Abstract

The role of the intensive care unit in critically ill patients with a hematological malignancy has been a subject of discussion for years. An increase in survival rates of patients with a hematological malignancy has been observed over the last decades due to improvement in diagnostic methods, more effective treatments, and a better understanding of complications. Historically, the mortality of patients with a hematological malignancy requiring ICU admission was high, especially when the patient required mechanical ventilation or renal replacement therapy. Survival rates now differ considerably. Nonetheless, the ICU mortality rate in these patients has dropped impressively compared to the past, and 1-year survival rates up to 50% have been observed. The literature regarding quality of life after ICU admission is scarce and heterogeneous. Patients with a hematological malignancy may experience a decline in quality of life after ICU admission. However, some studies showed no difference between quality of life of patients admitted to the ICU compared to patients without ICU admission. Therefore, an ICU admission should be considered individually. Denial of ICU admission solely on the prejudice of quality of life is no longer justified. Thus, where the admission of patients with a hematological malignancy may have been a Sisyphean task in the past, recent outcome data of these patients suggest a work in progress.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Approximately 40% of the world’s population will be diagnosed with a malignancy at some point during their life [1]. In 2012, one-quarter of the global burden of cancer was observed in Europe whereas the total population of Europe represented only 9% of the world’s population [2]. In 2015, malignancies were still a major cause of death across the European Union with an average of 261 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants [3]. However, due to progress in early detection and treatment, long-term survival from malignancy has increased over the past decades [4]. Between 2011 and 2016 cancer mortality decreased in both men (8%) and women (3%) [5]. In 2018, there were an estimated 3.91 million new cases of malignancy and 1.93 million deaths from cancer in Europe [2]. The most common malignancies were female breast cancer and colorectal cancer [2]. Over the last decades, the incidence of hematological malignancies has increased as well [6,7,8]. Approximately 2.2% of the population will be diagnosed with a non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and 1.6% with leukemia [1]. The incidence of hematological malignancies is expected to grow in the future as a result of the aging population and the inability to prevent most cases [6]. As the mortality rate has been decreasing during the past decades [5, 9, 10] and the probability of infiltrative, infectious, or toxic life-threatening events related to therapy has been increasing [11], the burden of these malignancies to healthcare systems is likely to increase. This is especially the case when considering the role of the intensive care unit (ICU) in both the initial treatment and the treatment of these complications. A historical reluctance to admit patients with malignancies to the ICU, especially hematological malignancies, exists [12,13,14,15]. However, given the new therapies available, the encouraging survival data, and the possible benefits of an ICU admission, ICU admission should be considered.

The aim of this clinical review is to describe the development of the prognosis of adult patients with a hematological malignancy and the role of the ICU over the past years and in the future.

2 Survival and Prognosis of Patients with Hematological Malignancies

As is currently the case, the survival of patients with hematological malignancies varied in the past, depending on the type of hematological malignancy. The literature showed a dramatically low 5-year survival for most leukemias in 1974–1976, especially for acute myeloid leukemia (only 6%) [16]. In contrast, 71% of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma survived 5 years in this period. Between 1974 and 1996, the 5-year survival for leukemias, myelomas, and lymphomas increased [6, 16]. In the subsequent years (1996–2012), the 5-year survival for these hematological malignancies also improved, varying from a still relatively poor prognosis for acute myeloid leukemia (15–21%) to a very acceptable outcome for Hodgkin’s lymphoma (86–92.8%) [1, 10, 16,17,18,19,20]. All of the hematological malignancies described above have shown stabilized or improved 5-year survival rates for the period 2008–2012. Therefore, the outcome of patients with a hematological type of cancer may further improve in the future.

There are several reasons for this increasing survival rate of patients with hematological malignancies [6, 10, 11, 16, 17, 20]: improvements in diagnostic methods, diagnosis being made earlier than before, and more effective treatments. Moreover, advances in molecular biology make it possible to recognize low-grade malignancies with good prognosis . In addition, effective high-dose treatment regimens and targeted treatments have been introduced. Lastly, the complications observed after therapy are better understood and consequently there has been an increase in adequate treatment of these complications. However, despite this encouraging change, improvements in survival for hematological malignancies have not been uniform across Europe [10, 17]. Substantial regional differences in survival rates are seen for different types of hematological cancer. Data show variation across countries and between northern, southern, western, and eastern Europe. On average, survival in eastern European countries is lower compared to the rest of Europe. This difference could be explained by inequalities in provision of care concerning diagnostics and therapy or heterogeneity in case definition. Unsurprisingly, age at diagnosis is a strong prognostic factor [5, 10, 17, 20]. Elderly patients experience limitations of (aggressive and curative) treatment due to the prevalence of comorbidities and frailty. Furthermore, after adjustment for age and country, the data show a significant difference in survival between men and women [5, 10, 20]. Possible explanations are a lesser impact of comorbidities, as well as behavioral and biological factors [10].

3 ICU Admission Practices for Patients with Hematological Malignancies: Historical Perspective

Historically, the mortality of patients with a hematological malignancy requiring ICU admission was high. In 1983, Schuster et al. [15] reported an 80% hospital mortality in 77 critically ill patients with a hematological malignancy admitted to the ICU; survival was particularly low when patients required mechanical ventilation. In 1988, Lloyd-Thomas et al. [13] reported a mortality rate of 78% in 60 patients with a hematological type of cancer admitted to the ICU. The mortality rate was consistently higher than predicted from a large validation study of the APACHE II score in a mixed population of critically ill patients. In 1990, Brunet et al. [12] published an ICU mortality rate of 43% and a 1-year survival rate of 19% in 260 patients with a hematological malignancy. Patients who required mechanical ventilation or renal replacement therapy (RRT) showed an increased ICU mortality rate. They concluded that life support should be initiated, but that the combination of RRT and mechanical ventilation was associated with a poor prognosis . With an ICU mortality of 80–90% between 1984 and 1993, Ewig et al. [21] expressed their concerns about the low survival rates of patients with pulmonary complications admitted to the ICU. In the same time period (1980–1992), Rubenfeld et al. noted a mortality rate of 94% in 865 mechanically ventilated patients after bone marrow transplantation [14]. Of the patients with lung injury requiring mechanical ventilation combined with hemodynamic instability , hepatic failure, or renal failure, no one survived. However, the survival rate of critically ill bone marrow transplant patients increased over time, from 5% in 1980 to 16% in 1992. In summary, mortality rates of patients with a hematological type of cancer who required admission to the ICU were high in all five studies [12,13,14,15, 21].

In subsequent years, between 1990 and 2005, the hospital mortality rate ranges from 41% to 85% [22,23,24,25,26]. A high risk of refusal of ICU admission for critically ill cancer patients in this period is still seen [27]. This could be explained due to the discouraging mortality rates of previous studies and due to the recommendations of the North American and European Societies of Critical Care Medicine for ICU admission, discharge, and triage [28, 29] in which it is stated that oncologists and intensivists should reserve ICU admission for select cancer patients with a “reasonable prospect of substantial recovery.”

4 ICU Admission Practices for Patients with Hematological Malignancies: The Modern Area

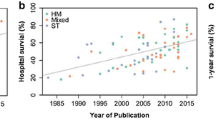

Large numbers of patients with a malignancy are nowadays admitted to the ICU (15–20% of all patients) [30,31,32]. Despite a substantial improvement in the survival of critically ill patients with cancer [8, 33, 34], the recent literature concerning critically ill patients with a hematological malignancy is heterogeneous and survival rates differ considerably [8]. ICU and hospital survival vary from 0% to 88% [35,36,37,38,39,40] and from 0% to 72% [35, 38, 39, 41], respectively. The literature shows that short-term mortality is related to the severity of illness (and organ dysfunction) rather than the underlying malignant diagnosis [8]. Although 1-year mortality may be good (almost 50%) [40], long-term mortality is still limited with a reported 8-year survival rate of only 9% [36]. Data show a decrease in long-term survival of patients admitted to the ICU, in comparison to patients who did not require admission to the ICU [36, 42]. Nonetheless, the ICU mortality rate has decreased impressively compared to the past [41, 43], with an annual decrease of 4–7% between 2003 and 2015 [43]. Based on this improvement in survival and the possible benefits of intensive care treatment, ICU admission should be considered in every patient. Thiéry et al. [27] conducted a study of cancer patients for whom ICU admission was requested. They found that 20% of patients who were not admitted because they were considered “too well” died before hospital discharge, and 25% of the patients who were not admitted because they were considered “too sick” survived. Thus, the clinical evaluation was neither sensitive nor specific for selecting patients for ICU admission. Denial of ICU admission solely on a patient having cancer is not supported by recent outcome data.

The striking difference in survival of critically ill patients with a hematological malignancy across studies and hospitals may be explained by several factors . First, studies reporting high survival rates usually originate from high-volume centers and so the external validity of these data may be limited [11]. Second, the performance status of the patient is a strong predictor of mortality and may differ between studies [8]. Third, timing of admission of patients to the ICU may differ across hospitals. Up to 50% of patients referred to the ICU are not admitted immediately [27]. Early admission is recommended, because improved outcomes associated with early admission have been found in several studies [8, 11, 33]. Bed availability may be an issue in some hospitals, thereby negatively influencing the outcome [8].

Azoulay et al. generated several hypotheses regarding the causes of delayed ICU admission and its relationship to mortality [11] (Box 39.1):

-

1.

Patient related : Patients may interpret acute symptoms as inevitable manifestations of their malignancy or may lack the social support or financial resources needed to obtain medical advice. As a consequence, hospitalization may be delayed and, in case of critical illness, ICU admission may be delayed as well.

-

2.

Disease related : Acute illnesses could develop in a fulminant way in patients with severe immunodeficiency. Subsequently, fast deterioration may occur, with severe (multiple) organ dysfunction. As a result, ICU treatment might be too late to prevent death.

-

3.

Ward related : First, suboptimal patient evaluation on the wards may result in an underestimation of disease severity followed by an unexpected clinical deterioration. Second, when the prognosis is unclear and possibly poor, ICU referral may be difficult and subsequently delayed.

-

4.

ICU related : Likewise, ICU admission decisions could be difficult and delayed in case of an unclear (poor) prognosis. In addition, a delay in optimal care may arise from the initial admission to an ICU ill equipped to manage patients with hematological malignancies with healthcare providers inexperienced in caring for hematological patients. Finally, bed availability may be an issue in some hospitals, resulting in delayed admission.

Box 39.1 Causes of delayed ICU admission in patients with hematological malignancy and recommendations for change

Factor | Causes of delayed ICU admission | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

Patient related | Misinterpretation of acute symptoms Lack of social support or financial resources (delayed hospitalization) | Education regarding alarm symptoms Explanation of relevance of social support Health insurance |

Disease related | Fast deterioration of immunocompromised patients | Use of the modified early warning score and rapid response system |

Ward related | Suboptimal patient evaluation Unclear (poor) prognosis | Use of the modified early warning score and rapid response system Close collaboration between hematology department and intensive care |

ICU related | Unclear (poor) prognosis Ill-equipped ICU with inexperienced healthcare providers Bed availability in ICU | Close collaboration between hematology department and intensive care Close collaboration between experienced hospitals and less experienced hospitals Early aggressive treatment outside the ICU Time-limited or intensity-limited ICU trials |

Some of the causes described above are amendable (Box 39.1). First, to reduce patient-related factors, education concerning alarm signals may improve patient knowledge [11]. The relevance of social support should be explained as well. Although individual financial problems are difficult to solve, national healthcare policies could play an important role in this.

Second, to improve ICU-related factors, good communication and close collaboration between different specialties and different hospitals are recommended [8, 11, 33]. For example, daily formal meetings between the attending hematologists and intensivists [8], advice from intensivists at centers managing large numbers of hematological patients to less experienced intensivists [11], and help from nurse consultants of the hematology department concerning hematological care [8] can be beneficial. In hospitals where ICU bed availability is limited, early aggressive treatment can be initiated outside the ICU [8, 11]. Furthermore, an ICU bed could be used for time-limited or intensity-limited trials , thus improving the chance of survival [8, 11]. Admittance to the ICU for end-of-life care is not recommended, because avoidance of ICU admissions within 30 days of death and death occurring outside the hospital were associated with perceptions of better end-of-life care [44].

Third, concerning the suboptimal evaluation of critically ill patients on the hematological ward, early detection of patient deterioration using the modified early warning score (MEWS) and a rapid response system has proven to be effective in enhancing ICU admission [8].

In summary, although ICU survival rates have been a major reason to deny admission in the past, steadily improving ICU survival rates have been observed in recent years. Denial of ICU admission solely based on the presence of a hematological malignancy is no longer supported by recent outcome data.

5 Quality of Life of Patients with a Hematological Malignancy Following ICU Admission

With the improvement in (long-term) survival of patients with a hematological malignancy, questions concerning the quality of life of these patients arise. Literature shows impairment of quality of life, measured by validated questionnaires, compared to their previous state or to the general population [45, 46]. Studies report either physical symptoms, such as fatigue, pain and reduction of vitality, or psychosocial symptoms, including increased levels of anxiety and depression. Mostly, data show a combination of both. A subset of patients with hematological malignancy treated with chemotherapy experience cognitive impairment [47].

Recent literature concerning the quality of life of patients with a malignancy after admission to an ICU is scarce. Oeyen et al. [48] conducted a study to assess long-term outcomes and quality of life in critically ill patients with hematological or solid malignancies, which included quality of life at 3 months and 1 year after discharge, compared to the quality of life before ICU admission. Initially, quality of life declined at 3 months. At 1 year after ICU discharge, quality of life did improve; however it remained under the baseline quality of life. Ehooman et al. showed a strongly impaired quality of life in patients with a hematological malignancy compared to general ICU patients with septic shock at 3 months and 1 year after ICU discharge [39].

By contrast, van Vliet et al. [49] compared patients with hematological malignancies admitted to the ICU with matched patients not admitted to the ICU. Eighteen months after admission, no significant difference in quality of life was found between those groups, other than a lower physical functioning score. Similarly, Azoulay et al. [50] conducted a prospective, multicenter cohort study including 1011 critically ill patients with a hematological malignancy. On day 90, 80% of survivors had no quality-of-life alterations (physical and mental health similar to that of the overall cancer population). After 6 months, 80% of survivors had no change in treatment intensity compared with similar patients not admitted to the ICU.

Patients with a hematological malignancy may experience a decline in quality of life after ICU admission. However, some studies showed no difference in quality of life of patients admitted to the ICU compared to that of patients without ICU admission. Therefore, the benefits of ICU admission for a patient with a hematological malignancy should be considered individually. Denial of ICU admission solely based on a prejudice about quality of life is no longer justified.

6 Conclusion

The incidence of hematological malignancies has increased over the past decades with an increasing (long-term) survival rate. Subsequently, the burden to the healthcare system and also referrals to the ICU will probably increase. Where meager ICU survival rates in the past have been a major reason to deny admission, current survival rates no longer justify this general approach. On the contrary, ICU admission of critically ill patients with a hematological malignancy should be considered and tailored to patient-specific characteristics. Thus, where the admission of patients with a hematological malignancy may have been a Sisyphean task in the past, recent outcome data of these patients suggest a work in progress.

References

National Cancer Institute 2016 (Updated 13 September 2018). https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html. Accessed 9 Nov 2019.

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:356–87.

Eurostat Statistics 2015 (Updated 7 September 2018). http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Causes_of_death_statistics. Accessed 9 Nov 2019

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391:1023–75.

Malvezzi M, Carioli G, Bertuccio P, et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2016 with focus on leukaemias. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:725–31.

Lichtman MA. Battling the hematological malignancies: the 200 years’ war. Oncologist. 2008;13:126–38.

Cancer Research UK 2014 (Updated 3 July 2017). http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/leukaemia/incidence#ref-2. Accessed 9 Nov 2019.

Azoulay E, Schellongowski P, Darmon M, et al. The Intensive Care Medicine research agenda on critically ill oncology and hematology patients. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1366–82.

Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Malvezzi M, et al. Cancer mortality in Europe, 2005–2009, and an overview of trends since 1980. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2657–71.

De Angelis R, Minicozzi P, Sant M, et al. Survival variations by country and age for lymphoid and myeloid malignancies in Europe 2000–2007: results of EUROCARE-5 population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2254–68.

Azoulay E, Pene F, Darmon M, et al. Managing critically ill hematology patients: Time to think differently. Blood Rev. 2015;29:359–67.

Brunet F, Lanore JJ, Dhainaut JF, et al. Is intensive care justified for patients with haematological malignancies? Intensive Care Med. 1990;16:291–7.

Lloyd-Thomas AR, Wright I, Lister TA, Hinds CJ. Prognosis of patients receiving intensive care for lifethreatening medical complications of haematological malignancy. Br Med J. 1988;296:1025–9.

Rubenfeld GD, Crawford SW. Withdrawing life support from mechanically ventilated recipients of bone marrow transplants: a case for evidence-based guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:625–33.

Schuster DP, Marion JM. Precedents for meaningful recovery during treatment in a medical intensive care unit. Outcome in patients with hematologic malignancy. Am J Med. 1983;75:402–8.

Wigmore TJ, Farquhar-Smith P, Lawson A. Intensive care for the cancer patient—unique clinical and ethical challenges and outcome prediction in the critically ill cancer patient. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2013;27:527–43.

Sant M, Minicozzi P, Mounier M, et al. Survival for haematological malignancies in Europe between 1997 and 2008 by region and age: results of EUROCARE-5, a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:931–42.

Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland Survival 2017. http://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl/selecties/Dataset_2/img59b682b776106. Accessed 9 Nov 2019.

Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Botta L, et al. Burden and centralised treatment in Europe of rare tumours: results of RARECAREnet—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1022–39.

Visser O, Trama A, Maynadie M, et al. Incidence, survival and prevalence of myeloid malignancies in Europe. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3257–66.

Ewig S, Torres A, Riquelme R, et al. Pulmonary complications in patients with haematological malignancies treated at a respiratory ICU. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:116–22.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Compliance with triage to intensive care recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2132–6.

Benoit DD, Hoste EA, Depuydt PO, et al. Outcome in critically ill medical patients treated with renal replacement therapy for acute renal failure: comparison between patients with and those without haematological malignancies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:552–8.

Cherif H, Martling CR, Hansen J, Kalin M, Bjorkholm M. Predictors of short and long-term outcome in patients with hematological disorders admitted to the intensive care unit for a life-threatening complication. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:1393–8.

Pene F, Aubron C, Azoulay E, et al. Outcome of critically ill allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation recipients: a reappraisal of indications for organ failure supports. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:643–9.

Rabbat A, Chaoui D, Lefebvre A, Ret a. Is BAL useful in patients with acute myeloid leukemia admitted in ICU for severe respiratory complications? Leukemia. 2008;22:1361–7.

Thiery G, Azoulay E, Darmon M, et al. Outcome of cancer patients considered for intensive care unit admission: a hospital-wide prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4406–13.

Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge, and triage. Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:633–8.

Consensus statement on the triage of critically ill patients. Society of Critical Care Medicine Ethics Committee. JAMA. 1994;271:1200–3.

Soares M, Caruso P, Silva E, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with cancer requiring admission to intensive care units: a prospective multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:9–15.

Taccone FS, Artigas AA, Sprung CL, Moreno R, Sakr Y, Vincent JL. Characteristics and outcomes of cancer patients in European ICUs. Crit Care. 2009;13:R15.

Bos MM, de Keizer NF, Meynaar IA, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Jonge E. Outcomes of cancer patients after unplanned admission to general intensive care units. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:897–905.

Kostakou E, Rovina N, Kyriakopoulou M, Koulouris NG, Koutsoukou A. Critically ill cancer patient in intensive care unit: issues that arise. J Crit Care. 2014;29:817–22.

Darmon M, Bourmaud A, Georges Q, et al. Changes in critically ill cancer patients’ short-term outcome over the last decades: results of systematic review with meta-analysis on individual data. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:977–87.

Corcia Palomo Y, Knight Asorey T, Espigado I, Martin Villen L, Garnacho Montero J. Mortality of oncohematological patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation admitted to the intensive care unit. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:2665–6.

Schellongowski P, Staudinger T, Kundi M, et al. Prognostic factors for intensive care unit admission, intensive care outcome, and post-intensive care survival in patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: a single center experience. Haematologica. 2011;96:231–7.

Ahmed T, Koch AL, Isom S, et al. Outcomes and changes in code status of patients with acute myeloid leukemia undergoing induction chemotherapy who were transferred to the intensive care unit. Leuk Res. 2017;62:51–5.

Belenguer-Muncharaz A, Albert-Rodrigo L, Ferrandiz-Selles A, Cebrian-Graullera G. Ten-year evolution of mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory failure in the hematological patient admitted to the intensive care unit. Med Int. 2013;37:452–60.

Ehooman F, Biard L, Lemiale V, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life of critically ill patients with haematological malignancies: a prospective observational multicenter study. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9:2.

Saillard C, Elkaim E, Rey J, et al. Early preemptive ICU admission for newly diagnosed high-risk acute myeloid leukemia patients. Leuk Res. 2018;68:29–31.

Algrin C, Faguer S, Lemiale V, et al. Outcomes after intensive care unit admission of patients with newly diagnosed lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1240–5.

Mokart D, Granata A, Crocchiolo R, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning regimen: Outcomes of patients admitted to intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2015;30:1107–13.

de Vries VA, Muller MCA, Sesmu Arbous M, et al. Time trend analysis of long term outcome of patients with haematological malignancies admitted at Dutch intensive care units. Br J Haematol. 2018;181:68–76.

Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315:284–92.

Allart-Vorelli P, Porro B, Baguet F, Michel A, Cousson-Gelie F. Haematological cancer and quality of life: a systematic literature review. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e305.

Braamse AM, Gerrits MM, van Meijel B, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients treated with auto- and allo-SCT for hematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:757–69.

Williams AM, Zent CS, Janelsins MC. What is known and unknown about chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment in patients with haematological malignancies and areas of needed research. Br J Haematol. 2016;174:835–46.

Oeyen SG, Benoit DD, Annemans L, et al. Long-term outcomes and quality of life in critically ill patients with hematological or solid malignancies: a single center study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:889–98.

van Vliet M, van den Boogaard M, Donnelly JP, Evers AW, Blijlevens NM, Pickkers P. Long-term health related quality of life following intensive care during treatment for haematological malignancies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87779.

Azoulay E, Mokart D, Pene F, et al. Outcomes of critically ill patients with hematologic malignancies: prospective multicenter data from France and Belgium—a groupe de recherche respiratoire en reanimation onco-hematologique study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2810–8.

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Jelle L. Epker for his valuable and constructive suggestions while writing this clinical review. His help is very much appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

van der Zee, E.N., Kompanje, E.J.O., Bakker, J. (2020). Admitting Adult Critically Ill Patients with Hematological Malignancies to the ICU: A Sisyphean Task or Work in Progress?. In: Vincent, JL. (eds) Annual Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine 2020. Annual Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37323-8_39

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37323-8_39

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-37322-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-37323-8

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)