Abstract

Sexual minority men (SMM), including gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, experience disproportionately high rates of trauma, including childhood sexual abuse (CSA), intimate partner violence, and chronic trauma in the form of stigma and discrimination. In this chapter we will (1) broadly explore trauma including types of trauma impacting SMM, (e.g., CSA, intimate partner violence, stigma, and discrimination); (2) briefly review existing evidence-based trauma treatments and their limitations for SMM; (3) present a treatment rationale, description, and preliminary results for cognitive behavioral therapy for trauma and self-care (CBT-TSC), an intervention that aims to address trauma and sexual health concerns among SMM; and (4) discuss implications of and future directions for CBT-TSC.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Background

Sexual minority men (SMM), including gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, experience disproportionately high rates of trauma, including childhood sexual abuse (CSA), intimate partner violence, and chronic trauma in the form of stigma and discrimination. In this chapter we will 1) broadly explore trauma including types of trauma impacting SMM, (e.g., CSA, intimate partner violence, stigma, and discrimination); 2) briefly review existing evidence-based trauma treatments and their limitations for SMM; 3) present a treatment rationale, description, and preliminary results for cognitive behavioral therapy for trauma and self-care (CBT-TSC), an intervention that aims to address trauma and sexual health concerns among SMM; and 4) discuss implications of and future directions for CBT-TSC.

Historically, psychosocial intervention research has focused on treatments targeting one problem (e.g., trauma or depression). However, given the interrelated nature of many problems impacting SMM with traumatic life experiences and the need to deliver effective interventions with constrained resources, this narrow approach is insufficient (Westen, Novotny, & Thompson-Brenner, 2004). This approach may not be optimal in the case of SMM’s health given the numerous interrelated psychosocial health threats facing this group. This chapter describes how trauma defined broadly impacts SMM. Further, we emphasize the need to create and assess transdiagnostic interventions that simultaneously reduce interrelated, or syndemic (Stall et al., 2003), conditions facing SMM at the level of their shared psychosocial pathways. We then describe CBT-TSC, an intervention designed for SMM with histories of CSA to treat trauma and increase self-care behaviors, including HIV risk reduction. This chapter positions minority stress as a key driver of these shared pathways and suggests intervention principles and techniques that can address the pathways through which minority stress yields interrelated health threats for SMM.

Trauma

Determining what qualifies as a traumatic event can be difficult, with the definition of trauma varying with context. Broadly, a traumatic event is considered an extremely stressful experience that may result in PTSD. Notably, many individuals who experience a traumatic event do not develop PTSD. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) , defines a traumatic event as an experience or event that includes experiencing, witnessing, or having to deal with actual or threatened death, serious injury, or physical or sexual violence to the individual or someone else (DSM-5, 2013). Diagnostically, PTSD is characterized by four unique symptom clusters: re-experiencing the event, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, and arousal. An individual may re-experience the traumatic event through memories, flashbacks, and dreams, and emphasis is placed on symptoms occurring more than once in a defined period of time. Avoidance is characterized by an active dismissal of thoughts, memories, or feelings and can also include avoidance of places or people that bring on recollections of the event. Negative cognitions and mood encompass the individuals’ feeling of themselves, others, and the world, as well as consistently depressed or apathetic affect. Finally, arousal includes hypervigilance, risky and/or self-destructive behavior, and distractibility. These symptom clusters need to be present at least 1 month after the traumatic event for a diagnosis of PTSD to be made (DSM-5, 2013).

Types of Trauma Impacting SMM

Childhood Sexual Abuse

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is a type of early-life trauma that has alarming prevalence rates in SMM. Many studies conducted in the United States have attempted to quantify the rate of CSA experienced by SMM, with estimations ranging from 20% to 39.7% (Doll et al., 1992; Lenderking et al., 1997; Mimiaga et al., 2009; Paul, Catania, Pollack, & Stall, 2001), astoundingly higher than estimates between 5% and 10% among the general male population (Finkelhor, 1994). In addition to increased risk for developing PTSD, SMM who have experienced CSA are more likely to report lower self-efficacy and poorer communication skills around issues of safe sex (Mimiaga et al., 2009). History of CSA has also been associated with increased rates of fear, anxiety, depression, anger, and aggression. These negative psychological states can create impactful long-term effects, including decreased self-esteem, as well as increased experiences with stigma, isolation, and substance use (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986).

CSA among SMM has been associated with sexual risk-taking behavior in later life (O’Leary, Purcell, Remien, & Gomez, 2003; Stall et al., 2003). Specifically, SMM who experienced CSA were more likely to have higher rates of unprotected receptive anal intercourse and were more likely to participate in risky sex compared to those who did not experience CSA (Lenderking et al., 1997; Paul et al., 2001). While CSA is considered a risk factor for HIV infection, traditional HIV prevention interventions may not be as efficacious for individuals who have a history of CSA due to the high prevalence of co-occurring psychosocial conditions (Halkitis, Wolitski, & Millet, 2013; Mimiaga et al., 2009; Safren, Reisner, Herrick, Mimiaga, & Stall, 2010; Mimiaga et al., 2015).

Other Interpersonal Victimization

In addition to being disproportionately affected by CSA , SMM are more likely to experience other interpersonal victimizations related to increased risk of developing PTSD compared to other men, including rape in adulthood and intimate partner violence (Pantalone, Rood, Morris, & Simoni, 2014; Pantalone, Schneider, Valentine, & Simoni, 2012; Schumm, Briggs-Phillips, & Hobfoil, 2006). A 2011 review conducted by Rothman, Exner, and Baughman reported that 12–54% of SMM had experienced sexual assault in their lifetime. A better understanding of how interpersonal trauma impacts SMM and how treatment strategies can most effectively meet the needs of the victims and reduce the perpetration of intimate partner violence is needed.

Stigma

Though not always conceptualized as a form of trauma, experienced stigma and discrimination have been shown to elicit traumatic responses (Ferlatte, Hottes, Trussler, & Marchand, 2014; Geibel, Tun, Tapsoba, & Kellerman, 2010). Stigma is often related to sexual minority or HIV status and can be related to internalized homonegativity, criminalization of same sex behaviors, perceptions of HIV, and discrimination based on sexual orientation. Meyer’s (1995, 2003) minority stress model provides a theoretical framework for how experiences of discrimination and stigma can put an individual at risk for physical and mental health issues later in life. The model postulates that internal and external stressors faced by many sexual minority individuals predispose those individuals to mental health concerns, such as PTSD. When a sexual minority individual experiences stigma and discrimination, maladaptive coping strategies can form, creating vulnerability for depression, anxiety, expectations of rejection, negative cognitions about oneself, difficulty regulating emotions, and other reactions that are associated with traumatic experiences (Batchelder, Ehlinger, et al., 2017; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 1995, 2003).

Intersecting Stigma and Discrimination

In addition to sexual minority stigma, discrimination based on racial and ethnic minority identity, which can intersect with stigma and discrimination based on sexual identity, can greatly impact mental health and HIV-related outcomes among SMM. These outcomes, which include depression, anxiety, and a higher prevalence of sexual risk-taking, may be related to negative attitudes toward homosexuality—specifically same sex behaviors and perceived femininity of SMM—among minority populations (Choi, Hans, Paul, & Ayala, 2011; Han, Proctor, & Choi, 2014; Jeffriesm, Marks, Lauby, Murrill, & Millet, 2013). In support of this theory, Glick, Cleary, and Golden (2015) found that racial and ethnic minority respondents to the General Social Survey experienced more negative attitudes toward sexual minorities than their white counterparts .

Existing Evidence-Based Trauma Interventions

The American Psychological Association strongly recommends four psychotherapy interventions for treating PTSD: cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, prolonged exposure therapy, and cognitive processing therapy, and conditionally recommends eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, brief eclectic psychotherapy, narrative exposure therapy, and medications (American Psychological Association, 2017). While all the strongly recommended intervention strategies are based on or derived from cognitive behavioral therapy, the conditionally recommended interventions are more divergent. For example, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy is a structured therapy that involves briefly focusing on the traumatic memory while concurrently experiencing stimulation bilaterally (i.e., eye movements), which has been associated with a reduction in the vividness of the traumatic memories and the associated emotions (Shapiro, 2017).

Of the strongly recommended treatments for PTSD, there are similarities and key differences. Cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD focuses on changing patterns of behaviors, thoughts, feelings related to current symptoms, and problems leading to difficulties in functioning (Monson & Schnaider, 2014). Relatedly, cognitive therapy aims to interrupt disturbing thought and behavioral patterns that interfere with an individual’s life via modifying negative evaluations of traumatic memories (Ehlers et al., 2014). Prolonged exposure is a specific type of cognitive behavioral therapy that teaches individuals to confront fears through gradually approaching trauma-related emotions, memories, and situations (Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 1998). This cognitive behavioral therapy involves individuals working with their therapist to face stimuli and situations in a safe and graduated manner to evoke fear reminiscent of the trauma in order to ultimately reduce their fear and increase their comfort (e.g., Schnurr et al., 2017; Powers et al., 2010). This therapy is helpful for those whose traumas activate the fear response; however, this may be less helpful for those with subclinical experiences of trauma. Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) is grounded in cognitive behavioral therapy and information processing theory and includes components of psychoeducation, imagined exposure, and cognitive reprocessing (Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2014; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2016). Notably, CPT does not require activation of the fear response and, therefore, may be helpful for those with subclinical experiences of trauma. Early support for the efficacy of CPT was provided by Resick and Schnicke (1992) in the treatment of PTSD in rape victims and military-related trauma (Monson et al., 2006). When compared to a minimal attention condition, CPT was highly efficacious and superior in reducing PTSD symptoms to the minimal attention condition, comparable to prolonged exposure (Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002).

Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) has been effective in treating posttraumatic stress, including trauma related to CSA, and has been adapted for a range of problems. Originally developed to treat the symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims, more recently Resick et al. (2008) reported on the relative efficacy of the components of cognitive processing therapy in effecting clinically significant reductions in trauma symptoms. Owens, Pike, and Chard (2001) reported that CPT for sexual abuse was associated with significant reductions in severity of cognitive distortions, which maintained through 1 year of follow-up. CPT has also been effective in reducing symptoms of PTSD more broadly related specifically to sexual abuse that maintained for up to 1 year (Chard, 2005). In addition to its application to treat victims of sexual assault, CPT has been successfully adapted for specific application to treat PTSD in combination with comorbid depression (Nishith, Nixon, & Resick, 2005) and comorbid panic disorder (Falsetti, Resnick, & Davis, 2005; Falsetti, Resnick, & Lawyer, 2006). Further, CPT has been shown to be an efficacious treatment for PTSD among incarcerated adolescent males (Ahrens & Rexford, 2002) and in men with acute stress disorder who had been the victims of anti-gay violence (Kaysen, Lostutter, & Goines, 2005).

Existing Trauma Interventions for SMM

Though trauma treatment has been well researched in the general population—including empirically tested techniques such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive reprocessing therapies, prolonged exposure therapy, and CPT—many of the proposed treatments have not been applied to sexual minority populations and the unique interrelated trauma experiences they face (Cohen, Mannarino, & Beblinger, 2006; Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007; Resick & Schnicke, 1992; Shapiro, 1989). One reason for this dearth may be the possibility that trauma is underreported in sexual minority populations, as certain types of victimization may not be identified or conceptualized as traumatic by clients (Hardt & Rutter, 2004; Littleton, Rhatigan, & Axsom, 2007). Furthermore, clinicians may hesitate to assess trauma directly in SMM clients, despite the prevalence for multiple traumas and re-victimization experienced by this population (Ard & Makadon, 2011; Pantalone et al., 2012; Pantalone et al., 2014; Sweet & Welles, 2011). The work we present here, including proof of concept and pilot results, is perhaps the strongest evidence in favor of the suitability of components of cognitive therapy and CPT to treat childhood sexual abuse symptoms in SMM with current sexual risk for HIV .

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Trauma and Self-Care (CBT-TSC) Treatment Rationale

Conceptual Model: How Developmental Trauma Vulnerabilities Lead to Adult Vulnerabilities for PTSD and Other Disorders

We put forth a conceptual model , informed by previous work, to convey how vulnerabilities associated with developmental trauma may lead to adult vulnerabilities for PTSD and other disorders disproportionately experienced by SMM (e.g., depression, substance use disorders, and HIV). The EXPLORE intervention, which included some skill-building but was predicated on participants’ perceptions that they could change their behavior, indicated that these strategies might not have been robust enough to change patterns of internalized anger, depression, and lack of self-efficacy that may have been long-standing in the participants who experienced CSA (Exner, Meyer-Bahlburg, & Ehrhardt, 1992; Kelly et al., 1993; Quadland & Shattls, 1987). EXPLORE demonstrated that depression was significantly more prevalent among SMM with a history of CSA compared to those without. In addition, SMM with a history of CSA versus those without were more likely to use illicit substances and alcohol. Further, as the EXPLORE intervention had less effect than hypothesized in reducing HIV infection rates, we surmised that the presence of CSA history in SMM may interfere with their ability to derive benefit from traditional HIV prevention interventions (Mimiaga et al., 2009). These results suggest that additional effort may be needed to go beyond traditional HIV prevention interventions with this population to reduce HIV incidence, as sexual risk-taking among SMM with a history of CSA is the result of syndemics, or synergistically interrelated issues including mental health and substance use disorders among SMM (Stall et al., 2003).

This work provided several specific insights that influenced the proposed conceptual framework. Specifically, it indicated that future behavioral interventions for SMM with histories of CSA may need to incorporate counseling and skills-building that together address the traumatic memories and coping strategies that ensue after young men are abused. Addressing these together is especially important given the high prevalence of these childhood experiences and their role in potentiating sexual risk-taking behavior.

Therapeutic Rationale and Logic of the Integrated Treatment

The experience of being sexually traumatized during childhood or early adolescence may substantially interfere with adult sexual development later in life in a way that places SMM at increased risk for HIV. The four symptom clusters of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) highlight how this may occur. They include (1) highly distressing intrusive thoughts, memories, and flashbacks of the sexual trauma; (2) avoidance of emotions, thoughts, and situations related to the trauma; (3) negative cognitions and/or mood; and (4) hyperarousal—inconsistent and chronic triggering of the biological alarm system.

The intrusive thoughts and negative emotions contribute to very high levels of fear and distress, which may be particularly salient in sexual situations. The intrusive thoughts are often related to negative cognitions about one’s self as a result of having been sexually abused (i.e., self-blame, self-loathing, disgust, guilt) which are avoided either through dissociation, substance use, or other avoidant coping strategies. This avoidant stance, in adult sexual situations, can compromise self-care generally and sexual health specifically by interfering with the ability to identify risk, negotiate safer sex, and assert safety behaviors.

Hyperarousal , a maladaptive attempt to cope with repeated distressing intrusions, leads to chronic activation of the startle response, feeling on guard, irritable, and angry, and interferes with the ability to distinguish safe from unsafe situations. In sexual situations, the symptoms of hyperarousal impede the ability to make accurate and realistic sexual risk appraisals. This leads to loss of self-efficacy as the individual doubts his ability to identify risk or his ability to take steps to offset it.

The purpose of CBT-TSC is therefore to retrain individuals to adequately think through the childhood sexual trauma in a more adaptive way (i.e., change appraisals, identify thinking errors, restructure negative cognitions about self) and to participate in behavioral experiments to practice self-care and to restructure problematic thoughts in the functional contexts in which they occur. We hypothesize that after successful cognitive restructuring of the childhood sexual trauma combined with active rehearsal of healthful behaviors the individual will be bothered less by intrusive thoughts and emotions, be better able to cope with those intrusions when they occur, and so be less likely to engage in avoidance in sexual situations. In addition, as distress and intrusions subside, so will the symptoms of hyperarousal which are no longer needed. Thus, the natural cues for safety and risk will become more accessible to the participant, and he will be able to make more accurate sexual safety and risk appraisals. When this is combined with behavioral rehearsals of safety behaviors in sexual situations (as specified in the treatment protocol), the participant will be better able to achieve benefit from the specific behavioral skills training for reducing unsafe sex that is integrated into each session of the intervention. Hence, the successful outcome of this intervention will be improved sexual health behavior though more adaptive management of sexual risk for HIV and STIs and improved general mental health though the reduction of symptoms of PTSD .

The CBT-TSC Intervention

The purpose of this integrated cognitive behavioral intervention, adapted for HIV-uninfected SMM with histories of CSA, is to retrain individuals to develop more realistic appraisals of the childhood sexual trauma, identifying thinking errors, restructuring negative cognitions about self, and increasing self-efficacious behavior. As such, the intervention integrates sexual risk reduction counseling with some components of cognitive therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for trauma and self-care (CBT-TSC) strategies to address trauma symptom severity and sexual risk for HIV. CBT-TSC has been specifically piloted on SMM with CSA histories and sexual risk to reduce interfering negative CSA-related thoughts about self, to appraise sexual risk more accurately, and to decrease avoidance of sexual safety considerations through rehearsals of sexual safety behaviors. The intervention is designed to address the three pathways to sexual risk. Risk reduction counseling targets the direct pathway by specifying an implementation plan for sexual behavior change. CBT-TSC addresses the cognitive pathway (changing appraisals, restructuring negative cognitions) to risk by generating more realistic risk estimates and increasing self-efficacy. By reducing intrusion-related distress, we impact the behavioral pathway by reducing the need for avoidant behaviors (avoidant coping, drug use, dissociation). Through more realistic evaluations of self and less distress in sexual situations, the participant can approach the realities of sexual risk appraisal and implement plans for sexual safety with increased self-efficacy and without avoidance .

Description of CBT-TSC Modules

Module 1: Psychoeducation/Resource Building

The goal of this module is to educate the client with respect to posttraumatic stress reactions and increase distress tolerance. The therapist interactively reviews posttraumatic symptom clusters with the client and normalizes trauma reactions and other anxiety feelings. This includes a review and specification of the client’s distress coping strategies and plan for use of adaptive strategies. During these initial therapy sessions, the patient is educated about the symptoms of PTSD and identifies the sexual abuse event(s) in addition to initial problem areas. Concurrently, the patient learns how to identify and describe both thoughts and feelings as well as understand the relationships between them. This phase of treatment aids patients in the generation of a written account of the meaning and interpretations he places on the abuse event, consistent with impact statements described in cognitive processing therapy (CPT; Resick et al., 2002; Resick et al., 2008; Resick & Schnicke, 1992).

Module 2: Cognitive Restructuring

During this module, the client is supported to increase confidence around identifying cognitions in sexual situations. The therapist maintains a safe environment for the client to discuss CSA. Specific therapeutic tasks include reviewing impact statements and working interactively with the client to identify and specify cognitive distortions about self that were present during sexual situations, consistent with CPT (Resick & Schnicke, 1992; Resick et al., 2002; Resick et al., 2008). If necessary, the therapist addresses avoidance related to completing the impact statement as homework and works with the patient to generate an impact statement in session through interactive dialogue. In this phase of treatment, the therapist also introduces the broader rationale, which involves completing a worksheet with the patient that requires the patient to identify a situation that elicits a cognitive distortion and related emotions. This requires the patient to evaluate critically their cognitive distortions, which often involves referencing the range of cognitive distortions often endorsed by people with developmental trauma histories. In collaboration with the therapist, the patient then generates alternatives to the cognitive distortions with the goal of generating realistic, measured, and qualified alternative thoughts. The patient then identifies the emotions associated with these thoughts. The general strategy is not just to restructure or relearn specific distorted thoughts but to identify distorted thoughts more generally in order to be able to apply this skill across multiple thoughts and situations. The focus on sexual (health) situations and related cognitions in nonsexual situations is maintained. During this phase of treatment, the patient also learns how to identify cognitive distortions, particularly with respect to distortions about self (e.g., self-blame, self-guilt). The patient learns strategies for challenging and reprocessing these distortions .

Module 3: Behavioral Experiments

In this module, the patient learns the rationale for behavioral experiments, works interactively with the therapist to identify specific relevant behavioral experiments, identifies behavioral and cognitive barriers to the behavioral experiment, and makes plans to offset behavioral barriers and restructure cognitive barriers in session. The inclusion of behavioral experiments is designed to provide a functional learning context in which the patient will most appropriately apply cognitive restructuring skills. This is an important step in learning to apply cognitive restructuring strategies in the actual situations where these interfering and distressing thoughts are elicited. Work is done antecedent and consequent to the event, which involves the anticipation of the experience and debriefing afterward. The treatment plan allows for three behavioral experiments to be planned and debriefed .

Module 4: Intimacy/Relationship Issues

The final sessions focus on consolidating the patient’s cognitive therapy skills, with a particular focus on areas potentially disrupted by the sexual abuse experience. These content areas are largely informed by and modified from the insightful work completed by Resick and colleagues in the specification and efficacy tests of CPT (Resick et al., 2002; Resick et al., 2008; Resick et al., 2014; Resick et al., 2016; Resick & Schnicke, 1992). These content areas have been adapted specifically to be relevant and applicable to SMM with developmental trauma and sexual risk behavior. These sessions were designed to be modular, whereby the therapist and patient together identify areas that are especially relevant and focus the final sessions on addressing those issues. This allows for individualizing the intervention while staying within the confines of the treatment manual.

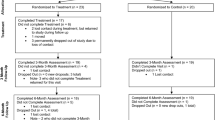

CBT-TSC Pilot

The CBT-TSC intervention was initially conducted with four participants in a proof-of-concept study (O’Cleirigh, 2010) and then piloted in a small randomized controlled trial (n = 43; O’Cleirigh et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2017), both conducted at Fenway Health, a community health center specializing in sexual and gender minority healthcare in Boston, Massachusetts. The methodology and detailed results are described elsewhere (O’Cleirigh et al., 2019). Eligibility for both included identifying as a man who has sex with men, experienced CSA (i.e., sexual contact before the age of 13 with an adult or person 5 years older or sexual contact with the threat of force or harm between the ages of 13 and 16 inclusive with a person 10 years older), being HIV-uninfected, and engaging in risky sexual behavior (operationalized as two or more episodes of condomless anal intercourse with serodiscordant partners in the past 6 months). Participants were not required to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD. The ten-session CBT-TSC intervention, which included HIV testing and counseling, was compared to a two-session HIV testing and counseling-only approach with immediate, 6-month, and 9-month follow-up visits.

Across both the proof-of-concept study and the pilot study, participants reported reductions in condomless sex post-treatment. In the pilot RCT, participants in the CBT-TSC condition had significantly greater reductions in condomless sex, trauma symptoms, and specifically avoidance compared to those in the control condition. Further, the reductions in condomless sex were maintained at follow-up visits for those in the CBT-TSC condition. Together, these pilot results provided initial evidence for the efficacy of integrated cognitive behavioral trauma treatment for populations, specifically sexual minorities, who are vulnerable to multiple, intertwined mental health concerns. A full-scale multi-site randomized controlled trial was recently completed (The THRIVE Study, R01MH095624, PI O’Cleirigh; Boroughs et al., 2015; Batchelder, Ehlinger, et al., 2017; Batchelder, Safren, et al., 2017). Further, a version of this intervention adapted for SMM living with HIV is currently being piloted at Fenway Health and Ryerson University (O’Cleirigh, 2018; O’Cleirigh & Hart, 2018). Together, CBT-TSC, which leverages psychoeducation related to sexual health and existing evidence-based trauma-treatment approaches, offers a promising intervention for SMM with histories of CSA.

Implications of Pilot Data

This body of work presents the utility for addressing interrelated, or syndemic, psychological challenges to offsetting new HIV infections and improving sexual health self-care among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Cognitive behavioral therapy for trauma and self-care (CBT-TSC) not only works to address health behaviors but also addresses the impediments to those health behaviors. By working to improve sexual self-care as well as treating trauma symptom severity among SMM with developmental trauma, CBT-TSC has the potential to be more effective within a real-world context where syndemic or interrelated psychosocial problems perpetuate HIV acquisition and poor engagement in HIV self-care (Singer, 1996; Stall et al., 2003). This is consistent with the increasing emphasis on transdiagnostic flexible interventions being used to address presumed underlying psychological processes (e.g., Barlow et al., 2010; Pachankis, 2015). Transdiagnostic treatment aims to address basic underlying processes thought to be common across syndemic, or synergistically interrelated, issues including mental health and substance use disorders among SMM. Both Barlow et al., (2010) and Pachankis (2015) have tested transdiagnostic interventions to address such processes hypothesized to be linked to causative or maintaining variables. For example, Pachankis has aimed to address processes linking minority stress to HIV risk behavior, including maladaptive emotion regulation, negative thinking styles, low levels of self-efficacy, and avoidance coping (Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Jonathon, Safren, & Parsons, 2015). Pachankis has utilized the Unified Protocol (Barlow et al., 2010), a transdiagnostic cognitive behavioral therapy that can be applied to a range of different psychological disorders and problems (e.g., various anxiety disorders as well as depression). In addition to interventions consistent with the minority stress theory as expanded by Hatzenbuehler and Pachankis, future interventions may benefit from addressing other underlying vulnerabilities common across mental health and substance use diagnostic categories, such as distress intolerance, interpersonal rejection sensitivity, posttraumatic reactions, and internalized stigma (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Pachankis, Rendine, Restar, Ventuneac, & Parsons, 2015).

Although the encouraging findings for the trials reported here are preliminary, they may suggest the importance of ensuring that there is sufficient treatment dose (in this case ten 1-hour individual treatment sessions) to address sexual behavior that may place our clients at risk for HIV, in the context of childhood sexual abuse histories and in many cases additional adult mental health and substance use concerns. More traditional brief sexual risk reduction programs may lack sufficient dose to change patterns of internalized anger, depression, and lack of self-efficacy that may have been long-standing in participants who experienced CSA and underlie unhealthy patterns of sexual behavior. While more work is needed to determine the ideal combination of skills-building and psychoeducation needed to provide maximum impact on behavior change, by leveraging existing evidence-based trauma-treatment approaches in conjunction with psychoeducation related to sexual health, CBT-TSC may have provided a sufficient dose of treatment to address the underlying trauma necessary to enable improving sexual self-care.

The protection afforded to SMM from pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (Chou et al., 2019; Dimitrov et al., 2019; iPrEx Study Team, 2010) identifies it as a key component for safeguarding the sexual health of SMM. However, as histories of childhood sexual abuse may interfere with the ability of SMM to modify their sexual behavior to protect their sexual health, it is likely that posttraumatic stress responding may also interfere with their access and adherence to, and sustained use of, biomedical HIV prevention options including PrEP (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019; iPrEx Study Team, 2010; Nikolopoulos, Christaki, Paraskevis, & Bonovas, 2017). The emergence of streamlined PrEP delivery models (Coelho, Torres, Veloso, Landovitz, & Grinsztejn, 2019), increased availability of PrEP (Hoornenborg, Krakower, Prins, & Mayer, 2017; Sullivan, Mena, Elopre, & Siegler, 2019), and increased availability of programs that support its use nationwide (Carnevale et al., 2019; Hoth et al., 2019) will all help to minimize structural, systemic, and clinic-level barriers to PrEP use. Cognitive behavioral interventions that address the posttraumatic and other mental health barriers to PrEP uptake and use among SMM can help support delivery of PrEP and improve the sexual health of this vulnerable group.

Implementation and Dissemination

Encouragingly, there are now several protocolized treatments with initial evidence supporting their use specifically designed to promote the mental health of sexual minority men (Mimiaga et al., 2019; O’Cleirigh et al., 2019; Pachenkis et al., 2019). The work to provide full efficacy support for these innovative programs is currently under way. The important implementation science work that will support the uptake of these evidence-based treatments into the community and mental health centers where sexual minority men can access them must then be undertaken. The extent to which this work will be successful will be determined by the extent to which these treatments are evaluated using culturally competent therapists, working in community settings, with treatments that are cost-effective to the settings in which they are offered and sustainable within the context of the supports available with the healthcare system.

These implementation hurdles are also complicated by the fact that sexual minority men may experience additional barriers that interfere with their access to, and uptake of, mental health services (Batchelder, Ehlinger, et al., 2017; Batchelder, Safren, et al., 2017; Ferlatte et al., 2019). Many of these barriers are best understood in terms of sexual minority specific stress. Although, encouragingly, there have been recent attempts to provide guidelines and recommendations for both clinical training programs and professional certifications (Boroughs et al., 2015) for psychologists and other clinicians working with sexual and gender minorities. Nevertheless, the availability of appropriately trained clinicians, with cultural competency for providing behavioral health services to sexual minorities, is very limited (Lyons, Bieschke, Dendy, Worthington, & Georgemiller, 2010).

Conclusions

The development and initial testing of this integrated treatment for PTSD symptom severity and self-care (CBT-TSC) among SMM with histories of childhood sexual abuse are presented here as an innovative treatment platform. This treatment recognizes both the complexity of the mental health problems facing SMM and the devastating health disparity for HIV that they experience. The development of these effective integrated treatments that are also sensitive to the settings and contexts in which they will be implemented has the potential to significantly improve the mental health of SMM and also to help offset new HIV infections.

References

Ahrens, J., & Rexford, L. (2002). Cognitive processing therapy for incarcerated adolescents with PTSD. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma, 6(1), 201–216.

American Psychological Association. (2017). PTSD treatments. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/treatments/index.aspx

Ard, K. L., & Makadon, H. J. (2011). Addressing intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(8), 930–933.

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Fairholme, C. P., Ellard, K. K., Boisseau, C. L., Allen, L. B., et al. (2010). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Batchelder, A. W., Ehlinger, P. P., Boroughs, M. S., Shipherd, J. C., Safren, S. A., Ironson, G. H., et al. (2017). Psychological and behavioral moderators of the relationship between trauma severity and HIV transmission risk among MSM with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 40(5), 794–802.

Batchelder, A. W., Safren, S., Mitchell, A. D., Ivardic, I., & O’Cleirigh, C. (2017). Mental health in 2020 for men who have sex with men in the united sates. Sexual Health. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH16083

Boroughs, M. S., Valentine, S. E., Ironson, G. H., Shipherd, J. C., Safren, S. A., Taylor, S. W., et al. (2015). Complexity of childhood sexual abuse: Predictors of current post-traumatic stress disorder, mood disorders, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors among adult men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(7), 1891–1902.

Browne, A., & Finkelhor, D. (1986). Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological Bulletin, 99(1), 66–77.

Carnevale, C., Zucker, J., Borsa, A., Northland, B., Castro, J., Molina, E., et al. (2019). Engaging a predominately Latino community in HIV prevention: Laying the groundwork for pre-exposure prophylaxis and HIV sexual health programs. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNC.0000000000000121

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). HIV basics: PrEP. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prep.html#targetText=Pre%2Dexposure%20prophylaxis%20(or%20PrEP,sex%20or%20injection%20drug%20use

Chard, K. M. (2005). An evaluation of cognitive processing therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 965–971.

Choi, K. H., Hans, C. S., Paul, J., & Ayala, G. (2011). Strategies for managing racism and homophobia among U.S. ethnic and racial minority men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 23(2), 145–158.

Chou, R., Evans, C., Hoverman, A., Sun, C., Dana, T., Bougatsos, C., …, Korthuis, P. T. (2019). Pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection: A systematic review for the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542888/

Coelho, L. E., Torres, T. S., Veloso, V. G., Landovitz, R. J., & Grinsztejn, B. (2019). Pre-exposure prophylaxis 2.0: New drugs and technologies in the pipeline. Lancet HIV. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30238-3.

Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Beblinger, E. (2006). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press.

Dimitrov, D., Moore, J. R., Wood, D., Mitchell, K. M., Li, M., Hughes, J. P., et al. (2019). Predicted effectiveness of daily and non-daily PrEP for MSM based on sex and pill-taking patterns from HPTN 067/ADAPT. Clinical Infectious Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz799

Doll, L. S., Joy, D., Bartholow, B. N., Harrison, J. S., Bolan, G., Douglas, J. M., et al. (1992). Self-reported childhood and adolescent sexual abuse among adult homosexual bisexual men. Child Abuse and Neglect, 16(6), 855–864.

Ehlers, A., Hackmann, A., Grey, N., Wild, J., Liness, S., Albert, I., et al. (2014). A randomized controlled trail of 7-day intensive and standard weekly cognitive therapy for PTSD and emotion-focused supportive therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 294–304.

Exner, T. M., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1992). Sexual self-control as a mediator of high risk sexual behavior in a New York City cohort of HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay men. Journal of Sex Research, 29, 389–406.

Falsetti, S. A., Resnick, H., & Davis, J. (2005). Multiple channel exposure therapy: Combining cognitive-behavioral therapies for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder with panic attacks. Behavior Modification, 29(1), 70–94.

Falsetti, S. A., Resnick, H. S., & Lawyer, S. R. (2006). Combining cognitive processing therapy with panic exposure and management techniques. In L. A. Schein, H. I. Spitz, G. M. Burlingame, P. R. Muskin, & S. Vargo (Eds.), Psychological effects of catastrophic disasters: Group approaches to treatment (pp. 629–668). New York: Haworth Press.

Ferlatte, O., Hottes, T. S., Trussler, T., & Marchand, R. (2014). Evidence of a syndemic among young Canadian gay and bisexual men: Uncovering the associations between anti-gay experiences, psychosocial issues, and HIV risk. AIDS & Behavior, 18(7), 1256–1263.

Ferlatte, O., Salway, T., Rice, S., Oliffe, J. L., Rich, A. J., Knight, R., et al. (2019). Perceived barriers to mental health services among Canadian sexual and gender minorities with depression and at risk for suicide. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(8), 1313–1321.

Finkelhor, D. (1994). The international epidemiology of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 18(5), 409–417.

Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1998). Treating the trauma of rapeL cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. New York: Guilford Press.

Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2007). Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences-therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press.

Geibel, S., Tun, W., Tapsoba, P., & Kellerman, S. (2010). HIV vulnerability of men who have sex with men in developing countries: Horizon studies. Public Health Reports, 125(2), 316–324.

Glick, S. N., Cleary, S. D., & Golden, M. R. (2015). Brief report: Increasing acceptance of homosexuality in the United States across racial and ethnic subgroups. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 70(3), 319–322.

Halkitis, P. N., Wolitski, R. J., & Millett, G. A. (2013). A holistic approach to addressing HIV infection disparities in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. American Psychologist, 68(4), 261–273.

Han, C.-S., Proctor, K., & Choi, K.-H. (2014). We pretend like sexuality doesn’t exist: Managing homophobia in Gaysian America. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 22(1), 53–63.

Hardt, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 260–273.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730.

Hoornenborg, E., Krakower, D. S., Prins, M., & Mayer, K. H. (2017). Pre-exposure prophylaxis for MSM and transgender persons in early adopting countries. AIDS, 31(16), 2179–2191.

Hoth, A. B., Shafer, C., Dillon, D. B., Mayer, R., Walton, G., & Ohl, M. E. (2019). Iowa TelePrEP: A public-health-partnered telehealth model for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) delivery in a rural state. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001017

iPrEx Study Team. (2010). Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. The New England Journal of Medicine, 363, 2587–2599.

Jeffriesm, W. L., Marks, G., Lauby, J., Murrill, C. S., & Millet, G. A. (2013). Homophobia is associated with sexual behavior that increases risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV infection among black men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 17(4), 1442–1453.

Kaysen, D., Lostutter, T. W., & Goines, M. A. (2005). Cognitive processing therapy for acute stress disorder resulting from anti-gay assault. Cognitive Behavioral Practice, 12(3), 278–289.

Kelly, J. A., Murphy, D. A., Bahr, G. R., Kalichman, S. C., Morgan, M. G., Stevenson, L. Y., et al. (1993). Outcome of cognitive-behavioral and support group brief therapies for depressed, HIV-infected persons. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(11), 1679–1686.

Lenderking, W. R., Wold, C., Mayer, K. H., Goldstein, R., Losina, E., & Seage, G. R. (1997). Childhood sexual abuse among homosexual men: Prevalence and association with unsafe sex. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 12(4), 250–253.

Littleton, H. L., Rhatigan, D., & Axsom, D. (2007). Unacknowledged rape: How much do we know about the hidden sexual assault victim? Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 14(4), 57–74.

Lyons, H., Bieschke, K., Dendy, A., Worthington, R., & Georgemiller, R. (2010). Psychologists’ competence to treat lesbian, gay and bisexual clients: State of the field and strategies for improvement. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41, 424–434.

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38–56.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

Mimiaga, M. J., Noonan, E., Donnell, D., Safren, S. A., Koenen, K. C., Gortmaker, S., et al. (2009). Childhood sexual abuse is highly associated with HIV risk-taking behavior and infection among SMM in the EXPLORE study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 51(3), 340–348.

Mimiaga, M. J., O’Cleirigh, C., Biello, K. B., Robertson, A. M., Safren, S. A., Coates, T. J., et al. (2015). The effect of psychosocial syndemic production on a 4-year HIV incidence and risk behavior in a large cohort of sexual active men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 68(3), 329–336.

Mimiaga, M. J., Pantalone, D. W., Biello, K. B., Hughto, J. M. W., Frank, J., O’Cleirigh, C., et al. (2019). An initial randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation for treatment of concurrent crystal methamphetamine dependence and sexual risk for HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men. AIDS Care, 31(9), 1083–1095.

Monson, C. M., & Schnaider, P. (2014). Treating PTSD with cognitive-behavioral therapies: Interventions that work. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Monson, C. M., Schnurr, P. P., Resick, P. A., Friedman, M. J., Young-Xu, Y., & Stevens, S. P. (2006). Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 898–907.

Nikolopoulos, G. K., Christaki, E., Paraskevis, D., & Bonovas, S. (2017). Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV: Evidence and perspectives. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 23(18), 2579–2591.

Nishith, P., Nixon, R. D. V., & Resick, P. A. (2005). Resolution of trauma-related guilt following treatment of PTSD in female rape victims: A result of cognitive processing therapy targeting comorbid depression? Journal of Affective Disorders, 86(2–3), 259–265.

O’Cleirigh, C. (2010). Development and pilot study of integrated trauma treatment and sexual risk reduction in sexual risk-taking MSM with a history of childhood sexual abuse. San Francisco, CA: Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies Convention.

O’Cleirigh, C. (2018). Adverse childhood events and trauma-informed HIV care. Plenary address to the Ontario HIV Treatment Network HIV endgame 3 conference. Toronto, Canada.

O’Cleirigh, C., & Hart, T. (2018). Development of an empirically support treatment for trauma and adaptive engagement in HIV care. Workshop presented to the Ontario HIV Treatment Network HIV Endgame 3 Conference. Toronto, Canada.

O’Cleirigh, C., Safren, S. A., Taylor, S. W., Goshe, B. M., Bedoya, C. A., Marquez, S. M., et al. (2019). Cognitive behavioral therapy for trauma and self-care in men who have sex with men with a history of childhood sexual abuse: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS and Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02482-z

O’Leary, A., Purcell, D., Remien, R. H., & Gomez. (2003). Childhood sexual abuse and sexual transmission risk behavior among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Care, 15(1), 17–26.

Owens, G. P., Pike, J. L., & Chard, K. M. (2001). Treatment effects of cognitive processing therapy on cognitive distortions of female child sexual abuse survivors. Behavior Therapy, 32, 413–424.

Pachankis, J. E. (2015). A transdiagnostic minority stress treatment approach for gay and bisexual men’s syndemic health conditions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1843–1860.

Pachankis, J. E., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Jonathon, H., Safren, S. A., & Parsons, J. T. (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 875–889.

Pachankis, J. E., Rendine, H. J., Restar, A., Ventuneac, A., & Parsons, J. T. (2015). A minority stress—Emotion regulation model of sexual compulsivity among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Health Psychology, 34, 829–840.

Pachenkis, J. E., McConocha, E. M., Reynolds, J. S., Winston, R., Adeyinka, O., Harkness, A., et al. (2019). Project ESTEEM protocol: A randomized controlled trial of an LGBTQ-affirmative treatment for young adult sexual minority men’s mental and sexual. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1086.

Pantalone, D. W., Rood, B. A., Morris, B. W., & Simoni, J. M. (2014). A systematic review of the frequency and correlates of partner abuse in HIV-infected women and men who partner with men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 25(1 Suppl), S15–S35.

Pantalone, D. W., Schneider, K. L., Valentine, S. E., & Simoni, J. M. (2012). Investigating partner abuse among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 16(4), 1031–1043.

Paul, J. P., Catania, J., Pollack, L., & Stall, R. (2001). Understanding childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of sexual-risk taking among men who have sex with men: The urban men’s health study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 25(4), 557–584.

Powers, M. B., Halpern, J. M., Ferenschak, M. P., Gillihan, S. J., & Foa, E. B. (2010). A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(6), 635–641.

Quadland, M. C., & Shattls, W. D. (1987). AIDS, sexuality, and sexual control. Journal of Homosexuality, 14, 277–298.

Resick, P., & Schnicke, M. K. (1992). Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(5), 748–756.

Resick, P. A., Galovski, T. E., O’Brien, U. M., Scher, C. D., Clum, G. A., & Young-Xu, Y. (2008). A randomized clinical trial to dismantle components of cognitive processing therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in female victims of interpersonal violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 243–258.

Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., & Chard, K. M. (2014). Cognitive processing therapy: Veteran/military version therapist and patient materials manual. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., & Chard, K. M. (2016). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual. New York: Guilford Press.

Resick, P. A., Nishith, P., Weaver, T. L., Astin, M. C., & Feuer, C. A. (2002). A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 867–879.

Rothman, E. F., Exner, D., & Baughman, A. L. (2011). The prevalence of sexual assault against people who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual in the United States: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12(2), 55–66.

Safren, S. A., Reisner, S. L., Herrick, A., Mimiaga, M. J., & Stall, R. D. (2010). Mental health and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 55(Suppl 2), S74–S77.

Schumm, J. A., Briggs-Phillips, M., & Hobfoil, S. E. (2006). Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among inter-city women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(6), 825–836.

Schnurr, P. P, Firedman, M. J., Engel, C. C., Foa, E. B., Shea, M. T., Chow, B. K., Resick, P. A., Thurston, V., Orsillo, S. M., Haug, R., Turner, C., & Bernardy, B. (2017). Cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(8), 820–830.

Shapiro, F. (1989). Efficacy of the eye movement desensitization procedure in the treatment of traumatic memories. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2(2), 199–223.

Shapiro, F. (2017). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.). New York: Guildford Press.

Singer, M. (1996). A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: Conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 24(2), 99–110.

Stall, R., Millis, T. C., Williamson, J., Hart, T., Greenwood, G., Paul, J., et al. (2003). Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 93(6), 939–942.

Sullivan, P. S., Mena, L., Elopre, & Siegler, A. J. (2019). Implementation strategies to increase PrEP update in the south. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 16(4), 259–269.

Sweet, T., & Welles, S. L. (2011). Associations of sexual identity or same-sex behaviors with history of childhood sexual abuse and HIV/STI risk in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 59, 400–408.

Szekeres, G., Coates, T. J, Frost, S., Arleen Leibowitz, A., & Shoptaw, S. (2004). Anticipating the efficacy of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and the needs of at risk Californians. Center for HIV identification, prevention, and treatment services (CHIPTS). Retrieved from http://www.uclaisap.org/assets/documents/PreP_Report_FINAL_11_1_04.pdf

Taylor, S. W., Goshe, B. M., Marquez, S. M., Safren, S. A., & O’Cleirigh, C. (2017). Evaluating a novel intervention to reduce trauma symptoms and sexual risk taking: Qualitative exit interviews with sexual minority men with childhood sexual abuse. Psychology Health and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1348609

Westen, D., Novotny, C. M., & Thompson-Brenner, H. (2004). The empirical status of empirically supported psychotherapies: Assumptions, findings, and reporting in controlled clinical trials. Psychological Bulletin, 130(4), 631–663.

Acknowledgements

R01MH095624-01 and R34MH081760-02 from National Institute of Mental Health supported the projects noted in this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

O’Cleirigh, C., Batchelder, A.W., McKetchnie, S.M. (2021). Contextualizing Evidence-Based Approaches for Treating Traumatic Life Experiences and Posttraumatic Stress Responses Among Sexual Minority Men. In: Lund, E.M., Burgess, C., Johnson, A.J. (eds) Violence Against LGBTQ+ Persons. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52612-2_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52612-2_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-52611-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-52612-2

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)