ecopedagogical reading of the politics of ‘development’ and ‘sustainable development’, as well as actions emergent from them. The crucial question of teaching for “progress” is how the goal(s) are defined that are inherently better than the current situation(s) to teach toward. Ecopedagogical reading of the connections between human populations and the rest of the planet, to determine the connections between ‘development,’ ‘livelihood,’, and overall well-being to counter environmental violence that is inseparable to social violence/injustice (and vice versa) (Gadotti, 2008a, 2008b; Gadotti & Torres, 2009; Kahn, 2010; Misiaszek, 2011, 2018, 2020c, 2020d). In how we teach the concepts and possible actions toward “development” (or progress), teachers must problematize what (un)sustainable, (anti-environmental), and socio-environmental (un)just action are we ideologically promoting.

Disrupting development singularly framed and measured by hierarchical upward positioning compared to others and increased accumulation is a key goal ecopedagogy (Misiaszek, 2018, 2020d). Although such logic can be very much problematized, it is problematizing the defining masters by their slaves (a la Hegel), or by the numbers of people “beneath” them (false ‘success,’ a la Freire [2000]), in which liberation emerges from the “slaves” recognizing their own bottom-up power. Banking education, including shallow environmental pedagogies, systematically suppresses such power. This includes teaching toward oppression by ideologically framing labor and natural resource usage for Development to benefit the “masters” rather than development for themselves, humans overall, and planetary sustainability. The passage below briefly define d/Development differences:

…lowercased development and uppercased Development indicate, respectively, empowering versus oppressive, holistic versus hegemonic, just versus unjust, sustainable versus unsustainable, and many other opposing framings of who is included within “development” and framings of d/Development goals. There are no absolute origins or framings differentiating d/Development, but rather the essence and outcomes of their framings. (Misiaszek, 2020c)

Pinpointing, understanding, and then countering environmental violence for Development masked as development perverting education as the masking tool is a goal of ecopedagogical literacy (Misiaszek, 2018, 2020c, 2020d). Teaching to disrupt Development as development is an ecopedagogical foundation, as well as disrupting sustainability ideologies, models, and baselines that lead to Development rather than development.

Globalizations: Decoloniality or Neocoloniality

To teach deepened understandings of sustainable development and globalization, ecopedagogues must problem-pose how, as a global society, do we determine what to sustain and at what level of sustainability? In short, what are the baselines of ‘sustainability’ that is locally-to-globally-to-planetarily development and sustainable—a balance of being locally contextual, globally holistic, and planetarily aligned with the laws of Nature? Currently, are baselines determined through local and/or global lenses, as well as are they determined anthropocentrically or planetarity? I argue that making this determination through global lenses creates a deficit-framed determination of sustainability because global demands on local societies are almost always impossible and they structurally “export” socio-environmental ills (from the ‘globalizers’ to the ‘globalized’), thus creating distanced local societies unsustainable (Misiaszek, 2020d). Reproductive environmental pedagogies instilled upon the globalized are essential for sustaining/intensifying globalizers’ hegemony because such teaching avoids problematizing socio-environmental harmful effects from Development. These are effects from globalization from above; however, ‘globalization’ is best conceptualized as plural.

I utilize the plural term of globalizations, as Carlos Alberto Torres (2009) has framed, to indicate that processes of globalizations can be either empowering or disempowering (e.g., globalizer/globalized, from below/from above) and thus demand rigorous, contextual analysis to better understand who/what6 are negatively or positively affected. Reading how the contested terrain of globalizations affects local societies both currently and historically is essential to better understand the multilayered dynamics of unsustainable environmental violence.

There are various reasons for needing the analysis of processes of globalization (mis)guiding sustainable d/Development and (anti-)environmentalism. One of the most obvious reasons is that environmental ills do not respect geo-political borders, especially the term’s “-political” part. Countering the myth that globalization and education research is through only macro-lenses, micro analysis through local lenses on how globalizations’ affects local communities is central. Distancing socio-environmental effects upon far away local populations is aligned with Giddens (1990) famous defining of globalization in which he centers global “link[ing]” effects upon “distant localities… many miles away and vice versa.”7 The need to understand the commonalities and differences between what diverse populations view as socio-environmental development is essential with the recognition that environmental issues are almost always never contained locally and are often globally far-reaching in their effect.

As discussed previously, histography is an essential part of ecopedagogical work and disrupting coloniality for decolonial praxis cannot be absent from this work. What is necessary in analyzing globalization within a “postcolonial” world is how its processes can counter colonial-structured education oppressions rather than often sustaining such oppressions arising from neocoloniality (Abdi, 2008). Ecopedagogy inherently counters globalizations from above, which can be fittingly termed as neocoloniality, through acts of unsustainable environmental violence.

There are innumerable socio-historical aspects of oppressions from colonializations and globalizations that can be characterized as neocolonial with Development ideologies purposely taught as development. Teaching to better determine the oppressive and empowering framings of development is largely through analyzing histories of defining d/Development, as well as false ideological teaching to veil development for oppressive Development to continue without protest. In short ([EPAT 2020—PT], neocolonial global governance purposely discourages possibilities of localized democratic participation [Dale, 2005]).

Although impossible to fully know, understanding histories of colonialism that had led to socio-environmental injustices for the (neo)colonialized and planetary unsustainability are unceasing ecopedagogical goals. Key to this goal is dismissing the myth that the world has been wiped clean from coloniality’s thick residue (Grosfoguel, 2008). Without decoloniality, environmental pedagogies become/remain tools to sustain (neo)coloniality and coinciding Development (Misiaszek, 2020c, 2020d).

Epistemological (Re)reading and (Un)learning

Ecopedagogues utilize the work of post-/de-colonial scholars such as de Sousa Santos (2007, 2016, 2018) and Raewyn Connell (2007, 2013) on epistemologies of the South that inherently counter pedagogies and associated research based on epistemologies of the North. Ecopedagogical literacy includes reading what epistemologies are socio-environmental “knowledges” being taught through, including the socio-historical grounding of the ways of knowing as Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2018) differentiates between those of the South and North (Misiaszek, 2019). Processes of legitimizing knowledges and ways of knowing Earth, paralleling globalizations’ contested terrain, can be inside, outside and/or between epistemologies of the South and those of the North. The innate hegemonic dominance of epistemologies of the North negates epistemological diversity, which de Sousa Santos (2018) termed epistemicide, thus countering diverse epistemological teaching, reading, and praxis (a.k.a., ecologies of knowledges). Reworded in my own terminology in this chapter, ecopedagogical work needs to de-distance (or legitimize) epistemologies of the South to counter epistemologies of the North.

Ecopedagogical deconstruction of the politics of epistemological (de)legitimization is essential to understand how specific knowing leads toward socio-environmental injustices and unsustainability due, in part, to how anthropocentricism, world-Earth distancing, and Development are shaped and reinforced. These influences are not absent in academic scholarship as disciplinary foundations must be epistemologically problematized for what de Sousa Santos (2018) argued as disciplinary absences for needed disciplinary emergences to materialize in transformational and often radical ways. This chapter does not provide the space to elaborate upon the complexities between epistemologies of the South/North; but below de Sousa Santos (2018) described epistemologies of the North—grounded in coloniality, patriarchy, and capitalism—from epistemological perspectives of the South:

From the standpoint of the epistemologies of the South, the epistemologies of the North have contributed crucially to converting the scientific knowledge developed in the global North into the hegemonic way of representing the world as one’s own and of transforming it according to one’s own needs and aspirations. In this way, scientific knowledge, combined with superior economic and military power, granted the global North the imperial domination of the world in the modern era up to our very days. (2018, p. 6)

De Sousa Santos (2018) argues that epistemologies of the South exist to counter epistemologies of the North to sustain/intensify coloniality, patriarchy, and capitalism. Such epistemological analysis coincides with Edward Said’s (1979) Orientalism, and arguments from decoloniality scholars such as Albert Memmi and Franz Fanon.

De Sousa Santos directly argued that epistemological hegemony, leading to epistemicide, cannot lead to environmentalism or sustainability in the following quote:

Nature, turned by the epistemologies of the North into an infinitely available resource, has no inner logic but that of being exploited to its exhaustion. For the first time in human history, capitalism is on the verge of touching the limits of nature. (Santos, 2016, p. 19)

Traditional sociological goals are to deepen and widen our understandings of the anthroposphere. However, ecopedagogical work bends and stretches the sociology beyond anthropocentricism that, in turn, challenges its foundation(s) (such as capitalism above) which cannot be done within the absences from epistemologies of the North. Because humans are part of Earth, true sustainability cannot singularly lie within our own understandings from interactions both with one another as social beings and us with the rest of Nature, but also outside of our world and cognitive reflectivity. It is important to note ecopedagogical literacy must be through ecologies of knowledges for deepened and widened self-reflectivity, because reading must not only strengthen previously held epistemological foundations but also challenge them. And, sometimes needing to unlearn them. With global dominance, this means that reflectivity is most frequently bounded by epistemologies of the North that, as argued previously, cannot lead to environmental justice or sustainable development due to the entrenchment of coloniality, patriarchy, and capitalism.

Economics: Justice and Sustainability, Versus Neoliberalism

Ecopedagogical work must deconstruct local-to-global economics to determine praxis for economics saturated with goals for socio-environmental justice, development, and Earth’s well-being beyond anthropocentricism. Economics also form a contested terrain of models; however, ecopedagogues are inherently the nemeses to neoliberal economics—capitalism on steroids. Roger Dale (2018) argued that “[a]t base, the ‘global’ does not represent the universal human interest, but the interests of capitalism; it represents particular local and parochial interests which have been globalized through the scope of its reach” (p. 68). Streeck et al. (2016) exemplify this by arguing that the West has:

de-coupl[ed] the fate of the rich from that of the poor; the plunder[ed] of the public economy, which had once been both an indispensable counterweight and a supportive infrastructure to capitalism, through fiscal consolidation and the privatization of public services (Bowman, 2014); systemic de-moralization; and international anarchy. (p. 167)

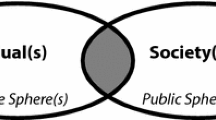

Neoliberalism only centers the Self’s private sphere to, in turn, devalue all of the public spheres, including the vastest sphere of Earth holistically (Postma, 2006).

For example, neoliberal-grounded environmental pedagogies (an oxymoron) solely problematize socio-environmental ills upon economics to sustain and intensify hegemony without concerns that ground ecopedagogies. It is important to note that teachers are often uncritically unaware of neoliberal ideologies being instilled by them, coinciding with arguments of deeply engrained epistemologies of the North to be taken as apolitical and without alternatives. Neoliberalism continues to exist by having environmental teaching that blocks critical questioning its ideology, hiding who really benefits, suppresses knowledge on the vastness of suffering, and instilling that there are no alternatives to neoliberalism or neoliberal-framed Development. Neoliberalism innately distances ‘us’ from one another and from the rest of Nature (i.e., world-Earth distancing). Ecopedagogues teach to problematize and critically reading what is “development” and “livelihood” including and beyond the realm of economics, to better understand the environmental burden that those who “have” place upon the “have-nots.” and upon the rest of Nature. Teaching through rigorous theorizing of otherness and oppressions emergent from ‘development’ ideologies is essential to disrupt normalized neoliberal-grounded livelihood and Development.

Ecopedagogical lessons for development must include the discussions within and between private and public spheres, as well as a continuum of citizenship spheres from local to planetary. This includes juxtaposition problem-posing of livelihood as dis/commented with framings of d/Development. Neoliberalism’s infatuation of the private sphere, the public sphere, traditionally defined as the relationship between citizens and the State, negatively, as a non-private sphere, devalues both in priority and in action (Capella, 2000; Postma, 2006). Livelihood framings construct our developments’ goals, with specific focus on neoliberalism, through our roles and responsibilities as citizens (from local-to-planetary spheres) within private and public spheres. Citizenships is the topic of the next section.

Citizenships: Local-to-Planetary

Histories of citizenship have created solidarity with populations, but too commonly it’s through othering of “non-citizens” initializing and continuing public education ideological training aligning non-/citizens with socio-historical oppressions. Ecopedagogical work problematizes how can constructs of citizenship both deepen our understandings and solidarity for one another beyond the traditional framings of citizenship and for the rest of Nature.

I (2012, 2015, 2018) have argued that citizenships’ plurality is essential, indicating local-to-global-and-planetary citizenship spheres.

The inclusion of citizenship is not singular; it could be framed as inclusive of different degrees of civil connectedness between planetary, global, and nation-state citizenships. Such incorporations are necessary for social-environmental well-being to exist. (Gutiérrez & Prado, 1989; Misiaszek, 2015, p. 281)

Solidarity is a core aspect of citizenship, and looking at the concept of livelihood through various spheres leads to an expanded view of progress and what should be sustained through multiple levels, from local to planetary. Moacir Gadotti defined planetary citizenship as “an expression that was adopted to express a group of principles, values, attitudes and habits that reveal a new perception of Earth as a single community” (2008a, p. 8). Planetary citizenship highlights the need for ecologies of knowledges, as epistemologies of the North objectify and commodify Nature for profit within systems of capitalism. Education for Development is development for only, at the very most, those considered as ‘fellow citizens’ without concern of deemed non-citizens’ de-development or, even less, the devastation of nature (purposely lower-cased).

Planetary citizenship helps us to acknowledge that focusing on justice and peace only within the anthroposphere is problematic, thus objectifying the rest of Nature and separating ‘us’ as the sole determining factor. This previous sentence is actually impossible due to social-environmental inseparably as argues throughout this chapter, as peace within the anthroposphere is impossible without planetary peace/sustainability. For such planetary solidarity, we must teach through epistemologies, disciplines, perspectives, and fields that are often ignored, as well as ecopedagogically reading why such ignorance is systematically constructed. Examples of largely dismissed ‘items’ within many environmental pedagogies include the following important aspects within ecopedagogies: the ‘residue’ of the philosophies, ecolinguistical analysis on how we utter all that is non-human (e.g., ‘who’/‘what’, ‘Earth’/‘the earth’), epistemologies of the South that counter the objectification of Nature, and an overly humanizing characterization of Nature (e.g., conserving only esthetically pleasing animals and environments rather than see the values of diverse ecosystems).

Post-Truthism

The increased rise of post-truthism within environmental public pedagogy is one of ecopedagogues’ greatest threats needing to be countered. Post-truthism centers false ‘truths’ solely emergent from specific ideologies not grounded in truth-seeking, without listening to authentic others’ truths, perspectives, and realities, or within the known laws of Nature. Critically reading how post-truthism constructs socio-environmental knowledges and associated framings of development that deceptively touts opinioned-falsities as truths, is increasingly essential as post-truthism seems to be spreading at expediential rates. This leads to the following key concern: how can critical, authentic dialogue occur in the post-truth era? Post-truthism obliterates any baseline of agreed upon facts for dialogue to exist, critical or otherwise. Ecopedagogical spaces that center critical, authentic dialogue is the enemy of post-truthism.

Post-truth falsifies Development as benefiting the masses and planetary sustainability as unimportant at best and absolute denial at worse, too-often saturated with conspiracy theories. From epistemological hubris of the North, post-truthism has intensified with false lessons that opinions from our subjective world will alter the laws of Nature which have outcomes absent of any subjectivity (Misiaszek, 2020a). Ideological opinions replace facts in post-truthism to reject ‘truths’ that counters self-determined benefits within a specific ideology(ies) that oppose plural, multicultural understandings, and ignore or manipulate all other epistemologies that are self-contradictive. Within the realm of environmentalism, post-truthism often goes a step(s) further by blaming diversity and environmentally sound actions as causes of ‘our’ oppressions, rather than the actual culprit—unsustainable environmental violence.

Post-truth epistemologies strengthen ideological opinions rather than authentic pursuits for truths. Thus, epistemological framings emergent from post-truthism pervert world-Earth (mis)understandings confined to closed, ideologically singular ones. Post-truthism increasingly twists our understandings of nature to one’s ideological opinions to, quite literally, breaking them (i.e., outside of Apple’s [2004] defined basic rules as opposed to selectable preference rules). In addition, persons (un)consciously utilizing post-truthism either ignore incompleteness of knowledges as they discuss their opinions as truths or call upon incompleteness to ignore scientific truths that oppose their opinions.

Ecopedagogical work is essential to countering post-truth populism that falsely reconstructs truths and truth-seeking to coincide with Development. Such reconstructions are systematic, most frequently unknown by the those believing but systematically constructed for ideological coherence through instilling ignorance. Teaching to read the politics of such systematic ideological perversion that manipulates socio-environmental truths is an ecopedagogical goal; post-truthism is a sounding alarm of needing ecopedagogy with truths being entirely disregarded for ignorant, blinded devotion that will only lead to total environmental devastation.

Conclusion

Several scholars have argued that the Second World War marked two defining moments that emphasized the need of critical pedagogy to counter the blind following of authoritarianism that led to Nazism and the horrific Holocaust, and the first time the human race could blow the world entirely up with the invention of the atomic bomb (Pongratz, 2005). Scholars have also discussed this time in history as screaming the need for a Kuhnian paradigm shift toward peace education (Harris & Morrison, 2003). Although differing in contexts, untethered environmental violence is unquestionably leading us toward a bleak, fatalistic future in which the recognition of needing radical change and critical education for it may take place beyond the tipping point. Hopefully not. I (Misiaszek, 2020b, 2020f) have written that COVID-19 has provided us lessons on the devastative results when the rest of Nature is ignored due to politics of being ‘inconvenient’ to current social systems, especially guided by neoliberalism (e.g., shutdowns disrupt capitalism, health systems guided by humanistic concerns and medical knowledges rather than the market, solidarity of wearing masks to protect the most vulnerable prioritized rather than mask-wearing as an individualistic choice linked to ‘freedom’); however, if these lessons are widely learned remains largely to be seen. My arguments of needing Freirean-based ecopedagogy here in this chapter can be critiqued but needing environmental pedagogies for transformative action is an indisputable certainty.

Notes

-

1.

“Education” and “pedagogy(ies)” include schooling (i.e., formal education), but also non-formal and informal (i.e., public pedagogies) education.

-

2.

The article “the” will not be used with “Earth” to not linguistically objectify Earth and will be upper-case. Coinciding with “Earth,” Nature will be upper-cased.

-

3.

“Sustainable” here is important because there are continuums of environmental violence (e.g., from turning on a computer to mountain top removal [MTR] for mining).

-

4.

NIMBY: Not In My Backyard; NIABY: Not In Anybody’s Backyard.

-

5.

My own work on environmental pedagogies separates them that have goals of “being environmental” and pedagogies on the environment that teaches on the environment, but the goals can be either environmental or not (education, in both models, must include and be well beyond schooling, with in/non/formal pedagogies).

-

6.

The terms “who/what” is given to signify a biocentric framing of contextualizing globalization which does not only include human but also all other life beings and the non-organic natural world (e.g., landscapes, seascapes).

-

7.

Globalization as “the intensification of worldwide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa” (Giddens, 1990, p. 64).

References

Abdi, A. A. (2008). De-subjecting subject populations: Historico-actual problems and educational possibilities. In A. A. Abdi & L. Shultz (Eds.), Educating for human rights and global citizenship (pp. 65–80). State University of New York Press.

Apple, M. W. (2004). Ideology and curriculum (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Bowman, A. (2014). The end of the experiment? From competition to the foundational economy. Manchester University Press.

Capella, J.-R. (2000). Globalization, a fading citizenship. In N. C. Burbules & C. A. Torres (Eds.), Globalization and education: Critical perspectives (pp. 227–252). Routledge.

Connell, R. (2007). Southern theory: The global dynamics of knowledge in social science. Polity.

Connell, R. (2013). Using southern theory: Decolonizing social thought in theory, research and application. Planning Theory, 13(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095213499216

Dale, R. (2005). Globalisation, knowledge economy and comparative education. Comparative Education, 41(2), 117–149. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a772749155

Dale, R. (2018, September). Framing post-SDG prospects for ‘education for development’. Global Comparative Education: Journal of the World Council of Comparative Education Societies (WCCES), 2(2), 62–75.

Freire, P. (1997). Pedagogy of the heart. Continuum.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Gadotti, M. (1996). Pedagogy of praxis: A dialectical philosophy of education. SUNY Press.

Gadotti, M. (2008a). Education for sustainability: A critical contribution to the decade of education for sustainable development. University of São Paulo, Paulo Freire Institute.

Gadotti, M. (2008b). Education for sustainable development: What we need to learn to save the planet. Instituto Paulo Freire.

Gadotti, M., & Torres, C. A. (2009). Paulo Freire: Education for development. Development and Change, 40(6), 1255–1267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01606.x

Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford University Press.

Grosfoguel, R. (2008). Decolonizing political-economy and postcolonial studies: Transmodernity, border thinking, and global coloniality. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, 2008(80), 115–147.

Gutiérrez, F., & Prado, C. (1989). Ecopedagogia e cidadania planetária [Ecopedagogy and planetarian citizenship]. Cortez.

Gutiérrez, F., & Prado, C. (2008). Ecopedagogia e cidadania planetária. Instituto Paulo Freire.

Harris, I. M., & Morrison, M. L. (2003). Peace education (2nd ed.). McFarland.

Illich, I. (1983). Deschooling society (1st Harper Colophon ed.). Harper Colophon.

Kahn, R. (2010). Critical pedagogy, ecoliteracy, and planetary crisis: The ecopedagogy movement (Vol. 359). Peter Lang.

McKeown, R., & Hopkins, C. (2003). EE ESD: Defusing the worry. Environmental Education Research, 9(1), 117–128. http://www.informaworld.com/10.1080/13504620303469

Misiaszek, G. W. (2011). Ecopedagogy in the age of globalization: Educators’ perspectives of environmental education programs in the Americas which incorporate social justice models. Ph.D., University of California, Los Angeles, Dissertations & Theses: Full Text. https://search.proquest.com/openview/d2d5c04ffc0e8d63441b3a9797643b07/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (Publication No. AAT 3483199).

Misiaszek, G. W. (2012). Transformative environmental education within social justice models: Lessons from comparing adult ecopedagogy within North and South America. In D. N. Aspin, J. Chapman, K. Evans, & R. Bagnall (Eds.), Second international handbook of lifelong learning (Vol. 26, pp. 423–440). Springer.

Misiaszek, G. W. (2015). Ecopedagogy and citizenship in the age of globalisation: Connections between environmental and global citizenship education to save the planet. European Journal of Education, 50(3), 280–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12138

Misiaszek, G. W. (2018). Educating the global environmental citizen: Understanding ecopedagogy in local and global contexts. Routledge.

Misiaszek, G. W. (2019). The end of the cognitive empire: The coming of age of epistemologies of the South by Boaventura de Sousa Santos. Comparative Education Review, 63(3), 452–454. https://doi.org/10.1086/704137

Misiaszek, G. W. (2020a). Countering post-truths through ecopedagogical literacies: Teaching to critically read “development” and “sustainable development.” Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(7), 747–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1680362

Misiaszek, G. W. (2020b). COVID-19 foreshadowing Earth’s environmental tipping point: Education’s transformation needed to avoid the ledge. Educational Philosophy and Theory, Add (with “Reimagining the new pedagogical possibilities for universities post-Covid-19” by Peters, Michael A.; Rizvi, Fazal; McCulloch, Gary; Gibbs, Paul; Gorur, Radhika; Hong, Moon Hwang; Yoonjung, Zipin; Lew, Brennan, Marie; Robertson, Susan; Quay, John; Malbon, Justin; Taglietti, Danilo; Barnett, Ronald; Chengbing, Wang; McLaren, Peter; Apple, Rima; Papastephanou, Marianna; Burbules, Nick; Jackson, Liz; Jalote, Pankaj; Kalantzis, Mary; Cope, Bill; Fataar, Aslam; Conroy, James; Misiaszek, Greg William; Biesta, Gert; Jandrić, Petar; Choo, Susanne; Apple, Michael; Stone, Lynda; Tierney, Rob; Tesar, Marek; Besley, Tina & Misiaszek, Lauren), 31–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1777655

Misiaszek, G. W. (2020c). Ecopedagogy: Critical environmental teaching for planetary justice and global sustainable development. Bloomsbury.

Misiaszek, G. W. (2020d). Ecopedagogy: Teaching critical literacies of ‘development’, ‘sustainability’, and ‘sustainable development.’ Teaching in Higher Education, 25(5), 615–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1586668

Misiaszek, G. W. (2020e). Locating and diversifying modernity: Deconstructing knowledges to counter development for a few. In M. A. Peters, T. Besley, P. Jandrić, & X. Zhu (Eds.), Knowledge socialism: The rise of peer production: Collegiality, collaboration, and collective intelligence (pp. 253–276). Springer Nature.

Misiaszek, G. W. (2020f). Will we learn from COVID-19? Ecopedagogical calling (un)heard. Knowledge Cultures, 8(3), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.22381/KC8320204

Misiaszek, G. W., & Torres, C. A. (2019). Ecopedagogy: The missing chapter of pedagogy of the oppressed. In C. A. Torres (Ed.), Wiley handbook of Paulo Freire (pp. 463–488). Wiley-Blackwell.

Pongratz, L. (2005). Critical theory and pedagogy: Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s contemporary significance for a critical pedagogy. In G. Fischman, P. McLaren, H. Sunker, & C. Lankshear (Eds.), Critical theories, radical pedagogies, and global conflicts (pp. 154–163). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Postma, D. W. (2006). Why care for nature? In search of an ethical framework for environmental responsibility and education. Springer.

Said, E. W. (1979). Orientalism. Vintage Books.

Santos, B. d. S. (2007). Beyond abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledges. Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 30(1), 45–89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40241677

Santos, B. d. S. (2016). Epistemologies of the South and the future. From the European South: A Transdisciplinary Journal of Postcolonial Humanities, 1, 17–29.

Santos, B. d. S. (2018). The end of the cognitive empire: The coming of age of epistemologies of the South. Duke University Press.

Singh, N. M. (2019). Environmental justice, degrowth and post-capitalist futures. Ecological Economics, 163, 138–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.05.014

Streeck, W., Calhoun, C., Toynbee, P., & Etzioni, A. (2016). Does capitalism have a future? Socio-Economic Review, 14(1), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwv037

Torres, C. A. (2009). Chapter 1: Globalizations and education: Collected essays on class, race, gender, and the state. Teachers College Press.

Warren, K. J. (2000). Ecofeminist philosophy: A Western perspective on what it is and why it matters. Rowman & Littlefield Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Misiaszek, G.W. (2022). Ecopedagogy: Critical Environmental Pedagogies to Disrupt Falsely Touted Sustainable Development. In: Abdi, A.A., Misiaszek, G.W. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook on Critical Theories of Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86343-2_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86343-2_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86342-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86343-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)