Abstract

This introductory chapter presents a focused survey of the literature on the interaction between depression and personality, which represents one of the approaches to the issue of complex depression, which is treated from different perspectives throughout this book. Patients who, in addition to a depression, present with personality dysfunction are more than twice as likely to be nonresponders to treatment compared to patients with common, stand-alone depression. Furthermore, personality styles and the level of structural integration of personality are, as well, related to severity and to the response to treatment. For this reason, in order to assess complex depression and to improve treatment, it is important to deepen our understanding of the interaction of depression and personality. We examine this issue from the perspective of functional domains that are differentially affected in depression concurrent with personality dysfunction and specific personality styles, as well as how the co-occurrence of both impacts on the severity of the condition. The chapter outlines the complex and multimodal relationships between depression and personality dysfunction, discussing specific models for the interaction between depression and borderline personality disorder, on one hand, and personality styles and structural personality integration, on the other hand.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Depression

- Personality disorders

- Personality dysfunction

- Intermediate phenotypes

- Personality styles

- Complex depression

1.1 Introduction

Due to its high lifetime prevalence worldwide (10–15% of the population; Lépine & Briley, 2011) and high subjective and societal costs, major depressive disorders (MDD) need to be better understood. When depression is severe and long-lasting, it results in intense suffering for affected individuals, and also for their loved ones, leading as well to a significant decline in social and vocational functioning. Depression increases the risk for suicidality, comorbidity with other mental health conditions, and chronic physical illness and impairs physical and psychosocial functioning (Spijker, van Straten, Bockting, Meeuwissen, & van Balkom, 2013). Additionally, depression is a recurrent illness (DeRubeis, Siegle, & Hollon, 2008), with 50–60% of patients experiencing a second episode, 70% of these a third one, and 90% of these a fourth episode (Hart, Craighead, & Craighead, 2001). This means that many patients with this disorder spend up to 21% of their lives clinically depressed (Vos et al., 2004). Treating depression is a worldwide priority, but treatment effectiveness needs to be improved because only 30–40% of patients enrolled in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) show remission of symptoms (Craighead & Dunlop, 2014).

Further research in depression is urgent to improve detection and treatment of those affected. However, depression is a heterogeneous clinical phenomenon (Buch & Liston, 2020), presenting itself very differently across individuals and probably stemming from differential etiopathogenetic mechanisms (Cai, Choi, & Fried, 2020). This heterogeneity may be partially responsible for lack of substantive progress in treatment effectiveness. The interaction between depression and personality dysfunction is one domain suitable to parse out some aspects of the heterogeneity of depression. The term complex depression has been proposed by our group to understand depressive presentations that are further complicated by personality dysfunction (Behn, 2019). Nowadays the term has been extended to include other conditions that add severity to the course of the disorder and imply difficulties for its treatment, such as psychosocial stressors, early life maltreatment, risk of suicide, conditions related to the health system, and treatment, which is addressed throughout this book.

In this chapter complex depression will be examined through the lens of functional domains related to personality functioning, namely, affect regulation, identity, self and other regulation, socio-cognitive functioning, self-criticism (a form of self-dysregulation particularly important in depression), and neurobiological underpinnings related to depression complicated by personality dysfunction.

Generally speaking, complexity in mental health problems refers to the aggregation of difficulties or affected domains on top of the presenting problem (e.g., depression) and it refers to an intrinsically multidimensional construct, because depression can be complicated by comorbid mental health disorders. For the purposes of this chapter, complexity is restricted to the interaction between depressive symptomatology (i.e., a depressive phenotype) and personality dysfunction, including a dimensional component that admits subthreshold or mild personality dysfunction and a categorical component indicative of the presence of a personality disorder. Regarding the latter, we will focus on borderline personality disorder (BPD) because this disorder concentrates most of the empirical research on personality pathology, and thus, more robust conclusions can be drawn from the depression and personality disorders literature. We will also examine personality styles as related to specific depressive phenotypes and personality structural integration.

1.2 The Overlap Between Depression and Personality Dysfunction in Classification Systems

The interaction between depression and personality functioning is relevant for the scientific understanding of the heterogeneity and complexity of depression as well as for the improvement of treatment options. Before we delve into co-occurrence or mutual influence models between both disorders, it is useful to discuss the general problem of symptomatic superposition between depression and personality pathology and the diagnostic difficulties that emerge.

The debate regarding a strict separation versus the superposition between depression and personality disorders is not new. In the 1960s Akiskal and McKinney (1973) argued in a widely cited study published in Science that depression is a single and stable clinical entity with strong diagnostic borders with other clinical entities. This may be considered a strong positioning regarding the borders with all other diagnostic entities from the mood disorders specialist perspective of the time. On the other hand, Gunderson and Phillips (1991) have argued that BPD, the most prototypical personality disorder, exhibits a weak and nonspecific relationship to depression. Both perspectives, one stemming from the mood disorders field and the other from de BPD field, are examples of the notion that both disorders are quite different clinical entities with robust diagnostic borders. Furthermore, both perspectives assume that depression and personality disorders are distinct clinical entities that can be clearly differentiated at the phenotypic and at the etiological level. Yet, very frequently, both disorders present together. As a way to bridge this gap and achieve common ground, Klein and colleagues (Klein, Kotov, & Bufferd, 2011) proposed that even though different at the level of its manifest clinical presentations (phenotype), both entities may share common causes, that is, common etiological pathways or affected functional domains. These common etiological pathways can also include intermediate phenotypes that mediate between genomic and symptomatic complexity. Indeed, the notion of an intermediate phenotype may be a key component in understanding how depression and personality disorders are deeply intertwined. Above and beyond the discussion regarding diagnostic limits or superposition of diagnostic entities, we make the argument that studying key functional domains related to personality functioning is a useful approach to examine specific intermediate phenotypes involved in depression heterogeneity. These domains refer to psychological mechanisms related to phenotypic complexity. Intermediate phenotypes could be crucial for the understanding of the complex relationship between depression and personality dysfunction because both disorders are “superficially divergent [but] fundamentally overlapping” (Choi-Kain & Gunderson, 2015, p. 257). Mapping intermediate phenotypes related to both depression and personality disorders is also a viable strategy to improve treatment effectiveness.

Following this reasoning, phenotypic variability can be reconducted to common or overlapping intermediate phenotypes, within specific affected functional domains. Functional domains can cover several intermediate phenotypes. In other words, a particular functional domain affected in depression and BPD, for example, emotional regulation, can contain several different intermediate phenotypes, including negative mood bias or amygdala dysfunction. This view does not suppose direct causal influences between depression and personality dysfunction, but rather, common disease mechanisms within functional domains. Patients frequently present both disorders because they have similar causal influences, but a patient’s depression is not caused by his or her personality problems (Behn, Herpertz, & Krause, 2018). Following this idea, major depressive disorder and BPD can be understood as two distinct disorders, sharing common affected functional domains, regardless of specific phenotypes (Goodman, Chowdhury, New, & Siever, 2015).

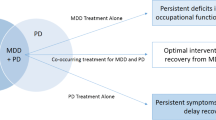

1.3 Depression and Personality Disorders

The comorbidity of depression and personality disorders is a common clinical finding. In a meta-analysis, Friborg et al. (2014) estimated that 45% of patients with major depressive disorder had a concurrent personality disorder, while approximately 60% of patients with a diagnosis of personality disorder also were diagnosed with a depressive disorder. This concurrent presentation has shown to be predictive of more persistent and recurrent depressive episodes (Levenson, Wallace, Fournier, Rucci, & Frank, 2012; Skodol et al., 2011) and related, as well, to an increased probability of psychiatric admissions (Wiegand & Godemann, 2017). Thus, personality dysfunction combined with depressive presentations is not only quite common, but it also results in more complex and severe psychopathology, which obviously has a bearing in prognosis and treatment planning. Additionally, patients with comorbid depressive disorder and personality disorders have typically poorer adherence to treatments and respond worse to antidepressant psychotherapy compared to those patients with a single diagnosis of depression (Newton-Howes et al., 2014). The psychosocial and occupational impairment is also higher for patients with comorbid depression and personality pathology (Markowitz, Skodol, & Bleiberg, 2006) and they have a higher risk of developing additional psychopathology, for example, anxiety (Stein, Hollander, & Skodol, 1993).

For those patients with comorbid depression and BPD, depressive symptomatology is also typically more severe when compared to depressed controls (Köhling et al., 2016). Furthermore, the specificity of concurrent depression and BPD has been explored in depth in a meta-analysis developed by Köhling, Ehrenthal, Levy, Schauenburg, and Dinger (2015). This concurrent presentation is characterized by increased anger and hostility that can be directed also against the self, resulting in increased self-criticism, an aspect previously proposed by Blatt and Zuroff (1992). The functional domain of affect regulation is affected in both, MDD and BPD; however the interaction between this functional domain and the functional domain of social relationships explains some differences between both disorders, where affect dysregulation in BPD with MDD appears to be significantly more reactive to real or perceived interpersonal rejection than in MDD alone (Goodman, New, Triebwasser, Collins, & Siever, 2010). Affected functional domains of impulsivity within depression seem to be mostly indicative of complex depression, including a greater risk for self-injurious behavior and suicidality (Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan, & Bohus, 2004).

The use of Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) (Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008) has been crucial to further understand these intertwined disease mechanisms at the intermediate phenotype level. A study using this methodology found that patients presenting MDD alone compared to those with MDD and BPD did not exhibit differential patterns of affect dysregulation but were indeed distinguished by interpersonal reactivity (Köhling et al., 2016). Even though it is possible that in this specific study EMA calibration was not intense enough to detect differences between both groups in patterns of affect dysregulation, results are still quite interesting and suggestive. In fact, mood disturbances in depression have been largely considered to be episodic, more sustained, and less reactive to environmental interpersonal stressors. Conversely, in BPD, affect dysregulation has been typically considered to be chronic rather than episodic and is characterized by intense fluctuations and extremely high reactivity to interpersonal stressors, most notably to interpersonal rejection and abandonment (Staebler, Helbing, Rosenbach, & Renneberg, 2011). It is only due to the publication of long-term longitudinal studies that these assumptions regarding stark differences can be looked at critically. According to this literature, depression frequently exhibits a recurrent course and inter-episodic maintenance of residual symptoms is quite common (Frodl, Möller, & Meisenzahl, 2008). According to Klein (2010), when depression exhibits an early onset, it is characterized by significant impairment in interpersonal functioning, comparable to BPD, and most likely related to personality dysfunction (Herpertz, Steinmeyer, & Saß, 1998). On the other hand, according to longitudinal studies, some of them spanning decades, BPD patients typically lose their most intense, diagnostic threshold symptomatology with the passage of time (Zanarini, 2018). When remission occurs in BPD, it is very likely to be sustained across measurement waves in longitudinal studies, thus exhibiting even less recurrence than common depression (Paris & Zweig-Frank, 2001).

1.4 Functional Domains Implicated in Depression and Personality Dysfunction

Personality functioning includes multiple psychological and neurobiological domains operating in an integrated way. These systems include cognitive functioning and identity, affect regulation, behavioral control, and interpersonal functioning. Such functional domains may include several intermediate phenotypes and define personality pathology in recent classifications, including DSM-5 Alternative Model and the new ICD-11 classification. In fact, specific phenotypes for personality disorders (e.g., narcissistic, histrionic, schizoid, etc.) are dropped altogether in ICD-11 in favor of a single diagnosis of personality disorder based on deficits in self and interpersonal functioning. Only BPD is retained as a qualifier, likely because of insurance coverage issues (Herpertz et al., 2017). Crucial to these new diagnostic models is the dimensional conceptualization of personality dysfunction in a gradient of severity. Based on the assessment of functional domains, the clinician needs to decide whether or not a personality disorder is present and then estimate the severity. A careful evaluation of the level of the personality dysfunction within a continuum of severity is proposed by current diagnostic guidelines, including the ICD-11 and the DSM-5 Alternative Model. Dimensionality is thus a key component in the functional domains perspective, and even sub-threshold personality vulnerabilities need to be taken into account as they can complicate depression and result in chronicity or recurrence, as well as on early onset and resistance to treatment as usual for common depression (Newton-Howes et al., 2014). Variability in deficits of functional domains implicated in complex depression may result in different phenotypes diagnostically and, clinically, allows to tailor interventions in order to prioritize treatment of most affected functional domains. As an example, a depressed patient with increased behavioral dysregulation possibly related to the functional domain of impulsivity will require treatment alternatives that mainly focus on this domain, for example, skills training in the context of dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT). On the other hand, a patient with no behavioral dysregulation but prominent affectation of the functional domain of identity (e.g., lack of self-concept clarity and self-direction) will likely benefit from treatment alternatives that improve identity functioning, for example, components of transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP). This diverse and patient-centered approach has been advanced, for example, in the setting of integrated modular treatments (Livesley, Dimaggio, & Clarkin, 2015).

Several domains of functioning related to personality dysfunction can further complicate depressive symptomatology and thus benefit from a functional domains perspective for diagnosis and treatment planning. An excellent although not recent review by Hasler, Drevets, Manji, and Charney (2004) presents specific intermediate phenotypes for depression, including mood bias towards negative emotions, impaired reward functioning, impaired learning and memory, and increased stress sensitivity. Goodman et al. (2010) have summarized this literature specifically comparing BPD with MDD and focusing primarily on shared biological endophenotypes. A recent meta-analysis reviews one of the main neurobiological endophenotypes related to BPD, namely, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis which may help explain stress-related symptoms. Specific functional domains related to self and other functioning include metacognitive capacities related to the understanding of self-states and empathy (Dimaggio & Brüne, 2016); difficulties related to hypermentalizing, particularly in the context of intimate relationships (Sharp et al., 2016); and insecure attachment styles (Bo & Kongerslev, 2017). From a trait perspective, interpersonal hostility, rejection sensitivity, and low agreeableness have also been identified as components of personality dysfunction implicated in complex depression (Hirsch, Quilty, Bagby, & McMain, 2012; Zufferey, Caspar, & Kramer, 2019). Intense mental pain, although present in BPD and MDD, appears to be particularly reactive to interpersonal rejection in BPD (Fertuck, Karan, & Stanley, 2016). Emotion dysregulation has been prominently related to personality dysfunction, particularly in patients with BPD (Dixon-Gordon, Peters, Fertuck, & Yen, 2017) with relatively well-known neurobiological underpinnings as indicated in a fairly recent meta-analysis (Schulze, Schmahl, & Niedtfeld, 2016). Within the functional domain of affect regulation, specific intermediate phenotypes can be further identified, including difficulties in emotional awareness (De Panfilis, Ossola, Tonna, Catania, & Marchesi, 2015) and emotional expression and modulation (Berenson, Downey, Rafaeli, Coifman, & Paquin, 2011; Mancke, Herpertz, Kleindienst, & Bertsch, 2017). The functional domain of self and cognitive processes has been related to specific biases for negative information processing as well as binary, “black or white” thinking (Kramer, Vaudroz, Ruggeri, & Drapeau, 2013).

1.5 Depression, Personality Styles, and Structural Personality Integration

In 1974 Sydney Blatt proposed that depression may be a by-product of deficits in the structure of object relations, developing the idea of two distinct forms of depression (Blatt, 1974, 2004, 2008). These forms of depression would be anchored in personality styles, implying dysfunction in different dimensions. The different personality styles would emerge from two main developmental tasks: self-definition and relatedness. As a result, depression could be conceptualized as the consequence of disruptions in the course of these developmental tasks, leading to two different forms of depression: introjective and anaclitic. Introjective depression would show deficits in self-integrity and in self-esteem (typically extreme self-criticism; Blatt & Zuroff, 1992), whereas anaclitic depression would be characterized by a disruption of interpersonal relatedness (typically fears of abandonment). The self-critical (introjective) and dependent (anaclitic) types of depression have been measured through the Depressive Experience Questionnaire (DEQ; Blatt, D’Afflitti, & Quinlan, 1976; Blatt, Zohar, Quinlan, Zuroff, & Mongrain, 1995).

These different types of depression have been studied from the perspective of neurophysiological, psychological, and psychosocial variables (de la Parra, Dagnino, Valdés, & Krause, 2017). Silva, Vivanco-Carlevari, Barrientos, Martinez, Salazar and Krause (2017) provided experimental evidence indicating that biological stress reactivity (cortisol in saliva) of individuals is modulated by their positioning within the anaclitic or introjective polarity, with self-critical individuals exhibiting more objective biological stress reactivity compared to dependent individuals, but anaclitics showing higher scores in self-report instruments. Thus, personality predispositions in the anaclitic versus introjective continuum could indicate a specific vulnerability for the development of depression, particularly when an individual is confronted with stressors. Rodríguez et al. (2017) studied the dependent versus self-critical functioning in relation to cognitive tasks and mentalization, finding longer reaction times in cognitive tasks for dependent individuals, and a poorer performance in mentalization for high self-critical individuals.

On the dimension of psychological variables, Dagnino, Pérez, Gómez, Gloger, and Krause (2017) reported differences in attachment between introjective and anaclitic participants. While introjective depressive patients showed higher anxious and avoidant attachment, anaclitic patients only showed anxious attachment. In this study, likewise previously mentioned by Rodríguez et al. (2017), higher levels of self-criticism go along with more depressive symptomatology. In psychotherapy, introjective patients are more likely to drop out from treatment, and those that complete treatment show less improvement in depressive symptoms, compared to anaclitic participants (de la Parra et al., 2017). Similar results have also been observed in psychosocial interventions (Olhaberry et al., 2015), with less improvement of maternal depression and higher avoidant and anxious attachment scores in self-critical participants. On the basis of these findings, it can be stated that the introjective personality style adds severity to depression and complexity for its treatment.

A relevant question is how these personality styles relate to personality structural functioning, as it is understood from the perspective of the Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnosis System (OPD Task Force, 2008), implying the availability of mental functions for the regulation of the self and its relationships with others. Five levels of structural integration are defined by the degree of availability of these mental functions, within a continuum, including high integration (level 1), moderate integration (level 2), low integration (level 3), and disintegration (level 4) (de la Parra et al., 2017). A self-rating questionnaire was developed to assess these structural levels in research settings (OPD Structure Questionnaire, OPD-SQ, Schauenburg et al., 2012).

Research with the OPD system has shown that lower structural levels in personality functioning go along with higher mental health symptomatology (Zimmermann et al., 2012). Relating structural functioning to personality styles, Dagnino (2015) found that high self-criticism was associated with less integrated structural functioning, measured by the OPD system. Following this line of research, de la Parra et al. (2017) studied structural personality functioning (measured by the OPD) and personality styles (measured by the DEQ) in clinical and nonclinical samples. Their results show, first, that lower structural levels in personality functioning were related to higher levels of depressive symptomatology and, additionally, that the correlation between self-criticism and structural functioning was significantly higher than between dependency and structural functioning.

These studies give support to the hypothesis that personality styles related to depression are not independent from structural personality functioning. Furthermore, they support the idea that both, the self-critical personality style and the lower integration of structural functioning, add complexity to depression. Therefore, both models can be useful to untangle aspects of the heterogeneity of depression that have to be taken into account in research and for treatment efficacy.

1.6 Conclusions

This chapter approached the topic of complex depression from the review of the literature regarding the interaction of depression and personality dysfunction with the aim of contributing to a better understanding of the heterogeneity of depression. It is an empirical and clinical fact that depression is a notoriously heterogeneous clinical syndrome, and this heterogeneity can be established at an empirical and conceptual level by taking into consideration personality. We have shown that patients who, in addition to a depression, present personality dysfunction are more than twice as likely to be nonresponsive to treatment compared to patients with common, stand-alone depression. We have advanced the idea that a functional domains perspective provides adequate coverage of personality functioning and can work as a framework for the identification of specific affected intermediate phenotypes that contribute complexity in depression.

Nevertheless, there is an ongoing debate about the symptomatic superposition between depression and personality pathology, which we addressed in the first section of this chapter. The different positions argue in favor of a strict separation versus the superposition between depression and personality disorders. This debate can be addressed with the inclusion of a common cause hypothesis at the level of shared affected intermediate phenotypes within functional domains.

In the next section, we reviewed findings about the comorbidity of depression and personality disorders, which lies around between 45% (patients with major depressive disorder diagnosed also with a personality disorder) and 60% (patients with a personality disorder that also were diagnosed with a depressive disorder). Personality dysfunction combined with depression is not only common, but results in more severe psychopathology and poorer adherence to treatments. We have argued that, from a functional domains perspective, comorbidity estimates are highly likely because of shared affected intermediate phenotypes, in particular the functional domain of affect regulation and modulation.

In the third section of this chapter, we proposed that underlying functional domains related to personality functioning would be a useful approach to examine specific intermediate phenotypes involved in depression heterogeneity. These intermediate phenotypes could be crucial for the understanding of the complex relationship between depression and personality dysfunction and also be a viable strategy to improve treatment effectiveness. Symptom heterogeneity can be vast, but vulnerability in relevant functional domains can reduce this heterogeneity and be an important input for treatment design, specifically for the development of differential treatment components for patients that share these affected intermediate phenotypes.

With the idea that even sub-threshold personality vulnerabilities need to be taken into account, as they can complicate depression, we devoted the fourth section of this chapter to two conceptual models of personality functioning, with their corresponding empirical research, including Sydney Blatt’s polarity of relatedness and self-definition in personality development, resulting in different personality styles and different types of depression, and the model of levels of structural personality integration, proposed the OPD task group. Interestingly, research findings for both models establish the relationship between personality and severity of depression. In Blatt’s model the higher impairment in self-definition adds severity to depression; in the OPD model’s case, lower levels of personality integration are related to more complex and severe depressive presentations.

In conclusion, the evidence we presented along this chapter indicates that personality disorders and dysfunctions, personality styles, as well as the level of structural integration of personality, add severity to depression and lead to a poorer response to habitual treatments. For this reason, personality is a crucial dimension for explaining severe depression, and a functional domain perspective is a useful framework to address research, diagnosis, and treatment planning. This understanding is the basis for the development of detection strategies and treatments designed specifically to address personality dysfunctions and styles that are responsible for the poor outcome of standard interventions in cases of complex depression.

References

Akiskal, H. S., & McKinney, W. T. (1973). Depressive disorders: Toward a unified hypothesis: Clinical, experimental, genetic, biochemical, and neurophysiological data are integrated. Science, 182(4107), 20–29.

Behn, A. (2019). Working with clients at the intersection of depression and personality dysfunction: Scientific and clinical findings regarding complex depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(5), 819–823.

Behn, A., Herpertz, S. C., & Krause, M. (2018). The interaction between depression and personality dysfunction: State of the art, current challenges, and future directions. Introduction to the Special Section. Psykhe, 27(2), 1–12.

Berenson, K. R., Downey, G., Rafaeli, E., Coifman, K. G., & Paquin, N. L. (2011). The rejection–rage contingency in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(3), 681.

Blatt, S. J. (1974). Levels of object representation in anaclitic and introjective depression. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 29, 107–157.

Blatt, S. J. (2004). Experiences of depression: Theoretical, clinical and research perspectives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Blatt, S. J. (2008). Two primary configurations of psychopathology. In S. Blatt (Ed.), Polarities of experiences: Relatedness and self-definition in personality development, psychopathology and the therapeutic process (pp. 234–245). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Blatt, S. J., D’Afflitti, J. P., & Quinlan, D. M. (1976). Experiences of depression in normal young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85, 383–389.

Blatt, S. J., & Zuroff, D. C. (1992). Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition: Two prototypes for depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 12, 527–562.

Blatt, S. J., Zohar, A. H., Quinlan, D. M., Zuroff, D. C., & Mongrain, M. (1995). Subscales within the dependency factor of the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 64(2), 319–339.

Bo, S., & Kongerslev, M. (2017). Self-reported patterns of impairments in mentalization, attachment, and psychopathology among clinically referred adolescents with and without borderline personality pathology. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 4(1), 4.

Buch, A. M., & Liston, C. (2020). Dissecting diagnostic heterogeneity in depression by integrating neuroimaging and genetics. Neuropsychopharmacology, 46, 1–22.

Cai, N., Choi, K. W., & Fried, E. I. (2020). Reviewing the genetics of heterogeneity in depression: Operationalizations, manifestations, and etiologies. Human Molecular Genetics. Ahead of Print. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddaa115.

Choi-Kain, L. W., & Gunderson, J. G. (2015). Conclusion: Integration and synthesis. In Borderline personality and mood disorders (pp. 255–270). New York, NY: Springer.

Craighead, W. E., & Dunlop, B. W. (2014). Combination psychotherapy and antidepressant medication treatment for depression: For whom, when, and how. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 267–300.

Dagnino, P. (2015). Structural vulnerabilities of depression. In Millennium nucleus research program “psychological intervention and change in depression” meeting. Santiago, Chile: Universidad de Chile.

Dagnino, P., Pérez, C., Gómez, A., Gloger, S., & Krause, M. (2017). Depression and attachment: How do personality styles and social support influence this relation? Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 20, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2017.237

de la Parra, G., Dagnino, P., Valdés, C., & Krause, M. (2017). Beyond self-criticism and dependency: Structural functioning of depressive patients and its treatment. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 20, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2017.236

De Panfilis, C., Ossola, P., Tonna, M., Catania, L., & Marchesi, C. (2015). Finding words for feelings: The relationship between personality disorders and alexithymia. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 285–291.

DeRubeis, R. J., Siegle, G. J., & Hollon, S. D. (2008). Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: Treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(10), 788–796.

Dimaggio, G., & Brüne, M. (2016). Dysfunctional understanding of mental states in personality disorders: What is the evidence? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 64, 1–3.

Dixon-Gordon, K. L., Peters, J. R., Fertuck, E. A., & Yen, S. (2017). Emotional processes in borderline personality disorder: An update for clinical practice. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 27(4), 425.

Fertuck, E. A., Karan, E., & Stanley, B. (2016). The specificity of mental pain in borderline personality disorder compared to depressive disorders and healthy controls. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 3(1), 2.

Friborg, O., Martinsen, E. W., Martinussen, M., Kaiser, S., Øvergård, K. T., & Rosenvinge, J. H. (2014). Comorbidity of personality disorders in mood disorders: A meta-analytic review of 122 studies from 1988 to 2010. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152, 1–11.

Frodl, T., Möller, H. J., & Meisenzahl, E. (2008). Neuroimaging genetics: New perspectives in research on major depression? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 118(5), 363–372.

Goodman, M., Chowdhury, S., New, A. S., & Siever, L. J. (2015). Depressive disorders in borderline personality disorder: Phenomenology and biological markers. In Borderline personality and mood disorders (pp. 13–37). New York, NY: Springer.

Goodman, M., New, A. S., Triebwasser, J., Collins, K. A., & Siever, L. (2010). Phenotype, endophenotype, and genotype comparisons between borderline personality disorder and major depressive disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 24(1), 38–59.

Gunderson, J. G., & Phillips, K. A. (1991). A current view of the interface between borderline personality disorder and depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(8), 967–975.

Hart, A. B., Craighead, W. E., & Craighead, L. W. (2001). Predicting recurrence of major depressive disorder in young adults: A prospective study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(4), 633.

Hasler, G., Drevets, W. C., Manji, H. K., & Charney, D. S. (2004). Discovering endophenotypes for major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 29(10), 1765–1781.

Herpertz, S. C., Huprich, S. K., Bohus, M., Chanen, A., Goodman, M., Mehlum, L.,... & Sharp, C. (2017). The challenge of transforming the diagnostic system of personality disorders. Journal of personality disorders, 31(5), 577–589.

Herpertz, S., Steinmeyer, E. M., & Saß, H. (1998). On the conceptualisation of subaffective personality disorders. European Psychiatry, 13(1), 9–17.

Hirsch, J. B., Quilty, L. C., Bagby, R. M., & McMain, S. F. (2012). The relationship between agreeableness and the development of the working alliance in patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 26(4), 616–627.

Klein, D. N. (2010). Chronic depression: diagnosis and classification. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(2), 96–100.

Klein, D. N., Kotov, R., & Bufferd, S. J. (2011). Personality and depression: Explanatory models and review of the evidence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 269–295.

Köhling, J., Ehrenthal, J. C., Levy, K. N., Schauenburg, H., & Dinger, U. (2015). Quality and severity of depression in borderline personality disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 13–25.

Köhling, J., Moessner, M., Ehrenthal, J. C., Bauer, S., Cierpka, M., Kämmerer, A., … Dinger, U. (2016). Affective instability and reactivity in depressed patients with and without borderline pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30(6), 776–795.

Kramer, U., Vaudroz, C., Ruggeri, O., & Drapeau, M. (2013). Biased thinking assessed by external observers in borderline personality disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 86(2), 183–196.

Lépine, J. P., & Briley, M. (2011). The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 7(Suppl 1), 3.

Levenson, J. C., Wallace, M. L., Fournier, J. C., Rucci, P., & Frank, E. (2012). The role of personality pathology in depression treatment outcome with psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 719–729. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029396

Lieb, K., Zanarini, M. C., Schmahl, C., Linehan, M. M., & Bohus, M. (2004). Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet, 364(9432), 453–461.

Livesley, W. J., Dimaggio, G., & Clarkin, J. F. (Eds.). (2015). Integrated treatment for personality disorder: A modular approach. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Mancke, F., Herpertz, S. C., Kleindienst, N., & Bertsch, K. (2017). Emotion dysregulation and trait anger sequentially mediate the association between borderline personality disorder and aggression. Journal of Personality Disorders, 31(2), 256–272.

Markowitz, J. C., Skodol, A. E., & Bleiberg, K. (2006). Interpersonal psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Possible mechanisms of change. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 431–444.

Newton-Howes, G., Tyrer, P., Johnson, T., Mulder, R., Kool, S., Dekker, J., & Schoevers, R. (2014). Influence of personality on the outcome of treatment in depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28, 577–593.

Olhaberry, M., Mena, C., Zapata, J., Miranda, A., Romero, M., & Sieverson, C. (2015). Terapia de interacción guiada en díadas madre-bebé con sintomatología depresiva materna en el embarazo: un estudio piloto. [Guided interaction therapy in mother-baby dyads with maternal depressive symptomatology in pregnancy: A pilot study]. Summa Psicológica UST, 12(2), 63–74.

OPD Task Force (Ed.). (2008). Operationalized psychodynamic diagnosis OPD-2: Manual of diagnosis and treatment planning. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe Publishing.

Paris, J., & Zweig-Frank, H. (2001). The 27-year follow-up of patients with borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 42(6), 482–487.

Rodríguez, E., Ruiz, J. C., Valdés, C., Reinel, M., Díaz, M., Flores, J., … Tomicic, A. (2017). Estilos de personalidad dependiente y autocrítico: desempeño cognitivo y sintomatología depresiva [Dependent and self-critical personality styles: Cognitive performance and depressive symptomatology]. Latinoamericana de Psicología, 49, 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rlp.2016.09.005

Schauenburg, H., Dinger, U., Komo-Lang, M., Klinkerfuss, M., Horsch, L., Grande, T., & Ehrenthal, J. C. (2012). Der OPD Strukturfragebogen [The OPD structure questionnaire]. In S. Döring & S. Hörz (Eds.), Handbuch der Strukturdiagnostik (pp. 284–307). Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer.

Schulze, L., Schmahl, C., & Niedtfeld, I. (2016). Neural correlates of disturbed emotion processing in borderline personality disorder: A multimodal meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry, 79(2), 97–106.

Sharp, C., Venta, A., Vanwoerden, S., Schramm, A., Ha, C., Newlin, E., … Fonagy, P. (2016). First empirical evaluation of the link between attachment, social cognition and borderline features in adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 64, 4–11.

Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A., & Hufford, M. R. (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 1–32.

Silva, J. R., Vivanco-Carlevari, A., Barrientos, M., Martínez, C., Salazar, L. A., & Krause, M. (2017). Biological stress reactivity as an index of the two polarities of the experience model. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 84, 83–86.

Skodol, A. E., Grilo, C. M., Keyes, K. M., Geier, T., Grant, B. F., & Hasin, D. S. (2011). Relationship of personality disorders to the course of major depressive disorder in a nationally representative sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(3), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050695

Spijker, J., van Straten, A., Bockting, C. L., Meeuwissen, J. A., & van Balkom, A. J. (2013). Psychotherapy, antidepressants, and their combination for chronic major depressive disorder: a systematic review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(7), 386–392.

Staebler, K., Helbing, E., Rosenbach, C., & Renneberg, B. (2011). Rejection sensitivity and borderline personality disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(4), 275–283.

Stein, D. J., Hollander, E., & Skodol, A. E. (1993). Anxiety disorders and personality disorders: A review. Journal of Personality Disorders, 7(2), 87–104.

Vos, T., Haby, M. M., Barendregt, J. J., Kruijshaar, M., Corry, J., & Andrews, G. (2004). The burden of major depression avoidable by longer-term treatment strategies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(11), 1097–1103.

Wiegand, H. F., & Godemann, F. (2017). Increased treatment complexity for major depressive disorder for inpatients with comorbid personality disorder. Psychiatric Services, 68(5), 524–527.

Zanarini, M. C. (2018). In the fullness of time: Recovery from borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Zimmermann, J., Ehrenthal, J. C., Cierpka, M., Schauenburg, H., Doering, S., & Benecke, C. (2012). Assessing the level of structural integration using operationalized psychodynamic diagnosis (OPD): Implications for DSM-5. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94, 522–532.

Zufferey, P., Caspar, F., & Kramer, U. (2019). The role of interactional agreeableness in responsive treatments for patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 33(5), 691–706.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the ANID-Millennium Science Initiative/Millennium Institute for Research on Depression and Personality-MIDAP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Krause, M., Behn, A. (2021). Depression and Personality Dysfunction: Towards the Understanding of Complex Depression. In: de la Parra, G., Dagnino, P., Behn, A. (eds) Depression and Personality Dysfunction. Depression and Personality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70699-9_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70699-9_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-70698-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-70699-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)