Abstract

Societal inequality is one of the defining issues of our time. The last decade has seen a marked increase in public consciousness around income inequality, in response to both major economic turmoil and a growing body of research that spells out some of the ways in which living in unequal societies does us harm. However, somewhat lacking in this discourse so far is an understanding of the ways in which income inequality changes the psychological underpinnings of our behavior and thereby affects our social lives and the fabric of society. In this chapter, we argue that social psychology has a great deal to offer those who seek this understanding, not only in terms of our theories and capacity to bridge the macro- and micro-levels but also in terms of our methodologies. We also present an overview of the contributions by researchers at the forefront of the application of social psychological approaches to inequality that this volume contains. We finish with a call to action: researching the social psychological processes that drive the effects of inequality is a timely and important endeavor, and is essential if we are to work to achieve a more positive future.

This contribution was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery grant (DP170101008).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

At the moment of writing the introduction to this edited book, the latest Oxfam report on inequality has just been released (Oxfam, 2019). One of the key statistics revealed by the report is that the 26 most wealthy people in the world now own as much as the 3.8 billion poorest people (i.e., half of the world’s population). Moreover, while billionaires saw their wealth increase by 12% in 2018, the 3.8 billion poorest people actually lost 11% of their wealth.

These statistics reflect a troubling reality. As the gap between the world’s poorest and wealthiest has widened, historical progress in combating poverty has largely been undone. In particular, while recent decades had seen a reduction in levels of poverty worldwide due to the concerted efforts of governments and non-government organizations (NGOs) (among others), since 2013 the rate of poverty reduction has halved. This is, in large part, attributed to rising levels of inequality. There are also signs that poverty is becoming more entrenched and pervasive. This brings with it a wide variety of negative outcomes such as high infant mortality, limited access to education, poor healthcare provision and reduced life expectancy. It is also clear that women are the hardest hit by these negative effects of inequality. This is both because women are more often at the poorer end of the wealth spectrum and because in highly unequal societies, relationships between men and women are also more unequal (Oxfam, 2019; see also European Commission, 2018).

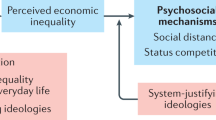

Reflecting the broad recognition that economic inequality is one of the defining social issues of our age, there is a growing body of research that aims to map out its negative effects. However, to date, this work has focused on a somewhat narrow set of outcomes. In particular, most of this work has addressed either the impact of inequality on societies’ economic outcomes (e.g., whether inequality affects economic growth; whether it triggers economic recessions; Kremers, Bovens, Schrijvers, & Went, 2014; Piketty, 2014) or the consequences of inequality for individuals’ health and well-being (see Helliwell & Huang, 2008; Oishi, Kesibir, & Diener, 2011; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). Rather neglected is the impact of (growing) inequality on a society’s social and political life. Furthermore, although there is some initial evidence that growing inequality does fray a society’s social and political fabric—lowering trust and social capital and increasing violence and social unrest (Fajnzylber, Lederman, & Norman, 2002a, 2002b; Tay, 2015; Uslaner & Brown, 2005; for a review, see d’Hombres, Weber, & Leandro, 2012)—this work lacks compelling, theory-driven explanations for why inequality has these effects and when and for whom these effects are likely to emerge. These are important gaps because to respond effectively to inequality, we need a holistic understanding of its effect on individuals as well as on the collectives within which individuals are embedded. In answering these questions, there is an important role for social psychological theorizing because this is ideally suited to develop an understanding of the processes through which inequality can have societal-level effects. Advancing our understanding of the social psychological underpinnings of inequality is a timely and important research endeavor. This edited book aims to be the forefront of this journey.

In the remainder of this chapter, we will first articulate in greater detail how social psychological insights can enhance our understanding of the effects of inequality and the processes that underpin them, before outlining the structure of the book and the chapters that comprise it.

What Can a Social Psychological Analysis Offer?

Existing research on income inequality has yielded a number of important insights. It has also played an important role in raising international awareness of its potential to do substantial harm to nations’ economies and the health and well-being of citizens. At the same time, however, this work has struggled to form a complete and comprehensive picture of the way that inequality affects societies. A social psychological analysis can help to fill the gaps in this picture in at least three ways: (1) by pointing to the processes that explain why inequality has negative effects for individuals and societies, (2) by emphasizing the relevance of subjective perceptions of inequality, and (3) by identifying the group dynamics that underpin the negative effects of inequality. We will explore each of these contributions in more detail below.

Uncovering Underlying Processes

Despite the fact that great progress has been made in understanding the negative effects of inequality on a range of outcomes, it is also clear that these findings are in need of an explanation—reasoning that helps us understand the how and when of the negative effects of inequality. For example, in relation to predicting whether inequality leads to social conflict, Østby (2013) notes: “…the reasoning behind the various propositions—how and why inequality breeds conflict—has typically been lacking” (Østby, 2013, p. 213). Partly as a response to this state of affairs, it has been suggested that (social) psychologists should be involved to a greater extent in this work. For example, in recognition of the important role that psychological processes play in determining responses to inequality, the British epidemiologist Wilkinson recently made the (whimsical) statement that: “to understand the consequences of inequality, it might be more fruitful to study monkeys than Marx” (Kremers et al., 2014, p. 26).

To understand what social psychology can contribute to an understanding of the pathways through which inequality affects outcomes, it is worth considering the discipline’s remit. A generally accepted definition of social psychology is that it is concerned with the scientific study of how people’s thoughts, feelings and behaviors are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others (Allport, 1954). In exploring how human behavior is influenced by other people, social psychologists pay particular attention to the role of the social context, and typically explore this experimentally. Although experimental methodologies can have downsides (including the low external validity of laboratory studies), there are two ways in which they may contribute to a better understanding of the effects of inequality.

First, experiments are able to establish causality. Although the existing body of work on income inequality has shown that there is a relationship between inequality and various outcomes, it has been less successful in determining causality: that is, that inequality causes these various outcomes. This is an important limitation because it leaves open the possibility that the observed relationship between inequality and other outcomes is spurious, and that the causal mechanism is something else entirely. Using experiments to establish causality can also be helpful where the relationships may be bidirectional (e.g., if inequality causes low generalized trust, which in turn increases inequality). While such bidirectionality is not problematic per se, experiments can provide insight into the relative strength of the opposing causal relations, and this can be helpful when exploring ways to address negative effects of inequality (see also Buttrick & Oishi, 2017).

Second, in their use of experiments, social psychologists are well positioned to study the factors that lead us to behave in a given way in the presence of others by systematically unpacking the conditions under which certain thoughts, feelings, and behaviors occur. Specifically, experiments can help us to tease out when particular contexts trigger specific behaviors and outcomes. This means that, even though experimental contexts are often low in external validity, they may help us to isolate important moderating variables and explore their role in the individual and social processes that unfold in the presence of inequality.

Although we are arguing here for the important contribution that an experimental social psychological approach can make to an understanding of the processes through which income inequality has its effects, we hasten to say that experimental research should not come at the expense of other approaches. Indeed, the findings of experiments are most valuable when they corroborate findings that have been obtained in richer and more naturalistic contexts and then extend them by providing insight into causality, moderators, and mediating processes. We are therefore pleased that many of the contributions to this book advance knowledge by drawing from empirical evidence that has been produced using a wide variety of methodologies (including experiments) and from a range of disciplinary perspectives.

Focusing on Subjective Perceptions of Inequality

In many studies to date, the effects of inequality are examined by focusing on objective indicators, based on collated administrative data (such as the Gini index). Even though these efforts are important, they rest on the assumption that changes in actual income inequality in a country or society are tightly coupled with citizens’ perceptions of and reactions to this inequality. That is, this work assumes that if inequality is large, people will perceive it as such. There is a small (but growing) body of research that identifies a number of problems with this assumption. For example, longitudinal research in China and Japan has shown that changes in objective income inequality do not systematically translate into changes in people’s perceptions of income inequality or their evaluations of it (Tay, 2015). Recent history provides further evidence of the loose association between objective and subjective inequality. Despite the fact that objective levels of inequality were rather high before the onset of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, public awareness of this was low. It was only in the aftermath of GFC, when collectively shared narratives of inequality took hold, that people’s awareness increased. These collectively shared perceptions were instrumental in shaping the collective action and protest that followed the GFC (e.g., the Occupy movement). It is, therefore, imperative that researchers do not restrict themselves to an examination of actual levels of inequality (e.g., changes in the Gini coefficient over time) but consider subjective perceptions too.

To the extent that people’s responses to inequality are a function of their perceptions, the potential contribution of social psychological theorizing again becomes clear. Social psychology has a rich literature explaining why people perceive the world the way they do and how they then respond to those perceptions. In the context of inequality, people’s perceptions and responses can be expected to be influenced by a range of social psychological processes that relate to inequality between individuals and groups, including social comparisons, relative deprivation, fairness perceptions, social identity considerations, power relations, and ideological stances. By engaging with these processes, we can ask new and revealing questions. When will people have accurate perceptions of a society’s inequality and under what conditions will high levels of inequality remain undetected? Who will be most likely to perceive the inequality that exists, and who will not? And when will perceptions that society is unequal be accompanied by beliefs that this is problematic? Contributing to a better understanding of questions like this, many of the contributions to this book focus on subjective income inequality—people’s perception of income inequality in a particular social context.

From Inequality Between Individuals to Inequality Between Groups

The third potential role that social psychology can play in advancing our understanding of the effects of inequality relates to its ability to elucidate the role of group dynamics. The importance of examining group dynamics is powerfully demonstrated by Østby’s (2013) analysis of the relationship between inequality and political violence. After reviewing the research in this area, Østby observed that when measures pertain exclusively to individual differences in income, there is little empirical support for a relationship between inequality and political violence. However, when examining studies that focus on group inequality, the picture is quite different. In particular, there is a clear relationship between higher levels of group inequality and greater levels of political violence. Østby argues that this reflects the fact that political violence is typically intergroup, in that politically motivated collective action is motivated by group-level grievances and group identities (see the relative deprivation literature for a similar point; Walker & Smith, 2002). As Østby puts it: “My first conceptual objection is that, in the inequality–conflict literature, most attention has been focused on inequality between individuals. However, the topic of interest, violent conflict, is a group phenomenon, not situations of individuals randomly committing violence against each other” (Østby, 2013, p. 213). In other words, to understand many of the negative consequences of inequality, we need theorizing that allows us to understand when people act as group members.

Social psychology is well positioned to provide this understanding. This is because social psychology—with its focus on the broader socio-structural context as well as group- and individual-level behavior—spans sociology and psychology. Accordingly, it is ideally suited to speaking to the way that macro-level features (e.g., societal inequality) have consequences for groups at the meso-level and individuals at the micro-level. Some of the authors to this contribution argue that the Social Identity Approach—SIA, composed of social identity theory (SIT; Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and self-categorization theory (SCT; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987)—is a particularly useful theoretical framework for articulating the way that these different levels connect and interact to influence behavior (see also Jetten et al. 2017). This is because the SIA provides explicit theorizing about how individual-level psychological processes are affected and informed by the broader socio-structural context (e.g., economic and political factors affecting status relations between groups).

What is more, engaging with societal inequality allows for the elaboration and extension of social psychological theorizing. Indeed, this newly emerging area of inquiry is providing a novel testing ground for social identity theorizing in particular. In the process, it both contributes to an already-established literature on intergroup threat, group dynamics, procedural justice, stereotyping, and prejudice, while simultaneously breaking new theoretical ground. This edited book brings together researchers who are all well-versed in theorizing relating to group processes, social identity, and intergroup relations. Their contributions hold the promise of real theoretical and empirical progress.

As-yet Untapped Social Psychological Potential

We have argued that social psychology has a great deal to offer to those who wish to understand the effects of income inequality and, as a consequence, those who wish to intervene to ameliorate these effects or to understand barriers to the pursuit of greater equality. However, to date, this potential is largely untapped. To illustrate this, we used Google Search to examine the number of articles published between 1990 and 2018 that mentioned “income inequality” in their title, while also referring to “social psychology” in any field. As Fig. 1 shows, there has been a promising increase in the number of articles that refer to incomeinequalityand social psychology in the last decade. So, while fewer than 20 such articles were published each year before 2009, in the last 10 years this number has steadily increased, climbing to 54 in 2018.

However, it is important to put this growth into perspective. Figure 2 additionally graphs the number of articles that mentioned “income inequality” in their title but did not refer to “social psychology” in any field. Here too, it is obvious that there has been a tremendous increase in the number of published articles. More importantly, this increase is such that the ratio of articles on income inequality that engage with social psychological theorizing has not changed over the last decades. Even though this is only a snapshot analysis, it does suggest that the uptake of social psychological insights remains rather limited and that the potential is unrealized.

This edited book represents an effort to change this state of affairs. For social psychologists to be heard by those who wish to understand societal inequality and to grapple with its effects, we need to more clearly articulate what we have to offer. By bringing together the advances of the foremost scholars of the application of social psychology to inequality, we aim to show how this approach makes a coherent and powerful contribution to our understanding of one of the most pressing social issues of the day and point towards levers for achieving (and barriers to) positive social change.

The Present Book

The aim of this book is to bring together researchers who have been at the forefront of a social psychological analysis of economic inequality. By taking stock of these insights and by bringing them together in one volume, we hope to generate a valuable resource that captures the state of the field. It is our belief that these contributions will help us to build a research agenda that moves the field forward. The contributions are not only indicative of the excellent work that is being done but also serve to showcase the full range of questions and contexts and approaches in this field. This can be seen in our decision to include contributions by researchers who may not necessarily define themselves as social psychologists, but who have conducted research that we believe is of utmost relevance to social psychologists. It can also be seen in the different forms of inequality that are explored in this book (ranging from inequality in wealth to that which accompanies gender and social class). And, it can be seen in the international perspectives that are present among the contributors, who are based in 13 different countries.

Although, as noted previously, not all contributions focus on income inequality, most of them do. Economic or incomeinequality has traditionally been the purview of economists, political scientists, epidemiologists, and sociologists, and these researchers have mostly focused on objective indicators of inequality. The most frequently used of these is the Gini coefficient, which captures a society’s position on a scale that ranges from 0 (perfect equality: all individuals have equal wealth and income) to 1 (perfect inequality: one individual has all of the wealth and income). Other indicators are also possible though, including those that calculate the ratio in earnings between those at the top and those at the bottom of the income distribution.

Our book also engages with inequality more broadly by including contributions that focus on inequality associated with gender (e.g., the gender pay gap) and social class (the form of economic inequality that has attracted the most interest from social psychologists to date). Even though social psychologists have always been interested in individual- or group-level differences in terms of social status, voice, power, and influence (e.g., as determined by, e.g., ethnicity or gender), only in recent years have they started to systematically explore the effects of economic inequality, largely in terms of social class (see Fiske & Markus, 2012; Manstead, 2018). This research has revealed that those at the lower and upper ends of the social class spectrum effectively live in different worlds, and that these differences have psychologically important outcomes, affecting stereotypes, values, and goals (see Stephens, Markus, & Phillips, 2014).

Reflecting this body of work, many of the chapters in this book focus on social class and the array of cultural and social dimensions that tend to co-occur with it (Manstead, 2018). However, an analysis of the effects of economic inequality cannot be reduced to an analysis of social class. This is because the consequences of inequality not only are due to the existence of high and low classes but also depend on the size of the gap and the distribution of economic resources (e.g., the lower versus the higher tail of the distribution). In order to integrate these insights, contributors who talk about social class have also considered how an unequal context may affect how social class matters.

In what follows, we provide a brief overview of the 23 contributions to this edited book. These contributions fall into five themes that examine the psychological and behavioral consequences of inequality in a range of different contexts and unpack the psychological processes that produce these effects and that maintain unequal systems. The first two themes explore the consequences of inequality in organizational (Section 1) and educational settings (Section 2), and the third includes contributions that focus on impact of inequality for a range of important behaviors including food intake, consumption, prosocial behavior, risk taking, and decision-making (Section 3). The fourth theme includes contributions that shed light on the processes that underlie the negative effects of inequality and the fifth theme includes contributions that focus on why and how inequality is maintained.

Section 1: Inequality in Organizational Contexts

In this section, we bring together contributions that have explored the various consequences of inequality in organizational settings. Although organizations play an important role in producing societal inequality and are unequal contexts in their own right, it is only more recently that researchers have started to focus on the (social) psychological effects of organizational inequality. Together, these chapters suggest that many important negative consequences of inequality manifest in organizational contexts and that organizational processes present barriers and potential solutions to positive societal change. Accordingly, it is important that future work pays greater attention to the context where a substantial portion of society lives out their daily lives.

The first contribution by Kim Peters, Miguel Fonseca, Alexander Haslam, Niklas Steffens, and John Quiggin focuses on the consequences of excessive CEO pay for employees’ reactions to these CEOs. In particular, and contrary to traditional perspectives that suggest that high CEO pay is beneficial for organizations (and society), they present evidence that high CEO pay may make it harder for CEOs to effectively lead other members of their organizations. In particular, they show that employees are less likely to personally identify with highly paid CEOs (compared with more moderately paid CEOs) and that this, in turn, reduces their perceptions that the CEO is an effective and charismatic leader. Ironically then, in the eyes of employees, high pay is not a cue that the leader must be extraordinary competent, but rather directly impairs the perception that the CEO has the capacity to lead their organization.

The next chapter by Clara Kulich and Marion Chipeaux focuses on economic gender equality and the psychological mechanisms that produce unequal economic outcomes for women and men in the workplace. The authors highlight a range of social causes of these unequal economic outcomes that are in large part responsible for the fact that women have less than 60% of the economic power of men, including gender stereotypes that lead to biased hiring decisions, occupational segregation and the devaluation of “women’s work,” and differences in men’s and women’s responses to organizational inequality. Importantly, the authors argue that to address gender inequality, it will be necessary for organizations to adopt structural changes that ensure equal promotion and remuneration conditions for men and women and that create supportive organizational climates and transparency in terms of the way resources are divided.

Next, Lixin Jiang and Tahira Probst outline the way that income inequality in society more broadly negatively affects people’s ability to cope with work-related stressors. They focus on two processes that can explain this relationship. First, high-income disparity directly increases employee stress because income inequality promotes the adoption of structural conditions that threaten the work and financial conditions of employees (e.g., fewer employment protections, shorter duration of unemployment benefits, and lower union density). Second, high-income inequality may reduce employees’ abilities to cope with these stressors because it has been shown to erode people’s ability to access resources that can buffer against stress (including trust) and undermine group cohesion in society. Rather ironically then, employees are facing two challenges as a result of high-income disparity: poor objective conditions and a weakening in the social fabric that people rely on to cope with such conditions.

The final chapter in this section by Boyka Bratanova, Juliette Summers, Shuting Liu, and Christin-Melanie Vauclair explores how the capacity of societal inequality to increase interpersonal competition and social comparisons heightens status seeking and the pursuit of self-esteem. In the context of organizations, such dynamics can be harmful for employees who internalize a belief that they will get ahead if they only work hard enough, leading to longer working hours and poorer health and well-being. However, Bratanova and colleagues emphasize how organizations may actually hold the key to alleviating some of these negative dynamics (and improving organizational functioning) if they institute more democratic work structures, like employee ownership models.

Section 2: Inequality in Educational Contexts

The second section focuses on the effects of inequality in educational settings such as schools and universities. These contributions reveal that students’ social class matters a great deal for their comfort in educational settings, ability to integrate into them and to achieve high levels of performance. Furthermore, these effects of social class are likely to be exacerbated in more unequal societies. Together, then, these contributions show that the institutions that are meant to help people to break free from their backgrounds may actually perpetuate existing class-based structures.

The first contribution by Mark Rubin, Olivia Evans, and Romany McGuffog focuses on the Australian context and explores how inequality in terms of social class differences affects social integration at university. They review research findings that consistently show that lower class students’ integration at universities is lower than that of their higher social class counterparts. And the very fact that these lower class students feel less at home and feel they do not belong at universities negatively impacts on not only their performance but also their health and well-being. To break the negative integration-performance cycle, the authors focus on interventions that enhance integration among lower class students.

Matthew Easterbrook, Ian Hadden, and Marlon Nieuwenhuis take this message one step further and unpack the social and cultural factors as well as the social identity processes that underpin low integration among lower class students at universities. In their Identities-in-Context Model of Educational Inequalities, they focus, in particular, on key social and cultural factors that produce inequalities between social classes in terms of (1) the prevalence of negative stereotypes and expectations about a group’s educational performance, (2) the representation of the group within education, and (3) the group’s disposition towards education. They present evidence that on all three factors, lower social classes typically fare worse than their higher social class counterparts. Given that these social and cultural factors trigger social identity threat and perceptions of identity incompatibility (i.e., “people like me don’t belong at university”), one can explain why lower social class students have poorer performance, lower aspirations, and more negative self-beliefs than higher social class students.

The last two contributions in this section focus not only on perceptions of low versus high social class students, but also on the way the educational system is set up to maintain and even reproduce social inequalities in schools and universities. In particular, Anatolia Batruch, Frédérique Autin, and Fabrizio Butera present evidence that despite the fact that educational systems aim to create contexts where everyone has equal opportunities (meritocracy), structural features introduced to select students have the unfortunate consequence that educational systems do not tackle but reinforce inherent social class inequalities. As a result, educational context may not fulfil the promise of providing a social mobility pathway for all students because social class inequalities are maintained and reproduced.

The authors of the last contribution in this section—Jean-Claude Croizet, Frédérique Autin, Sébastien Goudeau, Medhi Marot, and Mathias Millet—put forward a similar analysis and conclusion. Drawing from sociological theorizing, they also focus on the processes that explain how social inequality between the social classes is maintained and perpetuated. These authors show how educational systems institutionalize an essentialist classification of students whereby social comparisons lead to the sorting of students in groups of “those that belong here” and “those that do not belong here.” Because this process is subtle and part of educational practices aimed at enhancing learning, the processes that perpetuate inequalities are not noticed and therefore not challenged. As a result, unfortunately, educational systems play an important role in the reproduction and legitimation of the existing (unequal) social structure.

Section 3: Consequences of Inequality on Preferences and Behaviors

While the first two sections focus on contexts within which many people spend the majority of their waking hours across the lifespan, there are many important behaviors that occur outside of educational and organizational institutions or that are not specifically tied to them. This third section pulls together contributions that show the wide variety of such behaviors that are affected by social inequality and that can account for many of inequality’s negative consequences, such as poor health and social outcomes. More specifically, these chapters show how societal inequality can have an impact on people’s consumption of food and other material goods, self-sexualization, prosocial behavior, and risk-taking.

Almudena Claassen, Olivier Corneille, and Olivier Klein focus on the relationship between inequality and food intake. Starting with the observation that societies with higher levels of economic inequality have higher obesity rates, the authors ask the question why that would be the case. While it is likely that there are multiple processes at work, Claassen and colleagues focus on evidence that inequality triggers perceptions that the environment is a harsh one necessitating competition for scarce resources. This perception of scarcity increases the desire for highly caloric food. They also discuss the possibility that inequality increases the salience of status differences, which encourages social comparisons and conformity to social class norms concerning specific food consumption. These processes too can be expected to lead to higher food consumption.

Khandis Blake and Robert Brooke also focus on the way that economic inequality enhances social competitiveness and a concern about status, but make the important point that these may, at times, have different implications for men and women. In particular, whereas men are more likely to engage in behaviors that enhance their social status in unequal than in more equal contexts (even if this means engaging in dangerous and violent behaviors), women are more likely to socially compete by enhancing their competitive reproductive pursuits. In particular, assessing the number of “sexy selfies” posted on online social network sites such Twitter and Instagram across 113 countries, Blake and Brooke found that in areas of higher income inequality, women posted more sexy selfies online. This suggests that when inequality is higher, women feel a greater need to show their attractiveness to the world as a status enhancement strategy.

In the third contribution of this section, Kelly Kirkland, Jolanda Jetten, and Mark Nielsen focus on the way that children respond to inequality. These authors start with an outline of the way that children understand fairness and focus on at what time in their development children’s prosocial behavior is guided by concerns about equity, merit and need. In the second part of this contribution, the authors focus more explicitly on inequality in the social context and they provide evidence that children as young as 4 years old are less prosocial when it comes to sharing resources with another child when they find themselves in a context of high compared to low inequality. As the authors note, these findings are important in helping us to develop an understanding of fundamental human responses to inequality and how (and when) living in unequal societies can influence human prosociality.

The next contribution by Jazmin Brown-Iannuzzi and Stephanie McKee focuses on the effect of inequality on risk-taking behaviors. The authors argue that to understand the effects of societal inequality, it is necessary to examine subjective (in addition to objective) inequality, because these subjective experiences and perceptions influence the extent to which individuals engage in upward social comparisons. The authors review empirical evidence (including their own work) that shows that when people perceive that they are living in an unequal society, they are more willing to take risks and exhibit greater greed. To explain these relationships, they combine predictions from social comparisons and risk sensitivity theorizing and argue that economic inequality triggers upward social comparisons, further enhancing socially competitive behaviors. Risk is then taken to meet higher perceived need.

In the final chapter in this section, Jennifer Sheehy-Skeffington focuses on the consequences of being poor on decision-making. She makes a compelling case that inequality enhances perceptions of being poor, which enhances perceptions of socio-economic threat. This, in turn, is associated with suboptimal decision-making such as risk taking, gambling, and spending a greater proportion of income on luxury goods—all behaviors that enhance financial strain and debt. However, rather than viewing these behaviors through a cognitive deficit lens, Sheehy-Skeffington argues that these behaviors can be considered adaptive. In particular, risky and short-term decision-making may well serve the important proximal goal of surviving in the harsh context that inequality represents.

Section 4: Why Does Inequality Have These Negative Outcomes?

While authors in the preceding sections have evoked a range of psychological mechanisms in the course of examining the various effects of income inequality, this fourth section brings together contributions that are specifically concerned with explaining some of the ways in which inequality affects basic psychological processes and motivations. In particular, these contributions show that inequality can spark social anxiety and threat, can lead to misperceptions of one’s position in society relative to others, can fuel a desire for more and can affect people’s awareness of class divides in society.

Lukasz Walasek and Gordon Brown start this section and, in their contribution, they review the social rank and material rank hypotheses and explain how these processes are crucial in understanding the negative effects of inequality on a range of outcomes. The authors start with a critical analysis of the social anxiety hypothesis—the idea that inequality enhances social comparison and social status concerns, which is reflected in a heightened interest of people in positional goods when inequality is higher. In an attempt to pinpoint more precisely the cognitive underpinnings of the negative effects of inequality on social outcomes, they propose to engage with models that are developed in the decision-making literature and then in particular rank-based cognitive models. In support of their argument, the authors show how these models can help to understand why it is not income but the relative ranked position of people’s income within a social comparison group that best predicts the negative effects of inequality.

Danny Osborne, Efraín García-Sánchez, and Chris Sibley propose the Macro–micro model of Inequality and RElative Deprivation (MIRED), which focuses, in particular, on the way that relative deprivation perceptions are crucial in explaining the negative effects of inequality on outcomes. In particular, they propose that inequality heightens people’s perceptions that they are deprived (either as individuals or as a group). They note that even though the negative well-being effects of such relative deprivation perceptions are well documented, it is clear that inequality-induced relative deprivation also has other outcomes. In particular, it heightens the extent to which people identify with their ethnic group. It is important to understand these processes, because heightened ethnic identification may motivate tensions between groups and heighten “us” versus “them” perceptions and, at times, this will lead to collective action and social unrest.

In the next contribution, Daan Scheepers and Naomi Ellemers make the important point that inequality may at times also be threatening for high-status groups. In particular when the unequal status and access to resources are perceived as illegitimate and likely to change in the future (i.e., status relations are unstable), high-status groups may perceive that their status is under threat and this causes status stress. Scheepers and Ellemers present a number of studies that provide neurophysiological evidence for status stress among high-status groups that worry about shifting power relations between status groups. In recognition that attempts to address status stress may backfire, the authors finish their contribution with a number of useful interventions that one can employ to reduce defensive reactions from high-status groups when attempting to alleviate high levels of inequality.

The next contribution by Zhechen Wang, Jolanda Jetten, and Niklas Steffens focuses not so much on the fear of groups that they might lose status in unequal status systems, but on the question how inequality affects the desire for more money and status. The authors present empirical evidence that the desire for more money and status is higher in unequal than in more equal societies. In addition, they find that this desire is higher among those who find themselves at the poorer end of the wealth spectrum compared with their wealthier counterparts. The authors finish with the point that to better understand these dynamics, it is important to take account of the fact that the broader socio-structural contexts moderate and shape these responses. They present an outline of social identity theory predictions focusing on the feasibility to achieve upward mobility in an unequal society, and the stability and legitimacy of existing levels of inequality to better be able to predict responses to inequality.

In the final contribution to this section, Héctor Carvacho and Belén Álvarez raise the interesting point that inequality may not be noticed, and, that for it to be noticed, people need to develop a sense of class consciousness. Starting with the observation that despite the fact that inequality is harmful for the working classes in the sense that it puts a spotlight on their disadvantage, working classes (i.e., low-status groups) are remarkably accepting of inequality and do not seem to routinely challenge it. The authors present compelling evidence not only that class consciousness is higher in countries that are more economically unequal, but also that class consciousness is detrimental for working-class individuals’ health and life satisfaction. This poses interesting questions about the health consequences of noticing versus being blind to inequality.

Section 5: Why and How Is Inequality Maintained?

There is good evidence that inequality is bad for everyone (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009)—although it may be worse for some than for others. But, when it comes to reducing inequality in a society, it is likely that the motivation to tackle inequality differs across different groups (e.g., the wealthy, middle-class and the poor, those at the political left versus those at the political right, those who have more versus less formal education). Addressing inequality therefore relies on an understanding of how to overcome the resistance of some. It also relies on an understanding of the rhetorical and explanatory constructs that allow people to justify and seek to perpetuate or increase inequality. The chapters in this last section bring together contributions that aim to improve this understanding, and thereby point to important levers for those who seek to bring about change.

A first contribution by Martha Augoustinos and Peta Callaghan sheds light on the way that language is used and employed to maintain and justify inequality. The authors note that despite the sustained attention social inequality has received in Western liberal economies by public policy experts, there has been little research examining how ordinary people talk about social inequality in everyday life. This chapter examines the language of inequality and how it is articulated in everyday talk and social interaction. Drawing on research examining talk about racial, gender and economic concerns, the authors show how the language of inequality is patterned by the flexible use of contradictory liberal egalitarian principles. Through the flexible deployment of these principles, social inequality is typically rationalized and justified, particularly but not exclusively by members of dominant groups. In general, these strategies function to justify existing social inequalities and deny the need for social change.

The next chapter by Susan Fiske and Federica Durante focuses on the important role of mutual status stereotypes in maintaining inequality. They note that inequality creates mutual resentments and this forms a fertile ground for mutual stereotypes to become more negative. Social psychology survey data from the stereotype content model (SCM)describe images of arrogant elites, who seem competent but cold. In addition, the working class is depicted as incompetent (as hillbillies, rednecks, or simply ignorant). The authors note how mixed and more ambivalent stereotypes prevail in more unequal societies and further serve to maintain and justify the system. To break this cycle, structural change is required, which focuses for elites on interpersonal solutions (e.g., acknowledging inequality) and for blue-collar individuals, reconciliation may require more structural solutions.

In the next section, John Blanchar and Scott Eidelman focus on yet another way in which inequality is maintained and justified by emphasizing the longevity of systems of inequality. They present research that shows that the longer the prevailing social arrangements are in place, the more they are perceived as the natural and fair way to organize society. Because people justify the status quo when systems are long-standing, it is relatively rare that they will challenge these systems—they were found to experience less moral outrage and therefore less support for social change—contributing to their continued existence. To reverse the influence of system longevity on the legitimation of inequality, it would be essential to draw attention to inequality. However, this would require motivation and mental effort to consider the unfairness of existing forms of inequality.

The notion that fairness perceptions are key to challenging existing inequality also comes to the fore in the next contribution by Martin Day and Susan Fiske. These authors focus on the nature and consequences of social mobility beliefs and argue that perceptions that it is relatively easy to climb the social and economic ladder represent a double-edged sword. At least at the societal level, collectively shared perceptions that “one can make it if one tries” justifies the status quo and justifies existing inequalities. At the personal level, effects of the belief in social mobility are less straightforward and such a belief can be either a motivating force for individuals or one that undermines their well-being. The authors outline a number of avenues for future research that might shed greater light on the role of social mobility beliefs in the maintenance of inequality.

The final contribution to this section (and also this book) by Rael Dawtry, Robbie Sutton, and Chris Sibley focuses on the way that perceptions of wealth distributions are key in predicting support for the redistribution of wealth to alleviate negative effects of inequality. In contrast to research that has shown that resistance to wealth distribution is a motivated response (i.e., those who are wealthier may oppose redistribution out of self-interest), these authors nicely point out that perception also plays a key role in such resistance. In particular, they show how wealthier segments of society are also typically exclusively exposed to people of similar wealth. In turn, this means that wealthy people overestimate societies’ wealth and they therefore do not perceive there to be much of a need for redistribution through social policy.

Charting a Course to a More Equal Future

It may seem that, by finishing with a series of contributions that deal with the forces that maintain social inequality, this book ends on a rather gloomy note. However, in our view at least, all is not doomed and indeed there are a few developments that are a source of hope. This endeavor of bringing together the social psychological knowledge on inequality is occurring in a context where the outcry over the high levels of inequality seems to be growing stronger. For example, as we write, the media is reporting an increased appetite among American voters to increase taxes on the super wealthy to address rising levels of inequality. This can be seen in recent headlines such as “Most Americans support increasing taxes on the wealthy,” “A 70% tax on the super-rich is more popular than Trump’s tax cuts, new poll shows,” and “nearly half of Americans support Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s 70% marginal tax on the super-rich, according to a new poll.” Of course, the willingness to address inequality by supporting drastic measures may be short-lived and ultimately lies in the hands of those with the levers of power; but still, there is hope.

And although there is not much we can do about current political developments, we believe that a positive future requires a solid platform of knowledge about the phenomenon of social inequality. And while the contributions in this book largely identify how and why inequality does us harm, and is so hard to counter, we can foresee a future where a growth in the body of work that applies social psychological approaches to these problems will enable a sequel providing a social psychological analysis of the effectiveness of the different interventions that aim to address and alleviate the negative consequences of inequality. To bring about this future, we hope that this book inspires researchers to not merely accept the situation as they find it but to think of how they can work towards producing social outcomes that are beneficial for all of us. Although the challenges are great, many of the most important tools (i.e., rigorous theorizing and empirical work) are within our hands. We hope that you, the reader, are willing to be part of this journey.

References

Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books.

Buttrick, N. R., & Oishi, S. (2017). The psychological consequences of income inequality. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11, e12304.

d’Hombres, B., Weber, A., & Leandro, E. (2012). Literature review on income inequality and the effects on social outcomes. Reference Report by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission.

European Commission. (2018). Report on gender equality between women and men in the EU. doi: https://doi.org/10.2838/168837

Fajnzylber, P., Lederman, D., & Norman, L. (2002a). What causes violent crime? European Economic Review, 46(7), 1323–1357.

Fajnzylber, P., Lederman, D., & Norman, L. (2002b). Inequality and violent crime. Journal of Law and Economics, 45(1), 1–40.

Fiske, S. T., & Markus, H. R. (2012). Facing social class: How societal rank influences interaction. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2008). How’s your government? International evidence linking good government and well-being. British Journal of Political Science, 38, 595–619.

Jetten, J., Wang, Z., Steffens, N. K., Mols, F., Peters, K., & Verkuyten, M. (2017). A social identity analysis of responses to economic inequality. Current Opinion in Psychology, 18, 1–5.

Kremers, M., Bovens, M., Schrijvers, E., & Went, R. (2014). Hoe ongelijk is Nederland? Report from the Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Manstead, A. S. R. (2018). The psychology of social class: How socioeconomic status impacts thought, feelings, and behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57, 267–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12251

Oishi, S., Kesibir, S., & Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science, 22(9), 1095–1100.

Oxfam. (2019). Public good or private wealth. Downloaded from https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620599/bp-public-good-or-private-wealth-210119-en.pdf.

Østby, G. (2013). Inequality and political violence: A review of the literature. International Area Studies Review, 16, 206–231.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Stephens, N. M., Markus, H. R., & Phillips, L. T. (2014). Social class culture cycles: How three gateway contexts shape selves and fuel inequality. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 611–634. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115143

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–48). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Tay, S. (2015). Rethinking income inequality in Japan and China (1995-2007): The objective and subjective dimensions. China Report, 51, 230–257.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Uslaner, E. M., & Brown, M. (2005). Inequality, trust, and civic engagement. American Politics Research, 33, 868–854.

Walker, I., & Smith, H. J. (2002). Relative deprivation: Specification, development, and integration. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2009). The spirit level: Why more equal societies almost always do better. London: Penguin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jetten, J., Peters, K. (2019). Putting a Social Psychological Spotlight on Economic Inequality. In: Jetten, J., Peters, K. (eds) The Social Psychology of Inequality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28856-3_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28856-3_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-28855-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-28856-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)