Abstract

Richard Easterlin’s lifetime happiness theory holds that people get less happy over the life-cycle as exaggerated expectations hit; this has been found to be true for the 20–50 age range in many Western countries. This paper looks at the implications for child happiness and asks: when does the ‘disappointment with reality’ start to bite in early life, i.e. when does happiness drop? We develop child-specific scales to measure the effect of personality and childhood life satisfaction domains. With an internet-based survey, we collect unique data from 389 Australian children aged 9–14. Adding to previous findings that satisfaction levels Australian life decline between age 15 and 23 by almost 0.7 on a ten-point scale, we find an even steeper decline before age 14. Using a decomposition method, we show that the natural environment domain has no significant effect on childhood life satisfaction, whilst the children’s school environment and interaction with friends domains explain over 40% of the decline in childhood life satisfaction. This decline is steepest when the children transition to high school. As expected, extraverted children are happier, but unexpectedly, so are conscientious children.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In 1974, Richard Easterlin alerted economists and social scientists generally to the failure of higher GDP to buy more happiness. Basing himself on 8 countries, and information for the US going back since the 1940s, he found no long-run relation between the growth of the overall economic pie and the average level of happiness in a country. He explicitly explained this with a simple theory of social comparisons wherein the amount of happiness that individuals get out of their incomes depends on what others earn: if the waters rise, all boats rise equally and none has grown relative to the others.Footnote 1

In 2001, Richard then published a more detailed theory of how this might work over the life-cycle. He postulated that individuals are prone to a particular irrationality: they expect their incomes to grow over their life, but they expect their own ideas as to what they would need to be happy to remain the same. So they expect to end up with a lot of income relative to their benchmark level as determined in childhood, feeling happy about that prospect. As reality sets in, which includes people adapting their benchmark to what they earned in the recent past and what their neighbours earn, they get less happy as life goes on, particularly when their incomes grow less than originally anticipated.

Richard’s elegant 2001 theory was of course highly stylised and by necessity did not capture all the nuances of real lives. It should thus not be taken too literally, but nevertheless has a couple of components worth confronting with data. One main one is of course whether or not people indeed adapt their material benchmarks. Richard Easterlin’s 2005 paper used the small Roper Foundation surveys from 1978 and 1994, concluding “The evidence I have presented suggests that pecuniary or living level aspirations tend to change, on average, to about the same extent as actual circumstances. In contrast, aspirations with regard to marriage and number and quality of children appear to be more stable and vary less as actual circumstances change”.

In this paper we want to look at the implications for child happiness that Richard’s story implies. For one, his 2001 theory implies that people get less happy over the life-cycle. This has been found to be true for the 20–50 age range in many Western countries, though the consensus is now that this is followed by a late-life happiness wave: a retirement surge in happiness that only fades close to death. This perchance reflects a phenomenon that Richard probably was aware of but couldn’t get to work in his 2001 model, which is a ‘letting go’ after retirement of the importance of previous aspirations, followed by a greater capacity to enjoy the lack of responsibilities of retired life.

But when does the ‘disappointment with reality’ start to bite earlier in life? Can we already see before the age of 20 whether children lose their innocent belief in a fantastic new future where they will be richer than their benchmark? More simply: when does the happiness downturn begin?

A related question is the issue of relative comparisons generally. Are children already affected by relative income comparisons and thus already on the ‘hedonic treadmill’ of socially determined wants? And if not, when does relative wealth become more important?

And finally, is it true that children have inflated expectations of the future and their ability to achieve good outcomes in that future?

We will try to answer these questions, and some others, in a unique dataset that we gather in 2008 in Queensland, the North-Eastern state of Australia. We were lucky enough to then be invited to design a web-based survey for school children who attended exhibitions in a ‘Smart Train’ that went via several regional stations in Queensland. We ran a lottery to give a prize amongst those willing to participate in our survey and got some 400 responses from children aged 9–14.

This is not a huge survey. Neither is it very representative. And, in hindsight, we did not ask all the questions we would have liked to answer the questions above. Yet, happiness information on children is very rare and we know of no studies that look at relative income effects amongst children. Also, nothing on our dataset has been previously published, so using the dataset to look for information on the childhood implications of Richard’s 2001 theory is our small contribution to celebrate the immense impact that Richard Easterlin has made on social science.

We first discuss the literature on childhood happiness, moving on to our survey, the results, and a discussion of those results.

1.1 The Literature on the Happiness of Children Versus Adults

The study of life satisfaction in adults has become a major area of research in the social sciences (Diener 1984; Stutzer and Frey 2012). Yet, as Heubner and Diener (2012, p. 383) conclude in their survey of the literature, “Research in children’s school and life satisfaction is in its infancy”. We add to the small literature on life satisfaction amongst children by looking at the changes in 9–14-year olds in a sample of 389 Australian school children.

From the few studies available, Heubner and Diener (2012, p. 379) state that “Global life satisfaction reports of children, above the age of 8, do not appear to differ significantly as a function of age”. At the outset, we did not quite believe this: there are quite a few studies that report that children who are in early junior high school or in early adolescence experience an increase in mental health problems and a decrease in their satisfaction with school itself (Hirsch and Rapkin 1987; Huebner et al. 2000). This raises the possibility that sample sizes or other methodological issues have so far prevented a clear age-happiness profile to be found amongst children. We revisit this issue. Relevant to economists is also the question whether the very strong relation between life satisfaction and perceived relative wealth amongst adults (Headey and Wooden 2004; Clark et al. 2008) also shows up for children: does relative wealth buy childhood happiness?

Currently, the main information on life satisfaction in Australia comes from the Household and Income Dynamics Australia (HILDA 2013). In Fig. 18.1 we show the age-profile amongst the respondents, showing a drop in happiness of around 0.7 between the age of 15 and 23 on a ten-point scale, leading to the question of what happens before then.

Childhood studies on global life satisfaction are infrequent in the economics literature but more prevalent in the psychological and other literatures, although still far fewer than the number of studies on the concept of subjective well-being (Diener and Suh 1998; Easterlin 2001; Seligman 2011).

In economics, children have usually been considered in the context of the negative (Stutzer and Frey 2006; White 2006) or positive (Tsang 2003) effect they have on adult happiness, not their own happiness. A typical example is Bruhin and Winkelmann (2009) who looked at the relationship between parents and their adult children’s subjective well-being in a German panel, where the happiness of children was not measured. In a related vein, some economic studies have looked at the childhood predictors of adult life satisfaction (Flouri 2004; Frijters et al. 2011).

The few economic studies looking at the life satisfaction of children themselves have mainly looked at adolescents above 14 and their family. Bedin and Sarriera (2015) did a comparative analysis of the subjective well-being of parents and their 12 to 16 year-old adolescent children regarding gender, age and social class. Carlsson et al. (2014) looked at the intergenerational transmission of happiness in China between preadolescents and their parents. Ebner’s (2008) longitudinal study used the European Community Household Panel data (ECHP 2015) to reveal that adolescents are happier when they make the decision to leave the family home. A study by Dockery (2005) used data from the (1997–2004) Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth (LSAY 2012) and wave 1 of the HILDA and found evidence of declining levels of happiness in adolescents during periods of unemployment. He also documents the importance of the quality and type of work to the happiness of adolescents. Ulker (2008), using the Australian HILDA data, found that adolescents become less happy when their parents’ divorce. Other studies looked at school performance or aggregate changes amongst children over the age of 14 (Cheng and Furnham 2004).

A few studies in economics look at life satisfaction in the 9–14 age range. Powdthavee and Vernoit (2013) examined the longitudinal relationship between parental unemployment and 11–15 year-old British children’s self-reported happiness with life scores over time. Fogle et al. (2002) cross-sectional study revealed a positive relationship between extraversion, social competence and life satisfaction among children aged 10–15 years from public schools in mid-sized cities in the South-East of the United States. A positive attitude, confidence in own abilities and the skills to interact with your peer group were found to be important to childhood happiness. Also focussing on school children, Huebner et al.’s (2005) cross-sectional study of public middle school students from South Carolina (U.S.A) proposed that family, friends, school and the environment in which children live and learn are important to childhood happiness. Lee and Oguzoglu (2007) longitudinal study of Australian youths ventured outside the school environment and found that income support payments contributed to childhood happiness. The main conclusion we draw from these is that personality, friends, and the school environment are prime candidates to explain change in the happiness of children over time and thus need to be included in the survey.

The literature in psychology and other social sciences on life satisfaction amongst adolescents older than 14 is much larger than in economics and has looked at a huge range of issues. The many topics looked at include the importance of academic success (Suldo et al. 2006), bullying (Moore et al. 2012), family structure (Levin et al. 2012), ethnicity (Campbell and Eggerling-Boeck 2006), obesity (Forste and Moore 2012), mental health (Ulker 2008; Dear et al. 2011; Antaramian et al. 2010), and low income (Levin et al. 2011).

If we look at the literature on global life satisfaction of children aged 9–14, there are far fewer studies, where the main finding relevant to the objectives of this paper is the lack of any clear change in life satisfaction level over age (Gilman and Huebner 2003). An early study is Huebner et al. (2005), who looked at 2278 public middle school students in the US and found that the influence of demographic variables in the level of happiness was limited, although middle school children were particularly dissatisfied with their school experiences. A later study by Antaramian et al. (2008) focused on the importance of family structure, finding that children in single parent or step-parent families were less satisfied with their lives. Heubner and Diener (2012) review roughly 20 papers that look at child satisfaction, which mainly deal with the development of proper measurement instruments and particular groups at risk of experiencing problems. These studies will be important in the next section dealing with data gathering.

2 Data and Survey Method

2.1 The HILDA Data

We use two data sets.Footnote 2 The first data set is the 15–93 year-olds from waves 2–13 of the ‘Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia’ Survey (HILDA, 2013)Footnote 3 and underlies Fig. 18.1. The second is our own data from younger children.

2.2 Collecting Data from Children

Collecting data from children is fraught with ethical, logistical and truthful self-reporting roadblocks (Gilman and Huebner 1997, 2000; Haranin et al. 2007). To avoid the issue of untruthful reporting when confronted with outside survey collectors, our collecting procedures follow the literature by folding it into the children’s normal teaching program, wherein school teachers took their classes to local railway stations to visit a ‘Smart Train’Footnote 4 that went from urban Brisbane throughout regional Queensland, with carriages containing university research displays; one of which explained happiness. Upon returning to school, the children were requested to complete an internet-based ‘Happiness’ survey. To encourage response, teachers were provided with ‘Happy Posters’ to hang on classroom walls and ‘Happy Teaching Guides’ with instructions on how the children could use their school computers to respond to our Childhood Happiness Survey.Footnote 5

To answer these questions, we gathered data on school children throughout Queensland, the north-eastern state in Australia, with the help of teachers and the Queensland Government. We measure various domains of life for these children, including school circumstances, social circumstances, the personality of the children, and their perceived relative wealth. After looking at the raw profile of happiness we apply techniques previously used in the economics literature (Frijters et al. 2004) to decompose the found changes in happiness as a function of changes in other variables.

2.3 Survey Questions

The meta-analysis of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents by Gilman and Huebner (2003) provides a summary of childhood happiness-affecting variables. Their list includes many factors, of which we choose the factors easiest to gather from the children themselves, including socio-economic variables that economists usually incorporate into their models of individual happiness (age, gender), as well as personality factors, life satisfaction domains, environment factors, and school variables. This means we did not gather variables that would require information of others, such as parental circumstances, medically assessed health and self-reflecting behaviour, which one would want to ask of teachers (such as asking whether the child causes problems for others).

2.3.1 The Happiness Question

The dominant happiness surveys are generally targeted at individuals 15 years and older. Since we wish to compare the findings for young children with these age ranges, we also use the Global Life Satisfaction question (Cummins 1996; Fordyce 1988; Wessman and Ricks 1966) wherein we ask children on a 1 (very unhappy) to 5 (very happy) scale:

All things considered in your life, how happy would you say you are usually?

The high response rate (100%) as well as the fact that these children had just seen exhibits on happiness research gives some confidence that children had an intuitive understanding of what was being asked.

2.3.2 Demographic Questions

In order to be able to ascribe changes in happiness to changes in circumstances, we wanted to have an array of demographic questions, which raised the issue of whether children as young as 9 would have a reasonable concept of such high-level circumstances such as their family’s income. Researchers have long been concerned with inaccuracies in how adults report their income (Moore et al. 2000), which makes it likely that the problem of misreporting is even higher amongst children. As a result we more directly ask about relative wealth, since children do understand the concept of money as they swap it with others to get what they want (Leiser and Beth Halachmi 2006). We furthermore suspected that relative comparisons are easier to understand than absolute levels: a child might not know what things cost or how much the family makes, but; will notice whose house is bigger, and; who is jealous of others for things they cannot afford. We thus asked:

Would you say that your family is; wealthier; the same; poorer than others in the neighbourhood.

A drawback of asking children to complete the questionnaire at school was that we could not ask information about the parents, such as their employment, years of education, relationship status, and recent shocks.

2.3.3 Personality

Amongst adult happiness studies (Lischetzke and Eid 2006; Wilson 1967), the personality traits most related to happiness are extraversion and emotional stability. It is an open question whether that is also true of children and hence whether there is a role for agreeableness, conscientiousness, or openness to experience. However, the survey instruments measuring these Big-5 personality constructs (Goldberg 1990) are only suitable for adults and adolescents as young as 12 years (Muris et al. 2005); not the 9−11 year olds that formed part of our target population.

We thus adopt the Big Five Questionnaire for Children (BFQ-C) of Barbaranelli et al. (2003). Their analysis of the internal validity of this scale revealed a high positive correlation between the BFQ-C scale completed by the children and their parent’s assessment of their child’s personality using the adult Big-5 questionnaire. In support of its use, del Barrio et al. (2006) successfully used the BFQ-C scale to assess the personality of eight to 12 year old school children. More recently, the study of 13–14 year olds by Barbaranelli et al. (2008) used multi-trait methods and confirmatory factor analysis to assess the validity of the BFQ-C and found convergent validity was supported for all five personality factors.

We had to adapt the BFQ-C scale for our purposes because it had 65 questions; twelve or more questions per personality trait is lot of questions for an internet survey.Footnote 6 Using BFQ-C psychometric property/correlation results from Muris et al. (2005), we constructed a short-form Big Five Questionnaire for Children (SBFQ-C) by choosing six questions per personality trait.Footnote 7 After data collection, confirmatory factor and Cronbach’s alpha analysis confirmed our chosen six questions per personality trait exhibited acceptable levels of convergence and scale reliability (Table 18.1).

2.3.4 The Life Satisfaction Domain Measures

Huebner (1991, 1994, 1995), Natvig et al. (2003), Seligson et al. (2005) and Suldo et al. (2006) provide theoretical directions that identify domains considered to correlate with childhood happiness; school environment, interaction with friends, and, the natural environment life satisfaction domains. The wording of the survey questions we developed for each domain was based on this. For example, because sharing, friendly, communicative children who like to interact with their peers are happier we posed the questions; l make friends easily, I like to talk to others, I like to help my classmates, I like to share with others, and, I am forgiving. These were included for the interaction with friends life satisfaction domain. The rationale for including forgiveness is that it has been found to be positively associated with childhood life satisfaction (Gilman and Huebner 2003).

When it comes to the school environment life satisfaction domain, Huebner et al. (1999) found it important to know whether children understand what the teacher says, can concentrate, work hard, get bored, whether they participate in structured extracurricular activities, and aspects of their academic life (including achievement and learning with classmates).

In addition to the life satisfaction domain questions, the children were asked questions about their natural environment. We asked the children if they were engaged in discussions on their natural environment; if they were aware of environmental problems; what they were doing about them; whether it was an acceptable behaviour to pollute their river or a river in a neighbouring state; and the importance of animals and plants in their live. These questions were coded as dummy variables and summed to form the natural environment life satisfaction domain factor, where 1 is the lowest level of concern for the natural environment and 13 the highest level of concern for the natural environment.

Table 18.2 lists the questions posed on these three domains. Results from Cronbach’s alpha test, and confirmatory factor analysis, revealed that all three life satisfaction domain factors offered an acceptable to high level of internal consistency and reliability.

Finally, we included a number of fun questions (on magic & handedness) to encourage the children to respond to our internet-based childhood happiness survey; see the natural environment and fun questions in Table 18.7.

3 Analyses

3.1 Summary Statistics

Of the 389 children who responded to the internet-based ‘Happiness’ survey, 327 visited the ‘Smart Train’ at one of 25 regional railway stations and 62 at the urban railway station (the state capital of Brisbane). There were 217 female and 172 male children (44%) respondents with an average age of 11.76 years.

Table 18.3 shows the summary statistics. Average life satisfaction for our 9 to 14-year-old sample is a very high 9.0 if we translate the scale to 0–10; 14% higher than the 7.91 we see in 15 to 23 year-olds in the HILDA and 12% higher than the average of 8.07 for the complete HILDA sample. Average happiness for female children in our sample (9.31) was 8% higher than for male children (8.60), a very significant difference (t = 3.59, p = 0.0004) that is commensurate with what is found later in life but which has not been in previous child studies (Heubner and Diener 2012). What drives this average difference in our data is the relatively low happiness of regional males versus regional females, which suggests that one of the reasons for the divergence with previous studies is that our data includes both urban and regional children.

Twelve per cent of the children self-reported as left-handed, a few percent more than the expected 10% (Johnston et al. 2009) and 47% reported a ring finger longer than their index finger; an indicator of the higher testosterone levels typical of males.

Turning to Table 18.7, which shows a summary of the natural environmental questions: children have a high awareness of environmental issues such as climate change (68%), and; water restrictions (59%), but; a much lower awareness of native animals dying out (42%); declining fish stocks (21%), and; land salinity (16%). Climate change (47%) and water restrictions (15%) were seen as the worst problems, with urban children showing more concern about climate change than regional children (61% versus 44%). We expected that regional children would show a higher awareness and concern for climate change and water restrictions, because the Millennium 2001–2010 series of droughts in Australia had such a severe negative economic effect on Australia’s rural and agricultural communities (SoE 2011). This was not the case though with regional children showing less awareness and concern for the environment.Footnote 8 Perhaps the reason for this arises from the attitudes of their parents. In Australia, more than twice as many urban dwellers (58%) are of the opinion that humans are causing climate change; versus just 27% for primary producers in regional areas (Donnelly et al. 2009, p. 5).

Overall, the children are not just showing concern for the natural environment, they are acting on that concern. Fifty-nine per cent of the children are engaging in recycling and 65% have tried to reduce their water consumption, and, the numbers are even higher for urban children (Table 18.4); more urban children (81%) than regional children (62%) had tried to reduce their water consumption, and a similar urban-rural difference held for engaging in recycling (73% versus 57%). The children are also showing concern about the poor environmental behaviour of others; 98% of the children said it was wrong to pollute a river, even if that river was in another state (99%). Based on these results, Australia’s next generation shows more concern for climate change and the natural environment than their parents, who answer the same questions 68% versus 53% (ABS 2010).

3.2 Extending Our View of Happiness over a Lifetime

We can now append the average happiness of the 9 to 14 year-olds from our ‘Smart Train’ sample to the graph of average happiness for the 15 to 93 year-old Australians from the HILDA (Figs. 18.2 and 18.3).

One thing one can notice is how well the lines match up from the data on the Smart Train with the HILDA data, which at least suggests that the sample is representative of the happiness of Australian children. The second thing we notice is that the steep happiness fall we previously saw in 15 to 23-year-olds extends back to 9-year-old children. Whilst 15 to 23 year-old Australians in the HILDA witness a 7.2% (−0.73 unit) decline in happiness, this is preceded by a further 9.3% decline (9.44–8.56, −0.88 units) between 9 and 14 years (dotted line in Figs. 18.2 and 18.3). The total fall in happiness from age 9 to age 23 is then 16.5% (−1.61 units).

In terms of the main Easterlin-related questions of the introduction, our first ‘result’ is hence that the decline in happiness starts at age 9 and 10, but becomes particularly pronounced from age 12 to 13, which coincides with the children’s transition to high school and the onset of puberty.

This very strong decline raises the question as to the factors responsible; we look at that next.

3.3 The Determinants of Life Satisfaction

In Eq. (18.1) we model life satisfaction of child (i) in age-group (t) as a linear function of the available variables:

where

-

LSit Individual life satisfaction (happiness)

-

C Constant

-

Xitindividual demographics (wealth, religion)

-

SitSchool environment life satisfaction domain factor

-

FitInteraction with friends life satisfaction domain factor

-

NitNatural Environment life satisfaction domain factor

-

ZiPersonality and gender

-

εiterror term

Here, childhood happiness (LSit) is a function of a constant (C), time-variant socio-economic variables specific to the individual (Xit) and individual traits (Zi). A child’s happiness is further affected by the school environment (Sit), interaction with friends (Fit) and natural environment (Nit) life satisfaction domains, with unobservables manifest in an error term (εit).

Regression results for different specifications are shown in Tables 18.5 and 18.6, which progressively include more factors. Looking at Table 18.5, specification 1a, we see that girls are happier (+0.63) than boys and attending religious services more often is related to higher happiness (+0.09), much the same as what we see in adults. The children are unhappier the longer they are in the school system (we will look at this in more detail later).

Unlike adults, relative wealth has a non-significant and small effect on childhood happiness.

A possible reason for this is that the wealth question is poorly understood by children. Alternatively, there really is little relation at this age. One possibility to explore with richer data would be that parents manage to shield children from their own feelings about their relative wealth; keeping the rat-race away from their children when they are young.

In terms of our introductory motivation around Richard Easterlin’s 2001 theory of how relative comparisons affect the national income-happiness relationship, our second main finding is thus that relative considerations are not yet that important for teenagers. That is, not amongst teenagers from within a relatively wealthy group that are all sufficiently well-to-do that their school has excursions to visiting exhibitions. Still, taken at face value, it would mean that Richard’s story of disappointment with the disconnect between anticipated income trajectories and anticipated benchmarks are unlikely to be very relevant for young teenagers under 15-years. If such a dynamic is important, it is important in later life, perchance when individuals start earning money themselves.

Adding personality to the specification in Table 18.5 (specification 1b.), we see that extraverted children are happier whilst children with low emotional stability are less happy. We get an unexpected result for conscientiousness. For adults in the Australian socio-economic panel data (HILDA), conscientiousness has a significant negative effect on overall happiness (−0.33, t-value = 2.22).Footnote 9 For the 9–14 year olds in the ‘Smart Train’ data we get an opposite effect (0.066, t-value 2.85). Unlike adults, Australian children who exhibit conscientious behaviours (orderly, systematic, efficient, neat, organised, and efficient) are happier, perchance because the rewards for such behaviour are higher for school children than for adults.

If we now also add domain factors to the demographics (Table 18.6, specification 18.2e), we can see that the effect from the natural environment domain factorFootnote 10 is non-significant, whilst, as expected, the interaction with friends and school environment domains both have a significant effect on childhood happiness.

3.4 Decomposing Changes in Life Satisfaction

Many of the factors that affect life satisfaction, such as gender and personality, are constant or change little over time. The main areas that change over time for these school children are the three main life satisfaction domains, meaning we focus on Specification 2c of Table 18.6.

There is a large decline in the magnitude of these domain factors as the children move from one grade to the next. Between grade 5 and grade 10 the average for the interaction with friends domain declines from 4.21 in grade 5 to 3.92 in grade 8 then rises to 4.08 by the end of grade 10. The average of the school environment domain drops from 3.97 in grade 4 to 5 and continues to drop all the way to 3.24 in grade 10.

To see how much these changes in domain satisfactions can help explain the differences in life satisfaction between children of different school grades; we employ a standard decomposition of the difference in aggregate life satisfaction (LS) levels:

Where the childhood life satisfaction domain factors are:

and the school grade transition is from a lower (l) to the next higher school grade (l + 1):

This decomposition shows the predicted life satisfaction difference across grades due to changes in domain factors. The formula shows the predicted difference between grade 4 and 9, but an analogue formula holds for the difference between any pair of grades.

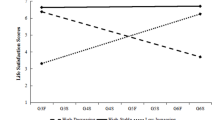

Figure 18.4 shows the predicted changes in childhood happiness as children move through the state school system (grades 4–7) and then transfer to high school (grades 8–9).Footnote 11

This figure shows the predicted change from year to year due to changes in particular domain factors, which means one should add them up to arrive at a cumulative predicted change. Looking at Fig. 18.4 we see the negligible childhood happiness change arising from the non-significant natural environment domain factor (dotted line), less than a 0.012 happiness unit decline (−0.1%) if we add them up across these years. However, the predicted happiness change from the other two factors is both significant and large: when accumulated, the school environment and interaction with friends domains account for 44% (−0.39) of the −0.88 unit fall in childhood happiness for 9 to 14 year-old Australians we saw in the raw data depicted in Figs. 18.2 and 18.3.

Examining how each factor affects childhood happiness as the children progress through the school system, we see that the predicted change in childhood happiness arising from the interaction with friends domain (Fig. 18.4 dashed line) is −0.15 units as the children transition from grades 4–5; the predicted happiness change is almost zero (−0.02) as the children move from grades 5–6, and; there is an even smaller predicted positive change (+0.011) as the children transition through the last grades (6–7) in the lower grade school, potentially reflecting that this is their best year in terms of friendships.

Australian children are often not sent to their local high school but enrolled in public or private high schools that may be many kilometres from the lower grade school that a child attended. This may be a factor in the small (−0.03) decrease in life satisfaction as children move to high school (from grade 7–8). The big drop in happiness (−0.15) comes when the children transition to high school though, driven entirely by a marked drop in the school environment but not the interaction with friends.

Cumulatively, the largest predicted negative change in childhood happiness (−0.31) comes from the school environment, mainly occurring in the transition from grade 4–5 and from grade 8–9.

In terms of the Easterlin theory of income comparisons, these results suggest that other factors play their own role in declining happiness when young: puberty and perchance the increased pressures of school and society that are piled on during high school reduce happiness amongst children. Note though that even our 15-year old Queensland children are very happy compared to almost any group of adults anywhere in the world, leaving plenty to scope for income-comparison disappointments later in life to drag them down!

Finally, we address the third Easterlin-relevant component we want to answer with our data: do kids have unrealistic aspirations or beliefs and do they change in any way over time?

We asked about a particular form of high expectations and naivety: belief in magic. Table 18.6 lists the questions (q6, 7, 8, & 10) which we added together to arrive at a 0–12 index. We included them to capture something that many of us believed in as children, the magic in our lives (Woolley et al. 1999). In our results we see the expected the significant decline (F = 15.66 p = 0.0001) in magical beliefs for both females & males (F = 2.49, p = 0.0309) as the kids age (Fig. 18.5). The effect of magic on happiness is positive (t = 0.019, p = 0.45) but non-significant, and, reducing in age (t = −0.14, t = −.1.57).

We saw earlier that 98% percent of the kids did not think it was OK to throw garbage in a river, whilst only 65% of their parents though so, an indication that updating takes place on that later in life. We then look at the sum of the survey questions listed in Table 18.6 on the Natural Environment. We see that the kids’ attitude to the environment does not significantly change by age (F = 1.93, p = 0.0920), but on average girls show significantly (F = 4.47, p = 0.0351) more concern for the environment than the boys (this result is consistent with recent research by Tranter and Skbris (2011). While kids may be concerned for the natural environment it does not have a significant independent effect on the happiness of the kids in our sample (Table 18.6, specification 2c, Table 18.7) (Fig. 18.6).

Another factor we examined was fairness, the impartial and just treatment of behaviour without favouritism or discrimination. Our fairness factor is the sum of the following three question, each measured on a 5-point Likert scale:

-

1.

Imagine you are hiking in a remote desert. Only 10 bottles of water are available from a shop for $1 each. On a very hot day 20 hikers want to buy water. Is it fair if the shopkeeper makes everybody wait in line for their turn to buy water?

-

2.

Is it fair if the shopkeeper flips a coin to decide if you will be sold a bottle of water? (reverse coded)

-

3.

Is it fair if your hero buys all the water for $1 per bottle and sells it according to his/her own judgement? (reverse coded)

Looking at Fig. 18.7, we see no significant difference between the fairness attitudes of girls or boys (F = 0.00, p = 0.9445) nor was there any difference across ages (F = 0.85, p = 0.517 5).

However, when we look at the distribution of response for questions 2 & 3 that refer to the shopkeeper interfering in the supply and price of water we see a very emotive response by the kids. 85% of the kids said it was probably or completely unfair for the shopkeeper to monopolise the price of water or interfere in who was supplied water. It would appear that kids have strong expectations of how markets should operate, even at a young age. Fairness had a positive but non- significant effect on the kid’s happiness (0.033, t = 0.71).

In short, we find clear evidence for the idea that kids aged 9–15 are highly idealistic and naïve, but only become less naïve in this age range about the subject of magic.

We can mention that we had a quick look at changes amongst the 85 individuals in the HILDA aged 15–18 (compared to the rest, analysed in Headey and Wooden 2004). When Headey and Wooden (2004) looked at the effect of asset income on happiness for all ages in the HILDA, it is significantly positive, but when we ourselves look at asset income for ages 15 to 18 in the HILDA the asset income effect is still positive but non-significant at the 5% level. On top of this, in our Smart Train data, most kids (79%) thought their wealth was the same as those in their neighbourhood. Combined, this suggests that relative wealth comparisons are not yet that important for Australian children under 18 and that concerns for relative wealth become larger afterwards, i.e. when they also lose their naivety about fairness, and the environment.

4 Conclusions and Discussion

This paper contributed to our understanding of lifetime happiness by extending our view of happiness back to childhood. We developed an Internet-based happiness survey for 9 to 14-year-old Australian children. Analysis of the collected data with a model of childhood happiness revealed a large decline in happiness (−0.88 on a 0–10 scale) between the ages of 9 and 14. This solves a puzzle in the existing literature wherein it was previously found that early adolescence was marked with low school environment and higher rates of depression (Hirsch and Rapkin 1987; Huebner et al. 2000), but where there was not yet a clear finding that global life satisfaction levels decreased accordingly (Heubner and Diener 2012).

Another finding is that conscientious children are markedly happier, whilst we found for data amongst adults that the conscientious are less happy. Importantly, there was no found effect of relative wealth, whereas that factor is amongst the most important ones for adults. The kid’s view of family wealth appears to be much removed from reality; 79% of the kids said their family wealth was the same as other families. This is very different from what we see in the Australian 2013–2014 wealth distribution data, where 53% of the wealth is in the top two percentiles (ABS 2015). Our wealth result might indicate that parents within the relatively rich demographic we have in our survey are successful in not transferring their own feelings about their relative wealth on to their children, effectively shielding them from the status race.

With other factors though, the determinants of child happiness were the same as those of adult happiness: girls were happier; the more religious were happier; and the more extraverted were happier.

When we decomposed the changes in life satisfaction amongst children we found that some (44%) of that change was attributable to worsening domain factors. Worsening of the school factors alone could explain 30% in the drop. These school factors include the interaction with the teacher (whether they understand what the teacher says; whether they get bored), items of school success (whether they learn easily, whether they start what they finish), and items of personal effort (whether they work hard, whether they help others and whether they concentrate). These aspects deteriorated markedly in our data from 9 to 10 years of age and 13 to 14 years of age.

What turned out to be unimportant for changes in life satisfaction was their social interaction (number of friends), as this did not decrease over time, nor whether the children were aware of environmental problems.

As to the main questions we started out with pertaining to Richard Easterlin’s thoughts on happiness decline over age and the role of income comparisons therein, we end with 3 tentative conclusions from our study:

-

Richard’s hypothesised decline in happiness over age already starts at age 9, but, is particularly pronounced in the transition to high school.

-

Children aged 9–15 have no trouble answering questions on relative wealth, but unlike our own expectations, these relative comparisons were largely irrelevant for happiness in this age group for this social demographic. Disappointment in income-comparisons simply do not appear yet to play a role, perchance because these children do not have to work for a living. The relative unimportance of relative wealth persists at least till 18.

-

These children are highly idealistic, with 99% saying pollution of the waters flowing to another state is bad, whilst only 45% of their parents’ generation say so. Similar naivety is found when it concerns fairness and magic, and only in the case of the belief in magic do we see a significant drop before the age of 15. So we do indeed find strong evidence for highly unrealistic expectations and beliefs amongst children, indeed at the same time as their happiness levels are extremely high.

Let us end with thanking Richard for his massive contributions to social science. Our paper does not quite prove him right on every point of his 2001 theory as it pertains to children, but at least we find them able to answer relative income questions and that the pressures of life do drag them down a bit in teenage years and much stronger after that. We cannot quite confirm his theory to be right on all counts, because our data is simply not rich enough for that, but, our findings are in line with Richard’s thinking.

Notes

- 1.

An important question is of course why countries are so obsessed with higher national incomes. In Frijters and Foster (2013) it is argued that relative standing between groups is a prime motivator for the existence and cohesion of the nation state. This is partially from the (somewhat mistaken) belief of the population that it will make them happier, but it is also connected with military might (money can buy weapons) and hence with relative power.

- 2.

The HILDA data was extracted using the Add-On package PanelWhiz v3.0 (Nov 2010) for Stata. PanelWhiz was written by Dr. John P. Haisken-DeNew (john@panelwhiz.eu). The PanelWhiz generated DO file to retrieve the HILDA data used here and any Panelwhiz Plugins are available upon request. Any data or computational errors in this paper are my own. Haisken-DeNew and Hahn (2006) describes PanelWhiz in detail.

- 3.

This paper uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA 2013). The HILDA Project was initiated and funded by the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (MIAESR). The findings and views reported in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either FaHCSIA or the MIAESR. We thank FaHCSIA & the Melbourne Institute director, Professor Deborah Cobb-Clark, and her staff for making the data available.

- 4.

More information on the ‘Smart Train’ is at: http://www.abc.net.au/local/photos/2008/05/09/2240428.htm

- 5.

After the 3-week survey response period, the Queensland Government, Department of Innovation, Tourism Industry Development randomly selected a student who received an individual prize of an Apple iPod and their school received $1000 to spend on science resources.

- 6.

In middle childhood, children get bored and fail to complete surveys with too many questions, they also require literally worded questions that they can understand (de Leeuw et al. 2004).

- 7.

The HILDA socio-economic panel surveys adults with 5–8 questions per personality trait.

- 8.

Overall, regional children showed less concern for the environment; the average of the Natural Environment Life Satisfaction Domain factor for urban children was 14% higher than for regional children (Table 18.6).

- 9.

The personality traits are scaled 1–7 in the HILDA & 1–30 in this paper; the HILDA coefficient has been rescaled; 1–30. Regression tables relevant to this are available on request.

- 10.

If we look at the effect from the individual ‘natural environment’ questions in Table 18.7, we see that only one environment question (q17) had a significant effect on happiness. Children who perceived their family as wealthier than their friend’s families are more likely to discuss environmental issues within their family (q17 was strongly positively correlated with wealth).

- 11.

Post this study, the transition to high school in Queensland now occurs in grade 7.

References

ABS. (2010). 4102.0 – Australian social trends, June 2010 (Previous ISSUE Released at 11:30 AM (CANBERRA TIME) ed.): Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2015). 6523.0 – Household income and wealth, Australia, 2013–14E. Released at 11:30 am (CANBERRA TIME) 4 September 2015: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Antaramian, S. P., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2008). Adolescent life satisfaction. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57(1), 112–126.

Antaramian, S. P., Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., & Valois, R. F. (2010). A dual-factor model of mental health: Toward a more comprehensive understanding of youth functioning. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(4), 462–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01049.x.

Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., Rabasca, A., & Pastorelli, C. (2003). A questionnaire for measuring the Big Five in late childhood. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(4), 645–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00051-x.

Barbaranelli, C., Fida, R., Di Giunta, L., & Caprara, G. V. (2008). Assessing personality in early adolescence through self-report and other-ratings a multitrait-multimethod analysis of the BFQ-C. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 876–886.

Bedin, L. M., & Sarriera, J. C. (2015). A comparative study of the subjective well-being of parents and adolescents considering gender, age and social class. Social Indicators Research, 120(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0589-7.

Bruhin, A., & Winkelmann, R. (2009). Happiness functions with preference interdependence and heterogeneity: The case of altruism within the family. Journal of Population Economics, 22(4), 1063–1080.

Campbell, M. E., & Eggerling-Boeck, J. (2006). What about the children? The psychological and social well-being of multiracial adolescents. Sociological Quarterly, 47(1), 147–173.

Carlsson, F., Lampi, E., Li, W., & Martinsson, P. (2014). Subjective well-being among preadolescents and their parents – Evidence of intergenerational transmission of well-being from urban China. Journal of Socio-Economics, 48, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2013.10.003.

Cheng, H., & Furnham, A. (2004). Perceived parental rearing style, self-esteem and self-criticism as predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(1), 1–21.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 95–144.

Cummins, R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research, 38(3), 303.

de Leeuw, E., Borgers, N., & Smits, A. (2004). Pretesting questionnaires for children and adolescents. In S. Presser (Ed.), Methods for testing and evaluating survey questionnaires (pp. 409–452). Hoboken: Wiley.

Dear, K., Henderson, S., & Korten, A. (2011). Well-being in Australia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 37(11), 503–509.

del Barrio, V., Carrasco, M. Á., & Holgado, F. P. (2006). Factor structure invariance in the Children’s Big Five Questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 22(3), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.22.3.158.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575.

Diener, E., & Suh, M. E. (1998). Subjective well-being and age: An international analysis. In K. W. Schaie & M. P. Lawton (Eds.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (Focus on emotion and adult development) (Vol. 17, pp. 304–324). New York: Springer.

Dockery, A. M. (2005). The happiness of young Australians: Empirical evidence on the role of labour market experience. Economic Record, 81(255), 322–335.

Donnelly, D., Mercer, R., Dickson, J., & Wu, E. (2009). Australia’s Farming Future Final Market Research Report. Understanding behaviours, attitudes and preferences relating to climate change. Sydney: Instinct and Reason.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Subjective well-being and economic analysis: A brief introduction. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 45(3), 225–226.

Easterlin, R. A. (2005). A puzzle for adaptive theory. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 56(4), 513–521.

Ebner, A. (2008). ‘Nest-leaving’ in Osterreich: Was beeinflusst die Wohnentscheidung junger Erwachsener? (Nest-Leaving in Austria: What Determines Young Adults’ Housing Decisions? With English summary). Wirtschaftspolitische Blatter, 55(2), 407–423.

ECHP. (2015). European community household panel. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-community-household-panel

Flouri, E. (2004). Subjective well-being in midlife: The role of involvement of and closeness to parents in childhood. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(4), 335–358.

Fogle, L. M., Huebner, E. S., & Laughlin, J. E. (2002). The relationship between temperament and life satisfaction in early adolescence: Cognitive and behavioral mediation models. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(4), 373–392.

Fordyce, M. W. (1988). A review of research on the happiness measures: A sixty second index of happiness and mental health. Social Indicators Research, 20(4), 355–381.

Forste, R., & Moore, E. (2012). Adolescent obesity and life satisfaction: Perceptions of self, peers, family, and school. Economics and Human Biology, 10(4), 385–394.

Frijters, P., & Foster, G. (2013). An economic theory of greed, love, groups and networks. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. (2004). Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real income and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. American Economic Review, 94(3), 730–740.

Frijters, P., Johnston, D. W., & Shields, M. A. (2011). Destined for (Un)happiness: does childhood predict adult life satisfaction? (IZA discussion paper series). Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Gilman, R., & Huebner, E. S. (1997). Children’s reports of their life satisfaction: Convergence across raters, time and response formats. School Psychology International, 18(3), 229–243.

Gilman, R., & Huebner, E. S. (2000). Review of life satisfaction measures for adolescents. Behaviour Change, 17(3), 178–195.

Gilman, R., & Huebner, S. (2003). A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), 192–205.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”, The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1215–1229.

Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Hahn, M. (2006). PanelWhiz: A flexible modularized stata interface for accessing large scale panel data sets. Mimeo. Retrieved from http://www.panelwhiz.eu

Haranin, E. C., Huebner, E. S., & Suldo, S. M. (2007). Predictive and incremental validity of global and domain-based adolescent life satisfaction reports. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 25(2), 127–138.

Headey, B., & Wooden, M. (2004). The effects of wealth and income on subjective well-being and ill-being. Economic Record, 80, S24–S33.

Heubner, E. S., & Diener, C. (2012). Research on life satisfaction of children and youth: Implications for the delivery of school-related services. In M. Eid (Ed.), The science of subjective wellbeing (pp. 376–392). New York: Guildford Press.

HILDA. (2013). The household, income and labour dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, release 11. Retrieved August 21, 2013, from https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/hilda

Hirsch, B. J., & Rapkin, B. D. (1987). The transition to junior high school: A longitudinal study of self-esteem, psychological symptomatology, school life, and social support. Child Development, 58, 1235–1243.

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Correlates of life satisfaction in children. School Psychology Quarterly, 6(2), 103–111.

Huebner, E. S. (1994). Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 149–158.

Huebner, E. S. (1995). The Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale: An assessment of psychometric properties with black and white elementary school students. Social Indicators Research, 34(3), 315.

Huebner, E. S., Gilman, R., & Laughlin, J. E. (1999). A multimethod investigation of the multidimensionality of children’s well-being reports: Discriminant validity of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Social Indicators Research, 46, 1–22.

Huebner, E. S., Drane, W., & Valois, R. F. (2000). Levels and demographic correlates of adolescent life satisfaction reports. School Psychology International, 21(3), 281–292.

Huebner, E. S., Valois, R. F., Paxton, R. J., & Drane, J. W. (2005). Middle school students’ perceptions of quality of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(1), 15–24.

Johnston, D. W., Nicholls, M. E. R., Shah, M., & Shields, M. A. (2009). Nature’s experiment? Handedness and early childhood development. Demography, 46(2), 281–301.

Lee, W.-S., & Oguzoglu, U. (2007). Income support and stigma effects for young Australians. Australian Economic Review, 40(4), 369–384.

Leiser, D., & Beth Halachmi, R. (2006). Children’s understanding of market forces. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27(1), 6–19.

Levin, K., Torsheim, T., Vollebergh, W., Richter, M., Davies, C., Schnohr, C., Due, P., & Currie, C. (2011). National income and income inequality, family affluence and life satisfaction among 13 year old boys and girls: A multilevel study in 35 countries. Social Indicators Research, 104(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9747-8.

Levin, K. A., Dallago, L., & Currie, C. (2012). The association between adolescent life satisfaction, family structure, family affluence and gender differences in parent-child communication. Social Indicators Research, 106(2), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9804-y.

Lischetzke, T., & Eid, M. (2006). Why extroverts are happier than introverts: The role of mood regulation. Journal of Personality, 74(4), 1127–1162.

LSAY. (2012). The longitudinal surveys of Australian youth. Retrieved April 2, 2012, from National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER). http://www.ag.gov.au/cca

Moore, J. C., Stinson, L. L., & Welniak, E. J. (2000). Income measurement error in surveys: A review. Journal of Official Statistics, 16(4), 331–361.

Moore, P. M., Huebner, E. S., & Hills, K. J. (2012). Electronic bullying and victimization and life satisfaction in middle school students. Social Indicators Research, 107(3), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9856-z.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Diederen, R. (2005). Psychometric properties of the Big Five Questionnaire for Children (BFQ-C) in a Dutch sample of young adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(8), 1757–1769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.11.018.

Natvig, G. K., Albrektsen, G., & Qvarnstram, U. (2003). Associations between psychosocial factors and happiness among school adolescents. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 9(3), 166–175.

Powdthavee, N., & Vernoit, J. (2013). Parental unemployment and children’s happiness: A longitudinal study of young people’s well-being in unemployed households. Labour Economics, 24, 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2013.09.008.

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press.

Seligson, J., Huebner, E., & Valois, R. (2005). An investigation of a brief life satisfaction scale with elementary school children. Social Indicators Research, 73(3), 355–374.

SoE. (2011). In A. S. o. t. E. Committee (Ed.), State of the environment 2011. Canberra: Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities.

Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2006). Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? Journal of Socio-Economics, 35(2), 326–347.

Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2012). Recent developments in the economics of happiness: A selective overview (IZA Discussion Series). Institute for the Study of Labour. Bonn, Germany. Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp7078.pdf

Suldo, S. M., Riley, K. N., & Shaffer, E. J. (2006). Academic correlates of children and adolescents’ life satisfaction. School Psychology International, 27(5), 567–582.

Tranter, B., & Skbris, Z. (2011). Attitudes toward global warming, climate change and other environmental issues among young Queenslanders. eSpace, The University of Queensland. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:269694

Tsang, L. L. W. (2003). the effects of children, dual earner status, sex role traditionalism, and marital structure on marital happiness over time. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 24(1), 5–26.

Ulker, A. (2008). mental health and life satisfaction of young Australians: The role of family background. Australian Economic Papers, 47(2), 199–218.

Wessman, A. E., & Ricks, D. F. (1966). Mood and personality. Oxford: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

White, N. P. (2006). A brief history of happiness. Malden/Oxford: Blackwell Pub.

Wilson, W. R. (1967). Correlates of avowed happiness. Psychological Bulletin, 67(4), 294–306.

Woolley, J. D., Phelps, K. E., Davis, D. L., & Mandell, D. J. (1999). Where theories of mind meet magic: The development of children’s beliefs about wishing. Child Development, 70(3), 571–587.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Markus Schaffner of the Queensland Behavioural Economics Group (QuBE); Leesa Watkin (QUT Smart Train Project Manager), and; Annie Harris (Department of Innovation, Tourism Industry Development, Queensland State Government) for their considerable technical, organisational, and financial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix A: Survey Questions

1.2 Appendix B: Descriptive Statistics

1.3 Appendix C: Regression Results

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Beatton, T., Frijters, P. (2019). Happiness Amongst Teens in Australia. In: Rojas, M. (eds) The Economics of Happiness. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15835-4_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15835-4_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-15834-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-15835-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)