Abstract

Compromising smoking cessation applications’ effectiveness, many users relapse. We propose that long-term adoption of persuasive technology is (partly) dependent on users’ motivational orientation. Therefore, we studied the potential relationship between user’s achievement motivation and the long-term behavior change effectiveness of persuasive technology. One-hundred users of a smoking cessation app filled out a questionnaire assessing their motivational orientation and (long-term) behavior change rates. Based on research findings, we expected that participants with stronger learning goal orientation (who are focused on self-improvement and persistent when facing failure) would report a higher long-term behavior change success rate. In contrast, we expected that participants with a stronger performance goal orientation (focused on winning, for whom solitary failures can undermine intrinsic motivation) would report lower long-term success. Results confirmed our hypotheses. This research broadens our understanding of how persuasive applications’ effectiveness relates to user achievement motivation.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Health risks associated with smoking are well studied and reported. Research shows that smoking is one of the factors leading to acute conditions such as lung cancer and cardiovascular diseases [1]. A high majority of smokers realize health risks associated with smoking, and consequently try to quit, however, fails in the effort [2]. There are different methods available for smokers to quit, for example, instructional and conditioning methods. A recent trend in helping smokers quit is through the use of smoking cessation applications (apps). These apps are designed to support smokers quit smoking through tracking, self-monitoring and distracting them from smoking [3]. It can be reasoned that most of the smoking cessation apps are designed based on the principles of Persuasive Technology (PT). PTs are technologies that are designed to change peoples’ attitudes and/or behaviors without the use of coercion or deception [4, 5]. PTs have the potential to be used as a tool for preventive health engineering. PTs have already shown potential in supporting people to live with healthy lifestyle and can therefore help prevent a wide range of medical conditions [6, 7]. Although PTs are promising in promoting healthy behaviors, actual behavior change effectiveness is often limited. The limited effectiveness of smoking cessation apps could be explained by the finding that most of these apps are not grounded in theory [8]. Still, recent research indicates that smoking cessation apps that are designed using behavior change theories are also not proving to be very successful [9].

One major challenge for preventive health through the use of PT is to be able to change human behavior over a longer period of time. It is frequently highlighted in literature that PTs for smoking cessation show promise however the effect is rather short-term. To date, it is hard to find a study that has evaluated and reported long-term effectiveness of smoking cessation apps. Some of the research studies underscore that long-term effectiveness of PTs for behaviors such as smoking does not even exist [10]. Therefore, the area relating to the long-term effectiveness of PTs in behavior change still calls for further research. In this study, we investigated whether there was a correlation between users’ motivations and long-term effectiveness of PTs.

Smoking remains the common most preventable cause of acute illnesses in the modern world [11, 12]. PTs can play an important role in addressing this problem. This could be, for example, done through developing apps to support individuals to quit. Fogg [4], explains the mechanisms of using computing devices through the functional triad. The functional triad can be easily incorporated in a smoking cessation apps. As a tool, an app can help individuals track statistics on the number of cigarettes smoked, as a media, an app can present immediate feedback on health-related consequences and as a social actor, an app can provide support, for example, through goal-setting, rewards, feedback and even social support. One of the challenges for smoking cessation is that it cannot be studied as a “single act of observable behavior”. In contrast to less frequent behaviors, smoking brings in the factor of behavior change process and it is therefore that some researchers argue that persuasion through technology should be studied as a long-term process [13].

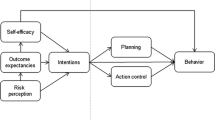

To the best of our knowledge, research on the long-term effectiveness of PTs is scarce. Among the few, one study examined long-term effectiveness of wearable devices for promoting fitness. This study concludes that users who adhere with PTs for a longer period of time have different needs especially because they are expected to move a step further towards maintaining a positive behavior [10]. The same could be the case with users of smoking cessation apps. However, it is a highly contextualized and personalized area of study. Ubhi et al. [9] studied smoking cessation apps and observed that 81% of the users stopped using the app after just four weeks, which is an evidence of a low adherence rate. Extended adherence is essential for any kind of behavior change as it is inherently a long-term process. Experts from other disciplines including psychology and social sciences have worked to understand the reasons for short-term adoption of technologies that promote healthy behaviors. The most cited work in this area is Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). According to TAM, whether an individual has an intention to adopt a technology depends on two major factors i.e. perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use [13]. TAM has been extended by including a third factor called social influence and it has been further integrated with models of technology acceptance [14] and used for investigating acceptance of persuasive robots [28]. We argue that TAM is not particularly useful when it comes to determining why people stay motivated in using PTs in the long run. Firstly, TAM explains only about 40% of variance in adoption [15]. Secondly, the model is used to explain whether or not an individual has an intention to start using a specific technology. Our argument is that initial adoption of a technology is not sufficient enough to help understand why individuals continue or discontinue to use that particular technology. It is therefore that we believe that long-term adoption of a given PT leading to achievement of sustained behavior change largely depends on individual users’ motivations. To investigate our hypothesis, we referred to the theory of Achievement Motivation [16].

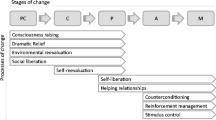

Little if any research is available on what motivates people to use and adhere with PTs. Earlier researchers have postulated that adaptive motivational patterns play an important role in long term success of a certain goal [17]. These patterns are behavioral in nature and facilitate founding, continuing and achieving those goals that have high value for individuals [17]. Dweck’s framework highlights two types of achievements: Learning Goals and Performance Goals. Of the two, learning goals aim at improving one’s abilities to perform better. For example, to quit smoking could be seen as a learning goal for an individual to quit smoking would mean that the individual has to prepare to quit smoking by learning and mastering the skills needed for such a behavior change. Performance goals on the other hand can be seen as making a stricter target. For example, planning to quit smoking by the end of the month. According to [18], adoption of learning goals generally leads to better motivational patterns as compared with adoption of performance goals [18]. Another, related theoretical framework distinguishes three types of goals i.e. (i) Learning Goals, (ii) Performance-approach Goals and Performance-avoidance Goals [19]. According to this framework, individuals position themselves either around improving their competence or display an avoidance attitude. Simply put, the two approaches are either aimed at achieving a goal with self-confidence to be successful (through a learning goal or a performance-approach goal) or avoiding working towards a goal anticipating fear of failure (through a performance-avoidance goal) [19]. They argue that adoption of approach-oriented goals often leads to high motivation when compared with adoption of avoidance-oriented goals [19].

Subsequently, approach-oriented goals lead to formation of behaviors that are centered on positive outcomes. If this stands true, then it can be safely argued that approach-oriented goals improve task engagement and greater potential of mastering a skill. According to [20], the approaches towards goals depend on the context. One possible explanation would be that performance approach goals are more likely to avoid failures. However, changing from a learning goal to performance goal is less likely to happen as failures do not necessarily undermine learning goals. In the context of smoking cessation, if an individual with a performance goal experiences relapse after quitting, there is a chance that in the next attempt the individual might focus on avoiding another relapse rather than focusing on continuing quitting. On the contrary, if the same individual had set a learning goal, the chance of shifting towards performance avoidance might be far less because a relapse would not undermine the original goal. On the other hand, performance-approach goals can lead to high performance and adaptive motivational patterns when individuals experience a phase of success. One study shows that those individuals who had set performance-approach goals actually scored higher grades than those who had set learning goals [21]. This is an interesting finding and reveals that learning goals are not always as effective as advocated.

To sum up, learning goals are linked with high intrinsic and adaptive motivational patterns that is characterized by high persistence. The performance-avoidance goals have a detrimental effect on motivational patterns and performance and lastly, performance-approach goals can result in either negative or positive outcomes in terms of motivational behaviors. It is important to note that majority of research on achievement goals was carried out in the field of Education, Workplace and Sports [22, 23]. Adoption of achievement goals and its relation to sustained success in the area of PT for healthy behaviors is not yet studied.

2 Objectives

This paper sets the first step towards investigating a possible connection between achievement motivation and PT behavior change effectiveness. Theories on achievement motivation assert that challenges in behavior change could be tackled if individuals had adaptive motivational patterns. Such motivational patterns are linked to setting learning goals, and goals that are approach oriented. We therefore inferred that there might be a link between the type of goal and the long-term success that an individual might experience through the use of PTs. We also investigated a possible connection between goal types and success that individuals experience when using smoking cessation apps. The objective is to identify whether there is any correlation between the type of achievement goals and their long-term success through the use of PT. The following research question is therefore developed:

What is the relationship between users’ achievement motivation and the effectiveness of Persuasive Technology (smoking cessation app) for attaining sustained (long-term) behavior change?

To investigate the research question, we conducted an online survey where participants reported their smoking cessation success, the type of achievement motivation that they had and their demographical contexts. Through the analysis of a possible relationship between participants’ smoking cessation success and their achievement motivation helped come up with the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 1a: Individuals who score higher on learning goals and performance-approach goals also have a higher success rate in smoking cessation.

-

Hypothesis 1b: Individuals who score higher on performance-avoidance goals have a lower success rate in smoking cessation.

Earlier studies have shown that adoption of performance-avoidance goals is unfavorable for intrinsic motivation and task performance when compared with the adoption of performance-approach goals and learning goals [19, 20]. We assumed that people who score high on performance avoidance goals to have less chance to quit smoking when compared with people who score higher on performance approach and learning goals. Our assumption creates further hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 2a: Individuals who score higher on learning goals stay smoke free for longer period of time.

-

Hypothesis 2 b: Individuals who score higher on performance approach and performance avoidance approach goals stay smoke free for shorter period of time.

3 Methods

An a priori power analysis using G* Power [24] indicated that we needed no less than 82 participants in order to have 80% power for detecting a medium sized correlation with a two-tailed significance level of .05. A total of 100 (32 M, 68 F) participants took part in the study. All the participants were proficient at the English language. In addition, all participants were trying to quit smoking or had tried to quit. In addition, all participants used a smoking cessation app to receive support in quitting smoking.

Recruitment was carried out through two different channels. First, participants were recruited through a social media page “Smoke Free” from Facebook. This page hosted a community who can find support to quit smoking. We posted a link to the survey on this page regularly for a period of two months describing the objectives of the research. Second, a group of participants were recruited at shopping malls and public transport stations. Potential participants were asked if they had ever used a smoke cessation app. Those who had used such apps were given access to the link to the survey and requested to register their responses. Participants who clicked the link were directed to the survey where a brief overview of the research was presented advising the participants about the objectives, expected duration to complete the survey and data confidentiality policy. To ensure that data is not duplicated, participants had to log in using their emails in order to fill out the survey. Subsequently, participants were asked about the type/s of apps that they had used for smoking cessation. An option of “None” was included for those who had never used an app. The following three pages of the survey, participants responded to questions about their smoking behaviors, achievement goals, and their demographic context. On an average, it took six (6) minutes for the participants to complete the survey. No monetary rewards were offered to the participants.

To examine participants’ smoking behaviors while using the Smoke Free app, we included questions on smoking behavior in the survey. The questions were based on previous studies [25, 26]. As there was no clear consensus in earlier studies on how smoking cessation is measured, we decided to use a combination of questions to construct a reliable measure. In all, seven (7) questions targeted smoking behaviors to measure success and persistence. A factor analysis and analysis of Cronbach’s Alpha rendered two (2) measures for smoking cessation performance. The first measure of performance was the sum of answers to four (4) questions that indicated the success rate experienced by participants. These measures showed high internal consistency (Cronbach Alpha = .84) based on the following four questions:

How many relapses did you experience while using the app?

Did you smoke since the intended day of quitting?

Do you smoke less after adopting to use the app?

Did you successfully quit smoking using the app?

The second measure of performance indicated the length of duration that participants managed to stay smoke free. Participants responded whether they had remained smoke free for less than a week, from a week to one month and from one to three months. The duration of staying smoke free was used to measure the long-term performance in order to test our second hypothesis. The third measure focused on participants’ adoption of learning, performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals while trying to quit smoking. For this purpose, we applied an adaptation of the Achievement Goal Questionnaire developed by [21]. This questionnaire was used to examine the types of achievement goals that university students adopted for a Psychology class while the performance goal items measured their motivation to perform well in the class compared to other students and contained six questions per goal types. While the classroom context is highly different from smoking cessation context however we believe that it suited our study as participants could still be motivated to perform well when compared to other people in their quest to quit smoking. Further, the subject at hand is unique in the sense that instead of learning Psychology, participants of this study had an opportunity to learn more about smoking cessation. For these reasons, we rephrased the items developed by [21] in order to fit the study context.

A factor analysis confirmed that the items could be divided into three independent groups. Some of the items from the Achievement Goal questionnaire did not load high on either of the three factors and were therefore dropped. Subsequent calculations of Cronbach’s Alpha showed that the adaption of achievement goals questionnaire rendered three internally consistent measures. First, a learning goal was calculated by averaging the score on five learning goal questions with a high reliability (Cronbach Alpha = .94). A performance-approach goal measure was calculated by averaging the scores on five performance-approach goal items that showed high reliability (Cronbach Alpha = .91). A performance-avoidance goal measure was calculated by averaging the scores on two performance-avoidance goal items that showed significant reliability (Cronbach Alpha = .84). Since the achievement goal items were rephrased versions of the original items constructed by [21], the items were developed slightly different from the original ones based on the context of the study. The factor analyses for internal consistency helped us come up with three components. According to [27] several demographic measures are closely connected to the success rate for to smoking cessation. Participants answered 11 questions on the demographical circumstances that might impact their smoking behavior. These items were used for control variables as well as for validating measures that we developed by comparing results to earlier studies. Important demographic variables include the participant’s age, whether or not they have other smokers in their family, their desire to quit smoking and whether or not they have invested money to buy the smoking cessation app.

4 The Smoking Cessation App

All participants [n = 100] used a smoking cessation app in their quest to quit smoking. Majority of participants (89%) used the Smoke Free app that had main features comprising of a dashboard, diary and progress screen. Table 1 presents the means, standard deviation, observed ranges, possible ranges and reliabilities for the main areas of interest for this study. On an average, participants were highly successful in their quest to quit smoking using the app. Three quarters of the participants indicated to be not smoking at the time they completed the survey. In addition, most of the participants seemed to have a learning goal-oriented approach with a mean average learning goal score of 3.92 on a scale from 1 to 5.

5 Results

Results of the study provided partial support for hypothesis 1a, which stated that individuals who score high on learning goals and performance-approach goals are more likely to have higher success rate in smoking cessation. In line with hypothesis 1a, participants who scored higher on the learning goal measure also scored higher on success rate, as indicated by a first order Spearman rank correlation which is controlled for the effects of performance-avoidance goals, r(97) = .17, p = .092. Not confirming hypothesis 1a, we observed no meaningful correlation between performance-approach goal scores and success rate. Likewise, we observed insignificant zero-order correlations between success rate and learning goals or performance-approach goals. Results supported hypothesis 1b that stated that individuals who score higher on performance-avoidance goals will have lower success rate in smoking cessation. In line with hypothesis 1b, participants who scored higher on performance-avoidance goals scored lower success rates as indicated by a first order Spearman rank correlation r(97) = −.18, p = .074. There was no support for hypothesis 2a which stated that individuals who score higher on learning goals to be smoke free for longer time period. That is, results showed no meaningful correlation between learning goals scores and the amount of time that participants reported to be smoke free. Finally, results showed partial evidence supporting hypothesis 2b, which stated that individuals who score higher on performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals to be smoke free for a shorter time period. In line with hypothesis 2b, participants who scored higher on performance-avoidance goals reported less often to be smoke free for a long period of time, as indicated by partial Spearman rank correlation r(96) = −.18, p = .078. Contrary to hypothesis 2b results did not show a correlation between performance-approach goals and the amount of time that participants reported to be smoke free.

The results indicate that the recruitment strategy had a highly significant relationship with success rate, t (98) = −5.21, p < .00001, with participants who were recruited through social media having higher scores. On an average, participants in the study were successful with 54 out of 100 scoring the maximum 12 points on our measure for success rate. On average, the participants had a success rate of 9.22 on a scale from 0 to 12. Most of these participants were recruited through social media. A small group of participants were recruited by approaching them in person. Highly significant zero order correlations were found between measures for smoking cessation success rate and four items from the demographic questionnaire. Firstly, participants who had indicated high desire to quit smoking scored high on success rate, r = .54, p < .01. Secondly, participants with a higher income also scored high on success rate, r = .35, p < .01. Thirdly, older participants scored high success rates, r = .27, p < .01. Fourthly, participants who smoked more cigarettes prior to the quitting attempt had a higher success rate, r = .38, p < .01. Except for the number of cigarettes smoked per day, the findings of this study are in line with previous research on smoking cessation. In the presented study, we noticed that participants who smoked more cigarettes before attempting to quit had higher income, a higher desire to quit and more often used a paid app. This could be one explanation for why participants who smoke more were more successful. We also found significant differences in success rates for gender and whether participants used a free app or a paid one. Females were more successful when compared with males, t (97) = −2.93, p < .001. In addition, participants who indicated that they paid for the apps were more successful when compared with those who used free smoking cessation apps, t (98) = −3.81, p < .001.

6 Discussion

In this study, we investigated achievement goals and whether they can contribute to quit smoking for a longer period of time. Our major focus was on the first three months of effects of achievements goals because the majority of smokers give up their pursuit and get back to smoking during this time period. Previous research on achievement goals shows that certain types of goals are more beneficial for persistent behaviors. Learning goals [21] have shown to lead to higher performance and intrinsic motivation. We conducted an online survey with participants who had used a smoking cessation app. The participants reported on their smoking behaviors while using the app, and we measured their achievement goals (learning goal and performance goals) and demographic contexts. Supporting our hypotheses, results showed that participants who scored higher on the learning goal measure also reported to have a higher success rate. Results also indicated that participants who scored higher on performance-avoidance goals reported to have a lower success rate. Additionally, participants who scored higher on performance-avoidance goals reported less often to be smoke free for a long period of time. Overall, the results from the current study suggest that the existing theories of achievement goals [21] can be generalized to the context of smoking cessation and PT.

Based on the results, we propose that people in the early stage of smoking cessation can benefit more from adopting learning goals. Learning about smoking cessation could prepare people to quit by developing quitting strategies that they could later apply in the process of quitting and in case of relapse. When people are fully prepared to quit smoking, they might benefit from performance-approach goals. However, further studies are called for to validate this proposition. In this study, we did not make any distinction between different stages of smoking cessation that is indeed a limitation. This study adds significant value to the field of PT as a first step towards investigating a possible relationship between achievement goals and long-term success of PTs (apps). The majority of research in the area of PT focuses on short term adoption, which we believe is a limitation to the field itself. Furthermore, studies that investigated success rates of smoking cessation apps do not investigate why some people are more successful than others using the same app or technology and long-term effect and use of PTs is also not well studied [10]. By recruiting both recent adopters and long-term users of a smoking cessation app, we took the first step towards investigating reasons of failure within the first few months of using such technologies. However, since we did not follow up participants for a longer period of time, extended duration remains another limitation of this study. However, we did try to include people with different levels of success and found indicators that achievement goals of users to impact long term success.

Also, the current results suggest that personalization of persuasive technology (see e.g., [29]) improves its effectiveness. That is, included in the design of technology (and all contexts) are elements that activate certain goals. The current results show that fitting (personalizing) this technology to user characteristics might be beneficial.

This study provides evidence that partitioning of learning goals, performance-avoidance goals and performance-approach goals [21] can be applied in the field of behavior change and PT. The results indicate that further research on the relationship between achievement goals and quality of life could be promising. Finally, this study highlights the negative effects of performance-avoidance goals and that these can be applied in the context of behavior change and PT. The results confirm these effects in the short term and provide an indication of the same for medium to long term. We believe that these findings add value for PT researchers who investigate ways to improve quality of life through continued long-term healthy behaviors.

References

Bauer, U.E., Briss, P.A., Goodman, R.A., Bowman, B.A.: Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet 384(9937), 45–52 (2014)

Chapman, S., MacKenzie, R.: The global research neglect of unassisted smoking cessation: causes and consequences. PLoS Med. 7(2), e1000216 (2010)

Valdivieso-López, E., et al.: Efficacy of a mobile application for smoking cessation in young people: study protocol for a clustered, randomized trial. BMC Public Health 13(1), 704 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-704

Fogg, B.J., Fogg, B.: Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, Amsterdam (2003)

Oinas-Kukkonen, H.: Behavior change support systems: a research model and agenda. In: Ploug, T., Hasle, P., Oinas-Kukkonen, H. (eds.) PERSUASIVE 2010. LNCS, vol. 6137, pp. 4–14. Springer, Heidelberg (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-13226-1_3

Halko, S., Kientz, Julie A.: Personality and persuasive technology: an exploratory study on health-promoting mobile applications. In: Ploug, T., Hasle, P., Oinas-Kukkonen, H. (eds.) PERSUASIVE 2010. LNCS, vol. 6137, pp. 150–161. Springer, Heidelberg (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-13226-1_16

Klasnja, P., Consolvo, S., McDonald, D.W., Landay, J.A., Pratt, W.: Using mobile and personal sensing technologies to support health behavior change in everyday life: lessons learned. In: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, vol. 2009, p. 338. American Medical Informatics Association (2009)

Abroms, L.C., Westmaas, J.L., Bontemps-Jones, J., Ramani, R., Mellerson, J.: A content analysis of popular smartphone apps for smoking cessation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 45(6), 732–736 (2013)

Ubhi, H.K., Kotz, D., Michie, S., van Schayck, O.C., Sheard, D., Selladurai, A., West, R.: Comparative analysis of smoking cessation smartphone applications available in 2012 versus 2014. Addict. Behav. 58, 175–181 (2016)

Fritz, T., Huang, E.M., Murphy, G.C., Zimmermann, T.: Persuasive technology in the real world: a study of long-term use of activity sensing devices for fitness. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 487–496. ACM, April 2014

Mannino, D.M., Buist, A.S.: Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. The Lancet 370(9589), 765–773 (2007)

Oinas-Kukkonen, H., Harjumaa, M.: A systematic framework for designing and evaluating persuasive systems. In: Oinas-Kukkonen, H., Hasle, P., Harjumaa, M., Segerståhl, K., Øhrstrøm, P. (eds.) PERSUASIVE 2008. LNCS, vol. 5033, pp. 164–176. Springer, Heidelberg (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-68504-3_15

Davis, F.: A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems. Theory and results, Doctoral dissertation. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1986)

Venkatesh, V., Davis, F.D.: A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Manage. Sci. 46(2), 186–204 (2000)

Legris, P., Ingham, J., Collerette, P.: Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Inf. Manage. 40(3), 191–204 (2003)

Weiner, B.: An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 92(4), 548 (1985)

Dweck, C.S.: Motivational processes affecting learning. Am. Psychol. 41(10), 1040 (1986)

Heyman, G.D., Dweck, C.S., Cain, K.M.: Young children’s vulnerability to self-blame and helplessness: relationship to beliefs about goodness. Child Dev. 63(2), 401–415 (1992)

Elliot, A.J., Harackiewicz, J.M.: Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: a mediational analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70(3), 461 (1996)

Cury, F., Elliot, A., Sarrazin, P., Da Fonseca, D., Rufo, M.: The trichotomous achievement goal model and intrinsic motivation: a sequential mediational analysis. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 473–481 (2002)

Elliot, A.J., Church, M.A.: A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72(1), 218 (1997)

Van Yperen, N.W., Orehek, E.: Achievement goals in the workplace: conceptualization, prevalence, profiles, and outcomes. J. Econ. Psychol. 38, 71–79 (2013)

Abrahamsen, F.E., Roberts, G.C., Pensgaard, A.M.: Achievement goals and gender effects on multidimensional anxiety in national elite sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 9(4), 449–464 (2008)

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., Lang, A.G.: Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41(4), 1149–1160 (2009)

Freund, K.M., Belanger, A.J., D’Agostino, R.B., Kannel, W.B.: The health risks of smoking - the framingham study: 34 years of follow up. Ann. Epidemiol. 3(4), 417–424 (1993)

Hughes, J.: Motivating and Helping Smokers to Stop Smoking. University of Vermont, Vermont (2003)

Hymowitz, N., Cummings, K.M., Hyland, A., Lynn, W.R., Pechacek, T.F., Hartwell, T.D.: Predictors of smoking cessation in a cohort of adult smokers followed for five years. Tob. Control 6(suppl 2), S57 (1997)

Ghazali, A.S., Ham, J., Barakova, E., Markopoulos, P.: Persuasive Robots Acceptance Model (PRAM): roles of social responses within the acceptance model of persuasive robots. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 1–18 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-019-00611-1

Masthoff, J., Grasso, F., Ham, J.: Preface to the special issue on personalization and behavior change. User Model. User-Adap. Interact. 24(5), 345–350 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-014-9151-1

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ahmet Aman (Eindhoven University of Technology) for important contributions and for running the study, and Mila Davids (Eindhoven University of Technology) for her valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Ham, J., Langrial, S.U. (2020). Learning to Stop Smoking: Understanding Persuasive Applications’ Long-Term Behavior Change Effectiveness Through User Achievement Motivation. In: Gram-Hansen, S., Jonasen, T., Midden, C. (eds) Persuasive Technology. Designing for Future Change. PERSUASIVE 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 12064. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45712-9_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45712-9_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-45711-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-45712-9

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)