Abstract

The research summarized here provides encouraging evidence that the right to protest against war is a widely accepted global norm. Very few of the participants in the seven regions of the world that were studied explicitly disagreed with that right. Active agreement with that right ranged from close to eight in ten in East Asia and Russia and the Balkans, to around nine in ten in South and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and the UK/Anglo region and was highest in Western Europe and Latin America. The right to protest was justified most widely by the national laws that protect that right in most regions, although study participants in Latin America, South and Southeast Asia, and East Asia tended to offer the justification that protest is a universal human right. Another theme frequently expressed in agreement with the right to protest was the moral responsibility to act, particularly by men in the Middle East and persons who had taken part in antiwar protests in Russia and the Balkans. The suppression of antiwar protests was widely condemned, and most study participants stated that they would actively oppose the beating of protestors, e.g., by asking the government to protect them and by calling the suppressive acts to the attention of mass media. The lowest level of active opposition to the use of violence to suppress antiwar protests was expressed in Africa, where study participants cited helplessness as a justification for their lack of engagement. Generally, support for the right to protest and opposition to the suppression of protest were greater among women than men. Overall this research shows that antiwar protests are strongly supported worldwide, both as a legal and human right and, particularly among those who engage in protest, as a moral responsibility.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

The previous eight chapters in this section have analyzed the responses of participants from Western Europe, the UK/Anglo region (the United Kingdom and its former Anglophone colonies excluding India), Russia and the Balkan Peninsula, the Middle East and Gulf States, Africa, Latin America, South and Southeast Asia, and East Asia concerning the right to protest. This chapter considers the extent to which the participants from these eight regions have similar or different viewpoints regarding the right of individuals to protest against war and in favor of peace, as well as what they would want to do if they saw police suppressing peaceful protestors by beating them.

As explained in earlier chapters, responses to the two protest items from the Personal and Institutional Rights to Aggression and Peace Survey (PAIRTAPS; Malley-Morrison, Daskalopoulos, & You, 2006) were coded using a moral disengagement/engagement coding manual developed by members of the Group on International Perspectives on Governmental Aggression and Peace (GIPGAP). The manual was researcher developed using a deductive qualitative analysis approach (Gilgun, 2004) based on work by Albert Bandura (e.g., Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 1996; Bandura, 1999; McAlister, 2000; McAlister, Bandura, & Owen, 2006). It was further refined using grounded theory, which allows thematic categories to emerge from responses (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The first item directs survey respondents to indicate their level of agreement, on a seven-point Likert scale, with the item: “individuals have the right to stage protests against war and in favor of peace” and then to explain the reasoning behind their rating. The second statement poses the scenario: “police are beating peaceful antiwar demonstrators. What would you want to do?”

Moral Disengagement Theory as a Basis for Coding

Albert Bandura’s theory (2002) of moral disengagement posits that individuals develop ethical standards that guide social conduct, promote self-esteem and worth, and protect against self-sanction, as long as the individuals act in accordance with these self-imposed standards. There are times, however, that the self-regulation of conduct is suspended as the person feels that ethical standards no longer apply to the situation, thereby diverting moral reactions away from reprehensible conduct. According to Bandura, the socio-cognitive processes that allow such diversions are best conceptualized as forms of moral disengagement. Conversely, when acting in accordance with their moral standards, individuals exhibit moral engagement.

In his theory, Bandura has identified several sociocognitive mechanisms by which self-condemnation for inhumane behavior is disabled. These mechanisms served as the basis for many of the major coding categories in our manual. Although much less developed, his theory of moral engagement shaped several of our major coding categories as well.

Bandura (2002) theorized that moral engagement is linked to moral agency. He identified two forms of moral agency: (a) inhibitive and (b) proactive. When a person refuses to act in an immoral manner and instead acts in accordance with his or her moral standards, he or she is exhibiting inhibitive moral agency. Proactive moral agency is exhibited by behaving morally, even when pressured to behave immorally. While exhibiting this form of moral agency, a person feels responsible for others and acts accordingly. It is important to note that when coding participant’s responses, coders were not passing judgment on the respondent’s morality but rather categorizing his or her responses into thematic categories informed by the theory.

The Right to Protest Coding Categories

The first major anti-protest category was also the most general category: general protest intolerance. This category, the only major category not based on Bandura’s theory, was used to code responses that rejected an individual right to protest but failed to provide any rationale for the disagreement. Pseudo-moral justification encompassed responses that argued that protesting is harmful to society. Its subcategory, supporting troops or the government, was used to code responses that emphasized patriotism. The third major category, negative labeling, captured responses that used discrediting labels to describe protesting. Another major category, disadvantageous comparison, was used to categorize responses that compared protesting to some other behavior seen as more desirable, such as obedience. Responses that rejected any individual responsibility for protesting against injustice or aggression were coded for a denial of personal responsibility. If responses emphasized perceived negative consequences of protesting, they were coded for distorting consequences. The major category of dehumanization had two subcategories: (a) dehumanization of the protestor, for responses that attributed demonic qualities to the protestor, and (b) dehumanization of the targets of war, for responses that attributed demonic qualities to the victims of war. Finally, the major category attribution of blame also had two subcategories: (a) protestors as agents, in which protestors were seen as blameworthy for protesting when they had no right to do so, and (b) targets of war, in which individuals were portrayed as having no right to protest because any country under attack deserved its fate.

Our pro-protest coding categories were created as complements to the anti-protest category. The first major category, general pro-protest, was used to code responses that agreed with the right to protest but failed to provide a rationale for the agreement. The second major category, social justification, was for responses arguing that protest helps society to develop. This category had two subcategories: (a) peace as a goal, which encompassed responses that stated peace is the goal of protesting, and (b) awareness of negative consequences, which encompassed responses that mentioned consequences that could arise from inaction. Responses stating that it is the obligation of individuals to protest were coded for moral responsibility. This category had three subcategories: (a) civic duty, which was used to code responses that stated protest is one’s obligation as a citizen; (b) nonviolent, which was used to code responses that stated people have the right to stage peaceful protests; and (c) law abiding, which was used to code responses that stated protests must be done in accordance with the law. The final major pro-protest category was humanization. Its first subcategory, reciprocal right, was for responses asserting that our actions reflect that stated if people have the right to go to war, they should have the right to protest that as well. The second subcategory, human rights, was used to code responses indicating that protesting is an inherent right of all individuals. Human rights had two subcategories: (a) it should be a right, designed to capture responses stating that if protesting is not a right in some countries, it should be one, and (b) international law, which was used to code responses that referred to protest as a right guaranteed by international human rights agreements. The final subcategory of humanization, socially sanctioned rights, captured responses that said protesting is a right that stems from national law.

It is important to note that (a) the survey was not designed specifically to assess moral disengagement and engagement; (b) the sample was not representative; and (c) we are not characterizing people or regions as being engaged or disengaged. Rather, in describing the themes identified in the qualitative responses, we use the terms “protest intolerant” or “anti-protest” and “protest tolerant” and “pro-protest,” instead of “moral disengagement” and “moral engagement.” Our coding categories are informed by Bandura’s theory, and the responses in those categories fit well with his theory, but we cannot assume that the responses are valid representations of the sociocognitive mechanisms he posits. Additionally, the results have been interpreted carefully and should not be generalized to the general public.

Patterns of Responses for Individuals’ Right to Protest

Across all of the regions, very few responses were coded for anti-protest sentiments. South and Southeast Asian and the UK/Anglo responses accounted for the highest percentage of these viewpoints, at 5% of all responses. Four percent of responses from the Middle Eastern sample rejected an individual right to protest, while 3% of all the responses from Russia and the Balkan Peninsula and Africa rejected this right. Finally, 2% of the East Asian responses and 1% of the Western European and Latin American responses did not agree that individuals have a right to protest against war and in favor of peace.

In general, responses rejecting the right to protest were coded into two categories: (a) distorting consequences and (b) pseudo-moral responsibility. Only in Western Europe were most anti-protest responses coded into a different category, denial of personal responsibility. Distorted consequences of protesting were most often seen in the UK/Anglo, the Middle Eastern, African, and South and Southeast Asian responses. In the East Asian sample, distorting consequences and pseudo-moral responsibility reasoning were tied at 1% of all the anti-right to protest responses. Thinking consistent with pseudo-moral responsibility was most often seen in the Latin American and the Russian and Balkans responses.

In the UK/Anglo region, Russia and the Balkan Peninsula, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and South and Southeast Asia, several responses were coded for a general disagreement with individuals’ right to protest. Interestingly, there were no responses coded into two categories: (a) dehumanization of the targets of war and (b) blaming the targets of war across all of the regions. Reasoning consistent with every other coding category was identified in the responses of at least one of the regions.

The vast majority of responses to individuals’ right to protest supported this right. At least 82% of all responses were coded for pro-protest themes in these regions. Ninety-seven percent of all Latin American responses demonstrated this type of thinking, with Western Europe following closely with 95% of all responses supporting the right to protest against war. Responses from the Middle Eastern and African sample agreed with the right to protest at a rate of 89% of all responses. Eighty-eight percent of South and Southeast Asian and the UK/Anglo responses were coded for the pro-protest categories, 84% of the Russian and Balkans responses, and 82% of the East Asian responses.

As was true with the anti-protest responses, there was little variation across regions in the most popular reasons given for why individuals have the right to protest. Reasoning consistent with two of the humanization categories, human rights and socially sanctioned rights, was most often seen in the responses. Responses that said protesting is protected by national law and is therefore a socially sanctioned right were most often coded for in the Western European, the UK/Anglo, and the Middle Eastern samples, 27%, 25%, and 16% of all responses, respectively. In Latin America, this type of reasoning was seen in 17% of all responses, which was the same percentage found for human rights responses. In addition to Latin America, protesting was seen as an inherent human right in responses from South and Southeast Asia and East Asia. Africa was the only region where the largest percentage of responses were coded for moral responsibility, with 14% of responses coded into this category. Examples of moral responsibility were seen in the responses from all of the other regions but at a lesser percent. In the Russian and Balkans sample, the most commonly coded category was general agreement with the right.

Additionally, at least 8% of responses in each of the regions specified that nonviolent protesting is a right that everyone shares. Still other responses were coded for peace as a goal of protesting in each of the regions. No responses from any of the regions showed reasoning that protesting is a right protected by international law. Every other category was identified in responses in at least one of the regions.

The Role of Demographic Variables in Viewpoints Concerning Individuals’ Right to Protest

Respondents provided demographic information in addition to their responses to the PAIRTAPS. The demographic responses allowed us to determine the extent to which the frequency of particular forms of reasoning that were tolerant or intolerant of the right to protest varied as a function of gender, military service, having a relative in the military, and involvement.

Gender

Reasoning concerning individuals’ right to protest varied as a function of gender in every region except for Latin America. Proportionately more women than men from East Asia gave responses coded for one or more of the pro-protest coding categories. In Russia and the Balkan Peninsula and South and Southeast Asia, proportionately more women than men gave social justifications for the right to protest, such as protesting helps society to develop. Proportionately more African men than women showed an awareness of the negative consequences of not protesting against war and in favor of peace. Finally, in the Middle East, proportionately more men than women saw protesting as one’s moral responsibility. Conversely, proportionately more women than men from Africa provided pro-protest reasoning coded for moral responsibility. Proportionately more women than men from the UK/Anglo region and Western Europe stated that for protests to be a right, they must be nonviolent. Finally, in Russia and the Balkans, Africa, and South and Southeast Asia, proportionately more men than women saw protesting as a socially sanctioned right given to citizens by their government.

Military Service

Military service as a predictor of responses was seen in fewer cases than gender. The only significant anti-protest result was found for military service: in Russia and the Balkans, proportionately more military respondents than civilian respondents gave responses coded for the pseudo-moral reasoning categories. In East Asia, proportionately more respondents without military experience than their counterparts responded with reasoning coded for one or more of the pro-protest categories. Proportionately more respondents in the military than not in the military stated that protesting is a socially sanctioned right in Russia and the Balkans and the Middle East. Conversely, proportionately more nonmilitary respondents than military respondents from Russia and the Balkan Peninsula gave social justifications as the reason why individuals have the right to protest. Finally, in Western Europe, proportionately more civilians than their counterparts saw protesting as a right if it is done nonviolently.

Relative’s Military Service

Group differences based on a relative’s military service were found on only four of the right to protest coding categories. In South and Southeast Asia, proportionately more respondents with a relative in the military gave responses that were identified as generally pro-protest in nature as compared to their counterparts. Similarly, proportionately more African respondents with a relative in the military as compared to those without one showed an awareness of negative consequences in their responses. Proportionately more respondents without a relative in the military said that protests must be nonviolent than respondents with a relative in the military from Western Europe. In the UK/Anglo region and South and Southeast Asia, proportionately more respondents without a relative in the military than their counterparts stated that protesting is an inherent human right that all individuals share. Finally, in Russia and the Balkan Peninsula and the UK/Anglo region, proportionately more respondents with at least one relative in the military as compared to respondents without one saw protesting as a socially sanctioned right.

Protest Participation

Protest participation proved to be a fairly robust contributor to responses from Russia and the Balkan Peninsula, Latin America, and the UK/Anglo region. Proportionately more protestors than non-protestors from Russia and the Balkans saw protesting as one’s moral responsibility. The opposite result was true in Latin America: proportionately more non-protestors than protestors stated that protesting is one’s moral responsibility. Furthermore, in Latin America, proportionately more protestors than non-protestors stated that protesting is a human right that everyone shares. In the UK/Anglo region, proportionately more non-protestors than protestors stated that nonviolent protesting is a right. Conversely, proportionately more protestors than non-protestors from the UK/Anglo region saw protesting as one’s civic duty. Finally, also in the UK/Anglo region, proportionately more protestors than non-protestors said that if protesting is not a right in a country, it should be one.

Police Beating Peaceful Protestors Coding Categories

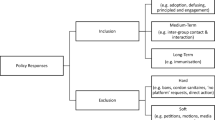

In general, responses to the police beating peaceful protestors were coded into three thematic categories: (a) pro-social agency, (b) antisocial agency, and (c) lack of agency.

The first major theme, pro-social agency, captured responses that referenced actions or feelings that would be beneficial to the protestors, such as finding ways to end the police actions permanently. Judgment of police, the first pro-social agency category, was used to code responses that generally disagreed with the police’s actions. The second category was personal initiative, which encompassed responses indicating a desire to stop the police but not specifying how to do so. This category had three subcategories, all of which indicated a goal of ending the beatings: (a) activism, (b) personal understanding, and (c) other solutions. The third pro-social category was institutional initiative. Responses coded into this category called for an unspecified institution to handle the situation. The two subcategories in this category, all of which specified an organization to end the beating, were (a) legal action and (b) government/other entity.

Antisocial agency themes were coded into three major categories: (a) support for police, (b) unlawful activism, and (c) against the demonstrators. Responses expressing support for the police aggression were coded for support for police. Unlawful activism was designed to categorize responses indicating that the respondent would want to harm the police. If responses supported taking actions against the demonstrators, they were coded as action against the demonstrators.

The first coding category under lack of agency was lack of initiative. This category applied to responses indicating that the respondent would not do anything if he or she saw police beating protestors. The other category, helplessness, encompassed responses that said the respondent would not be able to do anything useful in this situation.

Patterns of Responses for Police Beating Protestors Hypothetical Situation

A majority of responses across the regions were coded for the pro-social agency constructs. Responses from Western Europe, Latin America, and South and Southeast Asia had the highest percentage of pro-social agency responses, with 83% of all responses to the scenario coded into these categories. In the other regions, the percentages of pro-social agency responses were 80% for the UK/Anglo region, 76% for East Asia and 75% for the Middle East, 68% for Russia and the Balkan Peninsula, and 58% for Africa.

All of the regions showed high rates of personal initiative. This coding category was the most frequently coded category in every region except for Western Europe. Personal initiative and activism were tied in South and Southeast Asia as the most commonly used forms of reasoning in response to police beating protestors. The most commonly seen response in Western Europe was activism, indicating that the respondents would want to protest against the police violence or report it to the media. All of the pro-social coding categories were identified in responses from every region, except that none of the African responses were coded for personal understanding. Many responses across the regions were coded for expressing an intent to take legal action against the police in this situation.

Antisocial agency was identified in responses at a much lower rate than pro-social agency. Russia and the Balkan Peninsula had the highest frequency of antisocial responses, with 14% of the responses being coded into these categories. The percentages of antisocial responses in the other regions were 12% for East Asia, 11% for the UK/Anglo region, 10% for the Middle East, 8% for South and Southeast Asia, 7% for Western Europe and Africa, and 6% for Latin America.

Unlawful activism was the most common form of antisocial agency identified in all of the regions. Some responses in every region except for Africa were coded for support for the police. Similarly, every region except for Western Europe had responses coded for actions taken against the demonstrators.

The regions differed somewhat in the percentage of responses coded into the lack of agency categories. In Africa, 33% of responses were coded for lack of agency. In the other regions, the percentages of responses coded into the lack of agency category were 14% of all responses from the Middle East, 12% of the responses from Russia and the Balkans, 9% of East Asian responses, 8% of Latin American responses, and 7% of responses from Western Europe, the UK/Anglo region, and South and Southeast Asia. Lack of initiative was the most common lack of agency response in all of the regions. All of the regions also had some responses coded for helplessness but at a much lower frequency.

The Role of Demographic Variables in Viewpoints Concerning a Hypothetical Situation Involving Police Beating Peaceful Protestors

Gender

Across all of the regions except for South and Southeast Asia, gender proved to be a contributor to the frequency of particular themes in response to the police beating protestors scenario. Proportionately more women than men from Latin America and the UK/Anglo region gave responses coded for one or more of the pro-social agency categories. Conversely, proportionately more men than women from Latin America and the UK/Anglo region gave responses coded for one or more of the antisocial agency and lack of agency categories. Additionally, proportionately more men than women from those two regions, East Asia and Africa, projected a lack of initiative in their responses to the hypothetical scenario concerning police beating peaceful protestors. In East Asia and the UK/Anglo region, proportionately more women than men showed an intent to exercise personal initiative to end the beatings in their responses. Proportionately more women than men from Western Europe gave responses that were coded for activism, such as protesting the beatings. In Russia and the Balkan Peninsula, proportionately more women than men stated that they would want to take legal action against the police. Similarly, in the UK/Anglo region, proportionately more women than men gave responses coded for institutional activism. Finally, proportionately more women than men from the Middle East offered reasoning coded for unlawful activism, such as beating the police, in response to this situation.

Military Service

Group differences based on military service were found in responses from only three of the regions. In the Middle East, proportionately more military respondents than civilian respondents gave responses coded for one or more of the pro-social agency categories, specifically including personal initiative and legal action. In the UK/Anglo region, as well as the Middle East, proportionately more nonmilitary respondents than veteran respondents said they would want to engage in some form of activism in their responses to this situation. Another of the pro-social agency themes also varied in relation to military service in the UK/Anglo region: proportionately more respondents in the military than not in the military gave responses saying that they would contact the government or another entity to help in the situation. Proportionately more nonmilitary than military respondents in the Middle East gave responses coded for one or more of the lack of initiative categories. Specifically, proportionately more nonmilitary respondents as compared to military respondents showed a lack of initiative in their responses. In Africa the opposite result was found to be true: proportionately more veterans than civilians gave responses coded for a lack of initiative.

Relative’s Military Service

Very few significant differences were found for the use of these categories as a function of relative’s military service. In Western Europe, proportionately more respondents without a relative in the military as compared to their counterparts displayed personal initiative in their responses. In Africa, proportionately more respondents with a relative in the military as compared to their counterparts displayed activism in their responses. Proportionately more respondents with civilian relatives than veteran relatives from Russia and the Balkan Peninsula gave responses coded for institutional initiative in response to the hypothetical situation. Finally, a significantly greater proportion of African respondents with civilian relatives than respondents with veteran relatives mentioned a desire to take legal action against the police if they beat peaceful protestors.

Protest Participation

In the UK/Anglo region, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia, proportionately more protestors than non-protestors gave responses coded for one or more of the pro-social agency categories. Proportionately more protestors than non-protestors from Russia and the Balkans judged the police critically in their responses. Conversely, proportionately more non-protestors than protestors from the Middle East gave critical judgments of the police in their responses. Proportionately more protestors than non-protestors from South and Southeast Asia showed personal initiative for stopping the beatings in their responses. Additionally, proportionately more protestors than non-protestors from South and Southeast Asia, Russia and the Balkans, and Latin America stated that they would want to engage in some form of activism, such as reporting the polices’ actions to the media. In Russia and the Balkan Peninsula, proportionately more protestors than non-protestors offered other solutions than beating protestors. Proportionately more respondents who had never protested as compared to respondents who had protested from the UK/Anglo region and the Middle East gave responses coded for the antisocial agency categories. Interestingly, proportionately more protestors than non-protestors from the Middle East gave responses with reasoning coded for unlawful activism. Finally, proportionately more non-protestors than protestors from the Middle East, the UK/Anglo region, and Russia and the Balkan Peninsula gave responses coded for the lack of agency coding categories, specifically including the lack of initiative category.

Conclusions

Reflecting on these findings, it is encouraging to find very little disagreement with the right to protest against war and for peace. Some men in Russia and the Balkans cited harm to society as a moral justification for denying the right to protest. Among the extremely small group opposing the right to protest in Western Europe, it is interesting to find that they justify this belief by denying that individuals have the responsibility to take protest. It is extremely encouraging to find that negative labeling, dehumanization, and blame were almost never cited as reasons for opposing the right to protest against war anywhere.

Humanitarian engagement expressed in the form of active agreement with individuals’ rights to protest war and support peace varied from near unanimity in Latin America and Western Europe to around nine in ten in the UK/Anglo region, the Middle East, Africa, and South and Southeast Asia. Lower levels of active support for the right to protest were found in Russia and the Balkans, and East Asia deserves comment, as they suggest that there is a significant minority in these regions that might be willing to see protest rights denied.

The social sanction provided by national laws emerged as the most common form of moral engagement in justifying the right to protest in Western Europe, the UK/Anglo regions, the Middle East, and among members of the military in Russia and the Balkans. Women in that region, Africa and South and Southeast Asia, also tended to cite national laws justifying the right to protest. Interestingly more general human right to protest, rather than the protection of national law, was commonly used to justify support for that right in Latin America, South and Southeast Asia, and East Asia.

It is interesting to note that among those whose level of moral engagement was great enough to lead them to participate in antiwar protests in Russia and the Balkans, the responsibility to take action is the most common justification. The moral responsibility to protest against war was also endorsed by men in the Middle East. Protesters in the UK/Anglo regions cited civic duty to justify their support for the right to protest. Protestors in Latin America expressed their human rights as a justification, while non-protestors there justified support for those who do protest on the basis of their moral responsibility to take part in protests in opposing war and supporting peace.

Responses to the hypothetical question about the suppression of protest showed that the majority of respondents in every country would condemn that action, often citing the intention to be proactively engaged by engaging in protests against suppression, calling for attention from the media, and invoking the responsibility of government institutions to protect protesters. Four in five or more expressed proactive engagement in response to the beating of protesters in all regions, except in East Asia (76%), Russia and the Balkans (68%), and Africa (55%). This suggests that significant social forces may support the suppression of protest in these regions, and it is notable that an expectation of inaction due to perceived helplessness was most commonly expressed in Africa. Active support for the suppression of protest was most common in Russia and the Balkans, but not much less common in the UK/Anglo regions and East Asia. The most common justification for supporting the suppression of protest was the moral utility argument that it was unlawful and potentially harmful to the state.

While these findings are encouraging overall, they point to regions and groups in which there are threats to engagement in support of the right to protest and opposition to the suppression of protest. People in Russia and the Balkans and East Asia show a tendency toward less support for the right to protest and more support for the suppression than people in other regions. Regarding suppression of protest, people in Africa are notably less likely express proactive engagement in the condemnation of that suppression. In all regions, men generally lag behind women in the expression of engagement with respect to the right to protest and reactions to the suppression of protest. Probably the most notable findings in these studies concern the role of participation in protest, which appears to strengthen engagement in agreement with the human and legal right to carry out antiwar protests and in the active condemnation of efforts to suppress them.

References

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration on inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209.

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 31, 101–119.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 364–374.

Gilgun, J. F. (2004). Deductive qualitative analysis and family theory-building. In V. Bengston, P. Dillworth Anderson, K. Allen, A. Acock, & D. Klein (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theory and research (pp. 83–84). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine.

Malley-Morrison, K., Daskalopoulos, M., & You, H. S. (2006). International perspectives on governmental aggression. International Psychology Reporter, 10(1), 19–20.

McAlister, A. (2000). Moral disengagement: Measurement & modification. Journal of Peace Research, 38(1), 87–99.

McAlister, A. L., Bandura, B., & Owen, S. (2006). Moral disengagement in support for war: The impact of September 11. Journal of Clinical and Social Psychology, 25(2), 141–165.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

McAlister, A., Campbell, T. (2013). International Perspectives on Engagement and Disengagement in Support and Suppression of Antiwar Protests. In: Malley-Morrison, K., Mercurio, A., Twose, G. (eds) International Handbook of Peace and Reconciliation. Peace Psychology Book Series, vol 7. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5933-0_21

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5933-0_21

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-5932-3

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-5933-0

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)