Abstract

This chapter offers conclusions from the studies included in this text and reiterates ideas for future investigation to further understand how rivalry and group member behavior is influenced by fandom setting. First, the current chapter offers a recap for the studies included in the text. Then, the chapter reiterates how the content in the text could be used by researchers and practitioners attempting to learn more about group behavior. The chapter concludes with ideas for future investigations and avenues that researchers can purpose to further our understanding of individual and group behavior.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The chapters included in the current text investigated how fan setting influenced perceptions and likely behaviors toward rival out-groups. Specifically, Chapter 2 discussed how rivalry perceptions and likely behaviors differed among fans of sport and users of the electronic gaming platforms Xbox and Playstation. Chapter 3 offered a qualitative investigation of comments left in online chatrooms during the 2016 Presidential Debates and the 2016 College Football Season. Next, Chapters 4 and 5 quantitatively investigated how perceptions and likely behaviors differed among fans of sport and Apple/Samsung mobile phones and Star Wars/Star Trek science fiction brands respectively. Chapter 6 then introduced the Group Behavior Composite (GBC) to allow for comparison among nine sport and non-sport settings to determine how group derogation differed among group members. The following sections provide a brief recap of the chapters in this text, along with ways the findings can be used by academics and practitioners, and ideas for future research in the area of group member behavior.

Chapter Recaps

Chapter 2 compared perceptions and likely behaviors toward rival out-groups in sport and among electronic gaming players using the Xbox and Playstation platforms. Sport fans reported significantly higher identification and attitudes toward their favorite sport team than did gamers toward their chosen platform. Additionally, sport fans reported more negative attitudes toward their relevant rival teams, and more negative perceptions toward their rival teams than gamers toward their relevant rival brands. Examining the common in-group (Gaertner et al., 1993), being a fan of both gaming and sport was correlated with more positive views of the relevant gaming rival brand than being a fan of only gaming. No such correlation was present regarding sport fandom (i.e., being a fan of only sport versus both sport and gaming). Finally, comparisons between gamers users revealed that those using the Playstation platform reported more negativity perceptions and likely behaviors toward the Xbox brand than vice versa.

Chapter 3 discussed a qualitative examination of comments left in online chatrooms by sport fans and political supporters. In particular, comments left during the three 2016 Presidential Debates were compared with the comments left surrounding three high-profile college football games. Results found that sport fans tended to show more positivity toward their favorite teams and rival teams than did political commenters. Regarding negativity, sport fans tended to leave more playful jabs at rival teams than did people leaving political comments, however, political commenters left more intense negative comments about their rival groups than did sport fans toward their rival teams.

Chapter 4 compared fans of sport and fans/users of Apple and Samsung mobile phone brands. Comparison showed that fans of sport reported more identification with their favorite team than did mobile phone users. Further, while sport fans reported higher likelihood of supporting a rival sport team in indirect competition than did mobile phone users, they also reported more negative attitudes toward the rival team and likelihood of experiencing greater satisfaction from defeating a rival than in the mobile phone setting. The study also showed that the common in-group influenced some perceptions and likely behaviors toward relevant rival groups among people that were fans of only sport or mobile phone and those that were fans of both sport and mobile phones. Finally, Samsung users reported experiencing greater satisfaction from comparing favorably to Apple than vice versa.

In Chapter 5, we investigated perceptions and likely behaviors toward rival groups among fans of sport and fans of the Star Wars/Star Trek science fiction brands. Following other investigations in the text, sport fans reported greater identification with their favorite brand and more negative perceptions of the rival brand than in the science fiction setting. Again, the common in-group influenced more positive perceptions of the rival science fiction brand (i.e., being a fan of both science fiction and sport), however, being a fan of both sport and science fiction was correlated with more negativity toward the rival team than being a fan of only sport. Finally, fans of the Star Wars brand reported greater identification with their favorite brand and more negativity toward the Star Trek brand than vice versa.

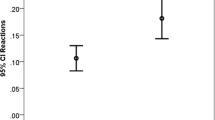

Chapter 6 culminated the investigation portion of the text by comparing group member behavior among nine sport and non-sport settings. Specifically, the three quantitative studies included in the current text were combined with data from investigations about group behavior in sport and Disney Parks (Havard, Wann et al., 2021), comics (Havard, Grieve et al., 2020), politics (Havard, Longo et al., 2021), online electronic gaming (Havard, Fuller et al., 2021), and direct-to-consumer streaming platforms (Havard, Ryan et al., 2021) to provide insight regarding out-group derogation. The chapter introduced the GBC, which combined the four subscales of the Rivalry Perception Scale (RPS, Havard, Gray et al., 2013) and Glory Out of Reflected Failure (GORFing) measure (Havard, 2014; Havard & Hutchinson, 2017)-in order to compare group behavior, along with a hierarchy and spectrum of behavior and out-group derogation. Results indicated that out-group derogation in the online electronic gaming setting was most intense, followed by politics, sport, mobile phones, direct-to-consumer streaming, electronic gaming consoles, Disney Parks, and comics.

Implications and Future Research

As discussed in each investigative chapter throughout the text, the collective findings carry important implications for academics, practitioners, and readers. Specifically, people interested in understanding more about group behavior and out-group derogation can point to the chapters in the text and accompanying comparison investigations for empirical evidence about what setting influence varying amounts of group negativity. For example, researchers and academics can utilize the chapters as an educational text for further insight regarding out-group derogation and group member behavior. Knowing which settings influence more intense out-group derogation also provides researchers with ideas for future investigations that may not be discussed in this text.

For practitioners, it is imperative to understand which fan settings are correlated with more intense out-group derogation and negativity. It is important because practitioners want to engage consumers and brand supporters, something that competition and rivalry can assist with, but they do not want to encourage overly negative, deviant, or violent behavior toward out-groups. Doing so can negatively impact both fans/supporters and brands in a number of ways (Havard, 2020).

Both researchers and practitioners will find importance in the findings regarding the influence of the common in-group (Gaertner et al., 1993) and identify foreclosure (Beaman, 2012). Over the course of the text, and accompanying investigations not included as chapters in the book, being a fan of only one group or both groups of comparison influenced out-group negativity in various ways. For example, being a fan of both brands of comparison was correlated with more positive views of the relevant rival in investigations on Disney Parks (Havard, Wann et al., 2021) and comics (Havard, Grieve et al., 2020). However, being a fan of both sport and a non-sport brand either did not influence significant differences or was correlated with more out-group negativity regarding electronic gaming platforms (Chapter 2) and science fiction (Chapter 5). Using that data, future research should focus on the use of the common fandom settings to examine the extended contact hypothesis, which states that the more interaction someone has with another, the less negativity they may begin to show against the person (Zhou et al., 2018).

A goal of the current text is also to engage readers and encourage continued interest and investigation regarding group member behavior and out-group derogation. As discussed throughout the chapters, more study of group behavior differences is needed to better understand how group relations are impacted by fandom setting. Some ideas for future comparison investigations include religion, alcohol brands, hospitality or travel, and hotel brands. It is a hope that readers of this text will expand this list and add to our understanding of group behavior. Further, as Chapter 6 provided a measure to use when comparing fandom settings, along with a hierarchy and spectrum to add to, future research will continue to enlighten our understanding in the area.

Finally, as Chapter 3 pointed out, qualitative investigation about group behavior is vital to providing more understanding of behavior and out-group derogation. In that vein, qualitative researchers could conduct interviews, focus groups, and document analyses for each study included or discussed in this text, the future suggested investigations mentioned above, and new avenues of group comparison. Engaging in the important work of qualitatively investigating individual stories about how fandom setting impacts group behavior will add to our understanding and lead us in new impactful directions.

This text discussed group behavior and out-group derogation in various sport and non-sport settings. As a society, we continue to strive for better understanding regarding the human condition and group relationships. This is an important task that has the ability to shape the future of our society, hopefully in positive ways. Further, we as a society should always be striving to better understand those similar and different from us, as doing so will also enlighten us on how to treat others, both in-group and out-group members, with respect and compassion. This text provides important findings in this area, along with potential steps to help in the collective pursuit, and if reading this book provides a spark for others to join in this journey, then the author has accomplished his goal.

Thank you for coming on this adventure with me!

Cody T. Havard, Ph.D.

Professor, Kemmons Wilson School

The University of Memphis

References

Beamon, K. (2012). “I’m a baller”: Athletic identity foreclosure among African-American former student-athletes. Journal of African American Studies, 16, 195–208.

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman, B. A., & Rust, M. C. (1993). The common ingroup identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. European Journal of Social Psychology, 4, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.108014792779343000004.

Havard, C. T. (2014). Glory Out of Reflected Failure: The examination of how rivalry affects sport fans. Sport Management Review, 17, 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2013.09.002.

Havard, C. T. (2020). Rivalry in sport: Understanding fan behavior and organizations. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN: eBook – 978-3-030-47455-3, Print – 978-3-030-47454-6.

Havard, C. T., Fuller, R. D., & Padhye, Y. (2021). Let’s settle this on the (online) gridiron: Examining perceptions of rival brands and platforms in gaming and sport. Manuscript under review.

Havard, C. T., Gray, D. P., Gould, J., Sharp, L. A., & Schaffer, J. J. (2013). Development and validation of the Sport Rivalry Fan Perception Scale (SRFPS). Journal of Sport Behavior, 36, 45–65.

Havard, C. T., Grieve, F. G., & Lomenick, M. E. (2020). Marvel, DC, and sport: Investigating rivalry in the sport and comic settings. Social Science Quarterly, 101, 1075–1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12792.

Havard, C. T., & Hutchinson, M. (2017). Investigating rivalry in professional sport. International Journal of Sport Management, 18, 422–440.

Havard C. T., Longo, P., & Theiss-Morse, E. (2021). Investigating perceptions of out-groups in sport and United States politics. Manuscript in Preparation.

Havard, C. T., Ryan, T. D., & Hutchinson, M. (2021). Prime vs. Netflix vs. Investigating fandom and rivalry among direct-to-consumer streaming services. Manuscript under review.

Havard, C. T., Wann, D. L., Grieve, F. G., & Collins, B. (2021, November/December). Happiest place(s) on earth? Investigating the differences (and impact) of fandom and rivalry among fans of sport and Disney’s Theme Parks. Journal of Brand Strategy.

Zhou, S., Page-Gould, E., & Aron, A. (2018). The extended contact hypothesis: A meta-analysis on 20 years of research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(2), 132–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318762647.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Havard, C.T. (2021). Here We Are, There We Go. In: Rivalry and Group Behavior Among Consumers and Brands. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85245-0_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85245-0_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-85244-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-85245-0

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)