Abstract

In Peninsular Malaysia, the indigenous people (Orang Asli) depend on the forest for subsistence. Hunting wildlife and collecting forest products are part of their cultural practices and lifestyle. However, little is known about how the Orang Asli hunt wildlife. As such, it is important to monitor the wildlife hunting patterns of the Orang Asli to safeguard natural resources and help in animal conservation. Using both qualitative and quantitative methods, we investigated how wildlife is perceived by the Orang Asli and the traditional hunting practices of the Semoq Beri sub-tribe at a forest reserve in the state of Terengganu, Malaysia. We found that 53 wildlife species are hunted by the Orang Asli for various purposes. They tracked the animals by their footprints and used snares, traps and blowpipes to capture them. It was also noted that they do not hunt big animals, but the lucrative wildlife market has encouraged them to hunt small protected animals for better income. The findings of this study may be important to help sustain the natural resources in the forest for the Orang Asli.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

In Peninsular Malaysia, the indigenous people are a minority known as the Orang Asli. They are made up of three major tribes (Negrito, Senoi and Proto-Malay) divided into 18 sub-tribes (Carey 1976), and their history may be traced back to at least 25,000 years (Nicholas 2000). The Orang Asli have been called the “first people” or “original people” of Malaysia. Across the peninsula, all sub-tribes partake in similar activities in their daily lives, which include hunting, foraging and gathering forest resources (Rambo 1979).

Being primarily forest-dependent people, the Orang Asli are nomadic and semi-nomadic, acquiring various resources in and around tropical forests (Kuchikura 1986). Their high dependency on forest resources and products has been widely studied, particularly among the Semoq Beri and Batek communities (Ramle et al. 2014a; Tuck-Po 1998). Historically being land-security dependent and unaccustomed to cash economies, coupled with the lack of education and intermediate technology, these are likely reasons for their high dependence on forest resources for generations. Failure to fully assimilate into contemporary economic systems has resulted in them being plagued by perennial poverty. Recently, based on the report by the United Nations Development Programme, around 34% of the Orang Asli households lived in poverty (Balakrishnan 2016). Previous studies on forest resource utilisation by the Orang Asli have been conducted in the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia involving the Jah Hut, Semelai, Lanoh, Temiar, Temuan and Semang sub-tribes (Yahaya 2015; Milow et al. 2013; Azliza et al. 2012; Ong et al. 2012a, b; Howell et al. 2010; Samuel et al. 2010). However, hardly any study has documented Orang Asli communities living in the east coast. The sub-tribes mainly found in east coast states of Pahang, Kelantan and Terengganu are the Semoq Beri and Batek.

Based on what we know on the resources used by the Orang Asli, they harvested a variety of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) from terrestrial and aquatic sources (Arnold and Ruiz 1996). According to Burkill (1935), the Malayan rainforest contained more than 1700 species of plants and animals that have more than 5000 uses. Examples of NTFPs harvested in Peninsular Malaysia include agarwood, rattan, honey, bamboo, fruits and a variety of herbs, besides bushmeat like deer, porcupine and wild boar. Apart from using NTFPs for medicinal purposes, the Orang Asli also heavily relied on them for subsistence and materials for building their houses. In recent times, the Orang Asli have begun to harvest NTFPs in exchange for cash to purchase daily necessities. For instance, Jah Hut communities derived income from selling NTFPs, such as bamboo, fruits, vegetables, rattan and agarwood (Howell et al. 2010). In addition, NTFPs are increasingly being used by the Orang Asli as ornaments, like chenille plants (Acalypha hispida) and ferns (Asparagus africanus) (Milow et al. 2013).

The Orang Asli use a number of plant species for medicinal purposes. Recent ethnobotanical studies in Peninsular Malaysia indicated that the Orang Asli utilised more than 200 plants to treat illnesses, such as hypertension, diabetes, stomachache, diarrhoea and fever (Azliza et al. 2012; Ong et al. 2012a, b; Samuel et al. 2010; Howell et al. 2010). The most common plants include petai (Parkia speciosa), tongkat ali (Eurycoma longifolia ) and agarwood (Aquilaria malaccensis). The Orang Asli also use animals for a variety of purposes. However, only a few studies have documented the use of animals by the Orang Asli. At least 12 species of animals have been utilised for medicinal purposes (Yahaya 2015; Azliza et al. 2012; Howell et al. 2010). In Sarawak, however, up to 52 species of animals are utilised by the indigenous people for medicinal purposes (Azlan and Faisal 2006). Species regarded to have medicinal value by the indigenous people of Malaysia, including the peninsular Orang Asli, are the reticulated python (Python reticulatus ), Malayan porcupine (Hystrix brachyura) and black giant squirrel (Ratufa bicolor). At least 10 terrestrial and aquatic animal taxa are consumed by the Orang Asli of the peninsula: the river terrapin (Batagur baska), tortoise (Testudo spp.), monitor lizards (Varanus spp.), Malayan porcupine (Hystrix brachyura), Sunda pangolin (Manis javanica ), wild pig (Sus scrofa) , macaques (Macaca spp.) , barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak) , plaintain squirrel (Callosciurus notatus) and mousedeers (Tragulus spp.). In some Orang Asli communities, animals are commercially traded or kept as pets (Yahaya 2015; Howell et al. 2010). Unfortunately, some animal species utilised by the Orang Asli (e.g. the Sunda pangolin) are considered critically endangered in the IUCN Red List (IUCN 2016) and are totally protected under the Malaysian Wildlife Conservation Act (2010).

Traditionally, the Orang Asli communities are known to exploit natural resources to sustain their livelihood. Today, many of the communities have been resettled in villages outside forests. Under the Sixth Schedule of the Wildlife Conservation Act (2010), the Orang Asli are permitted to hunt 10 species of wildlife for their own consumption. Nevertheless, there is a lack of information on the present state of wildlife being hunted by the Orang Asli and their hunting practices.

The Semoq Beri was chosen in this study because previous studies of this sub-tribe have only explored their concept of the forest and traditional knowledge (Ramle et al. 2014a, b), but did not look into their hunting practices. This has important implications for the conservation of threatened wildlife species. Therefore, by using qualitative and quantitative methods, we aim to: (1) determine the animals hunted by the Semoq Beri people living in the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, (2) elucidate their hunting practices and (3) identify the favourite mammals hunted by this sub-tribe.

Methods

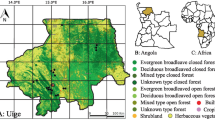

In a period of 6 months (between August 2015 to January 2016), information was gathered on the wildlife perceived and hunted by the Orang Asli in Kampung Sungai Berua (5° 4′ 49.8″ N 102° 53′ 2.76″ E) in Kenyir, Terengganu (Fig. 1). The majority of the Orang Asli people in the village belonged to the Semoq Beri sub-tribe. Ethic approval was obtained from the Orang Asli Development Department (JAKOA) of the Rural Development Ministry, and consent was requested from the village head. Qualitative approach using face-to-face interviews was conducted on key informants comprising traditional medicine practitioners and hunters. Wildlife observed during the survey was photographed for in-situ identification purposes according to Francis (2008) for mammals, Robson (2000) for birds and Indraneil (2010) for reptiles. A series of questionnaires were employed to determine the wildlife hunted by the Semoq Beri folk.

Relatively abundant data on mammals in Kenyir Forest Reserve (Fig. 1) was collected from April to November (eight months). In order to obtain mammal detection/non-detection data, 78 camera traps were fixed on metal poles (in the absence of trees) that were cemented to the ground. Camera traps were installed close to underpass columns to prevent mammals from passing behind the camera. The surrounding vegetation was cleared to provide optimal fields of detection for each camera trap. Camera traps were checked to retrieve data and replace the batteries every two months. The relative abundance of mammal species was defined using the Photographic Capture Rate Index (PCRI). The estimates were averaged across all camera placements within each study area to produce respective mean PCRIs. Independent photos were defined as photos being captured 30 minutes apart from a previous photo with the next at the same location.

Results

Our findings identified 53 animal species utilised by the Semoq Beri Orang Asli as shown in Table 1. The animals comprised 10 species of reptiles, nine birds and 34 mammals. All reptiles and birds had been hunted by the Semoq Beri in the last 12 months. However, for mammals, 14 species including the sun bear, Malayan tiger, Asian elephant and tapir were not hunted. This was because the natives only utilised animals that provided significantly for their livelihood. Among all the identified wildlife game, four species were critically endangered: the river terrapin (Batagur affinis) , red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta ), helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) and Sunda pangolin (Manis javanica). Additionally, there were seven endangered species, 12 vulnerable species and six near threatened species (Table 1).

Camera traps captured a relative abundance of 10 large mammals using the viaducts over 6 months (Table 2). The relative abundance, a PCRI for all large mammals, were defined as the number of independent photos (detections) captured. These estimates were averaged across all camera placements within each study area to produce respective mean PCRIs. Many of the large mammals observed were herbivores and omnivores. Carnivores were relatively rare.

Discussion

In Southeast Asia, indigenous communities had been hunting wildlife mainly for subsistence for at least 40,000 years (Zuraina 1982). In Peninsular Malaysia, the Orang Asli were known to hunt and utilise various species, including endangered ones. Wildlife hunting was considered an important subsistence activity for Orang Asli communities. Regarded as forest people, the Orang Asli could hunt animals easily using traditional knowledge and methods.

Among all the species, 53% were used for household consumption while 40% were utilised for trading and 26% were kept as pets. Besides that, the Orang Asli still relied on animals for medicinal purposes (8%). The parts of a few species were used for traditional treatment, such as pangolin scales and meat, the hornbill’s casque and porcupine bezoars (onion-shaped masses of undigested plant material in the animal’s gut). This finding was supported by a previous study conducted on a similar sub-tribe (Bartholomew et al. 2016).

For data validation, information on actual wildlife had been documented based on secondary data. Table 2 shows the taxonomic list of mammals recorded in the Kenyir forest area. Besides that, data of animals present in Kenyir forest area were also obtained from previous studies (Yong 2015; Clements 2013; Hedges et al. 2013). There were around 44 species of mammals, one of which was critically endangered, six endangered, nine vulnerable and six near threatened under the IUCN Red List (2016). The animals were also categorised as totally protected (64%) or protected (36%) under the Malaysian Wildlife Conservation Act (2010).

The respondents reported hunting at least 11 of the 42 mammals sighted in the forest reserve (26%). According to the interviews, the Semoq Beri basically caught the animals using snares (89%) and blowpipes (73%). For instance, bigger animals such as wild boars, sambar deers and barking deers were hunted using blowpipes, but sometimes, they were also caught in snares. For birds, the Orang Asli mainly used traps to hunt them. Most of the birds were eaten while a few species, such as the blue-rumped parrot (Psittinus cyanurus) and common hill myna (Gracula religiosa) , were kept as pets because of their aesthetic features. Other species, such as turtles and tortoises, were captured using bare hands. These species are used for food, trading and, in some cases, for traditional medicine (e.g. red-eared slider). According to some interview respondents, the Orang Asli communities hunted wildlife based on traits of the particular animals. For instance, they will go out and hunt nocturnal animals at night. They preferred to hunt during the rainy season because it was easier to track the animals’ footprints on the wet ground.

The hunting practices of the Orang Asli was highly related to their culture and belief. For instance, the certain communities did not hunt snakes because of cultural restrictions or taboos that prohibited its consumption (Endicott 2010). With a large number of the Orang Asli adopting Islam as their religion, they had also forgone the consumption of wild pigs or animals that were not considered halal. But although the Orang Asli communities in Kampung Sungai Berua had converted to Islam, some of them still hunted wild boars to sell for subsistence.

The Orang Asli practices were strongly related to their belief in spirits that guided their lives, and those practices could actually allow them to hunt wildlife in a sustainable manner. For instance, the Semoq Beri communities strongly believed in their Semoq Hala (Ramle et al. 2014a), which were spirits that they obeyed. In relation to that, their concept of the forest and its significance, particularly to the Semoq Beri in Terengganu, had been documented (Ramle et al. 2014b). The Semoq Beri community considered themselves responsible for safeguarding the forests around them. They believed that supernatural beings dwelled in the forests and they were responsible for providing and protecting all its resources. As such, the Orang Asli traditionally believed that forest resources must be extracted with a purpose (Hood 1995). The forest was considered as their “bank”, where they could withdraw its wealth when needed, and in a sustainable manner to avoid wastage. The resources must be carefully managed so that the next generation would also be able to make use of the wealth (Ramle et al. 2014b). Several taboos in forest resource harvesting were adhered to by the Orang Asli. For instance, permission or consent must be requested from supernatural beings prior to exploiting any plant or animal for their subsistence. They believed that failure to do so would incur the wrath of the forest spirits, which would lead to punitive consequences befalling their community, such as disease and natural disasters. Wildlife was an important forest resource that contributed to the well-being of the Orang Asli. In this study, we documented that the Orang Asli had utilised wildlife for both consumptive (74%) and non-consumptive (26%) purposes. Similarly in Sabah and Sarawak, the hunting of wildlife by the natives there was also observed to be largely for household food consumption (Azlan and Faisal 2006). This indicated that wildlife played an important role in sustaining the Orang Asli life.

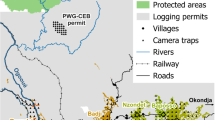

Nevertheless, deforestation, complicated by poaching and lack of legal and positive economic incentives, were main threats to the livelihood of the people that relied on forest resources, including the Orang Asli (Milner-Gulland 2012). The Orang Asli’s livelihood was very vulnerable to developments that encroached on the forests where they used to hunt and earn their living. Based on interviews, the Semoq Beri respondents claimed that animals were increasingly hard to hunt and that they had to spend more time and go deeper into the forest. This could be attributed to the decline in animal populations caused by the loss of habitat due to the high rate of deforestation in nearby Orang Asli settlements. Historically, Orang Asli populations occupying vast acreages of forest had a negligible impact on wildlife. Permanent settlements with limited forests, coupled with the lack of sustainable economic opportunities, had changed the lifestyle of the Orang Asli for the worse and increased their burden. Additionally, poaching by locals and foreigners had been reported in the forests of Peninsular Malaysia (Loh 2016). The threat of paoching had become severe when the Wildlife and National Parks Department (PERHILITAN) reported large hauls of wildlife parts being seized from foreign poachers between 2010 and 2015, all of which had been obtained from protected areas in Terengganu (Fig. 2).

The Orang Asli did not hunt big game animals such as the Asian elephant, but there were cases where locals and foreigners had been detained for killing the elephants (Dasgupta 2017). In Tasik Pedu, Kedah, an elephant carcass was found two weeks after it was belived to have been killed by poachers for its tusks (Anon 2016). In Borneo, two rare elephants were also killed for their tusks (Anon 2017). Meanwhile, the critically endangered Malayan tiger was reportedly in grave danger due to illegal hunting for its meat and body parts (Rosli 2016; Zarina 2016). The Orang Asli were hardly involved in poaching cases. However, there were incidents where they had been used as guides and paid to hunt smaller protected animals (Anon 2011; Yeng 2010). As noted, one of the main reasons that drove the Orang Asli to get involved in poaching was the good money paid by buyers, which could alleviate the burden of supporting their families (Azrina et al. 2011). Several studies had found a positive relationship between illegal harvesting of natural resources and poverty (Mainka and Trivedi 2002). For instance, in Palawan province in the Philippines, poverty was cited as a likely reason for hunting endangered species to sell at high prices among the rural communities there (Shively 1997).

To our knowledge, continuous hunting of protected wildlife might undermine viable populations and the overall survival of targeted species. As wildlife is one of the important components of the tropical forest ecosystem, it would be crucial to conserve and safeguard Malaysia’s heritage for the future generation. Much progress had been made, with laws strictly enforced to prevent the extinction of animals. In Peninsular Malaysia, wildlife was protected under the Wildlife Conservation Act (2010), while Sabah and Sarawak had their own Wildlife Conservation Enactment (1997) and Wild Life Protection Ordinance (1998), respectively.

On the Orang Asli’s right to hunt protected wildlife, the law forbade them from trading or selling animals or parts listed in the Sixth Schedule. Nevertheless, our study documented the hunting of pangolins by the orang Asli. Previous studies had addressed the involvement of the Orang Asli in poaching and trading of several species of animals, including the pangolin (Azrina et al. 2011). Historically, contact between the Orang Asli and outsiders had been established in the fifteenth century through economic activities (Gianno and Bayr 2009). Basically, Orang Asli were paid a nominal sum by commercial outfitters seeking wildlife products. The demand for wildlife products had increased over time. For example, pangolins, turtles, porcupines and pythons had lucrative value in traditional Chinese medicine (Brooks et al. 2010; Clements et al. 2010). Today, the huge market had encouraged the Orang Asli to hunt threatened or endangered species even though they knew about the wildlife protection laws. Based on personal communication, more than 50% of the respondents in this study were aware about which animal they could and could not hunt. However, the hunting of protected animals still occurred due to lack of economic opportunities or incentives. Therefore, the low socioeconomic status of the orang Asli that led to a high illiteracy rate and lack of marketable skills had left them desperate and vulnerable (Azrina et al. 2011).

There was some disparity between the species that the Orang Asli were allowed to hunt and those that they actually hunted. For instance, even though Orang Asli communities hunted critically endangered species like the sunda pangolin and red-eared slider, they also hunted small arboreal animals like squirrels, which were not in the Sixth Schedule. According to Aziz et al. (2013), there were weaknesses in the law such as the rights given to the Orang Asli and how the animals were chosen. As such, it was important to review the law to make it more relevant and prevent the Orang Asli from getting into trouble. This was supported by previous studies on poaching by rural communities in Sarawak, which identified lax enforcement as one of the causes that encouraged the activity (Kishen et al. 2012).

Conclusion

The Orang Asli community hunted wildlife for both consumption and non-consumption purposes. The community did not cause wildlife depletion or extinction because they did not hunt in an unsustainable manner. While it was vital to conserve the survival of threatened species, efforts should be implemented to sustain the livelihood of the Orang Asli. The current findings showed that wildlife provided a significant livelihood to the Orang Asli, particularly the Semoq Beri in Kenyir, Terengganu. While they were known to hunt in a sustainable manner, more studies should be conducted to address the issue of wildlife hunting not only by the Orang Asli, but also by non-native locals. New economic opportunities for the Orang Asli, alternative incentives to reduce poaching, and maintaining suitable amounts of virgin forest together with increased law enforcement would help secure Malaysia’s wildlife heritage and sustainable lifestyle of the Orang Asli.

References

Anon. (2011). Orang Asli lured into trapping rich pickings. Retrieved from https://news.asiaone.com/News/AsiaOne+News/Malaysia/Story/A1Story20110530-281387.html on 14th April, 2017.

Anon. (2016). Carcass of de-tusked elephant found near Tasik Pedu. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2016/05/03/carcass-of-de-tusked-elephant-found-near-tasik-pedu/ on 14th April, 2017.

Anon. (2017). Two rare elephants killed for ivory in central Sabah. Retrieved from http://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asiapacific/two-rare-elephants-killed-for-ivory-in-central-sabah/3407282.html on 14th April, 2017.

Arnold, J. E. M. & Ruiz, P. M. (1996). Framing the issues relating to non-timber forest products research. Current issues in non-timber forest products research. Proceedings of the Workshop "Research on NTFP" Hot Springs, Zimbabwe 28 August-2 September 1995.

Aziz, S. A., Clements, G. R., Rayan, D. M., & Sankar, P. (2013). Why conservationists should be concerned about natural resource legislation affecting indigenous peoples’ right: Lessons from peninsular Malaysia. Biodiversity and Conservation, 22, 639–656.

Azlan, J. M. & Faisal, F. M. (2006). Ethnozoological survey in selected areas in Sarawak. The Sarawak Museum Journal.

Azliza, M. A., Ong, H. C., Vikineswary, S., Noorlidah, A., & Haron, N. W. (2012). Ethno-medicinal resources used by the Temuan in Ulu Kuang Village. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 6, 17–22.

Azrina, A., Or, O. C., & Kamal, S. F. (2011). Collectors and traders: A study of orang Asli involvement in wildlife trade in the Belum-Temengor complex, Perak. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya.

Balakrishnan, N. (2016). Why are the Orang Asli community some of the poorest in Malaysia? Retrieved from http://says.com/my/news/1-in-5-sabah-bumiputera-households-are-poverty-stricken. Accessed on 4th March, 2017.

Bartholomew, C. V., Muhammad Syamsul, A. A., & Abdullah, M. T. (2016). Orang Asli dan sumber alam. In M. T. Abdullah, M. F. Abdullah, C. V. Bartholomew, & J. Rohana (Eds.), Kelestarian Masyarakat Orang Asli (pp. 45–69). Kuala Nerus: Penerbit Universiti Malaysia Terengganu.

Brooks, E. G. E., Roberton, S. I., & Bell, D. J. (2010). The conservation impact of commercial wildlife farming of porcupines in Vietnam. Biological Conservation, 143, 2808–2814.

Burkill, I. H. (1935). A dictionary of the economic products of the Malayan peninsula. Kuala Lumpur: Department of Agriculture.

Carey, I. (1976). Orang Asli: The aboriginal tribes of peninsular Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Clements, G. R. (2013). The environmental and social impacts of roads in Southeast Asia. In PhD thesis. Cairns: James Cook University.

Clements, G. R., Mark Rayan, D., Ahmad Zafir, A. W., Venkataraman, A., Alfred, R., Payne, J., Ambu, L. N., & Sharma, D. S. K. (2010). Trio under threat: Can we secure the future of rhinos, elephants and tigers in Malaysia? Biodiversity and Conservation, 19, 1115–1136.

Dasgupta, S. (2017). Seven most wanted elephant poachers arrested in Malaysia, Retrieved from https://news.mongabay.com/2017/02/seven-most-wanted-elephant-poachers-arrested-in-malaysia/ on 14th April, 2017.

Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2010). Population and housing census of Malaysia 2010: Preliminary count report. Putrajaya: Department of Statistics Malaysia.

Endicott, K. (2010). The hunting methods of the batek negritos of Malaysia. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 2, 7–22.

Francis, C. M. (2008). A field guide to the mammals of South-East Asia. London: New Holland.

Gianno, R., & Bayr, K. J. (2009). Semelai agricultural patterns: Toward an understanding of variation among indigenous cultures in southern peninsular Malaysia. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 40, 153–185.

Hedges, L., Clements, G. R., Aziz, S. A., Yap, W., Laurance, S., Goosem, M., & Laurance, W. F. (2013). The status of small mammalian carnivores in a threatened wildlife corridor in peninsular Malaysia. Small Carnivore Conservation, 49, 9–14.

Hood, S. (1995). Dunia pribumi dan alam sekitar: Langkah ke hadapan. Bangi: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Howell, C. J., Schwabe, K. A., & Abu Samah, A. H. (2010). Non-timber forest product dependence among the Jah hut subgroup of peninsular Malaysia’s orang Asli. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 12, 1–8.

Indraneil, D. (2010). A field guide to the reptiles of South-East Asia. United Kingdom: New Holland.

IUCN. (2016). IUCN red list of threatened species. Retrieved from http://www.iucnredlist.org/ Accessed on 8th August, 2015.

Kishen, B., Madinah, A., & Abdullah, M. T. (2012). Review and validation of selected materials on illicit hunting in Malaysia. Regional sustainable development in Malaysia and Ausralia. Bangi: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Kuchikura, Y. (1986). Subsistence ecology of a Semoq Beri community, hunting and gathering people of peninsular Malaysia. Hokkaido: Hokkaido University.

Loh, F. F. (2016). Highways open doors to poaching. Retrieved from http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2016/06/29/highways-open-doors-to-poaching-roads-that-cut-across-vital-habitats-pose-a-danger-to-protected-wild/ on 25th June, 2016.

Mainka, S. A. & Trivedi, M. (2002). Links between biodiversity conservation, livelihoods and food security: The sustainable use of wild species for meat. United Kingdom: Switzerland and Cambridge.

Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2012). Interactions between human behavior and ecological systems. Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society of London. Biological Sciences, 367, 270–278.

Milow, P., Malek, S., Nur Shahidah, M., & Ong, H. C. (2013). Diversity of plants tended or cultivated in orang Asli homogardens in Negeri Sembilan, peninsular Malaysia. Human Ecology, 41, 325–331.

Mohd Azlan, J., & Muhammad Faisal, F. (2006). Ethnozoological survey in selected areas in Sarawak. Sarawak Museum Journal, 10, 184–200.

Muhammad Syamsul, A. A., Bartholomew, C. V., & Abdullah, M. T. (2016). Keterancaman dan kelestarian kehidupan masyarakat Orang Asli. In M. T. Abdullah, M. F. Abdullah, C. V. Bartholomew, & J. Rohana (Eds.), Kelestarian masyarakat Orang Asli (pp. 71–84). Kuala Nerus: Penerbit Universiti Malaysia Terengganu.

Nicholas, C. (2000). The Orang Asli and the contest for resources: indigenous politics, development and identity in Peninsular Malaysia. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, Copenhagen, Denmark and Center for Orang Asli Concerns (COAC), Subang Jaya.

Ong, H. C., Faezah, A. W., & Milow, P. (2012a). Medicinal plants used by the Jah hut orang Asli at Kampung Pos Panderas, Pahang, Malaysia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 6, 11–15.

Ong, H. C., Lina, E., & Milow, P. (2012b). Traditional knowledge and usage of edible plants among the Semai community of Kampung Batu 16, Tapah, Perak, Malaysia. Scientific Research and Essays, 7, 441–445.

Rambo, A. T. (1979). Human ecology of the orang Asli: A review of research on the environmental relations of the aborigines of peninsular Malaysia. Federation Museum Journal, 24, 40–71.

Ramle, A., Greg, A., Ramle, N. H., & Mat Rasat, M. S. (2014a). Forest significant and conservation among Semoq Beri tribe of orang Asli in Terengganu state. Malaysia. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 8, 386–395.

Ramle, A., Asmawi, I., Mohamad Hafis, A. S., Ramle, N. H., & Mat Rasat, M. S. (2014b). Forest conservation and the Semoq Beri community of Terengganu. Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, 10, 113–114.

Robson, C. (2000). A field guide to the birds of South-East Asia. United Kingdom: New Holland.

Rosli, Z. (2016). Fading roar: only 23 tigers left in Terengganu. Retrieved from http://www.nst.com.my/news/2016/12/199678/fading-roar-only-23-tigers-left-terengganu on 14th April, 2016.

Samuel, A. J. S. J., Kalusalingam, A., Chellappan, D. K., Gopinath, R., Radhamani, S., Husain, H. A., & Promwichit, P. (2010). Ethnomedical survey of plants used by the orang Asli in Kampung Bawong, Perak. West Malaysia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 6, 1–6.

Shively, G. (1997). Poverty, technology, and wildlife hunting in Palawan. Environmental Conservation, 24, 57–63.

Tuck-Po, L. (1998). Həp: The significance of forest to the emergence of Batek knowledge in Pahang, Malaysia. Penang: Universiti Sains Malaysia.

Wildlife Conservation Act. (2010). Act 716. Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Berhad. Retrieved fromhttp://www.gunungganang.com.my/pdf/MalaysianLegislation/National/Wildlife%20Conservation%20Act%202010.pdf.

Wildlife Conservation Enactment. (1997). Retrieved from http://www.lawnet.sabah.gov.my/lawnet/SubsidiaryLegislation/WildlifeConservation1997(Regulations1998).pdf. on 28th March, 2016.

Wildlife Protection Ordinance. (1998). Retrieved from http://www.sarawakforestry.com/pdf/laws/wildlife_ protection_ordinance98_chap26.pdf.

Yahaya, F. H. (2015). The usage of animals in the lives of the Lanoh and Temiar tribes of Lenggong, Perak. Retrieved from http://www.shs-conferences.org/articles/shsconf/abs/2015/05/shsconf_icolass2014_04006/shsconf_icolass2014_04006.html on 16th September, 2015.

Yeng, A. C. (2010) WWF: Orang Asli being used. Retrieved from http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2010/02/10/wwf-orang-asli-being-used/ on 20th April, 2016.

Yong, D. L. (2015). Persistence of primate and ungulate communities on forested islands in Lake Kenyir in northern peninsular Malaysia. Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society, 61, 7–14.

Zarina, A. (2016). Three man arrested after discovery of tiger carcasses in toilet, Retrieved from http://www.nst.com.my/news/2016/01/123320/three-men-arrested-after-discovery-tiger-carcass-toilet.

Zuraina, M. (1982). The west mouth, Niah, in the prehistory of south-East Asia. Sarawak Museum Journal, 31, 1–20.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Trans Disciplinary Research Grant Scheme (TRGS/2015/59373). We acknowledge the permission and assistance provided by the Management Council of Terengganu State Park, Lembaga Kemajuan Terengganu Tengah (KETENGAH), Forestry Department and the Wildlife and National Parks Department (PERHILITAN) [Permit No: 100-34/1.24 Jld 4 (10)]. Many thanks to the Orang Asli Development Department (JAKOA) and all villagers of Kampung Sungai Berua, Terengganu, for their cooperation. Last but not least, the authors thank Muhammad Fuad Abdullah, Muhamad Aidil Zahidin, Muhammad Syamsul Aznan Ariffin, Hairul Nizam Mohd Khori and Nurul Faezah Azizan for helping in the field work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Apendix 1 List of mammals Recorded in Kenyir Forest (Yong 2015; Clements 2013; Hedges et al. 2013)

Apendix 1 List of mammals Recorded in Kenyir Forest (Yong 2015; Clements 2013; Hedges et al. 2013)

Family | Species | Common Name | WCA (2010) | IUCN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Manidae | Manis javanica | Sunda pangolin* | TP | CR |

Cercopithecidae | Presbytis siamensis | White-thighed leaf monkey | P | NT |

Trachypithecus obscurus | Dusky leaf monkey* | P | NT | |

Macaca nemestrina | Pig-tailed macaque* | P | VU | |

Macaca fascicularis | Long-tailed macaque* | P | LC | |

Hylobatidae | Symphalangus syndactylus | Siamang | TP | EN |

Hylobates lar | White-handed gibbon | TP | EN | |

Canidae | Cuon alpines | Dhole | TP | EN |

Ursidae | Helarctos malayanus | Sun bear | TP | VU |

Mustellidae | Martes flavigula | Yellow-throated Marten | TP | LC |

Lutrogale perspicillata | Smooth-coated otter | TP | VU | |

Aonyx cinereus | Oriental small-clawed otter | TP | VU | |

Viverridae | Viverra zibetha | Large Indian civet | TP | VU |

Viverra tangalunga | Malay civet* | P | LC | |

Prionodon linsang | Banded linsang | TP | LC | |

Paradoxurus hermaphrodites | Common palm civet | P | LC | |

Paguma larvata | Masked palm civet | TP | LC | |

Arctictis binturong | Binturong | TP | VU | |

Arctogalidia trivirgata | Small-toothed palm civet | TP | LC | |

Hemigalus derbyanus | Banded palm civet | TP | NT | |

Herpestidae | Herpestes urva | Crab-eating mongoose | TP | LC |

Felidae | Pantera tigris jacksoni | Malayan Tiger | TP | EN |

Panthera pardus | Leopard | TP | NT | |

Neofelis nebulosa | Clouded leopard | TP | VU | |

Pardofelis marmorata | Marbled cat | TP | NT | |

Catopuma temminckii | Golden cat | TP | NT | |

Prionailurus bengalensi | Leopard cat | TP | LC | |

Elephantidae | Elephas maximus | Asian elephant | TP | EN |

Tapiridae | Tapirus indicus | Asian tapir | TP | EN |

Suidae | Sus scrofa | Wild pig* | P | LC |

Tragulidae | Tragulus spp. | Mousedeer* | P | LC |

Tragulus kanchil | Lesser mouse-deer* | NA | LC | |

Cervidae | Rusa unicolor | Sambar deer* | P | VU |

Muntiacus muntjak | Barking deer* | P | LC | |

Bovidae | Capricornis sumatraensis | Serow | TP | VU |

Sciuridae | Callosciurus prevostii | Prevost’s squirrel | TP | LC |

Callosciurus caniceps | Grey-bellied squirrel | NA | LC | |

Lariscus insignis | Three-striped ground squirrel | NA | LC | |

Muridae | Rattus spp. | Rats | NA | LC |

Hystricidae | Hystrix brachyura | Malayan porcupine* | P | LC |

Atherurus macrourus | Brush-tailed porcupine | P | LC | |

Echinosorex gymnura | Moonrat | NA | LC |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bartholomew, C.V., Zainir, M.I., Nor Zalipah, M., Husin, M.H., Abdullah, M.T. (2021). Wildlife Hunting Practices by the Indigenous People of Terengganu, Peninsular Malaysia. In: Abdullah, M.T., Bartholomew, C.V., Mohammad, A. (eds) Resource Use and Sustainability of Orang Asli. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64961-6_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64961-6_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-64960-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-64961-6

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)