Abstract

Bovine tuberculosis (BTB) and zoonotic tuberculosis (zTB) caused by Mycobacterium bovis remain global problems, and the diseases are a threat to the health and welfare of humans, livestock, and wildlife. It is estimated that 28% of all cases of human TB, a proportion of which is caused by M. bovis, occurs in Africa, and this may be an underestimation of the number of cases. This situation prevails because of the poor diagnostics and limited data available on BTB in most of the African countries because of the lack of human and financial resources and of the will of politicians to implement BTB and zoonotic TB control programs. Data about the prevalence of zoonotic TB are equally scant and incomplete due to the poor diagnostic capacity and lack of surveillance for the disease, and the actual number of cases may exceed current estimates by far. Zoonotic TB may be far more prevalent than expected because of the extensive consumption of raw milk and cohabitation with cattle and other livestock that carry the infection. The ability in Africa to control both BTB and zBT is hampered by numerous factors including the presence of an increasing number of wildlife maintenance hosts of M. bovis that complicates controlling the disease even further. To deal with the threat of the diseases, and to be aligned with the international objectives of globally eradicating human and animal TB, African authorities will have to take concrete steps to do so. Their activities should be based on the principles of One Health that promote an integrated multidisciplinary approach with intergovernmental collaboration and global support, strengthened by joint medical and veterinary training programs, private–public partnerships, awareness programs, and focused research. These matters are discussed in this chapter.

Author “Thoen” was deceased at the time of publication.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

For over 100 years, since Robert Koch discovered the causative agent in 1882, human tuberculosis (TB) caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains a major global public health threat. In recent times, the problem posed by bovine TB (BTB) became of increasing concern to public health officials. Mycobacterium bovis, of which cattle is the primary maintenance host, is not easily differentiated from M. tuberculosis, as both species belong to the genetically related M. tuberculosis complex (MTC) (Brosh et al. 2002). What is more concerning is that M. bovis also infects humans, particularly those who consume unpasteurized dairy products and live in close contact with infected cattle (Cosivi et al. 1998; Thoen et al. 2009), hence the challenge of zoonotic TB (zTB). Mycobacterium bovis was hitherto believed to be transmitted only from cattle to humans (Ayele et al. 2004), but cases of human-to-human transmission via the pulmonary route have been reported recently (Gibson et al. 2004; LoBue et al. 2004; Evans et al. 2007; Thoen and LoBue 2007; Sunder et al. 2009; Etchechoury et al. 2010; Godreuil et al. 2010; Adesokan et al. 2012; Torres-Gonzalez et al. 2013).

The persistence of M. bovis at various prevalences in cattle in countries, such as in Mexico (13.8%) (Perez-Guerrero et al. 2008), Uganda (7%) (Oloya et al. 2008), Nigeria (5%) (Cadmus et al. 2006), the UK (0.17–0.5%) (Stone et al. 2012), France (0.5–2%) (Mignard et al. 2006), The Netherlands (1.4%) (Majoor et al. 2011), and most African countries where dairy products are generally not pasteurized or heat-treated, creates ongoing challenges to prevent zoonotic TB. Significantly, M. bovis infection has recently been categorized as an important neglected disease, affecting the livelihoods mostly of poor and marginalized communities, with increasing zoonotic implications (Hlavsa et al. 2008; Rodwell et al. 2008) and with serious ecological implications as the infection spreads between livestock, wildlife, and humans at the interface between them (Kriek 2014).

2 Bovine TB in Wildlife and Other Animals in Africa

Cattle are known to be the primary maintenance hosts of M. bovis (Brosh et al. 2002; Thoen et al. 2009), but certain species of wildlife are also maintenance hosts of this pathogen (Radunz 2006; Smith et al. 2006; Porphyre et al. 2008; Thoen et al. 2009). Essentially, the brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula), European badger (Meles meles), American bison (Bison bison), African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), Kafue lechwe (Kobus leche kafuensis), and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) are known maintenance hosts of M. bovis in the various countries of the world where they occur (De Lisle et al. 2002; Renwick et al. 2007). In some parts of Africa, particularly in Southern and Eastern Africa, several wildlife species have been identified as reservoirs of M. bovis at the livestock–wildlife interface (Michel et al. 2006). In Africa, African buffaloes and the Kafue lechwe are the primary wildlife maintenance hosts for M. bovis, but there are indications that a number of other species may also be able to sustain the infection (Michel et al. 2006; Renwick et al. 2007; Moiane et al. 2014). (For more information about BTB in wildlife, refer to Chap. 5.) Due to limited studies, and the lack of funding for BTB research and surveillance in wildlife, very scant information exists about the extent of the infection in African wildlife, the importance of wildlife reservoirs in Africa, and the role that they play in the epidemiology of the disease. Much of the available data deal with the situation in Southern and Eastern Africa because of the impact of BTB at the interface on wildlife–ecotourism and conservation in these areas. Bovine TB in wild animals has an impact on wildlife conservation, livestock production, public health, and the burgeoning, lucrative private game ranching enterprises in Southern Africa in particular (de Garine-Wichatitsky et al. 2013).

In Africa, other domesticated animals such as sheep (Houlihan et al. 2008; Mendoza et al. 2012), goats (Daniel et al. 2009; Hiko and Agga 2011; Naima et al. 2011), and camels (Kudi et al. 2012) have also been identified to play a significant role in certain countries in the transmission of M. bovis because of their very close interaction with cattle and joint cattle herding and management practices causing intermingling of these species.

Because of the largely unknown but increasing role that wildlife play in sustaining and transmitting BTB at the human–livestock–wildlife interface, it is important to adopt a holistic approach that includes wildlife populations when tackling the control and eventual eradication of BTB and zTB in Africa. This is critical given the close contact between wildlife and livestock populations in many areas and the known bi-directional transmission of BTB at the interface (Miller et al. 2007; Munyeme et al. 2008; Siembieda et al. 2011; Gortázar et al. 2012; Palmer et al. 2012; Kaneene et al. 2014a). In Africa the forced close interaction between wildlife and cattle, and sometimes humans, who enhance transmission of M. bovis, is the consequence of the scarce and limited water sources that they have to share.

3 Zoonotic BTB: Global Realities and Facts from the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO), in conjunction with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, previously recommended that the epidemiological data pertaining to human TB caused by M. bovis infections, particularly in populations at risk (e.g., livestock workers, veterinarians, hunters, and zoo workers) (WHO-FAO 1994), be collected. The African countries, unfortunately, did not respond to this request, and the information about the disease on the continent remains piecemeal and anecdotal (AU-IBAR 2013). Based on the available raw and incomplete data, Müller et al. (2013) estimated that in Africa there would be 7 zTB cases/100,000 population/year, caused by infection with M. bovis, which is approximately 1% of the total human TB burden. More recently, in 2015, the WHO estimated that 149,000 cases of M. bovis zTB with a mortality of 13,400 occurred globally (WHO 2015a) and that of these 76,300 cases and 10,000 deaths were expected to occur in Africa (WHO 2016a). They considered these figures to be an underestimation given the absence of routine reporting of the disease in most countries in Africa in which BTB is endemic.

The degree of under-investigation, and the likely underestimation of the number of zTB cases in Africa and in some of the other developing countries, implies that the actual number of human zoonotic BTB cases remains unknown but that it may be substantially more than the current estimate (Perez-Lago et al. 2014). With the persistence of M. bovis in cattle in most African countries (Cadmus et al. 2006; Perez-Guerrero et al. 2008; Oloya et al. 2008; Jenkins et al. 2011; Egbe et al. 2016) in association with the general poor standards of living and hygiene, there is a risk that zoonotic BTB will not remain an African problem but that it may become a global health threat (see also Chap. 3).

The increasing emphasis on addressing these issues is largely due to the attention that zTB received globally in recent times in a number of scientific meetings, workshops, symposia, and technical sessions on TB (WHO 2015b, c; IUATLD 2015). The WHO in 2016 (WHO 2016a) informed that:

… accelerating the annual decline in TB incidence, reaching the 2020 milestone of a 35% reduction in TB deaths, requires reducing the global number of people with TB who will die from the disease (the case fatality ratio, or CFR) from 17% in 2015 to 10% by 2020.

The WHO’s End TB Strategy (where every case of TB counts, no matter what its source) accepted by the World Health Assembly in 2014 (WHO 2015b) and the Global Plan to End TB in 2016–2020 (Stop TB Partnership 2015) further emphasize the need to address these deficiencies and to include the issue of zoonotic tuberculosis in planning the eventual eradication of TB. More importantly, the End TB objective was adopted as part of the global Sustainable Development Goals (UN 2015). Therefore, within this context, there were calls for better diagnosis and treatment of every human TB case, including those with zTB.

Apart from the aforementioned, the lack of global concern about zTB remains a problem, given that human TB is generally, and specifically in some African countries, considered to be caused only by M. tuberculosis, without taking into account the role played by other members of the MTC, particularly M. bovis. Consequently, the general consensus was that current global initiatives to control and eradicate TB must involve a more holistic approach. This is based on the knowledge that a critical mass of the world population lives in neglected communities where cohabitation with animals (particularly cattle) is common. Thus, as a way forward, a pragmatic approach to end TB must incorporate an all-inclusive strategy that will simultaneously focus on the disease in both humans and animals. Toward this end, a meeting of a committee of experts from academia, WHO, the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), the FAO, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (IUATLD), and relevant research institutions was held at the WHO headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland, in April 2016 to deliberate on key priorities needed to reduce the burden of zTB. This culminated in the acceptance of zTB as a priority of the WHO at its Strategic Technical Advisory Group for TB (STAG-TB) meeting in June 2016 (Green 2006; WHO 2016b).

Because of the uncertainty about the actual number of zoonotic TB cases, the future prevention and control of M. bovis infections require the improvement of, and the use of rapid and accurate diagnostic tools, more comprehensive surveillance programs and greater collaboration between veterinary and medical health officials (Perez-Lago et al. 2014; WHO 2016b). These challenges provide an opportunity to reflect on the need for applying the principles of One Health to the control and eventual eradication of BTB and zTB.

4 The Burden of TB in Africa

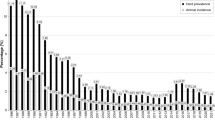

As of 2016, Africa’s 54 countries are home to approximately 1 billion people, constituting about 16% of the 7.4 billion people in the world. Although it has abundant natural resources and is showing signs of economic growth, Africa remains the world’s poorest and most underdeveloped continent. Multiple factors have been advanced for its underdevelopment, which include corruption in government settings occasioned by serious human rights violations, civil wars, failing central planning, high levels of illiteracy, and poor healthcare services resulting in the spread of deadly diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and TB (UNDP/HDRO 2013). Worse still, Africa currently carries the highest burden of TB (28% of the world’s cases in 2014) relative to its population (281 per 100,000 population), which is more than double the global average of 133 per 100,000 population (WHO 2015c). This situation is further worsened by the lack of surveillance and control measures to control BTB in the majority of the African countries (Cosivi et al. 1998; Thoen et al. 2009, 2010).

Overall, pertinent questions and key issues have yet to be addressed when BTB and zTB are considered in Africa (Thoen et al. 2010; El Idrissi and Parker 2012; Olea-Popelka et al. 2016). These include a lack of:

-

1.

An estimate of the prevalence of BTB in most African countries

-

2.

The burden of the disease in human populations at risk of infection

-

3.

Optimal methods to document human-to-human transmission of the disease after possible zoonotic infection in both rural and urban settings

-

4.

An understanding of the molecular epidemiology of BTB (cattle) and zTB (cattle and humans) for the purpose of developing adequate prevention and control strategies.

5 Concrete Steps Toward Setting an Agenda for the Control of Bovine and Zoonotic TB in Africa

A paradigm shift is required to address the challenge of BTB and its zoonotic burden on vulnerable human populations in Africa. To help achieve this, a concrete roadmap of implementable actions will be needed using multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches that include governments, politics, education, health, and various interest groups within a practical national and international framework (Fig. 4.1). Borrowing from the expert submission made in June 2016 to the STAG-TB in Geneva by experts from WHO, FAO, OIE, and IUATLD, ten key areas for the roadmap were suggested (WHO 2016b):

-

1.

Improved surveillance

-

2.

Development of novel diagnostic tools

-

3.

Coordinated research

-

4.

Disease control in animals

-

5.

Targeting key populations

-

6.

Food safety

-

7.

Raising awareness and engaging stakeholders

-

8.

Developing policies and guidelines

-

9.

Joint human/animal interventions

-

10.

Commitment and funding by government and international organizations.

Veterinarians, physicians, sociologists, epidemiologists, geographers, public health experts, policy makers, and particularly livestock workers should be included. On the whole, the benefit accrued must be for all with the goal of controlling and reducing BTB and zTB to the barest minimum in Africa. In order to make progress, the One Health framework and principles must therefore be taken into consideration.

6 The Genesis and Principles of One Health

One Health evolved from the concept of One Medicine and focuses on health and ecosystems to achieve global public health for humans, healthy animals, and a stable and sustainable environment (Thoen et al. 2016). Health experts from around the world met in September 2004 for a symposium organized by the Wildlife Conservation Society of New York, hosted by The Rockefeller University, USA, that focused on the potential spread of diseases between humans, domestic animals, and wildlife populations, to address these issues. Using case studies on Ebola, avian influenza, and chronic wasting disease as examples, the assembled experts and panelists delineated priorities for an international, interdisciplinary approach for combating threats to global health. Thereafter, veterinarians, physicians, public health experts, sociologists, and epidemiologists globally supported the concept of One Health, which they believed would promote surveillance and enhance the prevention, control, and eradication of zoonotic diseases. The vision of One Health therefore is “dedicated to improving the lives of all species—human and animal—through the integration of human and veterinary medicine.” Furthermore, “Recognizing that human and animal health are inextricably linked, One Health seeks to promote, improve, and defend the health and well-being of all species by enhancing cooperation and collaboration between physicians and veterinarians by promoting strengths in leadership and management to achieve these goals.”

The importance of One Health is palpable from the benefits derived in public health through positive interventions on animal diseases (Roth et al. 2003; Zinsstag et al. 2009) by joint healthcare services (Thoen et al. 2016), as well as positive outcomes observed by joint disease surveillance (Mazet et al. 2009). Since most countries in Africa are burdened with a high prevalence of BTB (Gibson et al. 2004), a practical way forward, and to reduce the human burden of the disease, is to embrace and incorporate the One Health approach to help prevent and control human infections with M. bovis, for which cattle serve as its natural host.

7 Target Populations/Communities and Mitigations

An important strategy toward achieving community mobilization is the active engagement of the population/community of interest. These engagements will include periodical community outreaches involving sensitization and health awareness talks on zoonotic diseases.

In Africa, participation of three principal stakeholders/communities is important to stem the tide of BTB and its zoonotic implications, namely, the pastoralist community (the livestock producers), livestock marketers, and butchers (livestock processors) (Adesokan et al. 2012). These groups are the populations at risk and are most vulnerable to zoonotic infections due to M. bovis. Fundamentally, they are unlikely to have the education and awareness of important health and hygiene precautions, and they engage in habits and practices that expose them to infection with M. bovis. These risky practices and activities include:

-

1.

Living closely with infected animals

-

2.

Consumption of unpasteurized dairy products and of improperly cooked, contaminated meat products

-

3.

Lack of the use of protective clothing/equipment during slaughtering

-

4.

Other unhygienic habits during milk and meat processing

Consequently, to reduce the spread of zTB in Africa, the activities and actions to be implemented based on the One Health approach should be directed at these neglected and at-risk populations.

The implementable actions that will promote activities to reduce the problem currently being experienced by Africans as a result of BTB using the One Health approach are discussed below.

7.1 Intergovernmental Collaboration

To make meaningful progress in the fight against BTB in Africa from both the animal and human perspective, the heads of government of the entire region must first be made to appreciate the enormity of the problem (through local and international policy briefings as well as joint summits) and accept that BTB is a major challenge to animal productivity and human health. After this has been achieved, a central committee at the African Union (AU) secretariat, given its leadership and political clout to promote regional health initiatives, as has been done for HIV/AIDS, malaria, and TB, should be set up. This committee should, with the technical support of the OIE, focus on promoting and coordinating inter-sectorial collaboration between the Ministries of Health and Agriculture/Livestock Resources in the various African countries. Using this platform, the embracement of a holistic application of the One Health approach to prevent and control BTB in animal production and zoonotic transmission will be greatly enhanced. An initiative to deal with BTB similar to the current collaboration initiated between the medical, veterinary, and agriculture departments across Africa by the AU in tackling the epidemics of avian influenza and Ebola should also be established.

7.2 Global Inter-sectoral Support and Collaboration for Africa by the WHO–FAO–OIE Tripartite

Similar global efforts, coordination, and funding to stem the tide of M. tuberculosis in humans in Africa should be established to deal with zTB. In this regard, for effective prevention and control of BTB in the animal and human populations, the tripartite initiative involving the WHO, FAO, and the OIE must be strengthened to chart and coordinate a “practical and cost-effective” roadmap that can be implemented in all African countries. This tripartite collaboration must be seen to be working with individual African countries, taking into consideration key issues like prevalence and burden of the disease in both the animal and the human populations. This was reflected in the submission made by teams of experts at the June 2016 WHO-STAG-TB meeting (WHO 2016b). Other fundamental considerations that must be implemented should include the establishment of prevention and control policies and guidelines dealing with the movement of cattle and humans within countries and across their borders, the cattle trade, and clarifying the epidemiology of BTB. Consideration of, and understanding, these factors will be important when developing the roadmap since they will provide insights into the sociocultural and population dynamics characteristic of each local setting.

7.3 Joint Veterinary–Medical Education/Training

To promote One Health in relation to BTB and zTB prevention and control in Africa, there is a need for the development of joint One Health curricula in medical and veterinary faculties on the continent (Zinsstag et al. 2005; Monath et al. 2010). This should involve programs that can be conducted jointly focusing on pastoralist communities, livestock markets, and abattoirs for the purpose of training and community interventions. A practical example is the initiative of the MacArthur Foundation for Higher Education in Africa in establishing Centers of Excellence. Through this initiative, a Center of Excellence for the Control and Prevention of Zoonoses (CCPZ) was established at the University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria, with the aim of prevention and control of endemic, emerging, and reemerging zoonoses (including BTB and brucellosis) in Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Through this platform, among other things, active surveillance and screening for BTB in cattle and livestock workers at the abattoirs and livestock markets were conducted by a team of veterinarians, community health physicians, and related disciplines. It is expected that similar initiatives will help to establish teams that can be mobilized to conduct tuberculin tests screening cattle for BTB. Following confirmation of BTB in a specific group of cattle, the medical team can then be invited to investigate possible zoonotic infections and to determine the burden of the disease in the affected human population. Such initiatives will further help to promote public awareness of the risk of consuming unpasteurized or non-heat-treated dairy products and contaminated meat and food products.

7.4 Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs)

In most African countries, the private sector plays a key role in TB control. The level of support given by the private sector, however, varies across the continent in terms of size, funding ability, level of organization, services rendered, and the communities supported. Using the One Health approach, African governments can partner with established nongovernmental organization (NGOs) that address TB, for example, the KNCV TB Foundation in the Netherlands, the German TB and Leprosy Foundation, the Belgian Damien TB and Leprosy Foundation, the IUATLD, and a host of well-established local groups to work actively with populations at risk. A successful model is the African Program for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC), which involved 28 African countries, a pharmaceutical company (Merck), and more than 30 development partners for the successful control of river blindness. Furthermore, Private Public Partnership (PPP) initiatives involving veterinary and medical teams working in different African countries can be established and mobilized, as was recently done during the Ebola outbreaks in some Western African countries (EU 2016). This becomes imperative in rural settings where information about the status of BTB has to be investigated to educate the inhabitants on practices related to pasteurization or heat treatment of dairy products before consumption. This is even more important given the need to mobilize the right personnel and experts to facilitate the necessary actions to control BTB in cattle and zTB in humans. Here, the international agencies listed above, including NGOs, and local groups will need to be mobilized both in rural and urban areas to increase public awareness about the risks of keeping and rearing cattle with BTB and, more importantly, the risk of consuming unpasteurized or non-heat-treated dairy products.

7.5 Clinical Research and Scientific Investigation

To achieve optimal care for patients with suspected zTB, clinical care is better achieved when there is cooperation and collaboration between the veterinary and medical investigators. A valid, rapid, point-of-care test that can differentiate between M. bovis and M. tuberculosis should be developed and deployed to screen patients (at hospitals and clinics) and “at-risk populations” selected from different livestock settings (Kaneene et al. 2014a, b). Based on the findings, appropriate and optimal care can then be given to the patient. Alternatively, routine samples at the hospitals and clinics should be inoculated on Lowenstein-Jensen media, one with glycerol and the other without glycerol but containing pyruvate to ensure growth for cases where M. bovis are suspected. In addition, active detection of zoonotic TB (i.e., through periodic visits by mobile clinics in at-risk populations in different livestock settings) should be encouraged and promoted to allow proper documentation of cases involving M. bovis as was the practice with the Health for Animal and Improved Livelihood (HALI) project in Tanzania. With these measures in place, it would become easier for a joint team of veterinarians and physicians to conduct coordinated outreach clinical sessions and investigations among livestock workers in pastoralist communities, livestock markets, and abattoirs. Through such initiatives, there will be a better likelihood of detecting unreported cases of human infections with M. bovis and M. tuberculosis, which can subsequently be treated earlier, thus preventing further spread of the disease.

8 Advantages and Future Areas of Importance of the One Health Approach in the Control of Bovine and Zoonotic TB

The overall advantage of an integrated One Health approach to solving the problems of BTB and zTB will be the optimization of monitoring and surveillance systems to assess the overall burden of TB in animals and humans in Africa (Kaneene et al. 2014a, b). The impact of this will be demonstrated over time through the decline (measured through coordinated programs and targets) in the burden of the disease in both human and animal populations in local communities, individual countries, and Africa as a whole. Because of this, and equally important, the valuable money and time saved can be applied to developing the livestock sector on the continent, thereby creating wealth instead of enhancing poverty and death.

As we move along this new roadmap toward tackling BTB and zTB, further research areas that involve methods to control M. bovis must be proposed and pursued. This should include the disciplines of sociology (risk perception and hygiene), economics (the cost for the community and disability-adjusted life years—DALYs), and ecology (movement of animals and contact networks between species) (Roger 2012). As a follow-up to this, there is a need to form a coalition of experts within each country, and throughout the continent as a whole, in cooperation with other key stakeholders, to promote constant monitoring and surveillance, to gather comprehensive data at all epidemiological sites (pastoralist settings, livestock markets, abattoirs, hospitals/laboratories), and to work toward the reduction and control of the disease in animal and human populations. More importantly, this range of activities will ultimately inform the level of funding that will be required to support long-term goals at the community, state, and national levels in affected African countries.

9 Conclusion

After many years of inaction and poor coordination by the global community, it has now become imperative that the problems and challenges posed by BTB and zTB in Africa must be addressed. A similar need was vividly captured by the editorial published in the American Journal of Public Health almost a century ago (Anon 1932) where it was stated:

Who can calculate the number of lives saved and the amount of crippling (tuberculosis ranks second as a crippling disease) avoided if we had followed the advice of Abraham Jacobi, great man and great physician, and had been as active in our efforts against bovine infection of children as we have been against the human? The facts have been before us for 30 years. They have been proved and re-proved. Is there any excuse for longer complaisance or inaction?

As we reflect on these words, and given the lack of progress to achieve the stated objectives, African governments, scientists, and key stakeholders must join hands with global agencies such as the WHO, the FAO, the OIE (to mention a few), and the IUATLD (that for many years housed a small but influential group of veterinarians and physicians dedicated to the issue of zoonotic TB) and map out strategies to reduce the prevalence and threat of BTB and the burden of zTB in Africa’s human population (Olea-Popelka et al. 2016). More importantly, inter-sectorial collaboration particularly between veterinarians and the medical personnel across Africa must be strengthened to combat this disease. This collaboration should be directed at encouraging training programs at universities and related tertiary institutions and major stakeholders to engender advocacy (public health awareness), sustainability (continuous screening and monitoring), and progress (positive implementation of guidelines and policies by government agencies) in the fight against BTB and zTB particularly in neglected communities in the rural areas.

The way forward therefore is to develop a “Marshall Plan” of action (as highlighted earlier) that will help by employing a One Health approach to reduce the burden of BTB in livestock, wildlife, and zTB in humans. This roadmap is now contained in a recent document, Roadmap for Zoonotic Tuberculosis, which outlines the strategy to deal with the issue (WHO 2017). The overarching approach should focus on coordinated public education campaigns and interventions utilizing existing knowledge applied at a local level in a simple and practical way. Finally, cattle and certain wildlife species are maintenance hosts of M. bovis in the region, and unless BTB is controlled in Africa in all the infected species, the WHO’s goal of ending all forms of TB will be impossible to accomplish.

References

Adesokan HK, Jenkins AO, van Soolingen D et al (2012) Mycobacterium bovis infection in livestock workers in Ibadan, Nigeria: evidence of occupational exposure. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 16(10):1388–1392

Anon (1932) Bovine tuberculosis and human health. Am J Public Health 22(8):840–843

AU-IBAR (2013) Tuberculosis. http://www.au-ibar.org/tuberculosis. Accessed 28 July 2016

Ayele WY, Neill SD, Zinsstag J et al (2004) Bovine tuberculosis: an old disease but a new threat to Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 8:924–937

Brosh R, Gordon SV, Marmiesse VM et al (2002) A new evolutionary scenario for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:3684–3689

Cadmus S, Palmer S, Okker M et al (2006) Molecular analysis of human and bovine tubercle bacilli from a local setting in Nigeria. J Clin Microbiol 44:29–34

Cosivi O, Grange JM, Daborn CJ et al (1998) Zoonotic tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis in developing countries. Emerg Infect Dis 4:59–70

Daniel R, Evans H, Rolfe S et al (2009) Outbreak of tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis in golden Guernsey goats in Great Britain. Vet Rec 165:335–342

de Garine-Wichatitsky M, Caron A, Kock R et al (2013) A review of bovine tuberculosis at the wildlife-livestock-human interface in sub-Saharan Africa. Epidemiol Infect 141(7):1342–1356

de Lisle GW, Bengis RG, Schmitt SM et al (2002) Tuberculosis in free-ranging wildlife: detection, diagnosis and management. Rev Sci Tech 21(2):317–334

Egbe NF, Muwonge A, Ndip L et al (2016) Abattoir-based estimates of mycobacterial infections in Cameroon. Sci Rep 6:24320

El Idrissi A, Parker E (2012) Bovine tuberculosis at the animal-human-ecosystem interface. EMPRES Transb Anim Dis Bull 40:2–11

Etchechoury I, Valencia GE, Morcillo N et al (2010) Molecular typing of Mycobacterium bovis isolates in Argentina: first description of a person-to-person transmission case. Zoonoses Public Health 57:375–381

EU (2016) EU response to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. European Commission-Fact Sheet. https://europa.eu/newsroom/highlights/special-coverage/ebola_en. Accessed 9 June 2016

Evans JT, Smith EG, Banerjee A et al (2007) Cluster of human tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis: evidence for person-to-person transmission in the UK. Lancet 369:1270–1276

Gibson AL, Hewinson G, Goodchild T et al (2004) Molecular epidemiology of disease due to Mycobacterium bovis in humans in the United Kingdom. J Clin Microbiol 42:431–434

Godreuil S, Jeziorski E, Banuls AL et al (2010) Intrafamilial cluster of pulmonary tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis of the African 1 clonal complex. J Clin Microbiol 48:4680–4683

Gortázar C, Delahay RJ, McDonald RA et al (2012) The status of tuberculosis in European wild mammals. Mammal Rev 42:193–206

Green A (2006) Experts recognise zoonotic TB. Lancet Respir Med 4:433

Hiko A, Agga GE (2011) First-time detection of Mycobacterium species from goats in Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod 43:133–139

Hlavsa MC, Moonan PK, Cowan LS et al (2008) Human tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis in the United States, 1995–2005. Clin Infect Dis 47:168–175

Houlihan MG, Williams SJ, Poff JD (2008) Mycobacterium bovis isolated from a sheep during routine surveillance. Vet Rec 163:94–95

IUATLD (2015) International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease: world conference on lung health in Cape Town, South Africa, 2–6 December, 2015. http://edition.cnn.com/2015/12/23/health/tuberculosis-from-animals/index.html

Jenkins AO, Cadmus SI, Venter EH et al (2011) Molecular epidemiology of human and animal tuberculosis in Ibadan, Southwestern Nigeria. Vet Microbiol 151:139–147

Kaneene JB, Kaplan B, Steele JH et al (2014a) One Health approach for preventing and controlling tuberculosis in animals and humans. In: Thoen CO, Steele JH, Kaneene JB (eds) Zoonotic tuberculosis – Mycobacterium bovis and other pathogenic mycobacteria. Wiley-Blackwell, Ames, IA, pp 9–20

Kaneene JB, Miller RA, Kaplan B et al (2014b) Preventing and controlling zoonotic tuberculosis: a One Health approach. Vet Ital 50(1):7–22

Kriek N (2014) Tuberculosis in animals in South Africa. In: Thoen O, Steele JH, Kaneene JB (eds) Zoonotic tuberculosis: Mycobacterium bovis and other pathogenic mycobacteria, 3rd edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Ames, IA, pp 99–108

Kudi AC, Bello A, Ndukum JA (2012) Prevalence of bovine tuberculosis in camels in Northern Nigeria. J Camel Pract Res 19:81–86

LoBue PA, Betancourt W, Cowan L et al (2004) Identification of a familial cluster of pulmonary Mycobacterium bovis disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 8:1142–1146

Majoor CJ, Magis-Escurra C, van Ingen J et al (2011) Epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis disease in humans, The Netherlands, 1993–2007. Emerg Infect Dis 17:457–463

Mazet JAK, Clifford DL, Coppolillo PB et al (2009) A “One Health” approach to address emerging zoonoses: the HALI project in Tanzania. PLoS Med 6(12):e1000190

Mendoza MM, de Juan L, Menéndez S et al (2012) Tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium caprae in sheep. Vet J 191:267–269

Michel AL, Bengis RG, Keet DF et al (2006) Wildlife tuberculosis in South African conservation areas: implications and challenges. Vet Microbiol 112(2–4):91–100

Mignard S, Pichat C, Carret G (2006) Mycobacterium bovis infection, Lyon, France. Emerg Infect Dis 12:1431–1433

Miller R, Kaneene JB, Schmitt SM et al (2007) Spatial analysis of Mycobacterium bovis infection in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in Michigan, USA. Prev Vet Med 82:111–122

Moiane I, Machado A, Santos N et al (2014) Prevalence of bovine tuberculosis and risk factor assessment in cattle in rural livestock areas of Govuro district in the Southeast of Mozambique. PLoS One 9(3):e91527

Monath TP, Kahn LH, Kaplan B (2010) Introduction: One Health perspective. ILAR J 51:193–198

Müller B, Dürr S, Alonso S et al (2013) Zoonotic Mycobacterium bovis-induced tuberculosis in humans. Emerg Infect Dis 19:899–908

Munyeme M, Muma JB, Skjerve E et al (2008) Risk factors associated with bovine tuberculosis in traditional cattle of the livestock/wildlife interface areas in the Kafue basin of Zambia. Prev Vet Med 85:317–328

Naima S, Borna M, Bakir M et al (2011) Tuberculosis in cattle and goats in the north of Algeria. Vet Res 4(4):100–103

Olea-Popelka F, Muwonge A, Perera A et al (2016) Zoonotic tuberculosis in human beings caused by Mycobacterium bovis – a call for action. Lancet Infect Dis 17(1):e21–e25

Oloya J, Opuda-Asibo J, Kazwala R et al (2008) Mycobacteria causing human cervical lymphadenitis in pastoral communities in the Karamoja region of Uganda. Epidemiol Infect 11(136):636–643

Palmer MV, Thacker TC, Waters WR et al (2012) Mycobacterium bovis: a model pathogen at the interface of livestock, wildlife, and humans. Vet Med Int 2012:236205, 17. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/236205

Perez-Guerrero L, Milian-Suazo F, Arriaga-Diaz C et al (2008) Molecular epidemiology of cattle and human tuberculosis in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 50:286–291

Perez-Lago L, Navarro Y, Garciav de Viedma D (2014) Current knowledge and pending challenges in zoonosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis: a review. Res Vet Sci 97:S94–S100

Porphyre T, Stevenson MA, McKenzie J (2008) Risk factors for bovine tuberculosis in New Zealand cattle farms and their relationship with possum control strategies. Prev Vet Med 86(1–2):93–106

Radunz B (2006) Surveillance and risk management during the latter stages of eradication: experiences from Australia. Vet Microbiol 112:283–290

Renwick AR, White PC, Bengis RG (2007) Bovine tuberculosis in southern African wildlife: a multi-species host–pathogen system. Epidemiol Infect 135:529–540

Rodwell TC, Moore M, Moser KS et al (2008) Tuberculosis from Mycobacterium bovis in binational communities, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 14:909–916

Roger F (2012) Control of zoonotic diseases in Africa and Asia. The contribution of research to One Health. Perspect Policy Brief 18:4

Roth F, Zinsstag J, Orkhon D et al (2003) Human health benefits from livestock vaccination for brucellosis: case study. Bull World Health Organ 81:867–876

Siembieda JL, Kock RA, McCracken TA et al (2011) The role of wildlife in transboundary animal diseases. Anim Health Res Rev 12:95–111

Smith NH, Kremer K, Inwald J et al (2006) Ecotypes of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Theor Biol 239(2):220–225

Stone MJ, Brown TJ, Drobniewski FA (2012) Human Mycobacterium bovis infections in London and Southeast England. J Clin Microbiol 50:164–168

Stop TB Partnership (2015) Global plan to end TB 2016–2020 – the paradigm shift. http://www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/global/plan/GlobalPlanToEndTB_TheParadigmShift_2016-2020_StopTBPartnership.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2016

Sunder S, Lanotte P, Godreuil S et al (2009) Human-to-human transmission of tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis in 11 immunocompetent patients. J Clin Microbiol 47:1249–1251

Thoen CO, LoBue PA (2007) Mycobacterium bovis tuberculosis: forgotten, but not gone. Lancet 369:1236–1238

Thoen CO, LoBue PA, Enarson DA et al (2009) Tuberculosis: a re-emerging disease in animals and humans. Vet Ital 45(1):135–181

Thoen CO, LoBue P, de Kantor I (2010) Why has zoonotic tuberculosis not received much attention? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 14(9):1073–1074

Thoen CO, Kaplan B, Thoen TC et al (2016) Zoonotic tuberculosis: a comprehensive One Health approach. Medicina (B Aires) 76:159–165

Torres-Gonzalez P, Soberanis-Ramos O, Martinez-Gamboa A et al (2013) Prevalence of latent and active tuberculosis among dairy farm workers exposed to cattle infected by Mycobacterium bovis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7(4):e2177

UN (2015) Sustainable development goals. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/. Accessed 30 May 2016

UNDP/HDRO (2013) United Nations Development Programme, pp 144–147

WHO (2015a) WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases. Geneva: WHO, Foodborne diseases burden epidemiology reference group 2007–2015. http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/foodborne_disease/fergreport/en/. Accessed 24 Aug 2016

WHO (2015b) WHO end TB strategy. http://who.int/tb/post2015_TBstrategy.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 6 Nov 2015

WHO (2015c) End TB strategy (WHO/HTM/TB/2015.19). http://who.int/tb/post2015_TBstrategy.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 6 Nov 2015

WHO (2016a) World Health Organization global tuberculosis report. http://www.who.int/tb/; http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed 17 Oct 2016

WHO (2016b) Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Tuberculosis (STAG-TB) Report of the 16th Meeting of the Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Tuberculosis (STAG-TB), 13–15 June, 2016. WHO Headquarters, Geneva, pp 21–22. http://www.who.int/tb/advisory_bodies/stag_tb_report_2016.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 26 Jan 2017

WHO (2017) Roadmap for zoonotic tuberculosis. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/259229/1/9789241513043-eng.pdf. Accessed 20 Mar 2018

WHO-FAO (1994) Zoonotic tuberculosis (Mycobacterium bovis): memorandum from a WHO meeting (with the participation of FAO). Bull World Health Organ 72:851–857

Zinsstag J, Schelling E, Wyss K et al (2005) Potential of cooperation between human and animal health to strengthen health systems. Lancet 366:2142–2145

Zinsstag J, Dürr S, Penny MA et al (2009) Transmission dynamics and economics of rabies control in dogs and humans in an African city. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(35):14996–15001

Acknowledgment

Partial funding support received by Simeon Cadmus from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, USA, under the Higher Education Initiative in Africa (Grant No. 97944-0-800/406/99) for the establishment of the Center of Control and Prevention of Zoonoses (CCPZ) at the University of Ibadan is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cadmus, S.I.B., Fujiwara, P.I., Shere, J.A., Kaplan, B., Thoen, C.O. (2019). The Control of Mycobacterium bovis Infections in Africa: A One Health Approach. In: Dibaba, A., Kriek, N., Thoen, C. (eds) Tuberculosis in Animals: An African Perspective. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18690-6_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18690-6_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-18688-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-18690-6

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)