Abstract

This chapter explores the role of assessment in improving student success. First, literature regarding assessment characteristics, formative assessment and (peer) feedback, assessment and feedback literacy, the use of technology in assessment, and assessment integrity is discussed. Subsequently, three case studies are presented. The first case study investigates the effect of digital peer feedback on video presentations. Students used the digital platform Pitch2Peer to upload their presentation and provide feedback to at least one peer’s presentation. Results indicate that students’ presentation skills improved after peer feedback, but that this was not always related to received feedback comments. The second case study explores students’ peer feedback beliefs, using the Beliefs about Peer Feedback Questionnaire (BPFQ), and shows that students generally have positive beliefs with regard to peer feedback. The third case study exemplifies a curriculum design focused on assessment, which indicates that deliberate assessment design can have positive effects on student engagement and results. The results from the case studies and the literature emphasise that peer feedback in particular is an important tool in designing assessment and feedback to improve student learning.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Assessment is often used to measure students learning, as evidenced by Popham (2009, p. 5), who definesassessment as ‘a wide variety of evidence-eliciting techniques’. This definition of assessment includes formal exams and tests, as well as more formative ways of gauging whether students have understood a subject, like in-class questioning. The current chapter focuses on how assessment and feedback in higher education can be used to improve students’ learning and success.

The assessment literature often contrasts formativeandsummative assessment. Formative assessment can be labelled assessment for learning, whereas summative assessment is assessment of learning. The main difference between formative and summative assessment lies in their timing and goals. Formative assessment evaluates and monitors students’ learning during the learning process to enhance student learning and improve teachers’ teaching, whereas summative assessment evaluates learning at the end of a course. Formative and summative assessment do not have distinct assessment types; for example, a quiz could be a formative as well as a summative assessment.

The term formative assessment was popularised by Black and Wiliam (1998) and research has indicated thatformative assessment is more beneficial for student learning than summative assessment (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). Formative assessment can inform students which parts of knowledge they already possess and which knowledge they have to develop further. For students to fully develop the missing knowledge, however, it is important that they are also presented with opportunities or indications as to how they can develop the missing knowledge.

This chapter first explores a few facets of assessment that apply to formative as well as summative assessments and subsequently focuses on the design of formative assessment and feedback, followed by a discussion of the use of technology and academic integrity. After an overview of the literature, three case studies that show different assessment and feedback designs, and students’ beliefs about feedback, are discussed.

Assessment in the Curriculum

The way students are assessed is an important part of the curriculum. An assessment can be, for example, a multiple-choice quiz, an exam, a written essay, a presentation or an artefact. There is no clear evidence that some types of assessment lead to more student success than others (Day et al., 2018a). However, Biggs (1996) stressed that assessment should be designed to measure student performance in relation to the learning objectives, a connection he defined as constructive alignment. Sambell and Brown (2020) suggest working together with students to design relevant assessments for authentic assessment. Student involvement in assessment is also apparent in Biggs (1996), who states that the best way to assess higher order learning objectives is to use portfolios where students select their own relevant evidence with regard to learning outcomes. Regardless of the type of assessment, several characteristics of assessment can influence its usefulness for improving studentsuccess.

Assessment Characteristics

Day et al. (2018a) reviewed assessment characteristics and their relation to student grades. They discussed the merits of assessment frequency, mandatory assessments, assessment rewards, feedback and different assessors. The first three are discussed here as assessment characteristics, whereas feedback and assessors get additional attention later in this chapter as individual sections. See Day et al. (2018a) for a full overview of all different characteristics and examples of how these were utilised in different curricula.

Frequent Assessment

In previous research, university teachers and students both lauded the possibility that assessment can help students keep on track with the subject matter taught in the course (Day et al., 2018b). This effect is most prominent when students are frequently assessed throughout a course. In addition to encouraging students to keep up with their coursework, frequent assessment can also be beneficial for cognitive reasons. Dunlosky et al. (2013) describe the benefits of distributed practice, which refers to spreading study work throughout the semester instead of last-minute cramming. According to Dunlosky et al. (2013), distributed practice is one of the two most effective learning strategies, next to practice testing. Since many of students focus their study efforts on assessments (Cohen-Schotanus, 1999), distributed assessments encourage students to distribute their studying as well. Moreover, increasing the number of assessments may lead to increased time on task, which improves learning outcomes (Admiraal et al., 1999). However, frequent assessment can also have negative effects, such as a high assessment workload (Day et al., 2018b). When the workload gets too high this may lead students to prioritise assessments over other coursework or lectures (Harland et al., 2015).

With respect to the frequency of assessments it is important to align the number of assessments to the course goals (compare with constructive alignment; Biggs, 1996). Examples of frequent assessment that have shown positive effects on student grades include weekly quizzes (e.g. Fautch, 2015; Kibble et al., 2011) and a series of writing assignments in a course (e.g. M. Gielen & De Wever, 2015; Mulder et al., 2014). Assessments like classroom discussions or questioning and answering via clickers can be part of every class (e.g. Knight & Wood, 2005).

One way of introducing frequent assessment is by designing programmatic assessment (van der Vleuten et al., 2012). Programmatic assessment is a longitudinal assessment design consisting of several low-stakes assessments that inform learning and can be aggregated to high-stakes pass/fail decisions. Programmatic assessment assumes that a student’s performance on a single assessment is often context dependent and therefore flawed. Van der Vleuten et al. (2012) argue that only an assessment programme designed following the principles of programmatic assessment promotes learning and allows robust decision making on students’performance.

Mandatory Assessment

When assessment is used as an incentive for students to keep up with their study work it may be tempting to make all assessments mandatory. However, Biggs (1996, p. 359) quotes a student teacher who felt that designing a curriculum with ‘numerous rules [..] for [their students] to follow’ where the teacher ‘did all the preparations and planning for them, giving them mountains of homework and short tests to make sure they revise’, actually led to passive and dependent students. In this respect it is very important to keep the course objectives and constructive alignment in mind, where assessment encourages students to engage with the course materials in a meaningful way, for example by eliciting deep learning instead of rote learning.

Results from the literature review show that making assessment activities mandatory does not increase student success significantly (Day et al., 2018a). However, in studies investigating the effects of assessments, mandatory and non-mandatory assessment are usually not compared within a single cohort of a course. Therefore, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions on whether mandatory assessments lead to improved student success.

When assessment is not mandatory some students will usually not complete it, and this self-selection may be detrimental to students’ success. Cano (2011) posits that male students opt-in for assessments less often, which may be problematic, since research at Leiden Law School has shown that male students performed worse than their female peers on courses without mandatory in-course assessment (i.e. assessment during the course period as opposed to at the end of the course; Day et al., 2018c). Since there were no gender differences in courses with in-course assessments, it seemed that making these assessments mandatory helped close the achievement gap between male and femalestudents.

Assessment Rewards

Rewarding students with a percentage of the course grade can be an incentive for them to participate in assessments. Harland et al. (2015) noted that students often prioritise graded work, and even walked out of a non-graded lecture to focus more time on a graded assessment. However, as will be discussed in the following section, rewarding students for assessments may impede their learning. Gibbs and Simpson (2005) found that when students are provided with a grade and feedback at the same time, they often ignore the feedback, a finding that is reiteratedby Winstone and Boud (2020).

Formative Assessment and Feedback

Both summative and formative assessments can be frequent and mandatory, but formative assessment has a different function. As mentioned before, formative assessment is assessment for learning, instead of assessment of learning.

While developing their theory of formative assessment, Black and Wiliam (2009) state that formative assessment consists of five key strategies, which can be found in Table 11.1. These five strategies can subsequently be the reason a teacher employs a specific formative assessment activity, like classroom questioning.

As evidenced by the third strategy formulated by Black and Wiliam (2009), feedback plays an important role in supporting student learning. However, as mentioned before, the combination of feedback and grades may impede the effect of feedback (Winstone & Boud, 2020). Shute (2008) suggests that providing a grade and feedback simultaneously makes students neglect the feedback. Brookhart (2001, p. 164), on the other hand showed that high achieving students are able to use the grades they receive in summative assessments in a formative way by ‘taking stock’ of where their knowledge and skills currently are and how they need to develop these. Taras (2009) has suggested that formative and summative assessment should not be seen as separate assessment functions but as assessment processes, arguing that a single assessment can have summative and formative processes, and that formative and summative assessment cannot exist without each other. Therefore, summative assessment should not be dismissed simply because it may not support learning in the way formative assessment does. Winstone and Boud (2020) formulated several strategies to preserve the function of feedback, conceding that completely disentangling assessment and feedback may not always be possible. These strategies focus, for example, on adaptively releasing grades after students have accessed feedback, or on a conscious curriculum design where students will be able to apply the feedback they received, which corresponds with the aforementioned notion that frequent assessment could be beneficial for learning.

When looking at ways in which assessment can support learning, Gibbs and Simpson (2005) identified ten conditions for this process in higher education (see Table 11.2). Condition 1 reiterates that assessment can help students to spend time on the task, while conditions 2 and 3 invoke constructive alignment (Biggs, 1996). Conditions 4–10 are all related to feedback, which is explored further in the following paragraphs.

Providing students with proper feedback may be one of the most important ways to improve their learning and subsequent success. Black and Wiliam (2009) introduced feedback as one of their key strategies of formative assessment and seven out of ten of Gibbs and Simpsons’ (2005) conditions for assessment that supports learning focus on feedback. Feedback can be defined as the ‘information communicated to the learner that is intended to modify his or her thinking or behaviour for the purpose of improving learning’ (Shute, 2008, p. 154, emphasis added). However, in the last decade, conceptions of feedback as a ‘process whereby learners obtain information about their work […] in order to generate improved work’ (Boud & Molloy, 2013a, p. 6, emphasis added) have become more prevalent (Dawson et al., 2019).

In designing feedback models, Boud and Molloy (2013b) categorise feedback as information within the first model, which they refer to as ‘Feedback Mark 1’. In this model, feedback is teacher centred, and focused on providing students with information they can use to improve themselves. However, Boud and Molloy (2013b) argue that within this model, students are not active participants in their learning, but passive recipients of information. They propose a new model, referred to as the ‘Feedback Mark 2’ model, to more closely fit the feedback as a process definition.

Within the Mark 1 model, where students are passive receivers of information, researchers like Hattie and Timperley (2007) and Shute (2008) have synthesised studies on the content and timing of the provided feedback information. Hattie and Timperley (2007) suggested a model for feedback that consists of answering three questions. They suggest that all students need to know where they are going (course objectives; feed up), how they are doing with regard to the objectives (feedback) and what they should do to reach the objectives (feedforward). These three questions also play a role in Black and Wiliam’s (2009) key strategies for formative assessment. For example, the key strategy ‘clarifying learning intentions and criteria for success’ (p. 8) is clearly related to feed up, whereas ‘providing feedback that moves learners forward’ (p. 8) is feedforward. The feedback model by Hattie and Timperley (2007) also suggests that feedback can be provided at four different levels, that is, the task level, the process level, the self-regulation level, and the self level.

Shute (2008) provided guidelines for formative feedback design based on the literature. Some suggestions are that feedback should be focused on the level of the task instead of that of the learner, including using praise sparingly, because this can focus students’ attention on the self instead of on the task and this may subsequently hinder learning. With regard to the presentation of feedback, Shute (2008) argues that feedback should be clear, but elaborated, and in manageable units. Additionally, she posits that not all students need the same amount and complexity of feedback and that when feedback is too complex it could overwhelm students, making them less likely to learn from the feedback. High achieving students, for example, may only need corrective feedback, whereas low achieving students benefit more from elaborated feedback.

In contrast to the focus on students receiving feedback information in the Feedback Mark 1 model, the Feedback Mark 2 model of active student participation has three main elements (Boud & Molloy, 2013b): the learners, the curriculum and the learning milieu. The first element suggests that learners need to be active participants in their own learning; seeking for feedback to utilise, instead of waiting for a teacher to provide them with information. Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006) proposed seven principles of good feedback on the assumption that all students are able to self-regulate their learning (see Table 11.3).

Nicol (2009) proposed that teachers in higher education should support students in developing their abilities to seek, interpret and utilise feedback and not focus on providing perfect feedback. Yet, recent research by Dawson et al. (2019) reported that students see the content of feedback comments as the most important factor for effective feedback, although the quality of the content that was cited by students most often was its usability.

The second element of the Feedback Mark 2 model of active student participation focuses on thecurriculum, where feedback should be a central means of engaging students (Boud & Molloy, 2013b). Boud and Molloy propose eight features of the curriculum that are necessary to facilitate active participation of students in the feedback process, which can be found in Table 11.4.

The final element of Mark 2 is the learning milieu, or the translation of the designed curriculum to everyday learning. According to Boud and Molloy (2013b, p. 708), ‘feedback Mark 2 is dependent on a learning environment that fosters continual improvement and creates opportunities for knowledge seeking and application by students.’ In this milieu, there should be extensive opportunities for all forms of dialogue, and learners should trust that the teacher and their peers provide relevant and qualitative comments, since students will be apprehensive to act on the basis of irrelevantcomments.

Peer and Self-Assessment

Teachers are usually the assessor of student learning, but students can also assess each other or themselves. Black and Wiliam (2009) indicated the importance of peer and self-assessment, by relating their final two key strategies to activating students as educational resource for each other (peer assessment) and owners of their own learning (self-assessment). Peer and self-assessment also fit within curriculum features proposed by Boud and Molloy (2013b), where ‘calibration mechanisms’ (p. 707) include having students judge their own work (self-assessment) and ‘learner as seeker and provider’ (p. 707) suggests that students should practice giving as well as receiving feedback (peer assessment).

Peer assessment andpeer feedback are often used interchangeably; however, peer assessment does not always include the opportunity for students to provide feedback to each other. For example, peers scoring each other’s work would be regarded as peer assessment, but including comments for improvement ispeer feedback. Peer feedback may be especially helpful because students often have a similar level of understanding, meaning they provide feedback at the level it is needed, in accordance with Shute’s (2008) suggestion that feedback should be provided on the learner’s level. According to Topping (1998), peer feedback could be beneficial because a more competent peer suggests points of improvement, or because the feedback provider has different opinions.

Several researchers have studied the merits of peer assessment compared to teacher assessment. H. Li et al. (2020) found that students who participate in peer assessment, whether this was grades only, grades and comments, or comments only, show greater improvement than students who participate in teacher assessment only, or in no assessment at all. However, Snowball and Mostert (2013) found that students are often mild graders to their peers.

When looking specifically atpeer feedback, Patri (2002) found that students can provide feedback on a similar level as teachers, if they are provided with clear feedback criteria. Research into students’ acceptance ofpeer feedback has shown contrasting results. Welsh (2012), for example, found that students are willing to acceptpeer feedback and value it as much as teacher feedback. In contrast, McConlogue (2015) suggests that not all students will fully engage withpeer feedback because, for example, some peers do not put a lot of effort into their feedback, or because students do not trust the quality of their peers as feedback providers. Admiraal (2014) also found that students prefer teacher feedback. Some of students’ scepticism towardspeer feedback could be overcome by engaging students in extensivepeer feedback training (Huisman et al., 2020), or by providing students with opportunities to strengthen trust in their peers (Boud & Molloy, 2013b).

Several authors have argued that the process of providingpeer feedback could be more beneficial for students than the process of receiving feedback. Lundstrom and Baker (2009), for example, found that feedback providers showed greater improvement than feedback receivers. Topping (1998) argues that providing peer feedback makes students spend additional time on the task and helps them reflect on the assessment criteria, which they subsequently can apply to their own work. Boud and Molloy (2013b) note that students being providers of feedback, and not just receivers, is an important feature of good curriculum design for Feedback Mark 2.

Van Zundert et al. (2010) suggest that for students to be able to provide high qualitypeer feedback, they should get peer feedback training. Peer feedback training can also improve students’ attitudes towardspeer feedback, which in turn may influence their behaviour during thepeer feedback process (Huisman et al., 2020).

Topping (1998) synthesised a typology ofpeer feedback, consisting of 17 variables that can vary in a peer feedback assignment, which was extended to 20 variables by S. Gielen et al. in 2011. Van den Berg et al. (2006a) studied the outcomes of varying several of these variables and found that having sufficient time between peer and final teacher assessment, providing reciprocalpeer feedback, and feedback groups of three to four students were most beneficial for effectivepeer feedback. Results indicated that students revising their assignments based on receivedpeer feedback did not get higher grades than students who did not receivepeer feedback in this study. However, students did show significant improvement from draft to final version (van den Berg et al., 2006a).

In addition to peer assessment, students can also assess themselves, often using rubrics or lists of assessment criteria. Self-assessment may be beneficial for similar reasons as providing peer assessment, like reflecting on assessment criteria and increased time on task. Boud and Molloy (2013b) also noted the importance of providing students with the opportunity to check their work before it is graded. However, research has indicated that there are often discrepancies between outcomes of teacher and self-assessment. Some examples of these are that more advanced students are more accurate raters than their less advanced peers (Falchikov & Boud, 1989), and that high achieving students underrate theirperformance, whereas low achieving students overrate themselves (De Grez et al., 2012; Topping, 1998). Furthermore, Torres-Guijarro and Bengoechea (2017) found that female engineering students often underratethemselves.

Assessment Literacy and Feedback Literacy

Students also have an important part in achieving student success through assessment. In order to be effective, students need to be active participants in the feedback process (Boud & Molloy, 2013b) and engage with the assessment and its feedback in a meaningful way (compare conditions 9 and 10 by Gibbs & Simpson, 2005). To be able to truly benefit from assessment, students should be assessment and feedback literate.

Assessment literacy is defined by Smith et al. (2013, p. 46) as ‘students’ understanding of the rules surrounding assessment in their course context, their use of assessment tasks to monitor or further their learning, and their ability to work with the guidelines on standards in their context to produce work of a predictable standard’. It is important for students to develop assessment literacy because students who show assessment literacy are able to judge and monitor their performance and are able to take responsibility for their own learning. In addition to students’ assessment literacy, Popham (2009) also focuses on the importance of assessment literacy for (school) teachers, stating that teachers who are assessment literate make better decisions relating to assessment. However, a full discussion of assessment and feedback literacy for teachers is beyond the scope of this chapter.

In addition to the concept of assessment literacy, Carless and Boud (2018, p. 1316) define feedback literacy as ‘the understandings, capacities and dispositions needed to make sense of information and use it to enhance work or learning strategies’, which is an extension of Sutton’s (2012) concept of feedback literacy. Carless and Boud (2018) propose a framework for feedback literacy that consists of four features. First, students should appreciate the feedback process by seeing the value of feedback and their active role in the process. Students should not rely on the teacher to reveal the correct answers, a process that Carless and Boud (2018, p. 1317) refer to as ‘feedback as telling’. Second, students should be able to make judgements about the quality of their work, or the work of their peers. Third, students should manage their emotions and attitudes surrounding feedback, since they often feel defensive in response to feedback, especially when it is critical. The fourth and final aspect of the framework is taking action, which follows after students engage with the first three processes. Again, Gibbs and Simpson (2005) already argued that assessment only supports learning when students act upon feedback. Molloy et al. (2020) applied the four key features of the conceptual feedback literacy model proposed by Carless and Boud (2018) to empirical student data, to further explore the concept of feedback literacy and to get a student perspective on feedback literacy. Their results indicate that students incorporate the features proposed by Carless and Boud (2018) into their feedback practice. Since learners’ perspectives on feedback are very important if they need to be an active participant in the feedback process, Molloy et al. (2020) developed a learner- centred framework consisting of seven groups of feedback literacy behaviours. These groups are, ‘commits to feedback as improvement’, ‘appreciates feedback as an active process’, ‘elicits information to improve learning’, ‘processes feedback information’, ‘acknowledges and works with emotions’, ‘acknowledges feedback as a reciprocal process’ and ‘enacts outcomes of processing of feedback information’ (Molloy et al., 2020, p. 529). The expanded view on student feedback literacy following from these results can be used in designing learning environments that foster feedback literacy.

Improving Assessment and Feedback Literacy

Since assessment and feedback literacy are prerequisites for a successful assessment and feedback practice, teachers should try to improve both types of literacy from the start of students’first year. In the same way that assessment and feedback are closely related, assessment and feedback literacy are strengthened using similar methods, where developing students’ skills in judgement seems to be the most important.

Smith et al. (2013) studied the effects of a 45-minute assessment literacy intervention where students graded two exemplar assignments, decided which was the better assignment, and compared their judgements to the assessment rubric. After this intervention, students’ assessment literacy (understanding and judgement) and use of assessment for learning increased. Subsequently Smith et al. (2013) found that the increase in ability to judge the value of their own (or others’) work was related to increased learning outcomes.

In a similar vein, Carless and Boud (2018) suggest that the best way to improve feedback literacy is by having students analyse exemplars and by providing and receiving peer feedback. When students analyse exemplar assessments, they are familiarised with teachers’ expectations with regard to assessment quality. Furthermore, seeing high quality work and comparing the quality of different exemplar assignments helps students develop their skills in academic judging. Providing as well as receiving peer feedback can help to develop feedback literacy by putting the responsibility for feedback in students’ hands, and again by developing their academic judgement. Malecka et al. (2020) formulated four principles for incorporating feedback literacy in thecurriculum: ‘feedback is consciously designed’, and not a last-minute decision in course development; ‘students get ample opportunity to practice eliciting, processing and applying feedback’; ‘feedback literacy is incorporated in a cumulative and progressive fashion’, resulting in further development of assessment literacy over the course of students’ educational career; and ‘feedback is traceable’, which makes it easier for teachers to build on previous feedback, or see how students have processed the feedback. Malecka et al. (2020) provide examples of practices for the development of feedback literacy, like the use of e-portfolios which can enable students to ‘revisit feedback, set their own developmental goals and document progress’ (p. 11).

Carless and Boud (2018) suggest that feedback literacy can only develop when teachers design their curriculum for active studentparticipation, because students need to actively work on improving their feedback literacy (compare the importance of curriculum and milieu in Boud & Molloy, 2013b). Furthermore, teachers should explain the importance of the learning activities related to the development of feedback literacy and discuss any discrepancies between teacher and student views about feedback. Teachers could also explain to students how academics are exposed to peer feedback and model theirresponses.

Technology

Assessment and feedback can be enhanced by technology. Using technology like online platforms for feedback and assessment increases the possibility for asynchronous feedback providing, which makes them especially suited for use in online and distance learning where students may not be available at the same time as their peers. Brown and Sambell (2020) explored alternatives for face-to-face assessment in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and suggest several technological options, like online peer assessment or having students prepare a podcast instead of a presentation. Their further work on how assessment should be designed post-pandemic (Sambell & Brown, 2020) also heavily incorporates technological measures.

However, before the pandemic, technology was already playing an important role in assessment. Over half of the studies discussed in the review by Day et al. (2018a) used computers or an online environment for assessment. One example of such a study is the one by Nicol (2009) where students’ learning was improved by giving them ample assessment opportunities through an online environment, and where teachers could monitor students’ learning through the platform, to adapt their teaching where necessary.

Shute (2008) suggests that feedback which is provided on paper or online is attended to more than oral feedback and H. Li et al. (2020) found that computer-mediated peer feedback provided increased learning gains when compared to pen-and-paper-based peer feedback. In recent research, peer feedback is often provided through digital platforms like Turnitin (e.g. Huisman et al., 2017; Huisman et al., 2018; Nicol et al., 2014). Carless and Boud (2018) praised the speed of delivery and portability of digital peer feedback.

Digital feedback platforms have several characteristics that can aid the feedback process. These platforms (e.g. TurnitinorPitch2Peer) can often automatically match peers into feedback couples. Furthermore, online peer feedback can easily remain anonymous, which may increase the effect of peer feedback (L. Li, 2017).

Van der Pol, Admiraal and Simons (2006) found that annotating online discussion to specific text elements led to improved outcomes compared to standard discussions. This annotating of comments and feedback to specific information is also facilitated by digital peer feedback platforms, especially when feedback is provided on videos or other non-writtenassignments.

Academic Integrity

When discussing assessment, it is important to focus on facets of academic integrity and cheating as well. Research shows a wide variety in the prevalence of cheatingbehaviours by students. Dawson (2021) cites studies with prevalences ranging from 1% to 20% and Australia’s Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA, 2017) cites up to 72%, dependent on the definition of cheating. The focus on cheating and academic integrity is especially important in the current context, where assessments are technology-moderated more often, and students are being assessed remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ryan et al. (2020), for example, discovered that academic integrity guidelines are often focused on plagiarism and collusion, but not on cheating during (remote) exams. Subsequently, students’ ideas about academic integrity did not transfer to the new context of remote examination.

Dawson (2021), in his latest book, has focused on how students use technology to cheat, so-callede-cheating. Dawson argues that technology has introduced new ways of cheating, like paraphrasing tools or having a third party log in to an online examination, but it has also further facilitated contract cheating (e.g. hiring someone to write an essay), due to the use of online platforms to connect cheaters and writers or the added anonymity by encryption on the internet.

An important way to prevent cheating may lie in assessment design. The UK’s Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA, 2017) suggests, for example, to use multiple different assessment methods, or to introduce authentic assessments. Authentic assessments ‘better reflect the complex challenges [students] will face in the real world’ (Ellis et al., 2020, p. 455) and thus serve an important pedagogical function. According to Ellis et al. (2020) researchers assume that authentic assessment makes contract cheating less likely, more difficult, or easier to detect. Sambell and Brown (2020) state that the authenticity of an assessment not only relates to employability and the development of professional skills, but they explicitly include academic integrity in their definition of authentic assessment. Furthermore, their suggestion to involve students in the design of meaningful and authentic assessments may also work as a deterrent for cheating. However, Ellis et al. (2020) found that students still engaged in contract cheating when authentic assessments were used.

In addition to assessment design, TEQSA (2017) proposed 21 good practices to promote, address breaches of, and mitigate risks to, academic integrity. Additionally, the QAA (2020) has published a guidance on assessment integrity during digital education, which also includes best practices, and reflective questions educators can ask themselves when moving their assessmentonline.

Cases

This section describes three cases related to feedback and assessment. Cases one and three are examples of how assessment can be used to improve student learning and student success, whereas case two focuses on the student experience of peer feedback. The first case focuses on the use of peer feedback, since both assessment literacy and feedback literacy can be improved by having students look at exemplar assessments to develop their capabilities of judging the quality of work. The second case investigates students’ beliefs with regard to peer feedback. The third case focuses on how assessment can be part of a curricular redesign.

Case 1: Peer Feedback on Draft Presentations

At Leiden University the use of peer feedback on writing assignments has been studied in several educational programmes, like the bachelor programmes Biopharmaceutical Sciences or Child and Education studies (Huisman et al., 2017; Huisman, et al., 2018). Topping (1998) described that the majority of peer feedback research has focused on writing assignments, but that peer feedback is also suitable for other types of assessment, such as assignments for assessing presentations or professional skills. We have previously studied the use of peer feedback in presentation assignments (Day et al., 2021) and will discuss this further in the following section.

In the design of the peer feedback assignment, Black and Wiliam’s (2009) key strategies 1 (criteria for success) and 4 (peers as instructional resource) were utilised. Furthermore, several of the conditions for learning from assessment as addressed by Gibbs and Simpson (2005), like providing feedback when students can still process it, and curriculum features proposed by Boud and Molloy (2013b), like nested tasks to allow for feedforward, were incorporated as well.

Methods

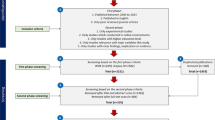

This case focuses on a Chemistry course part of the bachelor degree Liberal Arts and Sciences at Leiden University College (an international honours college) and an Academic Skills and Workplace Orientation course part of the bachelor Child and Education Studies at the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences.

Six students were enrolled in the Chemistry course, an eight-week course consisting of 14 biweekly lectures, graded homework assignments, an essay and presentation, and a final exam. For the presentation students were required to upload a draft and provide peer feedback to two of their fellow students.

Students were required to give a 5–10 minute presentation about a subtopic of chemistry of their personal interest. The researcher came to a class meeting to introduce Pitch2Peer, the digital platform where students needed to upload their draft presentation videos, and the rubric they would use for providing feedback. Since students already had experience with presenting and providing peer feedback through other courses in their program, the instruction given in the introductory meeting did not include strategies for peer assessment.

Fifty-six students (about 60% of those enrolled) in the Child and Education Studies course participated in the study. This year-long course focused on skill development and exploration of the work field of child and education studies and consisted of five work group meetings and several colloquia. All students were required to give a 7–8 minute presentation about the different Child and Education Studies Masters’ programmes as offered by Leiden University. In this presentation students focused on the courses in the programme, entrance requirements, and career opportunities. Students usually presented in duos, but depending on the size of their specific work group, presenters could also be solo or in a trio. In preparation for the presentation, the researcher gave a lecture on presentation and feedback skills, and introduced the Pitch2Peer platform.

In both courses, the presentation rubric focused on four general categories: content, manner of speaking, presence, and use of audio-visual equipment. The latter three categories have the same subcategories in both courses, but for the Child and Education Studies course, two subcategories of the content category were replaced with one subcategory focusing on whether students met all required components of the presentation. The full rubric including all subcategories for each main category can be found in Table 11.5.

The timelines for the two courses were slightly different. In the Chemistry course students needed to upload their presentation into Pitch2Peer, a digital peer feedback environment, one week before their final class presentation. Peers had three days to rate two presentations on a scale of one to five for each category of the presentation rubric, annotate any specific comments they had to specific moments in the video, and write a general feedback comment where they could further expand on the reasoning for their rating. Students could subsequently use the feedback to improve their final presentation. Final presentations were held in class and videotaped by the researcher. Grades for the presentation were awarded by the teacher, without input from the researcher, but were not used in this study. In the Child and Education studies course, students submitted their trial presentations two weeks before the final class presentation, and peers had a full week to provide peer feedback. Just like the chemistry students, they were required to rate the presentation, annotate a specific moment, and write a general comment. Each presenting duo provided feedback to one presentation. Presentations were mandatory but not graded.

To prepare for analysis the researcher rated the draft and final presentation videos using the presentation rubric, and subsequently the scores on the draft and final presentations were compared to investigate whether students’ presentation skills improved from the draft to the final presentation. Furthermore, received feedback comments were coded using a matrix of feedback functions and aspects used in previous research (e.g. van den Berg et al., 2006b; Huisman et al., 2017, 2018). Feedback functions are analysis, evaluation, revisions and elaborations on the latter two, and feedback aspects are the four main rubric categories: content, manner of speaking, presence and audio-visual equipment.

Results

Students in both programmes received between 5 and 64 feedback comments. Generally, students mainly provided comments coded as evaluation, giving explicit and implicit quality statements, and less than 30% of feedback was focused on suggested revisions.

Chemistry Students

Comparing students’ mean scores across all 23 rubric subcategories for the draft and final presentation using a paired samples t-test indicates that students’ presentation skills improved, t(5) = −4.33, p = 0.008. On the draft presentation, students’ mean score was 3.04 out of 5, which improved to 4.00 on the final presentation.

One student did not provide peer feedback, resulting in two students having only one peer feedback provider, whereas all other students had two feedback providers. Investigating how received feedback comments were related to improvement in the presentation revealed a negative connection, r = −0.82, p = 0.047. This negative connection can be explained by the fact that the two students who only had one feedback provider showed the greatest improvement. These students both performed worse than the others on the draft presentation and therefore had the most room for improvement.

Child and Education Studies Students

A comparison of the mean scores for the draft and final presentation paints a similar picture as for the chemistry students, t(49) = −7.50, p < 0.001, although the child and education studies show a smaller increase in score from draft to final presentation, going from 3.73 out of 5 to 4.12. The majority of students (62.5%) received feedback from a single peer, whereas 37.5% of students had two peer feedback providers. Analysis of the relation between received feedback and improvement between the draft and final presentation showed no correlation, r = −0.076, p = 0.622.

Case 2: Students’ Beliefs About Peer Feedback

Some of the literature discussed in this chapter indicates that peer feedback can be beneficial for student learning, but that students may be not as receptive to peer feedback as to teacher feedback (Admiraal, 2014; McConlogue, 2015). Huisman et al. (2020) hypothesised that students’ beliefs about peer feedback can influence their subsequent feedback behaviours, and they developed theBeliefs about Peer Feedback Questionnaire (BPFQ) to measure these beliefs. The BPFQ consists of eleven questions divided in four scales. The first scale is the valuation of peer feedback as an instructional method (VIM) and has four questions, the second scale has three questions focusing on the valuation of peer feedback as an important skill (VPS), the third and fourth scale focus on confidence in the quality of received peer feedback (CR) and confidence in own peer feedback quality (CO), with two questions in each scale. All questions are answered on a five-point Likert scale.

Methods

The current case showcases the peer feedback beliefs of students in the master Child and Education Studies: Learning Problems and Impairments (N = 10) and students in the second year of the Cultural Anthropology bachelor programme (N = 21). All students participated in a peer feedback assignment focusing on a video (a knowledge clip for Child and Education Studies, a presentation for Anthropology). After they received peer feedback, they answered a prototype of theBPFQ. Due to a misprint in the questionnaire, Anthropology students only had one question in the CR scale.

Results

For an overview of all results see Table 11.6. Results indicate that students in both programmes in general have positive beliefs with regard to peer feedback, with the students in the Bachelor of Anthropology being more positive than the students in the Master Child and Education studies. This difference is significant for the scales VIM, t(10.76) = −3.17, p = 0.009, and CR, t(12.57) = −2.95, p = 0.012. According to Huisman et al. (2020) the VIM and CR scales may be conceptually related, which can explain the fact that Master Child and Education studies students score significantly lower on both scales. However, these students still display generally positive beliefs, indicated by their scores of higher than three out of five on all fourscales.

Case 3: Assessment in the First-Year Curriculum of an Undergraduate Law School

The undergraduate law program at Leiden law school enrols about a thousand first-year students each year. The majority of these students major in law, but about 10% major in criminology. In the first year there is substantial overlap in the course load of the two majors. In an attempt to increase the percentage of students who graduate from the three-year program in a maximum of four years, the educational leadership of the law school initiated curricular reform. Previous research (e.g. Boud & Molloy, 2013b; Malecka et al., 2020) stated the importance of deliberate curriculum design for assessment and feedback. Starting in the 2013–2014 academic year, a revised curriculum with added focus on in-course assessment was introduced for all new first-year undergraduate law and criminology students. On top of the addition of in-course assessments, this curricular reform also included added contact hours in the form of tutorial meetings. Furthermore, a course that was regarded as being tough was moved to the start of the curriculum, to function as an early sorting mechanism. With regard to assessment, full semester courses had to have a mandatory partial exam. Half-semester courses could choose to include additional assessments in their course and teachers were free to design their own assessments.

About half of the courses in the curriculum had in-course assessments. For several of the criminology courses the use of in-course assessment was more common and already standard practice, but for the law program the assessment was usually new. Teachers often opted for assessments that would keep students on track with their study work (compare conditions 1 & 2; Gibbs & Simpson, 2005), and that could be used to measure course goals that are not easily assessed with a multiple choice final exam (compare constructive alignment; Biggs, 1996). These assessments often took the shape of mandatory preparation assignments for the weekly tutorial meetings, where students would then receive correct answers and general feedback. See Day et al. (2018b) for a full overview of all different types of assessment that were employed in the law program.

Results

As part of the Day et al. (2018b) study, teachers were asked if the new assessment system improved students’ results. The majority of teachers mentioned feeling that students were better prepared and more engaged in class. Furthermore, some courses had improved passing percentages, but teachers were hesitant to connect these to the introduction of assessment, because of the other facets of the curricular change. This also made cohort comparisons impossible, but when first-year students’ outcomes in courses with and without in-course assessment were compared in the 2014–2015 academic year, results indicated that students were not performing better in courses that used in-course assessment than in courses that only had a final assessment, t(88) = −0.71, p = 0.48. The difference in performance on courses with and without in-course assessment and the possible role of assessment type and student characteristics in this difference is furtherexplored in Day et al. (2018c).

Conclusion

This chapter has discussed how assessment and feedback can be utilised to improve student success. Several characteristics of assessment can make it a potent driver of student learning. Assessing students frequently, for example, encourages them to spend more time studying, and provides students with the opportunity to utilise feedback (Boud & Molloy, 2013b). Furthermore, assessment can promote learning throughformative assessment, which is designed with the explicit goal of supporting learning, and the use of feedback.

Several authors (i.e. Black & Wiliam, 2009; Gibbs & Simpson, 2005) have discussed properties of assessment that improve student learning, where the focus is on making assessment criteria explicit, eliciting time-on-task and providing feedback. With regard to feedback Hattie and Timperley (2007) stress the importance of feedforward, or telling students what they need to do to reach the course criteria, and Boud and Molloy (2013b) focus on the role of the student as an active seeker of feedback.

An important example of using assessment to improve student success is having students provide peer feedback, as discussed in the first case. Another benefit of peer feedback assessments is that the process of looking at each other’s presentations and applying the scoring rubric to the work of their peers helps improve students’ assessment and feedback literacies (Smith et al., 2013; Carless & Boud, 2018).

Providing peer feedback is beneficial because the peer feedback provider reflects on the assessment criteria, and receiving good peer feedback, or maybe good ‘peer feedforward’ is beneficial because it can help students see where they need to go in order to improve their work. For successful peer feedback it is important that students receive peer feedback training (van Zundert et al., 2010). Additionally, the process of providing peer feedback may develop students’ feedback literacy (Carless & Boud, 2018), and when peer feedback training consists of having students judge exemplar assignments the process can also boost assessment literacy (Smith et al., 2013).

The cases show examples of assessment and feedbackin higher education. Case 3 provides insight in how assessment should be an integral part of curricular design, which corresponds with the concept of constructive alignment (Biggs, 1996). The first and second case are more specifically focused on students’ use of, and beliefs about, peer feedback.

The results of the first case should be interpreted cautiously, because of the small sample size in the Chemistry course. Yet, this case shows the potential for using a peer feedback assignment for improving studentperformance. In the data from Child and Education Studies students discussed in case 1, no connection between received feedback comments and improvement was found. These results warrant further investigation of the relation between peer feedback and students’ improvement on presentation skills. Results from the second case show that students have generally positive beliefs with regard to peer feedback, which corresponds with the results of Huisman et al. (2020).

To conclude, assessment and feedback are highly intertwined, and can both be potent drivers of student learning and student success if they are employed thoughtfully.

References

Admiraal, W. F. (2014). Meaningful learning from practice: Web-based video in professional preparation programmes in university. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 23, 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2013.813403

Admiraal, W., Wubbels, T., & Pilot, A. (1999). College teaching in legal education: Teaching method, students’ time-on-task, and achievement. Research in Higher Education, 40(6), 687–704. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018712914619

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability (formerly: Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education), 21(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5.

Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2013a). What is the problem with feedback? In D. Boud & E. Molloy (Eds.), Feedback in higher and professional education: Understanding it and doing it well (pp. 1–10). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203074336

Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2013b). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: The challenge of design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 698–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2012.691462

Brookhart, S. M. (2001). Successful students’ formative and summative uses of assessment information. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 8(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940123775

Brown, S., & Sambell, K. (2020, March 13). Contingency-planning: Exploring rapid alternatives to face-to-face assessment. Retrieved from https://sally-brown.net/kay-sambell-and-sally-brown-covid-19-assessment-collection/

Cano, M. D. (2011). Students’ involvement in continuous assessment methodologies: A case study for a distributed information systems course. IEEE Transactions on Education, 54(3), 442–451. https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2010.2073708

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Cohen-Schotanus, J. (1999). Student assessment and examination rules. Medical Teacher, 21(3), 318–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421599979626

Dawson, P. (2021). Defending assessment security in a digital world: Preventing e-cheating and supporting academic integrity in higher education. Routledge.

Dawson, P., Henderson, M., Mahoney, P., Phillips, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2019). What makes for effective feedback: Staff and student perspectives. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877

Day, I.N.Z., Saab, N, & Admiraal, W.F., (2021). Online peer feedback on video presentations: Type of feedback and improvement of presentation skills. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1904826.

Day, I. N. Z., van Blankenstein, F. M., Westenberg, M., & Admiraal, W. F. (2018a). A review of the characteristics of intermediate assessment and their relationship with student grades. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(6), 908–929. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1417974

Day, I. N. Z., van Blankenstein, F. M., Westenberg, P. M., & Admiraal, W. F. (2018b). Teacher and student perceptions of intermediate assessment in higher education. Educational Studies, 44(4), 449–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2017.1382324

Day, I. N. Z., van Blankenstein, F. M., Westenberg, P. M., & Admiraal, W. F. (2018c). Explaining individual student success using continuous assessment types and student characteristics. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(5), 937–951. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1466868

De Grez, L., Valcke, M., & Roozen, I. (2012). How effective are self- and peer assessment of oral presentation skills compared with teachers’ assessments? Active Learning in Higher Education, 13(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787412441284

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Ellis, C., van Haeringen, K., Harper, R., Bretag, T., Zucker, I., McBride, S., Rozenberg, P., Newton, P., & Saddiqui, S. (2020). Does authentic assessment assure academic integrity? Evidence from contract cheating data. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(3), 454–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1680956

Falchikov, N., & Boud, D. (1989). Student self-assessment in higher education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 59(4), 395–430. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543059004395

Fautch, J. M. (2015). The flipped classroom for teaching organic chemistry in small classes: Is it effective? Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 16(1), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4rp00230j

Gibbs, G., & Simpson, C. (2005). Conditions under which assessment supports students’ learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1(1), 3–31. Retrieved from http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/3609

Gielen, M., & De Wever, B. (2015). Structuring the peer assessment process: A multilevel approach for the impact on product improvement and peer feedback quality. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 31(5), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12096

Gielen, S., Dochy, F., & Onghena, P. (2011). An inventory of peer assessment diversity. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(2), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903221444

Harland, T., McLean, A., Wass, R., Miller, E., & Sim, K. N. (2015). An assessment arms race and its fallout: High-stakes grading and the case for slow scholarship. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(4), 528–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.931927

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Huisman, B., Saab, N., van Driel, J., & van den Broek, P. (2017). Peer feedback on college students’ writing: Exploring the relation between students’ ability match, feedback quality and essay performance. Higher Education and Development, 36, 1433–1447. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1325854

Huisman, B., Saab, N., van Driel, J., & van den Broek, P. (2018). Peer feedback on academic writing: Undergraduate students’ peer feedback role, peer feedback perceptions and essay performance. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43, 955–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1424318

Huisman, B., Saab, N., Van Driel, J., & Van Den Broek, P. (2020). A questionnaire to assess students’ beliefs about peer-feedback. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 57, 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2019.1630294

Kibble, J. D., Johnson, T. R., Khalil, M. K., Nelson, L. D., Riggs, G. H., Borrero, J. L., & Payer, A. F. (2011). Insights gained from the analysis of performance and participation in online formative assessment. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 23(2), 125–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2011.561687

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254

Knight, J. K., & Wood, W. B. (2005). Teaching more by lecturing less. Cell Biology Education, 4(4), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1187/05-06-0082

Li, H., Xiong, Y., Hunter, C. V., Guo, X., & Tywoniw, R. (2020). Does peer assessment promote student learning? A meta-analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1620679

Li, L. (2017). The role of anonymity in peer assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(4), 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1174766

Lundstrom, K., & Baker, W. (2009). To give is better than to receive: The benefits of peer review to the reviewer’s own writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18, 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2008.06.002

Malecka, B., Boud, D., & Carless, D. (2020). Eliciting, processing and enacting feedback: Mechanisms for embedding student feedback literacy within the curriculum. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1754784.

McConlogue, T. (2015). Making judgements: Investigating the process of composing and receiving peer feedback. Studies in Higher Education, 40(9), 1495–1506. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.868878

Molloy, E., Boud, D., & Henderson, M. (2020). Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(4), 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955

Mulder, R., Baik, C., Naylor, R., & Pearce, J. (2014). How does student peer review influence perceptions, engagement and academic outcomes? A case study. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(6), 657–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.860421

Nicol, D. (2009). Assessment for learner self-regulation: Enhancing achievement in the first year using learning technologies. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(3), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930802255139

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

Nicol, D., Thomson, A., & Breslin, C. (2014). Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: A peer review perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(1), 102–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.795518

Patri, M. (2002). The influence of peer feedback on self- and peer-assessment of oral skills. Language Testing, 19, 109–131. https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532202lt224oa

Popham, W. J. (2009). Assessment literacy for teachers: Faddish or fundamental? Theory Into Practice, 48(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802577536

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. (2017). Contracting to cheat in higher education: How to address contract cheating, the use of third-party services and essay mills. Retrieved from https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/quality-code/contracting-to-cheat-in-higher-education.pdf

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. (2020). Assessing with integrity in digital delivery. Retrieved from https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/guidance/assessing-with-integrity-in-digital-delivery.pdf

Ryan, A., Hokin, K., Judd, T., & Elliott, S. (2020). Supporting student academic integrity in remote examination settings. Medical Education, 54, 1075–1076. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14319

Sambell, K., & Brown, S. (2020, June 1). The changing landscape of assessment: Some possible replacements for unseen time-constrained face-to-face invigilated exams [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://sally-brown.net/kay-sambell-and-sally-brown-covid-19-assessment-collection/

Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 153–189. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654307313795

Smith, C. D., Worsfold, K., Davies, L., Fisher, R., & McPhail, R. (2013). Assessment literacy and student learning: The case for explicitly developing students ‘assessment literacy’. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(1), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.598636

Snowball, J. D., & Mostert, M. (2013). Dancing with the devil: Formative peer assessment and academic performance. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(4), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.705262

Sutton, P. (2012). Conceptualizing feedback literacy: Knowing, being and acting. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 49, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.647781

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. (2017). Good practice note: Addressing contract cheating to safeguard academic integrity. Retrieved from https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/default/files/good-practice-note-addressing-contract-cheating.pdf?v=1507082628

Taras, M. (2009). Summative assessment: The missing link for formative assessment. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 33(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770802638671

Topping, K. (1998). Peer assessment between students in colleges and universities. Review of Educational Research, 68(3), 249–276. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543068003249

Torres-Guijarro, S., & Bengoechea, M. (2017). Gender differential in self-assessment: A fact neglected in higher education peer and self-assessment techniques. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(5), 1072–1084. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1264372

van den Berg, I., Admiraal, W., & Pilot, A. (2006a). Design principles and outcomes of peer assessment in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 31(3), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600680836

van den Berg, I., Admiraal, W., & Pilot, A. (2006b). Peer assessment in university teaching: Evaluating seven course designs. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930500262346

van der Pol, J., Admiraal, W., & Simons, P. R. J. (2006). The affordance of anchored discussion for the collaborative processing of academic texts. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 1(3), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-006-9657-6

van der Vleuten, C. P. M., Schuwirth, L. W. T., Driessen, E. W., Dijkstra, J., Tigelaar, D., Baartman, L. K. J., & van Tartwijk, J. (2012). A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Medical Teacher, 34(3), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2012.652239

van Zundert, M., Sluijsmans, D., & van Merriënboer, J. (2010). Effective peer assessment processes: Research findings and future directions. Learning and Instruction, 20(4), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.004

Winstone, N. E., & Boud, D. (2020). The need to disentangle assessment and feedback in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687.

Welsh, M. (2012). Student perceptions of using the PebblePad e-portfolio system to support self- and peer-based formative assessment. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 21(1), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2012.659884

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Day, I.N.Z., Admiraal, W., Saab, N. (2021). Designing Assessment and Feedback to Improve Student Learning and Student Success. In: Shah, M., Kift, S., Thomas, L. (eds) Student Retention and Success in Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80045-1_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80045-1_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-80044-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-80045-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)