Abstract

Coexistence of hunting and wildlife conservation (WLC) is possible if hunting world includes itself in a process of social maturity, which is not only economic but also cultural and educational, to develop a new environmental awareness. Four forms of coexistence between hunting and WLC are examined: non-impactful, impactful and eliminatory, impactful but resilient, and impactful but contributory hunting (ICH). Typical hunter figures are described: venator dominus (owners, etc.), venator socius (associated to a specific district), and venator emptor (who buy rights from time to time). The most significant with regard to its impacts on wildlife, on the environment, and on local communities is ICH. This includes anti-poaching surveillance, monitoring, local community projects that seek improvement in residents’ social conditions (economic and cultural), and coexistence with ecotourism. Trophy hunting needs special attention because there are several critical elements but also various reasons to support a coexistence with WLC. In any case, the aware hunter must contribute to conservation but also concern himself with the economic, social, and cultural problems of those who live in the areas within which he hunts. Five case studies of hunting related to positive or critical consequences to conservation are examined: Italy, Wetlands, Oregon (USA), the Safari Club International, and trophy hunting in sub-Saharan Africa.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Hunting is the activity of killing or trapping wildlife or feral animals or tracking them with the intent of doing so.

This is the current definition but a more precise one can be “the set of activities that aim to take possession of a wild or feral animal, in order to have it permanently but for various purpose (food, economic, recreational, amateur, scientific etc.).”

Stressing that this represents the exploitation use of a renewable resource, hunting and related activities are an art of the ecosystem services (ES), i.e., in a certain way, the services that nature is able to provide to society. These services are implicit (i.e., they exist in themselves, such as atmospheric CO2 regulation by vegetation) or explicit (i.e., they depend on human activities of various kinds, such as hunting) (Buckley and Mossaz 2015; Di Minin et al. 2013b; Crosmary et al. 2015a).

The ownership of wildlife is normally attributable to the state or to the owner of the land where the animal usually lives (or finds itself in that particular moment). In some cases, wild animals can be considered res nullius, that is, not belonging to anyone until their capture or killing (this applies to all traditional or subsistence survival types of hunting). Game may also take the form of collective, feudal, or religious property or belong to public bodies other than the state or even to private bodies other than the state (as in the case of concessions issued by the state to private collective organizations involved in hunting management).

The problem of property arises, however, with regard to species of a certain importance, such that they constitute a genuine resource for which rules are necessary to regulate their appropriation.

In conclusion, hunting always requires the deprivation of liberty or the death for the hunted subject as well as a change of ownership or its reinforcement (if the hunter is also the owner of the fauna), even if such cases are largely conditioned by various regulations.

Poaching is illegal or non-permitted hunting.

Hunting is licit only if codified by written rules. The same hunting may be licit, if it is allowed under traditional and cultural behaviors. This is the case for many traditional hunting methods, as well as for those few populations that do not have legislation in this regard.

The species that are hunted are referred to as “game” and are usually mammals or birds.

However, we talk about hunting even in the case of specific reptiles (in particular the crocodile in Africa and Australia; see Webb et al. 2004). Furthermore, the sport hunting of snakes is not unknown (the Python Challenge in the Everglades, promoted in Florida by the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, a challenge with the aim of capturing as many pythons as possible). Other reptiles and amphibians are normally hunted by all native populations.

In the case of fish and other organisms living in an aquatic environment (with the exception of marine mammals) such as mollusks, crustaceans, etc., we talk about “fishing” (Giles 1978), even if basically it is the same activity.

2 Conservation of Fauna (Wildlife Stricto Sensu and Its Ecosystem Services)

Wildlife (WL) is a renewable resource. In this sense, its sustainable exploitation, that is to say for as long as possible, is a guarantee of its preservation to the extent that the benefits brought about by the exploitation itself involve a large number of subjects. These benefits may include provisioning services (indicators: meat from hunting, value of game, etc.), regulatory services (indicators: pest control, number of IAS, invasive alien species, etc.), and cultural services (indicators: number of hunters, ecotourism operators, etc.) (Andersson et al. 2007; Bateman et al. 2013; Bauer et al. 2009; Freeman 2003; Jeffers et al. 2015; Mace et al. 2012; Tallis et al. 2008; Western 1984).

The evaluation of the WL, in several aspects (not just hunting), allows an appreciation of the natural capital, and this should be considered by the different states in their decision-making processes. The Second Session of the IUCN World Conservation Congress (Wiseman and Hopkins 2001) again promoted the sustainable use of WL as a way of protecting biodiversity and supporting the development of rural communities (Jeffers et al. 2015). Generally, it is the maintenance of high levels of biodiversity that guarantee the conservation of natural faunal balances, which entails the conservation or the reconstitution of adequate faunistic biodiversity values at subspecific levels as well (Hawksworth and Bull 2007; Zunino and Zullini 2004).

If the case is restricted to a group of species or just to a species, it is very different in the case of the large carnivores, or, e.g., the Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) , because their protection implies the preservation of an entire ecosystem (Quammen 2003). However, in the case of the threatened subspecies of the red deer (Cervus elaphus) , it does not mean that the natural ecosystem is preserved, but only the “ecological-managerial” aspects that are favorable for their continued survival.

Conserving species at the top of the food chain (key species) or focal species in a broader sense is the norm for the conservation of an ecosystem, but it must also be said that there are hybrid situations such as that of the case of the brown bear (Ursus arctos) in Romania (Quammen 2003; Stringham 1989), which is widely “artificially fed” and yet “preserved,” even at the expense of naturalness. In a certain sense, even the provision of carrion dumps for scavengers (e.g., griffon vulture, Gyps fulvus) falls into this category. This certainly applies to all endangered species that, in any case, take advantage of environmental transformations triggered by human activity.

I would therefore propose to distinguish three forms of WLC:

-

1.

Type A conservation of all the “natural balances,” implying a great limitation of human activities.

-

2.

Type B conservation versus a partial naturalness and enabled by substantial human-engineered assistance: e.g., Ursus arctos, Gyps fulvus, etc.

-

3.

Type C includes species at the base of the food chain including Cervus sp. and mountain sheep Ovis spp., namely, species which may be a priority – although this is not always the case – and involves only certain interventions such as their reintroduction or the imposing of limitations on their harvesting, etc.

A paradox is that the conservation of type C may require the control of key species in terms of conservation of the type A. A case of this kind took place, for example, in the National Park of Abruzzo, Lazio, and Molise (Italy) with the hypothesis of reintroducing the lynx (Lynx lynx) (whose autochthony was in any case questionable) where, however, the Apennine chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica ornata) might be threatened, when at that time there were less than 500 individuals of this endemic threatened subspecies.

Hunting can make a contribution to reintroduction of the huntable species (Perco 1997) as well as to the control of problematic species such as wild boar (Meriggi et al. 2016; Perco 2017), red deer (Ferretti et al. 2015; Perco et al. 2001), elephant (Le Bel et al. 2016; Schloles and Smart 2008; Slotow et al. 2008), and IAS (Dahl et al. 2000).

However, WL can be managed from a range of perspectives and with different purposes (Di Minin et al. 2013b), dependent on the context and the institution charged with their management.

The management of the WL in a protected area is different from that to be conducted in an urban setting or on a hunting reserve. Not only according to the institutional context but also to the stakeholders (Varner 1998), the geographical area, the dominant culture, and the historical period (Buijs et al. 2009; Giles 1978; Gossow 1983; Leopold 1949; ISPRA 2011; Kiss 1990; Mace et al. 2012; Saunders 2013). In short, the management of WL can respond to the following priority purposes: protection, hunting, economy, research, leisure, observation, sensitivity training, or ideal or ethical values (Bookbinder et al. 1998; Perco 1997; Reimoser 2018b; Ripple 2016; Ulrich 1983; Williams et al. 2000). Each of these purposes has the obligation to preserve and guarantee the satisfaction of the ES.

3 Coexistence

As previously mentioned, all management aims should allow, or rather consolidate, the conservation of the species managed while taking into account the priorities.

In a hunting area, the priority is the game bag, but without threatening the protected species. In some speciale cases, such as the conservation of the gray wolf outside a protected area, we cannot ignore the interests of farmers (economic option, Mech 2017). Naturally all this requires careful balancing and a positive relationship with stakeholders (Giles 1978; Kiss 1990; Leader-Williams and Hutton 2005).

Coexisting means “existing together,” at the same time, or in the same place without regard to the differences. Therefore, coexisting does not imply active conservation.

The crux of the matter of compatibility (coexistence) between hunting and conservation must be tackled in two respects: when hunting is inherently incompatible with conservation or if its compatibility depends on how it is carried out.

It is compatible if it is carried out “correctly”; it is not if it is carried out in an inappropriate fashion. The problem must be faced in an objective manner, regardless of ideologies. If there are cases in which hunting preserves biodiversity, irrespective of the number of cases and the difficulties that exist, this means that it is compatible with conservation.

4 Types of Coexistence

We can distinguish four types of coexistence between hunting and WLC:

-

1.

Non-impactful Hunting (NIH). These are hunts that are not “impactful”; that is, the harvesting and related activities (disturbance) are minimal and without significant or permanent consequences for the resource.

-

2.

Impactful and Eliminatory Hunting (IEH). This hunting is both impactful and “eliminatory.” An example of this kind includes the megafauna of the Pleistocene (outside Africa) which was destroyed by Homo sapiens. This type of hunting exists also today, e.g., Steller’s sea cow Hydrodamalis gigas (1768+), the passenger pigeon Ectopistes migratorius (1914+) and the Tasmanian tiger Thylacinus cynocephalus (1936+), etc.

-

3.

Impactful but Resilient Hunting (IRH). This hunting is impactful but WL exhibits “resilience” (the capacity of the resource to recover from exploitation), restoring its losses (quantity, structure, other characteristics) over variable timescales.

-

4.

Impactful but Contributory Hunting (ICH). This hunting, although impactful, brings some advantages to the WLC in question.

5 Non-impactful Hunting (NIH) and Its Effects on Conservation

Neglecting a logical but only theoretical discourse with regard to the number of hunters (ten hunters in the USA would be non-impactful) (but see also Martin 1984: 367, in Martin and Klein 1984) involves forms of hunting that could be termed “primitive” (i.e., “natural” or “native”) and therefore very different from modern ones, with firearms.

These “primitive” hunts, for survival or subsistence, can be distinguished by their great variety of forms.

They may be practiced without tools (e.g., collecting eggs, capturing nestlings or juvenile and injured individuals) or with tools of various types including poisons, intoxicants or adhesive substances (birdlime), snares, nets, traps, leghold traps, and up to bladed weapons, bows and arrows, or spears.

Today this type of hunting is part of indigenous peoples’ traditional livelihood, not yet under the influence by so-called “civilization,” and could be considered marginal as they are still used only by the few surviving tribes and groups of natives (in the Amazon Forest and the Fayu in New Guinea), Pygmies, Khoe-San, Inuit, indigenous Australians, etc. Despite this, they are not at all unknown in developed countries, as they are part of the illegal methods of hunting (poaching).

Traditional hunts are involuntarily conservative depending on the abundance of prey, the ability to obtain them, the presence of alternative prey, and the lack of technology and hunting techniques.

Therefore, the level of awareness is generally absent, as it is linked to necessity and the fauna is seen as an endless resource (Corlett 2007; Duda 2017; Festa-Bianchet et al. 2011; Gunn 1994; Harrison et al. 2016).

This does not mean that there is or there has been a certain awareness that the resource should not be exhausted, in order to be able to use it again, but this only occurs when it is not subordinate to immediate requirements. In regards to the rules governing primitive hunting, this is not a question about true norms but involves shared rituals. These are not infrequently more compulsory than written rules. This said, regulated hunting activities are, par excellence, the only ones able to achieve a certain level of compatibility, not least because they are subject to modification as a result of an improvement in knowledge, awareness, and sensitivity.

A distinction must be made between survival hunting and subsistence hunting. The latter is necessary to live (Cahill 1998), while the former is an exclusive activity in which Homo sapiens has no resource other than hunting and/or harvesting.

Survival hunting exists beside other productive activities, such as agriculture and livestock rearing. Subsistence hunting implies a minimum level of resources which is constant albeit extremely poor, while in the survival hunting, the hunted resource is the only resource available for survival (Donaldson 1988; Harrington 1981; Kenny et al. 2018; Kobayashi Issenman 1997). Subsistence hunting may in fact represent a prelude to a hunting economy (Peres et al. 2006; Vizina and Kobei 2017), passing through a phase of sustainable subsistence hunting, that is to say hunting which slowly ceases to be a forced requirement and then able to plan the exploitation of animal resources.

This also occurs because agriculture and livestock rearing bring about a change in thinking; in fact both are based on a certain level of planning and forethought, a sense of saving (of seeds, food, and breeding stock) and, therefore, of a “forward-looking” use of the resource. A change with regard to the awareness of traditional hunting is made difficult, by the weight of lore and the related rituals which conflict with the need to change, even in the case of excessive withdrawals and environmental and climate change. Culture and tradition are a powerful curb on change and not only in this field.

Changing a traditional hunt with deep cultural roots related to the economy is a very difficult job (e.g., the poaching of European honey buzzard, Pernis apivorus, in Calabria (Italy) (Agostini et al. 1999). It is simpler to prohibit it, at least apparently, but there is a risk of a profound resistance including revenge poaching. When hunting takes advantage of modern technologies (e.g., seal hunting with carbines by the Inuit), violations are not only the norm but take on an even greater danger for the resource in question. Some ancient hunts are strongly ritualized and inserted into a popular or noble tradition and have been progressively emptied of their cruelest aspects (e.g., foxhunting on horseback or the Gran Venerié with hounds used for hunting red deer or the falconry, etc.; Poplin 1987, Dickson et al. 2009).

To a greater or lesser extent all these forms of hunting possess an entertainment element, cultural ritualization, a sense of belonging, and physical exercise but their contribution to conservation, however, is lacking.

In conclusion, if they do, survival and subsistence hunting preserve only involuntarily, regardless of whether they are ritualized, cultural, or not.

6 Hunting That Is Both Impactful and Eliminatory: Impactful and Eliminatory Hunting (IEH)

All “primitive” populations (Martin 1984; Diamond 1999, 2006) have destroyed many species of mammals and birds who were not used to the presence of the humankind. The only populations of megafaunal communities to have escaped this extinction are those that have coevolved with early humans (in Africa and perhaps part of Asia, according to Martin 1984 and Diamond 2006).

But even in very recent times many other species have been brought to extinction by hunting. It is also true that in these cases other causes have often contributed and that in some cases hunting has proved to be less important than in others. Environmental destruction, the domestication of the species (the aurochs, Bos primigenius, and the tarpan, Equus ferus ferus; Hainard 1949) with economic or social and cultural needs, are the main causes of disappearance, but it must be said that hunting has often dealt the coup de grace. Today, however, it seems that hunting is almost irrelevant while other causes appear much more important, except in cases where hunting is closely connected with economic needs such as the Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica) (Quammen 2003) or cultural one such as a status symbol (horns of black rhinoceros).

7 Impactful but Resilient Hunting (IRH)

Hunts of this kind allow a certain increase or a natural change in the ecosystem but it is necessary to distinguish two separate scenarios: (1) unaware (unaware conservation, UC) due to a lack of technology or the extent of pressure and (2) aware (aware conservation, AC) for different reasons which will be examined. UC is typically involuntary but may have lasting effects which can also be positive even from a psychological perspective, in the sense that it may end up motivating individuals or human groups who are interested in continuing to hunt noninvasively (though their reasons may vary) and they therefore undertake a range of actions, the simplest of these being to exclude other subjects from harvesting the resource and to therefore operate a sort of surveillance that may be informal or even professional.

In addition to these activities, which are the simplest and the most common, there may be others concerning the environment, its general management, and that of other species that ranges from monitoring to control. In short, and not without reserve and caution, this represents a passage from an unconscious “conservative” hunting to a conscious and programmed one, but with the warning that in many cases the objective is partial and specific (i.e., red deer, Cervus elaphus) and which therefore entails the elimination of species perceived as detrimental (e.g., gray wolf, Canis lupus).

However, the conservation of one species to the detriment of another is not real conservation.

It is worth pointing out that this culling is not hunting but represents a set of actions aimed at eliminating the (from a human perspective) “harmful” effects of an animal population (Scholes and Smart 2008). Professionals or even volunteers may carry out the control, but the merely recreational part of the hunting is absent or reduced, even if it may also be present in some forms, especially when someone is volunteering. The control itself aims at efficiency and effectiveness while the hunting is aimed at personal satisfaction. When hunting is mainly for direct economic purposes (the production of consumable meat) it becomes close to control. A very clear difference, however, does not seem to exist; in fact there are several intermediate forms, especially because of the operator’s subjectivity, and a good definition should be based on the extremes, in this case entertainment versus the elimination of damage.

Regulated hunts have at least one common basic idea: the protection of some species or their non-extinction, which does not mean they represent the same thing. Professionals (e.g., wildlife managers, WM) and hunters themselves therefore distinguish between hunts that are “well carried out” from those that are not (Fukuda et al. 2011).

In ancient times, with the beginning of agriculture and animal husbandry, the first Homo sapiens felt the need to furnish themselves with rules either because hunting was reserved for powerful people (and they reserved it for themselves through severe punishments) or because, in hunting, those rules of prescient use were applied, having been borrowed from their own agro-zootechnical practices and obviously dependent on the various cultures and requirements. Hunting was a male activity representing virility training and might have been preparatory for war as well as representing a sphere of freedom and therefore one with as few rules as possible. According to its virile and warlike rules, hunting was more important the more a trophy was coveted and dangerous. Hence the interest of the ruling classes (rulers) as a symbol of their powerful status, but even in a such context hunting, although reserved for a select few, did not coexist with conservation. This said, sometimes in Europe single species were preserved from massive harvesting and humankind witnessed the enactment of edicts, true and proper regulations, aimed at ensuring that hunting could still continue.

Since hunts using poor technology coexist quite well with conservation, it is worth remembering a tendency, particularly prevalent in the United States, to voluntarily renounce certain advantages that the hunter has over the prey which includes hunting with muzzle-loading rifles and bowhunting, equipment that, in fact, requires much more skill on the part of the hunter and in some ways gives more chance for the prey to escape (see Case Study 3 - Oregon).

8 Special Situations Involving IRH

In Europe, particularly in countries that make reference to a Central European tradition, hunting has a managerial character that is explained by the phrase “Jagd ist Hege” (Hunting is management) (Silva-Tarouca 1927, in Raesfeld 1958). The meaning is that hunting is an “entertainment” economy and part of the overall management of natural resources, in which the forest (and forestry) plays the major role. In this sense, the hunter does not simply buy a permit (as in the USA) and neither is he interested above all in the result (as an expression of great skill), but believes he has obtained the prey because, in a sense, he has taken care of it, “loving it” (Hegen in German, Reimoser 2001 and 2018a).

This approach directly involves the hunter – often only the owner of the hunting rights – in the entire set of management activities including censuses, environmental interventions, etc., and is particularly the case in German-speaking countries and surrounding areas (Linder 1978). It has profoundly influenced an attitude toward all the activities connected with hunting, starting with cynophilia.

An approach of this kind is very important in cultural terms and represents a subjective attitude toward nature (with some deviations, which we will address later). We can distinguish three types of approach to hunting. These are the hunter (venator) dominus, the venator socius, and the venator emptor.

The venator dominus is the one that directly manages and organizes hunting because the law allows him to exclude other subjects. Generally, he is the landowner or the owner of the hunting rights and runs and/or rules them alone or at most with a few other colleagues, friends, or relatives, never more than 3–5 people with a range of responsibilities. The list of hunts of this type covers the royal and noble hunts (Howe 1981; Ortega y Gasset 1972) to those of landowners or even owners in consortium, a formal association of contiguous landowners operating as a single unit (such as the private reserves, cotos in Spain, etc.).

The venator socius is associated, i.e., registered, to a specific district and hunts along with others in an ongoing enterprise (with social hunting objectives) and pays a periodic fee, usually annual. Depending on personal inclination, time constraints, and individual resources, he (for he is usually but not exclusively male) is involved to a greater or lesser extent in the management, but the situation is not always obvious. The contexts greatly vary at the global level and it ranges from associates who know each other (with a maximum of about 40 individuals involved), this is because the objective is restricted, and therefore a certain degree of self-regulation is facilitated, to other cases in which the members barely know each other at all, because they hunt on areas covering tens of thousands of hectares.

A smaller number of members still allows for some sort of self-management. Naturally this is a matter that applies to a group of hunters who are known to each other, often living close to one another and who share language, family ties, and social relationships and a context in which social control, very strict and personal, is particularly effective (Dunbar 2004, 2010).

The venator emptor often hunts abroad or in any case far from his place of residence, buying hunting rights from time to time, thus investing large amounts of money. This category fits very well with the category of trophy hunters (Gunn 2001).

There are also mixed approaches in which venatores domini are often also emptores, mainly because they can afford to, while socii are more rarely emptores or in some cases – and not in Europe – are associated de facto; in other words they are forced to hunt in a given territory for a range of circumstances, generally due to financial constraints or other types of necessities.

NIH-type hunts can evolve positively toward impactful contributory ones (ICH), even though the opposite is also often the case, with the degradation of an ICH toward a “flat” coexistence with conservation, of a passive type. For example, sometimes the Central European hunters tend to see gray wolves and/or lynx as an obstacle to good management results (Treves 2009).

A particular case is that of trophy hunting (TH). TH implies the hunt of animals with specific characteristics which can be stored as a memento of the adventure including antlers, horns, tusks, skulls, skins, or even the entire stuffed specimen. The characteristics of these trophies have been codified internationally, initially with the “Records of Big Game” (1895), then with the “Records of North American Big Game” (1932), and, finally, with the rules of the Conseil International de la Chasse, CIC (1934), currently still in force and which unify the Anglo-Saxon, North American, and European systems.

This kind of revolution (definable, because TH establishes the quality of trophies with objective criteria, which allow for a comparison between them) was made possible by the progress of war and hunting weapons in the late nineteenth century (smokeless gunpowders, progressive and special optics), which allowed the adoption of sniper rifles.

Unlike the Anglo-Saxon/North American school, the Mitteleuropean school has made its “livestock” its flag (Raesfeld 1957; Ückermann 1952) being based, at least at the beginning, on concepts derived directly from animal husbandry and more precisely on the idea that it is possible to improve the quality of a species (from a trophy perspective) by eliminating subjects with undesirable characteristics. Basically, a sort of special selection, so much so that some authors had adopted the slogan of “breeding with the rifle” (Rehwildhege mit der Büchse – Roe Deer Management with the rifle – Wagenknecht 1976). This criterion was called into question after 1960 (Bubenik 1970; Elsmann 1971; Hennig 1961; Jelinek 1989; Kurt 1991; Stubbe and Passarge 1979) but especially post-2000 (Apollonio et al. 2010) and at present is considered non realiable.

Nowadays, with the new opportunities for mobility, TH has assumed global dimensions. With reference to the following chapter (impactful contributory hunts, ICH) and above all to an extra-European examine, it can be argued that this form of hunting can be considered compatible on condition that some essential biological rules are respected:

-

The harvesting of endowed subjects takes place in very low percentages, thus avoiding affecting the average quality of the population (Perco 2014).

-

The avoidance of harvesting during the mating season and before.

-

Harvesting even during the mating season but only a modest fraction of the qualitatively important subjects.

-

Harvesting only very old subjects at the end of their reproductive careers. This is a case of sound (biological) effectiveness for Bovidae but not practicable for Cervidae.

It should however be remembered that rare species (and subspecies) should be managed with particular caution. The trophies of rare species or subspecies have a greater value than the most common ones and this could encourage excessive harvesting (Palazy et al. 2012).

9 Impactful but Contributory Hunting (ICH)

We now address the positive contribution of ICH to conservation and for which it is possible to make a distinction depending on the fields of intervention and the modalities for which there is conservation or not. WL is preserved, more precisely:

By interventions on wildlife:

-

1.

Reintroductions

-

2.

Control

-

3.

Eradication

By environmental improvements:

-

1.

Habitat restoration or habitat maintenance

-

2.

Supplementary feeding

By interventions on (local) communities:

-

1.

Through the activation of anti-poaching surveillance

-

2.

Through monitoring

-

3.

Through the improvement of the social conditions of local residents

-

4.

Through an improvement in the attitude toward wildlife (nonresidents)

10 Interventions on Wildlife

-

1.

Reintroductions

In this case, we mean the reintroduction of species that will be huntable in the future and for which the intervention is explicitly or at least indirectly done for this reason. Coexistence and awareness are high and so, obviously, these correspond to an effectiveness if the planning and operations have been carefully carried out. One risk is to make the community in question, of hunters, but not exclusively suspect that a reintroduction may serve as a pretext or opportunity to create a protected area with obvious consequences (including hunting prohibitions and limitations of various types). Therefore good communication is necessary.

-

2.

Control

By this term we mean the control of antagonistic species, excluding domestic ones (and not part of wildlife) in a numerical or structural sense. This may prove a very contradictory measure, as it is aimed at strengthening species that can be hunted to the detriment of other species and is generally quite effective, but the level of coexistence/awareness is very low, as it tends to label species as useful or harmful and is thus recommended only for “opportunist” and/or those of least concern (LC) including magpie (Pica pica) , crows (Corvus spp.) , and wild boar (Sus scrofa) or European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in certain contexts. However, the numerical reduction of some highly competitive species (Cervus elaphus, Loxodonta Africana, etc.) may also prove necessary or indispensable for environmental reasons (Perco 2001; Reimoser 2001, 2018b; Scholes and Smart 2008; Slotow et al. 2008). In reality there are quite a few species that, in certain contexts (environmental, social, etc.), can be considered “problematic” and that require a sort of control carried out, sometimes using lethal means (Angelici 2016).

-

3.

Eradication

The complete elimination of a species in a given area is necessary for IAS (Invasive alien species), such as coypu, Myocastor coypu, and gray squirrel, Sciurus carolinensis, in Europe. In very particular circumstances, eradication is also recommended for some native species (gray wolf, according to Mech 2017), when it comes to highly problematic species in very delicate socioeconomic or cultural contexts. In some cases, the collaboration of hunting organizations was essential for the success of project management (raccoon Procyon lotor, Dahl et al. 2000; muskrat Ondatra zibethicus, Gosling and Baker 1989).

11 Environmental Improvements

-

1.

Habitat Restoration or Habitat Maintenance

For example:

-

Advanced forestry management (high forest introduction, naturalistic cutting of coppice, extirpation of allochthonous species, thinning, etc.)

-

Restoration and care of natural meadows and pastures

-

Controlled fires

-

Care of wetlands (flooding, reed cutting, grazing, etc.)

-

Intentional and programmed abandonment of open areas

-

The level of coexistence/awareness is high but is directed toward certain (huntable) species even if it can indirectly favor many other species. The effects are positive.

-

-

2.

Supplementary Feeding

Wildlife crops. These are specific cultivations aimed at strengthening certain (huntable) species or reducing damage by the species in the nearby areas. The level of coexistence/awareness is good but oriented (see above) and the effectiveness is comparable with environmental improvements. A contraindication is that these interventions can sometimes increase certain species in an abnormal fashion.

Direct provision of food. This includes several food attractants in addition to water and salt or fodder treated with fragrant essences, etc. The resultant increase in huntable species (e.g., ungulates) has a clear purpose, with greater harvests in loco (Raesfeld 1958; Reimoser 2001). Initially, this was carried out for ungulates (in Europe), but now it involves many other species including ducks and geese (France, Italy, Argentina, etc.) and brown bear (Romania). In the case of ducks, it allows excessive and never-before-seen bags and leads to the culling of protected species (Boyd 1990; Perco Fa and Perco Fr 1992). Although it has clear management approaches, the level of coexistence/awareness is ambiguous or modest and the overall effects may be negative for conservation. Open-pit carrion dumps, fixed or movable, to attract carnivores or scavenging bird species, are useful when they are not associated with hunting, even if they have been subjected to severe criticisms in the case of certain mammals such as the grizzly subspecies of brown bear (Stringham 1989; Craighead 1998).

12 Interventions on the Local Community

-

1.

Activation of anti-poaching surveillance. This is mainly aimed at protecting huntable species but its effectiveness is nevertheless high because it concerns all species (Roe et al. 2017). The level of coexistence/awareness is very good with only one criticality to be suspected, or worse accused, of acting against the interests and/or traditions of local communities (Corry 2011, 2015). The effectiveness remains high.

-

2.

Performing monitoring. Unlike the previous intervention, this is effective only for the species monitored, therefore those being hunted, even if for these the level of coexistence/awareness is high. Indirectly it may also require monitoring other species but this is very unusual. One critical aspect is that if it is not carried out with the collaboration of local stakeholders, then their interest (see also the following points) in the conservation of the resource will decline. The case described applies to venator emptor and not for members who put themselves forward to carry out the monitoring, which is not always in a reliable fashion if they are not supported and/or organized by professional technicians. The case of venator domini is different because it can be convenient to involve local actors, on large areas; but this situation is very rare in Europe and elsewhere; it only applies if the dominus is represented by large landowners (Africa) or institutions (governmental and not) (M. Fabris pers. comm. 2018). Anyway, a minimum and essential level of monitoring is generally a duty for all states (Selier and Di Minin 2015).

-

3.

Improvement of Residents’ Social Conditions

Economic improvements. These can be divided into three categories: compensation or reimbursement for damage, income integration, and targeted improvements in traditional productive activities (agriculture and livestock rearing). Furthermore, to the extent that the natural capital has been retained, payments for ecosystem services ensure benefits and well-being.

(http://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/research/newsalert/pdf/30si_en.pdf)

Compensation or reimbursement. Compensation presupposes responsibility while reimbursement represents only a pro bono pacis contribution, but not always, according to rates and/or appraisals. Without going into the context of the various very different disputes which depend on the juridical regime of the matter and the “ownership” of wildlife, it should be noted that the level of coexistence/awareness is modest or absent and the efficacy is rarely appreciable as the person who has suffered damage feels underestimated and generally cheated with regard to the size, promptness, and the method of compensation. These are procedures to be used only when there is a lack of better initiatives, as they do not create “alliances.” In addition, wildlife is always perceived as damage and “it would be better if it wasn’t there.”

Income integration. This is such only if it takes place before any incidents or requests and could almost be considered a type of rent paid in advance to local communities. The level of coexistence/awareness, always meaning from those paying it (the venatores), is average or even good but everything depends upon the way in which it is paid. An appreciable personal relationship between the parties can at least be established, but often it is only provided for the purpose of “keeping them quiet” so that they do not demand subsequent compensation. In theory it is an effective method but it depends very much on the venator’s ability to establish a relationship with the potentially damaged parties (Nguinguiri et al. 2017).

Targeted improvements in traditional productive activities (agriculture and livestock rearing). These are by far the best in creating coexistence/awareness on both sides and are also highly effective in establishing good relationships, the key being to make people understand that wildlife is a resource that helps the local community if certain rules are followed. A problem, and not a small one, is balancing agriculture and/or animal rearing with wilderness or naturalness, because if we support additional activities (see over) they can, merely by their spread, jeopardize the very conservation they sought to obtain, and this process can therefore be a double-edged sword.

-

4.

Cultural Improvements

These include the improvement of education and culture and therefore also knowledge about wildlife as a resource. This is an excellent way to obtain good results in the future and the degree of coexistence/awareness is definitely high. In one way it accomplishes the improvement in social conditions and the life of local communities and represents a particularly effective and long-term solution if individuals deal with problems, related to education, integration, gender equality, and demography, that is to say with respect for culture and local sensibilities. One risk, which is not unimportant, may prove to be a possible (probable) increase in the local population with obvious consequences on conservation. It is true that a greater number of residents aware of the economic and cultural value of wildlife is much better than the opposite, but nevertheless there are limits to man-made density beyond necessity, which may mean the disappearance and/or the reduction in biodiversity that we were seeking to protect. It is therefore similar to the previous case (that of economic improvements) of a poorly managed instrument that may become a double-edged sword. At least theoretically, cultural improvements are more effective even over the long term than economic ones, which may lead, in not a few marginal situations, to phenomena of hoarding and exploitation, where reliable public authorities and/or effective social controls are lacking (Bocci 2011; Di Minin et al. 2015; Leader-Williams and Hutton 2005).

13 Creating an Improvement in the Approach to Fauna (Nonresidents)

Tourism, or, even better, aware tourism, can reduce the use of wildlife through hunting when it is carried out in the same areas. Nevertheless, mixed uses of wildlife should not be ruled out (tourism, especially but not only photographic tourism and hunting, etc.) for which there may be a temporal or (partial) geographical displacement of the two activities. The first consists of a type of tourism outside the hunting season, while the second one includes protected areas on the edge of areas used for hunting. These are possible and manageable hypotheses even for hunting managers and for this reason we mention that for iconic species (especially in Africa) tourism requires, however, “[…] political stability, proximity to good transport links, minimal disease risks, high density wildlife populations to guarantee viewing, scenic landscapes, high-capital investment, infrastructure (hotels, food and water supply, waste management), and local skills and capacity” (IUCN 2016: 8), and this creates many difficulties, even if they may be considered highly complementary activities. Wetlands and areas suitable for ungulates may play an effective role by allowing the use in part of the structures planned for hunting as observation points, during moratoria periods. The difficulties involved in these compromises should not be underestimated as the tourists’ approach is generally contrary to hunting and to the hunters themselves although their organizations (tourism, bird-watching, etc.) prefer not to come to terms with the hunting associations. However, these are possibilities that should be explored with the aim of increasing mutual awareness and tolerance, combined with sound knowledge; moreover, there are some educational projects to be borne in mind to at least explore.

14 The Problem of Trophy Hunting Especially for the Venator Emptor

Trophy hunting is a recent development around the middle of the twentieth century, so well after the invention of the “rifle.” Hemingway (1935) in North America and Raesfeld (1958) in Europe mention it in their writings.

Trophy hunting is based on choice and is therefore typically selective, using the excellent optical instruments available. Certainly its subjective motivations are the proof of great skill or luck, a symbol of status which is nice to share with a few friends and some enthusiasts, albeit in a very personal way.

The search for the most “beautiful” or greatest value trophy, following a score validated by an international commission, the CIC, is constant. Local and world exhibitions of trophies are important events for the experts in the subject and may represent real competitions with a slightly sporty flavor, even if hunting is not a sport in the proper sense.

Only a fraction, 10–20%, according to T. Terzi (2018) (pers. comm.), of world hunters are interested in trophy hunting. Therefore, they vary between 5.7 and 11.3 million. It is believed that the percentage of hunters in the EU is 20–25% higher than this total, namely, around 1.3 million (a personal estimate). A significant part of these (more than 60%) mainly hunt in their own country (Table 8.1).

TH has often been criticized, especially recently, when a beloved lion named Cecil was killed by an American dentist in Zimbabwe (2015), sparking fierce criticism from animal rights groups and fueling a backlash that set social media ablaze with condemnation and death threats. Criticisms are of different kinds: technical, economic, social, and ethical (Aryal et al. 2015; Buckley et al. 2015; Cohen 2014; Coltman et al. 2003; Crosmary et al. 2015a, b; Dahles 1993; Di Minin et al. 2016; Festa-Bianchet et al. 2014; Kaltenborn et al. 2013; Kurt 1991; Leader-Williams et al. 2005; Lindberg et al. 2003; Lindsey et al. 2005, 2006, 2007a, b, 2012; Mysterud 2011; Nelson et al. 2013; Norton 1984; Palazy et al. 2012; Ripple et al. 2016; Treves 2009).

In particular, they are critical of the following elements:

-

From a technical point of view, the excessive numbers culled, the culling of subjects at the peak of their reproductive powers, the destructuring and disturbance when widespread (e.g., in Europe), the vulnerability of certain species, the absence of specific studies, and the fact that there are no forecasts looking at consequences on the ecosystem.

-

From an economic point of view, the distribution of profits, the absence, or the low sums destined for reinvestment in conservation projects, while it is suggested that aware ecotourism may be an alternative option.

-

From a social point of view, corruption and/or political instability, the possibility of circumventing the rules, the scarcity of controls, and the charismatic value of some species. It is also assumed that TH is a boost to poaching.

-

From an ethical point of view, the existence of animal rights, hunting versus canned animals, the fact that TH is elitist and/or confirming a certain white supremacy, and an indicator of colonialism. Corry (2015) supports the notion that even the parks in the USA are a colonial construct, a judgment that is certainly exaggerated.

The criticism of TH from this perspective is often a condemnation of hunting in general, sometimes from very particular points of view (ecofeminism: Kheel 1996) with nods toward anthropology and traditions (Howe 1981), to the relationship with the landscape and prey (Reis 2009) and to respect for the prey (Taylor Ang 1996): “There are circumstances in which the killing of a human being may be justified, but to mount this person’s head on a wall is not usually [!] considered acceptable.”

Remaining with the point of view of ethics, Gunn states (2001): “I assume animals have interests, and that we have an obligation to take some account of those interests: roughly, that we are entitled to kill animals only in order to promote or protect some nontrivial human interest and where no reasonable alternative strategy is available.”

Others however consider the hunt from the moral point of view (Causey 1989; Loftin 1984, 1988; Leopold 1949; Ortega y Gasset 1972; Shepherd 1973; Taylor Ant 2004, 2009; Vitali 1990) with greater or lesser intensity.

Cohen (2014), again quoting Gunn (2001) argues that: “None of the Gesinnungsethik (Weber 1919) approaches, is completely consequential in its prioritization of animal life; all concede that hunting animals might become ethically permissible under certain circumstances…The Verantworungtsethik (again Weber 1919) representatives [on the other hand] of an environmental ethics in fact sought to define these circumstances.”

Apart from the problem of the morality of hunting, it should be noted that the definition of TH (according to Gunn 2001, Cohen 2014, and others already quoted) is rather reductive and incomplete. In them, they tend to believe that the motivations of the trophy hunters (THs) are all the same or very similar and therefore formulate a condemnation or especially ethical perplexity, based on the concept that people conducting TH are very rich people who pay just to kill for fun or who enjoy killing defenseless/innocent animals. THs would mostly be shooters, within game parks or farms, but if we analyze the phenomenon it is not so because THs include a lot of domestic hunters (both in the USA, in Canada, and in Europe). But the relative appreciation of the aforementioned authors for the sport’s hunter that implements a kind (kind of) “fair chase” with the prey is also very debatable and even negative, at least for the hunter-manager of the Mitteleuropean school (Bubenik 1984; Elsmann 1971), that is to say the hunters who are directly involved in the management of their own hunting (see over, Raesfeld 1958).

Above all for the ethical reasons mentioned above, the proposals include its replacement with ecotourism, strong restrictions or a total ban, and a ban on the import of trophies (a request of some members of the European Parliament to the EU, 2016).

Other authors are much more drastic (Harrison et al. 2007). In addition Corlett (2007) says: “Over the last 50 yr, the importance of hunting for subsistence has been increasingly outweighed by hunting for the market. The hunted biomass is dominated by the same species as before, sold mostly for local consumption, but numerous additional species are targeted for the colossal regional trade in wild animals and their parts for food, medicines, raw materials, and pets. …. Most of this hunting is now illegal, but the law enforcement is generally weak. However, examples of successful enforcement show that hunting impacts can be greatly reduced where there is sufficient political will. Ending the trade in wild animals and their parts should have the highest regional conservation priority.” But their findings concern Asia and suggest rather a hunting moratoria and/or systems which are more aware.

Technical, economic, and, in part, social criticisms are generally accepted, but the overwhelming majority of authors above quoted, and technicians claimed, that these faults do not cancel out the usefulness of TH.

In particular, in 2016 the International Union for Conservation of Nature issued a document entitled “Informing decisions on Trophy Hunting. A Briefing Paper for European Union Decision-makers regarding potential plans for the restriction of imports of hunting trophies,” which highlights the substantial opportunity of TH.

-

Not only the IUCN (2016) but other authors as well (Cooney et al. 2017; Di Minin et al. 2013a, 2016; Festa-Bianchet 2017; Leader-Williams and Hutton 2005; Leader-Williams et al. 2005; Lindsey et al. 2006, 2012; Roe et al. 2017; Webb et al. 2004) argue that, even if there are unpleasant situations, there are also several reasons to support a coexistence with, and indeed the usefulness of, TH, including that:

-

A total ban would see important financial resources lost (at all).

-

These resources are indispensable for conservation and for the fight against poaching (Roe et al. 2017).

-

The resources, taken out the operators’ remuneration, generally go 50% to the local communities and for the rest to the government agencies (in Namibia 90% goes to the local communities, IUCN 2016).

-

The resources are fundamental in order to help local communities understand that it is worth to preserve wildlife through reintroduction projects (Makombe 1993; Webb et al. 2004).

-

The resources are also in the form of “consumable meat” (bushmeat) and as such they are “essential” for populations living in total destitution (Kupiers et al. 2016; M. Pani pers. comm. 2018).

-

Ecotourism is not practicable everywhere, particularly for security reasons (Kiss 2004; IUCN 2016).

-

Ecotourism requires many investments (IUCN 2016) and “customers” would also be easy to please (Di Minin et al. 2013a; Goodwin and Leader-Williams 2000; Krüger 2005; Novelli et al. 2006).

-

Many hunters prefer poorly accessible areas and to enjoy the wilderness of these places (Lindsey et al. 2006).

-

TH (in Africa) has a lower ecological footprint than tourism (Di Minin et al. 2013a, 2016).

-

There are several cases in which TH has had positive effects on conservation (Kock 1996). The IUCN document (2016) cites ten case studies of TH having positive conservation and livelihood benefits: rhinos in South Africa and Namibia, argali in Mongolia, bighorn sheep Ovis canadensis in North America, private wildlife lands in Zimbabwe, communal conservancies in Namibia, markhor Capra falconeri and urial Ovis orientalis vignei in Pakistan, and markhor in Tajikistan. Moreover it has benefits to nontarget threatened species and revenues for government wildlife agencies, including for anti-poaching and polar bears in Canada (IUCN 2016).

-

Where there has been a total ban on hunting, the wildlife situation not only has not improved but has even worsened, even if the reasons for this vary (Western et al. 2009).

-

Interventions of similar importance are not feasible, on an ongoing and non-episodic basis (IUCN 2016).

-

There is no need to renounce these activities for reasons, above all the ethical ones, in exchange for proposals that are not feasible everywhere: it is not good to throw out the baby with the bathwater (Cooney et al. 2017).

15 Case Studies of Hunting Related to Positive or Critical Consequences to Conservation

15.1 Case Study 1 Italy

Italy covers an area of 302,073 km2, of which 23.2% is mountain, 41.6% is hill, 35.2% is intensely cultivated plains, and about 8.000 km2 of which is wetlands (ISPRA 2011). There are roughly 6,5 million inhabitants with a density of 200/km2, among the highest in the EU. Italy has a very high wildlife biodiversity. The area covered by hills and mountains is suitable for the ungulates with at least 20,000 roe deer present in lowland areas in various populations.

Ungulates have increased about 200-fold since 1945, for environmental reasons (abandonment of the uplands) and currently (2017) there are estimated to be almost 2 million animals (mostly roe deer and wild boar; see Perco 2014). There have been several reintroductions of roe deer, red deer, and chamois both in hunting areas and in protected areas (60%). The gray wolf and the brown bear (the latter in two subspecies) are estimated at about 2000 and 110 individuals, respectively. The hunters’ contribution to the management of ungulates is positive where the hunting is selective (about 75% of the territory occupied by roe deer) and negative or neutral elsewhere. Wild boar is hunted mainly through drives with several hounds. 85% of the territory is suitable for the species (Carnevali et al. 2009; Pedrotti et al. 2001; Perco 2014).

10.5% of the Italian territory is within protected areas (MATTM 2010), 7,2% in urban areas (ISPRA 2015), and 6,9% in other non-huntable areas (ISTAT 2007), while the huntable area covers about 222,800 sq. km (about 75% of the national surface area). Hunting is regulated at the national level by a framework law with regional application laws except in the regions and provinces with special status (5/20). Eighteen of the 20 Italian regions are divided into territorial hunting areas (THA), of a social nature and on a provincial basis (one or more per province), each of at least 1000 square kilometers, with an unlimited number of hunters. Trentino-Alto Adige (and the autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano: Flaim and Brugnoli pers. comm. 2018) and Friuli Venezia Giulia (100% of the territory: Colombi pers. comm. 2018) as well as other provinces in the Eastern Alpine area (four, part of their territory) instead have social hunting reserves on a municipal basis. Private hunting reserves occupy around 5% of the area in question.

In Italy, fauna is an “unavailable state resource” and the landowner cannot prevent hunting on the land he/she owns, an almost unique situation in Europe. There are 48 huntable species, 13 mammal species, and 35 bird species.

The 580,000 Italian hunters spend an average of USD 500 (€425)/year for membership fees, regional taxes, and national licenses. The figure, which is significant (USD 290 million/€255 million), goes into the general financial management of the regions and/or the state and it does not concern conservation.

In order to become a hunter, a regional examination is required, with a differentiated difficulty depending on the region in question. A special course and exam are compulsory for selective hunting. Most hunters form part of the group of “migratory hunters” who do not contribute directly to the maintenance of habitats, with some exceptions (but taking large hunting bags) in the private hunting reserves of the Venetian lagoon. Poaching on all species is very high (Merli et al. 2017; Perco and Forconi 2016) especially in central southern Italy, in Sicily and Sardinia, but also in other regions (birds). Annual estimates of hunted species as well as bags are not available. The largest hunting association (Italian Hunting Federation, FIDC, covering about 50% of the Italian hunters) is carrying out some wildlife research.

The current national hunting law does not oblige the carrying out of censuses or even annual management reports, a situation that is judged as outdated together with the absence of the owner’s consent for the use of their own land for hunting purposes.

In addition, due to the shortcomings of the law, we would therefore like to suggest that only in the province of Trento and in that of Bolzano does hunting coexist with conservation, owing to the specific managerial methods provided under their autonomous system. This is also the case but with some exceptions for several Alpine municipal hunting reserves. In just a few districts of Emilia Romagna and, very locally, in Tuscany, hunting does not seem to openly be in conflict with conservation itself. As a trend, hunting management would be deemed, at least, passable in the region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, the only region in which the closed number of hunters is established by law (7923 on 6724 sq. km, divided into 247 municipal hunting reserves).

15.2 Case Study 2 Hunting, Wetland Restoration, Game Conservancy

In North America (United States and Canada) “Ducks Unlimited” is very active (Boyd 1990). It collects and invests huge funds for the re-naturalization and restoration of wetlands. Ducks Unlimited is an association that has operated since 1937, mainly in North America (Canada, United States, and Mexico, but also in Australia, New Zealand, etc.) particularly in the field of wetland restoration and reactivation.

It collects funds not only from its members (over 1000,000) but also through donations and research activities of various kinds. Since its foundation it has contributed to the re-naturalization of about 14 million acres (more than 5.6 million ha.) for waterfowl in general. An important component of DU is represented by hunters, as well as breeders of Anatidae, birdwatchers, etc. Again in the USA important re-naturalization work has been carried out by the army, some quite close to New York and elsewhere and covering thousands of hectares.

The Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust is a similar organization, founded in 1946 by Peter Scott under the name of the Severn Wildfowl Trust, which currently runs several wetland centers in the UK and promotes the field of protection and restoration of wetlands and its associated fauna worldwide. The strategy of conservation followed in this case is based on hunting areas or full protection, extended as a fragmented patchwork which represents the only truly effective model for the management of migratory or wintering waterbirds that are also game species. In this case hunters have also been, and still are, an active component of the organization since its inception (Lampio 1974, 1982).

Wetlands International (WI, formerly the International Waterfowl Research Bureau) is the most internationally active European organization in the field of research with projects aimed at conserving and increasing biodiversity, organizing technical meetings and conferences, etc. WI provides consultancy to wetland managers, including state offices as well as within the framework of the International Convention of Ramsar and the European Natura 2000 regulations (which do not exclude hunting).

Furthermore, other organizations of this kind exist at the international level. In Europe, but not only, hunting is often carried out on properties managed by private individuals. Therefore, many wildlife management organizations provide advice, even if they use state funds to some extent. For example “ICONA” (Instituto Nacional por la Conservation de la Naturaleza) in Spain is an important example where individuals deal with all kinds of wildlife. Similar institutions and organizations, with similar aims and to a large extent financed by private individuals, exist in other European countries, for example, in France, Germany, Austria, and Italy.

Particular attention should be paid to the large areas falling within the wetland areas of the Upper Adriatic and similar “private game reserves” elsewhere in Italy, where the owners of fishing valleys have largely moved from fish production to hiring out annual hunting pegs as a more profitable enterprise (USD 62,000, €50,000, or even more for the rent of a barrel per year). These initiatives are based on massive feeding programs and allow game bags sometimes numbering more than 200 ducks per day (Perco Fa pers. comm. 2018).

Since there is no real control, even on the killing of protected species or on the use of nontoxic ammunition (not containing lead), these activities are largely incompatible with conservation (Perco Fa and Perco Fr 1992).

In the case of huge game bags, in fact, the degree of involvement of the hunting world seems ambiguous, because although it is true that in the past there were significant efforts to preserve wetlands in the most suitable environmental conditions for hosting the typical fauna, in the rented or privately owned areas, today there is a growing tendency to favor intensive winter feeding of game species (Anatidae) to facilitate huge individual daily game bags. This tendency increases the habit of considering migratory or wintering wildlife essentially as moving targets for entertainment shooting (Bell and Owen 1990; Bregnballe and Madsen 2004; Fox and Madsen 1997). A remedial or mitigation action must be found in line with international experiences, with the establishment or maintenance of large areas of tranquility, reducing intensive winter feeding and increasing controls. The recent use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to police these areas in the Po Delta is an interesting development in this respect.

Again based in Great Britain, but with important initiatives at the international level, we should finally cite and appropriately highlight the activity of the “Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust” (formerly the “Game Conservancy”), an authoritative organization that operates in various sectors especially (though not exclusively) involving small game of interest for hunting by tradition and with economic implications, especially through interventions in agriculture, both in relation to wetlands and in cultivated or uncultivated areas (Keddy 2010; Tamisier 1985).

15.3 Case Study 3 Oregon (USA)

Oregon is one of the 50 states (in addition to the federal district of Washington) that make up the United States. It is on the west coast and it covers 255,000 square kilometers with about 4 million inhabitants (15.5/q km).

It is one of the states with the greatest environmental diversity, that is to say volcanoes, abundant water bodies, dense evergreen and mixed forests, as well as high deserts and semiarid shrub lands.

The “big game” hunting fauna consists of wapiti Cervus canadensis (two subspecies), three species of deer (Odocoileus spp.), black bear Ursus americanus, pronghorn Antilocapra americana, mountain goat Oreamnos americanus, bighorn sheep (two subspecies), and puma Puma concolor. Game bird hunting includes a variety of Anseriformes (ducks and geese) and upland birds such as wild turkey Meleagris gallopavo (two subspecies), grouse (six species), quail (two species), pheasant Phasianus colchicus, gray partridge Perdix perdix, and chukar Alectoris chukar, these last three being introduced.

Hunting is managed by a state agency, the Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), which oversees all aspects of wildlife hunting and research. The decision-making and executive power is a matter for a commission, the Fish and Wildlife Commission, composed of seven members appointed by the governor of the state which determines hunting, regulations, fees, and license costs, the latter diversified by age (veteran, senior, junior, etc.). The enforcement of rules and regulations is ensured by a special section of the Oregon State Police – assisted locally, when necessary, by other agencies.

The US federal agencies have jurisdiction only on the lands for which they are responsible. In the case of many Western states (Oregon, Idaho, Nevada, Washington, etc.) almost half or more of their territory is owned by the National Forest Service or the Bureau of Land Management. Some other federal laws regulate possession and use of weapons, the use of lead in hunting, movement of motor vehicles, access and use, etc.

It is worth pointing out that in the USA each state has its own particular structure with substantial differences:

-

In some states landowners are involved in hunting programs.

-

In others, the owner can “manage in his own way” the game that lives on his land or comanage it with the authorities.

-

In other cases (gated property), they have an almost exclusive powers of control.

The licenses for the culling of some wild animals (over-the-counter tags) can be purchased directly (together with the annual hunting license) at the point of sale or online. For other wild animals, the hunter purchases a “lottery” ticket and the culling licenses are assigned by extraction (at random). Some permits are linked to particular territories (hunting units); other permits depend on the type of game, meaning a hunter can hunt in larger areas or even the entire state. A “preference point” system gives a percentage advantage to those hunters who have not won in previous years: 14–16 points for the pronghorn and 2–3 for the mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus).

The cost of the license ranges from USD 160 (nonresidents), USD 32 (residents) to USD 6 (pioneers, i.e., 50 years of residence in Oregon) and even free for disabled war veterans. Young people pay USD 10 and the minimum age to get the license is 9–12 years old but they must be accompanied by an adult aged 21 or over (unless they hunt on lands owned by a parent or a legal guardian).

Oregon has about 200,000 hunters (5% of total population). It is worth noting that the percentage of hunters is lower in urban areas, while it is much higher in rural areas.

A course is required, for individuals that are 18 years of age and younger, to purchase the yearly hunting license. This hunter education course has an average duration of 14–16 hours and requires both classroom time and a “live fire” test in the field. In recent years, several school districts have allowed hunting education courses to be offered, as after-school programs. These courses are taught in school by volunteers certified as hunter education instructors who are often school teachers.

The hunting seasons vary depending on the species and the type of weapon (bow, pistol, muzzle-loading rifle, shotgun, or carbine) which is determined based on the lethality of the mean: more lethal, e.g., carbine = less time. The maximum period concerns migratory game as well as ducks and geese (about 90–120 days), black bear (3 months), and the puma (11 months).

In Oregon, hunting activities and wildlife conservation practices coexist in a delicate context of increased urbanization and a slow decrease of participation in hunting activities. However, despite these general challenges, hunters are still strongly committed to earning their hunting privileges by paying out of their own pockets (by purchasing hunting licenses, tags, P&R Act, and other fees) for education, habitat restoration, law enforcement, wildlife research, and management programs. This model (the North American Wildlife Management and Conservation System) of direct involvement and support has made good contributions to the preservation and protection of the wildlife patrimony and of hunting heritage (Mahoney 1995).

15.4 Case Study 4 Safari Club International

Safari Club International (SCI) is an international organization of hunters that was founded in 1972 in the USA.

The aim of SCI is to protect the freedom to hunt and therefore to promote wildlife conservation. Today SCI has about 50,000 members (84% USA, 6% Canada, 5% Europe, 4% other countries) and 200 local branches.

The Safari Club International Foundation, a branch of SCI, promotes international projects to restore wildlife conservation and to fight against poaching and believes that wildlife conservation would not be possible without hunters (Safari Club 2017).

Between 2000 and 2016, SCI Foundation invested USD 60 million in conservation, education, and humanitarian services and funded over 80 wildlife conservation projects in more than 27 countries. (Safari Club International Foundation, pers. comm).

For example, between 2008 and 2016:

-

North America. The investment was more than USD 3 million including 21 species in 16 US states, four Canadian provinces, and Mexico. Featured projects: Michigan predator-prey, Alaska wood bison reintroduction, Missouri black bear, Newfoundland woodland caribou, and Arizona desert bighorn sheep reintroduction.

-

Africa. The investment is more than USD 3.5 million including 12 species in 14 countries. Featured projects: African Wildlife Consultative Forum (AWCF), Tanzania lion, Zambia lion, Namibia leopard, and Tanzania Ruaha buffalo.

-

Asia. The investment is more than USD 1 million including ten species in five countries. Featured projects: Tajikistan argali sheep and snow leopard projects in Mongolia, Pakistan, and Russia.

SCI published the Safari Club International Record Book, which is the largest record keeping system of this kind, in the world. Trophies are measured and listed according to the size of horns and antlers, to where and how they are taken, and to their specific quality and form.

Most SCI members are interested in big game animals but they are not the majority of trophy hunters. A rough estimate of this category is about 10–20% (8.5 million) of hunters around the world (T. Terzi pers. comm. 2018).

SCI has been often criticized for supporting the hunting in high fenced game ranches where, for example, less valuable species are replaced by more valuable species and predators are therefore persecuted. In addition, fencing on game ranches fragments wildlife populations, leading to the disruption of dispersal and migratory movements (Ripple et al. 2016).

Other criticalities are the giving of awards for hunting leopards, elephants, lions, rhinos, and buffalos in Africa. SCI responds to this second problem by saying hunting provides needed funds for habitat preservation and enhancement and that SCI has enhanced the propagation or survival of several species by rescuing these species from near extinctions and providing the founder the stock necessary for reintroduction.

The first problem is actually not a simple question because SCI members are debating “if and how” to evaluate the trophies from “canned wildlife” (animals in enclosure). Therefore, recently SCI has been opposing the hunting of African lions bred in captivity.

SCI supports the thesis of “use it or lose it” talking about wildlife conservation, i.e., hunting and opposition to poaching. “If hunting tourism is suspended, instead of having legal hunting, there will be illegal hunting,” says Dr. Adelhelm Meru, Tanzania’s Permanent Secretary for the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism.

15.5 Case Study 5 Trophy Hunting in Sub-Saharan Africa

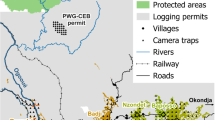

This activity covers about seven countries that extend over about 5.5 million km2 (18% of Africa) with about 180 million inhabitants (15% of Africa’s current population) and a density of 30 inhabitants per km2, less than that of Africa as a whole continent (around 40/km2) (See Table 8.2).

The protected areas cover about 29% (ranging from 6% in South Africa to 43% in Namibia) while game ranches cover 17.5% (ranging from 10.5% in Mozambique to 26% in Tanzania). In this part of Africa (about a fifth of the total area) the annual income deriving from trophy hunting for the trophy itself, generally the big four (elephant, buffalo, lion, and leopard) and other species as impala (Aepyceros melampus), warthog (Phacochoerus africanus), greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius), zebra (Equus quagga), chacma baboon (Papio ursinus), Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), and lechwe (Kobus leche), from 2009 to 2013 amounted to USD 217.2 million, with USD 40 per km2 (ranging from USD 5 to 60, Zambia and Tanzania) (Di Minin et al. 2013a; Di Minin 2016).

Considering that the minimum wage in this part of Africa is about USD 3000 per year, the figures would seem quite important, especially in Namibia and Botswana, precisely to support the local economy, even because it is believed that in general within the Campfire projects about 75% of the income (of the hunting for trophies) goes to local populations, according to credible local sources. Botswana, however, banned hunting in 2014, with negative results for conservation due to the increase in poaching and culling through PAC [problem animal control] (on lions attacking livestock and elephants for damage to agriculture or for breaking fences in order to enter farms).

In general, the illegal market of parts of the body of endangered and charismatic species has assumed incredible dimensions with rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis and Ceratotherium simum) horn dust estimated on the black market to about USD 60–100,000 per kg (Goga and Salcedo Albarán 2017). Worked and inlaid ivory on the Asian market costs up to USD 10,000 per kg according to Gao and Clark (2014).

The problem of the fight against poaching (Roe et al. 2017) as a control of species, which are harmful to agriculture and other communities’ traditional activities, is at a turning point, in the sense that they are part of the human-wildlife conflict (HWC), which is not a recent concern in Africa. Resources are necessary for the repression of poaching, but if local populations believe that wildlife is a source of damage (and often it is so, from their point of view), then every battle for conservation is lost (Di Minin et al. 2015).

There are a significant number of trophy hunting programs where indigenous or local communities have freely chosen to use trophy hunting as a tool to provide the incentives and revenue to help them conserve and manage their wildlife and/or improve their livelihoods (IUCN 2016).

Furthermore, the communities benefit directly from TH through the concessions or other investments deriving from it, which can be invested in schools or clinics, as well as in employment directly dependent on the organization of TH including guides, game guards, wildlife managers, and other hunting-related employment. In addition, the hunting product is also a consumable resource (meat) and in many communities there are no alternatives (Lindsey et al. 2006).

For these above reasons, all the coexistence with the conservation of TH is essential and given some critical issues, Di Minin et al. (2016) suggest a set of proposals:

-

1.

Mandatory levies should be imposed on safari operators by governments so that they can be invested directly into trust funds for conservation and management.

-

2.

Eco-labeling certification schemes could be adopted for trophies coming from areas that contribute to broader biodiversity conservation and respect animal’s welfare concerns.

-

3.

Mandatory population viability analyses should be done to ensure that harvests cause no net population declines.

-

4.

Post-hunt sales of any part of the animals should be banned to avoid illegal wildlife trade.

-

5.

Priority should be given to fund trophy hunting enterprises run (or leased) by local communities.

-

6.

Trust funds to facilitate equitable benefit sharing within local communities and promote long-term economic sustainability should be created.

-

7.

Mandatory scientific sampling of hunted animals, including tissue for genetic analyses and teeth for age analysis, should be enforced.

-

8.

Mandatory 5-year (or more frequent) reviews of all individuals hunted and detailed population management plans should be submitted to government legislators to extend permits.

-

9.

There should be full disclosure to public of all data collected (including the sums levied).

-

10.

Independent government observers should be assigned randomly and without forewarning on safari hunts whenever they take place.

-

11.

Trophies must be confiscated and permits must be revoked when illegal practices are disclosed.

-

12.

Backup professional shooters and trackers should be present for all hunts to minimize welfare concerns.