Abstract

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the main cause of death from cancer among women in Europe and worldwide. The third cycle of the CONCORD programme found wide global differences in five-year net survival for women with breast cancer, both between countries and over time. Survival from breast cancer is higher for more affluent women than more deprived women. Patient and tumour characteristics, factors related to the healthcare system and to the wider social environment may explain some of these socioeconomic differences.

A literature search was conducted to investigate the state of the art on this topic. We selected 42 of 648 articles published in the 10 years up to December 2019 that included results on socioeconomic differences in survival. These inequalities remain after controlling for stage at diagnosis, treatment, hormonal receptors, the woman’s lifestyle, comorbidities at diagnosis and screening attendance. Factors that contribute to socioeconomic inequalities in survival include primary care consultation patterns, symptomatic presentation, the time interval between the first report of symptoms and the eventual diagnosis, and the interval between diagnosis and the start of treatment. Social interactions with and support from friends and family also play a role.

Deeper insight into the complex inter-relation between these factors and breast cancer survival is required. New studies should include as many factors as possible, especially in those European countries where the impact of socioeconomic status on breast cancers survival has never been considered.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the main cause of death from cancer among women in Europe and worldwide (Bray et al. 2018).

The third cycle of the CONCORD programme (CONCORD-3) updated the global surveillance of cancer survival to include patients diagnosed during the 15-year period from 2000–2014 with one of 18 malignancies, including breast cancer. It included individual data on more than 37.5 million cancer patients from 322 population-based cancer registries in 71 countries and territories worldwide (Allemani et al. 2018). The main outcome measure was five-year net survival: this is the cumulative probability of surviving at least 5 years from diagnosis, after correction for mortality due to other causes of death. Net survival is usually expressed as a percentage for convenience.

The results show that five-year net survival for adult women (aged 15–99 years) diagnosed with breast cancer has varied widely in Europe, both between countries and over time. Age-standardised five-year net survival for women diagnosed during 2000–2004 ranged from 65% (95% confidence interval [CI] 63–66%) in Lithuania to 87% (83–92%) in Iceland. For women diagnosed 10 years later, during 2010–2014, the range was from 71% (69–72%) in the Russian Federation to 89% (85–93%) in Iceland (Allemani et al. 2018).

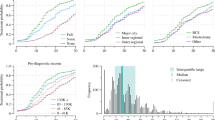

CONCORD-3 also showed that survival varies widely within countries, although in most countries, these regional differences have narrowed over time (Fig. 7.1). Germany, France, Italy and the United Kingdom are exceptions. In these countries, regional variation in five-year net survival for women diagnosed during 2010–2014 had changed very little from the variation seen among women diagnosed during 2000–2004.

These data reveal wide disparities in breast cancer outcomes across Europe. Population-based cancer survival is a key indicator of the overall effectiveness of health systems in managing care and treatment for all cancer patients. However, there are significant inequalities in the availability of and access to high-quality cancer care (Aapro et al. 2017). The inequalities in cancer survival arise within societies.

The determinants of population-based cancer survival differences can be divided into two groups. Factors related to the social environment include the availability and organisation of diagnostic facilities, organised mass screening, adequate treatment facilities, and sufficient numbers of doctors and other health personnel. Factors related to the individual cancer patient include socioeconomic status, serious concomitant disease at diagnosis [comorbidity], lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol use and physical activity, and race/ethnicity (Sant et al. 2015).

A worldwide review of all cancers in the late 1990s found that patients in lower social classes had consistently lower survival than those in higher social classes (Kogevinas and Porta 1997). A more recent worldwide review found that part of the association between socioeconomic groups and cancer survival is attributable to unfavourable stage distribution at diagnosis and lower access to optimal treatment (Woods et al. 2006). However, the authors underlined that more investigations were needed: (i) on patients characteristics, such as nutrition and comorbidities that may interact with treatment decisions and with the outcome; and (ii) on how socioeconomic differences are associated with access to health services, participation in screening programmes and, ultimately, to differences in cancer survival.

We conducted a PubMed literature search to investigate the current state of the art on this topic. The search terms used were designed to identify references that indexed or mentioned: (i) breast cancer, (ii) survival, (iii) a European country and (iv) socioeconomic or social status, or their synonyms. All European countries were included as search terms. Only articles published in the 10 years up to December 2019 and explicitly showing results on socioeconomic differences in survival were selected.

Literature Review

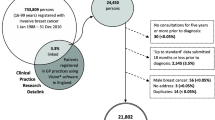

We selected 648 articles for abstract review, of which 144 were selected for full-text review (flow chart in Fig. 7.2). Of these, 42 were finally included in our review. The studies varied widely in the calendar period of diagnosis examined, as well as the sample size, statistical methods, definition of socioeconomic status and the co-variables included in the analyses, as well as between the countries included. The main results and key descriptors are summarised in Table 7.1.

Thirty-three studies (79%) were conducted in Northern Europe (Denmark, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, UK), five (12%) in Central Europe (France, Switzerland) and three (7%) in Southern Europe (Italy). One study involved 21 countries.

Most studies used population-based cancer registry data, together with information from national statistics databases. Only one study used information from hospital databases (Baker et al. 2010).

Crude survival estimates (e.g. survival from cancer or all causes of death combined) or hazard ratios were provided by 20 studies. Twenty-two studies presented either net or relative survival estimates, or the relative excess risk of death (sometimes called excess hazard rate ratios). Five studies only provided the number of avoidable deaths or the average loss in life expectancy, estimated with regression survival models.

Survival was examined in relation to various indices of socioeconomic status. Ten studies used education level, home ownership or household income. Three studies considered occupational group or type of employment, but most studies considered tertiles, quintiles or deciles of a socioeconomic status score, usually based on summaries of individual fiscal data for residents in a given area and assigned to each patient living in that area, using her postcode of residence at diagnosis. The scores of socioeconomic status were derived with different variables in each country, typically income and occupation, but sometimes educational level, home rental or ownership status, the economic value of the home, the social class or the civil status (single, married, divorced, etc.).

Differences between the studies were also evident in the additional variables investigated to assess socioeconomic differences in survival. Some studies only reported results on socioeconomic differences in survival, overall or over time. Others considered the age of the women at diagnosis, the tumour stage at diagnosis, tumour characteristics (e.g. histology or hormonal status), and modality of cancer detection (screen-detected vs. non-screen detected). Comorbidities were analysed with or without lifestyle factors. Other studies also investigated treatments or the familial and social environment.

In line with the results for all cancers combined, survival from breast cancer was higher for less deprived (more affluent) women than more deprived women at 1, 5 and 10 years after diagnosis (Belot et al. 2018). However, although survival has generally increased over time, the absolute change in the deprivation gap (i.e. the difference between the five-year survival estimate for the most affluent and the most deprived women) was stable or only slightly smaller for women diagnosed more recently (Lyratzopoulos et al. 2011; Exarchakou et al. 2018; Dalton et al. 2019; Rachet et al. 2010). In other words, over 20 years since these differences in survival were first identified, more deprived women with breast cancer continue to have lower survival and shorter life expectancy than more affluent women with the same disease (Syriopoulou et al. 2017; Rutherford et al. 2015).

Potential explanations for socioeconomic differences in survival can be separated into three main groups: those related to characteristics of the patient and the tumour, to the healthcare system and to the wider social environment.

Patient and Tumour Characteristics

Place of Birth and Age at Diagnosis

Breast cancer is generally more common among more affluent women (Nur et al. 2015). However, more deprived women are generally older at diagnosis: less often aged under 50 years and more often aged 65 years or over (Nur et al. 2015; Walsh et al. 2014).

It has been observed that the deprivation gap in short-term (one-year) breast cancer survival tends to be wider among older women (Nur et al. 2015), but socioeconomic inequalities in survival remain evident up to 10 years after diagnosis in all age groups (Berger et al. 2012; Nur et al. 2015).

A slightly different result has been reported from Sweden, where social gradients in breast cancer survival were of similar magnitude for women aged 20–49 and 50–65 years, and no statistically significant socioeconomic differences in survival were evident among women aged 66–79 years (Eaker et al. 2009).

Lower survival among cancer patients with lower social position may in part be attributed to differences in nationality and/or ethnicity. However, one Swedish study found no significant differences in the risk of dying from breast cancer between native Swedes and immigrant women or their daughters at each level of education (Beiki et al. 2012). Further possible explanations include more advanced stage or higher levels of comorbidity at diagnosis among more deprived women (Dalton et al. 2019), or socioeconomic disparities in participation in screening programmes and in the management of the primary tumour or any recurrence, especially among the elderly (Nur et al. 2015).

Disease Stage at Diagnosis

The stage or extent of disease at diagnosis is a crucial contributory factor to the duration of survival. Notable socioeconomic differences in the distribution of stage at diagnosis have been reported, with more affluent women generally being diagnosed with less advanced tumours (Eaker et al. 2009; Quaglia et al. 2011; Berger et al. 2012; Bower et al. 2019), irrespective of age at diagnosis (Rutherford et al. 2013).

Five-year relative survival estimates at each stage at diagnosis were comparable among the deprivation quintiles 1–4 but were approximately 10% lower in the fifth, or most deprived, quintile (Rutherford et al. 2013). This suggests that a substantial reduction in the number of premature deaths among women with breast cancer could be achieved if inequalities in stage at diagnosis could be eliminated (Rutherford et al. 2013; Bower et al. 2019; Aarts et al. 2013). Although differences in stage at diagnosis explained most of the survival differences between women in deprivation quintiles 3, 4 and 5, eliminating differences in the distribution of stage would only be expected to remove about half of the inequalities in survival between women in the most deprived and most affluent groups (Rutherford et al. 2013; Li et al. 2016).

Cell Proliferation Rate and Molecular Markers

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, many clinical trials and hospital-based studies have shown that breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease, with gene expression patterns or immunohistochemical determination of oestrogen (ER) and progesterone (PgR) receptor expression, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) over-expression, and cell proliferation status identifying distinct subtypes that are also characterised by different outcomes. Differences in cancer survival between these groups have been confirmed at the population level. Women with hormone-positive (ER+ or PgR+), HER2-negative (HER2-) tumours, or tumours with low cell proliferation rate, experience better survival than women diagnosed with hormone-negative (ER- and PgR-), HER2+, or tumours with a high cell proliferation rate (Minicozzi et al. 2013).

Less-educated women seem to be diagnosed more often with tumours that have a high proliferation rate (Eaker et al. 2009) and less often with hormone-positive tumours than women with higher levels of education (Walsh et al. 2014). More deprived women with breast cancer are also less likely to be HER2-negative.

It has also been found that even after adjusting for age, period of diagnosis and stage at diagnosis, the same socioeconomic differences in survival were still present among women with hormone-positive tumours or tumours with a low cell proliferation rate (Eaker et al. 2009).

It has been suggested that the p53 mutation, which may have aberrant responses to inflammatory stress, with therapeutic consequences, may partly account for the worse prognosis in more deprived women (Baker et al. 2010). Among women with the p53 mutation, those in the most deprived group (the tenth decile) were more likely to relapse, or to die, than those in deciles 1–9.

Lifestyle and Comorbidity

Women diagnosed with breast cancer in more deprived groups are more likely to be current smokers or ex-smokers and to have a higher body mass index (BMI) but are less likely to be current drinkers (Morris et al. 2017; Larsen et al. 2015). While some authors have observed that women living in more deprived areas have higher levels of comorbidity when diagnosed with breast cancer (Dialla et al. 2015), such as diabetes (Redaniel et al. 2012), others have not found any association between deprivation and comorbidity (Morris et al. 2017).

However, the deprivation gap in survival for women with breast cancer was present irrespective of obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking habit or comorbidity (Morris et al. 2017). Adjustment for characteristics of the woman, her tumour and any comorbidity had little influence on socioeconomic differences in survival (Morris et al. 2016; Ward et al. 2018), but adjustment for lifestyle, represented by metabolic indicators, smoking and alcohol habits, does reduce the deprivation gap to some extent (Larsen et al. 2015; Redaniel et al. 2012; Walsh et al. 2014).

These findings suggest that improvements in lifestyle might improve survival among women with lower socioeconomic position (Larsen et al. 2015).

Factors Related to the Healthcare System

Screening

Inequalities in the use of breast cancer screening services between socioeconomic groups defined by education level have been described in several European countries (Palencia et al. 2010). These inequalities are more marked in countries that do not have organised cancer screening programmes.

However, adherence to breast cancer screening recommendations is variable. Women living in deprived or rural areas, and those who live far from screening centres, are less compliant with screening recommendations (Ouedraogo et al. 2014), as well as women who are obese or diabetic (Constantinou et al. 2016).

In the Netherlands, in situ tumours (mostly screen-detected) were more commonly seen among more affluent women, suggesting higher attendance at the screening programme (Bastiaannet et al. 2011). By contrast, in one region of England, the proportion of regional and advanced tumours was particularly high in the most deprived women with screen-detected tumours (Morris et al. 2016). These women also had larger tumours than those diagnosed in more affluent women with screen-detected tumours. The authors suggested that deprived women may use screening as an entry point to the healthcare system, after they are already symptomatic, more often than women in more affluent categories.

Studies in London and Ireland (Davies et al. 2013; Walsh et al. 2014) have shown that more deprived women were less likely to have presented via screening. Similar results have been seen in France, where for women diagnosed during 1998–2009, residence in a deprived area was linked to advanced stage at diagnosis only among those aged 50–74 years (Dialla et al. 2015). This suggests socioeconomic disparities in participation in organised breast cancer screening programmes. In England, women in the most deprived group also appeared to wait longer for a hospital appointment after the general practitioner’s referral (Downing et al. 2007) and to experience somewhat longer delays between the last breast-related consultation and diagnosis, although the difference was not significant (Morris et al. 2017).

The deprivation gap in breast cancer survival has been reported by many authors, whether the tumour is screen-detected or not (Morris et al. 2015, 2016; Davies et al. 2013; Woods et al. 2016; Aarts et al. 2011). However, among screen-detected women, the deprivation gap in survival was either similar to (Morris et al. 2015; Woods et al. 2016) or somewhat smaller than (Morris et al. 2016; Aarts et al. 2011; Davies et al. 2013) the deprivation gap in survival among women whose tumour was diagnosed clinically, even after correction for lead-time bias and potential over-diagnosis (Morris et al. 2015).

Two studies in Italy, in Tuscany and Emilia Romagna, have shown that, after adjustment for stage, the risk of death from breast cancer becomes similar across the socioeconomic spectrum 10 years after the introduction of a screening programme for women. These changes were seen among women in the age range invited to screening (50–69 years), but not among women diagnosed under the age of 50 years (Puliti et al. 2012; Pacelli et al. 2014). These studies suggest that the screening programmes successfully reduced socioeconomic inequalities in early detection, shortened the time to diagnosis and improved the quality of treatment in more deprived groups, thus producing greater equity in breast cancer survival.

However, since socioeconomic differences in survival remain evident after participation in a screening programme has been taken into account (Rachet et al. 2010; Feller et al. 2017), they could be related to the lack of timely screening, which could lead to delayed diagnosis and a larger tumour burden at diagnosis (Siddharth and Sharma 2018). Some authors have concluded that the type and quality of treatment provided could also play a role, although a few studies have found no effect of treatment on socioeconomic survival differences (Morris et al. 2016; Li et al. 2016).

Further investigations are required of the timeliness and appropriateness of treatment, adherence to treatment and the quality of clinical follow-up between women with breast cancer in the different social groups, together with the influence of these variables on cancer care.

Treatment and Access to Care

Substantial differences in access to treatment exist both between and within European countries, and they contribute to differences in cancer survival (Siddharth and Sharma 2018).

For example, in England, the most deprived women appeared to have to wait a longer time from diagnosis to surgery than the most affluent women (Downing et al. 2007; Morris et al. 2016, 2017), although those findings were not confirmed after selecting women with localised stage disease who only underwent surgical treatment (Redaniel et al. 2013). Furthermore, women receiving some or all of their care within private provider(s) were often living in the most affluent area, as well as being younger, non-screen detected and less often diagnosed at an early stage, than women who were treated in public hospitals (Davies et al. 2016).

One Italian study found that women with a very low socioeconomic status who were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer during 1996–2000 in Liguria were less likely to be treated with curative intent or according to current guidelines (Quaglia et al. 2011). In particular, more deprived women in the Northern and Yorkshire region of England who were diagnosed during 1998–2000 were less likely to receive surgery, and when they did receive it, were less likely to have breast-conserving surgery (Downing et al. 2007), or to receive radiotherapy or chemotherapy, according to a Swedish study of women who were diagnosed during 1993–2003 in the Uppsala/Örebro region (Eaker et al. 2009).

By contrast, another Italian study found that socioeconomic indicators (education, occupational status and housing characteristics) showed only a marginal independent effect on indicators of the pathway of care relative to timeliness, for 50- to 69-year-old women diagnosed in Piedmont during 1995–2008 (Zengarini et al. 2016).

After taking into account age and stage at diagnosis, the association between socioeconomic status and survival was stronger among women who underwent breast-conserving surgery as part of treatment with curative intent than those who underwent mastectomy (Downing et al. 2007). It is striking that socioeconomic differences in survival have been shown to persist even after a wide range of factors have been taken into account, including the waiting time from diagnosis to surgery (Redaniel et al. 2013), chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormonal treatment (Eaker et al. 2009; Jack et al. 2009; Davies et al. 2010; Bastiaannet et al. 2011), place of treatment (private vs. public hospital) (Davies et al. 2016), and health service region (Skyrud et al. 2016), although these adjustments do all contribute to reducing socioeconomic inequalities (Jack et al. 2009; Eaker et al. 2009; Quaglia et al. 2011; Davies et al. 2016; Aarts et al. 2011). However, they seem to disappear after considering the diagnostic interval, that is, the time from primary care presentation to definitive diagnosis (Redaniel et al. 2015), thus suggesting that differences in access to medical services do play a role. Examples include the availability of clinical facilities (e.g. computed tomography scanners), the organisation of the healthcare system (e.g. percentage of the labour force working in health services) and factors describing the sociodemographic environment where the patient lives (e.g. total public expenditure), all of which are associated with survival (Lillini et al. 2011), as well as differences in access to specialist centres, especially given that women often have to travel long distances (Dialla et al. 2015; Gentil et al. 2012), ease of travel to appointments, flexibility of work, other commitments and the level of social support (Morris et al. 2016).

Factors Related to the Social Environment

Familial Environment

According to one study using data from the Irish National Cancer Registry (Walsh et al. 2014), no more than half of the socioeconomic gap in breast cancer survival can be explained by the available information on patients and tumour characteristics, and treatment, that is, age, stage, comorbidities at diagnosis, hormonal status and all treatments administered. This suggests that other factors or mechanisms may be involved.

When women are diagnosed with breast cancer, it can affect the emotional, physical, psychological and social well-being of their families, as well as the women themselves (Gluck and Mamounas 2010). This may be reflected in lifestyle changes during treatment or reduction of household income (e.g. through the personal costs of receiving treatment, or restriction of the woman’s ability to work).

Breast cancer impacts society both directly (e.g. through health system costs: expenses associated with treatment) and indirectly (e.g. through the loss of labour productivity). All these aspects may contribute to socioeconomic differences in survival among women with breast cancer. However, cultural factors within the family may also play a role.

It has been noted that the presence of a positive family history of breast cancer eliminated socioeconomic differences in access to screening and optimal treatment, but this did not translate into a reduction in socioeconomic differences in breast cancer survival (Verkooijen et al. 2009). In fact, among more deprived women, the presence of a family history increased the probability of being detected at an earlier stage compared with deprived women who did not have a family history. However, most deprived women were those with the lowest positive effect of having a family history on the risk of death from their breast cancer. The authors argued that a possible explanation includes socioeconomic differences in lifestyle, as mentioned above. Thus, the positive effect of improved access to screening and optimal treatment associated with a positive family history may be offset by the higher prevalence of unfavourable lifestyles among the most deprived women.

It has also been found that lower education level among adult children of mothers with a breast cancer diagnosis is associated with poorer survival, independently of the mother’s education level or income (Brooke et al. 2017). This association was stronger among women diagnosed at an earlier clinical stage. These results suggest that health awareness or the ability to interpret information, rather than material resources, may be particularly important in improving outcome.

Social Relationships

Favourable associations have also been observed between positive developments in romantic relationships and hobbies and death from breast cancer. Similarly, higher breast cancer mortality has been reported in relation to negative life events, even after adjusting for characteristics of the patient and the tumour, lifestyle and socioeconomic status (Heikkinen et al. 2017). It would seem that social interaction with and support from friends and family are particularly important in times of illness, and they may contribute to disparities in cancer outcomes.

Comment

The relation between breast cancer survival and the characteristics of the woman and her tumour, including biological, lifestyle, social and health-seeking factors, is complex (Fig. 7.3). Thus, differences in women’s baseline characteristics, primary care consultation patterns, symptom presentation, and the time intervals between the first report of symptoms and the eventual diagnosis, and then between diagnosis and the start of treatment, all contribute to socioeconomic differences in breast cancer survival. Factors related to the behavioural norms or education of the woman’s children (Torssander 2014) or causes of death other than breast cancer (Rutherford et al. 2015) are plausibly correlated with these differences.

Potential links between deprivation and breast cancer survival and the woman’s biological, lifestyle and health-seeking characteristics. SD screen-detected, non-SD non-screen-detected. (Reprinted from Morris et al. (2017), Fig. 1, licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/])

It is insufficient to concentrate attention on one small area within a complex whole. Rudolf Virchow (1848), the founder of cellular pathology, pointed out a long time ago: Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale. “Medicine, as a social science, as the science of human beings, has the obligation to point out problems and to attempt their theoretical solution: the politician, the practical anthropologist, must find the means for their actual solution” (Munro 2014). Thus, the ultimate goal of research is not only to improve our understanding of a problem but also to show how research findings can be translated into clinical benefits, in particular into interventions that deliver benefits to more socioeconomically deprived patients through earlier diagnosis and better treatment, follow-up and rehabilitation, in order to improve cancer outcomes overall, as well as to reduce the socioeconomic gap in survival (Dalton et al. 2019).

Virtually all the studies we have reviewed suggest that socioeconomic inequalities in breast cancer survival remain even after controlling for stage at diagnosis, treatment, hormonal receptors, the woman’s lifestyle, comorbidities at diagnosis and screening attendance. Deeper insight into the complex inter-relation between these factors and breast cancer survival is required. Studies must include all these factors, together with the social environment, as well as socioeconomic status. Studies of this type could contribute to a better understanding of socioeconomic inequalities in breast cancer survival, and they would be expected to offer more useful information for public health interventions.

Recommendations

Demographic factors, socioeconomic conditions and clinical aspects should be considered together in research, policy and clinical or public health interventions aimed at reducing socioeconomic inequalities in breast cancer survival.

Clinicians should address the broader environment and social context of patient care, at the same time as integrating the increasing molecular understanding of cancer. They also need to be aware of the educational context of their patients with breast cancer and to pay particular attention to women who require extra support. Further improvements are needed in the quality of care in healthcare facilities that are not reference or tertiary centres, and to the distribution of these specialised centres in European countries, to avoid aggravating socioeconomic differences in outcome. Screening programmes should be more closely adapted to the personal and social characteristics of the women they serve. Better research will be required to pinpoint the causes that underlie socioeconomic differences in survival, especially in those European countries where this important issue has never been considered.

References

Aapro M, Astier A, Audisio R, Banks I, Bedossa P, Brain E, Cameron D, Casali P, Chiti A, De Mattos-Arruda L, Kelly D, Lacombe D, Nilsson PJ, Piccart M, Poortmans P, Riklund K, Saeter G, Schrappe M, Soffietti R, Travado L, van Poppel H, Wait S, Naredi P. Identifying critical steps towards improved access to innovation in cancer care: a European CanCer Organisation position paper. Eur J Cancer. 2017;82:193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.04.014.

Aarts MJ, Voogd AC, Duijm LE, Coebergh JW, Louwman WJ. Socioeconomic inequalities in attending the mass screening for breast cancer in the south of the Netherlands--associations with stage at diagnosis and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128(2):517–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-011-1363-z.

Aarts MJ, Kamphuis CB, Louwman MJ, Coebergh JW, Mackenbach JP, van Lenthe FJ. Educational inequalities in cancer survival: a role for comorbidities and health behaviours? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(4):365–73. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2012-201404.

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, Niksic M, Bonaventure A, Valkov M, Johnson CJ, Esteve J, Ogunbiyi OJ, Azevedo ESG, Chen WQ, Eser S, Engholm G, Stiller CA, Monnereau A, Woods RR, Visser O, Lim GH, Aitken J, Weir HK, Coleman MP, Group CW. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1023–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33326-3.

Baker L, Quinlan PR, Patten N, Ashfield A, Birse-Stewart-Bell LJ, McCowan C, Bourdon JC, Purdie CA, Jordan LB, Dewar JA, Wu L, Thompson AM. p53 mutation, deprivation and poor prognosis in primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(4):719–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605540.

Bastiaannet E, de Craen AJ, Kuppen PJ, Aarts MJ, van der Geest LG, van de Velde CJ, Westendorp RG, Liefers GJ. Socioeconomic differences in survival among breast cancer patients in the Netherlands not explained by tumor size. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127(3):721–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-010-1250-z.

Beiki O, Hall P, Ekbom A, Moradi T. Breast cancer incidence and case fatality among 4.7 million women in relation to social and ethnic background: a population-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(1):R5. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr3086.

Belot A, Remontet L, Rachet B, Dejardin O, Charvat H, Bara S, Guizard AV, Roche L, Launoy G, Bossard N. Describing the association between socioeconomic inequalities and cancer survival: methodological guidelines and illustration with population-based data. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:561–73. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S150848.

Berger F, Doussau A, Gautier C, Gros F, Asselain B, Reyal F. Impact of socioeconomic status on stage at diagnosis of breast cancer. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2012;60(1):19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respe.2011.08.066.

Bower H, Andersson TM, Syriopoulou E, Rutherford MJ, Lambe M, Ahlgren J, Dickman PW, Lambert PC. Potential gain in life years for Swedish women with breast cancer if stage and survival differences between education groups could be eliminated - three what-if scenarios. Breast. 2019;45:75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2019.03.005.

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492.

Brooke HL, Ringback Weitoft G, Talback M, Feychting M, Ljung R. Adult children’s socioeconomic resources and mothers’ survival after a breast cancer diagnosis: a Swedish population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e014968. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014968.

Constantinou P, Dray-Spira R, Menvielle G. Cervical and breast cancer screening participation for women with chronic conditions in France: results from a national health survey. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:255. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2295-0.

Dalton SO, Olsen MH, Johansen C, Olsen JH, Andersen KK. Socioeconomic inequality in cancer survival - changes over time. A population-based study, Denmark, 1987–2013. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):737–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2019.1566772.

Davies EA, Linklater KM, Coupland VH, Renshaw C, Toy J, Park R, Petit J, Housden C, Moller H. Investigation of low 5-year relative survival for breast cancer in a London cancer network. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(7):1076–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605857.

Davies EA, Renshaw C, Dixon S, Moller H, Coupland VH. Socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in screen-detected breast cancer in London. J Public Health (Oxf). 2013;35(4):607–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdt002.

Davies EA, Coupland VH, Dixon S, Mokbel K, Jack RH. Comparing the case mix and survival of women receiving breast cancer care from one private provider with other London women with breast cancer: pilot data exchange and analyses. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:421. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2439-2.

Dialla PO, Arveux P, Ouedraogo S, Pornet C, Bertaut A, Roignot P, Janoray P, Poillot ML, Quipourt V, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS. Age-related socio-economic and geographic disparities in breast cancer stage at diagnosis: a population-based study. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(6):966–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv049.

Downing A, Prakash K, Gilthorpe MS, Mikeljevic JS, Forman D. Socioeconomic background in relation to stage at diagnosis, treatment and survival in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(5):836–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603622.

Eaker S, Halmin M, Bellocco R, Bergkvist L, Ahlgren J, Holmberg L, Lambe M, Uppsala/Orebro Breast Cancer G. Social differences in breast cancer survival in relation to patient management within a National Health Care System (Sweden). Int J Cancer. 2009;124(1):180–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.23875.

Exarchakou A, Rachet B, Belot A, Maringe C, Coleman MP. Impact of national cancer policies on cancer survival trends and socioeconomic inequalities in England, 1996–2013: population based study. BMJ. 2018;360:k764. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k764.

Feller A, Schmidlin K, Bordoni A, Bouchardy C, Bulliard JL, Camey B, Konzelmann I, Maspoli M, Wanner M, Clough-Gorr KM, SNC and the NICER working Group. Socioeconomic and demographic disparities in breast cancer stage at presentation and survival: a Swiss population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(8):1529–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30856.

Gentil J, Dabakuyo TS, Ouedraogo S, Poillot ML, Dejardin O, Arveux P. For patients with breast cancer, geographic and social disparities are independent determinants of access to specialized surgeons. A eleven-year population-based multilevel analysis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:351. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-351.

Gluck S, Mamounas T. Improving outcomes in early-stage breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 2010;24(11 Suppl 4):1–15.

Heikkinen S, Miettinen J, Pukkala E, Koskenvuo M, Malila N, Pitkaniemi J. Impact of major life events on breast-cancer-specific mortality: a case fatality study on 8000 breast cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;48:62–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2017.03.008.

Jack RH, Davies EA, Moller H. Breast cancer incidence, stage, treatment and survival in ethnic groups in South East England. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(3):545–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604852.

Kogevinas M, Porta M. Socioeconomic differences in cancer survival: a review of the evidence. IARC Sci Publ. 1997;(138):177–206. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/13875194_Kogevinas_M_Porta_MSocioeconomic_differences_in_cancer_survival_a_review_of_the_evidence_IARC_Sci_Publ_138_177–206.

Larsen SB, Kroman N, Ibfelt EH, Christensen J, Tjonneland A, Dalton SO. Influence of metabolic indicators, smoking, alcohol and socioeconomic position on mortality after breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):780–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2014.998774.

Li R, Daniel R, Rachet B. How much do tumor stage and treatment explain socioeconomic inequalities in breast cancer survival? Applying causal mediation analysis to population-based data. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(6):603–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0155-5.

Lillini R, Vercelli M, Quaglia A, Micheli A, Capocaccia R. Use of socio-economic factors and healthcare resources to estimate cancer survival in European countries with partial national cancer registration. Tumori. 2011;97(3):265–74. https://doi.org/10.1700/912.10020.

Lyratzopoulos G, Barbiere JM, Rachet B, Baum M, Thompson MR, Coleman MP. Changes over time in socioeconomic inequalities in breast and rectal cancer survival in England and Wales during a 32-year period (1973–2004): the potential role of health care. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(7):1661–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq647.

Minicozzi P, Bella F, Toss A, Giacomin A, Fusco M, Zarcone M, Tumino R, Falcini F, Cesaraccio R, Candela G, La Rosa F, Federico M, Sant M. Relative and disease-free survival for breast cancer in relation to subtype: a population-based study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139(9):1569–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-013-1478-1.

Morris M, Woods LM, Rogers N, O’Sullivan E, Kearins O, Rachet B. Ethnicity, deprivation and screening: survival from breast cancer among screening-eligible women in the West Midlands diagnosed from 1989 to 2011. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(3):548–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.204.

Morris M, Woods LM, Rachet B. What might explain deprivation-specific differences in the excess hazard of breast cancer death amongst screen-detected women? Analysis of patients diagnosed in the West Midlands region of England from 1989 to 2011. Oncotarget. 2016;7(31):49939–47. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.10255.

Morris M, Woods LM, Bhaskaran K, Rachet B. Do pre-diagnosis primary care consultation patterns explain deprivation-specific differences in net survival among women with breast cancer? An examination of individually-linked data from the UK West Midlands cancer registry, national screening programme and Clinical Practice Research Datalink. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3129-4.

Munro AJ. Comparative cancer survival in European countries. Br Med Bull. 2014;110(1):5–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldu009.

Nur U, Lyratzopoulos G, Rachet B, Coleman MP. The impact of age at diagnosis on socioeconomic inequalities in adult cancer survival in England. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(4):641–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2015.05.006.

Ouedraogo S, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS, Roussot A, Pornet C, Sarlin N, Lunaud P, Desmidt P, Quantin C, Chauvin F, Dancourt V, Arveux P. European transnational ecological deprivation index and participation in population-based breast cancer screening programmes in France. Prev Med. 2014;63:103–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.12.007.

Pacelli B, Carretta E, Spadea T, Caranci N, Di Felice E, Stivanello E, Cavuto S, Cisbani L, Candela S, De Palma R, Fantini MP. Does breast cancer screening level health inequalities out? A population-based study in an Italian region. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(2):280–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt119.

Palencia L, Espelt A, Rodriguez-Sanz M, Puigpinos R, Pons-Vigues M, Pasarin MI, Spadea T, Kunst AE, Borrell C. Socio-economic inequalities in breast and cervical cancer screening practices in Europe: influence of the type of screening program. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(3):757–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq003.

Puliti D, Miccinesi G, Manneschi G, Buzzoni C, Crocetti E, Paci E, Zappa M. Does an organised screening programme reduce the inequalities in breast cancer survival? Ann Oncol. 2012;23(2):319–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr121.

Quaglia A, Lillini R, Casella C, Giachero G, Izzotti A, Vercelli M, Liguria Region Tumour R. The combined effect of age and socio-economic status on breast cancer survival. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77(3):210–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.02.007.

Rachet B, Ellis L, Maringe C, Chu T, Nur U, Quaresma M, Shah A, Walters S, Woods L, Forman D, Coleman MP. Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival in England after the NHS cancer plan. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(4):446–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605752.

Redaniel MT, Jeffreys M, May MT, Ben-Shlomo Y, Martin RM. Associations of type 2 diabetes and diabetes treatment with breast cancer risk and mortality: a population-based cohort study among British women. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(11):1785–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-0057-0.

Redaniel MT, Martin RM, Cawthorn S, Wade J, Jeffreys M. The association of waiting times from diagnosis to surgery with survival in women with localised breast cancer in England. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(1):42–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.317.

Redaniel MT, Martin RM, Ridd MJ, Wade J, Jeffreys M. Diagnostic intervals and its association with breast, prostate, lung and colorectal cancer survival in England: historical cohort study using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126608.

Rutherford MJ, Hinchliffe SR, Abel GA, Lyratzopoulos G, Lambert PC, Greenberg DC. How much of the deprivation gap in cancer survival can be explained by variation in stage at diagnosis: an example from breast cancer in the East of England. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(9):2192–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28221.

Rutherford MJ, Andersson TM, Moller H, Lambert PC. Understanding the impact of socioeconomic differences in breast cancer survival in England and Wales: avoidable deaths and potential gain in expectation of life. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(1):118–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2014.11.002.

Sant M, Minicozzi P, Primic-Zakelj M, Otter R, Francisci S, Gatta G, Berrino F, De Angelis R. Cancer survival in Europe, 1999–2007: doing better, feeling worse? Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(15):2101–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.019.

Siddharth S, Sharma D. Racial disparity and triple-negative breast cancer in African-American women: a multifaceted affair between obesity, biology, and socioeconomic determinants. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers10120514.

Skyrud KD, Bray F, Eriksen MT, Nilssen Y, Moller B. Regional variations in cancer survival: impact of tumour stage, socioeconomic status, comorbidity and type of treatment in Norway. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(9):2190–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29967.

Syriopoulou E, Bower H, Andersson TM, Lambert PC, Rutherford MJ. Estimating the impact of a cancer diagnosis on life expectancy by socio-economic group for a range of cancer types in England. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(9):1419–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.300.

Torssander J. Adult children’s socioeconomic positions and their parents’ mortality: a comparison of education, occupational class, and income. Soc Sci Med. 2014;122:148–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.043.

Verkooijen HM, Rapiti E, Fioretta G, Vinh-Hung V, Keller J, Benhamou S, Vlastos G, Chappuis PO, Bouchardy C. Impact of a positive family history on diagnosis, management, and survival of breast cancer: different effects across socio-economic groups. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(9):1689–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-009-9420-1.

Virchow R. Die Medicin ist eine sociale Wissenschaft. Berlin: Die Medizinische Reform; 1848.

Walsh PM, Byrne J, Kelly M, McDevitt J, Comber H. Socioeconomic disparity in survival after breast cancer in Ireland: observational study. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111729. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111729.

Ward SE, Richards PD, Morgan JL, Holmes GR, Broggio JW, Collins K, Reed MWR, Wyld L. Omission of surgery in older women with early breast cancer has an adverse impact on breast cancer-specific survival. Br J Surg. 2018;105(11):1454–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10885.

Woods LM, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Origins of socio-economic inequalities in cancer survival: a review. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(1):5–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdj007.

Woods LM, Rachet B, O’Connell D, Lawrence G, Coleman MP. Impact of deprivation on breast cancer survival among women eligible for mammographic screening in the West Midlands (UK) and New South Wales (Australia): women diagnosed 1997–2006. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(10):2396–403. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29983.

Zengarini N, Ponti A, Tomatis M, Casella D, Giordano L, Mano MP, Segnan N, Whitehead M, Costa G, Spadea T. Absence of socioeconomic inequalities in access to good-quality breast cancer treatment within a population-wide screening programme in Turin (Italy). Eur J Cancer Prev. 2016;25(6):538–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000211.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Minicozzi, P., Coleman, M.P., Allemani, C. (2021). Social Disparities in Survival from Breast Cancer in Europe. In: Launoy, G., Zadnik, V., Coleman, M.P. (eds) Social Environment and Cancer in Europe. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69329-9_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69329-9_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-69328-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-69329-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)