Abstract

Inherently political, environmental destruction benefits some while negatively affecting many others. The most crucial environmental concern is learning to critically and dialectically determine the connections between environmental degradation and social injustices (socio-environmental issues). Such knowledge allows for critical understanding of the deeper roots of the causes and effects of environmental devastation. Connections between the environmental and the social are often hidden by those who, in many cases, benefit from specific environmental devastation.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Inherently political, environmental destruction benefits some while negatively affecting many others. The most crucial environmental concern is learning to critically and dialectically determine the connections between environmental degradation and social injustices (socio-environmental issues). Such knowledge allows for critical understanding of the deeper roots of the causes and effects of environmental devastation. Connections between the environmental and the social are often hidden by those who, in many cases, benefit from specific environmental devastation. Although biocentric viewFootnote 1 is essential to determine the effects of environmental devastation, anthropocentric perspectives are necessary for determining political reasons. In addition, socio-environmental factors tend to be ignored because environmental devastation is often tangibly and/or ideologically removed from social conflicts, often intentionally, in terms of polity, time, location and hegemony. Ecopedagogy, defined as progressive environmental education which critically and dialectically deconstructs how social conflicts and environmental devastation are connected, allows for a deeper understanding from which possible solutions can emerge.

This chapter is constructed within a progressive sociology of education framework in which the ‘effectiveness’ of education is a result of politics outside of the classroom rather than teaching dynamics inside the classroom which, in turn, is inherently guided by the outside politics (Teodoro and Torres 2007). In this chapter, ecopedagogy is viewed through this framework by focusing on society’s effects upon education rather than pragmatic classroom techniques. First will be determined some of the gaps in traditional environmental education models for the critical, transformative learning necessary to understand and then change socio-environmental ills. Next, the need for comparative education approaches to teach and research the teaching of ecopedagogy, due to their interdisciplinary nature and dialectical methods for viewing the local and global, will be discussed. Then, the author’s own adult non-formal and informal ecopedagogy research in North and South America will provide some examples of these approaches. Finally, the conclusion will discuss the essential tenets of ecopedagogy practice and research inside and outside the framework of comparative education. It is important to note that although ecopedagogy is this chapter’s focus, the lessons learnt are translational to pedagogy practice and research on other topics which focus on transformation towards increased social justice.

Comparing Ecopedagogy to Shallow Environmental Education

… [it is] well known to all that environmental degradation generates human conflicts.

Moacir Gadotti, Ph.D., an author of the United Nations Earth Charter and Director and Co-Founder of the Paulo Freire Institute, São Paulo, Brazil (p. 43; 2008)

The well-being of a society’s environment defines the society nature and biophysical dynamics that define social dynamics (Zimmerer and Bassett 2003). However, the connections between humans and natureFootnote 2 are often ignored in many environmental education models (Commoner 1971; Gadotti 2008). Though environmental issues do not exist within disciplinary vacuums, many environmental education models are taught within mono-disciplinary models. Social sciences and humanities disciplines are ignored in environmental education or, at best, separated from ones within the hard science disciplines. Shallow environmental education models ignore the social complexities of environmental issues as well as possible transformations of current social systems and ideologies. Philosopher and environmental activist Arne Naess defined shallow ecology as one that develops environmental solutions within current social, economic and political systems, as opposed to deep ecology, which seeks more complete solutions through revolutionary change of these systems (Somma 2006). Shallow models are often fatalistic by limiting knowledge development within current systems. Assimilation towards current societal systems rather than transformation of these systems limits solutions within current systems of oppression.

Ecopedagogy, a deep alternative to shallow models, focuses on ending/decreasing social oppressions by critically learning how and why environmental problems are both the causes and effects of social conflicts.Footnote 3 Ecopedagogy, by definition, is critical and dialectical (Kahn 2010). Ecopedagogy allows for individual and social transformation by critically questioning what is being taught and why (Freire 1970, 2005a; Mezirow 1991, 2000). Critical, horizontal dialogue is essential for ecopedagogies to democratically construct possible alternatives to oppressive systems, a process that moves towards utopian social justice teaching models (Gadotti 2008, 2009). Student(s) and teacher(s) teach and learn together to determine the results of and incentives for environmental devastation.Footnote 4

People cannot care about socio-environmental issues if they are not taught their causes and resulting negative effects (Postma 2006). Ecopedagogy allows for the unveiling of complex social structures to uncover the politically hidden reasons for and effects of environmental devastation. It is argued that more effective solutions emerge from comparative approaches because they provide a deeper understanding of the complexities constructing socio-environmental problems. In contrast, shallow models aid in sustaining oppression by diverting focus away from dominant political reason and focusing on solutions that do not counter hegemony. Possible solutions develop by revealing systems of oppression caused by environmental devastation and then determining what transformation must take place. Solutions emerge from critically analysing social aspects of environmental issues and determining the necessary changes towards possible utopias (Freire 1998a, 2004; Freire and Freire 1997).

Comparative Approaches to Ecopedagogy

In my view, no other disciplinary or professional field [comparative education] has such a broad, interconnected vantage point from which to view the dilemmas of our time. (Klees 2008)

An ecopedagogue must be the opposite of Max Weber’s definition of a narrowly focused ‘specialist without spirit’. Understanding the complex interconnections between environmental devastation and social injustices requires interdisciplinary learning and analysis from various perspectives outside of one’s own to develop effective pedagogies – this is the essence of the field of comparative educationFootnote 5 (Crossley and Watson 2003; Foster 1998). Comparative educators focus on ‘…explaining how and why education relates to the social factors and forces that form its context’ (Epstein 1992, p. 409). Within the realm of ecopedagogy, methods of comparative education allow for revealing the often hidden connections between education, mis-education and non-education of socio-environmental issues due to politics. Ecopedagogy’s challenges reside in the complex relationships between the environmental and the social: environmental problems are often international in scopeFootnote 6; negative effects are often insignificant or dormant for very long time periodsFootnote 7 and many negative effects are difficult to witness through an anthropocentric lens.Footnote 8 Comparative education gives the advantage of being ‘literally constituted by border crossings, and comparative educators, by necessity, roam[ing] far beyond education’; in essence, giving context within specializations (Klees 2008, p. 309).

Processes of globalization can further hamper the identification of the source(s) of socio-environmental problems since dominant ideologies often tend to normalize the idea that environmental devastation is necessary for human survival and ideals of progress that, in turn, increase livelihood. In the same respect that the local is affected by distant politics within processes of globalization (Giddens 1990, 1999), environmental ills often do not respect geo-political borders – resulting in social conflict far away from the source. Since globalization influences the formal, informal and non-formal educators that develop socio-environmental knowledge, it is essential that pedagogies and their research cross geopolitical borders to understand the dynamics of local and global politics. Holistic views of politics, society and education are necessary from both micro and macro perspectives (Bray et al. 2007; Bray and Thomas 1995; Masemann 2007; Welch 2007). Brazilian ecopedagogue and Freirean scholar Moacir Gadotti stressed that ‘fixing one room in a house is not enough… [one must] include all rooms of the house in its different dimensions: economic, social, cultural, environmental, etc’ (2009, p. 30).

Globalization might be irreversible, but its processes are transformable (Gadotti 2009; Carlos Torres 2007). To develop a broader, macro view of ecopedagogy, comparative education delves into both differences and similarities, developing rich dialogue and curiosities to learn from, collectively and individually (Morrow and Torres 2002). Effective research develops initially out of curiosities which can be developed more rigorously into research: ‘…human curiosity, as a phenomenon present to all vital experience, is in a permanent process of social and historical construction and reconstruction’ (Freire 1998a, p. 37; Morrow and Torres 2002). Paulo Freire defined the following two types of curiosities: ingenuous curiosity which ‘characterizes “common sense” knowing. It is knowledge extracted from pure experience’; and epistemological curiosity, which ‘becomes more methodologically rigorous, progresses from ingenuity to epistemological curiosity…’ (1998a, p. 35; Morrow and Torres 2002). Processes of globalization prioritize this need with the nation-state unit of analysis being redefined by globalization, resulting in the need for critical education (Welch 2007, p. 30). Critically viewing environmental and social processes from both micro and macro perspectives is required to develop multi-layered methods of research which use and build upon the richness of other ecopedagogy programs, by determining their evolution (King 2000; CA Torres 1995).

Comparative education methodologies allow for critical comparisons between ecopedagogy programs, a process essential for determining which methods to lend and borrow (Altbach 1998; Arnove 2007; Steiner-Khamasi 1998, 2004). An effective ecopedagogy program in one area cannot be simply cloned for another area because programs are contextual and thus unique (Noah and Eckstein 1998; Watson 1999). However, an interdisciplinary, comparative approach allows for borrowing and lending that aids the construction of ecopedagogies developed with similar, but not identical, environmental and social characteristics, problems, questions and solutions. Global educational trends must be transformed and modified dialectically to develop programs and policies which meet needs for both national and local spheres (Arnove and Torres 2003; Rui 2007). Methods of comparative education utilized in ecopedagogy research allow for critical comparison of re-occurring themes and characteristics, measurement of translational results for effective praxis to emerge, development of problem-solving skills and development of effective ecopedagogical tools and curricula based on praxis.Footnote 9

A Horizontal, Comparative and Interdisciplinary Approach Towards Defining Effective Ecopedagogy

The following approach was constructed from qualitative, comparative education research of 35 progressive adult environmental informal and non-formal educators (mostly social/environmental movement leaders) in Buenos Aires and Cordoba, Argentina; São Paulo, Brazil and Appalachia, USA. The overall research question was: How do adult ecopedagogy educators define effective characteristics for ecopedagogy programs within these regions? Subset questions included the following: (1) What pedagogical tools do ecopedagogy educators utilize to develop critical thought processes of the interconnections between environmental degradation and social justice? (2) How do ecopedagogy educators determine successful ecopedagogy programs? and (3) What are ecopedagogy educators’ perceptions of the effects of processes of globalization on ecopedagogy? The research compared and contrasted the vertical relationships between The North and The South, within regions, nation-states and communities to critically determine oppressor/oppressed relationships. The constructed theoretical model emerged from the research participants’ voices. The resulting ecopedagogy developed within the theoretical underpinnings from the participants through horizontal discussions rather than through vertical interview methods with authority placed upon the interviewer. In other words, the interdisciplinary nature of the theoretical framework was developed from the participant educators themselves.

Although there always exists a vertical positionality between researcher and research participant, the interviews were as loosely structured as possible to encourage horizontal dialogue. Discussion topics were determined mostly by the participants, outside of two questions which, for most interviews, were addressed preemptively by the participants.Footnote 10 There existed no pre-determined list of interview questions. Interviews began with a general question asking for the participant’s thoughts on, experiences with and background in environmental education. From these initial remarks, participants then guided the discussion and self-selected topics of importance.

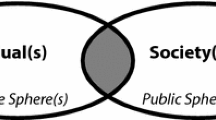

This bottom-up approach to interviews is a reinvention of Freirean pedagogy. The participants, rather than the researcher, dictated the path of research, thus avoiding a highly structured format prone to limiting participants’ interests, context and space. As in Freirean pedagogy, this interview process is founded on ‘…love, humanity, and faith, dialogue becomes a horizontal relationship of which mutual trust between the dialoguers is the logical consequence’ (Freire 2005b, p. 91). Research methods are based on respect for the knowledge of participants. Participant knowledge and curiosities are considered essential to the definition of the research and its conclusions. If information is gathered without regard for the participant(s)’ voice(s), the process would turn data into something that would be ultimately flawed, by being consciously or unconsciously shaped by the researcher(s). If information is gathered by ignoring (or silencing) the voice of the people who stated it, the processes of the research itself as an entirety would be skewed towards the single perspective of the researcher. This research method allows for a better analysis of the topic selections because they are determined by participants; thus, what they identify as important in their discussion of ecopedagogy is what becomes significant. Freirean pedagogy emerged as the foundation of environmental education and research with the need for horizontal and democratic dialogue to read and re-read complex and often hidden links between environmental and social injustices. Other theoretical lenses include the following: theories of globalization and neocolonialism; critical race theories; theories of feminism; critical media cultural theories and theories of sustainable development. Individual theories were found not to be isolated but interconnected with each other. The connections between the topics that developed into theories were complex and depended on multidisciplinary understanding. The research found that theoretical themes were not discussed in isolation but within complex theoretical webs within one another. Figure 26.1 illustrates the theories utilized in the ecopedagogical research conducted. The following description of each theoretical component emerged from what the participants believed to be necessary for effective ecopedagogy.

Freirean Pedagogy: Reinvented as Freirean Ecopedagogy

Paulo Freire’s last book, incomplete on account of his sudden death, was to be focused on the topic of ecopedagogy. Some of Freire’s ecopedagogical work was included in his book Pedagogy of Indignation, published after his death.

I do not believe in loving among women and men, among human beings, if we do not become capable of loving the world. Ecology has gained tremendous importance at the end of this century. It must be present in any educational practice of a radical, critical, and liberating nature. (Freire 2004, p. 25)

A reinventionFootnote 11 of Freirean pedagogy towards a Freirean ecopedagogy focuses on raising consciousness (conscientização) about societal oppression caused by environmental degradation. Environmental problems must be deconstructed and re-constructed within social justice frameworks, through critical dialogue to enhance ‘reading of the world’ through various knowledges and theoretical frameworks.

A central question for ecopedagogy is: Who is benefiting from destruction and who/what is negatively affected? To obtain Weber’s ideal, environmental interest actions must evolve out of ecopedagogy practice and research by viewing environment holistically outside of instrumental terms involving benefit analysis, seeking intrinsic value from the whole, rather than looking at how to utilize parts for oneself. Participants in this study stressed the need for ecopedagogy to challenge existing knowledge concerning hegemony-constructed solutions, and read environmental problems within a larger macro societal framework in order to become conscious of oppressive sources that lead to environmental degradation. Freire described how ‘[peasants were] engendered [with] their unauthentic view of the world. Using their dependence to create still greater dependence is an oppressor tactic’(2005b, p. 66). Without questioning the current social systems which oppresses those who are negatively affected by those who benefit, environmental destruction is viewed as negative but necessary and beneficiary. Freirean pedagogy calls for horizontal and democratic discussions between teacher(s)/student(s) and researcher(s)/participant(s) to determine how learning and curiosities (research catalysts) will develop (Freire 1998b, 2005b; Morrow and Torres 2002; O’Cadiz et al. 1998). Freire stressed the need for the oppressed to expand their own thematic universe – a frame of reference in which individuals view themselves within society. Educational and research spaces must provide acceptance for critical discourse so that participants may determine oppressions and develop solutions to end them.

Freirean ecopedagogy stresses a radical discourse that is critical and empowering, rather than a technical discourse that seeks change through co-operation without systematic change; nor a liberal discourse that promotes individual growth rather than collective growthFootnote 12 (Whelan 2003). Freirean praxis allows for people to theorize, dream and dialogue about a better world, and then determine actions needed to transform towards it. Freire expressed that education is necessary for social progress because ‘…human activity consists of action and reflection: it is praxis; it is transformation of the world’ (Freire 2005b, p. 125). Dialogue needs to be full of love and understanding, so there can be progress to ‘recreate the world’ for the better, with actions defined by dialogue’s conclusions.

Theories of Globalization: Proliferation of Neoliberalism and Neocolonialism

Globalization is a complex, multi-dimensional phenomenon with contrasting positive and negative effects on education focused on social justice. Analysis of globalization depends upon context, purpose and who is using this term (Kellner 1998). Two globalization typologies are ‘globalization from above’, which promotes neoliberalism and sustains hegemony, and ‘globalization from below’, which ‘…use[s] its institutions and instruments to further democratization and social justice’ (Kellner 1999a, p. 301). An example of globalization from below is increasing awareness and participation in environmentalism, democratic governing and human rights by increasing communication and oversight (Kellner 1998). Globalization from above normalizes neoliberal ideology that views environmental ills as unfortunate but necessary to increase livelihood. These oppressive processes devalue environmental and social welfare, by determining all decisions according to neoliberal goals of increasing monetary profit and determining all actions to achieve this end (Chomsky and Macedo 2000; Kellner 1998; Stromquist 2002). Freire believed that globalization created an unsustainable pressure from distant but economically and politically influential Western markets that have neoliberal interests in high production, high development and low cost.

Ecopedagogy was found to need to critically deconstruct globalization through many related theories such as oppressive neoliberalism and neocolonialism. Comparing socio-environmental globalization processes was seen as essential to determine oppressive from empowering processes. In the past, imperialistic nations had colonies around the world which fulfilled natural resource needs that were unattainable on their own lands. Critically and dialectally deconstructing the local and global was considered necessary to understand the dynamics of economic neocolonialism in which more economically developed nation-states construct a global society in which less economically developed nations yield to pressures to fulfil demands. Globalization that sustains hegemony allows more economically developed nation-states to purchase natural resources at excessively low prices, without regard for current and long-term ills caused by producing or removing these natural resources from economically under-developed nation-states. To maximize profit, natural resources are removed, processed and/or altered (i.e. into fuel) without regard for the resulting oppression of environments and societies. Progressive pedagogies, such as ecopedagogy, must bring about the ‘decolonizing of the mind’ by bringing forth and critically analysing normative, false knowledge from a colonized education (Dei 2006). In addition, participants stressed that ecopedagogy must be a utopian pedagogy that strives for transformation rather than globalization processes which promote the belief that there are no viable alternatives to neoliberalism. Persons discussing alternatives to current Western systems are viewed by many as ‘dinosaurs’ (Cole 2005; McLaren and Farahmandpur 2005). Radical and revolutionary pedagogies can aid students in seeking alternatives to current oppressive systems and transcending false consciousness by helping them realize that education indoctrinates citizens to alienate those who seek alternatives (Cole 2005; Giroux 2001). Ecopedagogy must be placed within an anti-colonial, historiographic framework that does not infer that indigenous peoples are foreigners on stolen, colonized land, and that whites were saviours of ‘savages’ (Kempt 2006). Colonial education and schooling, in general, shifts the benchmark of goodness from working within nature, to dominating it (Illich 1983).

Critical Race Theories – Ecoracism

Critical race theories were found to be extremely significant to understanding connections between negative environmental/ecological actions, social injustices and theories of whiteness. Racism sums up and symbolizes the fundamental relation between the colonialist and the colonized (Memmi 1991, pp. 69–70). Remnants from a colonial past provide education that instils white supremacy: viewing non-whites as inferior and justifying oppression and viewing actions of social justice as a form of white generosity rather than an intrinsic right (Dei 2006; Freire 2005b). The mark of the plural allows the destruction and exploitation of the environment, because nature is seen as non-holistic and wasted upon others which include the colonized. One important example is the Not in my Backyard (NIMBY) syndrome, which de-locates and re-locates environmental hazards to a low socio-economic, often non-white community, where citizens are too powerless to defend their own welfare within the courts and halls of government, and where community members are often so systematically desperate for employment that they agree to unacceptable levels of environmental and health hazards. Ecopedagogy must critically analyse neoliberal benefits stemming from poor environmental policies, ecoracism (e.g. cheap products; out-of-sight, out-of-mind environmental problems, etc.), and the seduction of whiteness for those who benefit (Yancy 2004).

Environmental problems originating from ecoracism are often due to ‘…ontological structure, a true immanence, a thing unable to be other than what it was born to be, a thing closed upon itself, locked into an ontological realm where things exist not “for-themselves” but “in-themselves”, waiting to be ordered by some external, subjugating, purposive (white) consciousness’ (Yancy 2004, p. 12). For example, NIMBY places environmental problems in non-white communities, due to the temptation for white communities to displace problems at hand, and their political power to do so. The NIMBY solution makes it difficult for the privileged not to choose actions that benefit them, much like the dilemma of whites not wanting to ‘unbecome’ white, because of benefits which have become normalized (Yancy 2004). Most whites would not define themselves as racists, but racism must be redefined according to anti-whiteness standards that dis-establish non-earned benefits according to skin color (Mills 2004). Ecopedagogy must critically analyse this discrepancy within ecoracism fuelled by a hegemonic white population.

Theories of Feminism – Ecofeminism

There are many theoretical constructs of ecofeminism but the framework of ecofeminism that emerged from this research ‘includes a systemic analysis of domination that specifically includes the oppression of women and environmental exploitation, and it advocates a synthesis of ecological feminist principles as guiding lights…’ (Lahar 1991, p. 29). Ecofeminism critically analyses ideologies that construct what are men, women and nature – ideologies that are mostly developed under the influences of dominance and oppression (Warren 2000). Dominance differs from oppression, because oppression is limited by degrees of choice. Nature does not have choices to be suppressed, but it can be unjustly abused (Warren 2000). This type of ecofeminism calls for a ‘“cognitive dissonance” to motivate a re-examination of one’s basic beliefs, values, attitudes and assumptions – one’s conceptual framework’ – to dismantle thought processes of superiority of humans over nature, and false vertical relationships between humans (Warren 2000, p. 56). Ecofeminism is not viewed as a solely binary analysis between feminist issues and environmentalism, but instead provides a framework for critically re-thinking this relationship as a dominant foundation for fighting against all forms of domination (Lahar 1991; Warren 2000). This concept is similar to Paulo Freire’s theories of conscientização (Ress 2006).

The terms feminism and ecofeminism were only directly stated by a few participants, but the concepts that develop the foundation of the theories were significantly represented in the research. The representation of the philosophy of ecofeminism stressed the need to respect, without exception, theories of feminism, indigenous knowledge and environmental well-being – which is model ecofeminism, according to Karen Warren (2000). Warren describes the context of ecofeminism as being a ‘quilt’ in which patches are different when viewed individually, but become holistic when all types of ecofeminism are sewn together. This philosophy can also be described as a ‘fruit bowl’ in which praxis of ecofeminism represents different typologies of fruit, but remains fruit in a bowl as a whole (Warren 2000). Warren stresses that ecofeminism does not look at ecology only through analyses of gender, but also as a starting point for thought and praxis to critique dominance and oppression (Warren 2000).

Critical Media Culture Theories

The research found that the media’s large role in influencing the ways we interpret reality makes it essential to critically question the politics that influence the construction of media, and thus the construction of prevalent socio-environmental ideology. Critical media culture analysis allows for systematic uncovering of alternative truths, realities outside the normalized and hegemonic hidden curricula that form persons’ thematic universes, as defined by Freire (Freire 2005b). Analysis of the media must be multi-perspective, so that these lenses can be used to de-construct and then re-construct its messages, avoiding use of only a singular theory to delve into the politics of what representations and messages are being developed for our eyes to see and for our ears to hear (Durham and Kellner 2006; Kellner 1995b). Much like contrasting processes of globalization, the media is a contested terrain which can be both oppressive and empowering with regard to social justice. Media from below can be ‘…both critical of corporate and mainstream forms, as well as to support technologies that advocate re-construction of technologies to further projects that advance progressive social and political struggle‘ (Kahn and Kellner 2006). Dominant media has the ability to counter rather than sustain hegemony; however, politics of media often hide hegemonic effects. Global communication technologies must be evaluated as to how they can be used to spread messages for the sake of attaining a purer democracy and more effective social movements, and to assist in political struggles of all persons (Best and Kellner 2001; Kahn and Kellner 2003; Kellner 1995a, 1997, 1999b).

The media is a powerful tool and an influential public pedagogy which could develop ideologies insisting that environmental stewardship is necessary and beneficial on many levels or it could express the opposite view that environmental devastation is unfortunate but necessary, and assist this belief by obscuring connections between environmental and social problems. Participants believed that ecopedagogy must ask how the media portrays environmental issues within socio-environmental frameworks.

Sustainable Development and Livelihoods

The research indicated that the ways in which sustainable development is framed and how it relates to pluralistically defined livelihood Footnote 13 is essential to understanding socio-environmental issues. Sustainable development is seen as necessary to provide for an improved livelihood that allows for improved economic status, security and dignified lives, without compromising our planet’s sustainability for current and future generations (Roseland and Soots 2007). All participants discussed how sustainable development has overwhelmingly focused on economic development, rather than ‘…bottom-up, participatory, holistic, and process-based development initiatives’ (Mahadevia 2001, p. 243). Globalization from above has altered the definition of development worldwide, defining progressive development as what benefits the global economy. Benefiting the global economy is often measured by what benefits and sustains hegemony, rather than what is good on the local, as well as global scale.

Similar to environmental education, which can be deep or shallow, education for sustainable development can be of either model. Some participants believed that development might be better defined as maldevelopment for the masses (Gadotti 2009; O’Rourke 2004; Pieterse 2006; Zimmerer and Bassett 2003). Sustainable development is often narrowly viewed through limited anthropocentric and neoliberal lenses, placing environmentalism within a rubric measuring economic gain and personal pleasures (Bell 2004; Bolscho 1998; Jickling 1994; Postma 2006; Sauvé 1998, 2002). Many deep environmentalists stress that sustainable development is overwhelmingly a concept that promotes neocolonialism, by grouping the development of economically under-developed nation-states according to a framework generated by hegemonic nation-states (Hesselink et al. 2000; Postma 2006). Shallow sustainable development framed within current neoliberal goals results in sustaining and often increasing hegemony (Hoardoy et al. 1992; Mahadevia 2001).

Research indicated that the use of hard sciences was often an oppressive force in defining sustainable development due to how they were used by those who commit environmental ills. Although stressed by the dominant as unquestionably objective, participants stressed the need for ecopedagogy to critically question the politics, access and definition of Western sciences. As development is often measured economically, shallow sustainable education and research models use a positivistic view. Processes of globalization from above have promoted an ideology that values Western, ‘hard’ Sciences (denoted by Sandra Harding with a capital ‘S’) as the only method to view nature, and to give objective views of its unchanging ‘laws’ (Bonnett 2003; Elliot 1992; Harding 1991, 1998, 2006). Science views observation and manipulation of nature not as subjective, but instead as an objective method towards observing, stating and manipulating what is reality. Within this framework, there develops a binary between ‘good’ Science and all other types of sciences (denoted by a lowercase ‘s’). Harding stresses that Science is defined by methods, analyses, outcomes and final products that are racist, without requiring the scientists who constructed them to have racist intentions (2006). She also notes that the hegemonic relationship between science and ‘development has brought de-development and maldevelopment to the “have-nots”, and economic benefits to the investing classes of the Global North’ (2006, p. 42). Rather than Science helping the oppressed by creating solutions to end environmental degradation, neocolonial oppression is furthered by destroying their environment, taking their natural resources, and exploiting their labour to maintain and intensify hegemony (S. Harding 2006). Science conducted inside the laboratory has promoted systematic ignorance, by eliminating any accountability for environmental and/or societal harms produced by their ‘discoveries’ (S. Harding 2006; Hutchins 1995). Science is seen as having the sole mission to create what is possible, without providing a socio-ecological context. Lacking critiques of social issues caused by Sciences forms a perfect platform for exploiting the environment. This system stresses that after-effects caused by Science are not any cause for concern.

However, the Sciences are also a contested terrain, with participants discussing how the Sciences have increased consciousness of environmental problems central to organized environmental movements, allowing for the definition of salient issues among public and political leaders. Held has argued that s/Science has brought to light environmental problems which would have been otherwise invisible to the public (Haas 1990; Held 1999). Rather than looking for answers to problems between society and the environment in a multi-disciplinary approach, many participants believed that Science looks only to inventing new technologies to solve problems. All the participants who discussed s/Sciences to define sustainable development stressed the need for this multi-disciplinary approach to critically view Sciences within social spheres.

Conclusion

[Environmental pedagogies must] ‘see the importance of translating this concept [ecopedagogy] into different realities and different pedagogies, such as Paulo Freire’s pedagogy, which starts from reading the word, from respecting every person’s context, and which offers an emancipating and dialogical methodology.’ (Gadotti 2009, p. 86)

The research indicated overwhelmingly that critical and dialectical discussions were necessary for effective adult environmental education. The diversity of topics the participants discussed and the interconnections among them strongly suggested the need for an interdisciplinary approach to ecopedagogy. ‘Comparative’, ‘multi-perspective’ and ‘multi-disciplinary’ are all essential characteristics of ecopedagogy, as well as essential characteristics for comparative education. Knowledge of environmental devastation’s causes and effects cannot be simplified towards a single framework, come from a single perspective and/or be compartmentalized within a single discipline. Problem-solving constructed from shallow environmental or socio-environmental knowledge does not have the depth to develop meaningful, sustaining praxis. Lack of depth in problem-solving results in simple, positivistic conclusions ultimately fails to comprehend the complexities of the societies in which the solutions must take place. In addition, shallow approaches ignore non-anthropocentric frameworks and social issues which negatively affect all that is non-human. The inadequacies of shallow environmental education practices and research help to sustain socio-environmental ills by focusing on solutions which further obscure knowledge of ‘inconvenient’ society-environment issues which, in turn, sustains hegemony (Giroux 2001). Difficult and inconvenient socio-environmental questions are not asked due to ignorance – often politically motivated lack of knowledge.

Dialectical approaches allow for the viewing of socio-environmental problems through multiple theoretical lenses and perspectives. These approaches comprise the essence of critical theory which, by its nature, opposes closed philosophical systems, in order to view the world according to perspectives which are ‘open-ended, probing, [and with an] unfinished quality’ (Jay 1996, p. 41). Comparative education’s interdisciplinary nature (Crossley 2000) allows for such dialectical processes. As processes of globalization dialectically affect, in a give-and-take fashion, the global, national, and local spheres (Arnove 2007), comparative education scholars need to view the education of socio-environmental issues from various theoretical lenses and individual perspectives to develop effective ecopedagogy programs, relevant research and well-developed praxis.

The ecopedagogy practice and research completed provide only one example and by no means account for all of the complexities of environmental and social issues. The effectiveness of these and other approaches falls upon determining the reasons of their construction and then critically determining the strengths of an approach, the factors which were not being sufficiently accounted for, and ways to compensate for the weaknesses.

Entirely ending nature’s destruction and the accompanying social injustices is unlikely to become a reality, but such a utopian ideal needs to be the overarching goal for any pedagogy (Teodoro and Torres 2007). Without the ability to dream of utopia, education cannot be transformative and fatalism will override the ability to comprehend any alternatives (Freire 1998a). Critical, horizontal and democratic dialogue is the most important factor towards reaching this horizon to develop transformative understandings resulting in action. Freirean pedagogy is central to this approach because dialogue, as defined by Freire, must be full of truths not defined by dominant ideologies, but by all participants (including teachers, students, researchers and research participants).

Solutions to socio-environmental ills are not easily answered because of the diverse continuum of those who benefit from and are negatively affected by these ills; however, critical and dialectical dialogue allows incremental understanding of these issues from various perspectives, local–global spheres, situations and disciplines. It is important to remember that beneficiaries of environmental destruction are not always massive hegemonic agents aiming towards economic profiteering but are often communities and individuals who act for the purpose of acquiring life’s basics for survival and increasing livelihood as they define it. For example, a mother might try to provide for her family by deforesting a small part of the Amazon, to sell the wood, and to open up land to grow agriculture and/or graze animals. Such environmentally devastative actions are inherently more difficult to argue against than actions taken for the purpose of transnational corporate profit. Ecopedagogy and its research must be constructed from horizontal dialogue from everyone (teachers, students, researchers, research participants, etc.) to collectively determine what factors are needed to be taught and learned. The theoretical foundation in ecopedagogical practice and research must emerge from all voices.

Notes

- 1.

A biocentric view considers holistically, all human and non-human, effects of environmental devastation.

- 2.

Although humans are part of nature, nature here is defined as everything else on Earth other than humans.

- 3.

There are numerous definitions of ecopedagogy.

- 4.

Education in all spheres (formal, informal, and non-formal (public pedagogy)) is analysed.

- 5.

International education has the same characteristics with the only difference being that comparisons are between two or more nation-states.

- 6.

For example, air pollution does not only affect the area near polluting sources but pollutants are carried with wind without regard of local, national or international borders.

- 7.

For example, it often takes several generations for ill effects of toxic waste disposal to become apparent due to long period of container degradation, or slow seepage to surface.

- 8.

For example, species extinction is often not directly negatively affected by humans but there is an intrinsic right for a species to not become extinct.

- 9.

Praxis here is Freirean defined as theoretical reflection to determine action.

- 10.

The two questions were the following: (1) How do you define sustainable development; and (2) What do you do when someone says ‘Environmental devastation is bad, but its actions determine my, my family’s, and/or my community’s livelihood?’.

- 11.

Reinvention of Freire’s work is a key tenet towards how he defined praxis. He believed that coding and re-coding of theory was essential towards theory becoming relevant.

- 12.

Knowledge must inspire action towards reversal and prevention of environmental problems, beyond concern for their own self-interests. Learning and action must occur beyond liberal sphere, which Weber would define as ideal action behaviour (or value rational behaviour) (McIntosh 1977).

- 13.

Livelihood has many definitions. According to this chapter “A livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets (both natural and social) and activities required for a means of living; a livelihood” (Chambers and Conway 1992, p. 7). Livelihood goes beyond alleviation of poverty, to include improved local access and control over necessary assets that help lessen one’s vulnerability to environmental shocks and stresses (Roseland and Soots 2007).

References

Altbach, P. G. (1998). The university as center and periphery. In Comparative higher education: Knowledge, the university, and development (pp. 19–36). Greenwich: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Arnove, R. F. (2007). Introduction: Reframing comparative education: The dialectic of the global and the local. In R. F. Arnove & C. A. Torres (Eds.), Comparative education: The dialectic of the global and the local (3rd ed., pp. 1–20). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Arnove, R. F., & Torres, C. A. (2003). Comparative education: The dialectic of the global and the local (2nd ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bell, D. R. (2004). Creating green citizens? Political liberalism and environmental education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 38(1), 37–54.

Best, S., & Kellner, D. (2001). The postmodern adventure: science, technology, and cultural studies at the Third Millennium. New York: Guilford Press.

Bolscho, D. (1998). Nachhaltigkeit- (k)ein Leitbild fur Umweltbildung. In A. Beyer (Ed.), Nachhaltigkeit and Umweltbildung (pp. 163–177). Hamburg: Kramer.

Bonnett, M. (2003). Retrieving nature: Education for a post-humanist age. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 37(4), 551–730.

Bray, M., & Thomas, R. M. (1995). Levels of comparison in educational studies: Different insights from different literatures and the value of multilevel analyses. Harvard Educational Review, 65(3), 472–490.

Bray, M., Adamson, B., & Mason, M. (2007). Comparative education research: Approaches and methods. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre Springer.

Chambers, R., & Conway, G. (1992). Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Chomsky, N., & Macedo, D. P. (2000). Chomsky on miseducation. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Cole, M. (2005). New labor, globalizism, and social justice: The role of education. In G. E. Fischman, P. McLaren, H. Sunker & C. Lankshear (Eds.), Critical theories, radical pedagogies, and global conflicts (pp. 3–22). Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Commoner, B. (1971). The closing circle: Nature, man, and technology (1st ed.). New York: Knopf.

Crossley, M. (2000). Bridging cultures and traditions in the reconceptualisation of comparative and international education. Comparative Education, 36(3), 319–332.

Crossley, M., & Watson, K. (2003). Comparative and international research in education: Globalisation, context and difference. London New York: Routledge/Falmer.

Dei, G. J. S. (2006). Introduction: Mapping the terrain – Towards a new politics of resistance. In G. J. S. Dei & A. Kempf (Eds.), Anti-colonialism and education: The politics of resistance (p. 313). Rotterdam: Sense.

Durham, M. G., & Kellner, D. (2006). Media and cultural studies: Keyworks (Rev. ed.). Malden: Blackwell.

Elliot, R. (1992). Intrinsic value, environmental obligation and naturalness. The Monist, 75(2), 138.

Epstein, E. H. (1992). Editorial. Comparative Education Review, 36(4), 409–416.

Foster, P. (1998). In H. J. Noah & M. A. Eckstein (Eds.) Doing comparative education: Three decades of collaboration. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, Comparative Education Research Centre.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Freire, P. (2004). Pedagogy of indignation. Boulder: Paradigm.

Freire, P. (2005a). Education for critical consciousness. London/New York: Continuum.

Freire, P. (2005b). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Freire, P., & Freire, A. M. A. (1997). Pedagogy of the heart. New York: Continuum.

Gadotti, M. (2008). What we need to learn to save the planet. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 2(1), 21–30.

Gadotti, M. (2009). Education for sustainability: A contribution to the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. Saõ Paulo: Editora e Livraria Instituto Paulo Freire.

Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Giddens, A. (1999). Runaway world: How globalisation is reshaping our lives. London: Profile.

Giroux, H. A. (2001). Theory and resistance in education: towards a pedagogy for the opposition (Rev. and expanded ed.). Westport: Bergin & Garvey.

Haas, P. M. (1990). Saving the Mediterranean: The politics of international environmental cooperation. New York: Columbia University Press.

Harding, S. G. (1991). Whose science? Whose knowledge?: Thinking from women’s lives. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Harding, S. G. (1998). Is science multicultural?: Postcolonialisms, feminisms, and epistemologies. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Harding, S. (2006). Science and social inequality: Feminist and postcolonial issues. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Held, D. (1999). Global transformations: Politics, economics and culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hesselink, F., Kempen, P. P. v., & Wals, A. E. J. (2000). International union for conservation of nature and natural resources. Commission on education and communication. ESDebate: International debate on education for sustainable development. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN Commission on Education and Communication.

Hoardoy, J., Milton, D., & Satterthwaite, D. (1992). Environmental problems in third world. London: Earthscan.

Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Illich, I. (1983). Deschooling society (1st Harper Colophon ed.). New York: Harper Colophon.

Jay, M. (1996). The dialectical imagination: A history of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research, 1923–1950. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jickling, B. (1994). Why I don’t want my children to be educated for sustainable development. The Journal of Environmental Education, 23, 508.

Kahn, R. (2010). Critical pedagogy, ecoliteracy, and planetary crisis: The ecopedagogy movement (Vol. 359). New York: Peter Lang.

Kahn, R., & Kellner, D. (2003). Internet subcultures and oppostitional politics. In D. Muggleton & R. Weinzierl (Eds.), The post-subcultures reader (1st ed., pp. xii, 324 p.). Oxford; New York: Berg.

Kahn, R., & Kellner, D. M. (2006). Oppositional politics and the internet: A critical/reconstructive approach. In M. G. Durham & D. Kellner (Eds.), Media and cultural studies: Keyworks (Rev. ed., pp. 703–725). Malden: Blackwell.

Kellner, D. (1995a). Intellectuals and new technologies. Media Culture Society, 17(3), 427–448.

Kellner, D. (1995b). Media culture: Cultural studies, identity, and politics between the modern and the postmodern. London/New York: Routledge.

Kellner, D. (1997). Intellectuals, the new public spheres, and technopolitics. New Political Science, 41–42(Fall), 169–188.

Kellner, D. (1998). Globalization and the postmodern turn. Retrieved from http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/courses/ed253a/dk/GLOBPM.htm

Kellner, D. (1999a). Globalization and New Social Movements. In N. C. Burbules & C. A. Torres (Eds.), Globalization and education: Critical perspectives. New York: Routledge. 376 p.

Kellner, D. (1999b). Globalization and new social movements. In N. C. Burbules & C. A. Torres (Eds.), Globalization and education: Critical perspective (pp. 299–322.). New York: Routledge.

Kempt, A. (2006). Anti-colonial historiography: Interrogating colonial education. In G. J. S. Dei & A. Kempf (Eds.), Anti-colonialism and education: The politics of resistance (p. 313). Rotterdam: Sense.

King, E. (2000). A century of evolution in comparative studies. Comparative Education, 36(3), 267–277.

Klees, S. J. (2008). Reflections on theory, method, and practice in comparative and international education. Comparative Education Review, 52(3), 301–328.

Lahar, S. (1991). Ecofeminist theory and grassroots politics. Hypatia, 6(1), 28–45.

Mahadevia, D. (2001). Sustainable urban development in India: an inclusive perspective. Development in Practice, 11(2), 242–259.

Masemann, V. L. (2007). Culture and education. In R. F. Arnove & C. A. Torres (Eds.), Comparative education: The dialectic of the global and the local (3rd ed., pp. 101–116). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

McIntosh, D. (1977). The objective bases of Max Weber’s ideal types. History and Theory, 16(3), 265–279.

McLaren, P., & Farahmandpur, R. (2005). Teaching against global capitalism and the new imperialism: A critical pedagogy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Memmi, A. (1991). The colonizer and the colonized (Expandedth ed.). Boston: Beacon.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mills, C. W. (2004). Racial exploitation and the wages of whiteness. In G. Yancy (Ed.), What white looks like: African-American philosophers on the whiteness question (p. xvi). New York: Routledge. 279 p.

Morrow, R. A., & Torres, C. A. (2002). Reading Freire and Habermas. New York: Teachers College Press.

Noah, H. J., & Eckstein, M. A. (1998). Doing comparative education: Three decades of collaboration. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, Comparative Education Research Centre.

O’Cadiz, M. P., Wong, P., & Torres, C. A. (1998). Education and democracy: Paulo Freire, social movements, and educational reform in Säao Paulo. Boulder: Westview Press.

O’Rourke, D. (2004). Transition environments: Ecological and social challenges to post-socialist industrial development. In R. Peet & M. Watts (Eds.), Liberation ecologies: Environment, development, social movements (2nd ed., pp. 244–270). London/New York: Routledge.

Pieterse, J. N. (2006). Globalization as hybridization. In M. G. Durham & D. Kellner (Eds.), Media and cultural studies: Keyworks (Rev. ed., pp. 9–17). Malden: Blackwell.

Postma, D. W. (2006). Why care for nature?: In search of an ethical framework for environmental responsibility and education. New York: Springer.

Ress, M. J. (2006). Ecofeminism in Latin America. Maryknoll: Orbis Books.

Roseland, M., & Soots, L. (2007). Strengthening local economies. In L. Stark (Ed.), 2007 State of the world: Our urban future. New York: W.W Norton and Company.

Rui, Y. (2007). Comparing policies. In M. Bray, B. Adamson, & M. Mason (Eds.), Comparative education research: Approaches and methods (pp. 241–262). Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre Springer.

Sauvé, L. (1998). Environmental education between modernity and postmodernity: Searching for an integrating educational framework. In A. Jarnet, B. Jickling, L. Sauvé, A. Walls, & P. Clarkin (Eds.), The future of environmental education in a postmodern world? Yukon: University Press.

Sauvé, L. (2002). Environmental education: Possibilities and constraints. Connection: New England’s Journal of Higher Education and Economic Development, 17, 1–4.

Somma, M. (2006). Revolutionary environmentalism. In S. Best & A. J. Nocella (Eds.), Igniting a revolution: Voices in defense of the earth (pp. 37–46). Oakland, CA: AK Press.

Steiner-Khamasi, G. (1998). Transferring education, displacing reforms. In J. Schriewer (Ed.), Comparative studies. New York: Lang.

Steiner-Khamasi, G. (2004). The global politics of educational borrowing and lending. New York: Teachers College Press.

Stromquist, N. P. (2002). Education in a globalized world: The connectivity of economic power, technology, and knowledge. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

Teodoro, A., & Torres, C. (2007). Introduction: Critique and utopia in the sociology of education. In C. A. Torres & A. Teodoro (Eds.), Critique and utopia: New developments in the sociology of education in the twenty-first century (p. viii). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. 184 p.

Torres, C. (1995). The state and public education in Latin America. Comparative Education Review, 39(1), 1–27.

Torres, C. (2007). Paulo Freire, education, and transformation social justice learning. In C. A. Torres & A. Teodoro (Eds.), Critique and utopia: New developments in the sociology of education in the twenty-first century (p. viii). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. 184 p.

Warren, K. (2000). Ecofeminist philosophy: A western perspective on what it is and why it matters. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Watson, K. (1999). Comparative educational research: The need for reconceptualisation and fresh insights. Compare, 29(3), 233–248.

Welch, A. (2007). Technocracy, uncertainty, and ethics: Comparative education in an era of postmodernity and globalization. In R. F. Arnove & C. A. Torres (Eds.), Comparative education: The dialectic of the global and the local (3rd ed., pp. 389–403). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Whelan, J. M. (2003). Education and training for effective environmental advocacy. Brisbane: Griffith University.

Yancy, G. (2004). What white looks like: African-American philosophers on the whiteness question. New York: Routledge.

Zimmerer, K. S., & Bassett, T. J. (2003). Political ecology: an integrative approach to geography and environment-development studies. New York: The Guilford Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Misiaszek, G. (2012). Transformative Environmental Education Within Social Justice Models: Lessons from Comparing Adult Ecopedagogy Within North and South America. In: Aspin, D., Chapman, J., Evans, K., Bagnall, R. (eds) Second International Handbook of Lifelong Learning. Springer International Handbooks of Education, vol 26. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2360-3_26

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2360-3_26

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-2359-7

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-2360-3

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)