Abstract

Whether mental illness increases the risk of violence has long been a central question in psychiatry, with important implications for health policy, clinical practice, mental health law and public perception of mental illness.

In this chapter, we summarise how advances in epidemiology have improved the understanding of the relationship between mental illness and violence. The current evidence base will be outlined, which is there is an elevated relative risk of violence in most psychiatric disorders compared to the general population. For most disorders, this is small but clinically relevant. However, for some subgroups, particularly with substance use comorbidities, violence risk is further elevated and may also be a target for population-based interventions. Factors within mental illness that increase this risk will be highlighted, with an emphasis on applying such knowledge to clinical practice. Finally, the issue of bridging the gap between epidemiological evidence and individual clinical assessment will be addressed, with reference to the supporting role of risk prediction models and tools. Simple, scalable tools that have been developed and validated using current best practice in prediction modelling, such as OxMIV for the prediction of violence in schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorder, represent a step-change in the translation of epidemiological evidence into practice in the field.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

It has long been thought that there is some relationship between offending behaviour and mental illness [1]. For example, there have been hospitals providing psychiatric treatment to people with mental health problems who have criminally offended since the mid-nineteenth century [2]. In the latter part of the twentieth century, however, researchers had very contrasting views on the nature and magnitude of the relationship [3]. A prevailing expert view, reinforced by patient advocacy groups, was that controlling for demographic and life history factors dissipated the reported increased links with violence and crime [4], and studies in the early 1990s demonstrating increased risks were criticised on methodological grounds, by questioning violence outcome measurement and use of non-representative populations [5].

An influential study which sought to address some of these issues was the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment study, the first findings of which were published in 1998 [6]. In a diagnostically heterogeneous group of 951 patients discharged from three US acute inpatient facilities, community violent outcomes were triangulated from three sources (self-report, collateral informants, and police and health records) and compared with rates in the general population living in the same residential areas. The widely cited primary finding was that prevalence of violence in discharged patients without substance misuse did not differ from other individuals in the same neighbourhood without substance misuse. However, links were found with violent outcomes when for example considering diagnostic groups separately, and this study has been subject to subsequent debate and further analysis [7].

In recent years, through longitudinal use of population registers that provide more precision and allow new ways to account for confounding, a more robust and nuanced understanding has emerged. This has been supported by meta-analyses. That is, many mental disorders are associated with a small but increased risk of violence compared with the general population, which is partly explained by comorbid substance misuse. Whilst most individuals with mental illness are not violent, the risks in both relative and absolute terms, and the implications of violence for patients themselves and those affected by it, mean that assessing and reducing this risk is an important aspect of clinical psychiatric practice. Public perception of dangerousness remains central to stigma in mental illness [8], and so it is imperative that these risks are not overstated, and that context is provided—such as that individuals with mental illness are also at increased risk of crime victimisation [9] and the majority of people with mental illness will not be violent towards others. It is also increasingly appreciated however that reducing violence risk with effective treatment should form part of anti-stigma strategy [10], and being transparent about the evidence of a link is necessary for patient benefit [11].

2 Current Understanding of Violence Epidemiology in Mental Disorders

2.1 Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

A substantial proportion of the studies examining violence in mental illness have focussed on psychotic illnesses. A 2009 systematic review pooled results from 20 primary studies conducted between 1980 and 2009, incorporating data from 18,423 individuals with schizophrenia and related disorders compared with 1.7 million controls [12]. Overall, odds ratios in individual studies for the risk of any violent outcome in people with psychosis compared with the general population ranged from 1 to 7 in men and 4 to 29 in women. For individuals without substance use comorbidity, the presence of a psychotic illness was associated with a twofold increased risk of violence compared to the general population (pooled odds ratio [OR] 2.1, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.7–2.7). When including comorbid substance misuse, the pooled OR rose to 8.9 (95% CI 5.4–14.7), and when considering only homicide, the pooled OR was 19.5 (95% CI 14.7–25.8). Homicide is a rare outcome however; the absolute risk in this review was 0.3%, and in a UK national clinical survey less than 6% of all homicides were by individuals with schizophrenia and other delusional disorders (326 of 5699 homicides over 10 years) [13].

Large individual studies have since supported the findings from the review. A study that used national registries to longitudinally examine post-illness-onset offending in a random sample of 25% of the total Danish population (over ½ million individuals) found a similar magnitude of association when adjusted for age, socio-economic factors and substance misuse [14]. Rates of violent offending were also examined in a Swedish population sample of 24,297 individuals with schizophrenia and related disorders followed up for 38 years, in a study that addressed confounding by matching to both general population and unaffected sibling controls [15]. The OR for offending in patients versus their sibling controls, adjusted for low family income and being born abroad, was 4.2 (95% CI 3.8–4.5). In this Swedish sample, the absolute rates of violent offending within the first 5 years following diagnosis were 11% in men and 3% in women.

The first episode of a psychotic illness in particular is a potentially high-risk phase, with pooled evidence suggesting that a quarter of patients perpetrate some violence before treatment is initiated [16]. Longitudinally, a rate of 14% was found for the 12 months after service engagement in a UK cohort of 670 individuals with first-episode psychosis [17]. Specialist psychiatric services for individuals presenting with first-episode psychosis, typically modelled as ‘early intervention’ services, are now well established internationally and deliver a range of individually tailored interventions. This may be an important setting in which to identify higher risk subgroups at an early stage of illness, in order to target preventative approaches and reduce downstream violence and other adverse outcomes [18].

2.2 Mood Disorders

Alongside other adverse outcomes such as attempted and completed suicide, bipolar disorder has been clearly associated with violent crime [19]. A systematic review of nine studies between 1990 and 2010 (N = 6383 individuals with bipolar disorder, compared with 112,944 controls) found a pooled OR for violence of 4.6 (95% CI 3.9–5.4) compared to the general population [20, 21]. A subsequent longitudinal study of 15,337 individuals with bipolar disorder using Swedish registers found a threefold increased risk of violent crime compared to the general population after adjustment for sociodemographic factors and substance use (adjusted risk ratio 2.8, 95% CI 2.5–3.1) [19]. In this cohort, 7.9% of men and 1.8% of women were convicted for a violent crime following diagnosis, largely in the first 5 years.

The risk of violence in unipolar depression has been less studied than the psychoses. Early results were inconsistent, with some studies finding no significant relationship or weak associations that disappeared on controlling for confounders or comorbidity [22]. However, the MacArthur risk assessment study for example found that 10.3% of patients with depression without substance use were violent compared with 4.6% of the community comparison sample [23]. More recently, a study of 47,158 Swedish psychiatric outpatients with depression found a threefold increased risk of violence compared to the general population (adjusted OR 3.0, 95% CI 2.8–3.3). The absolute rates of violence in this population (3.7% in men and 0.5% in women compared to 1.2% of men and 0.2% of women in the general population) were clearly below that seen in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Highlighting these differences between relative and absolute risk remains important when communicating the findings of such studies.

2.3 Substance and Alcohol Misuse

There are challenges in understanding the relationship between drug and alcohol misuse and risk of violent offending. These include high rates of psychiatric comorbidity [24], heterogeneity in criteria defining substance misuse and considerable overlap between consumption of different drugs and alcohol [25]. The manner in which use may relate to violence is also complex, and has been broadly considered in terms of the potential effects of acute intoxication as well as the social, environmental and lifestyle factors associated with misuse [26]. Despite these issues, many studies have replicated that there is some overall significant relationship [27].

A recent umbrella review incorporated 22 existing meta-analyses of risk factors for interpersonal violence, and of these found substance misuse to have the greatest effect size (pooled OR 7.4, 95% CI 4.3–12.7), with a population attributable risk fraction of 14.8% (95% CI 9.0–21.6%) [28]. Another meta-review included 30 meta-analyses of the effect of alcohol and illicit drug use on violence published in 1985–2014, and found a significant relationship that was held across variations in study population, type of substance, and definition of violence [29]. The overall weighted estimate for standardised mean difference (effect size, where values between 0.35 and 0.65 are regarded as ‘medium’ and values above 0.65 as ‘large’) for alcohol and illicit drugs combined was 0.49 (95% CI 0.34–0.63). Such syntheses of previously published meta-analyses are helpful to provide a broad view of the relationship in an area with considerable volume and variation in research design.

There is additional strong evidence for the link between alcohol use and risk of violence. Among 292,420 men and 193,520 women who were general population controls in a Swedish total population study, the hazard ratio (HR) for violent offending for alcohol-use disorders was 9.0 for men (95% CI 8.2–9.9) and 19.8 for women (95% CI 14.6–26.7) [15]. These findings are consistent with earlier smaller longitudinal studies, such as data from a New Zealand birth cohort of 1265 individuals followed up over 30 years [30]. Based on periodic interviews, this cohort found having five or more symptoms of alcohol misuse or dependence in the prior 12 months was associated with an incidence rate ratio (IRR) for violent offending compared to those with no symptoms of 8.0 in men (95% CI 6.4–10.1) and 15.4 in women (95% CI 11.4–20.8). Increased risk has also been demonstrated in general population surveys [31, 32].

Drug-use disorders, when taken as a group separately to alcohol-use disorders, have also been clearly linked to violence risk, including in survey data [27], pooled data from 13 individual studies (random effects OR 7.4, 95% CI 4.3–12.7) [12], and Swedish population data (HR for violent offending in men of 16.2 [95% CI 14.6–17.9] and in women of 36.0 [95% CI 27.0–48.0]) [15]. Evidence is more uncertain for individual substances. A 2016 systematic review included 17 relevant longitudinal studies [33]. Findings were mixed and hampered by the low quality of primary studies. The most frequently examined substance was marijuana, with 12 measures of association from 8 studies, of which 5 showed an increased risk of interpersonal violence, 2 showed mixed results and 5 showed no association. Other subsequent studies have similarly produced inconclusive results, such as a Swedish general population survey of anabolic steroid use in men, which found a significant association with violent conviction (OR 5.0, 95% CI 2.7–9.3) that reduced when controlling for other substance misuse (OR 1.6, 95% CI 0.8–3.3) [34]. A similar decrease in association when controlling for other lifetime substance use and alcohol misuse/dependence was found for the other five non-steroid substances considered in this investigation (Rohypnol, other benzodiazepines, amphetamines, cocaine and cannabis), although the relationship remained significant for Rohypnol (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2–3.7), amphetamines (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.9–4.0) and cannabis (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.5–2.3) [34].

New synthetic agents, such as synthetic cannabinoids, have caused considerable concern including that their higher potency is associated with more adverse effects [35], particularly acutely, which may include aggression and violence. The 2015 version of the Youth Risk Behaviour Survey (N = 15,624), a cross-sectional survey of US schools, included for the first time a measure of synthetic cannabinoid use [36]. Although one of the violent outcomes, ‘engaged in a physical fight’, was significantly more likely to occur among students who ever used synthetic cannabinoids compared with students who ever used marijuana only, over 98% of those who had ever used synthetic cannabinoids had also used marijuana making it not possible to isolate any specific effects.

2.4 Personality Disorders

As well as being an important comorbidity in psychiatric and forensic populations, personality disorder as a diagnostic group has been widely demonstrated to be associated with an increased risk of violence. A study of 49,398 Swedish men assessed at military conscription and followed up in national crime registers found an increased risk of future violent conviction, OR 2.7 (95% CI 2.2–3.2) [37], and research using Danish population data has reported an adjusted IRR for violent offending of 4.1 in men (95% CI 3.5–4.7) and 5.0 in women (95% CI 3.8–6.7) [14].

A 2012 meta-analysis included 14 studies and over 10,000 individuals with personality disorder compared with 12 million general population controls [38]. The pooled OR for violent outcomes for personality disorders combined versus general population controls was 3.0 (95% CI 2.6–3.5). Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) contributed substantially; 14% of those with ASPD had a violent outcome, and when considering only studies of ASPD (excluding one outlier) the pooled OR was 10.4 (95% CI 7.3–14.0). Differential effects of different categories were further examined in a cross-sectional survey of 8397 UK adults, where ASPD was also most strongly related to violence, although paranoid, narcissistic and obsessive-compulsive also made smaller independent contributions [39]. Borderline personality disorder has also been individually considered; a systematic review did not find evidence for an independent association with violence [40], and more recent survey data found an association only with intimate partner violence [41]. Comorbidity with substance misuse and ASPD was thought to be more relevant to risk.

2.5 Neurodevelopmental Disorders

The over-representation of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in custodial settings has been reported [42, 43], and pooled data from longitudinal studies including over 15,000 individuals with childhood ADHD showed a significant association with future incarceration (which can be taken as a proxy of violent offending), with a relative risk of 2.9 (95% CI 1.9–4.3) [44]. A longitudinal study of 1366 children diagnosed with ADHD in Stockholm looked specifically at violent offending and similarly found odds of 2.7 (95% CI 2.0–3.8) when adjusted for confounders including substance use comorbidity [45].

The epidemiological literature examining the relationship between autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) and violence is limited. A 2014 systematic review found only two studies with unbiased samples, which were too small to draw meaningful conclusions [46]. More informative has been a longitudinal study of children in Stockholm, which included 954 individuals with ASD compared with 33,910 population controls. No significant association with violent offending was found in the unadjusted model (OR 1.3, 95% CI 0.9–2.0), and the association reduced further when adjusted for parental factors and comorbidity including psychoses, substance misuse and conduct disorder (adjusted OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.6–1.9) [45]. This finding has been replicated more recently in a Swedish population-based cohort study including 5739 individuals with ASD, where a small association with violent offending was attenuated after controlling for comorbidity, particularly ADHD and conduct disorder [47].

3 Risk Factors for Violence in Mental Illness

In addition to gaining understanding of the associations between the standard diagnostic categories of mental disorder and risk of violence, research has also examined specific factors that may contribute to any increased risk of violence. These factors can either be static (historical or unchangeable, such as a past criminal conviction) or dynamic (modifiable or changing over time, such as substance misuse or psychotic symptoms). Such understanding is important in order to assess risk in a more individualised manner, and, where possible, consider strategies to reduce risk.

A meta-analysis of risk factors for violence in psychotic illness considered 110 studies including 45,533 individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia (88%) bipolar disorder and other psychoses [48]. The overall prevalence of violence, defined by a variety of measures (including in 42 studies by register-based sources), was 18.5%. The review identified several important dynamic risk factors associated with violence risk, including hostile behaviour (random-effects pooled OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.8–4.2), poor impulse control (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.5–7.2), lack of insight (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.4–5.2), recent alcohol and/or drug misuse (OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.3–6.3), non-adherence with psychological therapies (OR 6.7, 95% CI 2.4–19.2) and non-adherence with medication (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.0–3.7) [48]. Static factors relating to past criminal history were robustly associated with violence, such as a history of violent conviction (OR 4.2, 95% CI 2.2–9.1) and history of imprisonment for any offence (OR 4.5, 95% CI 2.7–7.7). Other important demographic features were a history of homelessness (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.5–3.4) and male gender (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2–2.1).

In this review, negative symptoms were not linked with violence (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.9–1.2). This has been a relatively consistent finding, including in previous reviews [49], surveys [50] and prospective studies [51]. Positive symptoms were significantly associated with violence, although less strongly than other combined risk factor domains. Certain positive symptoms that have been regarded as clinically relevant [52, 53] were not demonstrated in this review to be significantly associated with violence, such as command hallucinations (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.5–2.0) and threat/control override delusions (OR 1.2, 95% CI 0.9–1.7). Other work has explored alternatives—for example, potential pathways to violence from delusional beliefs that imply threat (such as persecution or being spied on), mediated by anger related to the beliefs, were demonstrated in re-analysis of data from the MacArthur Study [54] and in a survey of 458 patients with first-episode psychosis in London [55].

Some of the factors most strongly associated with violence in this review were victimisation—whether this was violent victimisation during adulthood (OR 6.1, 95% CI 4.0–9.1), physical abuse during childhood (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.5–3.1) or sexual abuse during childhood (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.5–2.4). The overlap between violence victimisation and perpetration has been widely demonstrated both in individuals with mental disorders [9] and in the general population [56], and is suggested to arise partly from shared risk factors for the two outcomes, such as comorbidity and volatile social relationships [57]. Victimisation was shown to mediate the association between depressive symptoms and violent behaviour in adolescence in a longitudinal study of 682 Dutch adolescents [58]. Violent victimisation has also been shown to be a strong predictive trigger event for violent offending in psychotic illness in a Swedish registry study of individuals with schizophrenia spectrum or bipolar disorders [59]. This study used a within-individual design to compare the risk of an individual behaving violently following exposure to a trigger with risk for that same individual in earlier time periods of equivalent length. All of the triggers examined (exposure to violence, parental bereavement, self-harm, traumatic brain injury, unintentional injuries, and substance intoxication) increased risk in the following week, and this was strongest for exposure to violence (OR for schizophrenia spectrum disorders 12.7 [95% CI 8.2–19.6], OR for bipolar disorder 7.6 [95% CI 4.0–14.4]). These findings are potentially highly relevant to dynamic risk management in clinical practice.

The relative strengths of association between various static and dynamic risk factors and a violent crime conviction in the subsequent year have also been examined in a cohort of 58,771 individuals with schizophrenia spectrum or bipolar disorder in a Swedish national cohort [60]. The strongest association was for previous violent crime (adjusted OR 5.03, 95% CI 4.23–5.98). Significant links were also seen for example for previous alcohol-use disorder (adjusted OR 1.75, 95% CI 1.47–2.09) and being an inpatient at the time of episode (adjusted OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.18–1.59). Recent treatment with antipsychotic medication was associated with a reduced risk (adjusted OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.51–0.77).

4 Translating Epidemiology to Clinical Practice

4.1 Clinical Assessment

In general psychiatric practice, the prevalence of violence as an adverse outcome across a range of disorders should be carefully considered, at least as one component of a general assessment of risk, and this is partly reflected in international clinical guidelines for bipolar disorder [61], schizophrenia [62] and depression [63]. The emphasis placed on violence risk assessment will vary to some extent between diagnoses, based on the differences in relative and absolute risk; for example, consideration of violence risk should be a prominent aspect of the management of individuals with antisocial personality disorder, whereas an increased risk of violent offending has not been demonstrated in some neurodevelopmental disorders. The empirical evidence already discussed in this chapter provides some direction to the aspects of history taking and clinical examination that are most relevant to any assessment of violence risk.

Clinical history should focus on previous violence, including its severity (injuries inflicted, use of a weapon, whether resulted in criminal conviction or incarceration) and circumstances surrounding previous incidents (including relevant triggers, active dynamic factors such as substance misuse, symptoms of mental illness, engagement with supervision and treatment from health services or other agencies, and social circumstances). A thorough drug and alcohol use history is essential, with a focus on temporal relevance to previous incidents of violence and deteriorations in mental state, and the wider context of any use such as its impact on stability of accommodation, violent victimisation, conflicted social relationships, and behaviours associated with funding substance use. Past psychiatric history should include enquiry about past self-harm, inpatient hospital admission, and indications of impulsivity or comorbid antisocial personality, as well as exploring previous response to treatment. Background history should explore educational level, elicit any family history of violent crime or substance misuse [60], and inquire about previous traumatic brain injury [64], past victimisation and abuse. A current social history should include housing and financial circumstances, and importantly identify whether any specific individuals are at risk. Wherever possible, collateral history from those close to the individual should be sought in order to identify any such concerns.

On mental state examination, general features such as irritability and hostility should be observed. The theme and content of any delusional beliefs should be explored fully, including whether beliefs relate to a particular person with whom the individual may have contact, and noting the relevance to risk of persecutory belief systems that involve feeling threatened and paranoid. The level of distress, preoccupation and presence of any affective component to these beliefs should be examined, and the extent to which behaviour has been modified in the context of these beliefs should be probed—for example, whether the individual has taken any steps to protect themselves from a perceived threat. More generally the overall burden of positive psychotic symptoms is relevant [48]. Finally, assessment of the level of insight and likely engagement with mental health services and treatment will be integral to the immediate plans to manage any identified risks.

4.2 Treatment

One of the key purposes of understanding and assessing the risk of violence in mental illness, such as Oxford Mental Illness and Violence tool (OxMIV) is to reduce this risk. Effective treatment of several of the dynamic risk factors that are associated with violence has indeed been shown to lead to reduced rates of violence.

Due to the strength of association, targeting substance misuse (whether as a comorbidity or primary disorder) will be an important aspect of reducing risk. This may include treatment with medication. Four such medications (acamprosate, naltrexone, methadone and buprenorphine) were examined in 21,281 individuals who had been prescribed at least one of these [65]. Within-individual comparisons demonstrated decreased risks of arrest for violent crime for the opioid substitutes buprenorphine (hazard ratio [HR] 0.65, 95% CI 0.50–0.84) and methadone (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.73–0.96). In a study of Swedish released prisoners with schizophrenia spectrum disorders or bipolar disorder, treatment of co-occurring addiction disorders with medication was also shown to be associated with a substantial reduction in subsequent violent offending (HR 0.13, 95% CI 0.02–0.95), equating to a risk difference in number of violent re-offences per 1000 person years of −104.5 (95% CI −118.4 to −5.7), although caution is warranted as confidence intervals were large [66].

Appropriately treating core symptoms of mental illness with medication has also been shown to reduce the risk of violence. A Swedish population study of prescribed antipsychotics and mood stabilisers over 4 years found a 45% reduction in violent crime when individuals were prescribed antipsychotic medication compared with when they were not (hazard ratio [HR] 0.55, 95% CI 0.47–0.64), and a 24% reduction with mood-stabilising medication (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.62–0.93) [67]. Importantly, when separated by diagnosis, the reduction in violence with mood-stabilising medication was only found in those with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Clozapine has been specifically linked to an anti-aggressive effect that may go beyond improved symptom control alone [68]. In a study of individuals with a psychotic or schizoaffective disorder, prescription of clozapine was associated with a lower rate of violent offending compared with the period before treatment (rate ratio 0.13, 95% CI 0.05–0.34, N = 1004 individuals treated with clozapine for longer than 8 weeks), and had a significantly greater rate reduction effect on violent offences than olanzapine prescription [69].

Such findings support the view that effective treatment by psychiatric services can help reduce risks of violence. There is however a need for more evidence-based preventative interventions to specifically target this important adverse outcome in psychiatric populations [70]. This may be particularly relevant in certain settings and patient groups, one example being individuals presenting with first-episode psychosis (as discussed above). Here, factors such as premorbid antisocial behaviours have been shown to increase the risk of future violence independent of psychosis-related factors, and so prevention may need to go further than symptom control alone and specifically target such behaviours [17].

4.3 Risk Assessment Tools

Whilst epidemiology can help frame risk assessments broadly around those factors most empirically related to violence, one challenge for clinicians is translating this evidence more directly into clinical assessment. This will involve weighing up the relative importance of different risk factors in order to reach some quantifiable and communicable judgement of the magnitude of the risk, both in absolute terms and relative to thresholds. This may lead to identifying a need for more intensive provision of support and treatment.

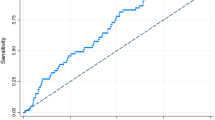

Part of the gap between epidemiology and the clinical world can be bridged through the use of risk assessment tools. Many tools facilitate a ‘structured clinical judgement’ approach, prompting clinicians to consider certain factors as a basis for their judgement of risk. However, these tools are resource intensive [71] to the extent that their practical utility outside of forensic psychiatric settings is highly doubtful, and furthermore they offer limited predictive accuracy in such settings [72]. A more effective approach may be the use of prediction models that statistically combine information about different risk factors to give an overall prediction of the risk of a particular outcome (such as a violent offence) over a particular time period. The key to the utility of such models is their translation into simple, scalable clinical tools that can then potentially act as adjuncts to clinical assessment.

Risk prediction models and tools are already integral to clinical practice in other areas of medicine, such as guiding the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease or decisions about adjuvant therapy in cancer, and are regarded as central to the advancement of healthcare delivery by data science [73]. There is promise that such models and tools may also have clinical utility for the prediction of violence in mental illness, such as Oxford Mental Illness and Violence tool (OxMIV) [60], which would facilitate a more stratified approach—in which the updated evidence is directly and accurately incorporated into the process of assessing risk. In turn, this should lead to linked interventions, particularly non-harmful ones with good evidence in support. Use of a supportive tool can introduce transparency and consistency that may be lacking from unstructured clinical assessments of risk [74]. In addition, for some services, screening out individuals accurately who are at low risk using risk tools will be clinically useful.

5 Summary

Whilst risks should not be overstated, violence risk is increased in a range of mental disorders. Large population-level datasets have clarified these associations by accounting for the temporality of disease onset and outcome, and they have provided more information on confounding factors. Among individuals with mental illness, criminal history and substance misuse factors are strongly related to increased risk, and treating modifiable factors has been shown to reduce risks. In the future, risk prediction models and tools will enable a stratified and precise approach to violence prevention in psychiatry.

References

Monahan J. Mental disorder and violent behavior. Perceptions and evidence. Am Psychol. 1992;47(4):511–21.

Stevens M. Broadmoor revealed: Victorian crime and the lunatic asylum. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Social History; 2013.

Coid JW. Dangerous patients with mental illness: increased risks warrant new policies, adequate resources, and appropriate legislation. BMJ. 1996;312(7036):965–6.

Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Crime and mental disorder: an epidemiological approach. Crime Justice. 1983;4:145–89.

Lindqvist P, Allebeck P. Schizophrenia and crime: a longitudinal follow-up of 644 schizophrenics in Stockholm. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157(3):345–50.

Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, Robbins PC, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393–401.

Torrey EF, Stanley J, Monahan J, Steadman HJ. The MacArthur violence risk assessment study revisited: two views ten years after its initial publication. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(2):147–52.

Seeman N, Tang S, Brown AD, Ing A. World survey of mental illness stigma. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:115–21.

Dean K, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Webb RT, Mortensen PB, Agerbo E. Risk of being subjected to crime, including violent crime, after onset of mental illness: a Danish national registry study using police data. JAMA Psychiat. 2018;75(7):689–96.

Torrey EF. Stigma and violence: isn’t it time to connect the dots? Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(5):892–6.

Mullen PE. Facing up to unpalatable evidence for the sake of our patients. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000112.

Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, Geddes JR, Grann M. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000120.

The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health. Annual report: England NI, Scotland, Wales. University of Manchester; 2018.

Stevens H, Laursen TM, Mortensen PB, Agerbo E, Dean K. Post-illness-onset risk of offending across the full spectrum of psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2015;45(11):2447–57.

Fazel S, Wolf A, Palm C, Lichtenstein P. Violent crime, suicide, and premature mortality in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a 38-year total population study in Sweden. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(1):44–54.

Winsper C, Ganapathy R, Marwaha S, Large M, Birchwood M, Singh SP. A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of aggression during the first episode of psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128(6):413–21.

Winsper C, Singh SP, Marwaha S, et al. Pathways to violent behavior during first-episode psychosis: a report from the UK national EDEN study. JAMA Psychiat. 2013;70(12):1287–93.

Brewer WJ, Lambert TJ, Witt K, Dileo J, Duff C, Crlenjak C, et al. Intensive case management for high-risk patients with first-episode psychosis: service model and outcomes. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(1):29–37.

Webb RT, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Geddes JR, Fazel S. Suicide, hospital-presenting suicide attempts, and criminality in bipolar disorder: examination of risk for multiple adverse outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):e809–16.

Fazel S, Lichtenstein P, Grann M, Goodwin GM, Langstrom N. Bipolar disorder and violent crime: new evidence from population-based longitudinal studies and systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(9):931–8.

Fazel S, Lichtenstein P, Frisell T, Grann M, Goodwin G, Langstrom N. Bipolar disorder and violent crime: time at risk reanalysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1325–6.

Arseneault L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor PJ, Silva PA. Mental disorders and violence in a total birth cohort: results from the Dunedin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(10):979–86.

Monahan J. Reducing violence risk: diagnostically based clues from the MacArthur violent risk assessment study. In: Hodgins S, editor. Effective prevention of crime and violence among the mentally ill. Amsterdam: Kluwer; 2000. p. 19–34.

Goldstein RB, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Grant BF. Sex differences in prevalence and comorbidity of alcohol and drug use disorders: results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(6):938–50.

Falk D, Yi HY, Hiller-Sturmhofel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and drug use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Alcohol Res Health. 2008;31(2):100–10.

Boles SM, Miotto K. Substance abuse and violence: a review of the literature. Aggress Viol Behav. 2003;8(2):155–74.

Van Dorn R, Volavka J, Johnson N. Mental disorder and violence: is there a relationship beyond substance use? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(3):487–503.

Fazel S, Smith EN, Chang Z, Geddes JR. Risk factors for interpersonal violence: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213(4):609–14.

Duke AA, Smith KM, Oberleitner LM, Westphal A, McKee SA. Alcohol, drugs, and violence: a meta-meta-analysis. Psychol Violence. 2018;8(2):238–49.

Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood L. Alcohol misuse and violent behavior: findings from a 30-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122(1–2):135–41.

Coker KL, Smith PH, Westphal A, Zonana HV, McKee SA. Crime and psychiatric disorders among youth in the US population: an analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(8):888–98, 898.e1–2

Harford TC, Yi HY, Freeman RC. A typology of violence against self and others and its associations with drinking and other drug use among high school students in a U.S. general population survey. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2012;21(4):349–66.

McGinty EE, Choksy S, Wintemute GJ. The relationship between controlled substances and violence. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):5–31.

Lundholm L, Frisell T, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N. Anabolic androgenic steroids and violent offending: confounding by polysubstance abuse among 10,365 general population men. Addiction. 2015;110(1):100–8.

van Amsterdam J, Brunt T, van den Brink W. The adverse health effects of synthetic cannabinoids with emphasis on psychosis-like effects. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(3):254–63.

Clayton HB, Lowry R, Ashley C, Wolkin A, Grant AM. Health risk behaviors with synthetic cannabinoids versus marijuana. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20162675.

Moberg T, Stenbacka M, Tengstrom A, Jonsson EG, Nordstrom P, Jokinen J. Psychiatric and neurological disorders in late adolescence and risk of convictions for violent crime in men. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:299.

Yu R, Geddes JR, Fazel S. Personality disorders, violence, and antisocial behavior: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Personal Disord. 2012;26(5):775–92.

Coid JW, Gonzalez R, Igoumenou A, Zhang T, Yang M, Bebbington P. Personality disorder and violence in the national household population of Britain. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2017;28(5):620–38.

Allen A, Links PS. Aggression in borderline personality disorder: evidence for increased risk and clinical predictors. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(1):62–9.

Gonzalez RA, Igoumenou A, Kallis C, Coid JW. Borderline personality disorder and violence in the UK population: categorical and dimensional trait assessment. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:180.

Fazel S, Doll H, Langstrom N. Mental disorders among adolescents in juvenile detention and correctional facilities: a systematic review and metaregression analysis of 25 surveys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(9):1010–9.

Gaiffas A, Galera C, Mandon V, Bouvard MP. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in young French male prisoners. J Forensic Sci. 2014;59(4):1016–9.

Mohr-Jensen C, Steinhausen HC. A meta-analysis and systematic review of the risks associated with childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on long-term outcome of arrests, convictions, and incarcerations. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;48:32–42.

Lundstrom S, Forsman M, Larsson H, Kerekes N, Serlachius E, Langstrom N, et al. Childhood neurodevelopmental disorders and violent criminality: a sibling control study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(11):2707–16.

King C, Murphy GH. A systematic review of people with autism spectrum disorder and the criminal justice system. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(11):2717–33.

Heeramun R, Magnusson C, Gumpert CH, Granath S, Lundberg M, Dalman C, et al. Autism and convictions for violent crimes: population-based cohort study in Sweden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):491–7.e2.

Witt K, van Dorn R, Fazel S. Risk factors for violence in psychosis: systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 110 studies. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55942.

Large MM, Nielssen O. Violence in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2011;125(2–3):209–20.

Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Rosenheck RA, et al. A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):490–9.

Coid JW, Kallis C, Doyle M, Shaw J, Ullrich S. Shifts in positive and negative psychotic symptoms and anger: effects on violence. Psychol Med. 2018;48(14):2428–38.

McNiel DE, Eisner JP, Binder RL. The relationship between command hallucinations and violence. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(10):1288–92.

Link B, Stueve A, Phelan J. Psychotic symptoms and violent behaviours: probing the components of “threat/control-override” symptoms. J Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33(Suppl 1):S55.

Ullrich S, Keers R, Coid JW. Delusions, anger, and serious violence: new findings from the MacArthur violence risk assessment study. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(5):1174–81.

Coid JW, Ullrich S, Kallis C, Keers R, Barker D, Cowden F, et al. The relationship between delusions and violence: findings from the East London first episode psychosis study. JAMA Psychiat. 2013;70(5):465–71.

Jennings WG, Piquero AR, Reingle JM. On the overlap between victimization and offending: a review of the literature. Aggress Violent Behav. 2012;17(1):16–26.

Silver E. Mental disorder and violent victimization: the mediating role of involvement in conflicted social relationships. Criminology. 2002;40(1):191–212.

Yu R, Branje S, Meeus W, Koot HM, van Lier P, Fazel S. Victimization mediates the longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and violent behaviors in adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2018;46(4):839–48.

Sariaslan A, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Fazel S. Triggers for violent criminality in patients with psychotic disorders. JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73(8):796–803.

Fazel S, Wolf A, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, Mallett S, Fanshawe TR. Identification of low risk of violent crime in severe mental illness with a clinical prediction tool (Oxford Mental Illness and Violence tool [OxMIV]): a derivation and validation study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(6):461–8.

American Psychiatric Association (APA). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2010.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management [CG178]. London: NICE; 2014.

American Psychiatric Association (APA). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2010.

Fazel S, Lichtenstein P, Grann M, Långström N. Risk of violent crime in individuals with epilepsy and traumatic brain injury: a 35-year Swedish population study. PLoS Med. 2011;8(12):e1001150.

Molero Y, Zetterqvist J, Binswanger IA, Hellner C, Larsson H, Fazel S. Medications for alcohol and opioid use disorders and risk of suicidal behavior, accidental overdoses, and crime. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(10):970–8.

Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, Långström N, Larsson H, Fazel S. Association between prescription of major psychotropic medications and violent reoffending after prison release. JAMA. 2016;316(17):1798–807.

Fazel S, Zetterqvist J, Larsson H, Långström N, Lichtenstein P. Antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, and risk of violent crime. Lancet. 2014;384(9949):1206–14.

Frogley C, Taylor D, Dickens G, Picchioni M. A systematic review of the evidence of clozapine’s anti-aggressive effects. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(9):1351–71.

Bhavsar V, Kosidou K, Widman L, Orsini N, Hodsoll J, Dalman C, et al. Clozapine treatment and offending: a within-subject study of patients with psychotic disorders in Sweden. Schizophr Bull. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbz055.

Wolf A, Whiting D, Fazel S. Violence prevention in psychiatry: an umbrella review of interventions in general and forensic psychiatry. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2017;28(5):659–73.

Singh JP, Serper M, Reinharth J, Fazel S. Structured assessment of violence risk in schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders: a systematic review of the validity, reliability, and item content of 10 available instruments. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(5):899–912.

Fazel S, Singh JP, Doll H, Grann M. Use of risk assessment instruments to predict violence and antisocial behaviour in 73 samples involving 24 827 people: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4692.

The Topol Review. Preparing the healthcare workforce to deliver the digital future. Health Education England; 2019.

Berman NC, Stark A, Cooperman A, Wilhelm S, Cohen IG. Effect of patient and therapist factors on suicide risk assessment. Death Stud. 2015;39(7):433–41.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Whiting, D., Fazel, S. (2020). Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Violence in People with Mental Disorders. In: Carpiniello, B., Vita, A., Mencacci, C. (eds) Violence and Mental Disorders. Comprehensive Approach to Psychiatry, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33188-7_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33188-7_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-33187-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-33188-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)