Abstract

Alleviating relationship distress within couple therapy requires evidence-based insights into the origins of relationship conflict and dissatisfaction. Within the current chapter, a relational need perspective on relationship distress is taken, and research empirically testing the following questions will be summarized: Does relationship dissatisfaction result from partners being unable to meet each other’s needs? And if so, what kind of needs? Is it a question of need dissatisfaction or need frustration? Does relational need frustration affect the number of times couples argue? How do partners emotionally react when their needs are unmet within their relationship? Which destructive behaviors – intended to cope with need dissatisfaction or frustration – result from a partner’s emotions? Evidence from literature review, surveys, recall/imagine research, and observational research – conducted within samples of couples and individual partners – will be presented, and implications for theory, research, and clinical practice will be discussed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

I had a terrible day at work, but he didn’t seem to care about it. It really made me feel sad and angry at the same time. When he asked me when I would start preparing dinner, I became furious and told him to make dinner himself.

Sometimes, my wife doesn’t seem to care about my opinion. Recently, she enthusiastically told me about a trip to the mountains she wanted to organize for the whole family, even though she knows I’m not into hiking. She didn’t ask for my opinion and I really felt unheard and hurt. I told her that she was being selfish and I left the room.

These vignettes describe episodes of conflict that typically occur in both distressed and non-distressed couples. Each partner has his or her own goals, needs, or preferences, and these could be conscious or unconscious, general or specific, and short term or long term (Lewin, 1948). Conflict can occur within a couple’s relationship because individuals may pursue their goals in a way that interferes with their partner’s goals or the goals of both partners may be incompatible with one another. Despite the fact that partners may be largely unaware of these goals, goal or need interference leads to conflict between partners (Bradbury, Rogge, & Lawrence, 2001). Goal interference, need frustration, and conflict between partners are considered an unavoidable part of daily human existence, as a result of partners being highly interdependent and in frequent contact with each other (Bradbury & Karney, 2014).

Despite the fact that many theorists and researchers agree that conflict involves some goal interference or goal incompatibility between two parties (Lewin, 1948), there is surprisingly little consensus in the literature about the number and kind of relational needs that matter most within intimate relationships, nor is there consensus on which needs are central in understanding relationship conflict (Vanhee, Lemmens, Moors, Hinnekens, & Verhofstadt, 2018). Furthermore, there is little empirical research on the emotional and behavioral mechanisms underlying the assumed association between need frustration and conflict in couples (see Vanhee, Lemmens, Moors, et al., 2018). In other words, how do partners emotionally react when their needs are unmet within their relationship? Which behaviors – intended to deal with need dissatisfaction or frustration – result from these emotional reactions?

Accordingly, the aim of the present chapter is to develop a better understanding of the origins of relationship conflict in order to provide more evidence-based insights into how conflicts can be addressed in couple therapy. More specifically, an exploration will be made of how partners’ frustrated needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness fuel their emotional reactions toward their partner, as well as their behavioral responses and their general levels of relationship dissatisfaction and conflict. First, a rationale for this need perspective on relationship conflict will be provided. Second, an overview of existing empirical evidence on the associations between our variables of interest will be presented. Next, a series of studies designed to provide an initial test of our predictions will be described. Finally, we consider the major conclusions that can be drawn from this research and some possible theoretical and clinical implications.

A Relational Need Perspective on Conflict: Rationale

Different Perspectives on Relational Needs

In the past few decades, theorists have proposed many ideas to explain fights and arguments between couples (see Vanhee, Lemmens, Moors, et al., 2018; Vanhee, Lemmens, Stas, et al., 2018). These vary from mismatching relational schemas compounded by poor communication skills to an imbalance of costs and benefits (Baldwin, 1992; Clarkin & Miklowitz, 1997; Rusbult, Drigotas, & Verette, 1994). One theory gaining more attention states that conflict and dissatisfaction in a relationship may have its roots in partners’ inability to meet one another’s needs. In the couple therapy literature, some contemporary therapy models consider need fulfillment to be central in intimate relationships. For instance, Sue Johnson’s Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy places a firm emphasis on the need for attachment, referring to one’s need to feel secure and connected to their partner (Johnson, 2009; see also Bowlby, 1969, 1988; Hazan & Shaver, 1987). Additionally, the fulfillment of partners’ needs for identity maintenance (i.e., to be accepted by one’s partner as one is) and for attraction and liking (i.e., feeling that one is liked and desired by one’s partner) is an important treatment focus in Leslie Greenberg and Rhonda Goldman’s Emotion-Focused Couples Therapy (see Greenberg & Goldman, 2008; see also chapter “What are the Emotions? How Emotion-Focused Therapy Could Inspire Systemic Practice” in this book).

The couple research literature also documents the role of need fulfillment in intimate relationships. Baumeister and Leary (1995) proposed the need for belonging as one of the most basic needs to be fulfilled in an intimate relationship. Anchored within Interdependence Theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978), Drigotas and Rusbult’s work (Drigotas & Rusbult, 1992) considered the needs for intimacy, emotional involvement, security, companionship, sex, and self-worth to be essential in intimate relationships (see Le & Agnew, 2001; Le & Farrell, 2009; Lewandowski & Ackerman, 2006). Furthermore, the Self-Expansion Model proposed by Aron and Aron indicates the vital importance of partners’ needs for self-expansion or self-improvement within their relationship (Aron & Aron, 1996).

Within the broader psychological literature, Self-Determination Theory (SDT) has been one of the most notable approaches to conceptualizing basic psychological needs (Deci & Ryan, 2000). SDT advances the idea that the three needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are universal, that is, that they are essential for a person’s psychological and physical well-being (Chen et al., 2015; Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Having these needs fulfilled is important in any given social environment, including within intimate relationships (La Guardia & Patrick, 2008).

As illustrated above, there is no theoretical consensus in the literature about the number and kind of relational needs that are central in understanding intimate relationship conflict and distress. A recent review stated that convincing empirical evidence is currently lacking to inform clinicians about the kinds of needs that should be focused upon in couple therapy in order to be effective in alleviating relationship dissatisfaction and instability (Vanhee et al., 2018). Within the current investigation, a focus was taken on partners’ needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as stipulated within the SDT framework. The reasons and considerations underpinning this choice will be outlined in the following section.

Partners’ Needs for Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness

First, SDT is the only needs perspective that distinguishes need satisfaction and need frustration as two separate concepts, rather than conceptualizing them as polar opposites on a scale (Vanhee, Lemmens, Moors, et al., 2018; Vanhee, Lemmens, Stas, et al., 2018; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). It is essential to create a distinction between need satisfaction and need frustration due to their differential predictive effects; it has been demonstrated that need satisfaction plays a more fundamental role in well-being, while need frustration is seen as a better predictor of malfunction and ill-being (Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch, & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, 2011; Costa, Ntoumanis, & Bartholomew, 2015; Verstuyf, Vansteenkiste, Soenens, Boone, & Mouratidis, 2013). Regarding the specific types of needs, satisfaction of the need for autonomy in intimate relationships describes partners who feel that they have agency over their actions and that they are self-governed and experience psychological freedom in their relationship. When partners feel able to attain their desired goals within the relationship and feel effective in their actions, this satisfies their need for competence. Satisfaction of the need for relatedness means that partners experience a relationship that is mutually loving, stable, and caring. Conversely, frustration of one’s need for autonomy occurs when someone feels that their partner is controlling or coercing them to behave in particular ways, against their wishes. A partner’s need for competence is frustrated when they are made to feel that they are a failure or in some way inadequate or when their partner makes them doubt their own capabilities. Finally, frustration of one’s need for relatedness describes those who feel rejected, lonely, or disliked by their partner (La Guardia & Patrick, 2008). Therefore, need dissatisfaction (i.e., the opposite of need satisfaction) concerns passivity and indifference toward a partner’s needs, whereas need frustration refers to a situation where an individual obstructs their partner’s needs in an active and direct manner. Need dissatisfaction and need frustration are consequently asymmetrically related to one another; need dissatisfaction is, by definition, covered by need frustration, while the converse is not necessarily true (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013).

Second, SDT provides one of the most comprehensive views on relational needs, as many other models deal exclusively with needs that can be captured by only one of the three needs, and in particular the need for relatedness. As a result, the needs for autonomy and competence are often neglected. For example, the needs for intimacy, emotional involvement, security, companionship, and sex, as described by Drigotas and Rusbult (1992), can all be covered by the need for relatedness. Similarly, the need for belonging (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), the need for attachment, and the need for attraction and liking, as described by EFT-C therapists (Greenberg & Goldman, 2008; Johnson, 2004), also fall under the need for relatedness. The need for identity maintenance is described by EFT-C therapists (Greenberg & Goldman, 2008) as a composite of the needs for autonomy and competence. As these examples illustrate, SDT gives equal importance to each of the three needs in a way that the aforementioned perspectives do not.

Finally, cross-cultural replication of the association between well-being and these three needs confirms the universal importance of the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Chen et al., 2015). It has been found that the three needs play an equivalent role across different cultures (Chen et al., 2015), despite the fact that, from a cultural relativistic perspective, individualistic cultures teach people to benefit more from the presence of autonomy, while collectivistic cultures teach people to benefit more from the presence of relatedness (Heine, Lehman, Markus, & Kitayama, 1999). This finding gives support to the importance of investigating each of these three needs.

Given these considerations, our research focused on the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness in intimate relationships. In what follows, an overview is given of the available empirical evidence on the association between the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness on the one hand and relationship dissatisfaction, conflict frequency, and partners’ emotions and behavior during conflict on the other hand.

Relational Needs and Relationship Conflict: Current Empirical Evidence

Relational Needs and Relationship Dissatisfaction

Relationship (dis)satisfaction is defined as partners’ subjective evaluation of the positive and negative aspects of their relationship (Fincham, Beach, & Kemp-Fincham, 1997). Conceptually, empirically, and clinically, relationship conflict and relationship dissatisfaction are strongly intertwined (see theory and research from social learning perspectives on intimate relationships; Baucom & Epstein, 1989; Jacobson & Margolin, 1979; see Bradbury & Karney, 2014). Up to this point, studies have demonstrated that greater need satisfaction (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness) is associated with higher levels of relationship satisfaction (Patrick, Knee, Canevello, & Lonsbary, 2007; Uysal, Lin, Knee, & Bush, 2012). There is also preliminary evidence for the dyadic interplay of both partners’ levels of need satisfaction in determining relationship satisfaction. More specifically, Patrick et al. (2007) found that one’s level of relationship satisfaction was not only predicted by one’s own level of need satisfaction but also by one’s partner’s level of need satisfaction. Moreover, satisfaction of someone’s relatedness need has been shown by a longitudinal study to lead to their partner perceiving increased satisfaction with their relationship over time (Hadden, Smith, & Knee, 2013). It has been found that each of the specific SDT needs is a unique predictor of relationship outcomes but that the satisfaction of the need for relatedness is most strongly associated with relational outcomes (Patrick et al., 2007).

Relational Needs and Conflict Frequency

Conflict frequency concerns the number of differences of opinion, disagreements, fights, or arguments experienced by a couple (Canary, Cupach, & Messman, 1995; Kluwer & Johnson, 2007). To the best of our knowledge, only one study examined whether relational need satisfaction shows a link with how often partners disagree. More specifically, Patrick et al. (2007) found that participants whose needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness were satisfied to a greater extent within their intimate relationship also reported coming into conflict with their partner less frequently. The frequency of conflict reported by an individual was also related to their partner’s level of need satisfaction (Patrick et al., 2007), further highlighting the association’s dyadic nature.

Relational Needs and Conflict Behavior

The conflict literature devotes much attention to couples’ behavior during conflict (Eldridge, 2009), often categorizing the nature of these behaviors as positive versus negative or as constructive versus destructive (Birditt, Brown, Orbuch, & McIlvane, 2010; Fincham & Beach, 1999). Positive/constructive conflict behaviors would include listening actively to one’s partner, raising issues in a calm and neutral manner, and working to reach agreement. Behaviors such as blaming one’s partner, shouting, showing hostility, or interrupting would fall under negative/destructive conflict behaviors (Bradbury & Karney, 2014). Withdrawing behaviors, involving a partner disengaging from the interaction either actively or passively, have also been included in this classification (Birditt et al., 2010).

Besides partners’ individual conflict behavior, researchers often focus on patterns of behavior that occur within the couple during conflict. These patterns can largely be summarized as three types: mutual constructive behavior (i.e., active and constructive engagement with the discussion by both partners); mutual avoidance (i.e., active or passive withdrawal from the discussion by both partners); and demand-withdrawal (i.e., one partner blames and criticizes the other in pursuit of change, while the other partner either avoids or withdraws from the interaction) (Eldridge, 2009).

Regarding the association with relational need satisfaction, Patrick and colleagues’ study (Patrick et al., 2007), focusing on people’s responses to conflict, demonstrated that greater satisfaction of each need is associated with responses to conflict that are more constructive and less destructive. The study also found partner effects, showing that those whose partners experience higher levels of need satisfaction respond to conflict in a less destructive way.

Relational Needs and Emotions

As one of the primary functions of emotions is to signal a (mis)match between a person’s needs and their environment (Moors, Ellsworth, Scherer, & Frijda, 2013; Scherer & Ellsworth, 2009), negative emotions can be viewed as an alarm system that shows when someone’s needs interfere or are not compatible with those of his or her partner (Carver & Scheier, 1990). Additionally, emotions prepare and motivate people to react appropriately to specific circumstances (Keltner & Haidt, 1999; Roseman, 2011). Various therapy models, such as EFT-Cs, follow the same reasoning and place a strong focus on partners’ emotions when treating couple conflict and distress (Greenberg & Goldman, 2008; Johnson, 2004). More specifically, EFT-Cs assume that emotions play a mediating role in the association between relational need frustration and relationship conflict and distress.

Regarding the association between emotions and the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, one study showed that partners who experience less need satisfaction experience a higher degree of negative emotions and a lower degree of positive emotions (Patrick et al., 2007). These associations have also been demonstrated outside the context of intimate relationships (Reis, Sheldon, Gable, Roscoe, & Ryan, 2000. Moreover, satisfaction of the needs for competence and relatedness are shown to be related to lower levels of sadness and anger (Tong et al., 2009). The satisfaction of one’s competence needs was also found to be related to fewer feelings of fear (Tong et al., 2009).

The association between partners’ negative emotions and their conflict behavior has been an important area of investigation in the couple research literature as well (e.g., Gottman, 2011; Verhofstadt, Buysse, De Clercq, & Goodwin, 2005). When negative emotions are divided into hard (i.e., anger or irritation) and soft (i.e., sadness or hurt) categories, more negative communication (i.e., criticism and defensiveness) was found to be related to hard emotions, but the links between soft emotions and more negative communication are far less consistent (Sanford, 2007).

Conclusion

In sum, within different literatures, theoretical associations have been assumed between relational needs on the one hand and relationship conflict and dissatisfaction on the other, with emotions playing a central role (see Vanhee et al., 2018, for a review). The existing evidence on the role of autonomy, relatedness, and competence needs within relationships is promising but also scarce and limited in several respects. The gaps in our knowledge on how autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs relate to relationship conflict, dissatisfaction, and emotions are outlined below, along with how our research aimed to deal with these limitations.

Research Objectives, Predictions, and Study Design

Whereas both the emotion and couple therapy literatures suggest that emotions are important in the relational need-conflict association, specific assumptions are outlined in only a few couple therapy models (Vanhee et al., 2018). More specifically, EFT-Cs assume that (a) couple conflict and relationship distress result from partners being unable to meet each other’s needs; (b) unmet needs lead to negative emotions in partners; and (c) negative emotions, accompanying unmet needs, give rise to specific behaviors in partners, resulting in negative interaction cycles between partners over time. However, despite the specificity of these hypotheses, and their centrality in EFT-Cs, research evidence on the interplay between relational needs, emotions, and relationship conflict/dissatisfaction is largely lacking.

Second, the current literature has paid little attention to the distinction between need satisfaction and need frustration. Although there are theoretical grounds by which need (dis)satisfaction may be distinguished from need frustration, up to this point, this difference has only been taken into account by studies outside the intimate relationship context. These empirical studies demonstrate that need satisfaction is a stronger predictor of well-being than need frustration and need frustration is a stronger predictor of ill-being than need satisfaction, which emphasizes the importance of maintaining this distinction. Although a need frustration perspective on relationship conflict would therefore be more appropriate, this perspective has not been adopted by any previous study on intimate relationships.

The third limitation is methodological in nature, as the studies on relational needs in intimate relationships described above have primarily relied on surveys. This is a problem as both motivational and cognitive biases may interfere with reports of participants attempting to recall, interpret, and collect past experiences into current overall impressions of their relationship (Paulhus & Vazire, 2007; Schwartz, Groves, & Schuman, 1998).

Fourth, the studies described above used samples that consisted primarily of partners engaged in relationships of short or average length (mean relationship duration ranged from 1.06 to 3.33 years). A study of long-term relationships has not yet been undertaken, to our knowledge. The generalizability of existing findings is further limited by the fact that most previous studies have tended to use samples consisting of undergraduate (psychology) students.

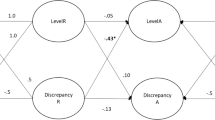

In order to deal with these shortcomings, we examined in a systematic and rigorous way how relational needs, relationship conflict, dissatisfaction, and emotions relate to each other, using multiple research methods and different samples of partners in a long-term relationship. More specifically, we examined whether (see Fig. 1):

-

Hypothesis 1. Higher levels of frustration of the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are associated with higher levels of relationship dissatisfaction and relationship conflict (higher conflict frequency and lower and higher levels of constructive and destructive conflict behavior, respectively).

-

Hypothesis 2. Higher levels of frustration of the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are associated with higher levels of sadness, fear, and anger.

-

Hypothesis 3. Sadness, fear, and anger mediate the association between the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness and relationship conflict (behavior).

In order to test our predictions, a series of five quantitative studies were conducted. Samples consisted of partners involved in a heterosexual relationship for at least 1 year and married/cohabiting for at least 6 months. The mean age for the men was 38.56 years (ranging from 18 to 77 years), and the mean age for the women was 33.12 years (ranging from 18 to 78 years). The length of their relationships ranged from 1 to 56 years, with an average length of about 14.02 years. Participants were recruited by means of social media and network sampling. Study 1 and Study 2 consisted of cross-sectional, large-scale Internet-based surveys in which 372 individuals (Study 1; Vanhee, Lemmens, & Verhofstadt, 2016) and 230 couples (Study 2; Vanhee, Lemmens, Stas, Loeys, & Verhofstadt, 2018) completed self-report measures on their level of need frustration/satisfaction within their intimate relationship, their level of relationship dissatisfaction, conflict frequency, and conflict behavior. A laboratory-based observational study was then conducted (Study 3) in which 141 couples provided questionnaire data on our variables of interest and participated in a videotaped conflict interaction and video-review task designed to measure partners’ interaction-based level of need frustration and corresponding emotions (see Vanhee, Lemmens, & Verhofstadt, in preparation). The videotaped interactions were subsequently coded for the presence of several types of conflict behavior. Within Study 4, a recall-design was used in which 200 participants described a recent self-experienced need-frustrating situation and reported on their level of need-frustration and corresponding emotional and behavioral responses (see Vanhee, Lemmens, Fontaine, Moors, & Verhofstadt, in preparation). Finally, Study 5 used a so-called imagine-design in which 397 participants reported on need frustration and emotional and behavioral responses when presented with hypothetical need-frustrating scenarios (see Vanhee, Lemmens, Fontaine, et al., in preparation).

General Summary of Results and Discussion

Relational Needs and Relationship Conflict and Dissatisfaction (H1)

Regarding relationship dissatisfaction, we found that partners’ levels of both relational need satisfaction and relational need frustration proved important in explaining their level of (dis)satisfaction in their relationship, thereby confirming both our first hypothesis and the findings of prior investigations (Patrick et al., 2007; Uysal et al., 2012). Although the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness all matter equally in intimate relationships according to Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), our findings suggested that a person’s need for relatedness was most important in evaluating their relationship, followed by their need for autonomy. An association between relationship dissatisfaction and competence needs was not found within our studies. These differential associations are in line with two earlier studies on this subject (Patrick et al., 2007; Uysal et al., 2012). Moreover, as reported in previous research (Hadden et al., 2013; Patrick et al., 2007), relationship dissatisfaction is affected by the frustration of an individual’s partner’s relatedness need as much as by their own relatedness frustration, emphasizing the central role of the need for relatedness.

Further, our research generally supported the association between relational need frustration and relationship conflict. However, autonomy, competence, and relatedness frustration seemed to play different roles depending on the component of conflict being examined. First, it was found that experiencing higher levels of relatedness frustration was associated with more frequent initiation of conflict. This is in line with Patrick and colleagues’ study (Patrick et al., 2007), which also found that relatedness was the strongest correlate of conflict frequency. Our findings on relatedness frustration further extend those of this latter study by demonstrating a partner effect in addition to an actor effect (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). This means that individuals whose partners experience greater relatedness need frustration also become more frequent initiators of conflict themselves. Second, there was a consistent finding across our studies, and thus methodologies, that greater need frustration was associated with lower levels of constructive behavior and higher levels of destructive behavior. This was true both regarding behaviors self-reported by partners in general and specific (recalled or hypothetical) need-frustrating situations and during observation of couples’ actual conflict interactions. These findings are in line with previous research addressing constructive and destructive responses to conflict more broadly, as self-reported by participants (Patrick et al., 2007). More specifically, a relationship was found between each specific type of need frustration and so-called demanding behavior. These results are in line with the existing conflict literature, which shows that people who want change in either their relationship or their partner typically display behaviors intended to elicit change in their partner, such as pressuring, accusing, or complaining (Heavey, Layne, & Christensen, 1993; Papp, Kouros, & Cummings, 2009), irrespective of the changes required (Verhofstadt et al., 2005). A positive association was also found between need frustration and conflict behavior patterns involving withdrawing behavior (such as mutual avoidance or demand-withdrawal). This might be due to the fact that withdrawing behavior is often seen as the last stage in a cascade that begins with criticizing (i.e., demanding) and escalates to contempt and defensiveness (Gottman, 1994). As such, the relationship between need frustration and withdrawing behavior might be particularly strong when relational needs are frustrated over a longer period of time.

Relational Needs and Negative Emotions (H2)

Our research provides a positive answer to the question of whether the experience of negative emotions in intimate relationships is affected by relational need frustration. These findings coincide with the suggestion of emotion theories that negative feelings function as alarms to signal that an individual’s needs interfere or are incompatible with the needs of his or her partner (Carver & Scheier, 1990; Moors et al., 2013; Scherer & Ellsworth, 2009). They also fit with SDT’s description of negative feelings as a consequence of people’s maladaptive means of coping with need frustration (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). Additionally, they are in line with previous studies outside a relationship context that have investigated the link between need dissatisfaction and negative emotions (Patrick et al., 2007; Reis et al., 2000). More specifically, it was found that the specific types of need frustration seem to play different roles depending on the type of emotion (sadness, anger, fear) being examined. In particular, we found a robust association between greater frustration of one’s relatedness needs and experiencing more sadness. The same was true for anger, with frustration of the needs for autonomy and competence being the most robust correlates in this case. These results are in line with research dividing feelings into soft and hard types, which has demonstrated that soft feelings are associated with goals focused on the relationship and hard feelings with goals centered on the self, including protecting oneself from situations leading to harm (Sanford, 2007). These latter goals can encompass the need for autonomy and competence, as autonomy frustration (for instance, feeling controlled by one’s partner) and competence frustration (for instance, feeling inferior and unsuccessful by comparison) can be viewed as harming one’s identity dimension (i.e., acceptance of who one is; Greenberg & Goldman, 2008). Within the current investigation, feelings of fear were found to be less consistently related to partners’ need frustration.

Relational Needs, Negative Emotions, and Conflict Behavior (H3)

The third part of our empirical examination involved investigating the roles of negative emotions (i.e., sadness, fear, and anger) as mediators of the association between need frustration (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness) and conflict behavior (i.e., demanding and withdrawing). Before discussing the results of our mediation analyses, it is interesting to consider the link between negative emotions and conflict behavior, as this is the mediation model’s final association that is yet to be described, despite it being essential to the mediation. Generally speaking, it can be concluded that higher levels of negative emotions, especially anger, were associated with greater instances of destructive conflict behavior and in particular of demanding behavior. Furthermore, we found that higher levels of fear were associated with less demanding behavior and more withdrawing behavior. These results confirm previous research that has shown a positive association between hard feelings and higher levels of critical and defensive behavior toward a partner. Previous studies have found that soft feelings, on the other hand, are less consistently associated with destructive communication due to the focus these place on relationship preservation and reparation (Sanford, 2007). Our findings give further support to the literature’s prevailing stance on emotions, which tends to associate anger with antagonistic tendencies, such as attempting to induce change by working against or attacking the other person, and fear with tendencies toward distancing or avoiding, which reduce interaction with one’s partner (Frijda, 1986; Roseman, 2011). Concerning demanding behavior, these findings are in line with EFT-Cs (Greenberg & Goldman, 2008; Johnson, 2004), in which this is seen as an especially likely result of anger.

In considering an overview of the significant mediationmodels that our studies found, we can conclude that individuals, particularly women, who felt that their autonomy needs were frustrated experienced higher levels of anger, which can be viewed as an emotional reaction with a self-protective purpose (Smith & Lazarus, 1990). An association was found in turn between anger and blame, criticism, and placing pressure on a partner to change, which can be viewed as attacking behaviors (Roseman, 2011; Roseman, Wiest, & Swartz, 1994). A similar association was found between frustration of competence and relatedness needs and demanding behavior via the experience of anger in both genders, although the evidence in this case was less robust. These mediation models largely converge with EFT-C’s assumptions (Greenberg & Goldman, 2008; Johnson, 2004), which argue that partners’ feelings, and in particular reactive feelings such as anger, lead to them enacting destructive behaviors toward a partner, such as demanding and withdrawing behavior, in an attempt to both cope with and protect against their own need frustration.

Implications for Theory and Practice

Our findings demonstrate that conflict can occur when individuals’ own relational needs are incompatible or interfere with their partner’s needs, which is consistent with the definition of conflict (Lewin, 1948). More specifically, our studies found that the extent to which partners’ needs are frustrated corresponds to the frequency with which they initiate conflict with their partner, as well as their feelings, behavior, and interaction with their partner when conflict arises. This proves the relevance of taking a relational need perspective on conflict.

Moreover, the present research provides further evidence that the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness is of particular importance in intimate relationships. With a basis in the broader psychological literature, previous research on the psychological needs that Self-Determination Theory describes (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 2000) has predominantly taken place within the context of the workplace, school, parenting, or sports (e.g., Haerens, Aelterman, Vansteenkiste, Soenens, & Van Petegem, 2014; Trépanier, Fernet, & Austan, 2016). Although SDT argues that the fulfillment of these needs is important regardless of the social environment, including in the context of intimate relationships (La Guardia & Patrick, 2008), few attempts had been made to support this theoretical suggestion empirically. Our results, however, also add further nuance to the equal value that SDT places on each specific type of need in an intimate relationship context (La Guardia & Patrick, 2008). Despite the fact that each of these needs contributed in some form to explaining the relational outcomes examined in our investigation (i.e., relationship (dis)satisfaction, conflict frequency, couples’ conflict behavior), it was generally found that the need for relatedness was the most important correlate of these outcomes. This is logical from a conceptual standpoint, as the key feature to define intimate relationships is interdependence (Bradbury & Karney, 2014). By contrast, the role played by each of the three needs was different, but broadly equally relevant, when it came to predicting the individual outcomes included in our investigation, such as partners’ emotions and individuals’ varieties of conflict behaviors. Therefore, it would be interesting to reconsider each need’s importance while taking into account the differing contexts and outcomes.

Our findings also reinforce SDT’s claim that creating a distinction between need satisfaction and need frustration is important, given that they have differing associations with human functioning and dysfunctioning (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013) and differential roles in relational well-being (i.e., relationship satisfaction), which is distinct from individual well-being (e.g., Bartholomew et al., 2011). With regard to relationship conflict, this research project is the first, to our knowledge, to demonstrate that it is not only partners’ passive indifference toward each other’s needs (i.e., need dissatisfaction) that affects conflict (see Patrick et al., 2007) but also more active and direct attempts by partners to undermine each other’s needs (i.e., need frustration).

The current research used samples consisting of mainly white, heterosexual, middle-class, well-functioning partners or non-distressed couples, and consequently we should exercise caution when using our findings to derive clinical implications. Our findings might nonetheless contribute to a more evidence-based insight into how couple therapists can understand and tackle couples’ relationship conflict and relationship dissatisfaction. For instance, relational need frustration is important in intimate relationships as a predictor of partners’ levels of dissatisfaction with their relationship, the frequency with which they are likely to initiate conflict with their partner, and their feelings and behavior in conflict situations. Relationship conflict and relationship dissatisfaction are the main reasons for couples seeking therapy, and couple therapists should generally recognize and tackle relational need frustration in order to address these issues. However, as the frustration of each need seems to have differential effects on a relationship, there are implications for the order in which these needs should be addressed by therapists. As the most important correlate of relational outcomes appears to be relatedness frustration, couple therapists should first explore behavior by partners that is cold and rejecting (i.e., the inducers of relatedness frustration) and focus on its reduction. It is nonetheless important that couple therapists pay attention to clients’ extreme controlling behaviors (i.e., inducers of autonomy frustration) and vague or unreasonable expectations from partners (i.e., inducers of competence frustration), as frustration of these needs has also been shown to play a role for both genders in intimate relationships. As our findings provide support for a relational need perspective on couple conflict and distress, they also imply (as suggested by an anonymous reviewer of the current chapter) that therapists should reflect on the issue of when and how to start discussing the prospects of “helpful resignation/giving up” need expectations in couples where partners cannot satisfy each other’s needs, even if they have tried for a long time.

Furthermore, our results highlight how emotions play an informative role. In line with what has been described by emotion theories (Carver & Scheier, 1990; Moors et al., 2013; Scherer & Ellsworth, 2009), we found that when an individual’s needs are incompatible or interfere with those of his or her partner, negative feelings play the role of alarms. More specifically, when partners experience anger, there might be value in exploring the extent to which an individual’s needs for autonomy and competence are frustrated by their partner. Although couple therapy sessions represent an environment in which anger is often more present, paying attention to feelings of sadness is also important, as there is a demonstrated link here with partners’ frustrated need for relatedness. Partners can also be taught ways to be receptive both to each other’s feelings and to the underlying frustrated needs. Destructive behaviors during conflict, such as demanding, are particularly related to feelings of anger, and it is through these emotions that need frustration leads to manifestations of demanding behavior. Couple therapists should use caution with these emotions due to their detrimental associations with conflict behavior. It is important to temper clients’ feelings of anger when detected and to convert these feelings into something more constructive.

Finally, concerning EFT-Cs (Greenberg & Goldman, 2008; Johnson, 2004), both our literature review and empirical data found evidence for the broad interpretation of these models’ assumptions on the etiology of relationship distress. However, as needs other than those outlined by EFT-Cs may prove to be useful, EFT-C practitioners should consider broadening their view on the needs that couple therapy ought to address (see Vanhee, Lemmens, Moors, et al., 2018; Vanhee, Lemmens, Stas, et al., 2018). Although models of effective couple therapy may not necessarily follow an understanding of the apparent causes of couple distress (Eisler, 2005), establishing empirical links between the etiology and treatment of relationship distress may contribute to emotion-focused therapies increasingly becoming theoretically grounded, research-based therapy approaches (Gurman, 2008; Lebow, 2010; Nef, Philippot, & Verhofstadt, 2012).

References

Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (1996). Love and expansion of the self: The state of the model. Personal Relationships, 3, 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1996.tb00103.x

Baldwin, M. W. (1992). Relational schemas and the processing of social information. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 461–484. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.461

Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., Bosch, J. A., & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. (2011). Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 1459–1473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211413125

Baucom, D. H., & Epstein, N. (1989). The role of cognitive variables in the assessment and treatment of marital discord. In M. Hersen, R. M. Eisler, & P. M. Miller (Eds.), Progress in behavior modification (pp. 223–248). Newbury Park, UK: SAGE.

Baumeister, R., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.117.3.497

Birditt, K. S., Brown, E., Orbuch, T. L., & McIlvane, J. M. (2010). Marital conflict behaviors and implications for divorce over 16 years. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 1188–1204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00758.x

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. I. Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bradbury, T., Rogge, R., & Lawrence, E. (2001). Reconsidering the role of conflict in marriage. In A. Booth, A. C. Crouter, & M. Clements (Eds.), Couples in conflict (pp. 59–81). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bradbury, T. N., & Karney, B. R. (2014). Intimate relationships. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Canary, D. J., Cupach, W. R., & Messman, S. J. (1995). The nature of conflict in close relationships. In D. J. Canary, W. R. Cupach, & S. J. Messman (Eds.), Relationship conflict (pp. 1–21). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1990). Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: A control-process view. Psychological Review, 97, 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.97.1.19

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., et al. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

Clarkin, J. F., & Miklowitz, D. J. (1997). Marital and family communication difficulties. In T. A. Widiger, A. J. Frances, H. A. Pinkus, R. Ross, M. B. First, & W. Davis (Eds.), DSM IV sourcebook (pp. 631–672). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Press.

Costa, S., Ntoumanis, N., & Bartholomew, K. J. (2015). Predicting the brighter and darker sides of interpersonal relationships: Does psychological need thwarting matter? Motivation and Emotion, 39, 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9427-0

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Drigotas, S. M., & Rusbult, C. E. (1992). Should I stay or should I go? A dependence model of breakups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 62–87. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.62.1.62

Eisler, I. (2005). Editorial. Journal of Family Therapy, 27, 307–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2005.0324.x

Eldridge, K. (2009). Conflict patterns. In H. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships (pp. 308–311). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. (1999). Conflict in marriage: Implications for working with couples. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 47–77.

Fincham, F. D., Beach, S. R. H., & Kemp-Fincham, S. I. (1997). Marital quality: A new theoretical perspective. In R. J. Sternberg & M. Hojjat (Eds.), Satisfaction in close relationships (pp. 275–304). New York, NY: Guilford.

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Gottman, J. M. (1994). What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gottman, J. M. (2011). The science of trust: Emotional attunement for couples. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Greenberg, L., & Goldman, R. N. (2008). Emotion-focused couples therapy: The dynamics of emotion, love, and power. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Gurman, A. S. (2008). Clinical handbook of couple therapy (4th ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hadden, B. W., Smith, C. V., & Knee, C. R. (2013). The way I make you feel: How relatedness and compassionate goals promote partner’s relationship satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9, 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.858272

Haerens, L., Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2014). Do perceived autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching relate to physical education students’ motivational experiences through unique pathways? Distinguishing between the bright and dark side of motivation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHSPORT.2014.08.013

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Conceptualizing romantic love as an attachment process. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 52, 511–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511

Heavey, C. L., Layne, C., & Christensen, A. (1993). Gender and conflict structure in marital interaction: A replication and extension. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.16

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychology Review, 106, 766–794. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.106.4.766

Jacobson, N. S., & Margolin, G. (1979). Marital therapy: Strategies based on social learning and behavior exchange principles. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel.

Johnson, S. M. (2004). Attachment theory as a guide for healing couple relationships. In W. S. Rholes & J. A. Simpson (Eds.), Adult attachment: Theory, research, and clinical implications (pp. 367–387). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Johnson, S. M. (2009). Attachment and emotionally focused therapy: Perfect partners. In J. Obegi & E. Berant (Eds.), Attachment theory and research in clinical work with adults (pp. 410–433). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Kelley, H. H., & Thibaut, J. E. (1978). Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York, NY: Wiley.

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (1999). Social functions of emotions at four levels of analysis. Cognition & Emotion, 13, 505–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999399379168

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Kluwer, E. S., & Johnson, M. D. (2007). Conflict frequency and relationship quality across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1089–1106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00434.x

La Guardia, J. G., & Patrick, H. (2008). Self-determination theory as a fundamental theory of close relationships. Canadian Psychology, 49, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012760

Le, B., & Agnew, C. R. (2001). Need fulfillment and emotional experience in interdependent romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18, 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407501183007

Le, B., & Farrell, A. K. (2009). Need fulfilment in relationships. In H. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships (pp. 1139–1141). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Lebow, J. (2010). What does research have to say about families and psychotherapy? Clinical Science Insights, 13. Retrieved from http://www.family-institute.org/research/clinical-science-insights.

Lewandowski, G. W., & Ackerman, R. A. (2006). Something’s missing: Need fulfillment and self-expansion as predictors of susceptibility to infidelity. Journal of Social Psychology, 146, 389–403. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.146.4.389-403

Lewin, K. (1948). Resolving social conflicts: Selected papers on group dynamics. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Moors, A., Ellsworth, P., Scherer, K. R., & Frijda, N. H. (2013). Appraisal theories of emotion: State of the art and future development. Emotion Review, 5, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912468165

Nef, F., Philippot, P., & Verhofstadt, L. L. (2012). L’approche processuelle en evaluation et intervention cliniques: Une approche psychologique intégrée. Revue Francophone de Clinique Comportementale et Cognitive, 17, 4–23. Retrieved from http://rfccc.be/.

Papp, L. M., Kouros, C. D., & Cummings, E. M. (2009). Demand/withdraw patterns in marital conflict in the home. Personal Relationships, 16, 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01223.x

Patrick, H., Knee, C. R., Canevello, A., & Lonsbary, C. (2007). The role of need fulfillment in relationship functioning and well-being: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 434–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022.3514.92.3.434

Paulhus, D. L., & Vazire, S. (2007). The self-report method. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 224–239). New York, NY: Guilford.

Reis, H. T., Sheldon, K. M., Gable, S. L., Roscoe, J., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167200266002

Roseman, I. J. (2011). Emotional behaviors, motivational goals, emotion strategies: Multiple levels of organization integrate variable and consistent responses. Emotion Review, 3, 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073911410744

Roseman, I. J., Wiest, C., & Swartz, T. S. (1994). Phenomenology, behaviors, and goals differentiate discrete emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.206

Rusbult, C. E., Drigotas, S. M., & Verette, J. (1994). The investment model: A interdependence analysis of commitment processes and relationship maintenance phenomena. In D. J. Canary & L. Stafford (Eds.), Communication and relational maintenance (pp. 115–139). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). The darker and brighter sides of human existence: Basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_03

Sanford, K. (2007). Hard and soft emotion during conflict: Investigating married couples and other relationships. Personal Relationships, 14, 65–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00142.x

Scherer, K. R., & Ellsworth, P. C. (2009). Appraisal theories. In D. Sander & K. R. Scherer (Eds.), The Oxford companion to emotion and the affective sciences (pp. 45–49). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Schwartz, N., Groves, R. M., & Schuman, H. (1998). Survey methods. In D. T. Gilbert, S. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 143–179). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Smith, C. A., & Lazarus, R. S. (1990). Emotion and adaptation. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 609–637). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Tong, E. M., Bishop, G. D., Enkelmann, H. C., Diong, S. M., Why, Y. P., Khader, M., & Ang, J. (2009). Emotion and appraisal profiles of the needs for competence and relatedness. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 31, 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530903058326

Trépanier, S., Fernet, C., & Austan, S. (2016). Longitudinal relationships between workplace bullying, basic psychological needs, and employee functioning: A simultaneous investigation of psychological need satisfaction and frustration. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25, 690–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1132200

Uysal, A., Lin, H. L., Knee, C. R., & Bush, A. L. (2012). The association between self- concealment from one’s partner and relationship well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211429331

Vanhee, G., Lemmens, G. M. D., Fontaine, J. R. J., Moors, A., & Verhofstadt, L. L. (in preparation). Need frustration and tendencies to demand or withdraw during conflict: The role of sadness, fear, and anger.

Vanhee, G., Lemmens, G. M. D., Moors, A., Hinnekens, C., & Verhofstadt, L. L. (2018). EFT-C’s understanding of couple distress: An overview of evidence from couple and emotion research. Journal of Family Therapy, 40(suppl. 1), 24–44.

Vanhee, G., Lemmens, G. M. D., Stas, L., Loeys, T., & Verhofstadt, L. L. (2018). Why are couples fighting? A need frustration perspective on relationship conflict and dissatisfaction. Journal of Family Therapy, 40(suppl. 1), 4–23.

Vanhee, G., Lemmens, G. M. D., & Verhofstadt, L. L. (2016). Relationship satisfaction: High need satisfaction or low need frustration? Social Behavior and Personality, 44(6), 923–930.

Vanhee, G., Lemmens, G. M. D., & Verhofstadt, L. L. (in preparation). Need frustration and demanding/withdrawing behavior during relationship conflict: An observational study on the role of sadness, fear, and anger.

Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23, 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032359

Verhofstadt, L. L., Buysse, A., De Clercq, A., & Goodwin, R. (2005). Emotional arousal and negative affect in marital conflict: The influence of gender, conflict structure, and demand-withdrawal. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 449–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.262

Verstuyf, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., Boone, L., & Mouratidis, A. (2013). Daily ups-and downs in women’s binge eating symptoms: The role of basic psychological needs, general self-control, and emotional eating. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32, 335–361. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2013.32.3.335

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Verhofstadt, L.L., Lemmens, G.M.D., Vanhee, G. (2020). Relationship Distress: Empirical Evidence for a Relational Need Perspective. In: Ochs, M., Borcsa, M., Schweitzer, J. (eds) Systemic Research in Individual, Couple, and Family Therapy and Counseling. European Family Therapy Association Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36560-8_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36560-8_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-36559-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-36560-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)